0 About the Sources

This book is based on historical documents, chiefly Chinese. They include imperial decrees, court records, official communications, personal correspondence, diaries and eye-witness accounts. Most of them have only come to light since the death of Mao in 1976, when historians were able to resume working on the archives. Thanks to their dedicated efforts, huge numbers of files have been sorted, studied, published, some even digitalised. Earlier publications of archive materials and scholarly works have been reissued. Thus I have had the good fortune to be able to utilise a colossal documentary pool, as well as consulting the First Historical Archives of China, the main keeper of the records to do with Empress Dowager Cixi, which holds twelve million documents. The vast majority of the sources cited have never been seen or used outside the Chinese-speaking world.

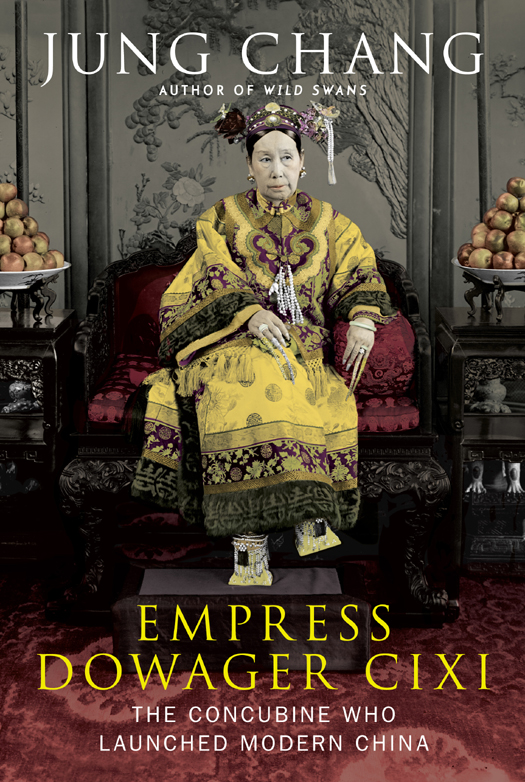

The Empress Dowager's Western contemporaries left valuable diaries, letters and memoirs. Queen Victoria's diary, Hansard and the copious international diplomatic exchanges are all rich mines of information. The Archives of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, in Washington DC, is the only place that possesses the original negatives of the photographs of Cixi.

Author's Note

The ‘tael' was the currency of China at the time. One tael weighed about 38 grams and was valued at roughly a third of a pound sterling (£1 = Tls. 3).

Chinese (and Japanese) personal names are given surname first, except for those who chose to render their names differently.

The pinyin system is used where transliteration is needed. Thus there are non-pinyin Chinese names, e.g. Canton, Tsinghua (University).

The dates and ages of people are given according to the Western system (which is used in China today). The exceptions are stated.

In the Bibliography, the publication dates are of the editions which this author consulted. Many very old books may therefore give the appearance of having been published quite recently.