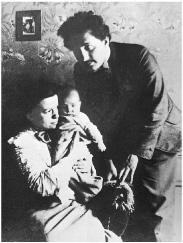

With Mileva and Hans Albert Einstein, 1904

与米列娃、汉斯·阿尔伯特在一起,1904年

Summer Vacation, 1900 1900年暑假

Newly graduated, carrying his Kirchhoff and other physics books, Einstein arrived at the end of July 1900 for his family’s summer vacation in Melchtal, a village nestled in the Swiss Alps between Lake Lucerne and the border with northern Italy. In tow was his “dreadful aunt,” Julia Koch. They were met at the train station by his mother and sister, who smothered him with kisses, and then all piled into a carriage for the ride up the mountain.

梅希塔尔(Melchtal)是一个位于瑞士卢塞恩湖和北意大利边境之间的小村庄,在阿尔卑斯山的群山掩映之下若隐若现。1900年7月底,爱因斯坦一毕业,就带着基尔霍夫等人的物理学著作前往梅希塔尔,与家人共度暑假。他那“可怕的舅妈”尤利亚·科赫与之同行。在火车站,爱因斯坦见到了妈妈和妹妹。她们的吻使他几乎透不过气来,之后大家乘马车上了山。

As they neared the hotel, Einstein and his sister got off to walk. Maja confided that she had not dared to discuss with their mother his relationship with Mileva Mari , known in the family as “the Dollie affair” after his nickname for her, and she asked him to “go easy on Mama.” It was not in Einstein’s nature, however, “to keep my big mouth shut,” as he later put it in his letter to Mari

, known in the family as “the Dollie affair” after his nickname for her, and she asked him to “go easy on Mama.” It was not in Einstein’s nature, however, “to keep my big mouth shut,” as he later put it in his letter to Mari about the scene, nor was it in his nature to protect Mari

about the scene, nor was it in his nature to protect Mari ’s feelings by sparing her all the dramatic details about what ensued.1

’s feelings by sparing her all the dramatic details about what ensued.1

快到旅馆的时候,爱因斯坦和妹妹下车步行。玛雅悄悄对他说,自己不敢和妈妈谈论他与米列娃的关系。由于他称米列娃为“多莉”,所以家里称这件事为“多莉绯闻”。玛雅希望他能够“体谅妈妈”。然而,正如爱因斯坦后来给米列娃的信中所说,“要封上我的大嘴”不合乎他的天性,同样,他也不会为了让米列娃高兴而不向她透露一切戏剧性的细节。

He went to his mother’s room and, after hearing about his exams, she asked him, “So, what will become of your Dollie now?”

爱因斯坦走进了妈妈的房间。保莉妮先是了解了他的考试情况,然后问他:“你的多莉现在情况怎样?”

“My wife,” Einstein answered, trying to affect the same nonchalance that his mother had used in her question.

“是我的妻子。”爱因斯坦回答说,言语中带着妈妈问话时的那种冷漠。

His mother, Einstein recalled, “threw herself on the bed, buried her head in the pillow, and wept like a child.” She was finally able to regain her composure and proceeded to go on the attack. “You are ruining your future and destroying your opportunities,” she said. “No decent family will have her. If she gets pregnant you’ll really be in a mess.”

爱因斯坦后来回忆说,妈妈随后“一头扑倒在床上,将头埋到枕头里,如孩子一般抽泣起来”。平静了一些之后,她又继续同他理论。“你这是在自毁前程,”她说,“任何体面的家庭都不会答应要她。如果她怀孕了,你可就麻烦大了。”

At that point, it was Einstein’s turn to lose his composure. “I vehemently denied we had been living in sin,” he reported to Mari , “and scolded her roundly.”

, “and scolded her roundly.”

这时,轮到爱因斯坦丧失理智了。“我绝不承认我们一直在非法同居,”他对米列娃说,“我狠狠地顶撞了她。”

Just as he was about to storm out, a friend of his mother’s came in, “a small, vivacious lady, an old hen of the most pleasant variety.” They promptly segued into the requisite small talk: about the weather, the new guests at the spa, the ill-mannered children. Then they went off to eat and play music.

正当他要怒气冲冲地离开时,妈妈的一个朋友走了进来。“这位太太身材娇小,活泼而有生气,是一个体态轻盈的老妇人。”她们随即寒暄起来,谈论天气,谈论最近来疗养的客人,调皮捣蛋的孩子,等等,然后一同去吃饭和演奏音乐。

Such periods of storm and calm alternated throughout the vacation. Every now and then, just when Einstein thought that the crisis had receded, his mother would revisit the topic.“Like you, she’s a book, but you ought to have a wife,” she scolded at one point. Another time she brought up the fact that Mari was 24 and he was then only 21. “By the time you’re 30, she’ll be an old witch.”

was 24 and he was then only 21. “By the time you’re 30, she’ll be an old witch.”

在整个假期当中,他们时而激烈争吵,时而相安无事。有时,爱因斯坦以为危机已经过去了,而妈妈却会重提旧事。“她像你一样是个书呆子,而你却应当有个妻子。”妈妈斥责说。还有一次,她提醒说,米列娃已经24岁,而他才21岁,“等你到30岁的时候,她就是一个老妖精了”。

Einstein’s father, still working back in Milan, weighed in with “a moralistic letter.” The thrust of his parents’ views—at least when applied to the situation of Mileva Mari rather than Marie Winteler—was that a wife was “a luxury” affordable only when a man was making a comfortable living. “I have a low opinion of that view of a relationship between a man and wife,” he told Mari

rather than Marie Winteler—was that a wife was “a luxury” affordable only when a man was making a comfortable living. “I have a low opinion of that view of a relationship between a man and wife,” he told Mari ,“because it makes the wife and the prostitute distinguishable only insofar as the former is able to secure a lifelong contract.”2

,“because it makes the wife and the prostitute distinguishable only insofar as the former is able to secure a lifelong contract.”2

爱因斯坦的爸爸当时还在米兰工作,他写了“一封说教的信”。父母的意见主要是说(至少是针对米列娃而不是玛丽),妻子是“一种奢侈品”,一个男人只有在生活宽裕之后才能担负得起。“我却瞧不起这样一种对夫妻关系的看法,”他对米列娃说,“因为照这样看来,妻子和妓女的区别仅仅在于,前者能够弄到一张终身契约。”

Over the ensuing months, there would be times when it seemed as if his parents had decided to accept their relationship. “Mama is slowly resigning herself,” Einstein wrote Mari in August. Likewise in September: “They seem to have reconciled themselves to the inevitable. I think they will both come to like you very much once they get to know you.” And once again in October: “My parents have retreated, grudgingly and with hesitation, from the battle of Dollie—now that they have seen that they’ll lose it.”3

in August. Likewise in September: “They seem to have reconciled themselves to the inevitable. I think they will both come to like you very much once they get to know you.” And once again in October: “My parents have retreated, grudgingly and with hesitation, from the battle of Dollie—now that they have seen that they’ll lose it.”3

在随后的几个月里,他的父母有时似乎已经决定接受他们的这种关系了。爱因斯坦8月给米列娃写信说:“妈妈已经差不多同我讲和了。”在9月又说:“他们似乎已经顺应了这个无可挽回的事实。两位老人一旦了解你,还是会非常喜欢你的。”在10月也说:“我的父母已经看出胜利无望,尽管犹豫不决和心怀不满,他们还是从这场围绕着多莉的斗争中退出来了。”

But repeatedly, after each period of acceptance, their resistance would flare up anew, randomly leaping into a higher state of frenzy. “Mama often cries bitterly and I don’t have a single moment of peace,” he wrote at the end of August. “My parents weep for me almost as if I had died. Again and again they complain that I have brought misfortune upon myself by my devotion to you. They think you are not healthy.”4

然而,每当他们接受这个事实之后,抵触情绪又会重新爆发,有时甚至会变成更强烈的反对。“妈妈常常伤心落泪,我简直没有片刻安宁,”他在8月底写道,“我的父母几乎为我痛哭,好像我已经死了。他们总是一再抱怨,爱你已使我惹祸上身。他们认为你身体不够健康。”

His parents’ dismay had little to do with the fact that Mari was not Jewish, for neither was Marie Winteler, nor that she was Serbian, although that certainly didn’t help her cause. Primarily, it seems, they considered her an unsuitable wife for many of the reasons that some of Einstein’s friends did: she was older, somewhat sickly, had a limp, was plain looking, and was an intense but not a star intellectual.

was not Jewish, for neither was Marie Winteler, nor that she was Serbian, although that certainly didn’t help her cause. Primarily, it seems, they considered her an unsuitable wife for many of the reasons that some of Einstein’s friends did: she was older, somewhat sickly, had a limp, was plain looking, and was an intense but not a star intellectual.

父母的沮丧与米列娃不是犹太人无关,因为玛丽也并非犹太人;与她是塞尔维亚人也没有干系,虽然这一点肯定对她无益。从根本上说,他们认为米列娃不适合做儿媳的理由似乎与爱因斯坦一些朋友的看法差不太多:她年龄较大,相貌平平,身体不够健康而且跛行,虽然充满热忱,但还不够优秀等。

All of this emotional pressure stoked Einstein’s rebellious instincts and his passion for his “wild street urchin,” as he called her. “Only now do I see how madly in love with you I am!”The relationship, as expressed in their letters, remained equal parts intellectual and emotional, but the emotional part was now filled with a fire unexpected from a self-proclaimed loner. “I just realized that I haven’t been able to kiss you for an entire month, and I long for you so terribly much,” he wrote at one point.

所有这些情感压力都激发着他那叛逆的天性以及对他的“街头小淘气”的爱恋。“直到现在我才看出我爱你有多么疯狂!”正如他们在信中所表达的,这种关系仍然是理智与情感并存,但是现在,其中的情感成分比以往更为热烈。这位将头埋入科学的沙中以躲避纯个人事情的孤独者,不经意间为这份感情加入了更多的燃料。“我刚刚意识到已经整整一个月未能吻你了,我非常非常想你。”他有一次这样写道。

During a quick trip to Zurich in August to check on his job prospects, he found himself walking around in a daze. “Without you, I lack self-confidence, pleasure in my work, pleasure in life—in short, without you my life is not life.” He even tried his hand at a poem for her, which began: “Oh my! That Johnnie boy! / So crazy with desire / While thinking of his Dollie / His pillow catches fire.”5

8月中旬,爱因斯坦曾短期去苏黎世探查他的工作前景,当时他发觉自己一片茫然,生活毫无头绪。“没有你,我就缺乏自信,工作没有兴致,生活没有欢乐——总之,没有你,我的生活就不称其为生活。”他甚至试着为她做了一首小诗,诗的开头是这样的:“哎呦呦!那个小男孩乔尼!/欲望使他完全癫狂/每当想念他的多莉/就紧攥着枕头不放。”

Their passion, however, was an elevated one, at least in their minds. With the lonely elitism of young German coffeehouse denizens who have read the philosophy of Schopenhauer once too often, they un-abashedly articulated the mystical distinction between their own rarefied spirits and the baser instincts and urges of the masses. “In the case of my parents, as with most people, the senses exercise a direct control over the emotions,” he wrote her amid the family wars of August. “With us, thanks to the fortunate circumstances in which we live, the enjoyment of life is vastly broadened.”

然而,这种激情是高贵的,至少在他们心中是如此。他们将彼此的吸引看成一种源自灵魂而非感官的力量。就像那些整日浸淫在叔本华哲学、光顾咖啡馆的德国年轻人一样,他们也持一种孤傲的精英优越论,并且毫无顾忌地渲染着自己的纯洁精神与大众低级的本能欲望之间的神秘区别。“和大多数人一样,我父母的情绪也直接受感官支配,”8月,他在家庭矛盾日益突出之时给她写信说,“而我们,由于生活在幸运的环境中,生活的乐趣也大大增加了。”

To his credit, Einstein reminded Mari (and himself) that “we mustn’t forget that many existences like my parents’ make our existence possible.” The simple and honest instincts of people like his parents had ensured the progress of civilization. “Thus I am trying to protect my parents without compromising anything that is important to me—and that means you, sweetheart!”

(and himself) that “we mustn’t forget that many existences like my parents’ make our existence possible.” The simple and honest instincts of people like his parents had ensured the progress of civilization. “Thus I am trying to protect my parents without compromising anything that is important to me—and that means you, sweetheart!”

值得称赞的是,爱因斯坦告诫米列娃(以及他自己):“我们切不可忘记,正是由于许多像我父母这样的人存在,我们才有可能存在。”他们简单而诚实的本能确保了文明的演进。“因此我正在试图体谅我的父母,同时又不放弃任何我所看重的东西——那就是你,我的宝贝!”

In his attempt to please his mother, Einstein became a charming son at their grand hotel in Melchtal. He found the endless meals excessive and the “overdressed” patrons to be “indolent and pampered,” but he dutifully played his violin for his mother’s friends, made polite conversation, and feigned a cheerful mood. It worked. “My popularity among the guests here and my music successes act as a balm on my mother’s heart.”6

就这样,爱因斯坦力争一方面顺从母亲的心意,另一方面又不背叛米列娃。在此过程中,他渐渐成为梅希塔尔大饭店人见人爱的小伙子。他虽然感觉无数珍馐美味过于奢侈,各位“衣冠楚楚的”顾客“好逸恶劳,不知餍足”,但他还是恪尽职守地为妈妈的朋友们演奏小提琴,并且假扮笑脸,毕恭毕敬地与人寒暄交谈。这一招着实奏效。“我在这些客人中颇受好评,加之我的‘音乐成就’,这些都像香膏一样敷在妈妈心上。”

As for his father, Einstein decided that the best way to assuage him, as well as to draw off some of the emotional charge generated by his relationship with Mari , was to visit him back in Milan, tour some of his new power plants, and learn about the family firm “so I can take Papa’s place in an emergency.” Hermann Einstein seemed so pleased that he promised to take his son to Venice after the inspection tour. “I’m leaving for Italy on Saturday to partake of the ‘holy sacraments’ administered by my father, but the valiant Swabian* is not afraid.”

, was to visit him back in Milan, tour some of his new power plants, and learn about the family firm “so I can take Papa’s place in an emergency.” Hermann Einstein seemed so pleased that he promised to take his son to Venice after the inspection tour. “I’m leaving for Italy on Saturday to partake of the ‘holy sacraments’ administered by my father, but the valiant Swabian* is not afraid.”

至于父亲,爱因斯坦认为要使他宽慰,或者让他收回关于自己与米列娃关系的一些情绪化指责,最好的办法就是到米兰去看他,参观他新的动力设备,熟悉一下家里开办的公司,“以便紧急情况下可以接替爸爸的位置,。赫尔曼·爱因斯坦想必很高兴,他承诺在参观完毕后带儿子去威尼斯。“星期六我启程去意大利,以享用爸爸提供的‘圣餐’,不过勇敢的施瓦本人可不害怕。”

Einstein’s visit with his father went well, for the most part. A distant yet dutiful son, he had fretted mightily about each family financial crisis, perhaps even more than his father did. But business was good for the moment, and that lifted Hermann Einstein’s spirits. “My father is a completely different man now that he has no more financial worries,” Einstein wrote Mari . Only once did the “Dollie affair” intrude enough to make him consider cutting short his visit, but this threat so alarmed his father that Einstein stuck to the original plans. He seemed flattered that his father appreciated both his company and his willingness to pay attention to the family business.7

. Only once did the “Dollie affair” intrude enough to make him consider cutting short his visit, but this threat so alarmed his father that Einstein stuck to the original plans. He seemed flattered that his father appreciated both his company and his willingness to pay attention to the family business.7

总的说来,爱因斯坦对父亲的拜望进行得不错。虽然关系有些疏远,但他毕竟是一个尽职尽责的儿子,他为每一笔家庭债务忧心忡忡,其操心程度甚至比父亲有过之而无不及。不过家里的生意当时还算不错,这使赫尔曼的精神振作了许多。“自从不必为钱发愁以来,我爸爸简直变了一个人。”爱因斯坦在信中对米列娃说。只有一次,他因“多莉绯闻”而想缩短访问行程,不过这一威胁让父亲吓坏了,爱因斯坦最终仍然按原计划行事。父亲不仅感谢他的陪伴,而且赞赏他愿意关注家里的生意,这似乎使爱因斯坦有些受宠若惊。

Even though Einstein occasionally denigrated the idea of being an engineer, it was possible that he could have followed that course at the end of the summer of 1900—especially if, on their trip to Venice, his father had asked him to, or if fate intervened so that he was needed to take his father’s place. He was, after all, a low-ranked graduate of a teaching college without a teaching job, without any research accomplishments, and certainly without academic patrons.

虽然爱因斯坦曾经诋毁过当工程师的想法,但在1900年夏末,要是在威尼斯的旅行中父亲要求他这样做,或者命运安排他接替父亲的位置,他很可能会走上这条道路。毕竟,他还是师范学院的一名没有找到教职的普通毕业生,没有任何研究成果,当然也没有研究资助。

Had he made such a choice in 1900, Einstein would have likely become a good enough engineer, but probably not a great one. Over the ensuing years he would dabble with inventions as a hobby and come up with some good concepts for devices ranging from noiseless refrigerators to a machine that measured very low voltage electricity. But none resulted in a significant engineering breakthrough or marketplace success. Though he would have been a more brilliant engineer than his father or uncle, it is not clear that he would have been any more financially successful.

倘若爱因斯坦在1900年做了这个决定,他很可能会成为一名足够好的工程师,但却称不上伟大。在随后几年中,他偶尔也会做出些发明,在闲暇之余实践一些工程想法,想出一些不错的主意应用在各种设备上,比如无噪声冰箱,或者测量极低电压的机器,但这些发明中没有一项能促成重要的工程突破,也没有一种能在市场上取得巨大成功。尽管他做工程可能比父亲或舅舅更出色,但在赚钱方面却未必能更成功。

Among the many surprising things about the life of Albert Einstein was the trouble he had getting an academic job. Indeed, it would be an astonishing nine years after his graduation from the Zurich Polytechnic in 1900—and four years after the miracle year in which he not only upended physics but also finally got a doctoral dissertation accepted—before he would be offered a job as a junior professor.

爱因斯坦一生中发生过众多离奇的事件,其中之一便是难于获得一个教职。事实上,直到1900年他从苏黎世联邦工学院毕业之后九年(以及在促成物理学革命并最终获得博士学位的奇迹年之后四年),他才被授予了一个初级教授职位。

The delay was not due to a lack of desire on his part. In the middle of August 1900, between his family vacation in Melchtal and his visit to his father in Milan, Einstein stopped back in Zurich to see about getting a post as an assistant to a professor at the Polytechnic. It was typical that each graduate would find, if he wanted, some such role, and Einstein was confident it would happen. In the meantime, he rejected a friend’s offer to help him get a job at an insurance company, dismissing it as “an eight hour day of mindless drudgery.” As he told Mari , “One must avoid stultifying affairs.”8

, “One must avoid stultifying affairs.”8

事实上,这种耽搁并非他本人所愿。1900年8月中旬,在同家人在梅希塔尔度假以及到米兰拜望父亲期间,爱因斯坦在苏黎世待了一段时间,他想为联邦工学院的某位教授做助手。一般来说,只要本人愿意,每位毕业生都可以找到某个这样的职位,爱因斯坦也相信自己能够做到。与此同时,他谢绝了一位朋友帮他找到的在一家保险公司任职的机会,并斥之为“像傻瓜那样每天做8小时苦工”。正如他对米列娃所说:“对于这些使人愚昧的事情,人必须退避三舍。”

The problem was that the two physics professors at the Polytechnic were acutely aware of his impudence but not of his genius. Getting a job with Professor Pernet, who had reprimanded him, was not even a consideration. As for Professor Weber, he had developed such an allergy to Einstein that, when no other graduates of the physics and math department were available to become his assistant, he instead hired two students from the engineering division.

但问题在于,联邦工学院的两位物理学教授非常清楚爱因斯坦的无礼,却不知道他的天才。对于在申斥过自己的佩尔内教授那里找一份工作,爱因斯坦想都没想过。至于韦伯教授,他对爱因斯坦已经十分反感,以至于当他找不到物理系和数学系的毕业生做助手时,竟然从工程系雇了两个学生。

That left math professor Adolf Hurwitz. When one of Hurwitz’s assistants got a job teaching at a high school, Einstein exulted to Mari : “This means I will become Hurwitz’s servant, God willing.” Unfortunately, he had skipped most of Hurwitz’s classes, a slight that apparently had not been forgotten.9

: “This means I will become Hurwitz’s servant, God willing.” Unfortunately, he had skipped most of Hurwitz’s classes, a slight that apparently had not been forgotten.9

于是只剩下数学教授阿道夫·胡尔维茨了。当爱因斯坦听说,胡尔维茨的一位助手找到了一份在中学教书的工作时,他高兴地对米列娃说:“这说明根据神的旨意,我将成为胡尔维茨的奴仆。”但不幸的是,他曾经逃过胡尔维茨的大多数课程,这种轻视和怠慢显然并没有被忘却。

By late September, Einstein was still staying with his parents in Milan and had not received an offer. “I plan on going to Zurich on October 1 to talk with Hurwitz personally about the position,” he said. “It’s certainly better than writing.”

到了9月底,爱因斯坦仍然与父母待在米兰,没有找到一个职位。“我打算10月1日去苏黎世,亲自与胡尔维茨谈职务问题,”他说,“这样做毕竟比写信要好。”

While there, he also planned to look for possible tutoring jobs that could tide them over while Mari prepared to retake her final exams. “No matter what happens, we’ll have the most wonderful life in the world. Pleasant work and being together—and what’s more, we now answer to no one, can stand on our own two feet, and enjoy our youth to the utmost. Who could have it any better? When we have scraped together enough money, we can buy bicycles and take a bike tour every couple of weeks.”10

prepared to retake her final exams. “No matter what happens, we’ll have the most wonderful life in the world. Pleasant work and being together—and what’s more, we now answer to no one, can stand on our own two feet, and enjoy our youth to the utmost. Who could have it any better? When we have scraped together enough money, we can buy bicycles and take a bike tour every couple of weeks.”10

他也计划在那里找几份家教,从而在米列娃备考期间使他们共渡难关。“不论发生什么,我们都将拥有这个世界上最美妙的生活。合意的工作并且在一起——不仅如此,我们现在不依赖任何人,完全能够独立自主地生活,尽情享受我们的青春。谁还有比这更好的生活呢?等我们攒够钱之后就买自行车,每隔几周就骑车郊游一次。”

Einstein ended up deciding to write Hurwitz instead of visiting him, which was probably a mistake. His two letters do not stand as models for future generations seeking to learn how to write a job application. He readily conceded that he did not show up at Hurwitz’s calculus classes and was more interested in physics than math. “Since lack of time prevented me from taking part in the mathematics seminar,” he rather lamely said, “there is nothing in my favor except the fact that I attended most of the lectures offered.” Rather presumptuously, he said he was eager for an answer because “the granting of citizenship in Zurich, for which I have applied, has been made conditional upon my proving that I have a permanent job.”11

爱因斯坦最终还是决定给胡尔维茨写信而不是登门拜访,这也许是个失误。但愿他的两封信不会成为职务申请书的范本。他坦言自己并没有去听胡尔维茨的微积分课,因为较之数学,他对物理学更有兴趣。“由于时间不够,我未能参加数学专题研讨班,”他提出了这种蹩脚的借口,“这些课程我都不感兴趣,但我确实上过大部分课程。”他还放肆地说自己希望能有一个答复,因为“授予我所申请的苏黎世公民权,需要一份固定职位证明”。

Einstein’s impatience was matched by his confidence. “Hurwitz still hasn’t written me more,” he said only three days after sending his letter, “but I have hardly any doubt that I will get the position.” He did not. Indeed, he managed to become the only person graduating in his section of the Polytechnic who was not offered a job. “I was suddenly abandoned by everyone,” he later recalled.12

与爱因斯坦的急躁相映成趣的是他的自信。“胡尔维茨还没有给我回信,”发出信后仅三天,他就说出了这番话,“不过我几乎毫不怀疑自己能够得到这个职位。”然而他终究没有得到。事实上,在从他所在的系里毕业的所有联邦工学院学生当中,他是唯一一个没有找到工作的人。“忽然之间我被所有人抛弃了。”他后来回忆说。

By the end of October 1900 he and Mari were both back in Zurich, where he spent most of his days hanging out at her apartment, reading and writing. On his citizenship application that month, he wrote “none” on the question asking his religion, and for his occupation he wrote, “I am giving private lessons in mathematics until I get a permanent position.”

were both back in Zurich, where he spent most of his days hanging out at her apartment, reading and writing. On his citizenship application that month, he wrote “none” on the question asking his religion, and for his occupation he wrote, “I am giving private lessons in mathematics until I get a permanent position.”

到了1900年10月底,他和米列娃都回到了苏黎世。在那里,他大部分时间都待在公寓里读书和写作。在当月的公民身份申请表中,他在有关宗教背景的一栏中写了“无”。关于职业他写道:“我正在做数学家教,直到获得固定职位为止。”

Throughout that fall, he was able to find only eight sporadic tutoring jobs, and his relatives had ended their financial support. But Einstein put up an optimistic front. “We support ourselves by private lessons, if we can ever pick up some, which is still very doubtful,” he wrote a friend of Mari ’s. “Isn’t this a journeyman’s or even a gypsy’s life? But I believe that we will remain cheerful in it as ever.”13 What kept him happy, in addition to Mari

’s. “Isn’t this a journeyman’s or even a gypsy’s life? But I believe that we will remain cheerful in it as ever.”13 What kept him happy, in addition to Mari ’s presence, were the theoretical papers he was writing on his own.

’s presence, were the theoretical papers he was writing on his own.

那年秋天,爱因斯坦只零零星星找到了八份家教。他的亲戚已经终止了对他的经济资助,但他仍强作笑脸。“我们靠着给人补习功课来维持生活,只要随便碰上几个人就可以了,可是这件事仍然很成问题,”他写信给米列娃的一个朋友说,“这岂不是一个短工,甚或就是一个吉卜赛人的生活吗?不过我相信,即使在这种情况下,我们也会像往常一样快活。”除了有米列娃做伴,使他保持乐观情绪的还有那些他正在独立写作的论文。

Einstein’s First Published Paper 爱因斯坦发表的第一篇论文

The first of these papers was on a topic familiar to most school kids: the capillary effect that, among other things, causes water to cling to the side of a straw and curve upward. Although he later called this essay “worthless,” it is interesting from a biographical perspective. Not only is it Einstein’s first published paper, but it shows him heartily embracing an important premise—one not yet fully accepted—that would be at the core of much of his work over the next five years: that molecules (and their constituent atoms) actually exist, and that many natural phenomena can be explained by analyzing how these particles interact with one another.

第一篇论文的主题是许多学生都熟悉的毛细现象,比如水可以沿着稻草一侧顺流而上。虽然他后来称这篇论文“没有价值”,但从传记的角度来看,它还是很有意思的。不仅因为这是爱因斯坦发表的第一篇论文,而且也因为它表明爱因斯坦完全赞同当时还没有被广泛接受的一个重要假说,即分子(以及构成它们的原子)实际存在着,许多自然现象都可以通过分析这些粒子如何相互作用而得到解释。在接下来的五年中,这一预设将在他的工作中发挥核心作用。

During his vacation in the summer of 1900, Einstein had been reading the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, who had developed a theory of gases based on the behavior of countless molecules bouncing around. “The Boltzmann is absolutely magnificent,” he enthused to Mari in September. “I am firmly convinced of the correctness of the principles of his theory, i.e., I am convinced that in the case of gases we are really dealing with discrete particles of definite finite size which move according to certain conditions.”14

in September. “I am firmly convinced of the correctness of the principles of his theory, i.e., I am convinced that in the case of gases we are really dealing with discrete particles of definite finite size which move according to certain conditions.”14

1900年暑假期间,爱因斯坦一直在研读玻尔兹曼的著作,后者曾经基于无数来回弹跳的分子的活动提出了一种气体理论。“这位玻尔兹曼是个出色的阐述者,”9月里,他激动地对米列娃说,“我坚信他的理论原理是正确的,也就是说,我确信对于气体,我们实际上要处理的是一些具有确定尺寸的分离的粒子,它们依照特定的条件运动着。”

To understand capillarity, however, required looking at the forces acting between molecules in a liquid, not a gas. Such molecules attract one another, which accounts for the surface tension of a liquid, or the fact that drops hold together, as well as for the capillary effect. Einstein’s idea was that these forces might be analogous to Newton’s gravitational forces, in which two objects are attracted to each other in proportion to their mass and in inverse proportion to their distance from one another.

然而,要理解毛细现象,需要考察的是液体分子而不是气体分子之间的作用力。这些分子相互吸引,从而产生了液体的表面张力(它使液滴能够聚在一起)和毛细现象。爱因斯坦认为,这些力也许类似于牛顿的引力。根据牛顿的理论,任何两个物体都会相互吸引,引力大小与它们的质量成正比,与两者距离的平方成反比。

Einstein looked at whether the capillary effect showed such a relationship to the atomic weight of various liquid substances. He was encouraged, so he decided to see if he could find some experimental data to test the theory further. “The results on capillarity I recently obtained in Zurich seem to be entirely new despite their simplicity,” he wrote Mari . “When we’re back in Zurich we’ll try to get some empirical data on this subject . . . If this yields a law of nature, we’ll send the results to the Annalen.”15

. “When we’re back in Zurich we’ll try to get some empirical data on this subject . . . If this yields a law of nature, we’ll send the results to the Annalen.”15

爱因斯坦试图考察毛细现象是否也与液体的原子量有这样一种关系。这个想法得到了鼓励,他决定看看是否可以找到一些实验数据来进一步验证这一理论。“我最近在苏黎世得到的那些有关毛细现象的结果,尽管看上去简单,却是全新的,”他写信给米列娃说,“我们到苏黎世之后,要争取弄到一些这方面的经验数据……如果得出一条自然定律,我们就把它寄给《物理学纪事》。”

He did end up sending the paper in December 1900 to the Annalen der Physik, Europe’s leading physics journal, which published it the following March. Written without the elegance or verve of his later papers, it conveyed what is at best a tenuous conclusion. “I started from the simple idea of attractive forces among the molecules, and I tested the consequences experimentally,” he wrote. “I took gravitational forces as an analogy.” At the end of the paper, he declares limply, “The question of whether and how our forces are related to gravitational forces must therefore be left completely open for the time being.”16

《物理学纪事》(Annalen der Physik)是欧洲顶尖的物理学杂志。1900年12月,他终于将论文寄给了这个杂志,并于次年3月发表。这篇论文不像他后来的论文那样精确简练,而是给出了一个比较含糊的结论。“我从分子间的吸引这一简单观念出发,用实验检验了它的推论,”他写道,“我将它与引力做类比。,在论文的结尾,他无可奈何地宣布,“关于我们的力是否以及如何与引力相关联,暂时还不能得到令人满意的结论。”

The paper elicited no comments and contributed nothing to the history of physics. Its basic conjecture was wrong, as the distance dependence is not the same for differing pairs of molecules.17 But it did get him published for the first time. That meant that he now had a printed article to attach to the job-seeking letters with which he was beginning to spam professors all over Europe.

这篇论文没有受到后人关注,在物理学史上没有留下什么影响。其基本猜想是错误的,因为不同的分子对距离的依赖关系是不同的。但这毕竟是爱因斯坦第一次发表文章。这意味着他可以在求职信中附上一篇发表的论文,并向全欧洲的教授做广告。

In his letter to Mari , Einstein had used the term “we” when discussing plans to publish the paper. In two letters written the month after it appeared, Einstein referred to “our theory of molecular forces” and “our investigation.”Thus was launched a historical debate over how much credit Mari

, Einstein had used the term “we” when discussing plans to publish the paper. In two letters written the month after it appeared, Einstein referred to “our theory of molecular forces” and “our investigation.”Thus was launched a historical debate over how much credit Mari deserves for helping Einstein devise his theories.

deserves for helping Einstein devise his theories.

在给米列娃的信中,爱因斯坦在讨论计划发表论文时用了“我们”一词。在论文发表后的那个月写的两封信中,爱因斯坦提到了“我们的分子力理论,以及“我们的研究”。这便掀起了一场历史争论,即米列娃在多大程度上帮助爱因斯坦提出了自己的理论。

In this case, she mainly seemed to be involved in looking up some data for him to use. His letters conveyed his latest thoughts on molecular forces, but hers contained no substantive science. And in a letter to her best friend, Mari sounded as if she had settled into the role of supportive lover rather than scientific partner. “Albert has written a paper in physics that will probably be published very soon in the Annalen der Physik,” she wrote. “You can imagine how very proud I am of my darling. This is not just an everyday paper, but a very significant one. It deals with the theory of liquids.”18

sounded as if she had settled into the role of supportive lover rather than scientific partner. “Albert has written a paper in physics that will probably be published very soon in the Annalen der Physik,” she wrote. “You can imagine how very proud I am of my darling. This is not just an everyday paper, but a very significant one. It deals with the theory of liquids.”18

就这个问题而言,她似乎主要是帮助查阅了一些资料供他使用。爱因斯坦的信传递出他关于分子力的一些最新思想,而米列娃的信却不包含实质性的科学内容。在给自己最好的朋友的信中,米列娃的说法听起来就好像她一直充当着恋人的支持者,而不是科学上的伙伴。“阿尔伯特已经写出了一篇物理论文,也许最近就会在《物理学纪事》上发表,”她写道,“你可以想象,我为我的爱人感到多么自豪。你知道,这可不是普普通通的论文,而是很重要的,内容涉及流体理论。”

Jobless Anguish 失业的痛苦

It had been almost four years since Einstein had renounced his German citizenship, and ever since then he had been stateless. Each month, he put aside some money toward the fee he would need to pay to become a Swiss citizen, a status he deeply desired. One reason was that he admired the Swiss system, its democracy, and its gentle respect for individuals and their privacy. “I like the Swiss because, by and large, they are more humane than the other people among whom I have lived,” he later said.19 There were also practical reasons; in order to work as a civil servant or a teacher in a state school, he would have to be a Swiss citizen.

自从爱因斯坦放弃德国国籍,时间不知不觉已经过去了四年。从那时起,他就一直是一个没有国籍的人。他渴望自己有一天能够加入瑞士国籍,为此他每个月都会留出一些钱,以便日后及时缴纳入籍费用。因为他欣赏瑞士的社会制度和民主,欣赏那里对个人和隐私的尊重。“我之所以喜欢瑞士人,是因为一般来说,他们要比我平日里接触的那些人更有人情味。”他后来说。此外,他还有一些实际的考虑。要做公务员,或者在州立学校当老师,他必须先成为瑞士公民。

The Zurich authorities examined him rather thoroughly, and they even sent to Milan for a report on his parents. By February 1901, they were satisfied, and he was made a citizen. He would retain that designation his entire life, even as he accepted citizenships in Germany (again), Austria, and the United States. Indeed, he was so eager to be a Swiss citizen that he put aside his antimilitary sentiments and presented himself, as required, for military service. He was rejected for having sweaty feet (“hyperidrosis ped”), flat feet (“pes planus”), and varicose veins (“varicosis”). The Swiss Army was, apparently, quite discriminating, and so his military service book was stamped “unfit.”20

苏黎世当局对他的情况做了非常彻底的调查,甚至差人到来兰去取关于他父母的一份报告。1901年2月,他们终于同意了这份申请,爱因斯坦成为瑞士公民。他将终生保留瑞士国籍,即使在他后来又(重新)接受了德国、奥地利和美国国籍之后也是如此。事实上,他为了成为瑞士公民,甚至将自己的反战情绪暂时抛开,按照要求申请服兵役。不过由于汗脚、平足和静脉曲张,他被拒绝了。瑞士军队显然非常有鉴别力,他的兵役手册上盖的章为一“不合格”。

A few weeks after he got his citizenship, however, his parents insisted that he come back to Milan and live with them. They had decreed, at the end of 1900, that he could not stay in Zurich past Easter unless he got a job there. When Easter came, he was still unemployed.

可就在爱因斯坦获得瑞士国籍之后几周,父母要他快点回米兰同他们住在一起。1900年年底,他们希望他在复活节前离开苏黎世,除非他在那里找到工作。然而到了复活节,他仍处于失业的痛苦之中。

Mari , not unreasonably, assumed that his summons to Milan was due to his parents’ antipathy toward her. “What utterly depressed me was the fact that our separation had to come about in such an unnatural way, on account of slanders and intrigues,” she wrote her friend. With an absentmindedness he was later to make iconic, Einstein left behind in Zurich his nightshirt, toothbrush, comb, hairbrush (back then he used one), and other toiletries. “Send everything along to my sister,” he instructed Mari

, not unreasonably, assumed that his summons to Milan was due to his parents’ antipathy toward her. “What utterly depressed me was the fact that our separation had to come about in such an unnatural way, on account of slanders and intrigues,” she wrote her friend. With an absentmindedness he was later to make iconic, Einstein left behind in Zurich his nightshirt, toothbrush, comb, hairbrush (back then he used one), and other toiletries. “Send everything along to my sister,” he instructed Mari , “so she can bring them home with her.” Four days later, he added, “Hold on to my umbrella for the time being. We’ll figure out something to do with it later.”21

, “so she can bring them home with her.” Four days later, he added, “Hold on to my umbrella for the time being. We’ll figure out something to do with it later.”21

米列娃自然会认为,爱因斯坦被召回米兰缘于他的父母对自己的反感。“最令我懊丧的却是由于污蔑诽谤、阴谋诡计而使我们不得不硬生生地分开。”她在给一位朋友的信中说。他以其一贯的心不在焉,把睡衣、牙刷、梳子、发刷等洗漱用品都留在了苏黎世。“把所有这些东西都送到我妹妹那里,”他嘱咐米列娃,“她可以把它们带回来。”四天后他又说:“暂且将我的雨伞保存起来。以后能派上用场。”

Both in Zurich and then in Milan, Einstein churned out job-seeking letters, ever more pleading, to professors around Europe. They were accompanied by his paper on the capillary effect, which proved not particularly impressive; he rarely even received the courtesy of a response. “I will soon have graced every physicist from the North Sea to the southern tip of Italy with my offer,” he wrote Mari .22

.22

在苏黎世和米兰,爱因斯坦向全欧洲的教授发去了一封封求职信,信中同时附上那篇关于毛细现象的论文。事实证明,这篇论文并未特别奏效。这些信件大都石沉大海,爱因斯坦甚至连礼节性的回复都没怎么收到。“不用多久,我就会以我的报价给波罗的海至意大利南端的所有物理学家增光。”他写信给米列娃。

By April 1901, Einstein was reduced to buying a pile of postcards with postage-paid reply attachments in the forlorn hope that he would, at least, get an answer. In the two cases where these postcard pleas have survived, they have become, rather amusingly, prized collectors’ items. One of them, to a Dutch professor, is now on display in the Leiden Museum for the History of Science. In both cases, the return-reply attachment was not used; Einstein did not even get the courtesy of a rejection. “I leave no stone unturned and do not give up my sense of humor,” he wrote his friend Marcel Grossmann. “God created the donkey and gave him a thick skin.”23

到了1901年4月,几近绝望的爱因斯坦不得不买了一堆附有邮资已付的回执的明信片寄出去,希望至少能够得到一个回音。有趣的是,有两张留存至今的明信片已成为收藏者的珍爱之物。其中一张是寄给荷兰教授的,现藏莱顿科学史博物馆。这两张明信片的“退还一回复”的附件均没有被用过,他甚至连一次礼节性的婉拒都没有收到。“尽管如此,我还是在不遗余力地想办法,而且也不让自己失去幽默感,”他给老朋友格罗斯曼写信说,“上帝创造了蠢驴,还给了它一张厚皮呢。”

Among the great scientists Einstein wrote was Wilhelm Ostwald, professor of chemistry in Leipzig, whose contributions to the theory of dilution were to earn him a Nobel Prize. “Your work on general chemistry inspired me to write the enclosed article,” Einstein said. Then flattery turned to plaintiveness as he asked “whether you might have use for a mathematical physicist.” Einstein concluded by pleading: “I am without money, and only a position of this kind would enable me to continue my studies.” He got no answer. Einstein wrote again two weeks later using the pretext “I am not sure whether I included my address” in the earlier letter. “Your judgment of my paper matters very much to me.” There was still no answer.24

在爱因斯坦去信的大科学家中,有一位是莱比锡大学的化学教授威廉·奥斯特瓦尔德,他后来因对稀释理论的贡献而获得诺贝尔化学奖。“您在普通化学方面的著作激励我写出这篇随信附上的论文。”爱因斯坦说。在这之后,其语气由逢迎转为悲哀,他问:“是否还有可能用得上一位数学物理学者?”爱因斯坦最后恳求说:“我一贫如洗,而且也只有这样一个职位才能使我继续进行自己的研究。”这封信发出去之后如石沉大海,未获答复。两个星期后,爱因斯坦又再次写信给他,借口说“我忘了当时是否附上了我的地址”,“您对我论文的评价对我至关重要”。然而,信发出后依然杳无音讯。

Einstein’s father, with whom he was living in Milan, quietly shared his son’s anguish and tried, in a painfully sweet manner, to help. When no answer came after the second letter to Ostwald, Hermann Einstein took it upon himself, without his son’s knowledge, to make an unusual and awkward effort, suffused with heart-wrenching emotion, to prevail upon Ostwald himself:

与爱因斯坦一同住在米兰的父亲非常同情儿子的痛苦,他试图通过一种令人辛酸的讨好方式助他一臂之力。在第二封寄给奥斯特瓦尔德的信未获回音之后,赫尔曼在未告知爱因斯坦的情况下做出了一个不寻常的举动,他亲自写信劝说奥斯特瓦尔德,字里行间渗透着悲苦:

Please forgive a father who is so bold as to turn to you, esteemed Herr Professor, in the interest of his son.

请宽恕一位父亲为了他儿子的利益竟敢向您——尊敬的教授先生求助乞援。

Albert is 22 years old, he studied at the Zurich Polytechnic for four years, and he passed his exam with flying colors last summer. Since then he has been trying unsuccessfully to get a position as a teaching assistant, which would enable him to continue his education in physics. All those in a position to judge praise his talents; I can assure you that he is extraordinarily studious and diligent and clings with great love to his science.

阿尔伯特今年22岁,曾在苏黎世联邦工学院读了四年,去年夏天以优异的成绩通过了数学和物理专业的毕业考试。自那时起他就在谋求一个助教职位,使他有可能在理论物理和实验物理方面继续深造,可是这一切努力都是枉然。所有能够判断此事的人都称赞他的才能,我可以保证他非常有上进心而且勤奋好学,极其热爱他的科学。

He therefore feels profoundly unhappy about his current lack of a job, and he becomes more and more convinced that he has gone off the tracks with his career. In addition, he is oppressed by the thought that he is a burden on us, people of modest means.

我的儿子对于他目前的失业深感痛苦,认为他的职业已经渐行渐远。此外,他认为自己已经成了我们的累赘,而我们是不大富裕的人。这种想法在他心里总是盘踞不去。

Since it is you whom my son seems to admire and esteem more than any other scholar in physics, it is you to whom I have taken the liberty of turning with the humble request to read his paper and to write to him, if possible, a few words of encouragement, so that he might recover his joy in living and working.

尊敬的教授先生,正是因为在当今所有的物理学者中,我儿子最仰慕您也最敬重您,我才不揣冒昧直接向您求助,还望您能够读一下他发表在《物理学纪事》上的论文,如有可能,还请寄给他几行鼓励的话,他会因此而重获生活和工作的喜悦。

If, in addition, you could secure him an assistant’s position, my gratitude would know no bounds. I beg you to forgive me for my impudence in writing you, and my son does not know anything about my unusual step.25

此外,倘若您能为他谋求一个助教职位,我将感激不尽。 再次恳求您原谅我冒昧地给您写这样的信,我的儿子对于我这种异乎寻常的做法一无所知。

Ostwald still did not answer. However, in one of history’s nice ironies, he would become, nine years later, the first person to nominate Einstein for the Nobel Prize.

奥斯特瓦尔德依旧没有回信。不过九年之后,他第一个提名爱因斯坦获诺贝尔奖,这种历史讽刺真让人有些哭笑不得。

Einstein was convinced that his nemesis at the Zurich Polytechnic, physics professor Heinrich Weber, was behind the difficulties. Having hired two engineers rather than Einstein as his own assistant, he was apparently now giving him unfavorable references. After applying for a job with Göttingen professor Eduard Riecke, Einstein despaired to Mari : “I have more or less given up the position as lost. I cannot believe that Weber would let such a good opportunity pass without doing some mischief.” Mari

: “I have more or less given up the position as lost. I cannot believe that Weber would let such a good opportunity pass without doing some mischief.” Mari advised him to write Weber, confronting him directly, and Einstein reported back that he had. “He should at least know that he cannot do these things behind my back. I wrote to him that I know that my appointment now depends on his report alone.”

advised him to write Weber, confronting him directly, and Einstein reported back that he had. “He should at least know that he cannot do these things behind my back. I wrote to him that I know that my appointment now depends on his report alone.”

爱因斯坦确信,在这些挫折背后,有他在苏黎世联邦工学院的对手——物理学教授韦伯——在作梗。在聘用两名工程师而不是爱因斯坦做助手之后,他现在写的证明书显然会对爱因斯坦不利。在向哥廷根大学教授爱德华·里克求职未果的情况下,爱因斯坦绝望地对米列娃说:“我对这个职位几乎不再抱有希望。我不大相信韦伯会放过这样一个好机会不去干点儿什么勾当。”米列娃建议他直接给韦伯写信进行抗争,爱因斯坦说他已经这样做了。“他至少应当明白,他不可以背着我为所欲为。我在信上说,我知道我的任命现在全仗他的证明书。”

It didn’t work. Einstein again got turned down. “Riecke’s rejection hasn’t surprised me,” he wrote Mari . “I’m completely convinced that Weber is to blame.” He became so discouraged that, at least for the moment, he felt it futile to continue his search. “Under these circumstances it no longer makes sense to write further to professors, since, should things get far enough along, it is certain they would all enquire with Weber, and he would again give a poor reference.” To Grossmann he lamented, “I could have found a job long ago had it not been for Weber’s underhandedness.”26

. “I’m completely convinced that Weber is to blame.” He became so discouraged that, at least for the moment, he felt it futile to continue his search. “Under these circumstances it no longer makes sense to write further to professors, since, should things get far enough along, it is certain they would all enquire with Weber, and he would again give a poor reference.” To Grossmann he lamented, “I could have found a job long ago had it not been for Weber’s underhandedness.”26

这次求职依然没有奏效。爱因斯坦又一次被拒绝了。“里克的回绝并不使我感到意外,”他写信给米列娃,“我坚信责任在韦伯。”至少在当时,他变得极为消沉,觉得即便再这样找下去也不会有什么结果。“在这种情况下再给教授们写信是没有意义的,因为事情一旦有些眉目,他们必定会向韦伯了解情况,而韦伯肯定会给出不利于我的证明书。”他向格罗斯曼悲叹道,“要不是韦伯耍花招跟我作对,我老早就找到工作了。”

To what extent did anti-Semitism play a role? Einstein came to believe that it was a factor, which led him to seek work in Italy, where he felt it was not so pronounced. “One of the main obstacles in getting a position is absent here, namely anti-Semitism, which in German-speaking countries is as unpleasant as it is a hindrance,” he wrote Mari . She, in turn, lamented to her friend about her lover’s difficulties. “You know my sweetheart has a sharp tongue and moreover he is a Jew.”27

. She, in turn, lamented to her friend about her lover’s difficulties. “You know my sweetheart has a sharp tongue and moreover he is a Jew.”27

那么,反犹主义是否也在一定程度上起了推波助澜的作用呢?爱因斯坦渐渐认为这同样是一个因素,这促使他前往意大利去找工作,他觉得那里的排犹情绪还不明显。“获得职位的一个主要障碍——反犹主义在这里并不存在,而在讲德语的国家,它既让我感到厌恶,也对我很不利。”他写信给米列娃。她则向一位朋友谈起了爱因斯坦的苦恼:“你知道我的爱人有一张利嘴,而且他还是个犹太人。”

In his effort to find work in Italy, Einstein enlisted one of the friends he had made while studying in Zurich, an engineer named Michele Angelo Besso. Like Einstein, Besso was from a middle-class Jewish family that had wandered around Europe and eventually settled in Italy. He was six years older than Einstein, and by the time they met he had already graduated from the Polytechnic and was working for an engineering firm. He and Einstein forged a close friendship that would last for the rest of their lives (they died within weeks of each other in 1955).

当爱因斯坦正在意大利为找工作疲于奔命之时,他在苏黎世求学期间结识的一位朋友伸出了援手。他叫米歇勒·贝索,是一名工程师。和爱因斯坦一样,贝索也来自一个中产阶级犹太家庭。他们当初在整个欧洲四处流浪,最后落户于意大利。贝索比爱因斯坦大6岁,他们初次见面时,贝索刚刚从联邦工学院毕业,正在一家工程公司工作。然而,他却与爱因斯坦结成了亲密的友谊,这种友谊将会一直伴随他们走完生命的全程(1955年他们去世的时间相差不过数周)。

Over the years, Besso and Einstein would share both the most intimate personal confidences and the loftiest scientific notions. As Einstein wrote in one of the 229 extant letters they exchanged, “Nobody else is so close to me, nobody knows me so well, nobody is so kindly disposed to me as you are.”28

贝索和爱因斯坦都秉持着最崇高的科学理念,彼此互为最亲密的知心朋友,他们之间的通信现存229封。正如爱因斯坦在其中一封信中所说:“在所有人当中,你爱我最深切,也最理解我。”

Besso had a delightful intellect, but he lacked focus, drive, and diligence. Like Einstein, he had once been asked to leave high school because of his insubordinate attitude (he sent a petition complaining about a math teacher). Einstein called Besso “an awful weakling . . . who cannot rouse himself to any action in life or scientific creation, but who has an extraordinarily fine mind whose working, though disorderly, I watch with great delight.”

贝索虽然头脑聪明,但是不够专注,缺乏干劲,勤奋刻苦的程度也不足。和爱因斯坦一样,他在中学时也曾因为无礼而被勒令退学(为了发泄对一位数学老师的不满,他发出了一封请愿书)。爱因斯坦称贝索是“一个性格非常软弱的人……不能振作起来在生活和科学创造中有所作为,但聪明绝顶。他的工作虽然没有头绪,我却看得颇有兴味”。

Einstein had introduced Besso to Anna Winteler of Aarau, Marie’s sister, whom he ended up marrying. By 1901 he had moved to Trieste with her. When Einstein caught up with him, he found Besso as smart, as funny, and as maddeningly unfocused as ever. He had recently been asked by his boss to inspect a power station, and he decided to leave the night before to make sure that he arrived on time. But he missed his train, then failed to get there the next day, and finally arrived on the third day—“but to his horror realizes that he has forgotten what he’s supposed to do.” So he sent a postcard back to the office asking them to resend his instructions. It was the boss’s assessment that Besso was “completely useless and almost unbalanced.”

爱因斯坦后来把贝索介绍给了玛丽的姐姐——安娜·温特勒,他们最终成为夫妻。1901年,贝索搬到了的里雅斯特与安娜生活在一起。当爱因斯坦见到他时,发现贝索还和以前一样聪明机敏、逗人发笑和没有目标。就在那不久前,贝索的上司派他去检查一家电厂,他决定在前一天晚上动身,以确保准时赶到。然而还是误了火车,第二天没有赶到,直到第三天才赶到那里——“可是他惊恐地发现,自己已经记不起到这里是要办什么事情了”。于是他立即给单位寄去一张明信片,要他们重新告诉他应该做什么。上司对贝索的评价是“完全无用,几乎精神错乱”。

Einstein’s assessment of Besso was more loving. “Michele is an awful schlemiel,” he reported to Mari , using the Yiddish word for a hapless bumbler. One evening, Besso and Einstein spent almost four hours talking about science, including the properties of the mysterious ether and “the definition of absolute rest.”These ideas would burst into bloom four years later, in the relativity theory that he would devise with Besso as his sounding board. “He’s interested in our research,” Einstein wrote Mari

, using the Yiddish word for a hapless bumbler. One evening, Besso and Einstein spent almost four hours talking about science, including the properties of the mysterious ether and “the definition of absolute rest.”These ideas would burst into bloom four years later, in the relativity theory that he would devise with Besso as his sounding board. “He’s interested in our research,” Einstein wrote Mari , “though he often misses the big picture by worrying about petty considerations.”

, “though he often misses the big picture by worrying about petty considerations.”

爱因斯坦对贝索的评价则更加有趣。“米歇勒真是个笨手笨脚的倒霉蛋儿。”他用犹太人说的意第绪语对米列娃说。一天晚上,贝索与爱因斯坦足足谈了4小时科学,其中包括那种神秘的以太以及“对绝对静止的定义”。4年之后,这些想法将在他的狭义相对论中开花结果,贝索正是他当时征求意见的对象。“贝索对我们的研究工作很感兴趣,”爱因斯坦写信给米列娃,“尽管他常常由于纠缠于一些细枝末节而忽略了全局。”

Besso had some connections that could, Einstein hoped, be useful. His uncle was a mathematics professor at the polytechnic in Milan, and Einstein’s plan was to have Besso provide an introduction: “I’ll grab him by the collar and drag him to his uncle, where I’ll do the talking myself.” Besso was able to persuade his uncle to write letters on Einstein’s behalf, but nothing came of the effort. Instead, Einstein spent most of 1901 juggling temporary teaching assignments and some tutoring.29

爱因斯坦希望贝索能够为自己的谋职做一些牵线搭桥的工作。贝索的舅舅是米兰联邦工学院的数学教授,爱因斯坦打算让贝索引介一下。“我会揪住他的衣领把他拖到他舅舅跟前,然后我自己出面来谈”。虽然贝索说服了舅舅为爱因斯坦写信,但这一努力还是无果而终。在1901年的大部分时间里,爱因斯坦都是既承担一些临时的教学任务,同时也做一些家教。

It was Einstein’s other close friend from Zurich, his classmate and math note-taker Marcel Grossmann, who ended up finally getting Einstein a job, though not one that would have been expected. Just when Einstein was beginning to despair, Grossmann wrote that there was likely to be an opening for an examiner at the Swiss Patent Office, located in Bern. Grossmann’s father knew the director and was willing to recommend Einstein.

最终,爱因斯坦在苏黎世结交的另一位密友,即那位替他做数学笔记的同学格罗斯曼为他找到了一份意想不到的工作。正当爱因斯坦重陷绝望之时,格罗斯曼给他写信说,伯尔尼的瑞士专利局很可能有一个审查员的空岗。格罗斯曼的父亲认识专利局局长,愿意举荐爱因斯坦。

“I was deeply moved by your devotion and compassion, which did not let you forget your luckless friend,” Einstein replied. “I would be delighted to get such a nice job and that I would spare no effort to live up to your recommendation.” To Mari he exulted: “Just think what a wonderful job this would be for me! I’ll be mad with joy if something should come of that.”

he exulted: “Just think what a wonderful job this would be for me! I’ll be mad with joy if something should come of that.”

“你的热心和慈悲使我深受感动,这种品质使你没有忘记你不幸的朋友,”爱因斯坦回信说,“我很高兴能够得到一个这样好的工作,我将全力以赴,绝不辜负你的推荐。”他兴奋地对米列娃说:“你想想看,这对我是一个多么美妙的工作啊!要是这件事成了,我会高兴疯的!”

It would take months, he knew, before the patent-office job would materialize, assuming that it ever did. So he accepted a temporary post at a technical school in Winterthur for two months, filling in for a teacher on military leave. The hours would be long and, worse yet, he would have to teach descriptive geometry, neither then nor later his strongest field. “But the valiant Swabian is not afraid,” he proclaimed, repeating one of his favorite poetic phrases.30

他知道,即使专利局的工作成了,也要再等个把月才行。于是他在温特图尔(Winterthur)的一所技术学校找了一份临时的工作,暂时顶替一位休兵役假的教师。这个活儿不仅工期长,而且还要教画法几何,不论在当时还是以后,这一学科都不是爱因斯坦的强项。“可是这个勇敢的施瓦本人并不害怕”,他念念不忘这一心爱的诗句。

In the meantime, he and Mari would have the chance to take a romantic vacation together, one that would have fateful consequences.

would have the chance to take a romantic vacation together, one that would have fateful consequences.

与此同时,他和米列娃终于有机会共度一个浪漫的假期了,由此将产生一些重大的后果。

Lake Como, May 1901 科莫(Como)湖,1901年5月

“You absolutely must come see me in Como, you little witch,” Einstein wrote Mari at the end of April 1901. “You’ll see for yourself how bright and cheerful I’ve become and how all my brow-knitting is gone.”

at the end of April 1901. “You’ll see for yourself how bright and cheerful I’ve become and how all my brow-knitting is gone.”

“你绝对要到科莫来看我,你这个迷人的小妖精,”爱因斯坦1901年4月底写信给米列娃说,“你将会看到我已经变得多么活泼快乐,一切令人不愉快的事情都已经烟消云散啦。”

The family disputes and frustrating job search had caused him to be snappish, but he promised that was now over. “It was only out of nervousness that I was mean to you,” he apologized. To make it up to her, he proposed that they should have a romantic and sensuous tryst in one of the world’s most romantic and sensuous places: Lake Como, the grandest of the jewel-like Alpine finger lakes high on the border of Italy and Switzerland, where in early May the lush foliage bursts forth under majestic snow-capped peaks.

家庭的争吵与求职的受挫使他的脾气变得有些暴躁,不过他保证现在这一切都结束了。“过去我每次对你粗野只是由于烦躁。”他道歉说。为了做出补偿,他提出他们应当在世界上风景最优美、浪漫气息最浓郁的一个地方约会,这就是科莫湖,它位于意大利和瑞士的边境,是阿尔卑斯山诸多手指状湖泊中最大的一个。这些湖泊宛如宝石一般镶嵌在山间。每到5月初,在白雪皑皑的雄伟山峰之下,科莫湖周围的植物风华初绽,青葱欲滴。

“Bring my blue dressing-gown so we can wrap ourselves up in it,” he said. “I promise you an outing the likes of which you’ve never seen.”31

“把我的蓝色晨服带来,好把我们俩裹在里面,”他说,“我保证你从来没有经历过这样的旅行。”

Mari quickly accepted, but then changed her mind; she had received a letter from her family in Novi Sad “that robs me of all desire, not only for having fun, but for life itself.” He should make the trip on his own, she sulked.“It seems I can have nothing without being punished.” But the next day she changed her mind again. “I wrote you a little card yesterday while in the worst of moods because of a letter I received. But when I read your letter today I became a bit more cheerful, since I see how much you love me, so I think we’ll take that trip after all.”32

quickly accepted, but then changed her mind; she had received a letter from her family in Novi Sad “that robs me of all desire, not only for having fun, but for life itself.” He should make the trip on his own, she sulked.“It seems I can have nothing without being punished.” But the next day she changed her mind again. “I wrote you a little card yesterday while in the worst of moods because of a letter I received. But when I read your letter today I became a bit more cheerful, since I see how much you love me, so I think we’ll take that trip after all.”32

米列娃很快就答应了,但紧接着却改变了主意;家人从诺维萨德寄来的一封信“夺去了我所向往的一切,娱乐的兴致,也包括生活本身”。他只能自己去旅游了,米列娃满怀愠怒。“我似乎一想干点什么高兴的事就会受到惩罚。”不过第二天她又一次改变了想法。“昨天我在极其恶劣的心情下给你写了一张小明信片,那是由于我收到一封信的缘故。可是今天读了你的信,我又快乐了起来,因为我看到你是多么爱我,因此我想我们还是要去旅游的。”

And thus it was that early on the morning of Sunday, May 5, 1901, Albert Einstein was waiting for Mileva Mari at the train station in the village of Como, Italy, “with open arms and a pounding heart.” They spent the day there, admiring its gothic cathedral and walled old town, then took one of the stately white steamers that hop from village to village along the banks of the lake.

at the train station in the village of Como, Italy, “with open arms and a pounding heart.” They spent the day there, admiring its gothic cathedral and walled old town, then took one of the stately white steamers that hop from village to village along the banks of the lake.

就这样,1901年5月5日清晨,爱因斯坦在意大利的科莫村车站等候米列娃的到来。他“张开双臂,心里怦怦直跳”。这一天,他们先是欣赏了哥特式教堂和围墙之内的老城,然后登上了一艘豪华的白色游轮,沿湖饱览乡间美景。

They stopped to visit Villa Carlotta, the most luscious of all the famous mansions that dot the shore, with its frescoed ceilings, a version of Antonio Canova’s erotic sculpture Cupid and Psyche, and five hundred species of plants. Mari later wrote a friend how much she admired “the splendid garden, which I preserved in my heart, the more so because we were not allowed to swipe a single flower.”

later wrote a friend how much she admired “the splendid garden, which I preserved in my heart, the more so because we were not allowed to swipe a single flower.”

他们途中游览了卡尔洛塔庄园(VillaCarlotta),这是科莫湖沿岸所有著名宅第中最美的一个。那里不仅有天顶画,安东尼奥·卡诺瓦的色情雕塑“丘比特与普绪克”(Cupidand Psyche),而且还有500多种植物。米列娃后来给一个朋友写信说,她十分羨慕那座“富丽堂皇的花园,我已将它永存于心,因为我们连一枝花都不能拿走”。

After spending the night in an inn, they decided to hike through the mountain pass to Switzerland, but found it still covered with up to twenty feet of snow. So they hired a small sleigh,“the kind they use that has just enough room for two people in love with each other, and a coachman stands on a little plank in the rear and prattles all the time and calls you ‘signora,’ ” Mari wrote. “Could you think of anything more beautiful?”

wrote. “Could you think of anything more beautiful?”

在一家小旅馆留宿之后,他们决定通过山口到瑞士远足,但是发现路上仍然有厚达20英尺的积雪。所以他们租了一个小雪橇,“它的座位刚好容得下两个情投意合的人,在后面一块滑雪板上站着马车夫,他在这段时间里一直喋喋不休地闲聊,还称呼我‘太太’,”米列娃说,“你能想象比这更美妙的事吗?”

The snow was falling merrily, as far as the eye could see, “so that this cold, white infinity gave me the shivers and I held my sweetheart firmly in my arms under the coats and shawls covering us.” On the way down, they stomped and kicked at the snow to produce little avalanches, “so as to properly scare the world below.”33

雪还在轻快地下着,“这种冷飕飕、白茫茫的无边无垠使我瑟瑟发抖,在包裹我们的大衣和围巾下面,我将我的爱人紧紧抱住”。在下坡时,他们踢打着雪,造成一串串小雪崩,“为的是彻底镇住下面的世界”。

A few days later, Einstein recalled “how beautiful it was the last time you let me press your dear little person against me in that most natural way.”34 And in that most natural way, Mileva Mari became pregnant with Albert Einstein’s child.

became pregnant with Albert Einstein’s child.

几天以后,爱因斯坦回忆说:“上次的经历是多么美好啊,那时,我可以用最自然的方式将你这个亲爱的小人儿紧紧搂在怀里。”也正是以这种最自然的方式,米列娃·玛里奇怀上了阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦的孩子。

After returning to Winterthur, where he was a substitute teacher, Einstein wrote Mari a letter that made reference to her pregnancy. Oddly—or perhaps not oddly at all—he began by delving into matters scientific rather than personal.“I just read a wonderful paper by Lenard on the generation of cathode rays by ultraviolet light,” he started. “Under the influence of this beautiful piece I am filled with such happiness and joy that I must share some of it with you.” Einstein would soon revolutionize science by building on Lenard’s paper to produce a theory of light quanta that explained this photoelectric effect. Even so, it is rather surprising, or at least amusing, that when he rhapsodized about sharing “happiness and joy” with his newly pregnant lover, he was referring to a paper on beams of electrons.

a letter that made reference to her pregnancy. Oddly—or perhaps not oddly at all—he began by delving into matters scientific rather than personal.“I just read a wonderful paper by Lenard on the generation of cathode rays by ultraviolet light,” he started. “Under the influence of this beautiful piece I am filled with such happiness and joy that I must share some of it with you.” Einstein would soon revolutionize science by building on Lenard’s paper to produce a theory of light quanta that explained this photoelectric effect. Even so, it is rather surprising, or at least amusing, that when he rhapsodized about sharing “happiness and joy” with his newly pregnant lover, he was referring to a paper on beams of electrons.

在回到温特图尔继续任代课教师之后,爱因斯坦给米列娃写了一封信,信中提到了怀孕一事。奇怪的是(或者丝毫也不奇怪),他首先谈到的是科学而不是私人的事情。“我刚刚读了勒纳德的一篇讨论紫外线如何产生阴极射线的绝妙论文,”他在信的开头说,“由于受到这篇美文的感染,我心里的幸福和喜悦难以言表,以至于迫不及待要与你分享一些。”没过多久,爱因斯坦将在勒纳德论文的基础上提出光量子理论来解释光电效应,从而给科学带来革命。即便如此,他亟待与自己刚刚怀孕的恋人分享的“幸福和喜悦”竟然是指一篇讨论电子束的论文,这真是既令人惊异,又让人好笑。

Only after this scientific exultation came a brief reference to their expected child, whom Einstein referred to as a boy: “How are you darling? How’s the boy?” He went on to display an odd notion of what parenting would be like: “Can you imagine how pleasant it will be when we’re able to work again, completely undisturbed, and with no one around to tell us what to do!”

只是在这种科学的狂喜之后,他才简短地提及了他们即将出生的孩子:“亲爱的,你的情况怎么样?小家伙好么?”接着,他就育儿生活的情形提出了一种奇特的说法:“想想看,要是我们又能不受干扰地在一起工作,周围没有人对我们指手画脚,那将多么令人愉快啊!”

Most of all, he tried to be reassuring. He would find a job, he pledged, even if it meant going into the insurance business. They would create a comfortable home together. “Be happy and don’t fret, darling. I won’t leave you and will bring everything to a happy conclusion. You just have to be patient! You will see that my arms are not so bad to rest in, even if things are beginning a little awkwardly.”35

这封信主要还是为了安抚米列娃。他发誓自己会找到工作,哪怕是进入一家保险公司。他们的生活很快就会安稳。“要满怀信心,亲爱的,绝不要闷闷不乐。我可不会离开你,而且还会使一切都有美满的结局。你现在只需保持耐心就可以了!你将会看到,倚靠着我的臂膀并不坏,即使事情开始时有点糟糕”。

Mari was preparing to retake her graduation exams, and she was hoping to go on to get a doctorate and become a physicist. Both she and her parents had invested enormous amounts, emotionally and financially, in that goal over the years. She could have, if she had wished, terminated her pregnancy. Zurich was then a center of a burgeoning birth control industry, which included a mail-order abortion drug firm based there.

was preparing to retake her graduation exams, and she was hoping to go on to get a doctorate and become a physicist. Both she and her parents had invested enormous amounts, emotionally and financially, in that goal over the years. She could have, if she had wished, terminated her pregnancy. Zurich was then a center of a burgeoning birth control industry, which included a mail-order abortion drug firm based there.

米列娃准备重考毕业考试了,她希望自己将来能够获得博士头衔,成为物理学家。多年以来,她和父母都为此倾注了大量心血,投入了不少财力。如果她愿意,她本可以终止妊娠。苏黎世当时是节育产业最兴旺的地区之一,有一家流产药物公司的总部就设在那里,可以提供邮购服务。

Instead, she decided that she wanted to have Einstein’s child—even though he was not yet ready or willing to marry her. Having a child out of wedlock was rebellious, given their upbringings, but not uncommon. The official statistics for Zurich in 1901 show that 12 percent of births were illegitimate. Residents who were Austro-Hungarian, moreover, were much more likely to get pregnant while unmarried. In southern Hungary, 33 percent of births were illegitimate. Serbs had the highest rate of illegitimate births, Jews by far the lowest.36

然而,她还是决定生下这个孩子,即使爱因斯坦还没有做好同她结婚的准备。就他们的教养而言,有私生子是叛逆的,但这并非罕见。苏黎世官方的统计数据表明,在1901年有12%的孩子是私生的。而且奥匈帝国的居民更有可能未婚先孕。在匈牙利南部,有二分之一的孩子是私生的。塞尔维亚人的私生率最高,犹太人则最低。

The decision caused Einstein to focus on the future. “I will look for a position immediately, no matter how humble it is,” he told her. “My scientific goals and my personal vanity will not prevent me from accepting even the most subordinate position.” He decided to call Besso’s father as well as the director of the local insurance company, and he promised to marry her as soon as he settled into a job. “Then no one can cast a stone on your dear little head.”

这一决定使爱因斯坦不得不为将来做一番打算。“我要立即谋取一个职位,不管它是怎样的差劲,”他说,“我的科学目标和个人的虚荣自负都不会妨碍我接受哪怕级别最低的职位。”他决定与贝索的父亲以及当地保险公司的负责人联系,并且许诺一旦工作落实,就尽快与米列娃结婚,“那样就没有人能向你可爱的小脑瓜儿扔石头了”。

The pregnancy could also resolve, or so he hoped, the issues they faced with their families. “When your parents and mine are presented with a fait accompli, they’ll just have to reconcile themselves to it as best they can.”37

他也希望怀孕这件事能够化解双方家庭面临的问题。“你我的父母一旦面对既成事实,也就只能尽量迁就了。”

Mari , bedridden in Zurich with pregnancy sickness, was thrilled. “So, sweetheart, you want to look for a job immediately? And have me move in with you!” It was a vague proposal, but she immediately pronounced herself “happy” to agree. “Of course it mustn’t involve accepting a really bad position, darling,” she added. “That would make me feel terrible.” At her sister’s suggestion she tried to convince Einstein to visit her parents in Serbia for the summer vacation. “It would make me so happy,” she begged. “And when my parents see the two of us physically in front of them, all their doubts will evaporate.”38

, bedridden in Zurich with pregnancy sickness, was thrilled. “So, sweetheart, you want to look for a job immediately? And have me move in with you!” It was a vague proposal, but she immediately pronounced herself “happy” to agree. “Of course it mustn’t involve accepting a really bad position, darling,” she added. “That would make me feel terrible.” At her sister’s suggestion she tried to convince Einstein to visit her parents in Serbia for the summer vacation. “It would make me so happy,” she begged. “And when my parents see the two of us physically in front of them, all their doubts will evaporate.”38

这时,米列娃在苏黎世因怀孕而卧床不起,她在接到这封能是一周左右之后。 信后激动不已。“怎么,亲爱的,你打算立即找个事做?那就接我到你那里去吧!”这是个含混的求婚,但她立即宣布自己“乐于”接受。“亲爱的,当然不能接受一个糟糕透顶的职位,”她又说,“那会让我很难受的。”根据姐姐的建议,她试图说服爱因斯坦暑假期间去塞尔维亚拜访她的父母。“那样我会喜出望外的,”她恳求说,“当我的双亲看到我们俩活生生地出现在他们面前时,他们的所有疑虑就会烟消云散了。”

But Einstein, to her dismay, decided to spend the summer vacation again with his mother and sister in the Alps. As a result, he was not there to help and encourage her at the end of July 1901 when she re-took her exams. Perhaps as a consequence of her pregnancy and personal situation, Mileva ended up failing for the second time, once again getting a 4.0 out of 6 and once again being the only one in her group not to pass.

但令她失望的是,爱因斯坦决定再次和他的父母在阿尔卑斯山过暑假。结果在1901年7月底,当米列娃第二次参加毕业考试时,爱因斯坦并没有在那里帮助和鼓励她。或许是由于怀孕和身体状况所致,她这次又没能通过考试,不仅分数依然是4.0/6,而且也是那个组里唯一没有通过考试的人。

Thus it was that Mileva Mari found herself resigned to giving up her dream of being a scientific scholar. She visited her home in Serbia—alone—and told her parents about her academic failure and her pregnancy. Before leaving, she asked Einstein to send her father a letter describing their plans and, presumably, pledging to marry her. “Will you send me the letter so I can see what you’ve written?” she asked. “By and by I’ll give him the necessary information, the unpleasant news as well.”39

found herself resigned to giving up her dream of being a scientific scholar. She visited her home in Serbia—alone—and told her parents about her academic failure and her pregnancy. Before leaving, she asked Einstein to send her father a letter describing their plans and, presumably, pledging to marry her. “Will you send me the letter so I can see what you’ve written?” she asked. “By and by I’ll give him the necessary information, the unpleasant news as well.”39

于是,米列娃只好放弃了成为科学研究者的梦想,只身一人回到塞尔维亚的家中,告诉父母她的怀孕和考试不及格。临行前,她要爱因斯坦寄给她父亲一封信描述他们的计划,并且如果可能,发誓会娶她。“你可否把那封信寄给我,我也好看看你写了什么?”她问,“我不久会告诉他必要的信息,还有那些令人不快的事情。”

Disputes with Drude and Others 与德鲁德等人的论争

Einstein’s impudence and contempt for convention, traits that were abetted by Mari , were evident in his science as well as in his personal life in 1901. That year, the unemployed enthusiast engaged in a series of tangles with academic authorities.

, were evident in his science as well as in his personal life in 1901. That year, the unemployed enthusiast engaged in a series of tangles with academic authorities.

爱因斯坦对传统的冒犯和蔑视得到了米列娃的纵容。1901年,这些特点在他的科学和个人生活中表现得异常显著。在这一年,这位失业的狂热分子卷入了4场与学术权威的纷争之中。

The squabbles show that Einstein had no qualms about challenging those in power. In fact, it seemed to infuse him with glee. As he proclaimed to Jost Winteler in the midst of his disputes that year, “Blind respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth.” It would prove a worthy credo, one suitable for being carved on his coat of arms if he had ever wanted such a thing.

这些争吵表明,爱因斯坦会毫不犹豫地向权威发出挑战。事实上,这似乎给他带来了极大的愉悦。正如他那年对约斯特·温特勒宣称的那样:“对权威的盲目崇拜是真理的最大敌人。”事实证明,这一可敬的信条价值非凡。如果他愿意,这句话很适合刻在他的盾徽上。

His struggles that year also reveal something more subtle about Einstein’s scientific thinking: he had an urge—indeed, a compulsion—to unify concepts from different branches of physics. “It is a glorious feeling to discover the unity of a set of phenomena that seem at first to be completely separate,” he wrote to his friend Grossmann as he embarked that spring on an attempt to tie his work on capillarity to Boltzmann’s theory of gases. That sentence, more than any other, sums up the faith that underlay Einstein’s scientific mission, from his first paper until his last scribbled field equations, guiding him with the same sure sense that was displayed by the needle of his childhood compass.40

他在这一年的努力还揭示了其科学思想的一些微妙之处:他有一种驱动力或冲动,希望将各个物理学分支中的概念统一起来。他将诸理论之间显示出来的矛盾视为需要进一步研究的标志。“从初看起来完全无关的一系列现象中发现统一性,那真是一种壮美的感觉。”他给老朋友格罗斯曼写信说,那时他正尝试将自己关于毛细现象的工作与玻尔兹曼的气体理论联系起来。较之其他,这句话更能概括爱因斯坦科学使命背后的信念。从他的第一篇论文起,一直到生命最后一刻涂写的场方程,这种指导性的信念贯穿始终,就像他童年时在指南针上所感受到的那种确定性一样。

Among the potentially unifying concepts that were mesmerizing Einstein, and much of the physics world, were those that sprang from kinetic theory, which had been developed in the late nineteenth century by applying the principles of mechanics to phenomena such as heat transfer and the behavior of gases. This involved regarding a gas, for example, as a collection of a huge number of tiny particles—in this case, molecules made up of one or more atoms—that careen around freely and occasionally collide with one another.

在令爱因斯坦着迷的具有潜在统一性的诸多概念中,有一些源自分子运动论,这一理论是19世纪晚期通过将力学原理应用于热传导和气体状态等现象而发展起来的。例如,它将气体看成大量微小粒子——这里是由若干原子构成的分子——的集合,这些粒子自由地四处运动,不时与其他粒子发生碰撞。

Kinetic theory spurred the growth of statistical mechanics, which describes the behavior of a large number of particles using statistical calculations. It was, of course, impossible to trace each molecule and each collision in a gas, but knowing the statistical behavior gave a workable theory of how billions of molecules behaved under varying conditions.

分子运动论促进了统计力学的发展,后者用统计计算来描述大量粒子的行为。当然,它不可能把气体中的每一个分子和每一次碰撞都搞清楚,但是如果知道了统计行为和平均运动,就可以用一种切实可行的理论来描述大量分子在不同条件下如何活动。

Scientists proceeded to apply these concepts not only to the behavior of gases, but also to phenomena that occurred in liquids and solids, including electrical conductivity and radiation. “The opportunity arose to apply the methods of the kinetic theory of gases to completely different branches of physics,” Einstein’s close friend Paul Ehrenfest, himself an expert in the field, later wrote.“Above all, the theory was applied to the motion of electrons in metals, to the Brownian motion of microscopically small particles in suspensions, and to the theory of blackbody radiation.”41

科学家们不仅用这些概念来描述气体状态,而且还用它来描述液体和固体现象,比如电导率和辐射。“将气体分子运动论方法应用于完全不同的物理学分支的时机到了,”爱因斯坦的密友保罗·埃伦菲斯特(他本人也是该领域的专家)后来写道,“该理论首先应当运用于金属电子的运动,微观悬浮粒子的布朗运动以及黑体辐射理论。”

Although many scientists were using atomism to explore their own specialties, for Einstein it was a way to make connections, and develop unifying theories, between a variety of disciplines. In April 1901, for example, he adapted the molecular theories he had used to explain the capillary effect in liquids and applied them to the diffusion of gas molecules. “I’ve got an extremely lucky idea, which will make it possible to apply our theory of molecular forces to gases as well,” he wrote Mari . To Grossmann he noted, “I am now convinced that my theory of atomic attractive forces can also be extended to gases.”42

. To Grossmann he noted, “I am now convinced that my theory of atomic attractive forces can also be extended to gases.”42

虽然当时许多科学家正在用原子论探索他们各自从事的研究领域,但在爱因斯坦看来,可以用它在不同学科之间建立联系,构造统一理论。例如,1901年4月,他对用来解释液体毛细现象的分子理论进行了改造,将它运用于气体分子的扩散。“我已经有了一个极其出色的想法,它使得我们的分子力理论也可以应用于气体。”他写信给米列娃。他也对格罗斯曼说:“我现在确信,我的原子吸引力理论也可以推广到气体。”

Next he became interested in the conduction of heat and electricity, which led him to study Paul Drude’s electron theory of metals. As the Einstein scholar Jürgen Renn notes, “Drude’s electron theory and Boltzmann’s kinetic theory of gas do not just happen to be two arbitrary subjects of interest to Einstein, but rather they share an important common property with several other of his early research topics: they are two examples of the application of atomistic ideas to physical and chemical problems.”43

接下来,他对导热和导电现象产生了兴趣,这使他开始研究保罗·德鲁德的金属电子理论。正如爱因斯坦研究专家雷恩所指出的:“爱因斯坦对德鲁德的电子理论和玻尔兹曼的气体分子运动论感兴趣并非缘于巧合,或是随随便便的选择,而是因为它们与他早期的几个研究主题有一种重要的共性,那就是,它们是将原子论思想应用于物理化学问题的两个例子。”

Drude’s electron theory posited that there are particles in metal that move freely, as molecules of gas do, and thereby conduct both heat and electricity. When Einstein looked into it, he was pleased with it in parts. “I have a study in my hands by Paul Drude on the electron theory, which is written to my heart’s desire, even though it contains some very sloppy things,” he told Mari . A month later, with his usual lack of deference to authority, he declared, “Perhaps I’ll write to Drude privately to point out his mistakes.”

. A month later, with his usual lack of deference to authority, he declared, “Perhaps I’ll write to Drude privately to point out his mistakes.”

德鲁德的电子理论认为,金属中存在着像气体分子一样自由运动的粒子,因此可以导热和导电。爱因斯坦在研究这个问题时,在一定程度上赞同这种观点。“我手头有德鲁德的一篇关于电子理论的论文,它完全写出了我的心里话,虽然其中也包含一些非常草率的地方。”他对米列娃说。一个月以后,带着那种对权威的一贯的不尊重,他宣称:“也许我会亲自给德鲁德写信,指出他的错误。”

And so he did. In a letter to Drude in June,Einstein pointed out what he thought were two mistakes.“He will hardly have anything sensible to refute me with,” Einstein gloated to Mari , “because my objections are very straightforward.” Perhaps under the charming illusion that showing an eminent scientist his purported lapses is a good method for getting a job, Einstein included a request for one in his letter.44

, “because my objections are very straightforward.” Perhaps under the charming illusion that showing an eminent scientist his purported lapses is a good method for getting a job, Einstein included a request for one in his letter.44

他的确这样做了。在6月给德鲁德的信中,爱因斯坦指出了他所认为的两个错误。“他几乎不可能提出任何合理的意见来反驳我,”爱因斯坦扬扬自得地对米列娃说,“因为我的批评简单明了。”或许是出于一种美妙的幻觉,爱因斯坦以为向一位著名科学家指出他的失误是谋职的一个好方法,所以他在信中提出了这一请求。

Surprisingly, Drude replied. Not surprisingly, he dismissed Einstein’s objections. Einstein was outraged. “It is such manifest proof of the wretchedness of its author that no further comment by me is necessary,” Einstein said when forwarding Drude’s reply to Mari . “From now on I’ll no longer turn to such people, and will instead attack them mercilessly in the journals, as they deserve. It is no wonder that little by little one becomes a misanthrope.”

. “From now on I’ll no longer turn to such people, and will instead attack them mercilessly in the journals, as they deserve. It is no wonder that little by little one becomes a misanthrope.”

出乎意料的是,德鲁德竟然回信了。毫不奇怪,他拒绝接受爱因斯坦的反对意见。德鲁德的回信令爱因斯坦火冒三丈。“对于其作者的卑劣可耻,它倒是一份确实可靠的证据,无须我补充任何说明,”爱因斯坦在把这封信转给米列娃时说,“从现在起我绝不会再向这样的人求助,而是要在期刊上无情地抨击他们。难怪人会渐渐变得遁世,不愿与他人交往。”

Einstein also vented his frustration to Jost Winteler, his father figure from Aarau, in a letter that included his declaration about a blind respect for authority being the greatest enemy of truth. “He responds by pointing out that another ‘infallible’ colleague of his shares his opinion. I’ll soon make it hot for the man with a masterly publication.”45

关于这次受挫,爱因斯坦还在一封信中向阿劳的约斯特·温特勒发泄了他的愤怒。也正是在这封信中,他宣称对权威的盲目崇拜是真理的最大敌人。“他竟然回应我说,他的另一位‘不可能出错的’同事也持相同看法。我不久就要发表一篇巧妙的文章,让这个人下不来台。”

The published papers of Einstein do not identify this “infallible” colleague cited by Drude, but some sleuthing by Renn has turned up a letter from Mari that declares it to be Ludwig Boltzmann.46 That explains why Einstein proceeded to immerse himself in Boltzmann’s writings. “I have been engrossed in Boltzmann’s works on the kinetic theory of gases,” he wrote Grossmann in September, “and these last few days I wrote a short paper myself that provides the missing key-stone in the chain of proofs that he started.”47

that declares it to be Ludwig Boltzmann.46 That explains why Einstein proceeded to immerse himself in Boltzmann’s writings. “I have been engrossed in Boltzmann’s works on the kinetic theory of gases,” he wrote Grossmann in September, “and these last few days I wrote a short paper myself that provides the missing key-stone in the chain of proofs that he started.”47

业已出版的爱因斯坦书稿并未确定德鲁德所说的这位“不可能出错的”同事是谁,不过根据雷恩的发现,有米列娃的一页未公开的信上说,这个人就是玻尔兹曼。这解释了为什么爱因斯坦开始着手研究玻尔兹曼的著作。“近来我认真研究了玻尔兹曼关于气体分子运动论的著作,”他9月给格罗斯曼写信说,“前几天我自己还写了一篇小论文,为他所提出的一连串证明提供缺失的楔石(keystone)。”

Boltzmann, then at the University of Leipzig, was Europe’s master of statistical physics. He had helped to develop the kinetic theory and defend the faith that atoms and molecules actually exist. In doing so, he found it necessary to reconceive the great Second Law of Thermodynamics. This law has many equivalent formulations. It says that heat flows naturally from hot to cold, but not the reverse. Another way to describe the Second Law is in terms of entropy, the degree of disorder and randomness in a system. Any spontaneous process tends to increase the entropy of a system. For example, perfume molecules drift out of an open bottle and into a room but don’t, at least in our common experience, spontaneously gather themselves together and all drift back into the bottle.

玻尔兹曼当时在莱比锡大学,是欧洲统计物理学的巨擘。他帮助发展了气体分子运动论,捍卫了原子、分子实际存在的信念。在这一过程中,他发现有必要重新构想伟大的热力学第二定律。这个定律有许多等价的表述。比如说,热必然会由热的物体流向冷的物体,但却不会自发地由冷的物体流向热的物体。另一种方式是借助熵(表示一个系统无序和随机的程度)来表述,即任何一个自发过程都倾向于增加系统的熵。例如,香水分子可以从敞开的瓶中飘进房间,但至少在我们的日常经验中,它们不会自动聚拢到瓶中。

The problem for Boltzmann was that mechanical processes, such as molecules bumping around, could each be reversed, according to Newton. So a spontaneous decrease in entropy would, at least in theory, be possible. The absurdity of positing that diffused perfume molecules could gather back into a bottle, or that heat could flow from a cold body to a hot one spontaneously, was flung against Boltzmann by opponents, such as Wilhelm Ostwald, who did not believe in the reality of atoms and molecules. “The proposition that all natural phenomena can ultimately be reduced to mechanical ones cannot even be taken as a useful working hypothesis: it is simply a mistake,” Ostwald declared. “The irreversibility of natural phenomena proves the existence of processes that cannot be described by mechanical equations.”

玻尔兹曼的问题是,根据牛顿的理论,像分子碰撞这样的每一个力学过程都是可逆的,因此熵的自发减少至少理论上是可能的。玻尔兹曼的反对者认为,假设扩散的香水分子可以自发地聚拢到瓶中,或者热可以自动从冷的物体流到热的物体中,那都是荒谬绝伦的。奥斯特瓦尔德便是这样一位反对者,他不相信原子和分子的实在性。“‘一切自然现象最终都可以归结为力学现象’这一命题甚至连有用的初步假说都算不上,它完完全全是个错误,”奥斯特瓦尔德宣称,“自然现象的不可逆性证明,存在着一些无法用力学方程来解释的过程。”

Boltzmann responded by revising the Second Law so that it was not absolute but merely a statistical near-certainty. It was theoretically possible that millions of perfume molecules could randomly bounce around in a way that they all put themselves back into a bottle at a certain moment, but that was exceedingly unlikely, perhaps trillions of times less likely than that a new deck of cards shuffled a hundred times would end up back in its pristine rank-and-suit precise order.48

为此,玻尔兹曼对热力学第二定律进行了改造,使得它并非在绝对意义上确定,而仅仅满足统计上的近似确定性。从理论上讲,数百万个香水分子的确有可能通过随机弹跳在某一时刻全部回到瓶中,只不过这种情况发生的可能性微乎其微,其可能性或许比一副新纸牌洗一百次后重新回到原初的花色和大小序列还要小,是它的数万亿分之一。

When Einstein rather immodestly declared in September 1901 that he was filling in a “keystone” that was missing in Boltzmann’s chain of proofs, he said he planned to publish it soon. But first, he sent a paper to the Annalen der Physik that involved an electrical method for investigating molecular forces, which used calculations derived from experiments others had done using salt solutions and an electrode.49

1901年9月,爱因斯坦相当不客气地宣称自己正在填补玻尔兹曼一连串证明中的“楔石”,而且说很快就会将它发表。不过在次年4月,他给《物理学纪事》寄了一篇论文,其中涉及一种研究分子力的电学方法,它利用了别人用盐液和电极所做实验得出的计算结果。

Then he published his critique of Boltzmann’s theories. He noted that they worked well in explaining heat transfer in gases but had not yet been properly generalized for other realms. “Great as the achievements of the kinetic theory of heat have been in the domain of gas theory,” he wrote, “the science of mechanics has not yet been able to produce an adequate foundation for the general theory of heat.” His aim was “to close this gap.”50

接着,他发表了对玻尔兹曼理论的批评。他指出,玻尔兹曼的理论可以很好地解释气体的热传递,但却没有推广到其他领域。“尽管热的分子运动论在气体理论方面取得了很大成就,”他写道,“可是到目前为止,力学还未能为一般的热学理论提供恰当基础。”他的目标就是要“填补这一缺陷”。

This was all quite presumptuous for an undistinguished Polytechnic student who had not been able to get either a doctorate or a job. Einstein himself later admitted that these papers added little to the body of physics wisdom. But they do indicate what was at the heart of his 1901 challenges to Drude and Boltzmann. Their theories, he felt, did not live up to the maxim he had proclaimed to Grossmann earlier that year about how glorious it was to discover an underlying unity in a set of phenomena that seem completely separate.

对于一个既未获得博士学位,又没有找到工作的名不见经传的联邦工学院学生来说,这一切过于放肆了。爱因斯坦后来承认,这些论文并没有为整个物理学大厦添砖加瓦。不过它们的确表明了他1901年挑战德鲁德和玻尔兹曼的核心是什么。他感觉他们的理论并没有实现他当年向格罗斯曼宣称的那种准则,即透过似乎完全无关的现象发现其背后蕴藏的美妙统一性。

In the meantime, in November 1901, Einstein had submitted an attempt at a doctoral dissertation to Professor Alfred Kleiner at the University of Zurich. The dissertation has not survived, but Mari told a friend that “it deals with research into the molecular forces in gases using various known phenomena.” Einstein was confident. “He won’t dare reject my dissertation,” he said of Kleiner, “otherwise the shortsighted man is of little use to me.”51

told a friend that “it deals with research into the molecular forces in gases using various known phenomena.” Einstein was confident. “He won’t dare reject my dissertation,” he said of Kleiner, “otherwise the shortsighted man is of little use to me.”51

与此同时,爱因斯坦1901年11月向苏黎世大学的阿尔弗雷德·克莱纳教授提交了一篇博士论文。这篇论文没有留存下来,但米列娃对一位朋友说:“它涉及用各种已知现象研究分子力。”爱因斯坦信心十足。“他不敢拒绝我的博士论文,”他谈到克莱纳时说,“在其他方面,跟这个目光短浅的人没有什么交道好打。”

By December Kleiner had not even responded, and Einstein started worrying that perhaps the professor’s “fragile dignity” might make him uncomfortable accepting a dissertation that denigrated the work of such masters as Drude and Boltzmann. “If he dares to reject my dissertation, then I’ll publish his rejection along with my paper and make a fool of him,” Einstein said. “But if he accepts it, then we’ll see what good old Herr Drude has to say.”

到了12月,克莱纳仍然没有回音,爱因斯坦开始担心这位教授是不是由于“脆弱的尊严”而不好接受这样一篇论文,因为它贬低了像德鲁德和玻尔兹曼这样的大师的工作。“要是他真敢拒绝我的博士论文,我就把他的拒绝连同这篇论文一道白纸黑字地发表出来,让他当众出丑,”爱因斯坦说,“不过要是他接受了,我倒要看看那位德鲁德老先生会怎么说。”

Eager for a resolution, he decided to go see Kleiner personally. Rather surprisingly, the meeting went well. Kleiner admitted he had not yet read the dissertation, and Einstein told him to take his time. They then proceeded to discuss various ideas that Einstein was developing, some of which would eventually bear fruit in his relativity theory. Kleiner promised Einstein that he could count on him for a recommendation the next time a teaching job came up. “He’s not quite as stupid as I’d thought,” was Einstein’s verdict.“Moreover, he’s a good fellow.”52

由于迫切希望有个了结,他决定亲自去见克莱纳。出乎意料的是,这次会面相当顺利。克莱纳承认他还没有读这篇论文,爱因斯坦让他不要着急,慢慢看。接着他们讨论了爱因斯坦提出的各种想法,其中一些后来用在了狭义相对论中。克莱纳向爱因斯坦保证,如果将来有获得教职的机会,他一定帮忙写推荐信。爱因斯坦的结论是:“他并不像我想象的那样昏庸,而且,他是一个好伙伴。”

Kleiner may have been a good fellow, but he did not like Einstein’s dissertation when he finally got around to reading it. In particular, he was unhappy about Einstein’s attack on the scientific establishment. So he rejected it; more precisely, he told Einstein to withdraw it voluntarily, which permitted him to get back his 230 franc fee. According to a book written by Einstein’s stepson-in-law, Kleiner’s action was “out of consideration to his colleague Ludwig Boltzmann, whose train of reasoning Einstein had sharply criticized.” Einstein, lacking such sensitivity, was persuaded by a friend to send the attack directly to Boltzmann.53

克莱纳也许的确是一个好伙伴,不过他在读完爱因斯坦的论文之后并不喜欢。特别是,爱因斯坦对科学权威人士的抨击使他感到不悦,所以他拒绝了这篇论文。他对爱因斯坦说,论文可以自愿撤回,并可取回230法郎的评审费。根据爱因斯坦的继子在一本书中的说法,克莱纳的举动是“顾及其同事玻尔兹曼,因为爱因斯坦就玻尔兹曼的一系列推理提出了尖锐的批评”。而缺乏这种敏感的爱因斯坦则被朋友说服,将这篇论文直接寄给了玻尔兹曼。

Lieserl 莉色儿

Marcel Grossmann had mentioned to Einstein that there was likely to be a job at the patent office for him, but it had not yet materialized. So five months later, he gently reminded Grossmann that he still needed help. Noticing in the newspaper that Grossmann had won a job teaching at a Swiss high school, Einstein expressed his “great joy” and then plaintively added, “I, too, applied for that position, but I did it only so that I wouldn’t have to tell myself that I was too faint-hearted to apply.”54