The “Financial Revolution”

第三部分 金融革命一 金融革命

The importance of finance and of a productive economic base which created revenues for the state was already clear to Renaissance princes, as the previous chapter has illustrated. The rise of the ancien régime monarchies of the eighteenth century, with their large military establishments and fleets of warships, simply increased the government’s need to nurture the economy and to create financial institutions which could raise and manage the monies concerned. 4 Moreover, like the First World War, conflicts such as the seven major Anglo-French wars fought between 1689 and 1815 were struggles of endurance. Victory therefore went to the Power—or better, since both Britain and France usually had allies, to the Great Power coalition—with the greater capacity to maintain credit and to keep on raising supplies. The mere fact that these were coalition wars increased their duration, since a belligerent whose resources were fading would look to a more powerful ally for loans and reinforcements in order to keep itself in the fight. Given such expensive and exhausting conflicts, what each side desperately required was—to use the old aphorism—“money, money, and yet more money. ” It was this need which formed the background to what has been termed the “financial revolution” of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries,5 when certain western European states evolved a relatively sophisticated system of banking and credit in order to pay for their wars.

如上一章所述,文艺复兴时期的王公们已清楚地认识到为国家创收的生产性经济基础和财政的重要性。18世纪旧君主政体兴起,他们拥有庞大的军队和众多战舰组成的舰队。这些又促使政府发展经济,增强筹措和管理有关资金的财政机构。不仅如此,1689—1805年英法间的7场大战,如同第一次世界大战一样,是持久战。因而胜利总是属于更有能力保持信誉、持续获得给养的大国,确切地说由于英国同法国都有盟国,胜利常常属于大国的联盟。事实上,这种联盟之间的战争只增加了战争的持久性,因为交战一方若资源耗尽,还可以向更强大的盟国寻求贷款和支援以维持作战。在这种花费巨大和耗竭资源的战争中,各方迫切需要的,是“钱,钱,更多的钱”。正是这种需要成了17世纪末和18世纪初所谓“财政革命”的背景。当时一些西欧国家为支付其战争费用,发展了一套复杂的银行和信贷系统。

There was, it is true, a second and nonmilitary reason for the financial changes of this time. That was the chronic shortage of specie, particularly in the years before the gold discoveries in Portuguese Brazil in 1693. The more European commerce with the Orient developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the greater the outflow of silver to cover the trade imbalances, causing merchants and dealers everywhere complain of the scarcity of coin. In addition, the steady increases in European commerce, especially in essential products such as cloth and naval stores, together with the tendency for the seasonal fairs of medieval Europe to be replaced by permanent centers of exchange, led to a growing regularity and predictability of financial settlements and thus to the greater use of bills of exchange and notes of credit. In Amsterdam especially, but also in London, Lyons, Frankfurt, and other cities, there arose a whole cluster of moneylenders, commodity dealers, goldsmiths (who often dealt in loans), bill merchants, and jobbers in the shares of the growing number of joint-stock companies. Adopting banking practices which were already in evidence in Renaissance Italy, these individuals and financial houses steadily created a structure of national and international credit to underpin the early modern world economy.

的确,这个时期的财政变化还有第二位的、非军事的原因,那就是硬币的长期匮乏,特别是1693年葡属巴西发现金矿之前的那些年。在17和18世纪,欧洲同东方的贸易越发展,越有更多的白银为支付贸易逆差而外流。各地的大小商人都在抱怨缺乏硬币。此外,欧洲贸易的增长,特别是如布匹和航海用品等大宗产品贸易的持续增长,加之永久性贸易中心代替中世纪欧洲的季节性交易市场,使财务结算的规则性和可靠性增强。这就大大增加了汇票和信用票证的使用。特别是在阿姆斯特丹,此外还有伦敦、里昂、法兰克福及其他城市,出现了一大批放款人、商品经销人、金匠(他们经常放债)、证券经纪人,以及数目日益增加的联合股份公司的经纪人。这些金融业者和钱庄采用文艺复兴时期在意大利已经出现的金融业习惯做法,逐步建立起一套支撑着近代早期世界经济的国家的和国际的信贷体制。

Nevertheless, by far the largest and most sustained boost to the “financial revolution” in Europe was given by war. If the difference between the financial burdens of the age of the Philip II and that of Napoleon was one of degree, it still was remarkable enough. The cost of a sixteenth-century war could be measured in millions of pounds; by the late-seventeenth century, it had risen to tens of millions of pounds; and at the close of the Napoleonic War the outgoings of the major combatants occasionally reached a hundred million pounds a year. Whether these prolonged and frequent clashes between the Great Powers, when translated into economic terms, were more of a benefit to than a brake upon the commercial and industrial rise of the West can never be satisfactorily resolved. The answer depends, to a great extent, upon whether one is trying to assess the absolute growth of a country as opposed to its relative prosperity and strength before and after a lengthy conflict. 6 What is clear is that even the most thriving and “modern” of the eighteenth-century states could not immediately pay for the wars of this period out of their ordinary revenue. Moreover, vast rises in taxes, even if the machinery existed to collect them, could well provoke domestic unrest, which all regimes feared—especially when facing foreign challengers at the same time.

但是,还是战争给予欧洲“金融革命”以最大、最持久的推动。如果说费利普二世时期和拿破仑时期财政负担只是程度上的差别的话,那么这种差别也是相当可观的。在16世纪打一场战争只要几百万英镑,到了17世纪末,打一场战争要几千万英镑;而在拿破仑战争末期,主要交战国的开支有时一年就达上亿英镑。如果从经济角度来看,大国间这些旷日持久、此起彼伏的冲突对西方商业和工业的发展是否利大于弊,这是永远也不可能满意地加以解决的问题。在很大程度上,答案取决于你是否以长期战争前后的相对繁荣和实力作参照,竭力估算出一个国家的绝对增长。有一点很清楚,即使在18世纪中称得上最繁荣、最“现代化”的国家,全靠其平时的正常收入也不够支付它在这个时期所进行的战争。事情远未到此为止,大幅度地提高税收,即使有现成的机构去征收,也很可能触发国内的动乱。这正是所有政权都为之提心吊胆的事情,特别是在同时面临外国挑战者的时候。

Consequently, the only way a government could finance a war adequately was by borrowing: by selling bonds and offices, or better, negotiable long-term stock paying interest to all who advanced monies to the state. Assured of an inflow of funds, officials could then authorize payments to army contractors, provision merchants, shipbuilders, and the armed services themselves. In many respects, this two-way system of raising and simultaneously spending vast sums of money acted like a bellows, fanning the development of western capitalism and of the nation-state itself.

其结果是,各国政府为战争筹措足够资金的唯一办法就是借款,即通过出售债券和官制,或者更好的办法是向那些借钱给国家的人出售偿本付息、可以流通的长期公债券。有了资金来源的保障之后,官员们就有能力支付军火商、供应给养的商人、造船主以及军队的官兵们。从许多方面来说,这种一边大量借钱,一边大量花钱的双向体制就像是一个风箱,给西方资本主义制度和民族国家本身的发展吹风打气。

Yet however natural all this may appear to later eyes, it is important to stress that the success of such a system depended on two critical factors: reasonably efficient machinery for raising loans, and the maintenance of a government’s “credit” in the financial markets. In both respects, the United Provinces led the way—not surprisingly, since the merchants there were part of the government and desired to see the affairs of state managed according to the same principles of financial rectitude as applied in, say, a joint-stock company. It was therefore appropriate that the States General of the Netherlands, which efficiently and regularly raised the taxes to cover governmental expenditures, was able to set interest rates very low, thus keeping down debt repayments. This system, superbly reinforced by the many financial activities of the city of Amsterdam, soon gave the United Provinces an international reputation for clearing bills, exchanging currency, and providing credit, which naturally created a structure—and an atmosphere—within which longterm funded state debt could be regarded as perfectly normal. So successfully did Amsterdam become a center of Dutch “surplus capital” that it soon was able to invest in the stock of foreign companies and, most important of all, to subscribe to a whole variety of loans floated by foreign governments, especially in wartime. 7

不论对后世的人来说这是多么自然的事情,还是有必要强调这个体制的成功仰仗的两个关键因素:足够有效的筹措贷款的机构;在金融市场上维持政府的“信誉”。在这两个方面,联合省都做得很出色。这倒没什么奇怪的,荷兰的商人们是政府的组成部分,他们希望像管理一家联合股份公司一样,用同样不打折扣的财政原理来管理国家。因而为政府开支定期地高效率征收赋税的荷兰三级议会,能够将利率定得很低,从而降低偿债额,这是很恰当的。这一体制被阿姆斯特丹城的金融活动极大地加强了,它很快就使联合省获得了清算债券、贴现和提供贷款的国际声誉。这就自然而然地造成了一种格局和一种气氛,在这种格局内有固定利息的长期国家贷款便被视为家常便饭一类的事情。阿姆斯特丹成功地成为荷兰剩余资本的中心,不久它就可以向外国的公司投资了,最重要的,是它可以向外国政府认购各式各样的债券,特别是在战争期间。

The impact of these activities upon the economy of the United Provinces need not be examined here, although it is clear that Amsterdam would not have become the financial capital of the continent had it not been supported by a flourishing commercial and productive base in the first place. Furthermore, the very long-term consequence was probably disadvantageous, since the steady returns from government loans turned the United Provinces more and more away from a manufacturing economy and into a rentier economy, whose bankers were somewhat disinclined to risk capital in large-scale industrial ventures by the late eighteenth century; while the ease with which loans could be raised eventually saddled the Dutch government with an enormous burden of debt, paid for by excise duties which increased both wages and prices to uncompetitive levels. 8

这里没有必要研究这些活动对联合省经济的影响,虽然那是明摆着的。如果首先没有一个繁荣的商业和生产基础作为支柱,阿姆斯特丹就不会成为大陆的金融中心。此外,应该看到远期的影响也许是不利的,因为源源不断的政府贷款的收益使联合省的经济越来越脱离生产性经济而变成一种高利贷式的经济。它的银行家们不大情愿冒风险将资金投入18世纪末大规模的工业建设项目。轻易即可筹借贷款最终使荷兰政府背上巨大的债务包袱,而靠消费税来偿付又使其工资和物价上涨,结果使荷兰商品失去竞争力。

What is more important for the purposes of our argument is that in subscribing to foreign government loans, the Dutch were much less concerned about the religion or ideology of their clients than about their financial stability and reliability. Accordingly, the terms set for loans to European powers like Russia, Spain, Austria, Poland, and Sweden can be seen as a measure of their respective economic potential, the collateral they offered to the bankers, their record in repaying interest and premiums, and ultimately their prospects of emerging successfully from a Great Power war. Thus, the plummeting of Polish governmental stock in the late eighteenth century and, conversely, the remarkable—and frequently overlooked— strength of Austria’s credit for decade after decade mirrored the relative durability of those states. 9

对我们所讨论的目的更为重要的,倒是荷兰在认购外国政府债券时,对他们顾客的宗教信仰和意识形态满不在乎,更关心的倒是它们财政上的稳定性和可靠性。因此,可以把荷兰给俄国、西班牙、奥地利、波兰和瑞典等欧洲列国所定的贷款条件视为一种尺度,用它来评定各国经济潜力、它们给银行家们提供的抵押、它们偿付利息和贴水的记录、最后是它们在群雄混战中取胜的前景。这样,波兰政府债券在18世纪末的暴跌,以及与之相反的奥地利几十年来常被忽视的非同一般的资信能力,就反映出这些国家不同的耐久力。

But the best example of this critical relationship between financial strength and power politics concerns the two greatest rivals of this period, Britain and France. Since the result of their conflict affected the entire European balance, it is worth examining their experiences at some length. The older notion that eighteenthcentury Great Britain exhibited adamantine and inexorably growing commercial and industrial strength, unshakable fiscal credit, and a flexible, upwardly mobile social structure—as compared with an ancien régime France founded upon the precarious sands of military hubris, economic backwardness, and a rigid class system—seems no longer tenable. In some ways, the French taxation system was less regressive than the British. In some ways, too, France’s economy in the eighteenth century was showing signs of movement toward “takeoff” into an industrial revolution, even though it had only limited stocks of such a critical item as coal. Its armaments production was considerable, and it possessed many skilled artisans and some impressive entrepreneurs. 10 With its far larger population and more extensive agriculture, France was much wealthier than its island neighbor; the revenues of its government and the size of its army dwarfed those of any western European rival; and its dirigiste regime, as compared with the party-based politics of Westminster, seemed to give it a greater coherence and predictability. In consequence, eighteenth-century Britons were much more aware of their own country’s relative weaknesses than its strengths when they gazed across the Channel.

但是,财政实力和强权政治之间这种至关重要的关系的典型例子,要算这一时期两个最大的冤家对头英国和法国。由于他们之间冲突的结局影响着整个欧洲的均势,所以值得对他们的经历进行深入的探讨。有一种观点认为,18世纪的大不列颠显示了坚强和势不可摧的商业与工业力量的增长,显示出不可动摇的财政信誉以及一个可变的、向上流动的社会结构,与之比较起来,旧制度的法国则是建立在穷兵黩武、经济落后和等级制度森严的一盘散沙之上,这种陈旧的观点看来是站不住脚的。在某些方面,法国赋税制度比起英国来,税率递减不那么严重。另一方面,尽管它在一些重要项目上落后,如煤的蕴藏量十分有限,但18世纪时法国的经济仍呈现出向工业革命“起飞”的现象。它的军火生产是十分可观的,它还拥有许多熟练工匠和一些引人注目的企业家。比起它的海岛邻国来,它有更多的人口和更大规模的农业,因而更富足。法国政府的收入和军队的数量使任何一个西欧对手都相形见绌。同威斯敏斯特的政党政治相比,其统治经济制度似乎赋予其更大的凝聚力和可预见性。因此,18世纪的英国人在注视海峡对岸时,更清醒地意识到自己国家的相对劣势而不是实力。

For all this, the English system possessed key advantages in the financial realm which enhanced the country’s power in wartime and buttressed its political stability and economic growth in peacetime. While it is true that its general taxation system was more regressive than that of France—that is, it relied far more upon indirect than direct taxes—particular features seem to have made it much less resented by the public. For example, there was in Britain nothing like the vast array of French tax farmers, collectors, and other middlemen; many of the British duties were “invisible” (the excise duty on a few basic products), or appeared to hurt the foreigner (customs); there were no internal tolls, which so irritated French merchants and were a disincentive to domestic commerce; the British land tax—the chief direct tax for so much of the eighteenth century—allowed for no privileged exceptions and was also “invisible” to the greater part of society; and these various taxes were discussed and then authorized by an elective assembly, which for all its defects appeared more representative than the ancien régime in France. When one adds to this the important point that per capita income was already somewhat higher in Britain than in France even by 1700, it is not altogether surprising that the population of the island state was willing and able to pay proportionately larger taxes. Finally, it is possible to argue—although more difficult to prove statistically— that the comparatively light burden of direct taxation in Britain not only increased the propensity to save among the better-off in society (and thus allowed the accumulation of investment capital during years of peace), but also produced a vast reserve of taxable wealth in wartime, when higher land taxes and, in 1799, direct income tax were introduced to meet the national emergency. Thus, by the period of the Napoleonic War, despite a population less than half that of France, Britain was for the first time ever raising more revenue from taxes each year in absolute terms than its larger neighbor. 11

尽管如此,英国体制在财政领域还是拥有关键的优势。这在战时增强了它的国力,在平时加强了它政治的稳定和促进了经济的增长。不错,虽然它总的赋税制度比法国来说税率递减得更大,这就是说更加依赖于间接税而不是直接税,但由于这种独一无二的特色似乎使公众对它的不满不那么强烈。比如说,在英国没有法国那样大批的包税人、收税官和其他中间人。英国的许多税是“无形的”(对几种基本产品的消费税),或看上去只损害外国人的利益(关税)。它国内没有通行税。法国的商人们对国内的通行税深恶痛绝,它阻碍了国内商业的发展。英国的土地税在18世纪是主要的直接税,不允许有特殊的豁免,同时对社会的大部分人来说也是“无形的”。这些不同形式的捐税由选举出来的议会加以讨论,然后授权征收。尽管议会有种种缺陷,看来还是要比法国的旧制度更具有代表性。早在1700年前英国的人均收入就已高出法国,当注意到这一要点时,这个岛国的居民情愿并且能够相应地多交纳一些捐税也就不足为奇了。最后,虽然很难用统计数字来证明,人们却可以论证英国较轻的直接税负担不仅增加了社会中小康人家的储蓄倾向(这样在平时就积累起投资的资金),而且也为战时积聚了可征税的大量财富,战时英国就开征了更高额的土地税和在1799年开征直接税,以应付国家紧急需要。这样,到了拿破仑战争时期,尽管人口还不到法国的一半,英国每年从赋税筹集的收入第一次超过了比它大的邻国。

Yet however remarkable that achievement, it is eclipsed in importance by the even more significant difference between the British and French systems of public credit. For the fact was that during most of the eighteenth-century conflicts, almost three-quarters of the extra finance raised to support the additional wartime expenditures came from loans. Here, more than anywhere else, the British advantages were decisive. The first was the evolution of an institutional framework which permitted the raising of long-term loans in an efficient fashion and simultaneously arranged for the regular repayment of the interest on (and principal of) the debts accrued. The creation of the Bank of England in 1694 (at first as a wartime expedient) and the slightly later regularization of the national debt on the one hand and the flourishing of the stock exchange and growth of the “country banks” on the other boosted the supply of money available to both governments and businessmen. This growth of paper money in various forms without severe inflation or the loss of credit brought many advantages in an age starved of coin. Yet the “financial revolution” itself would scarcely have succeeded had not the obligations of the state been guaranteed by successive Parliaments with their powers to raise additional taxes; had not the ministries—from Walpole to the younger Pitt—worked hard to convince their bankers in particular and the public in general that they, too, were actuated by the principles of financial rectitude and “economical” government; and had not the steady and in some trades remarkable expansion of commerce and industry provided concomitant increases in revenue from customs and excise. Even the onset of war did not check such increases, provided the Royal Navy protected the nation’s overseas trade while throttling that of its foes. It was upon these solid foundations that Britain’s “credit” rested, despite early uncertainties, considerable political opposition, and a financial near-disaster like the collapse of the famous South Seas Bubble of 1720. “Despite all defects in the handling of English public finance,” its historian has noted, “for the rest of the century it remained more honest, as well as more efficient, than that of any other in Europe. ”12

然而,不论上述成就是多么了不起,其重要性比起英法两国在公共信贷制度上更重大的差别来,也就黯然失色了。事实上,在18世纪绝大部分战争时期,在为额外的战争开支所另外筹措的款项中,几乎有3/4来自借款。英国在这方面比在其他任何方面都更占有决定性的优势。首先是体制性结构的演进容许高效率地筹措到长期贷款,而同时负责定期偿付由此产生的债款利息(及本金)。1694年创建的英格兰银行(最初作为战争中的应急措施)和稍后对国债的调整,以及债券交易的兴旺和“乡村银行”的发展,这两个方面为政府和商人获得资金开辟了财源。在一个硬币匮乏的时代,形形色色纸币的发行在没有引发通货膨胀和导致信誉下降的情况下,带来了极大的好处。但是,如果国家的证券没有历届议会及其征收附加税的权力作担保;如果没有从沃尔波尔到小皮特的历届政府殚精竭虑使银行家们和公众相信他们毫无例外地也是按照金融准则行事,是“节俭”的政府;如果没有商业和工业的持续发展和在某些方面突飞猛进的发展提供了关税和消费税收入的同步增长的话,那么这场“金融革命”就很难成功。只要皇家海军保护着英国的海外贸易并扼制住敌人,即使战争也未能阻止这种增长。英国的“信誉”就是建立在这种牢固的基础上的,尽管有早期的动荡,政治上遭到激烈的反对,以及近乎金融灾难的1720年“南海泡沫”的破产。英国的历史学家们曾评论道,“尽管在处理英国公共财政时弊病百出,但是在该世纪后一段时期,英国比起任何其他欧洲国家来说,都更加守信誉,更加有效率。”

The result of all this was not only that interest rates steadily dropped,* but also that British government stock was increasingly attractive to foreign, and particularly Dutch, investors. Regular dealings in these securities on the Amsterdam market thus became an important part of the nexus of Anglo-Dutch commercial and financial relationships, with important effects upon the economies of both countries. 13 In power-political terms, its value lay in the way in which the resources of the United Provinces repeatedly came to the aid of the British war effort, even when the Dutch alliance in the struggle against France had been replaced by an uneasy neutrality. Only at the time of the American Revolutionary War—significantly, the one conflict in which British military, naval, diplomatic, and trading weaknesses were most evident, and therefore its credit-worthiness was the lowest—did the flow of Dutch funds tend to dry up, despite the higher interest rates which London was prepared to offer. By 1780, however, when the Dutch entered the war on France’s side, the British government found that the strength of its own economy and the availability of domestic capital were such that its loans could be almost completely taken up by domestic investors.

其结果不仅令利率稳步下降,[2]而且使英国政府债券对外国投资者,特别是对荷兰人产生了愈来愈大的吸引力。在阿姆斯特丹金融市场上进行定期的英国政府债券交易,成为联系英荷两国贸易和金融关系的重要部分,并对两国的经济都带来巨大影响。在“强权政治”的条件下,它的价值在于:尽管反对法国的盟国荷兰已变成左右为难的中立国,联合省的资金却能屡次为英国进行战争输血打气。值得注意的是,北美独立战争是英国陆军、海军、外交和贸易的弱点都暴露无遗的一次冲突,因而它的资信能力降到了谷底。只有在这次战争时期,荷兰资金的流入才趋于枯竭,即使伦敦准备提供更高的利率也无济于事了。可是到了1780年,当荷兰加入法国一方对英作战时,英国政府发现它自己的经济实力和国内可供使用的资金与往昔大不相同,国内投资者几乎可以完全提供它所需要的借款了。

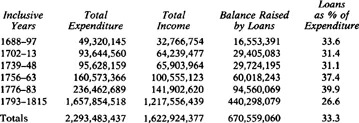

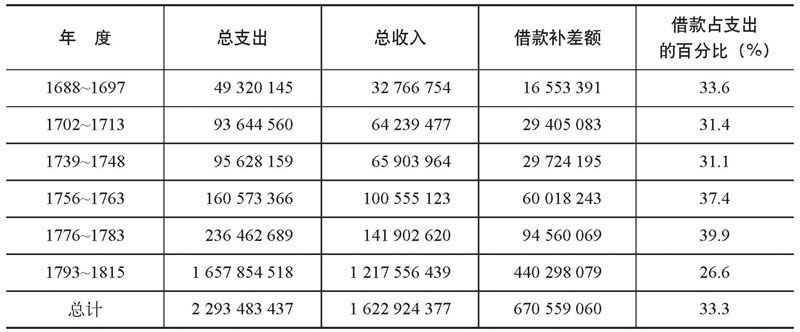

The sheer dimensions—and ultimate success—of Britain’s capacity to raise war loans can be summarized as in Table 2.

英国举借战债能力的绝对数额及其最终成绩可归纳为表2:

Table 2. British Wartime Expenditure and Revenue, 1688–1815

表2.英国战争时期的支出和收入(1688—1875年) (单位:英镑)

And the strategical consequence of these figures was that the country was thereby enabled “to spend on war out of all proportion to its tax revenue, and thus to throw into the struggle with France and its allies the decisive margin of ships and men without which the resources previously committed might have been committed in vain. ”14 Although many British commentators throughout the eighteenth century trembled at the sheer size of the national debt and its possible consequences, the fact remained that (in Bishop Berkeley’s words) credit was “the principal advantage that England hath over France. ” Finally, the great growth in state expenditures and the enormous, sustained demand which Admiralty contracts in particular created for iron, wood, cloth, and other wares produced a “feedback loop” which assisted British industrial production and stimulated the series of technological breakthroughs that gave the country yet another advantage over the French. 15

这些数字的战略意义在于英国能够“把大大超过其税务收入的钱财用于战争,这样一来它就把具有决定性优势的舰只和兵力投入同法国及其同盟国的战争,而没有这种优势,它先前所投入的人力物力便都会付诸东流”。尽管许多英国评论家在整个18世纪一提到英国债务的庞大数额及其可能带来的后果,就谈虎色变,但事实上(用主教柏克利的话来说)信贷是“英国对法国的首要优势”。最后,国家支出的猛烈增长,特别是海军部订货造成的对生铁、木材、布匹和其他物资的巨大而持续的需求,造成一个“反馈环”,促进了英国的工业生产,刺激了技术上一系列的突破。这又使英国增加了一项对法国的优势。

Why the French failed to match these British habits is now easy to see. 16 There was, to begin with, no proper system of public finance. From the Middle Ages onward, the French monarchy’s financial operations had been “managed” by a cluster of bodies—municipal governments, the clergy, provincial estates, and, increasingly, tax farmers—which collected the revenues and supervised the monopolies of the crown in return for a portion of the proceeds, and which simultaneously advanced monies to the French government—at handsome rates of interest—on the expected income from these operations. The venality of this system applied not only to the farmers general who gathered in the tobacco and salt dues; it was also true of that hierarchy of parish collectors, district receivers, and regional receivers general responsible for direct taxes like the taille. Each of them took his “cut” before passing the monies on to a higher level; each of them also received 5 percent interest on the price he had paid for office in the first place; and many of the more senior officials were charged with paying out sums directly to government contractors or as wages, without first handing their takings in to the royal treasury. These men, too, loaned funds—at interest—to the crown.

为什么法国未能效法英国的这些习惯做法,现在看来是显而易见的。首先,法国没有一个合适的公共财政体系。从中世纪以来,法兰西王国的财政活动被一小撮人所“把持”,被地方政府、僧侣、地方显贵以及越来越多的包税人把持。他们为国王征收捐税,督办王室专卖,作为回报,他们从中获得一部分收益,并同时以很高的利率贷款给法国政府,从中获得预期的收入。在这种制度下,不仅征收烟草税和盐税的包税商贪污受贿,就是那些征收人头税之类直接税的教区收税员、地方收税官和地区收税官也都是假公济私。他们每一个人在将钱交给上一级机关之前,都截留下自己的“折扣”,每个人还获取当初为购买官职所付代价的5%的利息。更有许多高官显贵被控告在将其征收的钱款上交王室财库前,直接将一部分钱付给政府承包商或作为他们的佣金。这些人也向国王放款取利。

Such a lax and haphazard organization was inherently corrupt, and much of the taxpayers’ monies ended in private hands. On occasions, especially after wars, investigations would be launched against financiers, many of whom were induced to pay “compensations” or accept lower interest rates; but such actions were mere gestures. “The real culprit,” one historian has argued, “was the system itself. ”17 The second consequence of this inefficiency was that at least until Necker’s reforms of the 1770s, there existed no overall sense of national accounting; annual tallies of revenue and expenditure, and the problem of deficits, were rarely thought to be of significance. Provided the monarchy could raise funds for the immediate needs of the military and the court, the steady escalation of the national debt was of little import.

这样一个松散、随意凑合的机构从骨子里就是腐败的,纳税人的许多钱财结果都落入私人的腰包。有时,特别是在战争结束之后,也发起对这些理财的人进行一番清查,致使他们中的许多人支付“赔偿”或接受低一些的利率,但这样的举动仅仅是姿态而已。一位历史学家争辩道,“真正的病根在于这个制度本身。”这种低效率的第二个后果是,至少到18世纪70年代内克改革之前,法国人都没有一个全国性账目核算的总体意识,没有支出与收入的年度账目,对财政赤字也认为无关紧要。只要能为其军队和宫廷的眼前急需搞到钱,国债的步步上升对国王来说是无足轻重的。

While a similar sort of irresponsibility had earlier been shown by the Stuarts, the fact was that by the eighteenth century Britain had evolved a parliamentarycontrolled form of public finance which gave it numerous advantages in the duel for primacy. Not the least of these seems to have been that while the rise in government spending and in the national debt did not hurt (and may indeed have boosted) British investment in commerce and industry, the prevailing conditions in France seem to have encouraged those with surplus capital to purchase an office or an annuity rather than to invest in business. On some occasions, it was true, there were attempts to provide France with a national bank, so that the debt could be properly managed and cheap credit provided; but such schemes were always resisted by those with an interest in the existing system. The French government’s financial policy, if indeed it deserves that name, was therefore always a hand-to-mouth affair.

尽管早先的斯图亚特王朝也表现出与此类似的漫不经心,但到18世纪前英国就实行了一套由议会控制国家财政的体系,使英国在争霸斗争中占有很大优势。英国政府的开支和国债增长并没有损害(也许实际是促进了)英国在商业和工业领域的投资,而法国在多数情况下似乎是鼓励那些有剩余资金的人去收买官职或年金,而不是鼓励他们将钱投到生产中去,这种情况也是一个重要因素。有时也的确有人试图为法国建立一个国家银行,以便有效地管理债务,并提供低息贷款。但这些设想总是遭到那些在现存制度中享有既得利益的人的反对。因而法国的财政政策,如果它真配这个称呼的话,始终是顾头不顾尾。

France’s commercial development also suffered in a number of ways. It is interesting to note, for example, the disadvantages under which a French port like La Rochelle operated compared with Liverpool or Glasgow. All three were poised to exploit the booming “Atlantic economy” of the eighteenth century, and La Rochelle was particularly well sited for the triangular trade to West Africa and the West Indies. Alas for such mercantile aspirations, the French port suffered from the repeated depredations of the crown, “insatiable in its fiscal demands, unrelenting in its search for new and larger sources of revenue. ” A vast array of “heavy, inequitable and arbitrarily levied direct and indirect taxes on commerce” retarded economic growth; the sale of offices diverted local capital from investment in trade, and the fees levied by those venal officeholders intensified that trend; monopolistic companies restricted free enterprise. Moreover, although the crown compelled the Rochelais to build a large and expensive arsenal in the 1760s (or have the city’s entire revenues seized!), it did not offer a quid pro quo when wars occurred. Because the French government usually concentrated upon military rather than maritime aims, the frequent conflicts with a superior Royal Navy were a disaster for La Rochelle, which saw its merchant ships seized, its profitable slave trade interrupted, and its overseas markets in Canada and Louisiana eliminated—all at a time when marine insurance rates were rocketing and emergency taxes were being imposed. As a final blow, the French government often felt compelled to allow its overseas colonists to trade with neutral shipping in wartime, but this made those markets ever more difficult to recover when peace was concluded. By comparison, the Atlantic sector of the British economy grew steadily throughout the eighteenth century, and if anything benefited in wartime (despite the attacks of French privateers) from the policies of a government which held that profit and power, trade and dominion, were inseparable. 18

法国商业的发展在许多方面也受到困扰。例如,比较一下法国港口城市拉罗舍尔是在何种不利情况下同英国的利物浦和格拉斯哥竞争的,倒是很有意思。所有三个城市都跃跃欲试,要在18世纪“大西洋经济”腾飞里一显身手,而拉罗舍尔地理位置优良,它坐落在通向西非和西印度群岛的三角贸易线上。可悲的是,虽然商人有这样的热望,法国的拉罗舍尔却不时地遭到国王的掠夺。他“对金钱贪得无厌,冷酷无情地搜刮新的更多的收入来源”。大量“沉重的、不平等的及横征暴敛的直接和间接的商业税”阻碍了经济的发展,卖官鬻爵使地方资金不能用于商业投资,而贪官污吏的巧取豪夺又加剧了这种趋势。专利公司限制了进取精神。更有甚者,尽管国王强迫拉罗舍尔在18世纪60年代建造了一个耗资巨大的大军火库(否则拿走全城的所有收入!),但战争真的来临时,法国却将其置之不用。由于通常法国政府将其目标放在陆上而不是海上,同处于优势的英国皇家海军频繁作战给拉罗舍尔带来灾难性后果。它眼睁睁地看着它的商船被掳掠,赚钱的奴隶贸易被中断,它在加拿大和路易斯安娜的海外市场丧失殆尽。所有这一切还都发生在海上保险费暴涨并开征紧急税的时候。法国政府还常常感到不得不允许其海外殖民者在战时用中立船贸易,这好似致命一击,使得这些市场在和约缔结时更难恢复元气。对比之下,大西洋上的英国经济在整个18世纪都在稳步地发展。如果说有什么在战时(尽管有法国私掠船的袭扰)从掌握权力又获得利润的英国政府的政策中得到好处的话,那就是贸易与海外领地,它们是不可分割的。

The worst consequence of France’s financial immaturity was that in time of war its military and naval effort was eroded, in a number of ways. 19 Because of the inefficiency and unreliability of the system, it took longer to secure the supply of (say) naval stores, while contractors usually needed to charge more than would be the case with the British or Dutch admiralties. Raising large sums in wartime was always more of a problem for the French monarchy, even when it drew increasingly upon Dutch money in the 1770s and 1780s, for its long history of currency revaluations, its partial repudiations of debt, and its other arbitrary actions against the holders of short-term and long-term bills caused bankers to demand—and a desperate French state to agree to—rates of interest far above those charged to the British and many other European governments. * Yet even this willingness to pay over the odds did not permit the Bourbon monarchs to secure the sums which were necessary to sustain an all-out military effort in a lengthy war.

法国财政不健全的最大恶果,是战时它的陆军和海军的浴血奋战在许多方面都成为徒劳了。由于制度的低效率和不可靠性,就需要更多的时间去获得给养,如海军储备,而军火商们往往又比他们同英国或荷兰海军部订合同时开价更高。对法国君主政权来说,在战时筹措大笔资金往往是最头痛的事,尽管到18世纪70到80年代它已经越来越依赖荷兰的资金了。由于它货币币值长期浮动、部分赖债以及它对短期或长期债券持有人的种种蛮横无理的做法,使金融家们对法国要求收取比英国或许多其他欧洲国家都高得多的利息,而借贷无门的法国也只好同意。[3]然而即使法国情愿接受这些苛刻的条件,波旁王朝还是无法筹措到足够的资金去支持它在持久战中的军事行动。

The best illustration of this relative French weakness occurred in the years following the American Revolutionary War. It had hardly been a glorious conflict for the British, who had lost their largest colony and seen their national debt rise to about £220 million; but since those sums had chiefly been borrowed at a mere 3 percent interest, the annual repayments totaled only £7. 33 million. The actual costs of the war to France were considerably smaller; after all, it had entered the conflict at the halfway stage, following Necker’s efforts to balance the budget, and for once it had not needed to deploy a massive army. Nonetheless, the war cost the French government at least a billion livres, virtually all of which was paid by floating loans at rates of interest at least double that available to the British government. In both countries, servicing the debt consumed half the state’s annual expenditures, but after 1783 the British immediately embarked upon a series of measures (the Sinking Fund, a consolidated revenue fund, improved public accounts) in order to stabilize that total and strengthen its credit—the greatest, perhaps, of the younger Pitt’s achievements. On the French side, by contrast, large new loans were floated each year, since “normal” revenues could never match even peacetime expenditures; and with yearly deficits growing, the government’s credit weakened still further.

最能说明法国这种弱点的时期,是在美国独立战争之后的年代。对于英国来说,这不是一场光彩的战争。它丧失了最大的一块殖民地,眼看着国债上升到2.2亿英镑。但由于这些钱主要是以3%的低利率借来的,因而每年偿还借款的总额只有733万英镑。这场战争对法国的实际损耗要少得多。不管怎么说,法国只是到战争进行到了一半时才参加进去,而且还是在内克平衡国家预算的努力之后。同时,这一次法国不必部署一支庞大的陆军。但是,这场战争花费了法国至少10亿列弗尔。几乎所有这些钱都是以英国政府所借贷款至少两倍的利率借来的短期贷款。两国为偿还债务,都耗费了各自国家年支出的一半。但是在1783年之后,英国立即着手采取一系列措施(建立一种统一收入基金“偿债基金”,改善政府账目)以稳定债务总额,加强其资信能力。这大概是小皮特最辉煌的成就,相反,法国方面每年都发行大量新的债券以筹款。这是因为“正常”收入即使在平时也不敷支出,随着赤字年年增长,法国政府的信誉进一步削弱。

The startling statistical consequence was that by the late 1780s France’s national debt may have been almost the same as Britain’s—around £215 million—but the interest payments each year were nearly double, at £14 million. Still worse, the efforts of succeeding finance ministers to raise fresh taxes met with stiffening public resistance. It was, after all, Calonne’s proposed tax reforms, leading to the Assembly of Notables, the moves against the parlements, the suspension of payments by the treasury, and then (for the first since 1614) the calling of the States General in 1789 which triggered off the final collapse of the ancien régime in France. 20 The link between national bankruptcy and revolution was all too clear. In the desperate circumstances which followed, the government issued ever more notes (to the value of 100 million livres in 1789, and 200 million in 1790), a device replaced by the Constituent Assembly’s own expedient of seizing church lands and issuing paper money on their estimated worth. All this led to further inflation, which the 1792 decision for war only exacerbated. And while it is true that later administrative reforms within the treasury itself and the revolutionary regime’s determination to know the true state of affairs steadily produced a unified, bureaucratic, revenuecollecting structure akin to those existing in Britain and elsewhere, the internal convulsions and external overextension that were to last until 1815 caused the French economy to fall even further behind that of its greatest rival.

令人吃惊的统计结果显示,到18世纪80年代末期,法国国债数额显示几乎达到英国的水平,近2.15亿英镑,但它每年要支付的利息差不多是英国的2倍,即1 400万英镑。更糟的是,法国历任财政大臣试图征收新税的努力都遭到公众顽强的抵制。是加隆提出的导致召开显贵会议的赋税改革议案、反对最高法院的动议、国库停止偿付债务以及随后(1614年以来的第一次)于1789年召集的三级会议,终于触发了法国旧制度的最终崩溃。国家失去偿付能力和革命之间的联系是显而易见的。在嗣后的危机年代里,法国政府愈加增发钞票(1789年发行1亿列弗尔,1790年发行2亿列弗尔)。这种手段被制宪会议的应急措施所取代。它没收了教会的地产,按其估计价值发行纸币。所有这一切导致了更严重的通货膨胀,而1792年作出打仗的决定更是雪上加霜。虽然以后国库内部进行的行政改革和革命政权了解真相的决心,的确稳固地建立了一个类似于英国及其他国家的、统一的、官僚化的税务机构。但持续到1815年的国内动乱和过度的对外侵略扩张,导致法国经济越来越远地落到它主要对手的后面。

This problem of raising revenue to pay for current—and previous—wars preoccupied all regimes and their statesmen. Even in peacetime, the upkeep of the armed services consumed 40 or 50 percent of a country’s expenditures; in wartime, it could rise to 80 or even 90 percent of the far larger whole! Whatever their internal constitutions, therefore, autocratic empires, limited monarchies, and bourgeois republics throughout Europe faced the same difficulty. After each bout of fighting (and especially after 1714 and 1763), most countries desperately needed to draw breath, to recover from their economic exhaustion, and to grapple with the internal discontents which war and higher taxation had all too often provoked; but the competitive, egoistic nature of the European states system meant that prolonged peace was unusual and that within another few years preparations were being made for further campaigning. Yet if the financial burdens could hardly be carried by the French, Dutch, and British, the three richest peoples of Europe, how could they be borne by far poorer states?

所有的政府和政治家们都被如何增加税收,以支付正在进行的和以前进行的战争所困扰。即使在和平时期,维持其军队也要耗费国家财政支出的40%—50%,而在战时,国家支出总额远远超过平时,军费要占总支出的80%甚至90%。不论各国政体如何,不论是君主独裁帝国、有限君主政体,还是资产阶级共和国,整个欧洲无一例外都面临着同样的难题。在每一轮战争之后(特别是在1714年和1763年以后),大多数国家都极度渴望喘息一下,从精疲力竭的经济中恢复过来,腾出手来对付因战争和苛捐杂税常常导致的国内不满。但是,欧洲列国制度的竞争性和利己主义本性意味着长期的和平是稀有的。因此,在几年之内,各国又在为新的大战作准备。但是如果连欧洲最富强的三个大国,法国、荷兰和英国都不堪这样的财政重负,更穷的国家又怎么能担负得起呢?

The simple answer to this question was that they couldn’t. Even Frederick the Great’s Prussia, which drew much of its revenues from the extensive, wellhusbanded royal domains and monopolies, could not meet the vast demands of the war of the Austrian Succession and Seven Years War without recourse to three “extraordinary” sources of income: profits from debasement of the coinage; plunder from neighboring states such as Saxony and Mecklenburg; and, after 1757, considerable subsidies from its richer ally, Britain. For the less efficient and more decentralized Habsburg Empire, the problems of paying for war were immense; but it is difficult to believe that the situation was any better in Russia or in Spain, where the prospects for raising monies—other than by further squeezes upon the peasantry and the underdeveloped middle classes—were not promising. With so many orders (e. g. , Hungarian nobility, Spanish clergy) claiming exemptions under the anciennes régimes, even the invention of elaborate indirect taxes, debasements of the currency, and the printing of paper money were hardly sufficient to maintain the elaborate armies and courts in peacetime; and while the onset of war led to extraordinary fiscal measures for the national emergency, it also meant that increasing reliance had to be placed upon the western European money markets or, better still, direct subsidies from London, Amsterdam, or Paris which could then be used to buy mercenaries and supplies. Pas d’argent, pas de Suisses may have been a slogan for Renaissance princes, but it was still an unavoidable fact of life even in Frederician and Napoleonic times. 21

这一问题的答案是简单的——他们负担不起。腓特烈大帝的普鲁士,虽然能够从王室领地和专卖公司中取得很大一部分收入,但如果不靠三种“特殊”的收入来源,即掠夺萨克森和梅克伦堡这样的邻国,以及在1757年后从它富裕的盟邦英国那里得到津贴,也应付不了奥地利王位争夺战和七年战争的巨大开销。对于效率不高、权力分散的哈布斯堡帝国来说,支付战争费用更是一个大问题。很难相信在俄国和西班牙情况会好多少。对这两个国家来说,除了进一步压榨农民和贫穷的中产阶级外,开源增收是没什么指望的。由于旧制度下的许多阶层(例如匈牙利的贵族,西班牙的僧侣)都要求免税,即使发明了巧妙的间接税、货币贬值和印刷纸币,也还是难以在和平时期供养分工复杂的军队和宫廷。所以战争的爆发就迫使各国采取特殊的财政措施以应付国家的紧急需要。这意味着他们不得不增加对西欧金融市场的依赖,或者是更加依赖伦敦、阿姆斯特丹或巴黎的直接接济。这些钱便可用于收买雇佣兵和军需品。“没有钱,就没有瑞士雇佣兵”可能曾是文艺复兴时期王公们的一个口号,但直到腓特烈和拿破仑时代,这仍是生活中无法回避的基本现实。

This is not to say, however, that the financial element always determined the fate of nations in these eighteenth-century wars. Amsterdam was for much of this period the greatest financial center of the world, yet that alone could not prevent the United Provinces’ demise as a leading Power; conversely, Russia was economically backward and its government relatively starved of capital, yet the country’s influence and might in European affairs grew steadily. To explain that seeming discrepancy, it is necessary to give equal attention to the second important conditioning factor, the influence of geography upon national strategy.

然而,这并不等于说,决定列国在18世纪各场战争中命运的总是财政因素。在这一时期的大部分时间里,阿姆斯特丹是世界上最大的金融中心,但仅此一点并不能阻止联合省从一个主要大国的地位跌落下来。相反,俄国虽然经济落后,政府资金相对匮乏,但该国在欧洲事务中发挥的影响和实力却与日俱增。要解释这种表面上的矛盾,就有必要给予第二个重要的制约因素——地理对国家战略的影响——给予同样的重视。