Geopolitics

二、地缘政治

Because of the inherently competitive nature of European power politics and the volatility of alliance relationships throughout the eighteenth century, rival states often encountered remarkably different circumstances—and sometimes extreme variations of fortune—from one major conflict to the next. Secret treaties and “diplomatic revolutions” produced changing conglomerations of powers, and in consequence fairly frequent shifts in the European equilibrium, both military and naval. While this naturally caused great reliance to be placed upon the expertise of a nation’s diplomats, not to mention the efficiency of its armed forces, it also pointed to the significance of the geographical factor. What is meant by that term here is not merely such elements as a country’s climate, raw materials, fertility of agriculture, and access to trade routes—important though they all were to its overall prosperity —but rather the critical issue of strategical location during these multilateral wars. Was a particular nation able to concentrate its energies upon one front, or did it have to fight on several? Did it share common borders with weak states, or powerful ones? Was it chiefly a land power, a sea power, or a hybrid—and what advantages and disadvantages did that bring? Could it easily pull out of a great war in Central Europe if it wished to? Could it secure additional resources from overseas?

由于欧洲列强政治固有的竞争性,以及贯穿于整个18世纪各国之间同盟关系的不断变动,敌对国家常常从一场冲突到另一场冲突时遇到截然不同的情况,有时是极为变幻莫测的命运。秘密条约和“外交革命”造成列强之间组合的不断变化。由此引起欧洲均势、陆军和海军两个方面的力量对比的动荡变化。这就自然而然地使各国极大地依赖其外交家的聪明才智,更不用说武装部队的效能了。同时它还表明了地理因素的重要性。这里所说的地理因素不仅包括一个国家的气候、原料、农业生产力、可以利用的商路等因素,尽管这些因素对一国的全面繁荣强盛是很重要的,更重要的是指每个国家在这些多边战争中所处的战略位置这样一个关键问题。某一特定国家是否能将其全部力量集中投入到一条战线,还是不得不在几条战线上同时作战?它是同弱小国家接壤呢,还是同强国接壤?它主要是陆上大国呢,还是海上大国?或者两者兼而有之?这一切又给它带来何种有利因素,何种不利因素?如果它想退出战争的话,能否轻易地从一场中欧大战中脱身?它能否从海外获得额外的资源?

The fate of the United Provinces in this period provides a good example of the influences of geography upon politics. In the early seventeenth century it possessed many of the domestic ingredients for national growth—a flourishing economy, social stability, a well-trained army, and a powerful navy; and it had not then seemed disadvantaged by geography. On the contrary, its river network provided a barrier (at least to some extent) against Spanish forces, and its North Sea position gave it easy access to the rich herring fisheries. But a century later, the Dutch were struggling to hold their own against a number of rivals. The adoption of mercantilist policies by Cromwell’s England and Colbert’s France hurt Dutch commerce and shipping. For all the tactical brilliance of commanders like Tromp and de Ruyter, Dutch merchantmen in the naval wars against England had either to run the gauntlet of the Channel route or to take the longer and stormier route around Scotland, which (like their herring fisheries) was still open to attack in the North Sea; the prevailing westerly winds gave the battle advantage to the English admirals; and the shallow waters off Holland restricted the draft—and ultimately the size and power—of the Dutch warships. 22 In the same way as its trade with the Americas and Indies became increasingly exposed to the workings of British sea power, so, too, was its Baltic entrep?t commerce—one of the very foundations of its early prosperity—eroded by the Swedes and other local rivals. Although the Dutch might temporarily reassert themselves by the dispatch of a large battle fleet to a threatened point, there was no way in which they could permanently preserve their extended and vulnerable interests in distant seas.

联合省在这个时代的国运兴衰是说明地理因素对政治产生影响的一个极好的例子。在17世纪初期,它具备了国家发展的许多要素,诸如国内经济繁荣,社会稳定,陆军训练有素,海军实力雄厚,而它的地理位置当时也看不出对它有何不利之处。恰恰相反,纵横交错的河网为它对付西班牙提供了天然屏障(至少是在一定程度上),而濒临北海,又为它利用富饶的鲱鱼资源提供了通路。但一个世纪之后,荷兰面对几个强敌,却在保卫自己的困境中挣扎。自从克伦威尔的英国和柯尔培尔的法国采取重商主义政策后,荷兰的商业和航运就受到了打击。不论特隆普和德·吕泰尔那样的指挥官战术指挥才能多么杰出,在对英国的海战中,荷兰商人或者不得不闯过两翼受敌的英吉利海峡,或者不得不兜个大圈子,绕过波涛汹涌的苏格兰,而这条路线(像他们捕捞鲱鱼一样),在北海仍然容易受到敌人的攻击。盛行的西风助了英国海军将领们一臂之力,而荷兰沿岸的浅海,限制了荷兰战舰的吃水深度,从而限制了战舰的吨位和火力。同样,它同美洲及印度的贸易也越来越暴露在不列颠海军的炮口之下。它在波罗的海的转口贸易,曾是它早期崛起的支柱之一,也一样被瑞典人和沿岸的其他对手所削弱。尽管荷兰可以暂时派一支庞大的舰队前往受到威胁的某地重振雄风,但它对长久维持远海的广泛而脆弱的利益还是束手无策。

This dilemma was made worse by Dutch vulnerability to the landward threat from Louis XIV’s France from the late 1660s onwards. Since this danger was even greater than that posed by Spain a century earlier, the Dutch were forced to expand their own army (it was 93,000 strong by 1693) and to devote ever more resources to garrisoning the southern border fortresses. This drain upon Dutch energies was twofold: it diverted vast amounts of money into military expenditures, producing the upward spiral in war debts, interest repayments, increased excise duties, and high wages that undercut the nation’s commercial competitiveness in the long term; and it caused a severe loss of life during wartime to a population which, at about two million, was curiously static throughout this entire period. Hence the justifiable alarm, during the fierce toe-to-toe battles of the War of Spanish Succession (1702– 1713), at the heavy losses caused by Marlborough’s willingness to launch the Anglo- Dutch armies into bloody frontal assaults against the French. 23

从17世纪60年代起,荷兰在陆上的弱点就暴露在路易十四法国的威胁之下,这使荷兰处境更加艰难。由于这一威胁比一个世纪前西班牙所造成的威胁要大得多,荷兰被迫扩充自己的陆军(到1693年实力为93 000人),并将更多的人力物力投入到防守南部边界的要塞中去。这从两方面耗尽了荷兰的力量:它使大量的金钱用于军事开支,从而造成战债和利息支出的螺旋式上升;提高消费税和工资,削弱了本国商业的长远竞争力。荷兰在战争时期遭受大量的人员损失,而在整个这一时期,荷兰人口反常地停滞在200万人上。由于这个缘故,在西班牙王位继承战争(1702—1713年)期间接踵而至的战斗中,当马尔伯勒执意派遣英荷联军对法国的正面防线发动浴血进攻而造成人员的惨重损失时,荷兰人理所当然地感到惊恐。

The English alliance which William III had cemented in 1689 was simultaneously the saving of the United Provinces and a substantial contributory factor in its decline as an independent great power—in rather the same way in which, over two hundred years later, Lend-Lease and the United States alliance would both rescue and help undermine a British Empire which was fighting for survival under Marlborough’s distant relative Winston Churchill. The inadequacy of Dutch resources in the various wars against France between 1688 and 1748 meant that they needed to concentrate about three-quarters of defense expenditures upon the military, thus neglecting their fleet—whereas the British assumed an increasing share of the maritime and colonial campaigns, and of the commercial benefits therefrom. As London and Bristol merchants flourished, so, to put it crudely, Amsterdam traders suffered. This was exacerbated by the frequent British efforts to prevent all trade with France in wartime, in contrast to the Dutch wish to maintain such profitable links—a reflection of how much more involved with (and therefore dependent upon) external commerce and finance the United Provinces were throughout this period, whereas the British economy was still relatively selfsufficient. Even when, by the Seven Years War, the United Provinces had escaped into neutrality, it availed them little, for an overweening Royal Navy, refusing to accept the doctrine of “free ships, free goods,” was determined to block France’s overseas commerce from being carried in neutral bottoms. 24 The Anglo-Dutch diplomatic quarrel of 1758–1759 over this question was repeated during the early years of the American Revolutionary War and eventually led to open hostilities after 1780, which did nothing to help the seaborne commerce of either Britain or the United Provinces. By the time of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic struggles, the Dutch found themselves ground ever more between Britain and France, suffering from widespread debt repudiations, affected by domestic fissures, and losing colonies and overseas trade in a global contest which they could neither avoid nor take advantage of. In such circumstances, financial expertise and reliance upon “surplus capital” was simply not enough. 25

1689年由威廉三世所缔造的英荷联盟同时起了双重作用,它既挽救了联合省,同时又是促成它作为一个独立大国衰落的重要因素。这同两百余年后的“租借法”和英美同盟如出一辙。它们既挽救又削弱了当时在马尔伯勒的后裔温斯顿·丘吉尔领导下为生存而战的不列颠帝国。在1688年和1748年之间对法国的数次战争中,荷兰都感到资源不足。这对它意味着必须把防务开支的3/4用于陆军,因而忽视了舰队。而英国却在海上和殖民活动中占了越来越多的份额,并从中捞取越来越多的商业利益。简言之,当伦敦和布里斯托尔的商人们兴旺发达起来时,阿姆斯特丹的商人们却倒了大霉。由于英国不顾荷兰要保持同法国商业联系的意愿,在战争期间经常竭力阻止同法国的一切贸易往来,就使荷兰商人损失更大。这也反映出联合省在整个这一时期是多么深地卷入(因而更加依赖)对外贸易和金融往来。而英国的经济相对来说仍然是自给自足的。即使到七年战争时期联合省宣布保持中立,也没有帮它多少忙。因为骄横的皇家海军拒绝承认“自由商船,自由货物”的原则,决意要封锁法国,阻止其用中立国船只进行海外贸易。英荷两国在1759年间就这一问题所发生的外交纠纷,在美国独立战争初期又多次发生,并最终导致两国1780年以后的公开冲突。这些冲突丝毫无助于英国或荷兰的海上贸易。直到法国大革命和拿破仑战争,荷兰人发现他们自己愈加陷进英法两国的夹缝中间,受到普遍赖债的损失,受国内分裂的影响,同时,在它既无法避免又得不到任何好处的世界竞争中,丢失了自己的殖民地和海外贸易。在这种情况下,即使有金融上的精明强干以及对“剩余资本”的依赖也是无力回天的。

In much the same way, albeit on a grander scale, France also suffered from being a hybrid power during the eighteenth century, with its energies diverted between continental aims on the one hand and maritime and colonial ambitions on the other. In the early part of Louis XIV’s reign, this strategical ambivalence was not so marked. France’s strength rested firmly upon indigenous materials: its large and relatively homogeneous territory, its agricultural self-sufficiency, and its population of about twenty million, which permitted Louis XIV to increase his army from 30,000 in 1659 to 97,000 in 1666 to a colossal 350,000 by 1710. 26 The Sun King’s foreign-policy aims, too, were land-based and traditional: to erode still further the Habsburg positions, by moves in the south against Spain and in the east and north against that vulnerable string of Spanish-Habsburg and German territories Franche Comté, Lorraine, Alsace, Luxembourg, and the southern Netherlands.

与此相类似,法国在更大程度上由于它是海陆混合型国家而在18世纪吃尽了苦头。它的力量一方面要用于大陆上的雄心壮志,另一方面要用于海上和进行殖民的勃勃野心。在路易十四统治初期,战略上这种顾此失彼的情况还不是很明显。法国的力量坚固地建立在固有的物质力量上:广袤又比较单一的领土、自给自足的农业以及约2 000万的人口,这允许路易十四把他的大军从1659年的3万人增加到1666年的9.7万人,进而扩充到1710年的35万人。太阳王外交政策的目标也是建立在欧洲大陆传统之上的:通过在南部打击西班牙,向北向东夺取西班牙-哈布斯堡王朝易受攻击的联系地带以及德意志的领土弗朗什-孔戴、洛林、阿尔萨斯、卢森堡和南尼德兰,从而进一步削弱哈布斯堡王朝的地位。

With Spain exhausted, the Austrians distracted by the Turkish threat, and the English at first neutral or friendly, Louis enjoyed two decades of diplomatic success; but then the very hubris of French claims alarmed the other powers.

当时由于西班牙已精疲力竭,奥地利忙于应付来自土耳其的威胁,而英国起初保持着中立或友好,路易十四在外交上得以赢得20年的胜利。但是好景不长,法国贪婪的胃口激起了其他大国的不安。

The chief strategical problem for France was that although massively strong in defensive terms, she was less well placed to carry out a decisive campaign of conquest: in each direction she was hemmed in, partly by geographical barriers, partly by the existing claims and interests of a number of great powers. An attack on the southern (that is, Habsburg-held) Netherlands, for example, involved grinding campaigns through territory riddled with fortresses and waterways, and provoked a response not merely from the Habsburg powers themselves but also from the United Provinces and England. French military efforts into Germany were also troublesome: the border was more easily breached, but the lines of communication were much longer, and once again there was an inevitable coalition to face—the Austrians, the Dutch, the British (especially after the 1714 Hanoverian succession), and then the Prussians. Even when, by the mid-eighteenth century, France was willing to seek out a strong German partner—that is, either Austria or Prussia—the natural consequence of any such alliance was that the other German power went into opposition and, more important, strove to obtain support from Britain and Russia to neutralize French ambitions.

法国战略上的问题在于,尽管它在防守上力量很强大,但它的地理位置不那么有利于进行决定性的对外征服战役:它在各个方向上都受到阻碍,部分是一些大国已有的领土要求和既得利益的妨碍。例如,进攻尼德兰南部(由哈布斯堡王朝占有),就要进行艰苦的战斗通过布满要塞和河流的地区,这不仅要招致哈布斯堡王朝本身的反击,而且会招致联合省和英国的反应。法国进攻德意志领土的道路也是荆棘丛生:虽然可以轻而易举地突破边界防线,但法军的交通线却要长得多,同时还要面对不可避免的敌国同盟,即奥地利人、荷兰人、英国人(特别是从1714年汉诺威选帝侯继承英国王位后),还有普鲁士人的同盟。即使到了18世纪中叶,当法国想要挑选出一个强大的德意志国家奥地利或是普鲁士作盟国时,这一联盟的必然结果便是另一个德意志大国站到法国的对立面,并且更为重要的是,后者将竭尽全力争取英国和俄国的支持,以便挫败法国的企图。

Furthermore, every war against the maritime powers involved a certain division of French energies and attention from the continent, and thus made a successful land campaign less likely. Torn between fighting in Flanders, Germany, and northern Italy on the one hand and in the Channel, West Indies, Lower Canada, and the Indian Ocean on the other, French strategy led repeatedly to a “falling between stools. ” While never willing to make the all-out financial effort necessary to challenge the Royal Navy’s supremacy,* successive French governments allocated funds to the marine which—had France been solely a land power—might have been used to reinforce the army. Only in the war of 1778–1783, by supporting the American rebels in the western hemisphere but abstaining from any moves into Germany, did France manage to humiliate its British foe. In all its other wars, the French never enjoyed the luxury of strategical concentration—and suffered as a result.

不仅如此,法国同海上大国进行的每一场战争,都要把它的力量和注意力从大陆上分散开去,这样就使其在大陆上进行的战争更难取得胜利。一方面要在佛兰德、德意志和意大利北部打仗,另一方面又要在英吉利海峡、西印度群岛、下加拿大和印度洋作战,法国在这两个战略抉择之间摇摆不定,经常导致它“两头落空”。虽然法国历届政府从来也不情愿在财政上做出向英国皇家海军优势挑战所必须的最大努力[4],但还是要拨出一部分资金给海军。如果法国是一个单一的内陆国家,这笔钱原本可以用来加强其陆军的。只有在1778—1783年的战争中,法国支持美国人在西半球的反叛,同时又放弃了对德意志的任何军事行动,法国才得以羞辱它的英国对手。而在其他所有战争中,法国从来没有能够在战略上集中于一点,结果饱受损失。

In sum, the France of the ancien régime remained, by its size and population and wealth, always the greatest of the European states; but it was not big enough or efficiently organized enough to be a “superpower,” and, restricted on land and diverted by sea, it could not prevail against the coalition which its ambitions inevitably aroused. French actions confirmed, rather than upset, the plurality of power in Europe. Only when its national energies were transformed by the Revolution, and then brilliantly deployed by Napoleon, could it impose its ideas upon the continent—for a while. But even there its success was temporary, and no amount of military genius could ensure permanent French control of Germany, Italy, and Spain, let alone of Russia and Britain.

总之,旧制度的法国领土广大,人口众多,资源丰富,一直是欧洲最强大的国家之一。但要成为一个“超级大国”,它的实力又不够充实,管理国家的效率也不够高。它在大陆上受到限制,在海上又被牵制,因而不可能战胜由于它自己的野心必然激起的敌国联盟。法国的所作所为,加强了而不是打乱了欧洲列强的多极体系。只有当大革命改变了它的国力,而后被雄才伟略的拿破仑恰当地动用起来以后,法国才得以让欧洲大陆在一段时间里对它俯首帖耳。但即使如此,它的成功也只是暂时的。任何军事天才都无法保证法国对德意志、意大利、西班牙的永久控制,更不用说俄国和英国了。

France’s geostrategical problem of having to face potential foes on a variety of fronts was not unique, even if that country had made matters worse for itself by a repeated aggressiveness and a chronic lack of direction. The two great German powers of this period—the Habsburg Empire and Brandenburg-Prussia—were also destined by their geographical position to grapple with the same problem. To the Austrian Habsburgs, this was nothing new. The awkwardly shaped conglomeration of territories they ruled (Austria, Bohemia, Silesia, Moravia, Hungary, Milan, Naples, Sicily, and, after 1714, the southern Netherlands—see Map 5) and the position of other powers in relation to those lands required a nightmarish diplomatic and military juggling act merely to retain the inheritance; increasing it demanded either genius or good luck, and probably both.

在几条战线上同时面对几个潜在的劲敌,这个地理战略上的问题并非只困扰着法国。不同的只是因为法国自己反复的侵略和长期没有一个确定的方向,使这个问题更为严重罢了。这一时期的两个德意志大国,哈布斯堡帝国和勃兰登堡-普鲁士也因为其地理位置,注定要处理同样棘手的问题。对于奥地利的哈布斯堡王朝来说,这并非什么新鲜事务。他们管辖的形状极不规则的领土联合体(奥地利、波希米亚、西里西亚、摩拉维亚、匈牙利、米兰、那不勒斯、西西里,以及1714年以后的尼德兰南部,参看地图5),再加上其他强国同这些领土所处的地理位置,都迫使哈布斯堡王室要想保住帝国的遗产,就不得不在外交上和军事上使尽浑身解数。若要扩大这份遗产就需要更多的聪明才智或者还需要吉星高照,也许两者都不可缺少。

Thus, while the various wars against the Turks (1663–1664, 1683–1699, 1716– 1718,1737–1739,1788–1791) showed the Habsburg armies generally enhancing their position in the Balkans, this struggle against a declining Ottoman Empire consumed most of Vienna’s energies in those selected periods. 27 With the Turks at the gates of his imperial capital in 1683, for example, Leopold I was bound to stay neutral toward France despite the provocations of Louis XIV’s “reunions” of Alsace and Luxembourg in that very year. This Austrian ambivalence was somewhat less marked during the Nine Years War (1689–1697) and the subsequent War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1713), since Vienna had by that time become part of a gigantic anti-French alliance; but it never completely disappeared even then. The course of many later eighteenth-century wars seemed still more volatile and unpredictable, both for the defense of general Habsburg interests in Europe and for the specific preservation of those interests within Germany itself following the rise of Prussia. From at least the Prussian seizure of the province of Silesia in 1740 onward, Vienna always had to conduct its foreign and military policies with one eye firmly on Berlin. This in turn made Habsburg diplomacy more elaborate than ever: to check a rising Prussia within Germany, the Austrians needed to call upon the assistance of France in the west and, more frequently, Russia in the east; but France itself was unreliable and needed in turn to be checked by an Anglo-Austrian alliance at times (e. g. , 1744–1748). Furthermore, Russia’s own steady growth was a further cause of concern, particularly when czarist expansionism threatened the Ottoman hold upon Balkan lands desired by Vienna. Finally, when Napoleonic imperialism challenged the independence of all other powers in Europe, the Habsburg Empire had no choice but to join any available grand coalition to contest French hegemony.

这样,虽然同土耳其的几次战争(1663—1664年,1683—1699年,1716—1718年,1737—1739年,1788—1791年),显示出哈布斯堡的军队全面加强了在巴尔干的地位,但同日趋没落的奥斯曼帝国的战争也耗尽了维也纳在这些时期的大部分精力。比如说,当1683年土耳其人兵临帝国首都城下时,利奥波德一世不得不对法国保持中立,虽然就在同一年发生了路易十四“重新合并”阿尔萨斯和卢森堡的挑衅事件。在九年战争(1689—1697年)和稍后的西班牙王位继承战(1702—1713年)时期,由于维也纳在此以前已经成为强大反法联盟的一员,它此时顾此失彼的矛盾才不那么显著。但即使在这一时期,这个矛盾也并未完全消失。哈布斯堡王室对外既要在欧洲保护其总体利益,在普鲁士崛起之后又要在德意志内部特别加以防范。18世纪晚期的许多战争对哈布斯堡王朝来说都更加变幻莫测。至少从1740年普鲁士夺走西里西亚省之后,维也纳在制定其外交和军事政策时总得用一只眼睛牢牢地盯住柏林。这必然使哈布斯堡王朝的外交变得空前复杂:要在德意志内部阻止普鲁士的崛起,奥地利人需要在西方求得法国的援助,并更经常地在东方请求俄国的帮助。但是法国本身也是靠不住的,还时常需要英奥联盟加以钳制(例如1744—1748年间)。此外,俄国的步步崛起也是一个新的麻烦,特别是当沙皇的扩张威胁到立足于巴尔干领土的奥斯曼人的时候,因为维也纳也觊觎着这片土地。最后,当拿破仑帝国的挑衅威胁到欧洲所有其他列强的生存时,哈布斯堡帝国为了同法国霸权作斗争,除了参加任何可以利用的强大同盟以外,别无其他选择。

The coalition war against Louis XIV at the beginning of the eighteenth century and those against Bonaparte at its end probably give us less of an insight into Austrian weakness than do the conflicts in between. The lengthy struggle against Prussia after 1740 was particularly revealing: it demonstrated that for all the military, fiscal, and administrative reforms undertaken in the Habsburg lands in this period, Vienna could not prevail against another, smaller German state which was considerably more efficient in its army, revenue collection, and bureaucracy. Furthermore, it became increasingly clear that the non-German powers, France, Britain, and Russia, desired neither the Austrian elimination of Prussia nor the Prussian elimination of Austria. In the larger European context, the Habsburg Empire had already become a marginal first-class power, and was to remain such until 1918. It certainly did not slip as far down the list as Spain and Sweden, and it avoided the fate which befell Poland; but, because of its decentralized, ethnically diverse, and economically backward condition, it defied attempts by succeeding administrations in Vienna to turn it into the greatest of the European states. Nevertheless, there is a danger in anticipating this decline. As Olwen Hufton observes, “the Austrian Empire’s persistent, to some eyes perverse, refusal conveniently to disintegrate” is a reminder that it possessed hidden strengths. Disasters were often followed by bouts of reform—the rétablissements—which revealed the empire’s very considerable resources even if they also demonstrated the great difficulty Vienna always had in getting its hands upon them. And every historian of Habsburg decline has somehow to explain its remarkably stubborn and, occasionally, very impressive military resistance to the dynamic force of French imperialism for almost fourteen years of the period 1792–1815. 28

奥地利的弱点,在18世纪初反对路易十四的同盟战争和18世纪末反对波拿巴的同盟战争中,也许反而不如在这之间的那些战争冲突中暴露得更充分。特别是1740年以后针对普鲁士的长期战争最能说明问题,它向人们表明:虽然这一时期在哈布斯堡领土上进行了军事、财政和行政管理改革,维也纳仍不能战胜另一个比它小的德意志国家,后者在军队、收入筹集和官僚机构管理效率等方面都要有效得多。此外,非日耳曼国家,法国、英国和俄国的意图也越来越清楚,它们既不希望奥地利消灭普鲁士,也不希望普鲁士吞并奥地利。从更大的欧洲范围来讲,哈布斯堡帝国已降为准一流大国,这种地位一直保持到1918年。它当然还没有跌落到西班牙和瑞典之类国家的地位,并且避免了落在波兰头上的命运。但是,由于它权力分散,民族众多,经济落后,维也纳历届政府要把它变成欧洲最强大国家的宏伟蓝图一次次地成为泡影。然而,要说奥地利已进入穷途末路还为时过早。正如奥尔温·赫夫顿所说,“奥地利帝国坚持拒绝趁机解散(对一些人来说简直是违反常理)。”这说明它仍然具有潜在力量。每一次灾难后,接踵而来的就是又一轮改革,即所谓“重建”。尽管维也纳在着手进行改革时总是困难重重,但帝国仍然拥有相当可观的潜力。每一个研究哈布斯堡王朝衰落的历史学者,对于1792—1815年近24年间面对法兰西帝国势不可挡的大军时,奥地利的军事抵抗所显示出的顽强,都会做出令人刮目相看的解释。

Prussia’s situation was very similar to Austria’s in geostrategical terms, although quite different internally. The reasons for that country’s swift rise to become the most powerful northern German kingdom are well known, and need only be listed here: the organizing and military genius of three leaders, the Great Elector (1640– 1688), Frederick William I (1713–1740), and Frederick “the Great” (1740–1786), the efficiency of the Junker-officered Prussian army, into which as much as fourfifths of the state’s taxable resources were poured; the (relative) fiscal stability, based upon extensive royal domains and encouragement of trade and industry; the willing use of foreign soldiers and entrepreneurs; and the famous Prussian bureaucrats operating under the General War Commissariat. 29 Yet it was also true that Prussia’s rise coincided with the collapse of Swedish power, with the disintegration of the chaotic, weakened Polish kingdom, and with the distractions which the many wars and uncertain succession of the Habsburg Empire imposed upon Vienna in the early decades of the eighteenth century. If Prussian monarchs seized their opportunities, therefore, the fact was that the opportunities were there to be seized. Moreover, in filling the “power vacuum” which had opened up in north-central Europe after 1770, the Prussian state also benefited from its position vis-à-vis the other Great Powers. Russia’s own rise was helping to distract (and erode) Sweden, Poland, and the Ottoman Empire. And France was far enough away in the west to be not usually a mortal danger; indeed, it could sometimes function as a useful ally against Austria. If, on the other hand, France pushed aggressively into Germany, it was likely to be opposed by Habsburg forces, Hanover (and therefore Britain), and perhaps the Dutch, as well as by Prussia itself. Finally, if that coalition failed, Prussia could more easily sue for peace with Paris than could the other powers; an anti-French alliance was sometimes useful, but not imperative, for Berlin.

普鲁士的情形,在地理战略上同奥地利十分类似,尽管他们国内情形大不相同。普鲁士的迅速崛起并成为北部德意志最强大王国的原因是尽人皆知的,这里只需要列举一下:大选帝侯(1640—1688年在位)、腓特烈·威廉一世(1713—1740年在位)和腓特烈大帝(1740—1786年在位)等三位领袖的组织和军事天才;由容克贵族充当军官、花掉国家赋税收入4/5的一支英勇善战的普鲁士大军;建立在规模广大的王室产业以及政府对工商业的鼓励基础上的相对的财政稳定;雇佣外籍士兵,任用外国企业家;以及在军需总监领导下闻名于世的普鲁士官僚机构。而且,普鲁士生逢其时,正赶上瑞典的崩溃和动乱不安,混乱而衰微的波兰被瓜分豆剖,而维也纳在18世纪初的几十年中又被一场场战争和哈布斯堡帝国王位继承问题搅得狼狈不堪,这些都是的的确确的。因此,如果普鲁士国王们能抓住良机的话,实际上有许多绝妙机会在等着他们。不仅如此,在填补1770年后北欧出现的“权力真空”时,普鲁士还从它与其他大国所处的相对地理位置上获益匪浅。俄国本身的崛起,有助于牵制(或削弱)瑞典、波兰和奥斯曼帝国。而法国又远在西方,通常构不成致命的威胁。事实上,法国有时还可以作为普鲁士反对奥地利的同盟。另一方面,如果法国大举入侵德意志的话,法国就很有可能遭到哈布斯堡、汉诺威(因而还有英国),可能还有荷兰以及普鲁士的反抗。最后,如果这一联盟失败,普鲁士比其他国家更容易同法国握手言和。对于柏林来说,反法联盟有时是有用的,但并非必须参加。

Within this advantageous diplomatic and geographical context, the early kings of Prussia played the game well. The acquisition of Silesia—described by some as the industrial zone in the east—was in particular a great boost to the state’s militaryeconomic capacity. But the limitations of Prussia’s real power in European affairs, limitations of size and population, were cruelly exposed in the Seven Years War of 1756–1763, when the diplomatic circumstances were no longer so favorable and Frederick the Great’s powerful neighbors were determined to punish him for his deviousness. Only the stupendous efforts of the Prussian monarch and his welltrained troops—assisted by the lack of coordination among his foes—enabled Frederick to avoid defeat in the face of such a frightening “encirclement. ” Yet the costs of that war in men and material were enormous, and with the Prussian army steadily ossifying from the 1770s onward, Berlin was in no position to withstand later diplomatic pressure from Russia, let alone the bold assault of Napoleon in 1806. Even the later recovery led by Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and the other military reformers could not conceal the still inadequate bases of Prussian strength by 1813– 1815. 30 It was by then overshadowed, militarily, by Russia; it relied heavily upon subsidies from Britain, paymaster to the coalition; and it still could not have taken on France alone. The kingdom of Frederick William III (1797–1840) was, like Austria, among the least of the Great Powers and would remain so until its industrial and military transformation in the 1860s.

普鲁士的早期国王们拥有外交和地理上的种种有利条件,他们纵横捭阖,得心应手。夺取被一些人称之为东部工业区的西里西亚,极大地增强了普鲁士的军事经济实力。但是当外交关系不再那么有利时,当腓特烈大帝强大的邻国决心对他的狡诈进行惩罚时,普鲁士在欧洲事务中实际力量的不足,它有限的版图和人口的弱点在七年战争中就暴露出来了。仅仅由于普鲁士国王及其训练有素的军队不屈不挠的努力,加上他的敌人之间缺乏合作精神,才使腓特烈面对可怕的“包围”得以侥幸逃脱覆灭的危险。但是这场战争使普鲁士在人力物力上都损失惨重,加上18世纪70年代以后它的军队固步自封,逐渐僵化,柏林根本无力抵抗以后来自俄国的外交压力,更不用说抵抗1806年拿破仑的大胆攻击了。即使晚些时候由沙恩霍尔斯特、格奈森瑙和其他军事改革家领导的重建工作,也无法掩盖其1813—1815年间仍然虚弱的国力。军事上,它那时已经处在俄国的下风。经济上严重依赖来自盟国供款者英国的津贴。它独自还是对付不了法国。腓特烈·威廉三世(1797—1840年在位)的王国像奥地利一样,在一流大国的行列间排在末席,并且一直到18世纪60年代工业和军事变革以前都是如此。

By contrast, two more distant powers, Russia and the United States, enjoyed a relative invulnerability and a freedom from the strategical ambivalences which plagued the central European states in the eighteenth century. Both of these future superpowers had, to be sure, “a crumbling frontier” which required watching; but neither in the American expansion across the Alleghenies and the great plains nor in the Russian expansion across the steppes did they encounter militarily advanced societies posing a danger to the home base. 31 In their respective dealings with occidental Europe, therefore, they had the advantage of a relatively homogeneous “front. ” They could each pose a challenge—or, at least, a distraction—to some of the established Great Powers, while still enjoying the invulnerability conferred by their distance from the main European battle zones.

与上述国家比较起来,两个遥远的大国,俄国和美国,相对说来固若金汤。它们没有18世纪困扰中欧国家的战略上两面临敌的困难。的确,这两个未来的超级大国都有一条“支离破碎的疆界”要防守,但无论美国穿越阿勒格尼山脉和大平原的扩张,还是俄国跨过亚细亚平原的扩张,都没有遇到军事上发达的国家对其后方基地造成威胁。它们各自在同西欧打交道时,都享有相对单一“战线”这样一个优势。它们谁都可以向一些已确立其地位的大国挑战或者至少造成一种牵制。同时两国由于远离欧洲战场,仍可以安享免遭攻击的地位。

Of course, in dealing with a period as lengthy as 1660 to 1815, it is important to stress that the impact of the United States and Russia was much more in evidence by the end of that era than at the beginning. Indeed, in the 1660s and 1670s, European “America” was no more than a string of isolated coastal settlements, while Muscovy before the reign of Peter the Great (1689–1725) was almost equally remote and even more backward; in commercial terms, each was “underdeveloped,” a producer of timber, hemp, and other raw materials and a purchaser of manufactured wares from Britain and the United Provinces. The American continent was, for much of this time, an object to be fought over rather than a power factor in its own right. What changed that situation was the overwhelming British success at the end of the Seven Years War (1763), which saw France expelled from Canada and Nova Scotia, and Spain excluded from West Florida. Freed from the foreign threats which hitherto had induced loyalty to Westminster, American colonists could now insist upon a merely nominal link with Britain and, if denied that by an imperial government with different ideas, engage in rebellion. By 1776, moreover, the North American colonies had grown enormously: the population of two million was by then doubling every thirty years, was spreading out westward, was economically prosperous, and was self-sufficient in foodstuffs and many other commodities. This meant, as the British found to their cost over the next seven years, that the rebel states were virtually invulnerable to merely naval operations and were also too extensive to be subjected by land forces drawn from a home island 3,000 miles away.

当然,谈到1660年到1815年这样漫长的一段时期,应该强调美国和俄国的影响在这一时期末比这一时期初更加明显。实际上,在17世纪60和70年代,欧洲人的“美洲”不过是一些孤立的沿海定居点。而彼得大帝统治(1689—1725年)之前的莫斯科公国,几乎是同样遥远,甚至更加落后。在贸易上,两者都是“不发达”国家,是木材、大麻和其他原料的生产国,都是从英国和联合省采购工业品的国家。在这一时期的大部分时间里,与其说美洲大陆是一个实力因素,毋宁说它自己是列国角逐的对象。是英国在七年战争结束时(1763年)压倒一切的胜利改变了这种情况。这次战争的结果使法国被赶出新斯科舍和加拿大,西班牙被赶出新佛罗里达。一旦消除了以前促使他们效忠于威斯敏斯特的外国威胁,美洲的殖民者们这时就可以坚持认为,他们同英国仅仅是一种名义上的联系,如果哪个帝国政府以某种原因否认这一点,就会招致叛乱。更何况到1776年北美殖民地迅速发展壮大起来。在这以前,它的200万人口每30年翻一番;它们向西扩展,经济上欣欣向荣,而且有自给自足的粮食和其他许多商品。正像英国人在以后7年付出大量代价才发现的那样,这意味着叛乱各州仅靠海战实际上是攻不破的,而靠从遥遥3000英里以外的本土岛屿调运陆军,也不可能降服这块大陆。

The existence of an independent United States was, over time, to have two major consequences for this story of the changing pattern of world power. The first was that from 1783 onward there existed an important extra-European center of production, wealth, and—ultimately—military might which would exert long-term influences upon the global power balance in ways which other extra-European (but economically declining) societies like China and India would not. Already by the mid-eighteenth century the American colonies occupied a significant place in the pattern of maritime commerce and were beginning the first hesitant stages of industrialization. According to some accounts, the emergent nation produced more pig iron and bar iron in 1776 than the whole of Great Britain; and thereafter, “manufacturing output increased by a factor of nearly 50 so that by 1830 the country had become the 6th industrial power of the developed world. ”32 Given that pace of growth, it was not surprising that even in the 1790s observers were predicting a great role for the United States within another century. The second consequence was to be felt much more swiftly, especially by Britain, whose role as a “flank” power in European politics was affected by the emergence of a potentially hostile state on its own Atlantic front, threatening its Canadian and West Indian possessions. This was not a constant problem, of course, and the sheer distance involved, together with the United States isolationism, meant that London did not need to consider the Americans in the same serious light as that in which, say, Vienna regarded the Turks or later the Russians. Nevertheless, the experiences of the wars of 1779–1783 and of 1812–1814 demonstrated all too clearly how difficult it would be for Britain to engage fully in European struggles if a hostile United States was at her back.

在一个时期内,一个独立美国的存在,对世界力量变化模式的历史产生了两大主要后果。其一是,从1783年以后,在欧洲以外出现了一个重要的生产、财富,最终是军事实力的中心。它对全球的实力对比产生了深远影响,而其他欧洲以外的国家(经济上正在没落的)如中国和印度是不能发挥这种影响的。早在18世纪中叶以前,美洲殖民地就已在海上贸易中占有重要的地位,并开始蹒跚地步入工业化的第一个阶段。根据一些材料,这个新独立的国家在1776年已生产出比整个大不列颠还要多的生铁和铁锭。这以后“产量增长了近50倍,以致到1830年美国已成为世界上发达国家中的第六大工业国”。这样的增长速度毫不奇怪。早在18世纪90年代就有观察家预言,美国在下一个世纪里将发挥更大的作用。第二个后果感觉到的时间要快得多,特别是英国,一个潜在的劲敌出现在英国大西洋的对面,威胁着英国的加拿大和西印第属地。英国在欧洲政治中作为“侧翼”大国的作用受到影响。当然,这个问题并不常常出现。由于距离遥远,加上美国的孤立主义,伦敦并不需要像维也纳看待土耳其人或稍后对待俄国人那样认真地看待美国人。然而,1779[5]—1783年和1812—1814年两次战争的经验教训清楚地表明,如果有一个敌对的美国在它背后,英国是多么难以全力从事欧洲的争夺。

The rise of czarist Russia had a much more immediate impact upon the international power balance. Russia’s stunning defeat of the Swedes at Poltava (1709) alerted the other powers to the fact that the hitherto distant and somewhat barbarous Muscovite state was intent upon playing a role in European affairs. With the ambitious first czar, Peter the Great, quickly establishing a navy to complement his new footholds on the Baltic (Karelia, Estonia, Livonia), the Swedes were soon appealing for the Royal Navy’s aid to prevent being overrun by this eastern colossus. But it was, in fact, the Poles and the Turks who were to suffer most from the rise of Russia, and by the time Catherine the Great had died in 1796 she had added another 200,000 square miles to an already enormous empire. Even more impressive seemed the temporary incursions which Russian military forces made to the west. The ferocity and frightening doggedness of the Russian troops during the Seven Years War, and their temporary occupation of Berlin in 1760, quite changed Frederick the Great’s view of his neighbor. Four decades later, Russian forces under their general, Suvorov, were active in both Italian and Alpine campaigning during the War of the Second Coalition (1798–1802)—a distant operation that was a harbinger of the relentless Russian military advance from Moscow to Paris which took place between 1812 and 1814. 33

沙皇俄国的崛起对国际力量对比有更直接的影响。俄国在波尔塔瓦(1709年)大败瑞典人,使其他大国面对这样一个事实:在此之前遥远而有点野蛮的莫斯科公国,决心在欧洲事务中占一席之地。第一个野心勃勃的沙皇彼得大帝迅速建立起一支海军以巩固其在波罗的海的新立足点(卡累利阿、爱沙尼亚、利沃尼亚)。瑞典人为避免被这个东方巨人所蹂躏,急忙向英国皇家海军求援。但实际上,受害最大的是土耳其人和波兰人。到1796年叶卡捷琳娜女皇去世前,她又为已经十分庞大的帝国增加了20万平方英里的领土。俄国军队偶尔向西方的侵略似乎更令人侧目而视。俄国军队在七年战争中所表现出来的残暴和可怕的顽强,以及1760年他们对柏林的暂时占领,极大地改变了腓特烈大帝对其邻国的看法。40年之后,俄国军队在苏沃洛夫将军的率领下,在第二次反法同盟战争中(1798—1802年)积极参加了意大利战役和阿尔卑斯战役。这次远距离作战是1812年到1814年之间俄国军队不屈不挠地从莫斯科向巴黎推进的先声。

It is difficult to measure Russia’s rank accurately by the eighteenth century. Its army was often larger than France’s; and in important manufactures (textiles, iron) it was also making great advances. It was a dreadfully difficult, perhaps impossible country for any of its rivals to conquer—at least from the west; and its status as a “gunpowder empire” enabled it to defeat the horsed tribes of the east, and thus to acquire additional resources of manpower, raw materials, and arable land, which in turn would enhance its place among the Great Powers. Under governmental direction, the country was evidently bent upon modernization in a whole variety of ways, although the pace and success of this policy have often been exaggerated. There still remained the manifold signs of backwardness: appalling poverty and brutality, exceedingly low per capita income, poor communications, harsh climate, and technological and educational retardation, not to mention the reactionary, feckless character of so many of the Romanovs. Even the formidable Catherine was unimpressive when it came to economic and financial matters.

准确评定俄国在18世纪的地位是很困难的。它的军队人数常常超过法国,而且在重要的工业品生产(纺织、炼铁)方面取得长足的进步。它是任何敌国,至少是来自西部的敌国很难征服、或许根本不可能征服的国家。而俄国作为一个“火药帝国”的地位使它得以打败东方的游牧部落,从而获取更多的人力、原料和可耕地资源,这必然会增强它在列强中的地位。在政府的指导下,俄国显然决心全力实现现代化,尽管这一政策取得的进展和成就往往被夸大了。落后的现象仍然比比皆是:惊人的贫困和野蛮、极低的人均收入、闭塞的交通、恶劣的气候、落后的技术和教育,更不用说罗曼诺夫王朝许多人反动无能的品格了。即使是令人生畏的叶卡捷琳娜,在处理经济和财政事务时也没有多大作为。

Still, the relative stability of European military organization and technique in the eighteenth century allowed Russia (by borrowing foreign expertise) to catch up and then outstrip countries with fewer resources; and this brute advantage of superior numbers was not really going to be eroded until the Industrial Revolution transformed the scale and speed of warfare during the following century. In the period before the 1840s and despite the many defects listed above, Russia’s army could occasionally be a formidable offensive force. So much (perhaps threequarters) of the state’s finances were devoted to the military and the average soldier stoically endured so many hardships that Russian regiments could mount long-range operations which were beyond most other eighteenth-century armies. It is true that the Russian logistical base was often inadequate (with poor horses, an inefficient supply system, and incompetent officials) to sustain a massive campaign on its own —the 1813–1814 march upon France was across “friendly” territory and aided by large British subsidies; but these infrequent operations were enough to give Russia a formidable reputation and a leading place in the councils of Europe even by the time of the Seven Years War. In grand-strategical terms, here was yet another power which could be brought into the balance, thus helping to ensure that French efforts to dominate the continent during this period would ultimately fail.

尽管如此,18世纪时欧洲军事组织和技术的相对停滞使得俄国(通过借鉴外国的长处)赶上并超过资源缺乏的国家。俄国人口众多这一原始优势只是到了下一个世纪工业革命改变了战争的规模和速度时才被削弱。在19世纪40年代之前,尽管有上面提到的种种缺陷,俄国军队有时还是一支强大的进攻力量。国家财政的大部分(也许有3/4)拨给了军队,而一般士兵又都吃苦耐劳,这样,俄国的军队才得以发动远距离作战。而这样的战役是18世纪其他多数国家的军队所不能发动的。不错,俄国的后勤供应经常都跟不上需求(劣等的马匹、低效的供应系统、不称职的军官),不能独自进行大规模作战。而1813—1814年向法国的进军全靠着通过“友邦”的领土和英国的大笔资助。但这些偶尔的作战行动足以给俄国一个令人生畏的名声,甚至早在七年战争前它就在一些欧洲会议中占据了一个重要地位。人们看到,在大战略方面,还有另一个大国可以引入欧洲均势中来,因而有助于保证挫败这一时期法国主宰欧洲大陆的图谋。

It was, nonetheless, to the distant future that early-nineteenth-century writers such as de Tocqueville usually referred when they argued that Russia and the United States seemed “marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe. ”34 In the period between 1660 and 1815 it was a maritime nation, Great Britain, rather than these continental giants, which made the most decisive advances, finally dislodging France from its position as the greatest of the powers. Here, too, geography played a vital, though not exclusive, part. This British advantage of location was described nearly a century ago in Mahan’s classic work The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1890):

18世纪初的作家们,如德·托克维尔论证说,俄国和美国似乎是“上帝意志选定出来支配半个地球命运的”,但他们这样说的时候,仍然通常是指遥远的未来。在1660年到1815年这一时期,取得最决定性进展,最终把法国从最强大国家之一的地位上赶下来的,是海上大国大不列颠,而不是这些陆上大国。这里地理因素起了极其重要的作用。虽然不是唯一的作用。英国所处的有利位置,在近一个世纪前马汉的经典著作《制海权对历史的影响》(1890年)一书中就得到描述:

… if a nation be so situated that it is neither forced to defend itself by land nor induced to seek extension of its territory by way of land, it has, by the very unity of its aim directed upon the sea, an advantage as compared with a people one of whose boundaries is continental. 35

……如果一个国家占有这样的地利,使它既不必在陆上保卫自己,也不可能存有从陆上扩张其领土野心,那么,同一个拥有陆上疆界的国家相比,由于它的目标是一心一意地指向海洋,它就占有一种优势。

Mahan’s statement presumes, of course, a number of further points. The first is that the British government would not have distractions on its flanks—which after the conquest of Ireland and the Act of Union with Scotland (1707), was essentially correct, though it is interesting to note those occasional later French attempts to embarrass Britain along the Celtic fringes, something which London took very seriously indeed. An Irish uprising was much closer to home than the strategical embarrassment offered by the American rebels. Fortunately for the British, this vulnerability was never properly exploited by foes.

当然,马汉的论点是以下面几点作为假定条件的。第一,英国政府不必为其侧翼分心。在英国征服爱尔兰和颁布《苏格兰合并法》后,侧翼基本上平安无事。有意思的是,伦敦对法国在凯尔特人居住的边缘地区偶尔进行的骚扰活动看得十分严重。爱尔兰人的起义比美洲殖民地的暴动离英国家门口近得多,虽然后者给英国造成战略上的困难,但值得英国人庆幸的是,它的这一弱点从未被它的敌人很好地加以利用。

The second assumption in Mahan’s statement is the superior status of sea warfare and of sea power over their equivalents on land. This was a deeply held belief of what has been termed the “navalist” school of strategy,36 and seemed well justified by post-1500 economic and political trends. The steady shift in the main trade routes from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic and the great profits which could be made from colonial and commercial ventures in the West Indies, North America, the Indian subcontinent, and the Far East naturally benefited a country situated off the western flank of the European continent. To be sure, it also required a government aware of the importance of maritime trade and ready to pay for a large war fleet. Subject to that precondition, the British political elite seemed by the eighteenth century to have discovered a happy recipe for the continuous growth of national wealth and power. Flourishing overseas trade aided the British economy, encouraged seamanship and shipbuilding, provided funds for the national Exchequer, and was the lifeline to the colonies. The colonies not only offered outlets for British products but also supplied many raw materials, from the valuable sugar, tobacco, and calicoes to the increasingly important North American naval stores. And the Royal Navy ensured respect for British merchants in times of peace and protected their trade and garnered further colonial territories in war, to the country’s political and economic benefit. Trade, colonies, and the navy thus formed a “virtuous triangle,” reciprocally interacting to Britain’s long-term advantage.

马汉这段话的第二个假定条件是,海战和海上实力有超过陆战和陆上实力的地位。这是被称之为“海军第一主义”战略学派坚信不移的信念。而1500年以后经济和政治发展的潮流似乎也很好地证明了这一点。主要商路确定不移地从地中海转移到大西洋,给在西印度群岛、北美、印度次大陆和远东的殖民地和商业冒险带来了丰厚的利润,这一切都有利于位于欧洲大陆西翼的国家。的确,还需要有一个认识到海上贸易重要性的政府,这个政府要乐于为一支大规模的作战舰队支付款项。在这种先决条件下,英国的政治精英们似乎还在18世纪以前就已经找到了促进国家财富和实力不断增长的窍门。繁荣的海外贸易促进了英国经济,刺激了航海业和造船业的发展,为国家财政提供了资金,同时它还是通向殖民地的生命线。殖民地不仅为英国制成品提供了出路,还为英国提供了许多原料来源,从宝贵的糖、烟草、白棉布到越来越重要的北美航海用品。而且皇家海军为了英国政治和经济上的利益,在和平时期确保对本国商人的尊重,在战争时期保护他们的贸易并攫取更多的殖民地领土。这样,贸易、殖民地和海军就组成了一个“良性三角”,它们之间互相作用,保证了英国的长期优势。

While this explanation of Britain’s rise was partly valid, it was not the whole truth. Like so many mercantilist works, Mahan’s tended to emphasize the importance of Britain’s external commerce as opposed to domestic production, and in particular to exaggerate the importance of the “colonial” trades. Agriculture remained the fundament of British wealth throughout the eighteenth century, and exports (whose ratio to total national income was probably less than 10 percent until the 1780s) were often subject to strong foreign competition and to tariffs, for which no amount of naval power could compensate. 37 The navalist viewpoint also inclined to forget the further fact that British trade with the Baltic, Germany, and the Mediterranean lands was—although growing less swiftly than those in sugar, spices, and slaves—still of great economic importance;* so that a France permanently dominant in Europe might, as the events of 1806–1812 showed, be able to deliver a dreadful blow to British manufacturing industry. Under such circumstances, isolationism from European power politics could be economic folly.

虽然对英国崛起所作的这种解释部分是站得住脚的,但不能说明全部问题。像许多重商主义著作一样,马汉的著作也倾向于过分强调英国的对外贸易而忽视国内生产的作用,特别是夸大了“殖民地”贸易的作用。在整个18世纪,英国的农业始终是它财富的基础,而出口(它在国家总收入中所占的比重,直到18世纪80年代以前也许还不到10%)则常常遭受外国强有力的竞争和关税障碍,对于这一点,无论多么强大的海军力量都无济于事。海军第一主义所持的观点也喜欢忘记如下事实,那就是英国同波罗的海、德意志和地中海地区所进行的贸易,虽然比糖、香料和奴隶贸易增长要慢一些,但在经济上仍然有很大的重要性[6]。这就是为什么法国如果长期统治欧洲的话,就会像1806—1812年间的事件所表明的那样,可能给英国制造业带来沉重打击。在这种情况下,对欧洲政治不闻不问,采取孤立主义政策,从经济角度上讲就是愚蠢的。

There was also a critically important “continental” dimension to British grand strategy, overlooked by those whose gaze was turned outward to the West Indies, Canada, and India. Fighting a purely maritime war was perfectly logical during the Anglo-Dutch struggles of 1652–1654, 1665–1667, and 1672–1674, since commercial rivalry between the two sea powers was at the root of that antagonism. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, however, when William of Orange secured the English throne, the strategical situation was quite transformed. The challenge to British interests during the seven wars which were to occur between 1689 and 1815 was posed by an essentially land-based power, France. True, the French would take this fight to the western hemisphere, to the Indian Ocean, to Egypt, and elsewhere; but those campaigns, although important to London and Liverpool traders, never posed a direct threat to British national security. The latter would arise only with the prospect of French military victories over the Dutch, the Hanoverians, and the Prussians, thereby leaving France supreme in west-central Europe long enough to amass shipbuilding resources capable of eroding British naval mastery. It was therefore not merely William Ill’s personal union with the United Provinces, or the later Hanoverian ties, which caused successive British governments to intervene militarily on the continent of Europe in these decades. There was also the compelling argument—echoing Elizabeth I’s fears about Spain—that France’s enemies had to be given assistance inside Europe, to contain Bourbon (and Napoleonic) ambitions and thus to preserve Britain’s own long-term interests. A “maritime” and a “continental” strategy were, according to this viewpoint, complementary rather than antagonistic.

那些把眼光盯住西印度群岛、加拿大和印度的人忽视了另外一点,那就是英国大战略中具有重要意义的“大陆”因素。在1652—1654年、1665—1667年,以及1672—1674年英荷战争时期,同荷兰进行纯粹的海战是理所当然的,因为英荷这两个海上大国敌对的根源就是争夺海上贸易。但是1688年光荣革命后,奥伦治的威廉登上了英国王位。此后,英国的战略形势发生了很大转变。在1689年到1815年间发生的7次战争中,向英国利益发起挑战的,是一个以陆地为基地的法国。确实,法国想把这场战争引向西半球,引向印度洋、埃及和其他地方,但这些战斗虽然对伦敦和利物浦的商人至关重要,但绝没有对英国的国家安全造成直接威胁。只有当法国战胜荷兰、汉诺威和普鲁士,使法国在中、西欧主宰一切,使它有足够的时间积聚能够威胁英国海上霸权地位的造船物资,只有出现这种前景时,才会产生对英国国家安全的直接威胁。所以,这些年间英国历届政府对欧洲大陆进行的军事干涉绝不仅是因为威廉三世同联合省之间的个人联系,或后来汉诺威王朝的纽带关系。此外,还有一个颇令人信服的论据——这个论据反映了伊丽莎白一世对西班牙的恐惧,那就是,英国为了保护自身的长远利益,扼制波旁王朝(及拿破仑)的野心,必须给法国在欧洲大陆上的敌人以援助。根据这一观点,“海上”和“大陆”战略是相辅相成的,而不是互相排斥的。

The essence of this strategic calculation was nicely expressed by the Duke of Newcastle in 1742:

纽卡斯尔公爵在1742年很明确地表述了这一战略意图的要旨:

France will outdo us at sea when they have nothing to fear on land. I have always maintained that our marine should protect our alliances on the Continent, and so, by diverting the expense of France, enable us to maintain our superiority at sea. 38

一旦在大陆上消除了后顾之忧,法国就将会在海上超过我们。我一贯主张我们的海军应当保护我们在欧洲大陆上的盟国,借以牵制法国的力量,保证我们的海上优势。

This British support to countries willing to “divert the expense of France” came in two chief forms. The first was direct military operations, either by peripheral raids to distract the French army or by the dispatch of a more substantial expeditionary force to fight alongside whatever allies Britain might possess at the time. The raiding strategy seemed cheaper and was much beloved by certain ministers, but it usually had negligible effects and occasionally ended in disaster (like the expedition to Walcheren of 1809). The provision of a continental army was more expensive in terms of men and money, but, as the campaigns of Marlborough and Wellington demonstrated, was also much more likely to assist in the preservation of the European balance.

英国对于想“牵制法国力量”的国家的支持,主要有两种形式。第一种形式是采取直接的军事行动,或者进行骚扰以牵制法军,或派遣比较强大的远征军与英国当时的盟国并肩作战。骚扰战略所付的代价看来不大,因此受到大臣的偏爱,但其效果常常微不足道,有时竟以失败而告终(如1809年的对瓦尔克伦的远征)。就人力和经费来说,供应一支大陆远征军的花费要大得多,但是,像马尔伯勒和威灵顿将军指挥的战争所展示的那样,一支大陆远征军更有助于维持欧洲均势。

The second form of British aid was financial, whether by directly buying Hessian and other mercenaries to fight against France, or by giving subsidies to the allies. Frederick the Great, for example, received from the British the substantial sum of £675,000 each year from 1757 to 1760; and in the closing stages of the Napoleonic War the flow of British funds reached far greater proportions (e. g. , £11 million to various allies in 1813 alone, and £65 million for the war as a whole). But all this had been possible only because the expansion of British trade and commerce, particularly in the lucrative overseas markets, allowed the government to raise loans and taxes of unprecedented amounts without suffering national bankruptcy. Thus, while diverting “the expense of France” inside Europe was a costly business, it usually ensured that the French could neither mount a sustained campaign against maritime trade nor so dominate the European continent that they would be free to threaten an invasion of the home islands—which in turn permitted London to finance its wars and to subsidize its allies. Geographical advantage and economic benefit were thus merged to enable the British brilliantly to pursue a Janus-faced strategy: “with one face turned towards the Continent to trim the balance of power and the other directed at sea to strengthen her maritime dominance. ”39

英国采取的第二种方式是财政援助。或是出钱组织雇佣军来同法国作战,或是直接资助同盟国。例如,从1757年到1760年腓特烈大帝每年从英国得到多达675.1万英镑的资助。在拿破仑战争末期,英国财政援助的数额就更大了(例如,仅1813年它就给各盟国1 100万英镑,在整个战争中它提供了6 500万英镑的援助)。英国之所以能拿出这么多钱来,主要是因为商业和贸易的日益增长带来了丰厚的利润,特别是有利可图的海外市场的繁荣,容许英国政府以空前规模借债和征税,而不致使国家财政破产。所以,尽管英国在欧洲大陆上牵制干涉“法国力量”是非常花费钱财的,但它往往能保证法国无法对英国海上贸易发动持久的进攻,也无法控制欧洲大陆,这样,它也就无法腾出手来对英国本岛构成进攻性威胁。而这必然会使伦敦有可能筹集战费并资助其同盟国。地理上的优越性和经济利益结合在一起,使英国得以实行其两面战略:“一面转向欧洲大陆,调整均势;另一面则指向大海,加强其制海权。”

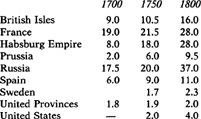

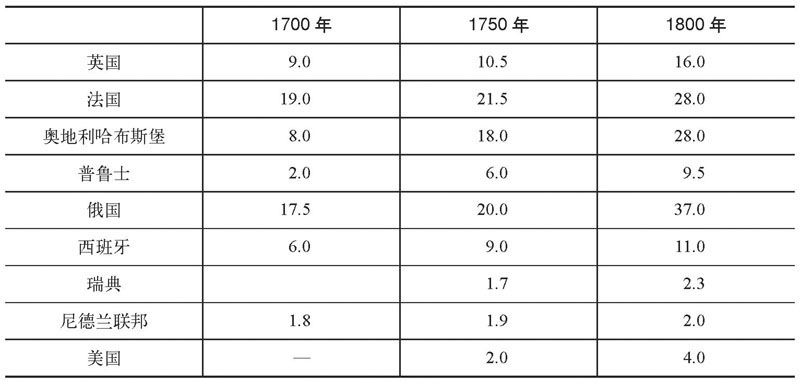

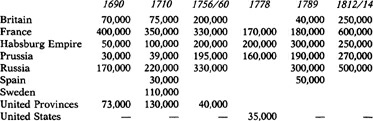

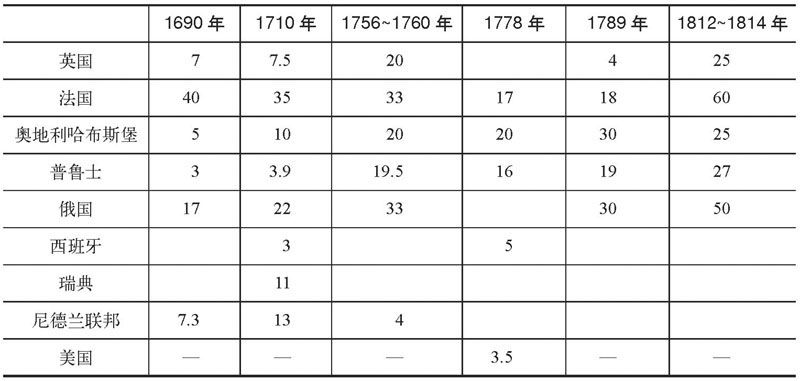

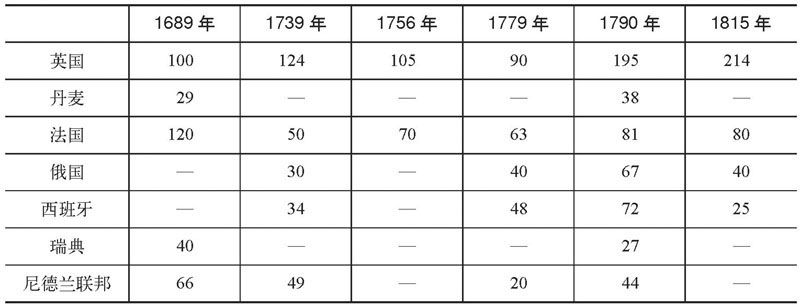

Only after one grasps the importance of the financial and geographical factors described above can one make full sense of the statistics of the growing populations and military/naval strengths of the powers in this period (see Tables 3–5).

只有掌握了上述的财政因素和地理因素的重要性以后,才能充分理解这一时期列强人口增长和陆军/海军力量增长的统计数字。(见表3、表4、表5)

Table 3. Populations of the Powers, 1700-180040

表3.列强的人口(1700—1800年)(单位:百万人)

表4.陆军规模(1690—1814年)(单位:万人)

表5.海军规模(1689—1815年)(主力舰数量)

As readers familiar with statistics will be aware, such crude figures have to be treated with extreme care. Population totals, especially in the early period, are merely guesses (and in Russia’s case the margin for error could be several millions). Army sizes fluctuated widely, depending upon whether the date chosen is at the outset, the midpoint, or the culmination of a particular war; and the total figures often include substantial mercenary units and (in Napoleon’s case) even the troops of reluctantly co-opted allies. The number of ships of the line indicated neither their readiness for battle nor, necessarily, the availability of trained crews to man them. Moreover, statistics take no account of generalship or seamanship, of competence or neglect, of national fervor or faintheartedness. Even so, it might appear that the above figures at least roughly reflect the chief power-political trends of the age: France and, increasingly, Russia lead in population and military terms; Britain is usually unchallenged at sea; Prussia overtakes Spain, Sweden, and the United Provinces; and France comes closer to dominating Europe with the enormous armies of Louis XIV and Napoleon than at any time in the intervening century.

熟悉统计的读者都知道,对待这些粗略的数字应当极为谨慎。人口总数,特别是早期人口数,仅仅是推测出来的(拿俄国来说,人口数据的误差可达几百万)。陆军的规模变动很大,这主要取决于所选定的日期是一场特定战争的开头、中期,还是在最高潮。而且总数中还常常包括大量雇佣军(例如拿破仑的军队),甚至有被迫参战的同盟国部队。主力舰数量不能说明其战备状态,也不意味着它们配备有训练有素的水兵。此外,统计数字并没有把指挥才能和航海技术考虑在内,也没有表明船员是否称职或疏于职守,是否有爱国热忱或怯懦胆小。尽管如此,上述数字至少还是粗略地反映了这一时期强权政治的主要趋向:在人口总数和陆军规模上,法国和迎头赶上的俄国名列榜首;英国的海上地位坚不可摧;普鲁士赶上了西班牙、瑞典和联合省;在路易十四和拿破仑统治时,法国拥有大量军队。在这近一个世纪期间,法国在这两个人的统治下比历史上的任何时候都更接近于主宰欧洲。

Aware of the financial and geographical dimensions of these 150 years of Great Power struggles, however, one can see that further refinements have to be made to the picture suggested in these three tables. For example, the swift decline of the United Provinces relative to other nations in respect to army size was not repeated in the area of war finance, where its role was crucial for a very long while. The nonmilitary character of the United States conceals the fact that it could pose a considerable strategical distraction. The figures also understate the military contribution of Britain, since it might be subsidizing 100,000 allied troops (in 1813, 450,000!) as well as providing for its own army, and naval personnel of 140,000 in 1813–1814;43 conversely, the true strength of Prussia and the Habsburg Empire, dependent on subsidies during most wars, would be exaggerated if one merely considered the size of their armies. As noted above, the enormous military establishments of France were rendered less effective through financial weaknesses and geostrategical obstacles, while those of Russia were eroded by economic backwardness and sheer distance. The strengths and weaknesses of each of these Powers ought to be borne in mind as we turn to a more detailed examination of the wars themselves.

然而,了解了这150年间列强争霸中的财政因素和地理因素以后,人们就可以看到,必须进一步理解上述三个表格所勾画的图景。例如,在陆军规模上,相对其他国家而言,联合省的力量迅速衰落了。但这种衰落并不表现在军事财政方面,相反,在这方面,它在一个长时期里,都起了重要作用。美国在军事上相对弱小,这一特点掩盖了它仍可以在战略上极大地牵制对手的事实。上述数字同样地低估了英国的军事贡献,因为1813—1814年它在维持自己的陆军和拥有14万人的海军的同时,还资助了同盟国约10万人的军队(1813年是45万!)。相反,在分析陆军规模时,在大部分战争中依靠外国财政资助的普鲁士和哈布斯堡帝国的实力往往是被夸大了。正如前面所提到的,法国庞大的军队由于资金不足和地理战略的障碍,战斗力较弱。俄国军队则因经济落后和战线太长而被削弱。当我们接下来研究这些战争本身时,应该记住各大国的实力和弱点。