The Eclipse of the Non-European World

欧洲之外

Before discussing the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon the Great Power system, it will be as well to understand its impacts farther afield, especially upon China, India, and other non-European societies. The losses they suffered were twofold, both relative and absolute. It was not the case, as was once fancied, that the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America lived a happy, ideal existence prior to the impact of western man. “The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic of any country before its industrial revolution and modernization is poverty. … with low productivity, low output per head, in traditional agriculture, any economy which has agriculture as the main constituent of its national income does not produce much of a surplus above the immediate requirements of consumption. … ”10 On the other hand, in view of the fact that in 1800 agricultural production formed the basis of both European and non-European societies, and of the further fact that in countries such as India and China there also existed many traders, textile producers, and craftsmen, the differences in per capita income were not enormous; an Indian handloom weaver, for example, may have earned perhaps as much as half of his European equivalent prior to industrialization. What this also meant was that, given the sheer numbers of Asiatic peasants and craftsmen, Asia still contained a far larger share of world manufacturing output* than did the much less populous Europe before the steam engine and the power loom transformed the world’s balances.

在讨论产业革命对大国体制的种种影响之前,我们也不妨了解一下它对远方,特别是对中国、印度和其他非欧洲社会的影响。它们蒙受的损失是双重的,既是相对的,又是绝对的。情况并不像人们一度想象的那样,即在西方人的冲击以前,亚洲、非洲和拉丁美洲各民族过着一种幸福和理想的生活。“基本的真相必须强调,即在经历产业革命和现代化以前的这些国家的特点就是贫困……低生产力、人均产量低下、处于传统农业状态、农业作为其国民收入主要组成部分的任何经济,都不能生产超过直接消费需要的很多剩余……”但在另一方面,鉴于农业生产在1800年形成了欧洲社会和非欧洲社会的基础这一事实,还鉴于诸如印度和中国等国家也存在许多商人、纺织品生产者和手工业者的事实,人均收入的差别并不很大。例如,一个印度手织机织工可能挣到工业化以前欧洲织工收入的一半。这又意味着,由于亚洲农民和手工业者的净人数较多,在蒸汽机和动力织机改变世界的均势之前,亚洲比人口少得多的欧洲在世界制造业的产量中[2]占有更为巨大的份额。

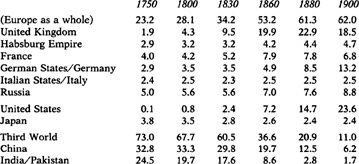

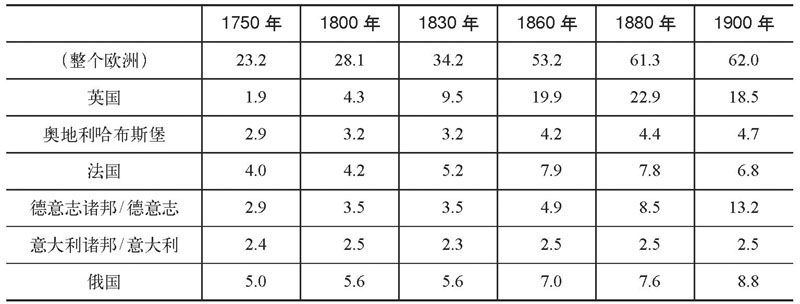

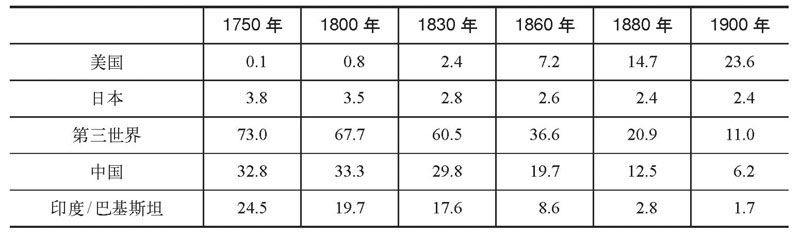

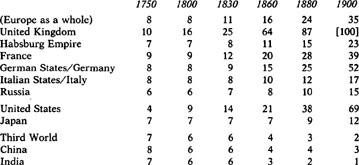

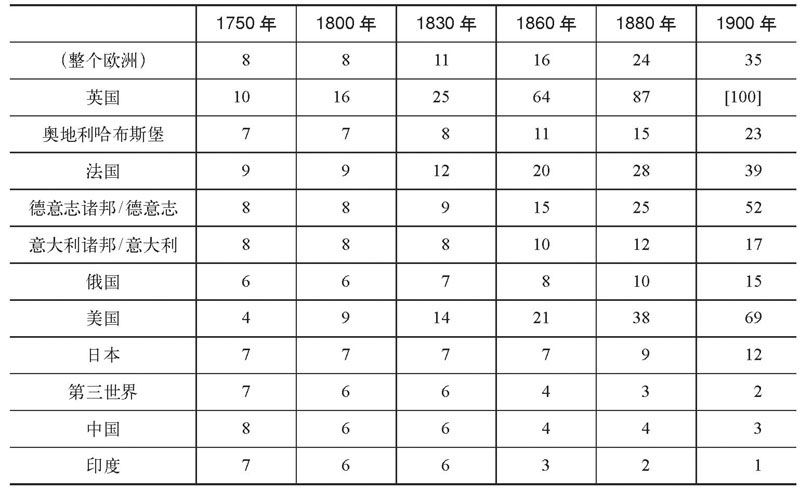

Just how dramatically those balances shifted in consequence of European industrialization and expansion can be seen in Bairoch’s two ingenious calculations (see Tables 6–7). 11

在贝罗克的两个有独创性的计算(见表6和表7)中可以看出,由于欧洲的工业化和扩张的缘故,力量对比的转变是多么鲜明。

Table 6. Relative Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1750-1900

表6 世界制造业产量的相对份额(1750~1900年)

Table 7. Per Capita Levels of Industrialization, 1750–1900

表7 按人口计算的工业化水平(1750~1900年)

(relative to U. K. in 1900 = 100)

(以1900年的英国为100)

The root cause of these transformations, it is clear, lay in the staggering increases in productivity emanating from the Industrial Revolution. Between, say, the 1750s and the 1830s the mechanization of spinning in Britain had increased productivity in that sector alone by a factor of 300 to 400, so it is not surprising that the British share of total world manufacturing rose dramatically—and continued to rise as it turned itself into the “first industrial nation. ”12 When other European states and the United States followed the path to industrialization, their shares also rose steadily, as did their per capita levels of industrialization and their national wealth. But the story for China and India was quite a different one. Not only did their shares of total world manufacturing shrink relatively, simply because the West’s output was rising so swiftly; but in some cases their economies declined absolutely, that is, they deindustrialized, because of the penetration of their traditional markets by the far cheaper and better products of the Lancashire textile factories. After 1813 (when the East India Company’s trade monopoly ended), imports of cotton fabrics into India rose spectacularly, from 1 million yards (1814) to 51 million (1830) to 995 million (1870), driving out many of the traditional domestic producers in the process. Finally—and this returns us to Ashton’s point about the grinding poverty of “those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution”—the large rise in the populations of China, India, and other Third World countries probably reduced their general per capita income from one generation to the next. Hence Bairoch’s remarkable—and horrifying—suggestion that whereas the per capita levels of industrialization in Europe and the Third World may have been not too far apart from each other in 1750, the latter’s was only one-eighteenth of the former’s (2 percent to 35 percent) by 1900, and only one-fiftieth of the United Kingdom’s (2 percent to 100 percent).

很明显,这些变化的根本原因,在于产业革命迸发出来的生产力的惊人提高。比如说,在18世纪50年代至19世纪30年代期间,英国纺纱业的机械化,使单位生产力提高了300至400倍,所以英国在总的世界制造业中所占的份额激增就不足为奇了——随着它使自己成为“第一工业国”,其份额继续增加。当其他欧洲国家和美国也走上工业化的道路时,它们的份额也稳步增长,就像它们按人口计算的工业化水平及其国家财富一样。但是中国和印度的情况就迥然不同了。它们在总的世界制造业中的份额在相对减少(这完全是因为西方产量的迅速增长),而且在有些情况下,它们的经济在绝对意义上衰退了,也就是说,由于兰开夏纺织厂的更为价廉物美的产品对它们的传统市场的渗透,它们非工业化了。1813年以后(当时东印度公司的贸易垄断结束了),印度进口的棉织品激增,从100万码(1814年)增至5100万码(1830年),进而又增加到9.95亿码(1870年),在这一过程中,许多传统的国内生产者受到了挤压。最后一点又回到了艾什顿关于“那些只增加其人数而没有经历一场产业革命的人”遭受折磨人的贫困这一论点上来。中国、印度和其他第三世界国家人口的大量增加,很可能一代一代地减少了它们总的按人口计算的收入。由此,贝罗克提出了一个值得注意——也令人震惊——的见解:在1750年,欧洲和第三世界按人口计算的工业化水平相差还不太远,可是到了1900年,后者只是前者的l/18(2%∶35%),只是英国的1/50(2%∶100%)。

The “impact of western man” was, in all sorts of ways, one of the most noticeable aspects of the dynamics of world power in the nineteenth century. It manifested itself not only in a variety of economic relationships—ranging from the “informal influence” of coastal traders, shippers, and consuls to the more direct controls of planters, railway builders, and mining companies13—but also in the penetrations of explorers, adventurers, and missionaries, in the introduction of western diseases, and in the proselytization of western faiths. It occurred as much in the centers of continents—westward from the Missouri, southward from the Aral Sea—as it did up the mouths of African rivers and around the coasts of Pacific archipelagoes. If it eventually had its impressive monuments in the roads, railway networks, telegraphs, harbors, and civic buildings which (for example) the British created in India, its more horrific side was the bloodshed, rapine, and plunder which attended so many of the colonial wars of the period. 14 To be sure, the same traits of force and conquest had existed since the days of Cortez, but now the pace was accelerating. In the year 1800, Europeans occupied or controlled 35 percent of the land surface of the world; by 1878 this figure had risen to 67 percent, and by 1914 to over 84 percent. 15

“西方人的冲击”从各方面说,是19世纪世界强国力量所在的最值得注意的表现之一。它不但在各种各样的经济关系方面——从沿海商人、航运者和领事等“非正规的影响”,直到种植园主、铁路建设者、采矿公司的更直接的控制——表现自己,而且也在探险者、冒险家和传教士的渗透,在西方疾病的传入、西方信仰的传播等方面表现自己。它既在各个大陆的腹地——从密苏里往西,从咸海往南——出现,也发生在非洲各河流的河口和太平洋群岛沿岸的周围。如果说“西方人的冲击”(譬如说)于英国人在印度建造的道路、铁路网、电报、港口和非军事建筑中留下了引人注目的遗迹,那么,它的更可怕的一面,却是与这个时期那么多殖民战争同时出现的流血、掠夺和抢劫。的确,从科蒂兹[3]时代起,这种武力和征服的特点已经存在了,但这时其步伐正在加快。1800年,欧洲人占领和控制了世界土地面积的35%;到1878年,这个数字上升到67%;到1914年,达到84%以上。

The advanced technology of steam engines and machine-made tools gave Europe decisive economic and military advantages. The improvements in the muzzleloading gun (percussion caps, rifling, etc. ) were ominous enough; the coming of the breechloader, vastly increasing the rate of fire, was an even greater advance; and the Gatling guns, Maxims, and light field artillery put the final touches to a new “firepower revolution” which quite eradicated the chances of a successful resistance by indigenous peoples reliant upon older weaponry. Furthermore, the steam-driven gunboat meant that European sea power, already supreme in open waters, could be extended inland, via major waterways like the Niger, the Indus, and the Yangtze: thus the mobility and firepower of the ironclad Nemesis during the Opium War actions of 1841 and 1842 was a disaster for the defending Chinese forces, which were easily brushed aside. 16 It was true, of course, that physically difficult terrain (e. g. , Afghanistan) blunted the drives of western military imperialism, and that among non-European forces which adopted the newer weapons and tactics—like the Sikhs and the Algerians in the 1840s—the resistance was far greater. But whenever the struggle took place in open country where the West could deploy its machine guns and heavier weapons, the issue was never in doubt. Perhaps the greatest disparity of all was seen at the very end of the century, during the battle of Omdurman (1898), when in one half-morning the Maxims and Lee-Enfield rifles of Kitchener’s army destroyed 11,000 Dervishes for the loss of only forty-eight of their own troops. In consequence, the firepower gap, like that which had opened up in industrial productivity, meant that the leading nations possessed resources fifty or a hundred times greater than those at the bottom. The global dominance of the West, implicit since da Gama’s day, now knew few limits.

先进的蒸汽机技术和机制工具,使欧洲拥有决定性的经济和军事优势。滑膛枪炮(雷管、膛线等)的改进是十分不祥的;大大增加发射速度的后膛炮的发明甚至是更大的进步;格林机枪、马克沁机枪、轻型野战炮给一场新的“火力革命”作了最后几笔润色,这场革命在很大程度上消除了依靠陈旧武器的土著民族在抵抗中取胜的机会。此外,蒸汽推动的炮舰意味着已经称霸公海的欧洲海上强国,能够通过像尼日尔河、印度河和长江等大河道向内地扩张。这样,在1841~1842年鸦片战争的几次战役中,装甲舰“复仇女神号”的机动性和火力对中国的守军来说是一个灾难,他们轻易地被一扫而光。当然,险要的地形(例如阿富汗)的确可以减弱西方军事帝国主义的锐气,在那些采用新武器和新战术的非欧洲军队中——如19世纪40年代的锡克教徒和阿尔及利亚人——抵抗力量也的确强大得多。但是一旦战斗在西方能部署机枪和重武器的开阔地展开时,其结果从来没有人怀疑过。也许在19世纪末可以看到最大的差距:在1898年的恩图曼战役中,基钦纳[4]军队的马克沁机枪和恩菲尔德步枪在半个上午消灭了1.1万名伊斯兰教托钵僧,而自己的部队只损失了48人。结果,火力的差距,像工业生产力上已经出现的差距那样,意味着领先的国家拥有的资源,为最落后的国家的50倍或100倍,从达·伽马时代起尚不明显的西方的全球统治,这时几乎没有限界了。