18

Britain as Hegemon?

英国充当霸主?

If the Punjabis and Annamese and Sioux and Bantu were the “losers” (to use Eric Hobsbawm’s term)17 in this early-nineteenth-century expansion, the British were undoubtedly the “winners. ” As noted in the previous chapter, they had already achieved a remarkable degree of global preeminence by 1815, thanks to their adroit combination of naval mastery, financial credit, commercial expertise, and alliance diplomacy. What the Industrial Revolution did was to enhance the position of a country already made supremely successful in the preindustrial, mercantilist struggles of the eighteenth century, and then to transform it into a different sort of power. If (to repeat) the pace of change was gradual rather than revolutionary, the results were nonetheless highly impressive. Between 1760 and 1830, the United Kingdom was responsible for around “two-thirds of Europe’s industrial growth of output,”18 and its share of world manufacturing production leaped from 1. 9 to 9. 5 percent; in the next thirty years, British industrial expansion pushed that figure to 19. 9 percent, despite the spread of the new technology to other countries in the West. Around 1860, which was probably when the country reached its zenith in relative terms, the United Kingdom produced 53 percent of the world’s iron and 50 percent of its coal and lignite, and consumed just under half of the raw cotton output of the globe. “With 2 percent of the world’s population and 10 percent of Europe’s, the United Kingdom would seem to have had a capacity in modern industries equal to 40–45 percent of the world’s potential and 55–60 percent of that in Europe. ”19 Its energy consumption from modern sources (coal, lignite, oil) in 1860 was five times that of either the United States or Prussia/Germany, six times that of France, and 155 times that of Russia! It alone was responsible for one-fifth of the world’s commerce, but for two-fifths of the trade in manufactured goods. Over one-third of the world’s merchant marine flew under the British flag, and that share was steadily increasing. It was no surprise that the mid-Victorians exulted at their unique state, being now (as the economist Jevons put it in 1865) the trading center of the universe:

在19世纪初期的这次扩张中,如果说旁遮普人、安南人、苏族人[5]和班图人是“输家”(用埃里克·霍布斯鲍姆的话来说),那么英国人无疑是“赢家”。在前一章已经指出,到1815年他们已经引人注目地取得了全球的突出地位,这是由于他们把制海权、财政信用、商业才能和结盟外交巧妙地结合了起来。产业革命所做的,就是加强一个国家在18世纪产业革命前的重商主义斗争中已经取得的十分成功的地位,然后把它转变成另一种强国。如果说(再重复一遍)变化的步伐是渐进的,而不是革命性的,那么其结果却是非常引人注目的。在1760~1830年,英国占“欧洲工业产量增长的2/3”,它在世界制造业生产中的份额从1.9%一跃而为9.5%;在以后的30年中,英国工业的扩大又使这个数字上升到19.9%,尽管新技术扩散到了其他西方国家。在1860年前后,相对地说,英国可能达到了极盛时期,它生产了全世界铁的53%、煤和褐煤的50%,并且差一点儿消费了全球原棉产量的一半。“联合王国的人口占全世界人口的2%,占欧洲人口的10%,却似乎具有相当于全世界潜力40%~60%的现代工业能力。”在1860年,它消费的现代能源(煤、褐煤、石油)是美国或普鲁士/德意志的5倍,法国的6倍,俄国的155倍。它单独占有全世界商业的1/5,但是却占有制成品贸易的2/5。全世界1/3以上的商船飘扬着英国国旗,而且所占的比率正在日益增加。所以,维多利亚时代中期的英国人为他们无可匹敌的地位扬扬得意,(按照经济学家杰文斯1865年的说法)它这时是世界的贸易中心:

The plains of North America and Russia are our corn fields; Chicago and Odessa our granaries; Canada and the Baltic are our timber forests; Australasia contains our sheep farms, and in Argentina and on the western prairies of North America are our herds of oxen; Peru sends her silver, and the gold of South Africa and Australia flows to London; the Hindus and the Chinese grow tea for us, and our coffee, sugar and spice plantations are in all the Indies. Spain and France are our vineyards and the Mediterranean our fruit garden; and our cotton grounds, which for long have occupied the Southern United States, are now being extended everywhere in the warm regions of the earth. 20

北美和俄国的平原是我们的玉米地,芝加哥和敖德萨是我们的粮仓,加拿大和波罗的海是我们的林场,澳大利亚、西亚有我们的牧羊地,阿根廷和北美的西部草原有我们的牛群,秘鲁运来它的白银,南非和澳大利亚的黄金则流到伦敦,印度人和中国人为我们种植茶叶,而我们的咖啡、甘蔗和香料种植园则遍及东西印度群岛。西班牙和法国是我们的葡萄园;地中海是我们的果园;长期以来早就生长在美国南部的我们的棉花地,现在正在向地球所有的温暖区域扩展。

Since such manifestations of self-confidence, and the industrial and commercial statistics upon which they rested, seemed to suggest a position of unequaled dominance on Britain’s part, it is fair to make several other points which put this all in a better context. First—although it is a somewhat pedantic matter—it is unlikely that the country’s gross national product (GNP) was ever the largest in the world during the decades following 1815. Given the sheer size of China’s population (and, later, Russia’s) and the obvious fact that agricultural production and distribution formed the basis of national wealth everywhere, even in Britain prior to 1850, the latter’s overall GNP never looked as impressive as its per capita product or its stage of industrialization. Still, “by itself the volume of total GNP has no important significance”;21 the physical product of hundreds of millions of peasants may dwarf that of five million factory workers, but since most of it is immediately consumed, it is far less likely to lead to surplus wealth or decisive military striking power. Where Britain was strong, indeed unchallenged, in 1850 was in modern, wealth-producing industry, with all the benefits which flowed from it.

由于这种自信的表现和成为这种表现基础的工商业统计数字,似乎说明了英国无可匹敌的支配地位。从其他几个角度来论述这个问题,使之更加全面,这样做应该说是公平合理的。首先,虽然这样说有点迂腐,但在1815年以后的几十年,这个国家的国民生产总值不可能一直是世界上最大的。由于中国(和后来的俄国)的纯人口数字,以及农业的生产和分配构成了世界各地(甚至1850年前的英国)国民财富的基础这一明显的事实,英国的国民生产总值从来没有像它的人均产量和它的工业化程度那样令人瞩目。再说,“国民生产总值的量本身并无重要意义”,数亿农民的物质产量可以使500万工厂工人的产量相形失色,但由于他们生产的大部分都很快被消费了,所以远不可能形成剩余财富或决定性的军事打击力量。英国在1850年是强大的,它的确没有遇到挑战,它强就强在拥有现代的、创造财富的工业和由此产生的一切利益。

On the other hand—and this second point is not a pedantic one—Britain’s growing industrial muscle was not organized in the post-1815 decades to give the state swift access to military hardware and manpower as, say, Wallenstein’s domains did in the 1630s or the Nazi economy was to do. On the contrary, the ideology of laissez-faire political economy, which flourished alongside this early industrialization, preached the causes of eternal peace, low government expenditures (especially on defense), and the reduction of state controls over the economy and the individual. It might be necessary, Adam Smith had conceded in The Wealth of Nations (1776), to tolerate the upkeep of an army and a navy in order to protect British society “from the violence and invasion of other independent societies”; but since armed forces per se were “unproductive” and did not add value to the national wealth in the way that a factory or a farm did, they ought to be reduced to the lowest possible level commensurate with national safety. 22 Assuming (or, at least, hoping) that war was a last resort, and ever less likely to occur in the future, the disciples of Smith and even more of Richard Cobden would have been appalled at the idea of organizing the state for war. As a consequence, the “modernization” which occurred in British industry and communications was not paralleled by improvements in the army, which (with some exceptions)23 stagnated in the post-1815 decades.

其次(这第二点可不是迂腐的),英国日益增长的工业力量,在1815年以后的几十年里并没有组织起来以使国家迅速取得军事装备和人力上的升级,比如,像17世纪30年代华伦斯坦[6]做过的或纳粹经济将要做的那样。相反,与这一早期工业化同时盛行的放任主义政治经济思想,却宣扬长期和平、低政府开支(特别是防务)和减少国家对经济和个人的控制等目标。亚当·斯密在《国富论》(1776年)中承认,容许保持一支陆军和一支海军,以便保护英国社会“不受其他独立社会的暴力扰乱和入侵”,这可能是必要的;但是由于武装力量本身是“非生产性的”,不能像工厂和农场那样给国民财富增值,它们应该减少到与国家安全相称的尽可能低的水平。亚当·斯密的弟子们,尤其是理查德·科布登的弟子们假设(或者至少是希望)战争是最后采取的手段,在将来越发不可能发生,所以对组织国家准备战争的思想会感到吃惊。结果,英国的工业和交通出现了“现代化”,但军队的改进却没有跟上,军队(除了一些例外)在1815年以后的几十年停滞不前。

However preeminent the British economy in the mid-Victorian period, therefore, it was probably less “mobilized” for conflict than at any time since the early Stuarts. Mercantilist measures, with their emphasis upon the links between national security and national wealth, were steadily eliminated: protective tariffs were abolished; the ban on the export of advanced technology (e. g. , textile machinery) was lifted; the Navigation Acts, designed among other things to preserve a large stock of British merchant ships and seamen for the event of war, were repealed; imperial “preferences” were ended. By contrast, defense expenditures were held to an absolute minimum, averaging around £15 million a year in the 1840s and not above £27 million in the more troubled 1860s; yet in the latter period Britain’s GNP totaled about £1 billion. Indeed, for fifty years and more following 1815 the armed services consumed only about 2–3 percent of GNP, and central government expenditures as a whole took much less than 10 percent—proportions which were far less than in either the eighteenth or the twentieth century. 24 These would have been impressively low figures for a country of modest means and ambitions. For a state which managed to “rule the waves,” which possessed an enormous, far-flung empire, and which still claimed a large interest in preserving the European balance of power, they were truly remarkable.

因此,在维多利亚时代中期,不管英国经济地位是多么突出,它却比早期斯图亚特王朝的任何时候都更少地为冲突而进行“动员”。强调把国家安全与国民财富联系起来的各种重商主义措施,被坚定地排除了:保护性关税被取消,先进技术(例如纺织机械)出口的禁令被解除,保持一大批英国商船和海员以备战争的航海法被废除,王室的各种“优惠待遇”到此结束。对比之下,防务费用保持在绝对的最低水平上,19世纪40年代平均一年约为1500万英镑,在较为多事的60年代,也不超过2700万英镑;可是在后一个时期,英国的国民生产总值共约10亿英镑。的确,1815年以后50多年,武装力量只花费了英国国民生产总值的2%~3%,整个中央政府的费用远不足10%。这个比率,比18世纪或20世纪的比率要小得多。这些数字对一个具有适度手段和野心的国家来说也是很低的。对一个设法“统治四海”并声称其巨大利益在于保持欧洲均势的国家来说,这些数字真是值得注意的。

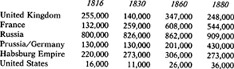

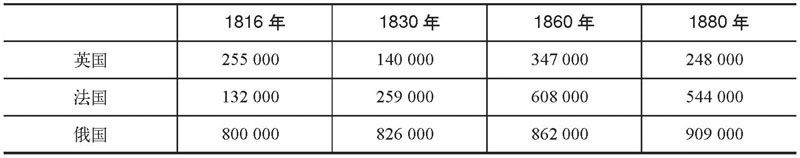

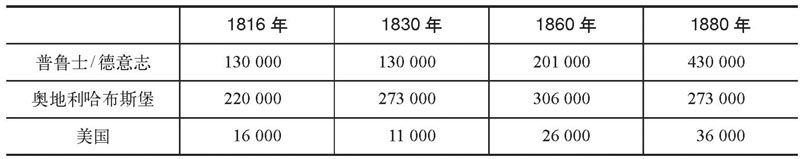

Like that of the United States in, say, the early 1920s, therefore, the size of the British economy in the world was not reflected in the country’s fighting power; nor could its laissez-faire institutional structures, with a minuscule bureaucracy increasingly divorced from trade and industry, have been able to mobilize British resources for an all-out war without a great upheaval. As we shall see below, even the more limited Crimean War shook the system severely, yet the concern which that exposure aroused soon faded away. Not only did the mid-Victorians show ever less enthusiasm for military interventions in Europe, which would always be expensive, and perhaps immoral, but they reasoned that the equilibrium between the continental Great Powers which generally prevailed during the six decades after 1815 made any full-scale commitment on Britain’s part unnecessary. While it did strive, through diplomacy and the movement of naval squadrons, to influence political events along the vital peripheries of Europe (Portugal, Belgium, the Dardanelles), it tended to abstain from intervention elsewhere. By the late 1850s and early 1860s, even the Crimean campaign was widely regarded as a mistake. Because of this lack of inclination and effectiveness, Britain did not play a major role in the fate of Piedmont in the critical year of 1859, it disapproved of Palmerston and Russell’s “meddling” in the Schleswig-Holstein affair of 1864, and it watched from the sidelines when Prussia defeated Austria in 1866 and France four years later. It is not surprising to see that Britain’s military capacity was reflected in the relatively modest size of its army during this period (see Table 8), little of which could, in any case, be mobilized for a European theater.

因此,英国在世界经济中的规模,并不反映这个国家的战斗力,就20世纪20年代的美国一样;它的放任主义的体制,连同一个日益脱离贸易和工业的很不重要的官僚机器,也不可能动员英国的资源去打一场全力以赴的战争而不引起大动乱。下面将会看到,即使是规模更有限的克里米亚战争,也严重地动摇着它的制度,可是,那种暴露出来的现象所引起的担心很快消失了。不但维多利亚时代中期的人对干涉欧洲的军事行动表现得比以往更不热心,因为这种干涉总是代价高昂的,也是不道德的;而且他们认为,1815年以后的60年,在欧洲大陆大国之间总的来说占上风的平衡,使英国不必去全面地承担义务。虽然它通过外交和调动海军舰队,的确在力求影响欧洲边缘要地(葡萄牙、比利时和达达尼尔海峡)的政治事件,但它倾向于避开对其他地方的干涉。到了19世纪50年代后期和60年代初期,甚至克里米亚之战也普遍被视为一个错误。由于英国如此缺乏意愿和实力,在危急的1859年,它对皮埃蒙特的命运并不起重要作用,它不同意巴麦尊勋爵和拉塞尔“插手”1864年石勒苏益格-荷尔斯泰因事件;当普鲁士在1866年打败奥地利,4年以后又打败法国时,它也袖手旁观。所以,看到英国的军事实力反映于这个时期它的陆军比较有节制地控制兵员(见表8)这一事实,就不会感到惊奇了。无论如何,它没有多少军队可以动员到欧洲战场上去。

Table 8. Military Personnel of the Powers, 1816-1880 25

表8 大国的兵员(1816~1880年)

Even in the extra-European world, where Britain preferred to deploy its regiments, military and political officials in places such as India were almost always complaining of the inadequacy of the forces they commanded, given the sheer magnitude of the territories they controlled. However imposing the empire may have appeared on a world map, district officers knew that it was being run on a shoestring. But all this is merely saying that Britain was a different sort of Great Power by the early to middle nineteenth century, and that its influence could not be measured by the traditional criteria of military hegemony. Where it was strong was in certain other realms, each of which was regarded by the British as far more valuable than a large and expensive standing army.

甚至在欧洲以外英国优先部署其部队的地方(像印度等地)的军政官员,由于他们控制了广袤的领土,也几乎一直抱怨他们指挥的兵力不足。不管这个帝国在世界地图上给人以多么深刻的印象,地方的官员却深知它是在惨淡经营。但这一切不过说明,到19世纪初期和中期,英国是另一种大国,它的影响不能用军事霸权的传统标准去衡量。它的强大,表现在其他某些领域,英国人认为这远比一支庞大而又花钱的常备陆军更有价值。

The first of these was in the naval realm. For over a century before 1815, of course, the Royal Navy had usually been the largest in the world. But that maritime mastery had frequently been contested, especially by the Bourbon powers. The salient feature of the eighty years which followed Trafalgar was that no other country, or combination of countries, seriously challenged Britain’s control of the seas. There was, it is true, the occasional French “scare”; and the Admiralty also kept a wary eye upon Russian shipbuilding programs and upon the American construction of large frigates. But each of those perceived challenges faded swiftly, leaving British sea power to exercise (in Professor Lloyd’s words) “a wider influence than has ever been seen in the history of maritime empires. ”26 Despite a steady reduction in its own numbers after 1815, the Royal Navy was at some times probably as powerful as the next three or four navies in actual fighting power. And its major fleets were a factor in European politics, at least on the periphery. The squadron anchored in the Tagus to protect the Porguguese monarchy against internal or external dangers; the decisive use of naval force in the Mediterranean (against the Algiers pirates in 1816; smashing the Turkish fleet at Navarino in 1827; checking Mehemet Ali at Acre in 1840); and the calculated dispatch of the fleet to anchor before the Dardanelles whenever the “Eastern Question” became acute: these were manifestations of British sea power which, although geographically restricted, nonetheless weighed in the minds of European governments. Outside Europe, where smaller Royal Navy fleets or even individual warships engaged in a whole host of activities—suppressing piracy, intercepting slaving ships, landing marines, and overawing local potentates from Canton to Zanzibar—the impact seemed perhaps even more decisive. 27

其中第一个是海军领域。当然,在1815年以前的一个多世纪中,一般地说皇家海军已经是世界上最大的海军力量。但是那种制海权常常要争夺,特别是要与波旁家族诸强争夺。特拉法尔加之战后的80年,突出的特征是,再也没有任何国家或联合起来的几个国家,能够严重地对英国的海上控制进行挑战了。不错,偶尔还有“恐法病”,海军部也密切地注意着俄国的造船计划和美国建造大型快速帆船的活动。但每一个这种可以觉察到的挑战都很快就消失了,只留下英国的海上力量发挥“比在以往诸海上帝国史中可以看到的更加广泛的影响”(劳埃德教授之言)。尽管皇家海军的数量在1815年以后稳步减少,但它的实际战斗力有时很可能与仅次于它的3支或4支海军的战斗力之和一样强大。它的主要舰队,至少在欧洲的边缘,是欧洲政治的一个因素。为了保护葡萄牙君主国免遭国内外的危险,舰队停泊在塔古斯河;它决定性地在地中海使用海军(在1816年对付阿尔及尔的海盗,1827年在纳瓦里诺击溃土耳其舰队,1840年在阿克里遏制穆罕默德·阿里);每当“东方问题尖锐化”时,它就老谋深算地派舰队停泊在达达尼尔海峡前。凡此种种都展示了英国的海上力量,这种力量虽然在地理上受到限制,但在欧洲各国政府的心中仍占有分量。在欧洲以外,较小的皇家海军舰队,甚或个别的战舰进行所有的活动:镇压海盗,拦截贩奴船只,运送陆战队登陆,威慑从广州到桑给巴尔的地方当权者。在那些地方,其影响甚至更是决定性的。

The second significant realm of British influence lay in its expanding colonial empire. Here again, the overall situation was a far less competitive one than in the preceding two centuries, where Britain had had to fight repeatedly for empire against Spain, France, and other European states. Now, apart from the occasional alarm about French moves in the Pacific or Russian encroachments in Turkestan, no serious rivals remained. It is therefore hardly an exaggeration to suggest that between 1815 and 1880 much of the British Empire existed in a power-political vacuum, which is why its colonial army could be kept relatively low. There were, it is true, limits to British imperialism—and certain problems, with the expanding American republic in the western hemisphere as well as with France and Russia in the eastern. But in many parts of the tropics, and for long periods of time, British interests (traders, planters, explorers, missionaries) encountered no foreigners other than the indigenous peoples.

英国势力的第二个重要的领域,表现在它的日益扩大的殖民地帝国上。在这方面,总的形势又远不像前两个世纪那样具有竞争性,那时英国不得不一再为其帝国而同西班牙、法国及其他欧洲国家交战。这时,除了对法国在太平洋的移动或俄国在土耳其斯坦的蚕食行动感到惊慌外,并没有需要认真对待的对手。因此,1815~1880年,英国经常存在于一种实力—政治的真空中,这很难说是夸张之词,这也是殖民军队能够保持在比较低的水平上的原因。不错,英国帝国主义有局限性和一些问题,还有西半球的扩张中的美利坚合众国及东半球的法国和俄国。但是,长期以来在热带的许多地方,除土著民族外,英国的利益集团(商人、种植园主、探险者和传教士)几乎碰不到其他外国人。

This relative lack of external pressure, together with the rise of laissez-faire liberalism at home, caused many a commentator to argue that colonial acquisitions were unnecessary, being merely a set of “millstones” around the neck of the overburdened British taxpayer. Yet whatever the rhetoric of anti-imperialism within Britain, the fact was that the empire continued to grow, expanding (according to one calculation) at an average annual pace of about 100,000 square miles between 1815 and 1865. 28 Some were strategical/commercial acquisitions, like Singapore, Aden, the Falkland Islands, Hong Kong, Lagos; others were the consequence of landhungry white settlers, moving across the South African veldt, the Canadian prairies, and the Australian outback—whose expansion usually provoked a native resistance that often had to be suppressed by troops from Britain or British India. And even when formal annexations were resisted by a home government perturbed at this growing list of new responsibilities, the “informal influence” of an expanding British society was felt from Uruguay to the Levant and from the Congo to the Yangtze. Compared with the sporadic colonizing efforts of the French and the more localized internal colonization by the Americans and the Russians, the British as imperialists were in a class of their own for most of the nineteenth century.

这种相对缺乏外界压力的情况,加上国内放任的自由主义的兴起,使许多评论家坚决认为没有必要去攫取殖民地,此举不过是挂在负担过重的英国纳税者脖子上的一套“磨石”。可是,不管英国国内反帝国主义的言论是多么动听,事实是帝国在继续发展,1815~1865年,年平均扩张速度约为10万平方英里。有些地方是为战略和商业而攫取的,像新加坡、亚丁、福克兰群岛、香港和拉各斯;其他地方则是白人殖民者对土地贪得无厌的结果,他们穿越南非的草原、加拿大的草原和澳大利亚人烟稀少的内地。他们的扩张通常激起当地人的反抗,以致英国或英属印度常常不得不派军队去镇压。即使为日益增加的新责任所苦的本国政府反对正式吞并,但从乌拉圭到黎凡特,从刚果到长江,人们仍能感觉到一个扩张中的英国社会的“非正式的影响”。与法国的时断时续的殖民活动及美国人和俄国人更局部性的内部殖民相比,在19世纪的大部分时期内,英国人作为帝国主义者来说,是自成一类的。

The third area of British distinctiveness and strength lay in the realm of finance. To be sure, this element can scarcely be separated from the country’s general industrial and commercial progress; money had been necessary to fuel the Industrial Revolution, which in turn produced much more money, in the form of returns upon capital invested. And, as the preceding chapter showed, the British government had long known how to exploit its credit in the banking and stock markets. But developments in the financial realm by the mid-nineteenth century were both qualitatively and quantitatively different from what had gone before. At first sight, it is the quantitative difference which catches the eye. The long peace and the easy availability of capital in the United Kingdom, together with the improvements in the country’s financial institutions, stimulated Britons to invest abroad as never before: the £6 million or so which was annually exported in the decade following Waterloo had risen to over £30 million a year by midcentury, and to a staggering £75 million a year between 1870 and 1875. The resultant income to Britain from such interest and dividends, which had totaled a handy £8 million each year in the late 1830s, was over £50 million a year by the 1870s; but most of that was promptly reinvested overseas, in a sort of virtuous upward spiral which not only made Britain ever wealthier but gave a continual stimulus to global trade and communications.

显示英国与众不同和国力的第三个方面,表现在财政领域上。诚然,这个因素是不可能脱离国家总的工商业进步的;必须用金钱给产业革命加油,而产业革命则以投资收益的形式转过来又创造更多的金钱。前一章已经谈到,英国政府早就知道怎样利用它的银行信贷和股票市场。但是到了19世纪中叶,财政领域的发展,不论在质的方面,还是在量的方面,都与以前的发展不同。乍一看来,量的差别引人注目。长期的和平以及在英国国内容易取得资本的事实,再加上全国金融体制的改进,从来没有如此刺激英国人向国外投资:在滑铁卢之战后的10年中,每年约输出600万英镑;到19世纪中叶已上升到一年3000万英镑以上;在1870~1875年,上升到惊人的7500万英镑。结果,英国从这类利息和红利中取得的收入,在19世纪30年代后期每年能不费劲地达到800万英镑,到19世纪70年代,每年超过5000万英镑。但大部分收入很快再向海外投资,呈上升的螺旋状,这样不但使英国越来越富,而且不断地推动全球的贸易和交通。

The consequences of this vast export of capital were several, and important. The first was that the returns on overseas investments significantly reduced the annual trade gap on visible goods which Britain always incurred. In this respect, investment income added to the already considerable invisible earnings which came from shipping, insurance, bankers’ fees, commodity dealing, and so on. Together, they ensured that not only was there never a balance-of-payments crisis, but Britain became steadily richer, at home and abroad. The second point was that the British economy acted as a vast bellows, sucking in enormous amounts of raw materials and foodstuffs and sending out vast quantities of textiles, iron goods, and other manufactures; and this pattern of visible trade was paralleled, and complemented, by the network of shipping lines, insurance arrangements, and banking links which spread outward from London (especially), Liverpool, Glasgow, and most other cities in the course of the nineteenth century.

大量输出资本的后果是多方面的,也是重要的。首先,海外投资的收益大大地缩小了英国一直承受的可见商品贸易的缺口。在这一方面,投资收入增加了来自航运、保险、银行业务、商品交易等方面已经相当可观的无形收益。这些收益合在一起,不但确保英国绝不会发生收支平衡的危机,而且英国在国内外变得越来越富了。其次,英国的经济起着一个巨大的风箱的作用,吞进大量原料和食品,吐出大量的纺织品、铁制品和其他制成品;与这类有形的贸易相媲美并补充其不足的是航运网络、保险机制和银行联系纽带。在19世纪,这些业务从伦敦(尤为突出)、利物浦、格拉斯哥和其他许多城市向外扩大。

Given the openness of the British home market and London’s willingness to reinvest overseas income in new railways, ports, utilities, and agricultural enterprises from Georgia to Queensland, there was a general complementarity between visible trade flows and investment patterns. * Add to this the growing acceptance of the gold standard and the development of an international exchange and payments mechanism based upon bills drawn on London, and it was scarcely surprising that the mid-Victorians were convinced that by following the principles of classical political economy, they had discovered the secret which guaranteed both increasing prosperity and world harmony. Although many individuals—Tory protectionists, oriental despots, newfangled socialists—still seemed too purblind to admit this truth, over time everyone would surely recognize the fundamental validity of laissez-faire economics and utilitarian codes of government. 29

由于英国国内市场的开放性和伦敦愿意把海外收入向从佐治亚直到昆士兰的新的铁路、港口、公用事业和农业企业进行再投资,在可见的贸易交流和投资类型之间存在着一种总的互补性[7]。除此之外,还有对金本位的日益接受和以向伦敦兑取的票据为基础的国际交换和支付机制的发展,所以以下情况不足为奇:维多利亚时代中期的人们相信,通过采用古典政治经济学的原理,他们已发现了既保证欣欣向荣又保证称霸世界的秘密。虽然有许多人——托利党的保护主义者、东方的专制君主——似乎仍过于迟钝而不承认这个真理,但经过这段时期,每个人肯定都会认识到放任主义经济学和政府功利主义准则的基本有效性。

While all this made Britons wealthier than ever in the short term, did it not also contain elements of strategic danger in the longer term? With the wisdom of retrospect, one can detect at least two consequences of these structural economic changes which would later affect Britain’s relative power in the world. The first was the way in which the country was contributing to the long-term expansion of other nations, both by establishing and developing foreign industries and agriculture with repeated financial injections and by building railways, harbors, and steamships which would enable overseas producers to rival its own production in future decades.

虽然这一切从短期来看使英国人比以往更富有,但从长期看,这是否也包含了战略上的危险因素?通过明智的回顾,人们至少能发现这些结构经济变化的两个后果,在以后将影响英国在世界上的力量对比。第一个是这个国家正在为其他国家的长期扩展做出贡献——既通过不断地投入资金以建立和发展外国的工农业,又通过建造铁路、港口和轮船而使海外生产者能在以后的几十年与自己的产品进行竞争。

In this connection, it is worth noting that while the coming of steam power, the factory system, railways, and later electricity enabled the British to overcome natural, physical obstacles to higher productivity, and thus increased the nation’s wealth and strength, such inventions helped the United States, Russia, and central Europe even more, because the natural, physical obstacles to the development of their landlocked potential were much greater. Put crudely, what industrialization did was to equalize the chances to exploit one’s own indigenous resources and thus to take away some of the advantages hitherto enjoyed by smaller, peripheral, naval-cum-commercial states and to give them to the great landbased states. 30

在这一方面值得指出的是,虽然蒸汽动力、制造业、铁路及后来的电力的来临,能使英国克服自然的和物质的障碍,从而提高生产力,增加了国家的财富和力量,但这些发明也帮助了美国、俄国,尤其是中欧,因为对内陆的发展而言,潜在的自然的和物质的障碍要大得多。用浅显的话来说,工业化所做的,就是使各国利用其本地资源的机会均等,从而扩展了迄今由那些较小的边缘国家所享受的海军兼商业的优势,而把这些优势转给了以陆地为基础的大国。

The second potential strategical weakness lay in the increasing dependence of the British economy upon international trade and, more important, international finance. By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, exports composed as much as one-fifth of total national income,31 a far higher proportion than in Walpole’s or Pitt’s time; for the enormous cotton-textile industry in particular, overseas markets were vital. But foreign imports, both of raw materials and (increasingly) of foodstuffs, were also becoming vital as Britain moved from being a predominantly agricultural to being a predominantly urban/industrial society. And in the fastest-growing sector of all, the “invisible” services of banking, insurance, commodity-dealing, and overseas investment, the reliance upon a world market was even more critical. The world was the City of London’s oyster, which was all very well in peacetime; but what would the situation be if ever it came to another Great Power war? Would Britain’s export markets be even more badly affected than in 1809 and 1811–1812? Was not the entire economy, and domestic population, becoming too dependent upon imported goods, which might easily be cut off or suspended in periods of conflict? And would not the London-based global banking and financial system collapse at the onset of another world war, since the markets might be closed, insurances suspended, international capital transfers retarded, and credit ruined? In such circumstances, ironically, the advanced British economy might be more severely hurt than a state which was less “mature” but also less dependent upon international trade and finance.

另一个潜在的战略性弱点在于英国的经济日益依赖国际贸易,尤其是国际金融。到了19世纪中叶的几十年,各项出口构成了多达1/5的国家总收入,这个比率远比沃波尔时代和小皮特时代高;特别是对庞大的棉纺织业来说,海外市场是必不可少的。但是随着英国从主要是农业的社会转向主要是城市—工业的社会,国外的进口,不论是原料还是(日益增加的)食品,都变得极其重要。在发展最快的部门——银行、保险、商品交易和海外投资等“无形”的服务业中,对世界市场的依赖尤为关键。世界是伦敦城的囊中物,在和平时期一切顺利;但如果发生另一场大国战争,局势又会怎么样呢?英国的出口市场是否会受到甚至比1809年和1811~1812年更为严重的影响?它的整个经济和国内的人口是否会变得过于依赖在冲突时期容易被切断或停止供应的进口商品?在另一次世界大战的冲击中,由于市场关闭,保险停止,国际资本的转移受阻,信贷业务被破坏,以伦敦为基地的全球银行和金融体制是否会崩溃?具有讽刺意义的是,在这些情况下,先进的英国经济可能比一个不那么“成熟”但也较少依赖国际贸易和金融的国家,更会受到严重的伤害。

Given the Liberal assumptions about interstate harmony and constantly increasing prosperity, these seemed idle fears; all that was required was for statesmen to act rationally and to avoid the ancient folly of quarreling with other peoples. And, indeed, the laissez-faire Liberals argued, the more British industry and commerce became integrated with, and dependent upon, the global economy, the greater would be the disincentive to pursue policies which might lead to conflict. In the same way, the growth of the financial sector was to be welcomed, since it was not only fueling the midcentury “boom,” but demonstrating how advanced and progressive Britain had become; even if other countries followed her lead and did industrialize, she could switch her efforts to servicing that development, and gaining even more profits thereby. In Bernard Porter’s words, she was the first frogspawn egg to grow legs, the first tadpole to change into a frog, the first frog to hop out of the pond. She was economically different from the others, but that was only because she was so far ahead of them. 32 Given these auspicious circumstances, fears of strategical weakness appeared groundless; and most mid-Victorians preferred, like Kingsley as he cried tears of pride during the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851, to believe that a cosmic destiny was at work:

由于自由主义者提出的关于国际和谐和持续地欣欣向荣的主张,以上这些似乎是杞人忧天。他们认为英国最需要的是,政治家们理智行事,避免去干预其他民族争吵的蠢事。主张放任主义的自由主义者甚至争辩说,英国的工商业越是被纳入全球经济并依赖它,对采用可能会导致冲突的政策的抑制力就越大。同样,金融部门的发展会受到欢迎,因为它不但为19世纪中期的“繁荣”添加燃料,而且也显示出英国已变得多么先进和进步;即使其他国家仿效它,并且的确工业化了,它也能把它的力量转到为这种发展进行服务方面,由此甚至能获取更多的利润。用伯纳德·波特的话来说,它是第一个长出腿的青蛙卵,第一个变成青蛙的蝌蚪,第一个跳出池塘的青蛙。它在经济上与众不同,但这只是因为它遥遥领先于其他国家。由于这些繁荣昌盛的形势,对战略性弱点的担心似乎是没有根据的。就像1851年在水晶宫举办万国博览会期间噙着骄傲的泪水高呼的金斯利一样,大部分维多利亚时代中期的人们宁愿相信,一切可以顺应天命:

The spinning jenny and the railroad, Cunard’s liners and the electric telegraph, are to me … signs that we are, on some points at least, in harmony with the universe; that there is a mighty spirit working among us … the Ordering and Creating God. 33

珍妮纺纱机及铁路、康纳德的轮船和电报对我来说……在某些方面,至少是我们与宇宙和谐相处的迹象;就像有一个威力无比的神……安排一切、创造一切的上帝在我们中间显示着征兆。

Like all other civilizations at the top of the wheel of fortune, therefore, the British could believe that their position was both “natural” and destined to continue. And just like all those other civilizations, they were in for a rude shock. But that was still some way into the future, and in the age of Palmerston and Macaulay, it was British strengths rather than weaknesses which were mostly in evidence.

因此,与在幸福之舟上的其他文明一样,英国人可以相信,他们的地位既是“天然”的,又命中注定会保持下去。也正像其他一切文明一样,他们准备承受突然的冲击。但这是相当长时期以后的事,在巴麦尊和麦考莱[8]时期,通常英国明显地表现出来的是它的力量,而不是它的弱点。