Ming China

一、明代中国

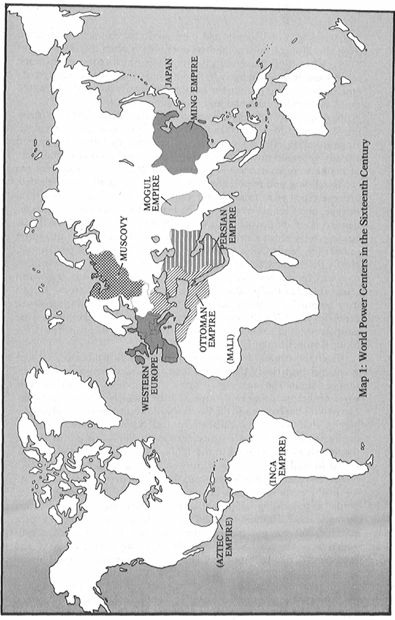

Of all the civilizations of premodern times, none appeared more advanced, none felt more superior, than that of China. 3 Its considerable population, 100–130 million compared with Europe’s 50–55 million in the fifteenth century; its remarkable culture; its exceedingly fertile and irrigated plains, linked by a splendid canal system since the eleventh century; and its unified, hierarchic administration run by a well-educated Confucian bureaucracy had given a coherence and sophistication to Chinese society which was the envy of foreign visitors. True, that civilization had been subjected to severe disruption from the Mongol hordes, and to domination after the invasions of Kublai Khan. But China had a habit of changing its conquerors much more than it was changed by them, and when the Ming dynasty emerged in 1368 to reunite the empire and finally defeat the Mongols, much of the old order and learning remained.

在近代以前时期的所有文明中,没有一个国家的文明比中国文明更发达,更先进。它有众多的人口(在15世纪有1亿~1.3亿人口,而欧洲当时只有5 000万~5 500万人),有灿烂的文化,有特别肥沃的土壤以及从11世纪起就由一个杰出的运河系统连结起来的、有灌溉之利的平原,并且有受到儒家良好教育的官吏治理的、统一的、等级制的行政机构,这些使中国社会富于经验,具有一种凝聚力,使外国来访者羡慕不已。的确,这个文明受到蒙古游牧部落的严重破坏,并且在忽必烈汗的入侵以后被蒙古人统治着。但是,中国惯于同化征服者而不是被后者同化,当1368年出现的明朝重新统一帝国并最后打败蒙古人的时候,许多旧的制度和知识都保留下来。

To readers brought up to respect “western” science, the most striking feature of Chinese civilization must be its technological precocity. Huge libraries existed from early on. Printing by movable type had already appeared in eleventh-century China, and soon large numbers of books were in existence. Trade and industry, stimulated by the canal-building and population pressures, were equally sophisticated. Chinese cities were much larger than their equivalents in medieval Europe, and Chinese trade routes as extensive. Paper money had earlier expedited the flow of commerce and the growth of markets. By the later decades of the eleventh century there existed an enormous iron industry in north China, producing around 125,000 tons per annum, chiefly for military and governmental use—the army of over a million men was, for example, an enormous market for iron goods. It is worth remarking that this production figure was far larger than the British iron output in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, seven centuries later! The Chinese were also probably the first to invent true gunpowder; and cannons were used by the Ming to overthrow their Mongol rulers in the late fourteenth century.

对于受教尊重“西方”科学的读者来说,中国文明最引人注目的特点必定是其技术上的早熟。中国11世纪就出现了活字印刷,不久就有大量书籍。商业和工业受到开凿运河和人口压力的促进,同样很发达。中国的城市要比中世纪欧洲的城市大得多,商路也四通八达。纸币较早地加速了商业的流通和市场的发展。到11世纪末,中国北部已有可观的冶铁业,每年能生产大约12.5万吨铁,主要为军队和政府所用,比如,100万人以上的军队是铁制品的一个巨大市场。值得指出的是,这一生产数字要比700年以后英国工业革命早期的铁产量还多!中国也许是第一个发明真正火药的国家,而且在14世纪末明朝人曾用大炮推翻蒙古人的统治。

Given this evidence of cultural and technological advance, it is also not surprising to learn that the Chinese had turned to overseas exploration and trade. The magnetic compass was another Chinese invention, some of their junks were as large as later Spanish galleons, and commerce with the Indies and the Pacific islands was potentially as profitable as that along the caravan routes. Naval warfare had been conducted on the Yangtze many decades earlier—in order to subdue the vessels of Sung China in the 1260s, Kublai Khan had been compelled to build his own great fleet of fighting ships, equipped with projectile-throwing machines—and the coastal grain trade was booming in the early fourteenth century. In 1420, the Ming navy was recorded as possessing 1,350 combat vessels, including 400 large floating fortresses and 250 ships designed for long-range cruising. Such a force eclipsed, but did not include, the many privately managed vessels which were already trading with Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia, and even East Africa by that time, and bringing revenue to the Chinese state, which sought to tax this maritime commerce.

对中国文化和技术进步有了这些了解以后,再听到中国人已转向海外开发和贸易也就不足为奇了。指南针是中国人的另一发明,他们有些平底帆船同后来西班牙的大帆船一样大,而与印度和太平洋诸岛的贸易,从潜力上说与往返大漠商路的贸易一样有利可图。许多年以前中国人就在长江进行过水战。13世纪60年代,为了征服宋朝的船队,忽必烈汗强迫建造他自己的大战船队,装备发射投掷机械。14世纪初期,沿海谷物贸易兴旺发达。据记载,1420年明朝的海军拥有1 350艘战船,其中包括400个大型浮动堡垒和250艘设计用于远洋航行的船舶。这样一支力量还不包括许多私人经营的船舶,但后者同海军比起来显得黯然失色。这些私人经营的船只那时已经在与朝鲜、日本、东南亚,甚至东非进行贸易,并为中国国家带来收入,因为国家试图对这种海上贸易征收捐税。

The most famous of the official overseas expeditions were the seven long-distance cruises undertaken by the admiral Cheng Ho between 1405 and 1433. Consisting on occasions of hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men, these fleets visited ports from Malacca and Ceylon to the Red Sea entrances and Zanzibar. Bestowing gifts upon deferential local rulers on the one hand, they compelled the recalcitrant to acknowledge Peking on the other. One ship returned with giraffes from East Africa to entertain the Chinese emperor; another with a Ceylonese chief who had been unwise enough not to acknowledge the supremacy of the Son of Heaven. (It must be noted, however, that the Chinese apparently never plundered nor murdered —unlike the Portuguese, Dutch, and other European invaders of the Indian Ocean. ) From what historians and archaeologists can tell us of the size, power, and seaworthiness of Cheng Ho’s navy—some of the great treasure ships appear to have been around 400 feet long and displaced over 1,500 tons—they might well have been able to sail around Africa and “discover” Portugal several decades before Henry the Navigator’s expeditions began earnestly to push south of Ceuta.

最有名的官方海上远征,是1405年和1433年间海军将领郑和进行的七次远洋航行。这支船队有时由数百艘船舶和数万人组成,遍访从马六甲和锡兰到红海口和桑给巴尔的各个港口。一方面他们向顺从的地方统治者馈赠礼品,另一方面强迫桀骜不驯的统治者承认北京的朝廷。曾有一艘船带着长颈鹿从东非返回,以取悦中国皇帝;另一艘船带回了一个锡兰首领,因他极不明智,竟不承认天子的最高权力(但是应当指出,中国人从不曾抢劫和杀戮,这与葡萄牙人、荷兰人和其他入侵印度洋的欧洲人不同)。从历史学家和考古学家可以告诉我们的关于郑和船队的规模、实力和适航性(有些大宝船看来大约有400英尺长和1 500吨以上的排水量)来看,他们或许在航海家亨利的探险开始热心地向休达[2]以南推进之前好几十年,就可以绕过非洲并“发现”葡萄牙。

But the Chinese expedition of 1433 was the last of the line, and three years later an imperial edict banned the construction of seagoing ships; later still, a specific order forbade the existence of ships with more than two masts. Naval personnel would henceforth be employed on smaller vessels on the Grand Canal. Cheng Ho’s great warships were laid up and rotted away. Despite all the opportunities which beckoned overseas, China had decided to turn its back on the world.

但1433年中国的远征是这条航线的最后一次,3年以后一项皇帝诏书禁止建造海船,再以后一项专门敕令竟禁止保存两桅以上的船舶。此后船队船员受雇于大运河的小船。郑和的大战船被搁置朽烂。尽管有种种机会向海外召唤,但中国还是决定转过身去背对世界。

There was, to be sure, a plausible strategical reason for this decision. The northern frontiers of the empire were again under some pressure from the Mongols, and it may have seemed prudent to concentrate military resources in this more vulnerable area. Under such circumstances a large navy was an expensive luxury, and in any case, the attempted Chinese expansion southward into Annam (Vietnam) was proving fruitless and costly. Yet this quite valid reasoning does not appear to have been reconsidered when the disadvantages of naval retrenchment later became clear: within a century or so, the Chinese coastline and even cities on the Yangtze were being attacked by Japanese pirates, but there was no serious rebuilding of an imperial navy. Even the repeated appearance of Portuguese vessels off the China coast did not force a reassessment. * Defense on land was all that was required, the mandarins reasoned, for had not all maritime trade by Chinese subjects been forbidden in any case?

诚然,这项决定有一种似乎有理的战略原因。帝国北部边疆再次遭受蒙古人的威胁,把军事资源集中到这个比较脆弱的地区或许是谨慎的。在这种情况下,一支强大的海军是一种耗资巨大的奢侈,无论如何,中国尝试过的南下向安南(越南)的扩张被证明是徒劳的,而且代价很高。但当后来收缩海军的弊端已经显露出来以后,看来仍未重新考虑过这个颇为有理的论据。在大约一个世纪的时间内,中国沿海,甚至长江沿岸的城市不断遭到日本海盗的袭击,但没有认真重建帝国海军[3]。甚至葡萄牙船队在中国沿海的反复出没也未能使当局重新估计局势。达官贵人们推理说,陆上防御就够了,因为不管怎么说,中国臣民所进行的一切海上贸易不是都没有禁止吗?

Apart from the costs and other disincentives involved, therefore, a key element in China’s retreat was the sheer conservatism of the Confucian bureaucracy6—a conservatism heightened in the Ming period by resentment at the changes earlier forced upon them by the Mongols. In this “Restoration” atmosphere, the allimportant officialdom was concerned to preserve and recapture the past, not to create a brighter future based upon overseas expansion and commerce. According to the Confucian code, warfare itself was a deplorable activity and armed forces were made necessary only by the fear of barbarian attacks or internal revolts. The mandarins’ dislike of the army (and the navy) was accompanied by a suspicion of the trader. The accumulation of private capital, the practice of buying cheap and selling dear, the ostentation of the nouveau riche merchant, all offended the elite, scholarly bureaucrats—almost as much as they aroused the resentments of the toiling masses. While not wishing to bring the entire market economy to a halt, the mandarins often intervened against individual merchants by confiscating their property or banning their business. Foreign trade by Chinese subjects must have seemed even more dubious to mandarin eyes, simply because it was less under their control.

因此,除去新涉及的耗费和其他起抑制作用的因素外,中国倒退的关键因素纯粹是信奉孔子学说的官吏们的保守性,这一保守性在明朝时期因对蒙古人早先强加给他们的变化不满而加强了。在这种复辟气氛下,所有重要官吏都关心维护和恢复过去,而不是创造基于海外扩张和贸易的更光辉的未来。根据孔子学说的行为准则,战争是一种可悲的活动,而军队只有在担心发生蛮族入侵或内乱时才有必要。达官贵人对军队(和海军)的厌恶伴随着对商人的疑虑。私人资本的积累、贱买贵卖的做法、暴发户商人的铺张阔气,都冒犯了这些权贵士大夫,几乎如同他们激起了劳苦大众的不满一样。虽然达官贵人们并不想完全停止整个市场经济,但经常通过没收商人的财产或禁止他们经商来干涉个别商人。中国民间进行的对外贸易,在达官贵人们的眼里必定显得更加令人疑虑,这仅仅是因为外贸较少受他们控制。

This dislike of commerce and private capital does not conflict with the enormous technological achievements mentioned above. The Ming rebuilding of the Great Wall of China and the development of the canal system, the ironworks, and the imperial navy were for state purposes, because the bureaucracy had advised the emperor that they were necessary. But just as these enterprises could be started, so also could they be neglected. The canals were permitted to decay, the army was periodically starved of new equipment, the astronomical clocks (built c. 1090) were disregarded, the ironworks gradually fell into desuetude. These were not the only disincentives to economic growth. Printing was restricted to scholarly works and not employed for the widespread dissemination of practical knowledge, much less for social criticism. The use of paper currency was discontinued. Chinese cities were never allowed the autonomy of those in the West; there were no Chinese burghers, with all that that term implied; when the location of the emperor’s court was altered, the capital city had to move as well. Yet without official encouragement, merchants and other entrepreneurs could not thrive; and even those who did acquire wealth tended to spend it on land and education, rather than investing in protoindustrial development. Similarly, the banning of overseas trade and fishing took away another potential stimulus to sustained economic expansion; such foreign trade as did occur with the Portuguese and Dutch in the following centuries was in luxury goods and (although there were doubtless many evasions) controlled by officials.

对商业和私人资本的厌恶与上述大量技术成就并不冲突。明朝重建了中国万里长城,发展了运河系统、制铁业和御用帝国海军,因为官吏们上奏皇帝说,这些都是必须的。但这些事业才刚刚开始就受到忽视。运河听任淤塞,军队经常缺乏新的装备,天文仪器(约建于1090年)缺乏管理,铁工场被废弃。这些不仅仅对经济发展起到阻碍作用。印刷仅限于学术著作,没有用于广泛传播实际知识,更很少用于社会批评。纸币的使用被中止。中国城市从来也不容许西方城市所享有的自治;没有真正意义的中国自治市民;一旦皇宫迁址,帝都亦随之迁移。然而得不到官方的鼓励,商人和其他企业家就不能兴旺起来。即使那些发了财的人也宁可把钱用于购置土地和兴办教育,而不情愿投资发展基础工业。同样,禁止海外贸易和海洋渔业,更消除了刺激经济持续发展的另一潜在因素。尽管在以后几个世纪里,受官方控制的(虽然无疑会有许多逃避监督的)与葡萄牙人和荷兰人的奢侈品贸易之类的对外贸易还是存在。

In consequence, Ming China was a much less vigorous and enterprising land than it had been under the Sung dynasty four centuries earlier. There were improved agricultural techniques in the Ming period, to be sure, but after a while even this more intensive farming and the use of marginal lands found it harder to keep pace with the burgeoning population; and the latter was only to be checked by those Malthusian instruments of plague, floods, and war, all of which were very difficult to handle. Even the replacement of the Mings by the more vigorous Manchus after 1644 could not halt the steady relative decline.

结果,明王朝时期的中国与400年前的宋王朝比起来,活力和进取精神都大为逊色。明朝时期农业技术的确有所改进,但即使这种比较集约化的农业和对边沿土地的开发利用也很难跟上人口增长的步伐;中国的人口增长仅仅受到马尔萨斯所说的瘟疫、洪水、战争等方式的制约,而这些灾害是很难预测的。甚至1644年以后满人取代明朝也未能停止这种持续的相对衰落。

One final detail can summarize this tale. In 1736—just as Abraham Darby’s ironworks at Coalbrookdale were beginning to boom—the blast furnaces and coke ovens of Honan and Hopei were abandoned entirely. They had been great before the Conqueror had landed at Hastings. Now they would not resume production until the twentieth century.

一个最后的细节可以概括这段历史。1736年,即(英国)亚伯拉罕·达比在科尔布鲁克德尔的铁工场开始出名的时候,河南和河北的鼓风炉和炼焦炉已被完全废弃了。而这些炉子的规模在征服者于哈斯丁斯登陆[4]以前就已经很大了。这下子它们要等到20世纪才会重新恢复生产。