The Crimean War and the Erosion of Russian Power

克里米亚战争和俄国的衰落

Russia’s relative power was to decline the most during the post-1815 decades of international peace and industrialization—although that was not fully evident until the Crimean War (1854–1856) itself. In 1814 Europe had been awed as the Russian army advanced to the west, and the Paris crowds had prudently shouted “Vive l’empereur Alexandre!” as the czar entered their city behind his brigades of cossacks. The peace settlement itself, with its archconservative emphasis against future territorial and political change, was underwritten by a Russian army of 800,000 men—as far superior to any rivals on land as the Royal Navy was to other fleets at sea. Both Austria and Prussia were overshadowed by this eastern colossus, fearing its strength even as they proclaimed monarchical solidarity with it. If anything, Russia’s role as the gendarme of Europe increased when the messianic Alexander I was succeeded by the autocratic Nicholas I (1825–1855); and the latter’s position was further enhanced by the revolutionary events of 1848–1849, when, as Palmerston noted, Russia and Britain were the only powers that were “standing upright. ”58 The desperate appeals of the Habsburg government for aid in suppressing the Hungarian revolt were rewarded by the dispatch of three Russian armies. By contrast, the waverings of Frederick William IV of Prussia toward internal reform movements, together with the proposals for changes in the German Federation, provoked unrelenting Russian pressure until the court at Berlin accepted policies of domestic reaction and the diplomatic retreat at Oelmuetz. As for the “forces of change” themselves after 1848, all elements, whether defeated Polish and Hungarian nationalists, or frustrated bourgeois liberals, or Marxists, were agreed that the chief bulwark against progress in Europe would long remain the empire of the czars.

俄国的相对力量在1815年以后国际和平和工业化的大部分时期趋向衰落,虽然直到克里米亚战争时(1854~1856年)才完全地表现出来。在1814年,欧洲曾经慑服于俄军的西进。当沙皇随哥萨克旅进城时,巴黎的群众曾经谨慎地高呼“亚历山大皇帝万岁”。和平解决本身主要基于保守主义的考虑,重点在于反对未来的领土和政治变动。这种解决得到了一支80万人的俄国军队的保证——在陆地上这支军队远远胜过其他任何对手,就像在海上英国皇家海军胜过其他舰队一样。奥地利和普鲁士都被这个东方巨人所压倒,甚至当它们与俄国宣布君主团结时,也害怕它的实力。当专制的尼古拉一世(1825~1855年在位)继承了以救世主自居的亚历山大一世时,俄国作为欧洲宪兵的作用——如果有的话——扩大了。尼古拉一世的地位因1848~1849年的革命事件而进一步加强,当时只有俄国和英国像巴麦尊勋爵指出的那样是“傲然挺立”的强国。奥地利当局要求援助去镇压匈牙利叛乱的紧急呼吁,得到了俄国派出三个军的回应。相比之下,普鲁士的腓特烈·威廉对国内改革运动的动摇,再加上要求改变德意志邦联的各种建议,激起了俄国持续的压力,直到柏林宫廷接受在国内实行反动政策和在奥尔米茨做出外交让步时为止。至于1848年以后的“变革势力”本身,所有的人(不论是被打败的波兰和匈牙利民族主义者,还是灰心丧气的资产阶级自由主义者,或是马克思主义者)都认为,反对欧洲进步的主要壁垒,长期以来一直是沙皇的帝国。

Yet at the economic and technological level, Russia was losing ground in an alarming way between 1815 and 1880, at least relative to other powers. This is not to say that there was no economic improvement, even under Nicholas I, many of whose officials had been hostile to market forces or to any signs of modernization. The population grew rapidly (from 51 million in 1816, to 76 million in 1860, to 100 million in 1880), and that of the towns grew the fastest of all. Iron production increased, and the textile industry multiplied in size. Between 1804 and 1860, it was claimed, the number of factories or industrial enterprises rose from 2,400 to over 15,000. Steam engines and modern machinery were imported from the west; and from the 1830s onward a railway network began to emerge. The very fact that historians have quarreled over whether an “industrial revolution” occurred in Russia during these decades confirms that things were on the move. 59

可是,在1815~1880年,俄国在经济和技术方面正在惊人地衰弱下去,至少在与其他强国相比时是如此。这并不是说它的经济没有增进,虽然在尼古拉一世时期,他的许多官员一直对市场力量或对任何现代化的迹象抱敌对态度。它的人口迅速增加(从1816年的5100万,增至1860年的7600万,又增至1880年的l亿人),而城镇的人口增长得最快。铁产量增加了,纺织业的规模成倍扩大。据称,在1804~1860年,工厂或工业企业从2400个增至15000个。蒸汽机和现代机械从西方输入。从19世纪30年代起,一个铁路网开始形成。历史学家曾就这几十年中俄国是否发生“工业革命”的问题争论不休,这件事本身就证明事物在发展之中。

But the blunt point was that the rest of Europe was moving far faster and that Russia was losing ground. Because of its far bigger population, it had easily possessed the largest total GNP in the early nineteenth century. Two generations later, that was no longer the case, as shown in Table 9.

但是,确凿的事实是,欧洲的其余部分发展得更快,俄国正在衰落。由于更为众多的人口,在19世纪初叶,它曾不费劲地拥有最大的国民生产值。两代人以后,情况再也不是这样,这从表9可以看出。

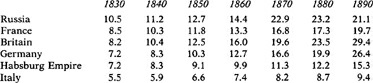

Table 9. GNP of the European Great Powers, 1830–189060

表9 欧洲列强的国民生产总值(1830~1890年)

(at market prices, in 1960 U. S. dollars and prices; in billions)

(以1960年美元和物价的市场价格为标准;单位:10亿美元)

But these figures were even more alarming when the per capita amount of GNP is studied (see Table 10).

但是,当研究了国民生产总值的人均产值,这些数字更令人吃惊(见表10)。

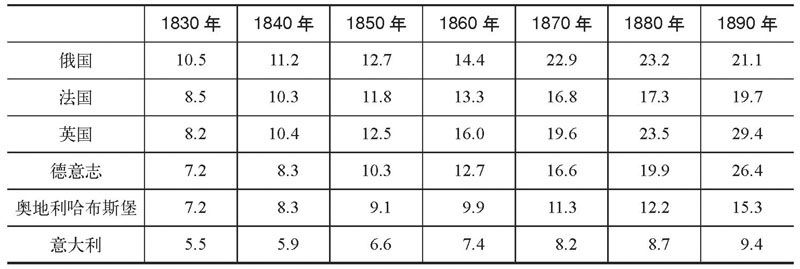

Table 10. Per Capita GNP of the European Great Powers, 1830–189061

表10 欧洲列强国民生产总值的人均产值(1830~1890年)

(in 1960 U.S. dollars and prices)

(以1960年美元和价格为标准;单位:美元)

The figures show that the increase in Russia’s total GNP which occurred during these years was overwhelmingly due to the rise in its population, whether by births or by conquests in Turkestan and elsewhere, and had little to do with real increases in productivity (especially industrial productivity). Russia’s per capita income, and national product, had always been behind that of western Europe; but it now fell even further behind, from (for example) one-half of Britain’s per capita income in 1830 to one-quarter of that figure sixty years later.

数字表明,这些年俄国国民生产值总数增加的最大原因,是它人口的增长(不论是通过生育,还是通过在土耳其斯坦和其他地方的征服),而与产量(特别是工业产量)的实际增长无关。俄国的人均收入和国民产值一直落在西欧后面,这时差距甚至越来越大了,例如,1830年是英国人均收入的一半,60年以后只是英国的l/4。

In the same way, the doubling of Russia’s iron production in the early nineteenth century compared badly with Britain’s thirtyfold increase;62 within two generations, Russia had changed from being Europe’s largest producer and exporter of iron into a country increasingly dependent upon imports of western manufactures. Even the improvements in rail and steamship communications need to be put in perspective. By 1850 Russia had little over 500 miles of railroad, compared with the United States’ 8,500 miles; and much of the increase in steamship trade, on the great rivers or out of the Baltic and Black seas, revolved around the carriage of grains needed for the burgeoning home population and to pay for imported manufactured goods by the dispatch of wheat to Britain. What new developments occurred were all too frequently in the hands of foreign merchants and entrepreneurs (the export trade certainly was), and turned Russia ever more into a supplier of primary materials for advanced economies. On closer examination of the evidence, it appears that most of the new “factories” and “industrial enterprises” employed fewer than sixteen people, and were scarcely mechanized at all. A general lack of capital, low consumer demand, a minuscule middle class, vast distances and extreme climates, and the heavy hand of an autocratic, suspicious state made the prospects for industrial “takeoff” in Russia more difficult than in virtually anywhere else in Europe. 63

同样,在19世纪初期,俄国铁的产量翻了一番,但这与英国30倍的增长率相比是微不足道的;在两代人的时间内,俄国已从最大的铁生产国和出口国,变成日益依赖进口西方制成品的国家。甚至铁路和轮船运输的进步也需加剖析。到1850年,俄国拥有略多于500英里的铁路,而美国则有8500英里。在大河流或黑海和波罗的海进行的轮船贸易的大部分增长,则是为了运输国内大量增加的人口所需要的粮食和向英国运输小麦以偿付进口的制成品。出现的一切新发展往往掌握在外国商人和企业家手中(出口贸易肯定是这样),这使俄国越来越成为经济发达国家的原料供应国。经过对材料的周密考察就可以看出,大部分新“工厂”和“工业企业”雇用的人都不足16个,而且它们大概根本没有机械化。资本的普遍缺乏、消费者的低需求、弱小的中产阶级、遥远的距离和严酷的气候、专制和多疑国家的高压手段,使俄国工业“起飞”的前景实际上比欧洲任何地方都难以实现。

For a long while, these ominous economic trends did not translate into a noticeable Russian military weakness. On the contrary, the post-1815 preference shown by the Great Powers for ancien régime structures in general could nowhere be more clearly seen than in the social composition, weaponry, and tactics of their armies. Still in the shadows cast by the French Revolution, governments were more concerned about the political and social reliability of their armed forces than about military reforms; and the generals themselves, no longer facing the test of a great war, emphasized hierarchy, obedience, and caution—traits reinforced by Nicholas I’s obsession with formal parades and grand marches. Given these general circumstances, the sheer size of the Russian army and the steadiness of its mass conscripts appeared more impressive to outside observers than such arcane matters as military logistics or the general level of education among the officer corps. What was more, the Russian army was active and often successful in its frequent campaigns of expansion into the Caucasus and across Turkestan—thrusts which were already beginning to worry the British in India, and to make Anglo-Russian relations in the nineteenth century much more strained than they had been in the eighteenth. 64 Equally impressive to outside eyes was the Russian suppression of the Hungarian rebellion of 1848–1849, and the czar’s claim that he stood ready to dispatch 400,000 troops to quell the contemporaneous revolt in Paris. What those observers failed to note was the less imposing fact that the greater part of the Russian army was always pinned down by internal garrison duties, by “police” actions in Poland and the Ukraine, and by other activities, such as border patrols and the Military Colonies; and that what was left was not particularly efficient—of the 11,000 casualties incurred in the Hungarian campaign, for example, all but 1,000 were caused by diseases, because of the inefficiency of the army’s logistical and medical services. 65

在很长时期,这些不祥的经济趋势并没有转变为显著的俄国军事弱点。相反,1815年以后大国普遍表现出的对旧制度结构的偏爱,在它们军队的社会成分、武器和战术中看得更为清楚。各国政府仍处于法国革命的阴影之中,关心它们军队的政治和社会的可靠性更甚于军事改革。不再面临大战争考验的将军们自己很注意等级、服从和谨慎——这些特征更因尼古拉一世迷恋讲究形式的检阅和大行军而突出。由于这些总的情况,俄国军队单纯的规模和它大量征兵的稳定性,对国外的观察家来说,比诸如军事后勤和军官团教育水平等不显眼的事务更能给人以深刻的印象。更有甚者,俄国的军队过去是有战斗力的,常常在频繁的深入高加索和跨越土耳其的扩张战役中取胜,这些挺进已经开始使印度的英国人不安,并使19世纪的英俄关系比18世纪时的两国关系更加紧张。对外国人来说,同样引人注目的是俄国对1848~1849年匈牙利叛乱的镇压和沙皇的主张,即他随时准备派40万大军去平息同时代的巴黎叛乱。但那些观察家们却没有注意到一个较不显眼的事实:俄国的大部分军队总是受制于国内的驻防任务、在波兰和芬兰的“警察”行动,以及诸如边境巡逻和军事殖民等其他活动而不能动弹;所剩下的部队并不是特别有战斗力的,例如,在匈牙利之役遭受的伤亡中,除1000人外,其余人的死亡全是由疾病引起的,因为军队的后勤和医药供应工作毫无效率可言。

The campaigning in the Crimea from 1854 until 1855 provided an all too shocking confirmation of Russia’s backwardness. Czarist forces could not be concentrated. Allied operations in the Baltic (while never very serious), together with the threat of Swedish intervention, pinned down as many as 200,000 Russian troops in the north. The early campaigning in the Danubian principalities, and the far greater danger that Austria would turn its threats of intervention into reality, posed a danger to Bessarabia, the western Ukraine, and Russian Poland. The fighting against the Turks in the Caucasus placed immense demands upon both troops and supply systems, as did the defense of Russian territories in the Far East. 66 When the Anglo-French assault on the Crimea brought the war to a highly sensitive region of Russian territory, the armed forces of the czar were incapable of repudiating such an invasion.

1854~1855年的克里米亚之战,非常惊人地证实了俄国的落后。沙皇的部队不能集结。联军在波罗的海的行动(虽然一直不很严重),再加上瑞典干涉的威胁,把多达20万人的俄军牵制在北方。在多瑙河诸公国的早期征战,以及奥地利将干涉的威胁转为现实这一极为严重的危险,对比萨拉比亚、西乌克兰和俄属波兰构成了威胁。在高加索与土耳其人的交战,就像防卫远东的俄国领土一样,对部队和供应体系提出了迫切的要求。当英法军队对克里米亚的攻击把战争转到俄国领土的高敏感区域时,沙皇的武装部队没有能力把这种入侵拒之门外。

At sea, Russia possessed a fair-sized navy, with competent admirals, and it was able to destroy completely the weaker Turkish fleet at Sinope in November 1853; but as soon as the Anglo-French fleets entered the fray, the positions were reversed. 67 Many Russian vessels were fir-built and unseaworthy, their firepower was inadequate, and their crews were half-trained. The allies had many more steamdriven warships, some of them armed with shrapnel shells and Congreve rockets. Above all, Russia’s enemies had the industrial capacity to build newer vessels (including dozens of steam-driven gunboats), so that their advantage became greater as the war lengthened.

在海上,俄国拥有一支由干练的海军将领指挥的相当规模的海军。1853年11月,它能在锡诺普彻底摧毁较弱的土耳其舰队;但是一旦英法舰队参战,形势立刻逆转。许多俄国船只是用冷杉建造的,经不起风浪;它们的火力不足,船员未经充分的训练。联军拥有更为众多的蒸汽战舰,其中有的配备了榴霰弹和康格里夫火箭。尤其是,俄国的敌人有建造更新的船只(包括几十艘蒸汽炮舰)的工业能力,因此,随着战期的延长,他们的优势就变得更大了。

But the Russian army was even worse off. The ordinary infantryman fought well, and, under the inspired leadership of Admiral Nakhimov and the engineering genius of Colonel Todtleben, Russia’s prolonged defense of Sevastopol was a remarkable feat. But in all other respects the army was woefully inadequate. The cavalry regiments were unadventurous and their parade-ground horses incapable of strenuous campaigning (here the irregular cossack forces were better). Worse still, the Russian soldiers were wretchedly armed. Their old-fashioned flintlock muskets had a range of 200 yards, whereas the rifles of the Allied troops could fire effectively up to 1,000 yards; thus Russian casualties were far heavier.

但是,俄国陆军的处境更糟。一般的步兵打得不错,在纳希莫夫海军上将和工程天才托德尔本上校的鼓舞人心的领导下,俄国在塞瓦斯托波尔的长期防御是一个了不起的业绩。但在其他方面,陆军可悲地不能胜任其任务。骑兵团不敢冒险,他们练兵场上的马匹不能投入艰苦的战斗(在这方面,非正规的哥萨克部队要更好一些)。更糟的是,俄国士兵的武器非常差。他们老式的燧发滑膛枪的射程为200码,而联军的步枪能够有效地射至1000码;这样,俄国的伤亡人数要大得多。

Worst of all, even when the hugeness of the task was known, the Russian system as a whole was incapable of responding to it. Army leadership was poor, ridden with personal rivalries, and never able to produce a coherent grand strategy—here it simply reflected the general incompetence of the czar’s government. There were very few trained and educated officers of the middle rank, such as the Prussian army possessed in abundance, and initiative was totally frowned upon. Astonishingly, there were also very few reservists to call up in the event of a national emergency, since the adoption of a mass short-service system would have involved the demise of serfdom. * One consequence of this system was that Russia’s long-service army included many over-aged troopers; another even more fatal consequence was that some 400,000 of the new recruits hastily enrolled at the beginning of the war were totally untrained—for there were insufficient officers to do the job—and the withdrawal of that many men from the serf labor market hurt the Russian economy.

最坏的是,甚至当知道了任务的艰巨时,俄国的体制作为一个整体,仍不能对它做出反应。陆军的领导很差,充满了个人倾轧,始终未能产生一个有凝聚力的宏伟战略——在这方面,完全反映了沙皇政府普遍的无能。受过训练和教育的中级军官很少,而普鲁士军队中却有大批这样的军官;主动性会遭白眼。令人惊讶的是,在全国性的紧急状态下,可以征召的后备军却很少,因为短期服役制的大规模采用,将会导致农奴制的垮台[10]。实行这个制度的一个后果是,俄国长期服役的军队包括许多超龄的士兵;另一个更加致命的后果是,约40万在战争开始时匆忙入伍的新兵完全没有受过训练(因为没有足够的军官担任这项工作),而且从农奴市场抽出那么多人,损害了俄国的经济。

Finally, there were the logistical and economic weaknesses. Since there were no railways south of Moscow (!), the horse-drawn supply wagons had to cross hundreds of miles of steppes, which were a sea of mud during the spring thaw and the autumn rains. Furthermore, the horses themselves required so much fodder (which in turn had to be carried by other packhorses, and so on) that an enormous logistical effort produced disproportionately small results: allied troops and reinforcements could be sent from France and England by sea to the Crimea in three weeks, whereas Russian troops from Moscow sometimes took three months to reach the front. More alarming still was the collapse of the Russian army’s equipment stocks. “At the beginning of the war 1 million guns had been stockpiled; [at the end of 1855] only 90,000 were left. Of the 1,656 field guns, only 253 were available. … Stocks of powder and shot were in even worse shape. ”68 The longer the war lasted, the greater the allied superiority became, while the British blockade stifled the importation of new weapons.

最后,存在着后勤和经济方面的弱点。由于在莫斯科南部没有铁路,马拉的供应车不得不穿过数百英里的干草原,那里在春季解冻和秋季下雨时是一片泥泞的海洋。况且马匹本身也需要许多饲料(饲料又必须由驮马来运送),以致巨大的后勤努力所产生的效果小得不成比率。通过海路,联军在3个星期内可以把增援部队从法国和英格兰调到克里米亚,而来自莫斯科的俄国部队有时则要花3个月时间才能到达前线。更令人震惊的是俄军装备库存的枯竭。“在战争开始时贮存了100万件枪炮;到1855年末,只剩下了9万件。在1656门野战炮中,只有253门可用……火药和子弹的库存情况甚至更糟。”战争的时间拖得越长,联军的优势变得越大,同时英国人的封锁阻止了俄国对新武器的进口。

But the blockade did more than that: it cut off Russia’s flow of grain and other exports (except for those going overland to Prussia) and made it impossible for the Russian government to pay for the war other than by heavy borrowing. Military expenditures, which even in peacetime took four-fifths of the state revenue, rose from about 220 million rubles in 1853 to about 500 million in both war years 1854 and 1855. To cover part of the alarming deficit, the Russian treasury borrowed in Berlin and Amsterdam, but then the ruble’s international value tumbled; to cover the rest, it resorted to printing paper money, which led to large-scale price inflation and increasing peasant unrest. The earlier, brave attempts of the finance ministry to create a silver-based ruble and to ban all promissory notes—which had been the ruination of “sound finance” during the Napoleonic War and the campaigns against Persia, Turkey, and the Polish rebels—were now completely wrecked by the war in the Crimea. If Russia persisted in its fruitless struggle, the Crown Council was warned on January 15,1856, the state would go bankrupt. 69 Negotiations with the Great Powers offered the only way to avoid catastrophe.

但是,封锁的效果还不只此,它切断了俄国粮食和其他出口品的流通(除了从陆路把这些物品运往普鲁士),并使俄国政府不借巨额贷款就不能支付战争费用。甚至在和平时期就占这个国家岁入4/5的军费,从1853年的2.2亿卢布,增至1854年和1855年的5亿卢布左右。为了弥补惊人的亏空,俄国财政部在柏林和阿姆斯特丹借债,但那时卢布的国际币值下跌了;为了弥补剩余的不足数,它采用了印钞票的办法,这样就导致价格的猛烈上涨和日益增多的农民动乱。在此以前,财政部建立银本位卢布和取缔一切期票——它已在拿破仑战争和征讨波斯、土耳其和波兰造反者时破坏了“健全的财政”——的大胆的尝试,这时完全被克里米亚战争所破坏。1856年1月15日,国务会议被警告说,如果俄国坚持这场徒劳的斗争,国家将破产。与大国谈判是避免灾难的唯一出路。

All this is not to say that the allies found the Crimean War easy; for them, too, the campaigning involved strain and unpleasant shocks. The least badly affected, interestingly enough, was France, which for once benefited from being a hybrid power—it was less backward industrially and economically than Russia, and less “unmilitarized” than Britain. The armed forces sent eastward under General Saint- Arnaud were well equipped, well trained because of their North African operations, and reasonably experienced in overseas campaigning; their logistical and medicalsupport systems were as efficient as any which a midcentury administration could produce; and the French officers showed justified bemusement at their amateur British opposite numbers with their overloaded baggage. The French expeditionary force was by far the largest and made most of the major breakthroughs in the war. To some degree, then, the nation recovered its Napoleonic heritage in this fighting.

这一切并不是说,联军认为克里米亚战争是容易打的;对它们来说,这场战争也产生了紧张和不愉快的冲击。十分有趣的是,法国受到的不利影响最小,因为它在这一次得益于它是多种因素混合的强国——在工业和经济方面不像俄国那样落后,而在“非军事化”程度上则不如英国。在圣-阿尔诺将军率领下东进的武装部队,由于在北非打过仗,所以装备精良,训练有素,并且具有相当的海外征战的经验;他们的后勤和医药供应制度,与19世纪中期的政府能够提供的这种制度一样有效率。法国军官有理由对那些与他们地位相当的经验不足的英国军官带着超重行李的现象感到迷惑不解。法国远征军毫无疑问是最大的,并且在战争的重大突破中所做的贡献也最多。所以,在一定程度上法国在这次战斗中恢复了拿破仑时代的遗风。

By the later stages of the campaign, however, France was beginning to reveal signs of strain. Although it was a rich country, its government had to compete for ready funds with railway constructors and others seeking money from the Crédit Mobilier and other bankers. Gold was being drained away to the Crimea and Constantinople, sending up prices at home; and poor grain harvests didn’t help. Although the full war losses (100,000) were not known, early French enthusiasm for the conflict quickly evaporated. Popular riots over inflation reinforced the argument, widespread after the news of Sevastopol’s fall, that the war was being prolonged only for selfish and ambitious British purposes. 70 By that time, too, Napoleon III was eager to bring the fighting to an end: Russia had been chastised, France’s prestige had been boosted (and would rise further following a great international peace conference in Paris), and it was important not to get too distracted from German and Italian matters by escalating the conflict around the Black Sea. Even if he could not substantially redraw the map of Europe in 1856, Napoleon could certainly feel that France’s prospects were rosier than at any time since Waterloo. For another decade, the post-Crimean War fissures in the old Concert of Europe would allow that illusion to continue.

但是,到了战役的后面几个阶段,法国开始表现出一些紧张的迹象。虽然它是一个富国,但它的政府不得不与铁路建筑商等人向信用动产公司和其他银行家争夺现成的资金。黄金正在流向克里米亚和君士坦丁堡,造成了法国国内的物价上涨;歉收的粮食帮不了忙。虽然还不知道战争的全部损失(10万人),但法国人对这场冲突的早期热情很快就烟消云散。通货膨胀引起的民众骚乱,加剧了塞瓦斯托波尔陷落的消息传开后引起的争论,即正在延长的战争不过是迎合自私和有野心的英国的目的。到这个时候,拿破仑三世也急于要结束战斗:俄国已受到惩罚,法国的威信已经提高(在巴黎举行的一次重大的国际和平会议上还会进一步提高),而且重要的是,不能因为把黑海周围的冲突升级而过于分散对德意志和意大利事务的注意力。即使拿破仑三世不能在1856年对欧洲地图作重大的改变,他也肯定感到法国的前途比滑铁卢之战以来的任何时候都更加乐观。在旧欧洲协作体中,克里米亚战争后的分歧使这种幻想又继续了10年。

The British, by contrast, were far from satisfied with the Crimean War. Despite certain efforts at reform, the army was still in the Wellingtonian mold, and its commander, Raglan, had actually been Wellington’s military secretary in the Peninsular War. The cavalry was adequate—as cavalry forces go—but often misused (not just at Balaclava), and could scarcely be deployed in the Sevastopol siegeworks. While the soldiers were toughened old sweats who fought hard, the appalling lack of warm shelter in Crimean rains and winter, the incapacity of the army’s primitive medical services to handle large-scale outbreaks of dysentery and cholera, and the paucity of land transport caused needless losses and setbacks which infuriated the British nation. More embarrassing still, since the British army, like the Russian, was a long-service force chiefly useful for garrison duties, there was no trained reserve which could be drawn upon in wartime; but while the Russians could at least forcibly conscript hundreds of thousands of raw recruits, laissez-faire Britain could not, leaving the government in the embarrassing position of advertising for foreign mercenaries with which to fill the shortfall of troops in the Crimea. Yet while its army always remained a junior partner to the French, Britain’s navy had no real chance to secure a Nelsonic victory against a foe who prudently withdrew his fleet into fortified harbors. 71

对比之下,英国人则远远不满足于克里米亚战争。尽管作了某些改革的努力,陆军仍是威灵顿式的,而且它的统帅拉格伦男爵在半岛战争中实际上当过威灵顿的军事秘书。骑兵是胜任的(就骑兵部队而言),但常常被误用(不只是在巴拉克拉瓦战役),而且几乎不能部署在塞瓦斯托波尔的攻城设施中。虽然英军士兵是作战勇猛的健壮的老兵,但是在克里米亚雨季和冬季时保温掩体却惊人得缺乏,陆军中对付大规模出现的痢疾和霍乱的医疗工作原始而无能,陆路运输的不足,造成了激怒英国全国的不必要的损失和挫折。更加为难的是,由于英国陆军像俄国陆军一样,是主要用于卫戍任务的长期服役的部队,所以它没有在战时可资抽调的受过训练的后备力量;但俄国人至少还能够强制征召数十万新兵,而主张放任主义的英国却不能这么办,这就使政府处于进退两难的境地。它必须大肆宣传,广招外国的雇佣军,以弥补在克里米亚部队的缺额。可是,当英国的陆军一直处于法国的小伙伴地位时,它的海军却没有真正的机会去取得纳尔逊式的对敌作战的胜利,因为敌人谨慎地将其舰队撤入加固的港口内。

The explosion of public discontent in Britain at the London Times’ notorious revelations of military incompetence and of the sufferings of the sick and wounded troops can only be mentioned in passing here; it not only led to a change of ministry, but also provoked an earnest debate upon the difficulties inherent in being “a liberal state at war. ”72 More than that, the whole affair revealed that what had seemed to be Britain’s peculiar strengths—a low degree of government, a small imperial army, a heavy reliance upon sea power, an emphasis upon individual freedoms and an unfettered press, the powers of Parliament and of individual ministers—quite easily turned into weaknesses when the country was called upon to carry out an extensive military operation throughout all seasons against a major foe.

伦敦《泰晤士报》公开揭露了英国军事上的无能和部队伤病员的痛苦,公众对此爆发的不满情绪,这里只能附带一提:它不但导致内阁的改组,而且也激起了一场关于“一个战争中的自由国家”内在困难的认真争论。此外,整个事件表明,英国貌似特别强大之处(低程度的行政管理、少量的帝国陆军、对海上力量的严重依赖、对个人自由和不受约束的新闻界的重视、议会和个别大臣的权力)在全国被号召去对主要敌人进行一场一年到头的广泛的军事行动时,就很容易转化成弱点。

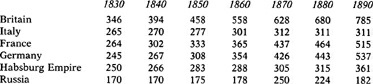

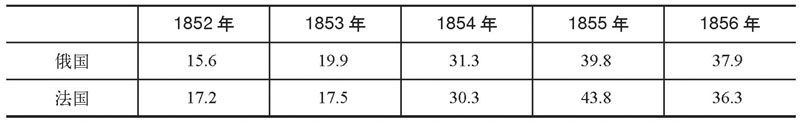

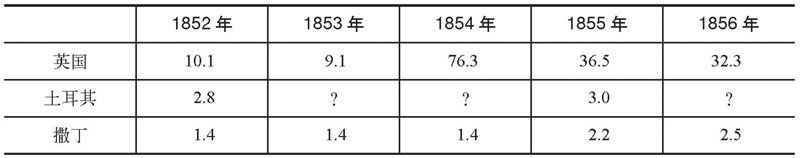

The British response to this test was (rather like the American response to wars in the twentieth century) to allocate vast amounts of money to the armed forces in order to make up for past neglect; and, once again, the crude figures of the military expenditures of the combatants go a long way toward explaining the eventual outcome of the conflict (see Table 11).

英国对这一考验的反应(很像20世纪美国人对战争的反应)是:为了弥补过去的疏忽,拨给武装部队大量资金。交战国的未经分类的军费数字(见表11),对说明冲突的最后结果是大有帮助的。

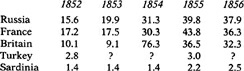

Table 11. Military Expenditures of the Powers in the Crimean War73

表11 克里米亚战争中列强的军费

(millions of pounds)

(单位:百万英镑)

But even when Britain bestirred itself, it could not swiftly create the proper instruments of power: military spending might multiply, hundreds of steam-driven vessels might be ordered, the expeditionary force might enjoy a surplus of tents and blankets and ammunition by 1855, and a belligerent Palmerston might assert the need to break up the Russian Empire; yet Britain’s small army could do little if France moved toward peace and Austria stayed neutral—which was precisely what happened in the months after the fall of Sevastopol. Only if the British nation and political economy became much more “militarized” could it sustain the war alone against Russia in any meaningful way; but the likely costs were far too high to a political leadership already made uneasy at the strategical, constitutional, and economic difficulties which the Crimean campaign had thrown up. 74 While feeling cheated of a proper victory, therefore, the British also were willing to compromise. What all this did was to make many Europeans (Frenchmen and Austrians as well as Russians) suspicious of London’s aims and reliability, just as it made the British public ever more disgusted at being entangled in continental affairs. While Napoleon’s France moved to the center of the European stage of 1856, therefore, Britain steadily moved to the edge—a drift which the Indian Mutiny (1857) and domestic reform movements could only intensify.

但甚至当英国自我激励时,它也不能迅速创造出足够的表现实力的物资。军费可能成倍增加,可能会订购数百艘蒸汽轮船,远征军到1855年可能会享受到过剩的帐篷、毛毯和弹药,好战的巴麦尊勋爵可能会强调打垮俄帝国的必要性。可是如果法国走向和平而奥地利保持中立(这正是塞瓦斯托波尔陷落后一个月内发生的事),英国的小型陆军是无所作为的。只有英国全国和它的政治经济变得更为“军事化”时,它才能郑重其事地坚持单独与俄国交战。但是,对一个已经因克里米亚之役造成的战略、宪法和经济方面的困难而感到不安的领导集团来说,可能代价实在太高了。因此,当感到受骗而不能取得应有的胜利时,英国人也愿意和解。这一切的结果使许多欧洲人(法国人、奥地利人还有俄国人)怀疑伦敦的目的和可靠性,正像它使英国公众越加讨厌卷入大陆的事务一样。当拿破仑的法国移向1856年的欧洲舞台中央时,英国则不断地靠边站——1857年的印度兵变和英国国内的改革运动,只会加剧这种转移趋势。

If the Crimean War had shocked the British, that was nothing compared to the blow which had been delivered to Russia’s power and self-esteem—not to mention the losses caused by the 480,000 deaths. “We cannot deceive ourselves any longer,” Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich flatly stated. “… we are both weaker and poorer than the first-class powers, and furthermore poorer not only in material but also in mental resources, especially in matters of administration. ”75 This knowledge drove the reformers in the Russian state toward a whole series of radical changes, most notably the abolition of serfdom. In addition, railway-building and industrialization were given far greater encouragement under Alexander II than under his father. Coal production, iron and steel production, large-scale utilities, and far bigger industrial enterprises were more in evidence from the 1860s onward, and the statistics provided in the economic histories of Russia are impressive enough at first sight. 76

如果说克里米亚战争冲击了英国人,那么这种冲击根本不能与俄国的实力和自尊心所受到的打击相比——更不必说48万人死亡所造成的损失了。康斯坦丁·尼古拉耶维奇大公直截了当地声称:“我们不能再欺骗自己了……我们比一流强国虚弱和贫穷,另外,我们不但在物质方面,而且在智力资源方面(尤其是管理方面)比它们贫乏。”这一醒悟推动了俄国的改革者进行了一系列激进的变革,最明显的是农奴制的废除。此外,在亚历山大二世时期,对铁路和工业化的鼓励远远大于他父亲统治的时期。煤和钢铁的产量、大规模的公用事业和规模大得多的工业企业,从19世纪60年代起更加引人注意了。俄国经济史提供的统计数字乍一看给人以很深刻的印象。

As ever, however, a change of perspective affects one’s judgment. Could this modernization keep pace with, let alone draw ahead of, the vast annual increases in the numbers of poor, uneducated peasants? Could it match the explosive increases in iron and steel production, and manufactures, taking place in the West Midlands, the Ruhr, Silesia, and Pittsburgh during the following two decades? Could it, even with its reorganized army, keep pace with the “military revolution” which the Prussians were about to reveal to the world, and which would emphasize again the qualitative over the quantitative elements of national strength? The answers to all those questions would disappoint a Russian nationalist, all too aware that his country’s place in Europe was substantially reduced from the position of eminence it had occupied in 1815 and 1848.

可是,像以往一样,现象的变化影响一个人的判断。这个现代化赶得上——且不说超过——贫困和无文化的农民人数每年的大量增长吗?在今后的20年中,它能与西方的英国中部、鲁尔、西里西亚和匹兹堡发生的钢铁和制成品生产的爆炸性增长相比吗?它能否赶上普鲁士即将向世界显示的、重视国家实力中质的因素超过重视量的因素的“军事革命”,甚至能否赶上经过现代化改造的普鲁士陆军?所有这些问题的答案将使一个俄国的民族主义者失望,他非常清楚,他的国家在欧洲的地位从1815年和1848年的突出位置大大地下降了。