The Position of the Powers, 1885–1914

大国的地位(1885~1914)

In the face of such unnervingly specific figures, that a certain power possessed 2. 7 percent of world manufacturing production in 1913, or that another had an industrial potential in 1928 which was only 45 percent of Britain’s in 1900, it is worth reemphasizing that all these statistics are abstract until placed within a specific historical and geopolitical context. Countries with virtually identical industrial output might nonetheless merit substantially different ratings in terms of Great Power effectiveness, because of such factors as the internal cohesion of the society in question, its ability to mobilize resources for state action, its geopolitical position, and its diplomatic capacities. Given the limitations of space, it will not be possible in this chapter to do for all the Great Powers what Correlli Barnett sought to do in his large-scale study of Britain some years ago. But what follows will try to remain close to Barnett’s larger framework, in which he argues that the power of a nation-state by no means consists only in its armed forces, but also in its economic and technological resources; in the dexterity, foresight and resolution with which its foreign policy is conducted; in the efficiency of its social and political organization. It consists most of all in the nation itself, the people; their skills, energy, ambition, discipline, initiative; their beliefs, myths and illusions. And it consists, further, in the way all these factors are related to one another. Moreover national power has to be considered not only in itself, in its absolute extent, but relative to the state’s foreign or imperial obligations; it has to be considered relative to the power of other states. 25

在这些令人不安的具体数字面前,即在1913年时某个大国只占世界制造业产量的2.7%,或者另一个大国在1928年其工业潜力只相当于英国1900年的45%,以下事实就值得再加强调:只有把这些统计数字放在特定的历史或地缘政治的背景下考察,它们才有实际意义。但是,由于诸如社会内部的凝聚力、大国为国家采取行动而动员资源的能力、它在地缘政治上的地位及其外交能力等因素,工业生产实际相同的国家在大国实力方面的分类仍有很大的不同。因篇幅所限,本章不可能像科雷里·巴尼特几年前对英国进行大规模研究时所做的那样,对各大国也进行那样规模的研究。但下面的论述将力图尽量地接近巴尼特的更大的框架,他对这种框架的描述是:

There is perhaps no better way of illustrating the diversity of grand-strategical effectiveness than by looking in the first instance at the three relative newcomers to the international system, Italy, Germany, and Japan. The first two had become united states only in 1870–1871; the third began to emerge from its self-imposed isolation after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. In all three societies there were impulses to emulate the established powers. By the 1880s and 1890s each was acquiring overseas territories; each, too, began to build a modern fleet to complement its standing army. Each was a significant element in the diplomatic calculus of the age and, at the latest by 1902, had become an alliance-partner to an older power. Yet all these similarities can hardly outweigh the fundamental differences in real strength which each possessed.

一个民族国家的力量并不仅仅存在于其武装部队,而且存在于其经济和技术资源,存在于用以指导其外交政策的灵活性、预见能力和果敢性,存在于其社会和政治机构的工作效率。最重要的是,国家力量存在于其国家本身,即存在于民族中;存在于他们的技术、能力、雄心、纪律、创造性中;存在于他们的信念、神话及其幻想中。进一步讲,还存在于这些因素相互联系的方式中。此外,在考虑国家力量时,不能只考虑它本身和它的绝对范围,还得顾及其国外的或帝国的义务,还得与其他国家的力量联系起来考虑。

要说明重大战略影响的多样性,最好的方法也许是看一看意大利、德国、日本这三个国际体系的较新成员的例子。前两个国家直到1870~1871年才成为统一的国家。日本直到1868年明治维新后,才开始从自我封闭的孤立状态中摆脱出来。在这三个社会中,都有与原有的大国进行竞争的动力。到19世纪80年代和90年代,每个国家都在获取海外领土,也已开始建立一支现代化的舰队补充自己的常备军。它们都是这一时期外交事务中的重要组成部分。最后,到1902年时,每个国家都已变成某个老牌大国的联盟伙伴。然而,所有这些相似之处都不能抵消每个国家拥有的实力上的真正差别。

Italy

意大利

At first sight, the coming of a united Italian nation represented a major shift in the European balances. Instead of being a cluster of rivaling small states, partly under foreign sovereignty and always under the threat of foreign intervention, there was now a solid block of thirty million people growing so swiftly that it was coming close to France’s total population by 1914. Its army and its navy in this period were not especially large, but as Tables 19 and 20 show, they were still very respectable.

乍一看,一个统一的意大利的出现使欧洲的均势发生了重大变化。它已不再是部分主权操在外国人手里、经常受外来干涉威胁的相互敌对的一群小城邦,而是一个有3000万人口的稳固的整体,其人口增加很快,到1914年时已接近法国的人口。这个时期它的陆海军规模不是特别大,但正如表19和表20表明的那样,他们还是不容忽视的。

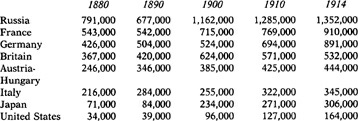

Table 19. Military and Naval Personnel of the Powers, 1880–1914 26

表19 1880~1914年各大国的陆海军人数

(单位:万人)

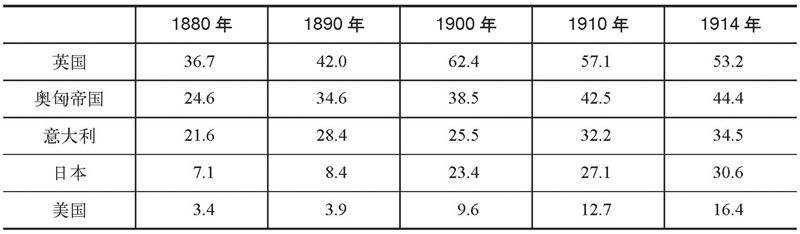

Table 20. Warship Tonnage of the Powers, 1880–191427

表20 1880~1914年各大国的战舰吨位

(单位:万吨)

In diplomatic terms, as was noted above,28 the rise of Italy certainly impinged upon its two Great Power neighbors, France and Austria-Hungary; and while its entry into the Triple Alliance in 1882 ostensibly “resolved” the Italo-Austrian rivalry, it confirmed that an isolated France faced foes on two fronts. Within just over a decade from its unification, therefore, Italy seemed a full member of the European Great Power system, and Rome ranked alongside the other major capitals (London, Paris, Berlin, St. Petersburg, Vienna, Constantinople) as a place to which full embassies were accredited.

如上所示,从外交上看,意大利的兴起必然冲击着它的两大邻国——法国和奥匈帝国。它在1882年加入三国同盟,这表面上“解决了”意奥两国的对抗,也进一步确立了孤立的法国两面受敌的局势。所以,就在它统一后10年的时间里,意大利似乎已完全成为欧洲大国体系中的一员,罗马也同其他首都(伦敦、巴黎、柏林、圣彼得堡、维也纳、君士坦丁堡)一样,成为外国派遣全权大使驻节的地方。

But the appearance of Italy’s Great Power status covered some stupendous weaknesses, above all the country’s economic retardation, particularly in the rural south. Its illiteracy rate—37. 6 percent overall and again far greater in the south— was much higher than in any other western or northern European state, a reflection of the backwardness of much of Italian agriculture—smallholdings, poor soil, little investment, sharecropping, inadequate transport. Italy’s total output and per capita national wealth were comparable to those of the peasant societies of Spain and eastern Europe rather than those of the Netherlands or Westphalia. Italy had no coal; yet, despite its turn to hydroelectricity, about 88 percent of Italy’s energy continued to come from British coal, a drain upon its balance of payments and an appalling strategical weakness. In these circumstances, Italy’s rise in population without significant industrial expansion was a mixed blessing, since it slowed its industrial growth in per capita terms relative to the other western Powers,29 and the comparison would have been even more unfavorable had not hundreds of thousands of Italians (usually the more mobile and able) emigrated across the Atlantic each year. All this made it, in Kemp’s phrase, “the disadvantaged latecomer. ”30

但是,意大利以大国地位出现却掩盖了它的一些致命弱点。首先是整个国家经济的停滞,特别是南部乡村地区。它的文盲率在全国为37.6%,而其南部更为严重,远远高于西欧和北欧的任何国家。这反映了意大利大部分农业地区的落后性——小农经济、贫瘠的土壤、少量的投资、实物地租、不能满足需要的运输条件。意大利的生产和人均国民财富只能与西班牙和东欧的农业社会相比,而不能与荷兰或威斯特伐利亚相比。其次,意大利无煤,而且,尽管已转向水力发电,但它88%的能源仍来自英国的煤,这就成了维持收支平衡的沉重负担,相应地也就成了可怕的战略弱点。在工业没有获得重大进展的前提下,意大利的人口增加就成了一个祸福参半的事情。因为它与其他西方大国相比,减缓了人均工业增长率;假如每年没有成千上万的意大利人(往往是很有活力和才干的人)横渡大西洋向彼岸移民,这种对比对意大利就更为不利,用肯普的话来说,所有这些,使意大利成为“不利的后来者”。

This is not to say that there was no modernization. Indeed, it is precisely about this period that many historians have referred to “the industrial revolution of the Giolittian era” and to “a decisive change in the economic life of our country. ”31 At least in the north, there was a considerable shift to heavy industry—iron and steel, shipbuilding, automobile manufacturing, as well as textiles. In Gerschrenkon’s view, the years 1896–1908 witnessed Italy’s “big push” toward industrialization; indeed, Italian industrial growth rose faster than anywhere else in Europe, the population shift from the countryside to the towns intensified, the banking system readjusted itself in order to provide industrial credit, and real national income moved sharply upward. 32 Piedmontese agriculture showed similar steps forward.

但这并不是说,意大利就没有现代化了。的确,正是在这一时期,许多历史学家提到了“乔利蒂[3]时代的工业革命”和“我国的经济生活中发生了决定性的变化”。至少在北方,已发生了向重工业方面的重大转移。在格申克龙看来,1896~1908年,意大利经历了朝工业化方向的“大奋进”。的确,这时意大利的工业发展速度比欧洲其他任何地方都快,人口从农村向城镇的转移加快了,银行体系为提供工业信用贷款重新进行了自我调整,国际的实际收入在迅速上升,皮埃蒙特地区的农业也表现出相似的前进步伐。

However, once the Italian statistics are placed in comparative prospective, the gloss begins to fade. It did create an iron and steel industry, but in 1913 its output was one-eighth that of Britain, one-seventeenth that of Germany, and only two-fifths that of Belgium. 33 It did achieve swift rates of industrial growth, but that was from such a very low beginning level that the real results were not impressive. At the outset of the First World War, it had not achieved even one-quarter of the industrial strength which Great Britain possessed in 1900, and its share of world manufacturing production actually dropped, from a mere 2. 5 percent in 1900 to 2. 4 percent in 1913. Although Italy marginally entered the listings of Great Powers, it is worth noting that—Japan excluded—every other of these powers had two or three times its industrial muscle; some (Germany and Britain) had sixfold the amount, and one (the United States) over thirteen times.

然而,一旦把有关意大利的统计数字进行比较性的剖析,其光泽就显得暗淡了。它确实创建了钢铁工业,但它在1913年的产量只是英国的1/8,德国的l/7,比利时的2/5。其工业增长率确实很快,但起点很低,以致其成果并不怎么显著。在第一次世界大战爆发时,它的工业能力尚未达到英国1900年的1/4。它在世界制造业生产中所占的份额实际上下降了,从1900年仅有的2.5%,下降到1913年的2.4%。尽管意大利勉强够格进入大国行列,但需要指出的是,除日本外,其他每个大国的工业潜力都是其两倍、三倍,有的国家(德国、英国)是它的6倍,还有一个国家(美国)是它的13倍以上。

This might have been compensated for somewhat by a relatively greater degree of national cohesion and resolve on the part of the Italian population, but such elements were absent. The loyalties which existed in the Italian body politic were familial and local, perhaps regional, but not national. The chronic gap between north and south, which the industrialization of the former only exacerbated, and the lack of any great contact with the world outside the village community in so many parts of the peninsula were not helped by the hostility between the Italian government and the Catholic Church, which forbade its members to serve the state. The ideals of risorgimento, hailed by native and admiring foreign liberals, did not penetrate very far down Italian society. Recruitment for the armed services was difficult, and the actual location of army units according to strategical principles, rather than regional political calculations, was impossible. Civil-military relationships at the top were characterized by a mutual miscomprehension and distrust. The general antimilitarism of Italian society, the poor quality of the officer corps, and the lack of adequate funding for modern weaponry raised doubts about Italian military effectiveness long before the disastrous 1917 battle of Caporetto or the 1940 Egyptian campaign. 34 Its unification wars had relied upon the intervention of France, and then the threat to Austria-Hungary from Prussia. The 1896 catastrophe at Adowa (in Abyssinia) gave Italy the awful reputation of having the only European army defeated by an African society without means of effective response. The Italian government decision to make war in Libya in 1911–1912, which took the Italian general staff itself by surprise, was a financial disaster of the first order. The navy, looking very large in 1890, steadily declined in relative size and was always of questionable efficiency. Successive Mediterranean commander in chiefs of the Royal Navy always hoped that the Italian fleet would be neutral, not allied, if it ever came to a war with France in this period. 35

假如意大利有较强的民族内聚力和其民族所表现出来的决心,这些弱点也许能多少得到弥补,但这些因素都不存在。意大利国家中存在的忠诚是家族性的、地方性的,也许是地区性的,但绝不是全国性的。这样,早就开始发展的北方工业化只能加剧北方同南方的差距;这个半岛许多地方的村社团体缺乏与外界的重要联系。由于意大利政府同天主教会的对立没有改善,天主教会禁止其教徒为这个国家服务。受本国人欢迎和外国自由主义者羡慕的复兴思想并没有渗透到意大利社会中去。军队征兵很困难,而且按战略需要而不按地区政治的考虑分驻军队是不可能的。高层文官和军队的关系的特点是相互不理解和不信任。普遍的反军国主义情绪、军官素质的低劣以及缺乏制造现代武器所需要的资金等,增强了人们对其军事力量的怀疑。这种怀疑早在灾难性的1917年卡波雷托战役或1940年的埃及战役中就产生了。它的统一战争靠的是法国的干涉和后来普鲁士对奥匈帝国的威胁。1896年在阿杜瓦(在阿比西尼亚)的大惨败使意大利信誉扫地,意大利军队是唯一被一个没有有效反击手段的非洲国家打败了的欧洲军队。意大利政府做出的使其总参谋部感到意外的1911~1912年在利比亚进行战争的决定,是最严重的财政上的灾难。意大利的海军在1890年时看起来很强大,但其相对的规模却越来越小,并且战斗力通常令人怀疑。地中海地区的英国皇家海军的几任总司令总是希望意大利舰队保持中立而不是结盟,如果英国和法国在这个时期交战的话。

The consequences of all this upon Italy’s strategical and diplomatic position were depressing. Not only was the Italian general staff acutely aware of its numerical and technical inferiority compared with the French (especially) and the Austro- Hungarians, but it also knew that Italy’s inadequate railway network and the deeprooted regionalism made impossible large-scale, flexible troop deployments in the Prussian manner. And not only was the Italian navy aware of its deficiencies, but Italy’s vulnerable and lengthy coastline made its alliance politics extremely ambivalent, and thus made strategic planning more chaotic than ever. The alliance treaty that Italy signed in 1882 with Berlin was comforting at first, particularly when Bismarck seemed to paralyze the French; but even then the Italian government kept pressing for closer ties with Britain, which alone could neutralize the French fleet. When, in the years after 1900, Britain and France moved closer together and Britain and Germany moved from cooperation to antagonism, the Italians felt that they had little alternative but to tack toward the new Anglo-French combination. The residual dislike of Austria-Hungary strengthened this move, just as the respect for Germany and the importance of German industrial finance in Italy checked it from being an open break. Thus by 1914, Italy occupied a position like that of 1871. It was “the least of the Great Powers,”36 frustratingly unpredictable and unscrupulous in the eyes of its neighbors, and possessing commercial and expansionist ambitions in the Alps, the Balkans, North Africa, and farther afield which conflicted with the interests of both friends and rivals. Economic and social circumstances continued to weaken its power to influence events, and yet it remained a player in the game. In sum, the judgment of most other governments seems to have been that it was better to have Italy as a partner than as a foe; but the margin of benefit was not great. 37

所有这些对意大利战略和外交地位产生的影响是令人沮丧的。意大利总参谋部非常清楚,无论在数量上还是在技术上,无论是与法国相比还是与奥匈帝国相比,意大利都处于劣势,而且它还知道,铁路运输的不足和根深蒂固的地方主义,使得意大利不能像普鲁士那样对军队进行大规模的灵活调动。不仅意大利海军明白它的低效率,而且意大利易受攻击,加上漫长的海岸线,都使其结盟政治处于很矛盾的境地。因此使战略计划的制订比以往任何时期都混乱。意大利同柏林在1882年签订的盟约起初是令人鼓舞的,特别是当俾斯麦看来要使法国陷于瘫痪时;甚至在此时,意大利政府也努力同英国保持着十分密切的关系,因为仅仅英国一个国家就能抵消法国舰队的力量。1900年以后的几年中,当英、法关系趋于密切,而英国和德国由合作走向对立时,意大利人感到,除了见风使舵、转向新的英法联盟外,几乎别无选择。讨厌奥匈帝国的残余情绪,加速了这种行动,正如尊重德意志的心理及德意志在意大利的工业金融中的重要性妨碍了意大利与其公开决裂一样。因此,到1914年时,意大利又处于像1871年那样的境地。它是“大国中最小的一个”,在其邻国心目中,它令人失望地使人捉摸不透,并且寡廉鲜耻;它对阿尔卑斯地区、巴尔干地区、北非和更远的地区怀有商业上的和扩张主义的野心,这样就与敌友的利益都发生了冲突。经济和社会状况继续削弱着它影响事态发展的能力。它仍然是钩心斗角的角逐中的一方。简言之,在其他大多数国家的政府看来,与意大利为敌,不如与其结成伙伴;但二者之间的利害差距并不大。

Japan

日本

Italy was a marginal member of the Great Power system in 1890, but Japan wasn’t even in the club. For centuries it had been ruled by a decentralized feudal oligarchy consisting of territorial lords (daimyo) and an aristocratic caste of warriors (samurai). Hampered by the absence of natural resources and by a mountainous terrain that left only 20 percent of its land suitable for cultivation, Japan lacked all of the customary prerequisites for economic development. Isolated from the rest of the world by a complex language with no close relatives and an intense consciousness of cultural uniqueness, the Japanese people remained inward-looking and resistant to foreign influences well into the second half of the nineteenth century. For all these reasons, Japan seemed destined to remain politically immature, economically backward, and militarily impotent in World Power terms. 38 Yet within two generations it had become a major player in the international politics of the Far East.

1890年时意大利是大国体系中一位刚够格的成员,而日本甚至还未进入这个俱乐部。几个世纪以来,日本一直被由各霸一方的大领主和武士贵族集团组成的分散的封建寡头集团所统治。由于缺乏自然资源并受多山地区的限制,日本只有20%的土地宜于耕种,它缺乏经济发展通常应具备的所有先决条件。日本人民因具有一种没有相近语种的复杂的语言和强烈的独特文化的意识,而孤立于世界其他地区之外,所以直到19世纪下半期的相当长一段时期,他们仍保持内向的特性,对外部影响持抵制态度。由于所有这些原因,日本似乎注定在政治上不成熟,在经济上落后,用大国标准来衡量,它在军事上也软弱。但在两代人的时间里,它已成为远东国际政治中的一个主要角色。

The cause of this transformation, effected by the Meiji Restoration from 1868 onward, was the determination of influential members of the Japanese elite to avoid being dominated and colonized by the West, as seemed to be happening elsewhere in Asia, even if the reform measures to be taken involved the scrapping of the feudal order and the bitter opposition of the samurai clans. 39 Japan had to be modernized not because individual entrepreneurs wished it, but because the “state” needed it. After the early opposition had been crushed, modernization proceeded with a dirigisme and commitment which makes the efforts of Colbert or Frederick the Great pale by comparison. A new constitution, based upon the Prusso-German model, was established. The legal system was reformed. The educational system was vastly expanded, so that the country achieved an exceptionally high literacy rate. The calendar was changed. Dress was changed. A modern banking system was evolved. Experts were brought in from Britain’s Royal Navy to advise upon the creation of an up-to-date Japanese fleet, and from the Prussian general staff to assist in the modernization of the army. Japanese officers were sent to western military and naval academies; modern weapons were purchased from abroad, although a native armaments industry was also established. The state encouraged the creation of a railway network, telegraphs, and shipping lines; it worked in conjunction with emerging Japanese entrepreneurs to develop heavy industry, iron, steel, and shipbuilding, as well as to modernize textile production. Government subsidies were employed to benefit exporters, to encourage shipping, to get a new industry set up. Japanese exports, especially of silk and textiles, soared. Behind all this lay the impressive political commitment to realize the national slogan fukoku kyohei (“rich country, with strong army”). For the Japanese, economic power and military/naval power went hand in hand.

从1868年起,日本实行明治维新。这次改革的原因是,日本的上层统治者决心避免日本像在亚洲其他地方正在发生的那样被西方控制和殖民化,即使要采取的改革措施会引起封建秩序的衰落并遭到武士集团的激烈反对,日本也不得不实行现代化。这并不是因为个别的企业家希望这样,而是因为“国家”的需要。早期的反对势力被粉碎后,现代化以一种使柯尔贝尔或腓特烈大帝的努力相形见绌的统治经济和信念在进行着。日本制定了一部以普鲁士德国的宪法为蓝本的宪法,对法制进行了改革。教育制度也有很大发展,使这个国家的人民达到了罕见的高识字率。历法和穿着也都改变了。一种现代银行体制逐渐形成。从英国皇家海军请来的专家为日本建立一支现代海军出谋划策,从普鲁士总参谋部请来的专家帮助它实现陆军的现代化。日本军官被派往西方国家的陆军和海军学院学习,尽管本国已建立起军火工业,但仍从国外购买现代化武器。政府鼓励建立铁路网、电报和航运线;它还与日本新出现的企业家们一起发展重工业和钢铁、造船业,并使纺织业生产现代化。政府的补贴使出口商受益,补贴还用于鼓励航运和建立一个新的工业。日本的出口产品,特别是丝绸和纺织品猛增。在所有这一切的背后,有着引人注目的政治义务,即实现国家“富国强兵”的号召。对于日本人来说,经济实力和陆海军实力是同步发展的。

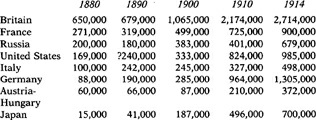

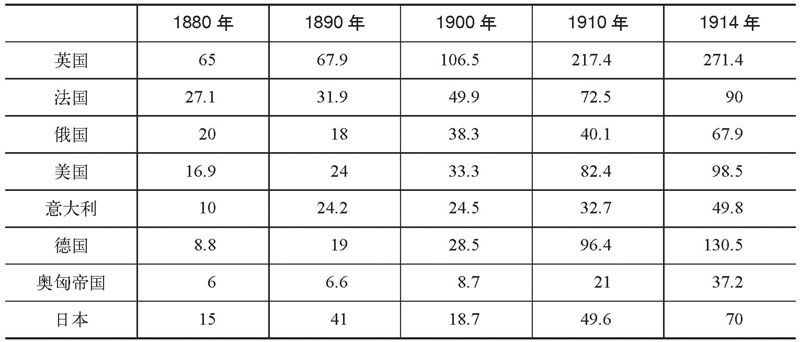

But all this took time, and the handicaps remained severe. 40 Although the urban population more than doubled between 1890 and 1913, numbers engaged on the land remained about the same. Even on the eve of the First World War, over threefifths of the Japanese population was engaged in agriculture, forestry, and fishing; and despite all the many improvements in farming techniques, the mountainous countryside and the small size of most holdings prevented an “agricultural revolution” on, say, the British model. With such a “bottom-heavy” agricultural base, all comparisons of Japan’s industrial potential or of per capita levels of industrialization were bound to show it at or close to the lower end of the Great Power lists (see Tables 14 and 17 above). While its pre-1914 industrial spurt can clearly be detected in the large rise of its energy consumption from modern fuels and in the increase in its share of world manufacturing production, it was still deficient in many other areas. Its iron and steel output was small, and it relied heavily upon imports. In the same way, although its shipbuilding industry was greatly expanded, it still ordered some warships elsewhere. It also was very short of capital, needing to borrow increasing amounts from abroad but never having enough to invest in industry, in infrastructure, and in the armed services. Economically, it had performed miracles to become the only nonwestern state to go through an industrial révolution in the age of high imperialism; yet it still remained, compared to Britain, the United States, and Germany, an industrial and financial lightweight.

但所有这些发展是需要时间的,不利条件仍然很严重。尽管1890年至1913年城市人口增加了一倍多,但种地的人数几乎仍与原来一样多。甚至到了第一次世界大战前夕,仍有3/5以上的日本人在从事农业、林业和渔业;而且尽管农耕技术有了许多改进,但多山的农村和大多数是小块土地的经营,阻碍了说像英国那样的“农业革命”的发生。由于这种“极落后的”农业基础,日本的工业潜力或人均工业化水平与其他国家一经比较,都必然使它处于或接近于末流大国的地位(见前面的表14和表17)。虽然1914年以前其工业的突然兴起可以从其现代燃料能源消耗的大幅度增长和在世界制造业产量中所占份额的增加中清楚地看到,但它在其他方面仍很欠缺。它的钢铁产量很低,严重依赖进口。同样,虽然它的造船业有了很大发展,但它仍从其他国家定购军舰。它还很缺乏资本,需要越来越多地举借外债,但从来不足以向工业、基础工业和军事部门投资。在经济上,它完成了一个奇迹,在帝国主义鼎盛时期成为经历工业革命的唯一的非西方国家;但与英国、美国和德国相比,它在工业和金融方面仍是一个无足轻重的国家。

Two further factors, however, aided Japan’s rise to Great Power status and help to explain why it surpassed, for example, Italy. The first was its geographical isolation. The nearby continental shore was held by nothing more threatening than the decaying Chinese Empire. And while China, Manchuria, and (even more alarming) Korea might fall into the hands of another Great Power, geography had placed Japan far closer to those lands than any one of the other imperialist states—as Russia was to find to its discomfort when it tried to supply an army along six thousand miles of railway in 1904–1905, and as the British and American navies were to discover several decades later as they wrestled with the logistical problems involved in the relief of the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Malaya. Assuming a steady Japanese growth in East Asia, it would only be by the most extreme endeavors that any other major state could prevent Japan from becoming the predominant power there in the course of time.

还有两个因素帮助了日本上升到大国地位,并有助于说明它为什么会超过意大利。第一个因素是地理上的隔绝状态。其附近的大陆海岸由当时腐朽的中华帝国所有,不足为患。当中国东北和(甚至更使它恐慌的)朝鲜可能落入另一个大国手中时,地理环境使日本比其他任何一个帝国主义国家都更为接近这些地区。俄国在1904~1905年试图沿着6000英里的铁路运送军队时就感到了不便,几十年之后英美海军救援菲律宾、中国香港和马来亚时,就发现需要尽力克服后勤的困难。假如日本的势力在东亚稳步发展的话,其他任何一个大国只有尽最大努力才能防止日本在那个时代在那个地区变成一个占统治地位的国家。

The second factor was moral. It seems indisputable that the strong Japanese sense of cultural uniqueness, the traditions of emperor worship and veneration of the state, the samurai ethos of military honor and valor, the emphasis upon discipline and fortitude, produced a political culture at once fiercely patriotic and unlikely to be deterred by sacrifices and reinforced the Japanese impulses to expand into “Greater East Asia,” for strategical security as well as markets and raw materials. This was reflected in the successful military and naval campaigning against China in 1894, when those two countries quarreled over their claims in Korea. 41 On land and sea, the better-equipped Japanese forces seemed driven by a will to succeed. At the end of that war, the threats of the “triple intervention” by Russia, France, and Germany compelled an embittered Japanese government to withdraw its claims to Port Arthur and the Liaotung Peninsula, but that merely increased Tokyo’s determination to try again later. Few, if any, in the government dissented from Baron Hayashi’s grim conclusion:

第二个因素是士气。毋庸置疑的是,日本人对文化的独特性的强烈意识,对天皇崇拜和国家崇拜的传统,军人的光荣感和勇猛的武士道精神,对纪律和刚毅的强调,产生了一种强烈的爱国主义和不畏牺牲的政治文化,加强了日本为战略上的安全和获取市场及原材料而扩张为“大东亚”圈这一目标的动力。这反映在1894年同中国进行的成功的陆战和海战中,那次战争是由于两国在朝鲜的权利的争执引起的。在陆上和海上,装备较好的日本军队似乎是被获胜愿望所驱使。在战争结束时,俄国、法国和德国“三方干涉”的威胁,迫使愤怒的日本政府撤回了它对中国大连和辽东半岛的要求,但这只不过增强了东京日后再干的决心。在政府中,不同意林权助男爵得出的严厉结论的人即使有,为数也不多:

If new warships are considered necessary we must, at any cost, build them: if the organization of our army is inadequate we must start rectifying it from now; if need be, our entire military system must be changed. …

如果我们认为必须有新的战舰,就要不惜任何代价去建造;如果我们军队的组织不合适,我们必须从现在起就开始整顿;如果需要,我们的整个军事体制就必须进行变革……

At present Japan must keep calm and sit tight, so as to lull suspicions nurtured against her; during this time the foundations of national power must be consolidated; and we must watch and wait for the opportunity in the Orient that will surely come one day. When this day arrives, Japan will decide her own fate …,42

现在日本必须保持冷静和坚持自己的主张,以便使对它的猜疑自然平息;在此期间,必须巩固国家力量的基础;我们必须在东方静观和等待机会,这个机会总有一天会到来。当这一天到来时,日本将决定它自己的命运……

Its time for revenge came ten years later, when its Korean and Manchurian ambitions clashed with those of czarist Russia. 43 While naval experts were impressed by Admiral Togo’s fleet when it destroyed the Russian ships at the decisive battle of Tsushima, it was the general bearing of Japanese society which struck other observers. The surprise strike at Port Arthur (a habit begun in the 1894 China conflict, and revived in 1941) was applauded in the West, as was the enthusiasm of Japanese nationalist opinion for an outright victory, whatever the cost. More remarkable still seemed the performance of Japan’s officers and men in the land battles around Port Arthur and Mukden, where tens of thousands of soldiers were lost as they charged across minefields, over barbed wire, and through a hail of machine-gun fire before conquering the Russian trenches. The samurai spirit, it seemed, could secure battlefield victories with the bayonet even in the age of mass industrialized warfare. If, as all the contemporary military experts concluded, morale and discipline were still vital prerequisites of national power, Japan was rich in those resources.

10年之后,当它对朝鲜和中国东北的野心与沙皇俄国的野心发生冲突时,报复的时机到来了。如果说海军大将东乡平八郎的舰队在对马海峡的决战中摧毁俄国舰队使海军战史专家们对日本舰队留下了深刻的印象,那么日本社会总的态度则使其他观察家们感到震惊。日本对大连进行了出其不意的打击(这种做法始于1894年同中国的战争,后在1941年再度使用),日本民族主义者为获得彻底胜利而不惜付出一切代价的热情在西方受到了欢迎。更引人注目的似乎还是日本军队在大连和沈阳周围的陆战中的表现,在这次战斗中,有数万名士兵冲过布雷区,越过铁丝网,冒着俄国人重机枪的扫射,在攻占俄军战壕之前丧生。即使在大规模工业化的年代,武士道精神加上刺刀似乎也能保证战场上的胜利。就如所有同时代的军事专家们断言的,如果士气和纪律仍然是国家实力极为重要的先决条件的话,日本在这些资源方面是非常富有的。

Even then, however, Japan was not a full-fledged Great Power. Japan had been fortunate to have fought an even more backward China and a czarist Russia which was militarily top-heavy and disadvantaged by the immense distance between St. Petersburg and the Far East. Furthermore, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 had allowed it to fight on its home ground without interference from third powers. Its navy had relied upon British-built battleships, its army upon Krupp guns. Most important of all, it had found the immense costs of the war impossible to finance from its own resources and yet had been able to rely upon loans floated in the United States and Britain. 44 As it turned out, Japan was close to bankruptcy by the end of 1905, when the peace negotiations with Russia got under way. That may not have been obvious to the Tokyo public, which reacted furiously to the relatively light terms with which Russia escaped in the final settlement. Nevertheless, with victory confirmed, Japan’s armed forces glorified and admired, its economy able to recover, and its status as a Great Power (albeit a regional one) admitted by all, Japan had come of age. No one could do anything significant in the Far East without considering its response; but whether it could expand further without provoking reaction from the more established Great Powers was not at all clear.

但是即使那时,日本也不是一个羽毛丰满的大国。日本很幸运地战胜了更为落后的中国和军界上层臃肿、因圣彼得堡和远东之间相距遥远而处境不利的俄国。此外,1902年缔结的英日同盟也使它得以在不受第三国干涉的情况下,在自己熟悉的区域里作战。其海军依靠的是英国制造的战舰,其陆军依靠的是克虏伯制造的枪炮。最重要的是,它发现自己的资源不可能在财政上负担战争的巨额费用,只能够依赖在英美筹措的贷款。结果是,1905年底在与俄国进行和平谈判时,日本财政已处于崩溃的边缘。东京的公众对此可能感觉不太明显,他们对使俄国在最后达成的协议中得以摆脱困境的较为宽容的条件感到愤怒。但结果是,由于胜利已经肯定,日本军队感到自豪并受到了赞扬,其经济得以恢复,而且其大国地位(尽管是地区性的)得到了所有大国的承认,日本成熟了。在远东,如不考虑它的反应就做不成任何重要事情;但它是否能够进一步扩张而不引起资格更老的大国的反应,彼时还一点儿也不清楚。

Germany

德国

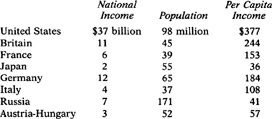

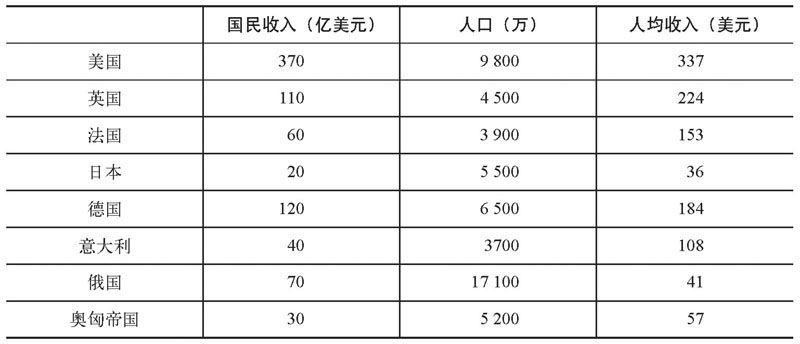

Two factors ensured that the rise of imperial Germany would have a more immediate and substantial impact upon the Great Power balances than either of its fellow “newcomer” states. The first was that, far from emerging in geopolitical isolation, like Japan, Germany had arisen right in the center of the old European states system; its very creation had directly impinged upon the interests of Austria- Hungary and France, and its existence had altered the relative position of all of the existing Great Powers of Europe. The second factor was the sheer speed and extent of Germany’s further growth, in industrial, commercial, and military/naval terms. By the eve of the First World War its national power was not only three or four times Italy’s and Japan’s, it was well ahead of either France or Russia and had probably overtaken Britain as well. In June 1914 the octogenarian Lord Welby recalled that “the Germany they remembered in the fifties was a cluster of insignificant states under insignificant princelings”;45 now, in one man’s lifetime, it was the most powerful state in Europe, and still growing. This alone was to make “the German question” the epicenter of so much of world politics for more than half a century after 1890.

有两个因素确保了德意志帝国的崛起将比其“新来的”伙伴对大国之间的均势产生更直接和更大的影响。第一个因素是,德国远不像日本那样是一个从孤立状态中出现的国家,而是在旧的欧洲国家体系的中心崛起的,它的建立直接冲击着奥匈帝国和法国的利益,而它的存在改变了当时欧洲各大国之间的相对地位。第二个因素是德国在工业、商业和陆海军方面进一步发展的绝对速度和程度。到第一次世界大战前夕,它的国力不仅是意大利和日本的3倍或4倍,而且还超过了法国或俄国,很可能还赶上了英国。1914年6月,80多岁的韦尔比勋爵回忆说:“他们记得在19世纪50年代时,德意志是一群由无足轻重的王室成员统治下的无足轻重的邦”;现在,在一个人的有生之年中,它是欧洲最强大的国家,而且仍在发展。单是这一点就使得“德国问题”成为1890年以后半个多世纪里这么多世界政治事务的中心。

Only a few details of Germany’s explosive economic growth can be offered here. 46 Its population had soared from 49 million in 1890 to 66 million in 1913, second only in Europe to Russia’s—but since Germans enjoyed far higher levels of education, social provision, and per capita income than Russians, the nation was strong both in the quantity and the quality of its population. Whereas, according to an Italian source, 330 out of 1,000 recruits entering its army were illiterate, the corresponding ratios were 220/1,000 in Austria-Hungary, 68/1,000 in France, and an astonishing 1/1,000 in Germany. 47 The beneficiaries were not only the Prussian army, but also the factories requiring skilled workers, the enterprises needing welltrained engineers, the laboratories seeking chemists, the firms looking for managers and salesmen—all of which the German school system, polytechnical institutes, and universities produced in abundance. By applying the fruits of this knowledge to agriculture, German farmers used chemical fertilizers and large-scale modernization to increase their crop yields, which were much higher per hectare than in any of the other Great Powers. 48 To appease the Junkers and the peasants’ leagues, German farming was given considerable tariff protection in the face of more cheaply produced American and Russian foodstuffs; yet because of its relative efficiency, the large agricultural sector did not drag down per capita national income and output to anything like the degree it did in all the other continental Great Powers.

这里只能提供一点点有关德国经济飞速发展的细节。它的人口从1890年的4900万猛增到1913年的6600万,在欧洲仅次于俄国,但由于德国比俄国的教育水平、社会供应和人均收入都高得多,所以这个国家的人口在数量上和质量上都是强大的。据一份意大利的资料反映,意大利军队招募的每千名新兵中,有330名是文盲;而奥匈帝国是每千人中有220名,法国是每千人中有68名,令人吃惊的是,德国每千人中只有一个文盲。获益的不仅是普鲁士军队,而且还有需要熟练工人的工厂,需要受过良好训练的工程师的企业,寻求化学家的实验室,期望得到管理人员和推销员的公司——德国的学校体制、多种科技的学院和大学,能够大量培养上述的人才。通过把这些知识的成果运用到农业上去,德国的农民使用化肥和大规模实行现代化来提高粮食产量,它每公顷的产量比其他任何一个大国都高得多。为了安抚容克豪族和农民组成的团体,德国的农业实行了许多关税保护措施以对付粮食生产成本更低的美国和俄国;而由于它的高效率,巨大的农业部门并没有使人均国民收入和产量降低到像欧洲大陆其他国家因农业而降低的水平。

But it was in its industrial expansion that Germany really distinguished itself in these years. Its coal production grew from 89 million tons in 1890 to 277 million tons in 1914, just behind Britain’s 292 million and far ahead of Austria-Hungary’s 47 million, France’s 40 million, and Russia’s 36 million. In steel, the increases had been even more spectacular, and the 1914 German output of 17. 6 million tons was larger than that of Britain, France, and Russia combined. More impressive still was the German performance in the newer, twentieth-century industries of electrics, optics, and chemicals. Giant firms like Siemens and AEG, employing 142,000 people between them, dominated the European electrical industry. German chemical firms, led by Bayer and Hoechst, produced 90 percent of the world’s industrial dyes. This success story was naturally reflected in Germany’s foreign-trade figures, with exports tripling between 1890 and 1913, bringing the country close to Britain as the leading world exporter; not surprisingly, its merchant marine also expanded, to be the second-largest in the world by the eve of the war. By then, its share of world manufacturing production (14. 8 percent) was higher than Britain’s (13. 6 percent) and two and a half times that of France (6. 1 percent). It had become the economic powerhouse of Europe, and even its much-publicized lack of capital did not seem to be slowing it down. Little wonder that nationalists like Friedrich Naumann exulted at these manifestations of growth and their implications for Germany’s place in the world. “The German race brings it,” he wrote. “It brings army, navy, money and power. … Modern, gigantic instruments of power are possible only when an active people feels the spring-time juices in its organs. ”49

但就是在它的工业发展中,德国才真正地在这些年里显示出特色。它的煤产量从1890年的8900万吨上升到1914年的2.77亿吨,只落后于英国的2.92亿吨,远远领先于奥匈帝国的4700万吨、法国的4000万吨和俄国的3600万吨。德国钢产量的增长更加惊人,1914年,德国1760万吨的产量高于英、法、俄三国的产量总和。更引人注目的还是德国在电力、光学和化学等20世纪新兴工业中所取得的进展。像西门子和AEG公司这样的大公司,雇用着14.2万名工人,它们控制着欧洲的电力工业。德国以拜尔和霍奇斯特为首的化学公司生产了世界工业染料的90%。这段成功的历史自然反映在德国的外贸数字中,从1890年到1913年,德国的出口增加了两倍,使它接近世界头号出口国英国。以下事实并不使人感到惊讶:它的商船大大增加了,在第一次世界大战前夕成为世界第二大商船拥有国。那时,它在世界制造业中所占的份额(14.8%)高于英国(13.6%),约是法国的2.5倍(6.1%)。它已成为欧洲的经济动力源泉,甚至它广为宣传的资本短缺似乎也没有降低它的发展速度。民族主义者弗雷德里希·瑙曼为这些发展以及这些发展对德国的世界地位所具有的含义感到欢欣鼓舞,几乎没有什么人对这种情景感到不解。瑙曼写道:“德意志种族带来了发展,发展又带来了陆军、海军、钱和权力……只有当一个活跃的民族在它的喉管里感觉到春天的甘汁时,现代的、庞大的权力工具才可能产生。”

That publicists such as Naumann and, even more, such rabidly expansionist pressure groups as the Pan-German League and the German Navy League should have welcomed and urged the rise of German influence in Europe and overseas is hardly surprising. In this age of the “new imperialism,” similar calls could be heard in every other Great Power; as Gilbert Murray wickedly observed in 1900, each country seemed to be asserting, “We are the pick and flower of nations … above all things qualified for governing others. ”50 It was perhaps more significant that the German ruling elite after 1895 also seemed convinced of the need for large-scale territorial expansion when the time was ripe, with Admiral Tirpitz arguing that Germany’s industrialization and overseas conquests were “as irresistible as a natural law”; with the Chancellor Bülow declaring, “The question is not whether we want to colonize or not, but that we must colonize, whether we want it or not”; and with Kaiser Wilhelm himself airily announcing that Germany “had great tasks to accomplish outside the narrow boundaries of old Europe” although he also envisaged it exercising a sort of “Napoleonic supremacy,” in a peaceful sense, over the continent. 51 All this was quite a change of tone from Bismarck’s repeated insistence that Germany was a “saturated” power, keen to preserve the status quo in Europe and unenthused (despite the colonial bids of 1884–1885) about territories overseas. Even here it may be unwise to exaggerate the particularly aggressive nature of this German “ideological consensus”52 for expansion; statesmen in France and Russia, Britain and Japan, the United States and Italy were also announcing their country’s manifest destiny, although perhaps in a less deterministic and frenetic tone.

像瑙曼这样的宣传家们,甚至还有像泛德意志联盟和德意志海上联盟这样狂热的扩张主义集团,竟欢迎和敦促德国增强在欧洲和海外的影响,这不怎么令人吃惊。在这一“新帝国主义时期”,在其他任何一个大国里,都能听到相类似的呼吁。就如吉尔伯特·默里在1900年所作的令人厌恶的评论,每一个国家似乎都会宣称,“我们是所有民族中的精华……最有资格统治其他民族”。也许更重要的是,1895年以后,德国的统治者上层似乎也相信需要在时机成熟时大规模地扩张领土。海军上将蒂尔皮茨坚持认为,德国的工业化和海外征服“像自然法则一样不可抗拒”;首相比洛宣称,“问题不是我们是否要殖民,而是我们必须殖民,不管我们是否想殖民”;威廉皇帝自己也轻率地宣布,德国“要在旧欧洲狭窄的边界之外完成重要任务”,虽然他也想到过德国在和平的意义上在欧洲大陆行使“拿破仑式的霸权”。所有这些,与俾斯麦一再坚持的德国是一个“饱和的”、渴望维持欧洲现状而对海外领土没有热情的(尽管1884~1885年有过殖民企图)国家的腔调相比,是一种彻底的转变。在这里夸大德国“意识形态上一致”要求扩张的特殊的侵略性是不明智的;法国和俄国、英国和日本、美国和意大利的政治家们也宣布了它们国家的天定命运,尽管他们也许是以一种不那么带决定论的、狂热的语调宣布的。

What was significant about German expansionism was that the country either already possessed the instruments of power to alter the status quo or had the material resources to create such instruments. The most impressive demonstration of this capacity was the rapid buildup of the German navy after 1898, which under Tirpitz was transformed from being the sixth-largest fleet in the world to being second only to the Royal Navy. By the eve of war, the High Seas Fleet consisted of thirteen dreadnought-type battleships, sixteen older ones, and five battlecruisers, a force so big that it had compelled the British Admiralty gradually to withdraw almost all its capital-ship squadrons from overseas stations into the North Sea; while there were to be indications (better internal construction, shells, optical equipment, gunnery control, night training, etc. ) that the German vessels were pound for pound superior. 53 Although Tirpitz could never secure the enormous funds to achieve his real goal of creating a navy “equally strong as England’s,”54 he nonetheless had built a force which quite overawed the rival fleets of France or Russia.

有关德国扩张主义的重点是,要么这个国家已拥有改变现状的实力手段,要么它已拥有创造这种手段的物资资源。关于这种能力的最明显的说明,是1898年之后德国迅速建设海军,其海军的规模在蒂尔皮茨的领导下从世界的第六位变为仅次于英国的帝国海军。到大战前夕,由13艘无畏级战列舰、16艘旧式战列舰和5艘战列巡洋舰组成的这支公海舰队,成为一支迫使英国海军部逐渐把驻扎在海外的主力舰队撤往北海的强大力量;那时有迹象(较好的内部结构、炮弹、光学设备、舰炮控制、夜间训练等)表明,德国舰船从整体上来说比较优良。虽然蒂尔皮茨一直未能得到大量资金以实现其最终创建一支“同英国一样强大”的舰队的目标,但他确实建立了一支足以威慑敌对的法国和俄国舰队的力量。

Germany’s capacity to fight successfully on land seemed to some observers less impressive; indeed, at first sight, the Prussian army in the decade before 1914 appeared eclipsed by the far larger forces of czarist Russia, and matched by those of France. But such appearances were deceptive. For complex domestic-political reasons, the German government had opted to keep the army to a certain size and to allow Tirpitz’s fleet substantially to increase its share of the total defense budget. 55 When the tense international circumstances of 1911 and 1912 caused Berlin to decide upon a large-scale expansion of the army, the swift change of gear was imposing. Between 1910 and 1914, its army budget rose from $204 million to $442 million, whereas France’s grew only from $188 million to $197 million—and yet France was conscripting 89 percent of its eligible youth compared with Germany’s 53 percent to achieve that buildup. It was true that Russia was spending some $324 million on its army by 1914, but at stupendous strain; defense expenditures consumed 6. 3 percent of Russia’s national income, but only 4. 6 percent of Germany’s. 56 With the exception of Britain, Germany bore the “burden of armaments” more easily than any other European state. Furthermore, while the Prussian army could mobilize and equip millions of reservists and—because of their better education and training—actually deploy them in front-line operations, France and Russia could not. The French general staff held that their reservists could only be used behind the lines;57 and Russia possessed neither the weapons, boots, and uniforms to equip its theoretical reserve army of millions nor the officers to supervise them. But even this does not probe the full depths of the German military capacity, which was also reflected in such unquantifiable factors as good internal lines of communication, faster mobilization schedules, superior staff training, advanced technology, and so on.

对某些观察家来说,德国成功地在陆上作战的能力给人的印象不那么深刻;的确,乍一看,在1914年前的10年里,普鲁士军队与规模大得多的沙俄军队相比就相形见绌了,而法国的军队也和它差不多。但这种表象容易使人误解。由于复杂的国内政治原因,德国政府选择了把它的军队维持在一定的规模上,并允许蒂尔皮茨的舰队大量增加其在整个国防预算中的份额。当1911年和1912年的国际紧张局势导致柏林决定大规模发展其陆军时,装备上的迅速变化是很明显的。从1910年到1914年,其陆军的预算从2.04亿美元增至4.42亿美元,而法国只从1.88亿美元增至1.97亿美元——但法国把89%的适龄青年征召入伍,而德国只招募了53%的适龄青年就实现了这种军事动员。到1914年,俄国已为其陆军花费了3.24亿美元,但却甚感紧张:国防开支占俄国国民收入的6.3%,而德国的只占4.6%。除英国之外,德国比欧洲其他任何国家更容易承受“武装的重负”。此外,当普鲁士军队能够动员和装备数百万后备役军人,而且——由于其更好的教育和训练——实际上能把它们部署在前线采取行动时,法国和俄国却不能。法国总参谋部坚持认为,其后备役军人只能在后方使用;而俄国既没有武器、靴子和军服来装备其数百万理论上存在的后备军,也无军官来管理他们。但即使如此,也仍未弄清德国军事能力究竟达到了什么程度,因为它还反映在诸如良好的国内交通线、快速的动员体制、优良的参谋训练、先进的技术等不能用数量来表达的因素上。

But the German Empire was weakened by its geography and its diplomacy. Because it lay in the center of the continent, its growth appeared to threaten a number of other Great Powers simultaneously. The efficiency of its military machine, coupled with Pan-German calls for a reordering of Europe’s boundaries, alarmed both the French and the Russians and drove them closer to each other. The swift expansion of the German navy upset Britain, as did the latent German threat to the Low Countries and northern France. Germany, in one scholar’s phrase, was “born encircled. ”58 Even if German expansionism was directed overseas, where could it go without trespassing upon the spheres of influence of other Great Powers? A venture into Latin America could only be pursued at the cost of war with the United States. Expansion in China had been frowned upon by Russia and Britain in the 1890s and was out of the question after the Japanese victory over Russia in 1905. Attempts to develop the Baghdad Railway alarmed both London and St. Petersburg. Efforts to secure the Portuguese colonies were checked by the British. While the United States could apparently expand its influence in the western hemisphere, Japan encroach upon China, Russia and Britain penetrate into the Middle East, and France “round off” its holdings in northwestern Africa, Germany was to go empty-handed. When Bülow, in his famous “hammer or anvil” speech of 1899, angrily declared, “We cannot allow any foreign power, any foreign Jupiter to tell us: ‘What can be done? The world is already partitioned,’ ” he was expressing a widely held resentment. Little wonder that German publicists called for a redivision of the globe. 59

但德意志帝国被它的地理环境和外交削弱了。因为它位于欧洲大陆的中心,它的发展似乎要同时威胁到许多其他大国。其军事机器的效能,再加上泛德意志重组欧洲边界的号召,使法国和俄国感到恐慌,迫使它们彼此之间更为接近。德国海军的迅速发展使英国感到极度不安,就像德国对低地国家和法国北部的潜在威胁一样。用一位学者的话来说,德国“天生就被包围住了”。即使德国的扩张是指向海外的,但如不侵入其他大国的势力范围,又能到哪里去呢?向拉丁美洲冒险只能以与美国进行战争为代价。19世纪90年代,它在中国的扩张一直遭到俄国和英国的反对,而且当1905年日本人取得对俄战争的胜利后就成为不可能的了。建造巴格达铁路的企图使伦敦和圣彼得堡都感到惊恐不安。想把葡萄牙殖民地搞到手的努力受到了英国人的阻拦。当美国可以明目张胆地在西半球扩大自己的势力,日本侵入中国,俄国和英国向中东渗透,法国“完善”其在非洲西北部的据点时,德国却两手空空。当比洛在其1899年著名的《锤子或铁砧》的演说中愤怒地宣称“我们不能允许任何外国或任何外国的朱庇特神来告诉我们‘能做什么呢?世界已经被瓜分完毕’”时,他表达了一种普遍存在的不满情绪。没有什么人对德国的宣传家们重新分割世界的呼吁感到疑惑不解。

To be sure, all rising powers call for changes in an international order which has been fixed to the advantage of the older, established powers. 60 From a Realpolitik viewpoint, the question was whether this particular challenger could secure changes without provoking too much opposition. And while geography played an important role here, diplomacy was also significant; because Germany did not enjoy, say, Japan’s geopolitical position, its statecraft had to be of an extraordinarily high order. Realizing the unease and jealousy which the Second Reich’s sudden emergence had caused, Bismarck strove after 1871 to convince the other Great Powers (especially the flank powers of Russia and Britain) that Germany had no further territorial ambitions. Wilhelm and his advisers, eager to show their mettle, were much less careful. Not only did they convey their dissatisfaction with the existing order, but—and this was the greatest failure of all—the decision-making process in Berlin concealed, behind a facade of high imperial purpose, a chaos and instability which amazed all who witnessed it in close action. Much of this was due to the character weaknesses of Wilhelm II himself, but it was exacerbated by institutional flaws in the Bismarckian constitution; with no body (like a cabinet) collectively possessing responsibility for overall government policy, different departments and interest groups pursued their aims without any check from above or ordering of priorities. 61 The navy thought almost solely of a future war with England; the army planned to eliminate France; financiers and businessmen wished to move into the Balkans, Turkey, and the Near East, eliminating Russian influence in the process. The result, moaned Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg in July 1914, was to “challenge everybody, get in everyone’s way and actually, in the course of all this, weaken nobody. ”62 This was not a recipe for success in a world full of egoistic and suspicious nation-states.

可以肯定的是,所有正在崛起的大国都呼吁改变已经固定下来的对旧的、老资格的大国有利的国际秩序。从强权政治的观点来看,问题是这种特殊的挑战是否能在不招致太多反对的情况下改变旧的国际秩序。地理环境发挥着重要作用,外交也很重要;也就是说,因为德国没有日本那样的地缘政治形势,它治国的本领就需要有非常高的水平。由于已认识到第二帝国的突然出现引起了不安和妒忌,俾斯麦在1871年之后一直努力使其他大国(特别是侧翼国家俄国和英国)相信德国没有进一步的领土野心。但是急于表明其气概的威廉及其顾问们太不谨慎了,他们不仅公开表示对现存秩序不满,而且——这是最大的失败——柏林的决策过程表明,隐藏在帝国重要目的表象后面的是混乱和不稳定,这使所有目睹在机密行动中这一过程的人感到吃惊。这种情况有许多应归咎于威廉二世个人的性格弱点,但它被俾斯麦宪法制度上的缺陷加剧了。由于没有任何人(像一个内阁一样)对政府的全面政策集体负责,不同的部门和利益集团都去追求它们自己的目标,上边对此不作任何检查,也不规定哪是重点。海军只考虑将来同英国的战争;陆军的计划是消灭法国;金融家和商人们则希望进入巴尔干、土耳其和近东,并在此过程中消除俄国的势力。首相贝特曼·霍尔维格在1914年7月悲叹道,结果将是“向每一方挑战,又妨碍了每一方,而且在所有这些进程中实际上削弱不了任何一方”。在一个充满自私自利并疑虑重重的国家里,这不是一个成功的窍门。

Finally, there remained the danger that failure to achieve diplomatic or territorial successes would affect the delicate internal politics of Wilhelmine Germany, whose Junker elite worried about the (relative) decline of the agricultural interest, the rise of organized labor, and the growing influence of Social Democracy in a period of industrial boom. It was true that after 1897 the pursuit of Weltpolitik was motivated to a considerable extent by the calculation that this would be politically popular and divert attention from Germany’s domestic-political fissures. 63 But the regime in Berlin always ran the dual risk that if it backed down from a confrontation with a “foreign Jupiter,” German nationalist opinion might revile and denounce the Kaiser and his aides; whereas, if the country became engaged in an all-out war, it was not clear whether the natural patriotism of the masses of workers, soldiers, and sailors would outweigh their dislike of the archconservative Prusso-German state. While some observers felt that a war would unite the nation behind the emperor, others feared it would further strain the German sociopolitical fabric. Again, this needs to be placed in context—for example, German internal weaknesses were hardly as serious as those in Russia or Austria-Hungary, but they did exist, and they certainly could affect the country’s ability to engage in a lengthy “total” war.

最后,仍存在一种危险:如不能在外交上和领土上获得成功,将影响威廉德国微妙的国内政治,威廉的容克上层担忧其农业利益会(相对)减少,担心有组织的工人的兴起和工业繁荣时期社会民主党影响的发展。1897年以后,对强权政治的追求确实在很大程度上受到了这些考虑的推动,这将在政治上受到欢迎并转移对德国国内的政治分歧的注意力。但柏林的政权通常要冒双重危险:如果它在与“外国朱庇特”的对峙中退却,德国的民族主义势力可能会谩骂和谴责这位皇帝及其助手们;而如果国家全力参加一场战争,却又不清楚广大工人群众、士兵和水兵们自发的爱国主义是否将超过他们对非常保守的普鲁士—德意志国家的厌恶。当一些观察家认为一场战争将使全国团结起来支持皇帝时,其他人则担心它将进一步加剧德国社会政治结构的紧张状况。还有,这需要在各方面联系起来看,例如,德国国内的弱点不像俄国或奥匈帝国的弱点那么明显,但确实存在,而且它们肯定会影响这个国家参加一场长期的“总体战争”的能力。

It has been argued by many historians that imperial Germany was a “special case,” following a Sonderweg (“special path”) which would one day culminate in the excesses of National Socialism. Viewed solely in terms of political culture and rhetoric around 1900, this is a hard claim to detect: Russian and Austrian anti- Semitism was at least as strong as German, French chauvinism as marked as the German, Japan’s sense of cultural uniqueness and destiny as broadly held as Germany’s. Each of the powers examined here was “special,” and in an age of imperialism was all too eager to assert its specialness. From the criterion of power politics, however, Germany did possess unique features which were of great import. It was the one Great Power which combined the modern, industrialized strength of the western democracies with the autocratic (one is tempted to say irresponsible) decision-making features of the eastern monarchies. 64 It was the one “newcomer” Great Power, with the exception of the United States, which really had the strength to challenge the existing order. And it was the one rising Great Power which, if it expanded its borders farther to the east or to the west, could only do so at the expense of powerful neighbors: the one country whose future growth, in Calleo’s words, “directly” rather than “indirectly” undermined the European balance. 65 This was an explosive combination for a nation which felt, in Tirpitz’s phrase, that it was “a life-and-death question … to make up the lost ground. ”66

许多历史学家争辩说,德意志帝国“情况特殊”,它遵循的是有朝一日将在国家社会主义的暴行中达到顶点的“特殊道路”。只从1900年前后的政治文化和花言巧语来看,这是一个很难检验的主张:俄国和奥地利的反犹主义至少与德国一样强烈,法国的沙文主义与德国的一样明显,日本对文化的独特性和天定命运的观念与德国持有的一样广泛。这些被观察的每一个大国都是“特殊的”,它们在帝国主义时代都太急于宣称其特殊性了。但从强权政治的标准来看,德国确实具有很重要的特性。它是一个把西方民主国家的现代化、工业化的力量,与东方君主国专断的(也有人可能说是不负责任的)决策结合在一起的大国。它是除美国之外“新出现的”大国,它的确有能力向现存秩序挑战。它是一个正在崛起的大国,如果它进一步向东或向西扩大它的边界,只能损害其强大的邻国的利益:用卡利奥的话来说,这个国家将来的发展会“直接”而不是“间接”地动摇欧洲的均势。按照蒂尔皮茨的说法,德国认为“弥补其失去的地盘……是一个生死存亡的问题”,对这样一个国家来说,这是一个爆炸性的结合。

It seemed a vital matter to the rising states to break through, but it was even more urgent for those established Great Powers now under pressure to try to hold their own. Here again, it will be necessary to point to the very significant differences between the three Powers in question, Austria-Hungary, France, and Britain—and perhaps especially between the first-named and the last. Nonetheless, the charts of their relative power in world affairs would show all of them distinctly weaker by the end of the nineteenth century than they had been fifty or sixty years earlier,67 even if their defense budgets were larger and their colonial empires more extensive, and if (in the case of France and Austria-Hungary) they still had territorial ambitions in Europe. Furthermore, it seems fair to claim that the leaderships within these nations knew the international scene had become more complicated and threatening than that which their predecessors had faced, and that such knowledge was forcing them to consider radical changes of policy in an effort to meet the new circumstances.

对于一个要进行突破的正在崛起的国家来说,这似乎是一个至关重要的问题,而对于那些在目前的压力之下要努力据守自己地盘的老资格的大国来说,这个问题更为迫切。这里有必要再次指出三个正在被谈论的大国——奥匈帝国、法国和英国之间的重要差别,特别是奥匈帝国和最后一个英国之间的差别。但是,有关它们在世界事务中各自力量的图表将表明,它们在19世纪末与它们在50或60年前相比,都明显变弱了,虽然它们的防务预算更多,殖民帝国的版图更大,而且它们(就法国和奥匈帝国来说)在欧洲还有领土野心。不仅如此,指出下面这一点似乎是公平的:这些国家的领导人都知道,与他们的前任相比,国际形势变得更加复杂,险象丛生,而这种认识正迫使他们考虑彻底改变政策,以努力适应新的形势。

Austria-Hungary

奥匈帝国

Although the Austro-Hungarian Empire was by far the weakest of the established Great Powers—and, in Taylor’s words, slipping out of their ranks68—this is not obvious from a glance at the macroeconomic statistics. Despite considerable emigration, its population rose from 41 million in 1890 to 52 million in 1914, to go well clear of France and Italy, and some way ahead of Britain. The empire also underwent much industrialization in these decades, though the pace of change was perhaps swifter before 1900 than after. Its coal production by 1914 was a respectable 47 million tons, higher than either France’s or Russia’s, and even in its steel production and energy consumption it was not significantly inferior to either of the Dual Alliance powers. Its textile industry experienced a surge in output, brewing and sugar-beet production rose, the oilfields of Galicia were exploited, mechanization occurred on the estates of Hungary, the Skoda armaments works multiplied in size, electrification occurred in the major cities, and the state vigorously promoted railway construction. 69 According to one of Bairodas calculations, the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s GNP in 1913 was virtually the same as France’s,70 which looks a little suspect—as does Farrar’s claim that its share of “European power” rose from 4. 0 percent in 1890 to 7. 2 percent in 1910. 71 Nonetheless, it is clear that the empire’s growth rates from 1870 to 1913 were among the highest in Europe, and that its “industrial potential” was growing faster even than Russia’s. 72

虽然奥匈帝国是已经确立的强国中最弱的一个(用泰勒的话来说,它正在从强国的行列中悄悄消失),但是这一点从宏观的经济统计数字来看并不明显。尽管大量地向外移民,它的人口仍然从1890年的4100万上升到1914年的5200万,远远超过了法国和意大利,在某种程度上也超过了英国。在这几十年里,帝国实现了高度工业化,其经济发展速度,在1900年以前可能比以后更快。到1914年,它的煤产量已相当可观,达到4700万吨,既高于法国,也高于俄国。甚至在钢产量和能源消耗方面,它也绝不比这两个协约国中的任何一国差。它的纺织工业产量经历了历史上的一个高峰期,酿酒和甜菜的产量也有所提高。加利西亚的油田已被开采,庄园实现了机械化。斯科达兵工厂的规模成倍扩大,主要城市正实现电气化,铁路建设在国家的促进下蓬勃发展。根据贝洛克的一项统计,奥匈帝国1913年的国民生产总值实际上与法国相同,这看起来有些值得怀疑——就像法勒公布的材料一样可疑,该材料说,1890年它在“欧洲强国”中所占的比例为4%,到1910年上升到7.2%。然而,很明显,奥匈帝国从1870年到1913年的增长率在欧洲属于最高之列,它的“工业潜力”的增长速度甚至比俄国更快。

Once one examines Austria-Hungary’s economy and society in more detail, however, significant flaws appear. Perhaps the most fundamental of these was the enormous regional differences in per capita income and output, which to a large degree mirrored socioeconomic and ethnic diversities in a territory stretching from the Swiss Alps to the Bukovina. It was not merely the fact that in 1910 73 percent of the population of Galicia and Bukovina were employed in agriculture compared with 55 percent for the empire as a whole; much more significant and alarming was the enormous disparity of wealth, with per capita income in Lower Austria (850 crowns) and Bohemia (761 crowns) being far in excess of those in Galicia (316 crowns), Bukovina (310 crowns), and Dalmatia (264 crowns). 73 Yet while it was in the Austrian provinces and Czech lands that industrial “takeoff” was occurring, and in Hungary that agricultural improvements were under way, it was in those povertystricken Slavic regions that the population was increasing the fastest. In consequence, Austria-Hungary’s per capita level of industrialization remained well below that of the leading Great Powers, and despite all the absolute increases in output, its share of world manufacturing production hovered around a mere 4. 5 percent in those decades. This was not a strong economic base on which a country with Austria-Hungary’s strategical tasks could rest.

但是,一旦更加细致地考察奥匈帝国的经济和社会状况,就会发现它存在着重大的缺陷。其中最基本的缺陷可能是人均收入和产量存在着巨大的地区性差异,这在很大程度上反映了从瑞士阿尔卑斯山到布科维纳地区的社会经济和种族差异,还反映了下述的鲜明差距:1910年,加利西亚和布科维纳73%的人口从事农业,而整个帝国55%的人口从事农业;更主要、更令人惊异的是财富的巨大的不均,下奥地利(850克朗)和波希米亚(761克朗)的人均收入,远远超过加利西亚(316克朗)、布科维纳(310克朗)和达尔马提亚(264克朗)。还有,在奥地利行省和捷克土地上工业正在起飞、匈牙利农业改良正在进行的同时,被贫穷困扰的斯拉夫地区,人口正以最快的速度增长着。结果使奥匈帝国工业化的人均水平远低于其他主要强国。在这几十年中,尽管它所有产品产量都有了绝对增长,但它在世界制造业生产的总产量中所占的比例仍然徘徊在4.5%左右。对肩负着战略任务的奥匈帝国来说,它所依靠的经济基础并不是强大的。

This relative backwardness might have been compensated for by a high degree of national-cultural cohesion, such as existed in Japan or France; but, alas, Vienna controlled the most ethnically diverse cluster of peoples in Europe74—when war came in 1914, for example, the mobilization order was given in fifteen different languages. The age-old tension between German speakers and Czech speakers in Bohemia was not the most serious of the problems facing Emperor Francis Joseph and his advisers, even if the “Young Czech” movement was making it sound so. The strained relations with Hungary, which despite its post-1867 status as an equal partner clashed with Vienna again and again over such issues as tariffs, treatment of ethnic minorities, “Magyarization” of the army, and so on, were such that by 1899, western observers feared the breakup of the entire empire and the French foreign minister, Delcassé, secretly renegotiated the terms of the Dual Alliance with Russia in order to prevent Germany from succeeding to the Austrian lands and access to the Adriatic coast. By 1905, indeed, the general staff in Vienna was quietly preparing a contingency plan for the military occupation of Hungary should the crisis worsen. 75 Vienna’s list of nationality problems did not stop with the Czechs and the Magyars. The Italians in the south resented the stiff Germanization in their territories, and looked over the border for help from Rome—as the captive Rumanians, to a lesser degree, looked eastward to Bucharest. The Poles, by contrast, were quiescent, in part because the rights they enjoyed under the Habsburg Empire were superior to those obtaining in the German- and Russian-dominated territories. But by far the largest danger to the unity of the empire came from the South Slavs, since dissident groups within seemed to be looking toward Serbia and, more distantly, toward Russia. Compromises with South Slav aspirations were urged from time to time, by more liberal circles in Vienna, but they were fiercely resisted by the Magyar gentry, who both opposed any diminution of Hungary’s special status and also kept up their strong discrimination of ethnic minorities within Hungary itself. Since a political solution of this issue was denied to the moderates, the door was open for Austro- German nationalists like the chief of staff, General Conrad, to argue that the Serbs and their sympathizers should be dealt with by force. Despite the restraint exercised by Emperor Francis Joseph himself, this always remained a last resort if the Empire’s survival did really seem to be threatened.

存在于日本和法国的那种民族文化高度的内聚力,对于民族关系相当复杂的奥匈帝国来说反而成了不良因素。维也纳控制着欧洲最众多的民族——当1914年大战来临时,动员令要以15种不同的民族语言下达。在波希米亚地区说德语和说捷克语的人之间由来已久的紧张关系,并不是弗朗西斯·约瑟夫皇帝及其顾问们所面临的最严重的问题。虽然“青年捷克”运动给这种紧张关系蒙上了最严重的阴影,虽然匈牙利在1867年以后获得了与之同等的伙伴地位,它还是免不了就诸如关税、少数民族的待遇、军队的“匈牙利化”等问题不断地与维也纳发生冲突,双方的关系达到了一触即发的紧张程度,以至于到1899年西方的观察家们曾经担心整个帝国就要崩溃。法国外长德尔卡塞为此曾秘密地与俄国重新商谈结成两国联盟的条件,目的在于防止德国接管奥地利领地和占有亚得里亚海岸。到1905年,维也纳的总参谋部确实在悄悄地准备着应急计划,以便在危机恶化时对匈牙利实行军事占领。维也纳所遇到的民族问题,不仅仅是捷克人和匈牙利人的问题,而且南部的意大利人也反对在他们的土地上强行德意志化,并寄望于边界那边,企求罗马的援助——就像被控制的罗马尼亚人在较小的程度上求助于东部的布加勒斯特一样。相比之下,波兰人比较平静,其部分原因是他们在奥匈帝国统治之下比在德国和俄国统治的区域享有比较优越的权利。但是,迄今对帝国联合体的最大威胁来自南部的斯拉夫人,因为帝国内部持不同政见的集团似乎寄希望于塞尔维亚,甚至更远处的俄国。在维也纳,自由主义人士时常敦促政府向南部的斯拉夫人的要求进行妥协,但匈牙利贵族强烈反对这些妥协。他们既反对匈牙利特殊的地位受到任何削弱,同时又在匈牙利境内对少数民族大加歧视。由于温和主义者要求对这一问题实行政治解决的办法遭到了政府的拒绝,这就为总参谋长康拉德将军之流的奥地利—德意志民族主义者打开了方便之门。他们坚持以武力对付塞尔维亚人及其同情者。这一主张虽然遭到了弗朗西斯·约瑟夫皇帝本人的阻止,但是如果帝国的生存真正受到了威胁,它仍不失为一项最后解决问题的有效办法。

All of this undoubtedly effected Austria-Hungary’s power, and in a whole number of ways. It was not that multi-ethnicity inevitably meant military weakness. The army remained a unifying institution, and extraordinarily adept at using a whole array of languages of command; nor had its old skills of divide and rule been forgotten when it came to garrisons and deployments. But it was increasingly difficult to rely upon the wholehearted cooperation of the Czech or Hungarian regiments in certain circumstances, and even the traditional loyalty of the Croats (used for centuries along the “military border”) was eroded by Hungarian persecution. What was more, Vienna’s classic answer to all of these particularist grievances was to smother them with committees, with new jobs, tax concessions, additional railway branch lines, and so on. “There were, in 1914, well over 3,000,000 civil servants, running things as diverse as schools, hospitals, welfare, taxation, railways, posts, etc. … so … that there was not much money left for the army itself. ”76 According to Wright’s figures, defense appropriations took a far smaller share of “national (i. e. , central government) appropriations” in the Austria- Hungarian Empire than in any of the other Great Powers. 77 In consequence, while its fleet never had enough funds to match even the Italian, let alone the French, navy in the Mediterranean, allocations to the army were between one-third and onehalf of those which the Russian and Prussian armies enjoyed. The army’s weapons, especially artillery, were out-of-date and far too few. Because of lack of funds, only about 30 percent of the available manpower was conscripted, and many of them were sent on “permanent leave” or received only eight weeks training. It was not a system geared to produce masses of competent reserves in wartime. 78

所有这些无疑在很多方面影响了奥匈帝国的实力,这并不是说众多的民族一定意味着军事上的脆弱。帝国军队保持了统一的组织,善于使用多种语言的指挥系统,以及在驻防和部署兵力时惯用的分而治之的手法。但是,在某种情况下,依靠捷克或匈牙利部队的合作日益困难,甚至克罗地亚人(几个世纪以来用于“军事边界”地带)传统的忠诚也被匈牙利人的迫害所腐蚀。而且维也纳对付这些地区利益主义者的不满的一贯反应是,用设立专门问题委员会、提供新的工作、减免税收、增加铁路支线等办法来加以遏制。“在1914年,文职公务员的人数超过300万,他们管理学校、医院、社会福利、税收、铁路、邮电等各种各样的事务……于是……没有充足的钱留给军队。”根据赖特的统计,奥匈帝国的国防拨款在“国家(即中央政府)拨款”中所占的比例,比其他任何强国都少得多。结果它的舰队从来也没有充足的资金以赶上意大利,更不用说在地中海的法国海军了。军队的给养也只有俄国和普鲁士军队所享有的1/3到一半左右。军队的武器,特别是火炮已经过时,而且数量有限。由于缺乏资金,只有可征用人力的30%应征入伍,他们之中的大部分被放了长假,或只受到8周的训练。这种制度难以造就战时大量合格的后备军。

As the international tensions built up in the decade or so after 1900, the Austro- Hungarian Empire’s strategical position appeared parlous indeed. Its internal divisions threatened to split the country asunder, and complicated relations with most of its neighbors. Its economic growth, although marked, was not allowing it to catch up with leading Great Powers such as Britain and Germany. It spent less per capita on defense than many of the other powers, and it conscripted a far smaller ratio of its eligible youth into the army than any of the continental nations. To cap it all, it seemed to have so many possible foes that its general staff had to plan for a whole variety of campaigns—a complication which very few of the other Great Powers were distracted with.

1900年以后约10年时间里,国际紧张局势加剧,奥匈帝国的战略地位越发岌岌可危,内部分裂使国家面临分崩离析的威胁,同时使它与大多数邻国的关系复杂起来。经济的增长虽然显著,但它却无法赶上英、德这些主要强国。它用在国防上的人均费用比许多其他强国要少,应征入伍的青年在适龄青年中所占的比例,比其他任何大陆国家都少得多。最后再加上它似乎有很多的潜在的敌人,结果帝国总参谋部不得不为众多的战役制订计划——这是其他国家很少在上面分散精力的麻烦事。

That the Austro-Hungarian Empire had so many potential enemies was itself due to its unique geographical and multinational situation. Despite the Triple Alliance, the tensions with Italy became greater after 1900, and on several occasions Conrad advocated a military blow against this southern neighbor; even if his proposal was firmly rejected by both the foreign ministry and the emperor, the garrisons and fortresses along the Italian frontier were steadily built up. Much farther afield, Vienna had to worry about Rumania, which by 1912 became a distinct threat as it moved into the opposite camp. But the country which attracted the most venom was Serbia, which, with Montenegro, seemed a magnet to the South Slavs within the empire and thus a cancerous growth which had to be eliminated. The only problem with that agreeable solution was that an attack upon Serbia could well provoke a military response from Austria-Hungary’s most formidable rival, czarist Russia, which would invade the northeastern front just as the bulk of the Austro-Hungarian army was pushing southward, past Belgrade. Although even the hyperbelligerent Conrad asserted that it was “up to the diplomats”79 to keep the empire from having to fight all these foes at once, his own pre-1914 war plans reveal the fantastic military juggling act for which the army had to prepare. While a main force (AStaffel) of nine army corps would be prepared for deployment against either (!) Italy or Russia, a smaller group of three army corps would be mobilized against Serbia- Montenegro (Minimalgruppe Balkan). In addition, a strategic reserve of four army corps (B-Staffel) would hold itself ready “either to reinforce A-Staffel and make it into a powerful offensive force, or, if there were no danger from either Italy or Russia, to join Minimalgruppe Balkan for an offensive against Serbia. ”80

奥匈帝国有如此之多的潜在敌人,是由于它本身独特的地理位置和多民族的国情造成的。虽然有三国联盟,但同意大利的关系在1900年以后变得更加紧张。康拉德在某些场合鼓吹向这个南方邻国发动军事进攻,尽管他的意见遭到了外交大臣和皇帝的强烈反对,但是沿着意大利边境的驻军和要塞仍然在不断加强。再扯远一点,罗马尼亚也在使维也纳感到不安,因为在1912年,罗马尼亚已经加入了敌对阵营,这对它构成了明显的威胁。但是最有敌意的地区是塞尔维亚,它与门的内哥罗一道似乎是帝国内吸引南部斯拉夫人的一块磁铁,因此帝国必须除掉这一病患。恰当的解决办法所带来的唯一问题是,对塞尔维亚的进攻很可能会引起奥匈帝国最可怕的敌人——沙皇俄国的军事反应,它很可能会在奥匈帝国的大批军队经过贝尔格莱德向南挺进时,入侵东北边境。因此,最好战的康拉德声称,“将通过外交家”使帝国避免同时向所有的敌人开战。他1914年制订的战争计划中,暴露了军队不得不准备进行军事玩火行动。当由几个军组成的主力部队(A梯队)做好了战斗部署,准备去对付意大利或俄国时,一个由3个军组成的较小的集团军(巴尔干小分队)将被动员去进攻塞尔维亚—门的内哥罗。此外,一个由4个军(B梯队)组成的战略预备部队,将随时准备增援A梯队,使之变成一支强大的进攻力量,如果没有来自意大利或俄国的危险,就加入巴尔干小分队进攻塞尔维亚。

“The heart of the matter,” it has been said, “was simply that Austria-Hungary was trying to act the part of a great power with the resources of a second-rank one. ”81 The desperate efforts to be strong on all fronts ran a serious risk of making the empire weak everywhere; at the very least, they placed superhuman demands upon the empire’s railway system, and upon the staff officers who would control it. More than that, these operational dilemmas confirmed what most observers in Vienna had reluctantly accepted since 1870: that in the event of a Great Power war, Austria- Hungary needed German support. This would not be the case in a purely Austro- Italian war (although that, despite Conrad’s frequent fears, was the least likely contingency); but German military assistance certainly would be required if Austria- Hungary became embroiled in a war with Serbia, and the latter was then aided by Russia; hence the repeated attempts by Conrad prior to 1914 to secure Berlin’s assurances on this point. Finally, the baroque nature of this operational planning reflects once again what many contemporaries could see but some later historians have declined to admit:82 that if the nationalist explosions of discontent in the Balkans, and in the empire itself, continued to go off, the chances of preserving Kaiser Joseph’s unique but anachronistic inheritance were well-nigh impossible. And when that happened, the European equilibrium was bound to be undermined.

有人认为,“问题的核心在于奥匈帝国企图以二流国家的物力扮演一流强国的角色”,企图在各条战线上都强大起来。这种不顾一切的努力,使帝国出现了到处衰落的严重风险。至少,这些努力给帝国的铁路系统及控制它的官员提出了不切实际的要求。不仅如此,这种军事上的进退维谷证实了维也纳大多数观察家自1870年以来不愿接受的事实:一旦大国战争爆发,奥匈帝国就需要德国的援助。如果只是纯粹的奥意战争(虽然它是最不可能的危急事件,尽管康拉德时常担心),情况可能还不致如此。但是奥匈帝国卷入塞尔维亚的战争,塞尔维亚人因此得到俄国的援助,那么德国的军事援助肯定是必需的。因此在1914年以前,康拉德为使柏林保证在这一问题上的许诺而进行了不懈的努力。最后,这种军事计划的荒诞性又一次反映了很多当代人能观察到但后来的某些历史学家又不愿承认的事实:如果在巴尔干和帝国本土内部爆发的民族主义不满情绪继续激化,那么维护约瑟夫皇帝所独有的但又不合时代潮流的继承权几乎是不可能的。当这样的事情发生时,欧洲的均势注定要被打破。

France

法国

France in 1914 possessed considerable advantages over Austria-Hungary. Perhaps the most important was that it had only one enemy, Germany, against which its entire national resources could be concentrated. This had not been the case in the late 1880s, when France was challenging Britain in Egypt and West Africa and engaged in a determined naval race against the Royal Navy, quarreling with Italy almost to the point of blows, and girding itself for the revanche against Germany. 83 Even when more cautious politicians drew the country back from the brink and then moved into the early stages of their alliance with Russia, the French strategical dilemma was still an acute one. Its most formidable foe, clearly, was the German Empire, now more powerful than ever. But the Italian naval and colonial challenge (as the French viewed it) was also disturbing, not only for its own sake, but because a war with Italy would almost certainly involve its German ally. For the army, this meant that a considerable number of divisions would have to be stationed in the southeast; for the navy, it exacerbated the age-old strategical problem of whether to concentrate the fleet in Mediterranean or Atlantic ports or to run the risk of dividing it into two smaller forces. 84

1914年,法国具有比奥地利远为有利的条件,其中最主要的是它只有一个敌人——德国。它可以集中国家的全部力量对付德国。可是在19世纪80年代后期,情况并非如此,那时法国在埃及和西非向英国挑战,并与英国皇家海军展开军备竞赛。同意大利的纠纷也几乎达到了大动干戈的程度。与此同时,它还准备向德国进行报复。甚至当较为谨慎的政治家们把国家从战争边缘上拉回来,然后进入与俄国结盟的早期阶段时,法国面临的战略困境仍然很严重。它的最可怕的敌人德意志帝国,现在显然比以往更强大了。但是,意大利的海军和在殖民扩张方面的挑战(如法国人所见)也是令人不安的。这不仅是由于意大利自身的缘故,而且同意大利进行战争几乎肯定会使它的盟国德国卷进来。对于法国陆军来说,这意味着它将不得不把大量的师驻守在其东南边境。对海军来说,一个老的战略问题变得更加棘手:它是把舰队集中在地中海港口还是大西洋的港口,还是冒险将舰队分成两支较小的兵力?

All this was compounded by the swift deterioration in Anglo-French relations which followed the British occupation of Egypt in 1882. From 1884, the two countries were locked into an escalating naval race, which on the British side was associated with the possible loss of their Mediterranean line of communications and (occasionally) with fears of a French cross-Channel invasion. 85 Even more persistent and threatening were the frequent Anglo-French colonial clashes. Britain and France had quarreled over the Congo in 1884–1885 and over West Africa throughout the entire 1880s and 1890s. In 1893 they seemed to be on the brink of war over Siam. The greatest crisis of all came in 1898, when their sixteen-year rivalry over control of the Nile Valley climaxed in the confrontation between Kitchener’s army and Marchanda small expedition at Fashoda. Although the French backed down on that occasion, they were energetic and bold imperialists. Neither the inhabitants of Timbuktu nor those of Tonkin would have regarded France as a power in decline, far from it. Between 1871 and 1900, France had added 3. 5 million square miles to its existing colonial territories, and it possessed indisputably the largest overseas empire after Britain’s. Although the commerce of those lands was not great, France had built up a considerable colonial army and an array of prime naval bases from Dakar to Saigon. Even in places which France had not colonized, such as the Levant and South China, its influence was large. 86

所有这些都因1882年英国占领埃及以后,英法关系的迅速恶化而复杂起来。从1884年起,两国暗地里进行着逐渐升级的海军军备竞赛,对英国来说,军备竞赛与以下的前景有关:它有丧失地中海交通线的可能,(偶尔)还担心法国会越过英吉利海峡入侵英国。更持久更具威胁的是英法之间关于殖民地的不断冲突。在1884年至1885年,英法为争夺刚果发生争吵;在整个19世纪80年代和90年代,两国为争夺西非闹得不可开交;1893年为争夺泰国,它们几乎处于战争边缘。最大的危机出现于1898年,当时双方为争夺尼罗河流域的控制权进行了长达16年之久的对抗,基切纳的军队与马尔尚的小分队在法绍达的冲突使对抗达到顶点。虽然当时法国人退让了,但他们仍是精力旺盛、胆大妄为的帝国主义者。廷巴克图[4]和东京[5]的居民无人认为作为强国的法国正在衰落。1871~1900年,法国殖民地领土又增加了350万平方英里,它无可争辩地成为仅次于英国的最大的海外殖民帝国。虽然那些地区的商业不很发达,法国仍在从达喀尔到西贡之间的广大范围内建立起了庞大的殖民地军队和一些优良的海军基地。即使在没有进行殖民化的地区,如地中海东部沿岸以及中国南部,它的影响也很大。

France had been able to carry out such a dynamic colonial policy, it has been argued, because the structures of government had permitted a small group of bureaucrats, colonial governors, and parti colonial enthusiasts to effect “forward” strategies which the fast-changing ministries of the Third Republic had little chance to control. 87 But if the volatile state of French parliamentary politics had inadvertently given a strength and consistency to its imperial policy—by placing it in the hands of permanent officials and their friends in the colonial “lobby”— it had a far less happy impact upon naval and military affairs. For example, the swift changes of regime brought with them new ministers of marine, some of whom were mere “placemen,” others of whom had strongly held (but always varying) opinions on naval strategy. In consequence, although large sums were allocated to the French navy in these decades, the money was not well spent: the building programs reflected the frequent changes from one administration’s preference for a guerre de course (commerce-raiding) strategy to another’s firm support for battleships, leaving the navy itself with a heterogeneous collection of ships which were no match for those of the British or, later, the Germans. 88 But the impact of politics upon the French navy paled by comparison with the effect upon the army, where the strong dislike shown by the officer corps toward republican politicians and a whole host of civil-military clashes (of which the Dreyfus affair was merely the most notorious) weakened the fabric of France and placed in question both the loyalty and the efficiency of the army. Only with the remarkable post-1911 nationalist revival could these civil-military disputes be set aside in the common crusade against the German enemy; but there were many who wondered whether too heavy a dose of politics had not done irreparable damage to the French armed forces. 89

有人争辩说,法国能够贯彻这样一个有活力的殖民政策,是因为政府机构允许一小撮官僚、殖民地总督和半殖民地热心拥护者推行“前进”战略,这种战略是第三共和国变换迅速的内阁几乎没有机会加以控制的。但是,虽然法国议会政治多变的状况无意识地加强和坚定了它的帝国政策——通过把帝国政策交由常务官员及他们在殖民地问题上的“院外集团”的朋友们来掌握,但它对海军和陆军事务的影响却远不是令人愉快的。例如,政府的经常更迭使海军部长不断变换,他们之中有的人只会做官,有的人对海军战略有自己的看法,但又经常变化。在这几十年里,政府给法国海军的大量拨款没有发挥作用,这从建设计划中可以看出来。有的负责官员偏爱海上劫掠(商业掠夺)战略,有的则坚决主张建造战舰。结果留给海军的是各类舰船的大杂烩,使之无法与英国或后来的德国海军相抗衡。然而帝国政策对海军的影响与对陆军的影响相比较,就显得相形见绌了。在陆军中,军官团对共和国政治家们表现出强烈的反感,加上文官与军人之间的许多冲突(包括臭名昭著的德雷福斯事件),削弱了法国的实力,这就使人们对军队的忠诚和战斗力产生了怀疑。只是由于1911年以后出现了明显的民族振兴,文官和军人的争端才被搁置一边,以便共同对抗德国。但是仍有很多人怀疑,这种政策是否已经给法国武装部队带来难以弥补的损失。

The other obvious internal constraint upon French power was the state of its economy. 90 The position here is a complex one, and has been made the more so by economic historians’ predilections for different indices. On the positive side:

在国内,另一个明显束缚法国军事力量的因素,是它的经济状况。这里的情况也比较复杂,经济历史学家对许多不同指数的偏爱,也使它变得更加复杂化了。其中有利的因素有:

This period saw a great development in banking and financial institutions participating in industrial investment and in foreign lending. The iron and steel industry was established on modern lines and great new plants were built, especially on the Lorraine orefield. On the coalfields of northern France the familiar, ugly landscape of an industrial society took place. Important strides were made in engineering and the newer industries. … France had its notable entrepreneurs and innovators who won a leading place in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in steel, engineering, motor cars and aircraft. Firms like Schneider, Peugeot, Michelin and Renault were in the vanguard. 91

在这一时期,参加工业投资和对外信贷的银行和金融机构有了巨大的发展,并建立了现代化的钢铁工业。特别是在洛林矿区,新的工厂纷纷建成。在法国北部的产煤区,出现了工业社会通常具有的、破烂不堪的情景。在工程技术和新兴工业方面取得了重大的进展……法国有著名的企业家和革新家,19世纪末和20世纪初,他们在钢铁、工程技术、汽车和飞机制造等方面享有领先地位。施奈德、标致汽车、米其林和雷诺等公司走在时代的前列。

Until Henry Ford’s mass-production methods were developed, indeed, France was the leading automobile producer in the world. There was a further burst of railwaybuilding in the 1880s, which together with improved telegraphs, postal systems, and inland waterways, increased the trend toward a national market. Agriculture had been protected by the Meline tariff of 1892, and there remained a focus upon producing high-quality goods, with a large per capita added value. Given these indices of absolute economic expansion and the small increase in the number of Frenchmen during these decades, measurement of output which are related to France’s population look impressive—e. g. , per capita growth rates, per capita value of exports, etc.

的确,在亨利·福特大规模生产法发明之前,法国一直是世界上重要的汽车生产国。19世纪80年代,铁路建设有突飞猛进的发展,它同改进电报业、邮政和内河航运一道推动着国内市场的形成。农业受到1892年《梅里纳关税法案》的保护,同时它继续集中生产高质量的产品,人均产值大增。由于在这几十年里绝对经济增长的指数和法国人口的少量增加,产量与法国人口的对比统计是令人难忘的,例如人均增长率和出口产品的人均值等,都是如此。

Finally, there was the undeniable fact that France was immensely rich in terms of mobile capital, which could be (and systematically was) applied to serve the interests of the country’s diplomacy and strategy. The most impressive sign of this had been the very rapid paying off the German indemnity of 1871, which, in Bismarck’s erroneous calculation, was supposed to cripple France’s strength for many years to come. But in the period following, French capital was also poured out to various countries inside Europe and without. By 1914, France’s foreign investments totaled $9 billion, second only to Britain’s. While these investments had helped to industrialize considerable parts of Europe, including Spain and Italy, they had also brought large political and diplomatic benefits to France itself. The slow weaning of Italy away from the Triple Alliance at the turn of the century was attended, if not fully caused, by the Italian need for capital. Franco-Russian loans to China, in exchange for railway rights and other concessions, were nearly always raised in Paris and funneled through St. Petersburg. France’s massive investments in Turkey and the Balkans—which the frustrated Germans could never manage to match prior to 1914—gave it an edge, not only in politico-cultural terms, but also in securing contracts for French rather than German armaments. Above all, the French poured money into the modernization of their Russian ally, from the floating of the first loan on the Paris market in October 1888 to the critical 1913 offer of lending 500 million francs—-on condition that the Russian strategic railway system in the Polish provinces be greatly extended, so that the “Russian steamroller” could be mobilized the faster to crush Germany. 92 This was the clearest demonstration yet of France’s ability to use its financial muscle to bolster its own strategic power (although the irony was that the more efficient the Russian military machine became, the more the Germans had to prepare to strike quickly against France).

最后,一个不容否认的事实是:法国的流动资本极其丰富,它可以被用来(系统地用来)为国家的外交和战略服务。最令人难忘的标志是它很快便偿清了1871年对德国的赔款,这项赔款按照俾斯麦的错误估计是想使法国的力量在以后瘫痪多年。在随后的时期里,法国资本仍旧大量地涌向欧洲内外的许多国家。到1914年,法国的对外投资总额为90亿美元,仅次于英国。包括西班牙和意大利在内的欧洲大部分地区,都受到投资的帮助,实现了工业化,同时也给法国带来了大量政治和外交的利益。在进入20世纪之际,如果说意大利资金短缺并不是造成它逐渐脱离三国同盟的全部原因,那么至少它是与这些同时发生的。法国和俄国给中国贷款,在巴黎进行筹措,并通过圣彼得堡集中起来,目的在于换取筑路权和其他特权。法国在土耳其和巴尔干的投资——是受挫的德国人在19世纪以前绝对无法相比的——不仅在政治文化方面,而且在取得购买法国武器而不是德国武器的合同方面,都占了优势。最重要的是,法国人投资帮助他们的俄国同盟实现了现代化。从1888年10月在巴黎市场上第一次筹款,直到1913年提供5亿法郎的紧急贷款,条件是俄国要在波兰诸行省大大延伸其铁路网,以便把“俄国的不可抗拒的力量”迅速调过来击溃德国。这是到那时为止有效地利用它的财力支持自己战略力量的最有力的证明(虽然具有讽刺意味的是,俄国的军事机器效率越高,德国人越要加紧准备攻击法国)。

Yet once again, as soon as comparative economic data are used, this positive image of France’s growth fades away. While it was certainly a large-scale investor abroad, there is little evidence that this capital brought the country the optimal return, either in terms of interest earned93 or in a rise in foreign orders for French products: all too often, even in Russia, German merchants grabbed the lion’s share of the import trade. Germany’s proportion of exported European manufacturers had already overtaken France’s in the early 1880s; by 1911, it was almost twice as high. But this in turn reflected the awkward fact that whereas the French economy had suffered from vigorous British industrial competition a generation or two earlier, it was now being affected by the rise of the German industrial giant. With truly rare exceptions like the automobile industry, the comparative statistics time and time again measure this eclipse. By the eve of war, its total industrial potential was only about 40 percent of Germany’s, its steel production was little over one-sixth, its coal production hardly one-seventh. What coal, steel, and iron were produced was usually more expensive, coming from smaller plants and poorer mines. Similarly, for all the alleged advances of the French chemical industry, the country was massively dependent upon German imports. Given its small plants, out-of-date practices, and heavy reliance upon protected local markets, it is not surprising that France’s industrial growth in the nineteenth century had been coldly described as “arthritic … hesitant, spasmodic, and slow. ”94

然而,我们一旦引入比较经济数据,法国经济发展的真实形象便失去了光彩。虽然它无疑是一个海外投资大国,但几乎没有证据证明这些资本给国家带来了理想的报偿:无论是就所得利润而言,还是在增加外国对法国产品的订货方面都是如此。甚至在俄国,德国商人经常得到进口贸易中最大的份额。德国在欧洲出口制造商中所占的比例在19世纪80年代早期已经超过法国,到1911年几乎是法国的两倍。但是,这反过来又反映了这样一个使人难堪的事实,早在一代人或两代人之前,法国的经济就遭受着英国工业的有力竞争,而这时又受到德国工业巨人崛起的冲击。除了像汽车工业这样极少数的例外,统计数字一再表明法国经济黯然失色。到大战前夕,它的工业总潜力只相当于德国的40%左右,钢产量则刚超过德国的1/6,煤产量几乎不足德国的1/7。由于是在较小的工厂和贫穷的矿区生产,因此煤、钢和铁的成本通常比较高。同样,尽管法国化学工业已有发展,但它仍依赖从德国进口。由于工厂小,生产方法陈旧,再加上严重依赖受到保护的国内市场,19世纪法国工业的发展,被冷酷地描写成步履蹒跚、踌躇不前、时起时落、进展缓慢的过程,这是不足为奇的。

Nor were its bucolic charms any consolation, at least in terms of relative power and wealth. The blows dealt by disease to silk and wine production were never fully recovered from; and what the Meline tariff did, in its effort to protect farm incomes and preserve social stability, was to slow down the drift from the land and to support inefficient producers. With agriculture still accounting for 40 percent of the active population around 1910 and still overwhelmingly composed of smallholdings, this was an obvious drag upon both French productivity and overall wealth. Bairoch’s data show the French GNP in 1913 only 55 percent of Germany’s and its share of world manufacturing production around 40 percent of Germany’s; Wright has its national income as being $6 billion in 1914 to Germany’s $12 billion. 95 Another war with its eastern neighbor, should France stand alone, could only repeat the result of 1870–1871.

它田园生活的魅力也不能令人得到安慰,至少就相对实力和财富而言是这样。自然灾害对丝绸和酿酒业的打击从来就没有恢复过来;极力保护农业收入,维护社会稳定的《梅里纳关税法案》的实施结果,延缓了人口从农村转入城市,从而扶植了低效的生产者。1910年前后,法国有活动能力的人口中有41%从事农业,而他们绝大多数是经营小块土地,这对法国的生产力和整个国家财富显然是个累赘。贝罗克的统计资料表明,1913年法国的国民生产总值相当于德国的55%,它在世界制造业中所占的比重只相当于德国的40%左右;赖特的统计证明,1914年法国国民收入为60亿美元,而德国为120亿。如果法国同其东部邻国单独进行一次战争,只能重现1870~1871年战争的结局。