Total War and the Power Balances, 1914–1918

总体战(1914~1918)

Before examining the First World War in the light of the grand strategy of the two coalitions and of the military and industrial resources available to them, it may be useful to recall the position of each of the Great Powers within the international system of 1914. The United States was on the sidelines—even if its great commercial and financial ties to Britain and France were going to make impossible Wilson’s plea that it be “neutral in thought as in deed. ”193 Japan liberally interpreted the terms of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance to occupy the German possessions in China and in the central Pacific; neither this nor its naval-escort duties further afield would be decisive, but for the Allies it was obviously far better to have a friendly Japan than a hostile one. Italy, by contrast, chose neutrality in 1914 and in view of its military and socioeconomic fragility would have been wise to maintain that policy: if its 1915 decision to enter the war against the Central Powers was a blow to Austria-Hungary, it is difficult to say that it was the significant benefit to Britain, France, and Russia that Allied diplomats had hoped for. 194 In much the same way, it was difficult to say who benefited most from the Turkish decision to enter the war on Berlin’s side in November 1914. True, it blocked the Straits, and thus Russia’s grain exports and arms imports; but by 1915 it would have been difficult to transport Russian wheat anywhere, and there were no “spare” munitions in the west. On the other hand, Turkey’s decision opened the Near East to French and (especially) British imperial expansion—though it also distracted the imperialists in India and Whitehall from full concentration along the western front. 195

在根据两个联盟的大战略及其可以利用的经济和军事资源对第一次世界大战进行考查之前,有必要回顾一下各大国在1914年国际体系内的地位。美国处于局外人的位置——纵然它与英国和法国之间所存在的超乎寻常的商业和金融联系,使威尔逊对于美国将在“思想上和行动上保持中立”的保证成为不可能。日本为了占领德国在中国和中太平洋的属地,对英日同盟的条款做出了任意的解释;对于协约国来说,这一点及其更远方地区的海上护航任务都不具有决定性意义,但是很明显,一个友好的日本总要比一个敌对的日本好得多。相比之下,意大利在1914年选择了中立。考虑到它的军事和社会经济的脆弱性,实行这一政策应该说是明智的。即使说意大利在1915年决定参加反对同盟国的战争对奥匈帝国是一个打击,也很难说意大利的参战能像协约国的外交家们先前所希望的那样,给英国、法国和俄国带来很大好处。同样,也很难说土耳其在1914年11月决定参战,加入柏林一方到底对谁最有利。确实,土耳其封锁了海峡,从而也封锁了俄国的谷物出口和武器进口;到1915年,俄国的小麦就根本难以出口,而西方也不再有“多余的”军火可以向俄国出售。另一方面,土耳其的这一决定使近东向法国和(特别是)英国的帝国扩张敞开了大门——尽管这一决定也使在印度的帝国主义者和白厅不能把全部注意力都集中在西方战线。

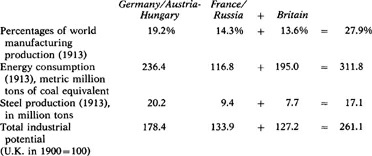

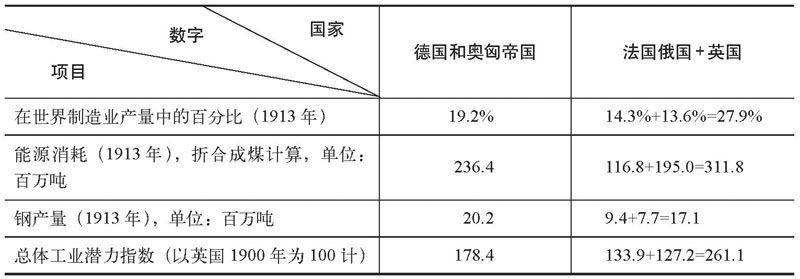

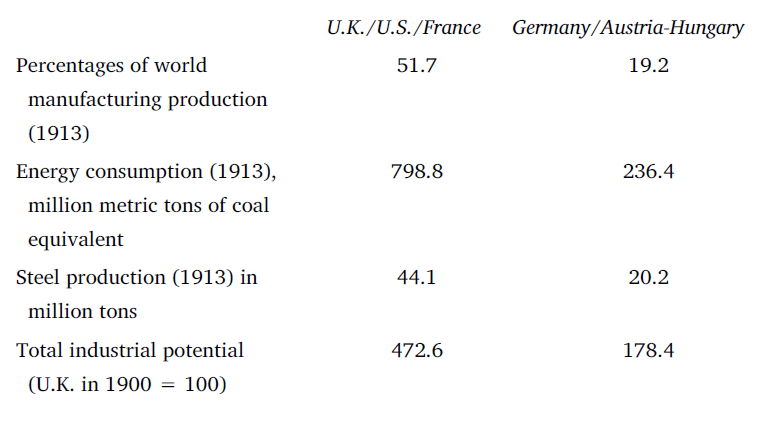

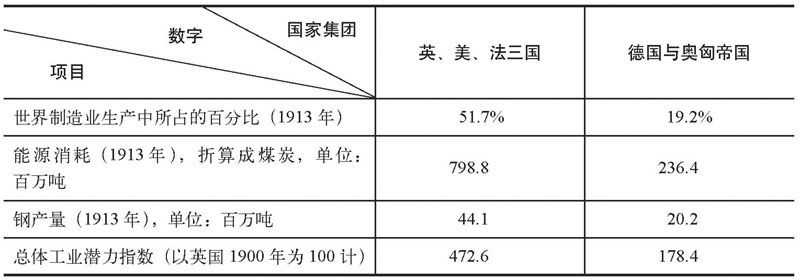

The really critical positions, therefore, were those occupied by the “Big Five” powers in Europe. By this stage, it is artificial to treat Austria-Hungary as something entirely separate from Germany, for while Vienna’s aims often diverged from Berlin’s on many issues, it could make war or peace—and probably survive as a quasi-independent Great Power—only at the behest of its powerful ally. 196 The Austro-German combination was formidable. Its front-line armies were considerably smaller than those of the French and Russian, but they operated on efficient internal lines and could be supplemented by a swelling number of recruits. As can be seen from Table 22 below, they also enjoyed a considerable superiority in industrial and technological strength over the Dual Alliance.

因此,真正具有举足轻重地位的国家是欧洲的“五大国”。到这个时候,要把奥匈帝国和德国完全区别开来对待是不可能的,因为尽管在许多问题上维也纳的目标与柏林的目标常常存在着分歧,但是维也纳只有在其强大盟国的命令之下才能够决定战争或和平问题,因此或许可以说奥匈帝国是作为一个半独立的大国存在的。奥德联盟是令人生畏的。虽然它们的前线部队要比法国和俄国的少许多,但是这些军队依靠有效的国内交通线作战,能够得到大量新兵补充。正如我们在表22中可以看到的,它们在工业和技术力量方面比起“双重联盟”来,也具有相当大的优势。

Table 22. Industrial/Technological Comparisons of the 1914 Alliances

表22 1914年两大联盟工业和技术对比表

(taken from Tables 15–18 above)

(摘自本书表15~表18)

The position of France and Russia was, of course, exactly the converse. Separated from each other by more than half of Europe, France and Russia would find it difficult (to say the least) to coordinate their military strategy. And while they appeared to enjoy a large lead in army strengths at the outset of the war, this was reduced by the clever German use of trained reservists in the front-line fighting, and this lead declined still further after the reckless Franco-Russian offensives in the autumn of 1914. With victory no longer going to the swift, it was more and more likely that it would go to the strong; and the industrial indices were not encouraging. Had the Franco-Russe alone been involved in a lengthy, “total” war against the Central Powers, it is hard to think how it could have won.

毫无疑问,法国和俄国的地位却恰恰相反。由于彼此被大半个欧洲隔开了,法国和俄国要协调它们的军事战略是困难的。尽管战争初期在军队实力方面它们看起来占了很大优势,但是这一优势由于德国人在前线作战中巧妙地使用训练有素的预备役部队而受到削弱;在1914年秋季法俄发动不计后果的攻势之后,它们的这一优势受到了进一步的削弱。胜利不再取决于速度,而是越来越可能取决于强大的实力;工业指数也并不令人鼓舞。如果由法俄两国单独与同盟国进行这场持久的“总体战”,真是很难想象它们怎么会赢得胜利。

But the fact was, of course, that the German decision to launch a preemptive strike upon France by way of Belgium gave the upper hand to British interventionists. 197 Whether it was for the traditional reasons of the “balance of power” or in defense of “poor little Belgium,” the British decision to declare war upon Germany was critical, though Britain’s small, long-service army could affect the overall military equilibrium only marginally—at least until that force had transformed itself into a mass conscript army on continental lines. But since the war was going to last longer than a few months, Britain’s strengths were considerable. Its navy could neutralize the German fleet and blockade the Central Powers—which would not bring the latter to their knees, but would deny them access to sources of supply outside continental Europe. Conversely, it ensured free access to supply sources for the Allied Powers (except when later interrupted by the U-boat campaign); and this advantage was compounded by the fact that Britain was such a wealthy trading country, with extensive links across the globe and enormous overseas investments, some of which at least could be liquidated to pay for dollar purchases. Diplomatically, these overseas ties meant that Britain’s decision to intervene influenced Japan’s action in the Far East, Italy’s declaration of neutrality (and later switch), and the generally benevolent stance of the United States. More direct overseas support was provided, naturally enough, by the self-governing dominions and by India, whose troops moved swiftly into Germany’s colonial empire and then against Turkey.

然而,毫无疑问,事实是德国决定取道比利时对法国发动一场先发制人的打击,这就使英国干涉主义者在这场竞争中取得了优势。不论是出于传统的“均势”理由,还是为了保护“可怜的小比利时”,英国决定对德宣战这一点是至关重要的,尽管英国这支小规模的实行长期兵役制的陆军只能对整个军事格局产生不大的影响——至少这支部队在欧洲大陆战线上使自己转变为一支人数众多的由征来的士兵组成的军队之前是如此。但是,由于这场战争将会持续超过几个月,英国的实力还是值得重视的。它的海军可以使德国的海军舰队瘫痪,并对同盟国实施封锁。这虽然不能迫使后者屈服,但却可阻止它们从大陆欧洲以外的地区取得资源供应。反过来说,英国海军可以保证协约国自由地取得资源供应(后来因德国发动潜艇战而中断)。而且这一优势还由于下述事实得到加强:英国是一个极为富裕的贸易国,它与全世界有着广泛的联系,它在海外拥有庞大的投资,部分海外投资至少可以用来支付用美元购买实物的开支。在外交上,这些海外联系意味着英国参战的决定还影响着日本在远东的行动,意大利宣布保持中立地位以及后来转而加入协约国一方作战的行为,以及一般说来美国乐善好施的姿态;自然还意味着各自治领和印度向英国提供更为直接的海外支援,它们的军队迅速进占了德国的殖民地,后来又用于同土耳其作战。

In addition, Britain’s still-enormous industrial and financial resources could be deployed in Europe, both in raising loans and sending munitions to France, Belgium, Russia, and Italy, and in supplying and paying for the large army to be employed by Haig on the western front. The economic indices in Table 22 show the significance of Britain’s intervention in power terms.

此外,英国仍然庞大的工业和财政金融资源还可以在欧洲发挥作用,既可用来筹措贷款,也可用来向法国、比利时、俄国和意大利运送军火,还可用来供应和支付黑格在西线使用的大军的开支。表22所列的经济指数,可以说明用实力标准来衡量英国参战的重要性。

To be sure, this made a significant rather than an overwhelming superiority in matériel possessed by the Allies, and the addition of Italy in 1915 would not weigh the scales much further in their favor. Yet if victory in a prolonged Great Power war usually went to the coalition with the largest productive base, the obvious questions arise as to why the Allies were failing to prevail even after two or three years of fighting—and by 1917 were in some danger of losing—and why they then found it vital to secure American entry into the conflict.

诚然,这一切使协约国在物质力量上占有重大的优势,但不是绝对优势,并且1915年意大利的参战也没有使天平进一步向有利于协约国的方向倾斜。可是,如果说在一场旷日持久的大国战争中,胜利通常属于拥有最大的生产基地的联盟的话,那么人们就会提出一些显而易见的问题,例如:为什么协约国甚至在战争进行了二三年以后仍然未能占上风(在1917年它们还面临过某种失败的危险)?为什么它们那时发现,促使美国参战是至关重要的?

One part of the answer must be that the areas in which the Allies were strong were unlikely to produce a swift or decisive victory over the Central Powers. The German colonial empire in 1914 was economically so insignificant that (apart from Nauru phosphates) its loss meant very little. The elimination of German overseas trade was certainly more damaging, but not to the extent that British devotees of “the influence of sea power” imagined; for the German export trades were redeployed for war production, the Central Powers bloc was virtually self-sufficient in foodstuffs provided its transport system was maintained, military conquests (e. g. , of Luxembourg ores, Rumanian wheat and oil) canceled out many raw-materials shortages, and other supplies came via neutral neighbors. The maritime blockade had an effect, but only when it was applied in conjunction with military pressures on all fronts, and even then it worked very slowly. Finally, the other traditional weapon in the British armory, peripheral operations on the lines of the Peninsular War of 1808–1814, could not be used against the German coast, since its sea-based and land-based defenses were too formidable; and when it was employed against weaker powers—at Gallipoli, for example, or Salonika—operational failures on the Allied side and newer weapons (mine fields, quick-firing shore batteries) on the defender’s side, blunted their hoped-for impact. As in the Second World War, every search for the “soft underbelly” of the enemy coalition took Allied troops away from fighting in France. 198

部分答案必定会是这样的:协约国占有优势的那些领域,不可能提供迅速或决定性战胜同盟国的条件。从经济方面来说,在1914年,德国的殖民地是无足轻重的,因此它的丧失(瑙鲁的磷酸盐除外)对德国影响很小。德国海外贸易的丧失无疑带来更大的损害,但是却不像英国的“海上力量影响”的信徒们所想象的那样严重,因为德国根据战时生产的需要重新安排了它的出口贸易,在其运输体系得以维持的情况下,同盟国集团的粮食供应事实上可以实现自给自足,军事征服(如卢森堡的矿石、罗马尼亚的小麦和石油的取得)抵消了许多原料的短缺,而其他物质的供应还可以通过中立的邻国取得。海上封锁具有某种影响,但是这种影响只有当海上封锁与所有战线上的军事压力结合起来时才可以实现,但即使在这时,它的效果也是极为缓慢地表现出来的。最后,英国武器库中的其他传统武器,像1808~1814年伊比利亚半岛战争中在各条战线上所采取的那类边缘作战行动,在这次战争中都不能用来攻击德国的海岸线,因为德国以海上和陆上为基地的防御设施太坚固。当采取这类行动对付较弱国家的军队时(如在加里波利战役或是萨洛尼卡战役中),协约国方面的作战失败和防御一方的新式武器(布雷区、速射海岸炮兵连),使它们原先希望获得的效果大打折扣。和第二次世界大战时一样,所有寻找和打击敌方联盟“柔软的下腹部”的企图,都只能使协约国军队在远离法国的地方作战。

The same points can be made about the overwhelming Allied naval superiority. The geography of the North Sea and the Mediterranean meant that the main Allied lines of communication were secure without needing to seek out their enemies’ vessels in harbor or to mount a risky close blockade of their shores. On the contrary, it was incumbent upon the German and Austro-Hungarian fleets to come out and challenge the Anglo-French-Italian navies if they wanted to gain “command of the sea”; for if they remained in port, they were useless. Yet neither of the navies of the Central Powers wished to send its battle fleets on a virtual suicide mission against vastly superior forces. Thus, the few surface naval clashes which did occur were chance encounters (e. g. , Dogger Bank, Jutland), and were strategically unimportant except insofar as they confirmed the Allied control of the seaways. The prospect of further encounters was reduced by the threat posed to warships by mines, submarines, and scouting aircraft or Zeppelins, which made the commanders of each side increasingly wary of sending out their fleets unless (a highly unlikely condition) the enemy’s ships were known to be approaching one’s own shoreline. Given this impotence in surface warfare, the Central Powers gradually turned to Uboat attacks upon Allied merchantmen, which was a much more serious threat; but by its very nature, a submarine campaign against trade was a slow, grinding affair, the real success of which could be measured only by setting the tonnage of merchant ships lost against the tonnage being launched in Allied shipyards—and that against the number of U-boats destroyed. It was not a form of war which promised swift victories. 199

关于协约国绝对的海上优势,人们也可以得出相同的看法。北海和地中海的地理位置意味着协约国的主要交通线是安全的,而不必去搜寻它们的敌人停泊于港口中的舰只,或者对敌国的海岸进行冒险的近距离封锁。相反,德国和奥匈帝国如果想要取得“制海权”的话,其海军舰队不得不主动出击,向英国、法国和意大利的海军挑战,因为舰队停留在港口内是毫无用处的。然而,同盟国的海军部不希望把它的舰队派出去对付占有巨大优势的敌国海军,执行实质上是自杀性的使命。因此,确实发生过的几次水面海战都属于偶然的遭遇战(如多格滩海战和日德兰海战),而且,这些海战除了进一步加强协约国对海上通路的控制以外,从战略上讲是没有什么重要意义的。发生进一步的海上交战的可能性由于战舰受到水雷、潜艇和齐柏林式侦察飞艇的威胁而减少,这些威胁使得双方的指挥官们越来越不想让他们的舰队出海作战,除非(这也是极不可能发生的情况)获知敌方的军舰正在接近己方的海岸线。由于海上水面交战出现这样一种软弱无力的状况,同盟国逐渐转向利用德国潜艇攻击协约国的商船,从而构成了严重得多的威胁。然而,从本质上看,打击敌方贸易的潜艇战是一种缓慢的颇费周折的事情,它的真正成功,只有通过把商船损失吨位同协约国造船厂新船下水吨位对比,以及把商船损失吨位同潜艇损失吨位进行对比之后,才能看出来。潜艇战不是一种可以保证迅速取胜的战争方式。

A second reason for the relative impotence of the Allies’ numerical and industrial superiority lay in the nature of the military struggle itself. When each side possessed millions of troops sprawling across hundreds of miles of territory, it was difficult (in western Europe, impossible) to achieve a single decisive victory in the manner of Jena or Sadowa; even a “big push,” methodically plotted and prepared for months ahead, usually disintegrated into hundreds of small-scale battlefield actions, and was usually also accompanied by a near-total breakdown in communications. While the front line might sway back and forth in certain sections, the absence of the means to achieve a real breakthrough allowed each side to mobilize and bring up reserves, fresh stocks of shells, barbed wire, and artillery in time for the next stalemated clash. Until late in the war, no army was able to discover how to get its own troops through enemy-held defenses often four miles deep, without either exposing them to withering counterfire or so churning up the ground by earlier bombardments that it was difficult to advance. Even when an occasional surprise assault overran the first few lines of enemy trenches, there was no special equipment to exploit that advantage; the railway lines were miles in the rear, the cavalry was too vulnerable (and tied to fodder supplies), heavily laden infantrymen could not move far, and the vital artillery arm was restricted by its long train of horse-drawn supply wagons. 200

协约国在军队数量和工业方面的优势没有发挥其应有作用的第二个原因,在于军事斗争本身的性质。当各方所拥有的数百万军队散乱地部署在数百英里宽的战线上时,要取得像耶拿战役或萨多瓦战役那样决定性的胜利是很困难的(在西欧,可以说是不可能的);甚至一次提前几个月有条理地计划和准备的“巨大攻势”,通常也是分成几百次小规模的战场行动,而且通常是在通信联络几乎全部中断的情形下实施的。尽管某些地段的战线可能互有进退,但由于取得一次真正突破的手段不足,使得每一方都能够及时动员和调来预备队,运来大批炮弹、有刺铁丝网和火炮等,以便进行下一次对峙战。直至战争后期,也没有哪一支军队能够找到一种方法,使己方部队突破敌方据守的纵深通常仅为4英里的防线,并且做到既不使部队暴露在敌方毁灭性的反击炮火之下,又不会为由于先前的轰击而变得难以通行的地带所阻。即使当偶尔的一次突袭攻占了敌人的前几道战壕时,部队也没有特殊的装备来利用这一有利条件扩大战果。铁路线仅在后方几英里的地方,骑兵过于易受攻击(而且还受饲料供应的限制),负载过重的步兵不能作远距离运动,而至关重要的炮兵部队却为它的由马拉补给车辆组成的长长的辎重队所限制。

In addition to this general problem of achieving a swift battlefield victory, there was the fact that Germany enjoyed two more specific advantages. The first was that by its sweeping advances in France and Belgium in August/September 1914, it had seized the ridges of high ground which overlooked the line of the western front. From that time onward, and with a rare exception like Verdun, it stayed on the defensive in the west, compelling the Anglo-French armies to attack under unfavorable conditions and with forces which, although numerically superior, were not sufficient to outweigh this basic disadvantage. Secondly, the geographical benefits of Germany’s position, with good internal means of communication between east and west, to some degree compensated for its “encirclement” by the Allies, by permitting generals such as Falkenhayn and Ludendorff to switch divisions from one front to the next, and, on one occasion, to send a whole army across central Europe in a week. 201

除了取得一次迅速的战场胜利所存在的上述基本困难外,还有这样一个事实:德国方面拥有两个特定的有利条件。第一个有利条件是,德国军队1914年8月和9月间在法国和比利时的快速推进,使它夺取了高地的山脊线,因而能从那里俯瞰整个西方战线。从那时起,除了像凡尔登战役这样极少数例外场合,德国军队在西线一直处于守势,迫使英法联军不得不在极为不利的条件下发动进攻,其进攻部队尽管在人数上占优势,但仍不足以克服这一基本的不利条件。第二个有利条件是德国优越的地理位置,其东西方之间有着良好的国内交通设施,这在一定程度上抵消了协约国对它的“包围”,也使得法金汉[12]和鲁登道夫[13]等将军们能够把军队从一条战线调到另一条战线,而且有一次竟在一周之内指挥整整一个集团军横跨中欧机动作战。

Consequently, in 1914, even as the bulk of the army was attacking in the west, the Prussian General Staff was nervously redeploying two corps to reinforce its exposed eastern front. This action was not a fatal blow to the westward strike, which was logistically unsound in any case;202 and it did help the Germans to counter the premature Russian offensive into East Prussia by launching their own operation around the Masurian Lakes. When the bloody fighting at Ypres in November 1914 convinced Falkenhayn of the hopelessness of achieving a swift victory in the west, a further eight German divisions were transferred to the eastern command. Since the Austro-Hungarian forces had suffered a humiliating blow in their Serbian campaign, and since the unreal French Plan XVII of 1914 had ground to a halt in Lorraine with losses of over 600,000 men, it appeared that only in the open lands of Russian Poland and Galicia could a breakthrough be effected— although whether that would be a Russian repeat of their victory over Austria- Hungary at Lemberg or a German repeat of Tannenberg/Masurian Lakes was not at all clear. As the Anglo-French armies were battering away in the west throughout 1915 (where the French lost a further 1. 5 million men and the British 300,000), the Germans prepared for a series of ambitious strikes along the eastern front, partly to rescue the beleaguered Austro-Hungarians in Carpathia, but chiefly to destroy the Russian army in the field. In fact, the latter was still so large (and growing) that its destruction was impossible; but by the end of 1915 the Russians had suffered a series of devastating blows at the hands of the tactically and logistically superior Germans, and had been driven from Lithuania, Poland, and Galicia. In the south, German reinforcements had joined the Austrian forces, and the opportunistic Bulgarians, in finally overrunning Serbia. Nothing that the western Allies attempted in 1915—from the operationally mishandled Gallipoli campaign, to the fruitless landing at Salonika, to inducing Italy into the war—really aided the Russians or seemed to challenge the consolidated bloc of the Central Powers. 203

因此,在1914年,甚至当陆军主力正在西线发动进攻时,普鲁士总参谋部就神经质地抽调两个军增援其暴露的东线。这一行动并没有对西方战线的攻势产生重大影响(从后勤支援方面说,这一攻势是绝对不恰当的),但确实有助于德军反击俄军过早发动的入侵东普鲁士的攻势(俄军是在马祖里湖附近开始其进攻的)。1914年11月,在伊普雷进行的残酷战斗使法金汉相信,在西方取得迅速的胜利已毫无希望,于是他又将8个德国师调往东战场。由于奥匈帝国的军队在塞尔维亚战局中遭到了屈辱性的打击,又由于法军于1914年实施不切实际的第17号作战计划时,损失了60万人之后受阻于洛林,看起来只有在俄属波兰和加利西亚的开阔地带进行一次突破才可能收到效果,尽管对于俄军是否会重演它在伦贝格作战中对奥匈帝国军队的胜利,或者德军是否会重演它在坦能堡和马祖里湖作战中的胜利,还一点也没有把握。当1915年全年英法联军在西方战线发动了连续不断的强大攻势(法军又损失了150万人,英军损失了30万人)时,德国人则准备沿东线发动一系列野心勃勃的突击,实施这些突击的部分原因是为了营救在喀尔巴阡山地区被围困的奥匈帝国军队,但主要还是为了歼灭战场上的俄国军队。事实上,俄国军队仍然十分庞大(而且还在不断增加兵力),要歼灭它是不可能的。但是,到了1915年底,俄军遭到了在战术上和后勤供应上都占优势的德军的一系列毁灭性打击,并被赶出了立陶宛、波兰和加利西亚。在南方,德军的援军和奥地利军队以及机会主义的保加利亚军协同作战,最后终于征服了塞尔维亚。在1915年,西方协约国的所有努力,无论是指挥无方的加利波利战役和毫无结果的萨洛尼卡登陆战役,还是劝意大利参战,都没能对俄国人真正有所帮助,或者是在表面上对同盟国牢固的集团构成严重挑战。

In 1916, Falkenhayn’s unwise reversal of German strategy—shifting units westward in order to bleed the French to death by the repeated assaults upon Verdun—merely confirmed the correctness of the older policy. While large numbers of German divisions were being ruined by the Verdun campaign, the Russians were able to mount their last great offensive under General Brusilov in the east, in June 1916, driving the disorganized Habsburg army all the way back to the Carpathian mountains and threatening its collapse. At almost the same time, the British army under Haig launched its massive offensive at the Somme, pressing for months against the well-held German ridges. As soon as these twin Allied operations had led to the winding-down of the Verdun campaign (and the replacement of Falkenhayn by Hindenburg and Ludendorff in late August 1916), the German strategical position improved. German losses on the Somme were heavy, but were less than Haig’s; and the switch to a defensive stance in the West once again permitted the Germans to transfer troops to the east, stiffening the Austro-Hungarian forces, then overrunning Rumania, and later giving aid to the Bulgarians in the south. 204

1916年,法金汉为了彻底制服法国而移师西线,向凡尔登发动了连续的攻击。德国在战略上的这一不明智的改变,只是进一步证明了它先前政策的正确性。当大量的德国师在凡尔登战役中正在覆灭时,俄国人却能够在东线于1916年6月在勃鲁西洛夫将军的指挥下发动最后的大规模攻势,把已瓦解的奥匈帝国军队一路赶回到喀尔巴阡山地区,从而使它面临崩溃的危险。差不多与此同时,在黑格的指挥下,英国军队在索姆河一线发动了大规模攻势,一连几个月对德军有效防守的山脊线施加了强大的压力。协约国军队的这两次同时进行的作战行动,导致了凡尔登战役中的拉锯战(法金汉在1916年8月底被兴登堡和鲁登道夫所取代),德国的战略地位从而改善了。德军在索姆河战役中的损失是很大的,但比黑格的损失还是轻些;西线转入防御态势又一次使德国人能够移师东线,促使奥匈帝国军队坚挺起来,然后占领罗马尼亚,并援助了南方的保加利亚军。

Apart from these German advantages of inner lines, efficient railways, and good defensive positions, there was also the related question of timing. The larger total resources which the Allies possessed could not be instantly mobilized in 1914 in the pursuit of victory. The Russian army administration could always draft fresh waves of recruits to make up for the repeated battlefield losses, but it had neither the weapons nor the staff to expand that force beyond a certain limit. In the west, it was not until 1916 that Haig’s army totaled more than a million men, and even then the British were tempted to divert their troops into extra-European campaigns, thus reducing the potential pressure upon Germany. This meant that during the first two years of the conflict, Russia and France took the main burden of checking the German military machine. Each had fought magnificently, but by the beginning of 1917 the strain was clearly showing; Verdun had taken the French army close to its limits, as Nivelle’s rash assaults in 1917 revealed; and although the Brusilov offensive had virtually ruined the Habsburg army as a fighting force, it had done no damage to Germany itself and had placed even more strains upon Russian railways, food stocks, and state finances as well as expending much of the existing trained Russian manpower. While Haig’s new armies made up for the increasing weariness of the French, they did not portend an Allied victory in the west; and if they also were squandered in frontal offensives, Germany might still be able to hold its own in Flanders while indulging in further sweeping actions in the east. Finally, no help could be expected south of the Alps, where the Italians were now desperately calling for assistance.

德军方面除了拥有处于内线、有着有效的铁路网和良好的防御阵地这些有利条件之外,还在与之有关的时间选择方面处于有利地位。协约国拥有较多的资源,但在1914年未能迅速动员起来以争取胜利。俄军后方机构总是能征募一批又一批的新兵来补充连续不断的战场损失,但是既没有武器也没有参谋机构来进一步加强这支军队使其发挥最大限度的作用。在西线,黑格的军队直到1916年总人数才达到100余万人,而在那时英国人还是想把他们的军队转到欧洲以外的战场上,而这样做自然会减轻对德军的潜在压力。这意味着在战争的头两年里,俄国和法国担负着扼制德国军事机器的主要任务。每一方都进行了极为壮观的交战,但是到1917年初,双方兵力的衰竭就已清楚地显现出来了。凡尔登战役使法国的军队实力接近于它的极限,1917年尼韦勒发动的孤注一掷的进攻就说明了这一点。虽然勃鲁西洛夫的进攻实际上已经摧毁了奥匈帝国军队,使其不再成为一支战斗部队,但却没有对德军本身造成任何损害,反而使俄国铁路运输线、粮食贮备和国家财政更加极度紧张,并使现有的训练有素的俄军兵力遭受了大量损失。虽然黑格新增加的部队弥补了法军的日益衰弱,但是并不预示着协约国会在西线取得胜利,而且如果这些部队也被滥用于正面进攻中,德军可能仍能在弗兰德斯固守自己的阵地,与此同时,在东线进一步采取大规模攻势行动。最后,不能指望从阿尔卑斯山脉南面得到什么帮助,在那里,意大利人正在绝望地乞求支援。

This pattern of ever-larger military sacrifices made by each side was paralleled, inevitably, in the financial-industrial sphere—but (at least until 1917) with the same stalemated results. Much has been made in recent studies of the way in which the First World War galvanized national economies, bringing modern industries for the first time to many regions and leading to stupendous increases in armaments output. 205 Yet on reflection, this surely is not surprising. For all the laments of liberals and others about the costs of the pre-1914 arms race, only a very small proportion (slightly over 4 percent on average) of national income was being devoted to armaments. When the advent of “total war” caused that figure to rise to 25 or 33 percent—that is, when governments at war took decisive command of industry, labor, and finance—it was inevitable that the output of armaments would soar. And since the generals of every army were bitterly complaining by late 1914 and early 1915 of a chronic “shell shortage,” it was also inevitable that politicians, fearing the effects of being found wanting, entered into an alliance with business and labor to produce the desired goods. 206 Given the powers of the modern bureaucratic state to float loans and raise taxes, there were no longer the fiscal impediments to sustaining a lengthy war that had crippled eighteenth-century states. Inevitably, then, after an early period of readjustment to these new conditions, armaments production soared in all countries.

这种双方都在不断付出大规模军事牺牲的情况,在财政与工业领域里也不可避免地同时存在,而且(至少在1917年以前)产生了同样的相持不下的结果。在最近的研究中,人们就第一次世界大战中刺激国家经济发展的方式进行了深入探讨,那时的经济发展方式第一次把现代工业扩大到了许多领域,并导致军工生产的大幅度增加。然而,只要认真反思一下,我们就会发现这一点毫不令人惊奇。自由主义者和其他人曾对1914年以前军备竞赛的开支发出过一片惋惜声,可是用于军备的开支只占国家收入很小一部分(平均为4%多一点)。当“总体战”的到来使这一数字增加到25%或33%时,也就是说,当战时政府决定性地控制了国家的工业、劳动力和财政时,军工产品的增长是不可避免的。而且,由于1914年末和1915年初各方军队的将军们都在苦苦地抱怨经常发生的“炮弹短缺”,害怕这种短缺被发现而产生不良后果的政治家们,也必然要与实业界和劳工联合起来,去生产所需要的军用物资。由于现代官僚国家具有发行公债和提高税收的权力,曾使18世纪国家在维持一场长期战争中遇到的那些使其步履艰难的财政障碍已不复存在。因此,所有国家在早期就为适应这些新情况而作了调整之后,其军工生产都迅速猛增。

It is therefore important to ask where the wartime economies of the various combatants showed weaknesses, since it was most likely that this would lead to collapse, unless aid came from better-endowed allies. In this respect, little space will be given to the two weakest of the Great Powers, Austria-Hungary and Italy, since it is clear that the former, although holding up remarkably well in its extended campaigning (especially on the Italian front), would have collapsed in its war with Russia had it not been for repeated German military interventions which turned the Habsburg Empire ever more into a satellite of Berlin;207 while Italy, which did not need anywhere like that degree of direct military assistance until the Caporetto disaster, was increasingly dependent upon its richer and more powerful allies for vital supplies of foodstuffs, coal, and raw materials, for shipping, and for the $2. 96 billion of loans with which it could pay for munitions and other produce. 208 Its eventual “victory” in 1918, like the eventual defeat and dissolution of the Habsburg Empire, essentially depended upon actions and decisions taken elsewhere.

所以,研究一下各参战国的战时经济在哪些方面存在着弱点是十分重要的,因为要是得不到来自情况良好的盟国的支援,这些弱点最有可能导致它们崩溃。在这方面,我们不打算对大国中最软弱的两个国家——奥匈帝国和意大利——进行详细的分析,因为很清楚,前者尽管很出色地守住了它漫长的战线(特别是意大利战线),但如果没有德国不断的军事增援(这一增援使奥匈帝国更进一步成为柏林的卫星国),它早就在与俄国的战争中崩溃了。至于意大利(在卡波雷托惨败之前,它是不需要那种程度的直接军事援助的),则日益严重地依赖其更为富裕和强大的盟国向它提供必不可少的粮食、煤、原料、海运工具,及29.6亿美元的贷款以购买军火和其他军用品。同奥匈帝国的最后失败和解体一样,意大利1918年的最后“胜利”主要取决于其他地区采取的行动和决策。

By 1917, it has been argued,209 Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Russia were racing each other to collapse. That Russia should actually be the first to go was due, in large part, to two problems from which Rome and Vienna were spared; the first was that it was exposed, along hundreds of miles of border, to the slashing attacks of the much more efficient German army; the second was that even in August 1914 and certainly after Turkey’s entry into the war, it was strategically isolated and thus never able to secure the degree of either military or economic aid from its allies necessary to sustain the enormous efforts of its fighting machine. When Russia, like the other combatants, swiftly learned that it was using up its ammunition stocks about ten times faster than the prewar estimates, it had massively to expand its home production—which turned out to be far more reliable than waiting for the greatly delayed overseas orders, even if it also implied diverting resources into the self-interested hands of the Moscow industrialists. But the impressive rise in Russian arms output, and indeed in overall industrial and agricultural production, during the first two and a half years of the war greatly strained the inadequate transport system, which in any case was finding it hard to cope with the shipment of troops, fodder for the cavalry, and so on. Shell stocks therefore accumulated miles from the front; foodstuffs could not be transported to the deficit areas, especially in the cities; Allied supplies lay for months on the harborsides at Murmansk and Archangel. These infrastructural inadequacies could not be overcome by Russia’s minuscule and inefficient bureaucracy, and little help came from the squabbling and paralyzed political leadership at the top. On the contrary, the czarist regime helped to dig its own grave by its recklessly unbalanced fiscal policies; having abolished the trade in spirits (which produced one-third of its revenue), losing heavily on the railways (its other great peacetime source of income), and—unlike Lloyd George—declining to raise the income tax upon the better-off classes, the state resorted to floating ever more loans and printing ever more paper in order to pay for the war. The price index spiraled, from a nominal 100 in June 1914 to 398 in December 1916, to 702 in June 1917, by which time an awful combination of inadequate food supplies and excessive inflation triggered off strike after strike. 210

人们争论说,到了1917年,意大利、奥匈帝国和俄国彼此都在竞相走向崩溃。事实上,俄国应该首先走向崩溃,其原因在很大程度上要归于罗马和维也纳都不存在的两个问题:其一,它的几百英里长的国境线暴露在战斗力强大得多的德国军队的猛烈打击之下;其二,甚至在1914年8月,当然也包括土耳其参战以后,俄国在战略上一直处于孤立无援的地位,它从未能从其盟国那里得到必要的军事或经济援助,以维持其庞大的战争机器的运转。与其他参战国一样,当俄国很快意识到它的弹药贮备消耗速度要比战前估计的快10倍时,俄国便大规模增加其国内军工生产,结果证明,这样做要比等待已被大大推迟的海外军事订货可靠得多,即使这样做意味着它的资源要转移到自私自利的莫斯科工业家手中也在所不惜。在战争开始的头两年半时间里,俄国的武器生产,甚至是全部工业和农业生产,都取得了引人注目的增长,然而这一增长却受到了不良的交通系统的严重限制;它的运输系统在任何情况下都难以应付调动军队、为骑兵运送饲料以及其他方面的需要。因此,它的炮弹常常大量堆积在距离前线几英里以外的地方,粮食也无法及时运送到缺粮地区,特别是城市地区;协约国送来的补给物资在摩尔曼斯克和阿尔汉格尔斯克的港口一放就是几个月。俄国的这种缺少活力和工作效率不高的官僚机构,是无法克服这些组织上的缺陷的,而来自上层那些好争吵、处于瘫痪状态的政治领导的帮助则微乎其微。相反,由于采取不计后果的和失去平衡的财政政策,沙皇政权实际上是在自掘坟墓。沙皇政府的财政政策实质上禁止了贸易活动(贸易可为其提供l/3的收入),铁路运输收入损失严重(和平时期另一重要收入来源);而且,与劳埃德·乔治[14]相反,沙皇拒绝提高较富裕阶层的收入所得税,国家求助于发行更多的公债和印制更多的纸币,来支付战争费用。俄国的价格指数螺旋式地上升,如1914年6月为100,而到1916年12月初就增至398,1917年6月又进一步增至702;到1917年6月,粮食供应的不足和极度的通货膨胀可怕地相结合,激发了一次又一次的罢工浪潮。

As in industrial production, Russia’s military performance was creditable during the first two or three years of the war—even if it was nothing like those fatuous prewar images of the “Russian steamroller” grinding its way across Europe. Its troops fought in their usual dogged, tough manner, enduring hardships and discipline unknown in the west; and the Russian record against the Austro- Hungarian army, from the September 1914 victory at Lemberg to the brilliantly executed Brusilov offensive, was one of constant success, akin to its Caucasus campaign against the Turks. Against the better-equipped and faster-moving Germans, however, the record was quite the reverse; but even that needs to be put into perspective, since the losses of one campaign (say, Tannenberg/Masurian Lakes in 1914, or the Carpathian fighting in 1915) were made up by drafting a fresh annual intake of recruits, which were then readied for the next season’s operations. Over time, of course, the quality and morale of the army was bound to be affected by these heavy losses—250,000 at Tannenberg/Masurian Lakes, 1 million in the early 1915 Carpathian battles, another 400,000 when Mackensen struck at the central Polish salient, as many as 1 million in the 1916 fighting which started with the Brusilov offensive and ended with the debacle in Rumania. By the end of 1916, the Russian army had suffered casualties of some 3. 6 million dead, seriously sick, and wounded, and another 2. 1 million had been captured by the Central Powers. By that time, too, it had decided to call up the second-category recruits (males who were the sole breadwinners in the family), which not only produced tremendous peasant unrest in the villages, but also brought into the army hundreds of thousands of bitterly discontented conscripts. Almost as important were the dwindling numbers of trained NCOs, the inadequate supplies of weapons, ammunition, and food at the front, and the growing sense of inferiority against the German war machine, which seemed to know in advance all of Russia’s intentions,* to have overwhelming artillery fire, and to move faster than anyone else. By the beginning of 1917 these repeated defeats in the field interacted with the unrest in the cities and the rumors of the distribution of land, to produce a widespread disintegration in the army. Kerensky’s July 1917 offensive—once again, initially successful against the Austrians, and then slashed to pieces by Mackensen’s counterattack—was the final blow. The army, Stavka concluded, “is simply a huge, weary, shabby, and illfed mob of angry men united by their common thirst for peace and by common disappointment. ”211 All that Russia could look forward to now was defeat and an internal revolution far more serious than that of 1905.

和工业生产一样,在战争开始后头两三年的时间里,俄国的军事成就也是值得赞扬的,尽管这时俄国的形象一点也不像战前想象的“俄国蒸汽压路机”碾过整个欧洲的那种笨拙形象。俄国军队以它固有的执着而顽强的方式进行着战斗,忍受着西方人所想象不到的艰苦和纪律约束。俄国同奥匈帝国军队作战的战绩——从1914年9月在伦贝格的胜利,到出色的勃鲁西洛夫攻势作战——只是一系列胜利中的几次,在同土耳其人进行的高加索战局中也取得了类似的战绩。然而,俄国同装备精良、机动性强的德军作战时,其战绩则完全相反。但是,对其同德军作战的表现也要全面地看待,因为一次战役(如1914年的坦能堡和马祖里湖战役或1915年的喀尔巴阡战役)的损失,可以通过每一年度征集的新兵得到弥补,这样就为下一季节的战役行动做好了准备。当然,在一段时间内,军队的素质和士气肯定会受到下述惨重损失的影响:俄军在坦能堡和马祖里湖战役中损失了25万人,在1915年初期的喀尔巴阡战役中损失了100万人,在抗击马肯森对波兰中央突出部发动的进攻中损失了40万人,从勃鲁西洛夫发动攻势起到罗马尼亚崩溃为止的1916年交战中又损失了100万人;这样,到1916年年底为止,俄国军队共死伤360万人,另外还有210万人被同盟国军队俘虏。也正是从那时开始,俄国决定征召第二类新兵(即家庭中唯一养家糊口的男性)入伍,这不仅引起了乡村中农民的巨大不安,而且还使成千上万怀有严重不满情绪的新兵进入了军队。几乎同样重要的还有:训练有素的士官人数日益减少,前线武器、弹药和粮食供给不足,以及面对德国战争机器日益增强的自卑感——德国战争机器似乎事先知道俄国人的所有意图[15],它拥有占压倒优势的炮火,比任何人的行动都要迅速。到1917年初,战场上连续不断的失败、城市中的骚动以及分配土地的谣言等事件的综合影响,便引起了军队的普遍瓦解。克伦斯基于1917年7月发动的攻势是最后的一次打击。和先前的攻势作战一样,这次攻势在初期对奥地利军队实施了成功的打击,后来却被马肯森的反击打得七零八落。对于这支军队,俄军最高统帅部作了这样的概括:它“简直就是由共同的渴望和平和共同的失望联合起来的愤怒的人们组成的一群庞大的、疲惫不堪的、衣衫褴褛和营养不良的乌合之众”。现在,俄国所期待的只能是失败和一次比1905年革命更为严重的国内革命。

It is idle to speculate how close France, too, came to a similar fate by mid-1917, when hundreds of thousands of soldiers mutinied following Nivelle’s senseless offensive;212 for the fact was that despite the superficial similarities with Russian conditions, the French possessed key advantages which kept them in the fight. The first was the far greater degree of national unity and commitment to drive the German invaders back to the Rhine—although even those feelings might have faded away had France been fighting on its own. The second, and probably crucial, difference was that the French could benefit from fighting a coalition war in the way that Russia could not. Since 1871, they had known that they could not stand alone against Germany; the 1914–1918 conflict simply confirmed that judgment. This is not to downgrade the French contribution to the war, either in military or economic items, but merely to put it in context. Given that 64 percent of the nation’s pig-iron capacity, 24 percent of its steel capacity, and 40 percent of its coal capacity fell swiftly into German hands, the French industrial renaissance after 1914 was remarkable (suggesting, incidentally, what could have been done in the nineteenth century had the political commitment been there). Factories, large and small, were set up across France, and employed women, children, and veterans, and even conscripted skilled workers who were transferred back from the trenches. Technocratic planners, businessmen, and unions combined in a national effort to produce as many shells, heavy guns, aircraft, trucks, and tanks as possible. The resultant surge in output has caused one scholar to argue that “France, more than Britain and far more than America, became the arsenal of democracy in World War I. ”213

我们不再赘述1917年年中的法国也多么近似于这种命运,在尼韦勒发动毫无意义的攻势之后,成千上万的士兵哗变。事实上,尽管法国所处的条件与俄国的条件有着表面上的相似之处,但法国却拥有使它在战争中得以维持下去的关键性的有利条件。第一个有利条件是,程度高得多的国家团结一致性和把德国侵略者赶回莱茵河的义务感,当然,如果这场战争是法国主动挑起的,它的这些情感可能会消失。第二个也可能是至关重要的条件是,法国能够从一场联盟战争中获益,而俄国却不能。自1871年以来,法国人就已经懂得他们不能单独地同德国对抗,1914~1918年的战争只是进一步证实了这一判断。这并不是从军事上或经济上贬低法国对这场战争的贡献,而仅仅是为了把法国放在具体背景下来作分析。考虑到法国64%的生铁生产能力、24%的钢生产能力和40%的煤炭生产能力迅速地落入德国手中,可以说法国1914年以后的工业复兴还是很显著的(顺便说一下,这也说明如果具有政治义务感的话,法国在19世纪能够干出多么辉煌的业绩来)。大大小小的工厂在法国各地建立起来,雇用了妇女、儿童和退伍军人,甚至还包括那些被从战壕调回来的应征入伍的熟练工人从事生产。技术专家治国论的设计者、实业家和工会联合起来,举国一致地努力生产尽可能多的炮弹、重型火炮、飞机、卡车和坦克。法国最终取得的军工生产量的剧增竟使一位学者断言道:“不是英国,更不是美国,而是法国在第一次世界大战中成了民主国家的兵工厂。”

Yet this top-heavy concentration upon armaments output—increasing machinegun production 170-fold, and rifle production 290-fold—could never have been achieved had France not been able to rely upon British and American aid, which came in the form of a steady flow of imported coal, coke, pig iron, steel, and machine tools so vital for the new munitions industry; in the Anglo-American loans of over $3. 6 billion, so that France could pay for raw materials from overseas; in the allocation of increasing amounts of British shipping, without which most of this movement of goods could not have been carried out; and in the supply of foodstuffs. This last-named category seems a curious defect in a country which in peacetime always produced an agricultural surplus; but the fact was that the French, like the other European belligerents (except Britain), hurt their own agriculture by taking too many men from the land, diverting horses to the cavalry or to army-transport duties, and investing in explosives and artillery to the detriment of fertilizer and farm machinery. In 1917, a bad harvest year, food was scarce, prices were spiraling ominously upward, and the French army’s own stock of grain was reduced to a twoday supply—a potentially revolutionary situation (especially following the mutinies), which was only averted by the emergency allocation of British ships to bring in American grain. 214

然而,如果法国没有来自英国和美国的援助,它也不可能把大量的投资集中于武器生产——机枪产量增加到170倍,步枪产量增加到290倍。这些援助包括:不断地向法国输送新军火工业必需的煤、焦炭、生铁、钢和机床;英美向法国提供了总数超过36亿美元的贷款,从而使法国能够支付购买海外原料的费用;英国的运输能力分配给法国使用的那部分日益增加,没有这一援助,法国的大多数商品便无法流通;法国还可以得到盟国的粮食供应。最后提到的这项援助对于法国来说似乎是难以令人理解的,因为平时法国的农业生产一直是自给有余。然而事实是,和欧洲其他参战国(英国除外)一样,法国由于把过多的人力从土地上抽走,把马匹转交给骑兵使用或者用来执行军队运输任务,以及因投资制造炸药和生产大炮而减少肥料和农业机械生产,致使整个农业生产受到了损害。1917年是一个歉收年,粮食短缺,价格不断地螺旋式上涨,法军本身的粮食贮备减少到只够两天的供应——从而引起了一种潜在的革命危机(特别是在刚刚发生过士兵哗变之后),这种形势通过紧急调拨英国商船把美国的粮食运来才防止了。

In rather the same way, France needed to rely upon increasing amounts of British and, later, American military assistance along the western front. For the first two to three years of the war, it bore the brunt of that fighting and took appalling casualties—over 3 million even before Nivelle’s offensive of 1917; and since it had not the vast reserves of untrained manpower which Germany, Russia, and the British Empire possessed, it was far harder to replace such losses. By 1916–1917, however, Haig’s army on the western front had been expanded to two-thirds the size of the French army and was holding over eighty miles of the line; and although the British high command was keen to go on the offensive in any case, there is no doubt that the Somme campaign helped to ease the pressure upon Verdun—just as Passchendaele in 1917 took the German energies away from the French part of the front while Pétain was desperately attempting to rebuild his forces’ morale after the mutinies, and waiting for the new trucks, aircraft, and heavy artillery to do the work which massed infantry clearly could not. Finally, in the epic to-and-fro battles along the western front between March and August 1918, France could rely not only upon British and imperial divisions, but also upon increasing numbers of American ones. And when Foch orchestrated his final counteroffensive in September 1918, he could engage the 197 under-strength German divisions with 102 French, 60 British Empire, 42 (double-sized) American, and 12 Belgian divisions. 215 Only with a combination of armies could the formidable Germans at last be driven from French soil and the country be free again.

同样,在整个西方战线,法国需要日益依赖英国和后来的美国军事援助。在战争的头两三年里,法国在战场上首当其冲,付出了令人震惊的伤亡,甚至在尼韦勒发动1917年攻势之前,伤亡人数就已超过了300万。而且由于法国没有德国、俄国和大英帝国所拥有的未经训练的庞大人力后备,法国要想补充这些损失也困难得多。然而,到1916~1917年,西方战线上黑格的军队便已增加到相当于法军总兵力的2/3,并据守着80多英里长的战线。英国最高统帅部热衷于不顾一切地发动攻势。毫无疑问,索姆河战役确实有助于减轻德军对凡尔登的压力——这正像1917年帕森达勒战役中发生的情况一样,那次战役吸引了德军对法军防守战线的注意力,而当时贝当在士兵哗变事件发生后正在竭力试图重振他的军队的士气,等待新的卡车、飞机和重型火炮来完成靠密集的步兵显然不能完成的任务。最后,在1918年3月到9月沿西线进行的大规模拉锯战中,法军不仅可以依靠英国及其帝国的师,还能够依靠日益增多的美国师进行作战。而且,当福煦[16]在1918年9月组织最后的反攻时,可供他使用的兵力有102个法国师、60个英帝国师、42个美国师(其规模要比其他国家的师大一倍)和12个比利时师,而与之相对抗的德军仅有197个不满员的师。只有这些国家的军队联合行动,才能够最后把令人生畏的德军赶出法国领土,使这个国家再次获得自由。

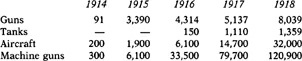

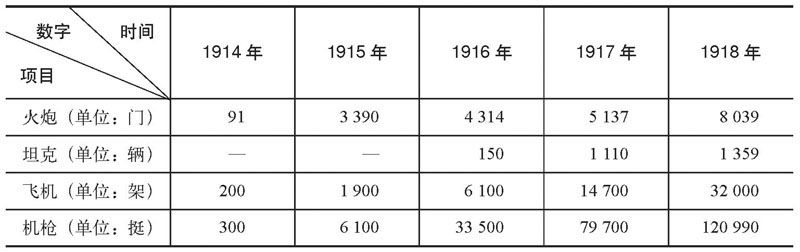

When the British entered the war in August 1914, it was with no sense that they, too, would become dependent upon another Great Power in order to secure ultimate victory. So far as can be deduced from their prewar plans and preparations, the strategists had imagined that while the Royal Navy was sweeping German merchantmen (and perhaps the High Seas Fleet) from the oceans, and while the German colonial empire was being seized by dominion and British Indian troops, a small but vital expeditionary force would be sent across the Channel to “plug” a gap between the French and Belgian armies and to hold the German offensive until such time as the Russian steamroller and the French Plan XVII were driving deep into the Fatherland. The British, like all the other powers, were not prepared for a long war, although they had taken certain measures to avoid a sudden crisis in their delicate international credit and commercial networks. But unlike the others, they were also not prepared for large-scale operations on the continent of Europe. 216 It was therefore scarcely surprising that one to two years of intense preparation were needed before 1 million British troops stood ready in France, and that the explosion of government spending upon rifles, artillery, machine guns, aircraft, trucks, and ammunition merely revealed innumerable production deficiencies which were only slowly corrected by Lloyd George’s Ministry of Munitions. 217 Here again there were fantastic rises in output, as shown in Table 23.

当1914年8月英国参战时,英国没有意识到,为了取得最后胜利它也要依赖另一个大国。这可以从它的战前计划和准备方面推断出来。英国的战略家们设想:在皇家海军从海上扫荡德国的商船队(可能还有公海舰队)、自治领和英印军队夺取德国的殖民地的同时,有必要派出一支小规模的、必不可少的远征军跨过海峡去“堵塞”法比军队之间的缺口,顶住德国的攻势,直到俄国的“蒸汽压路机”和法国按照第17号作战计划指挥的大军长驱直入德国本土。和所有其他国家一样,英国也没有做好进行长期战争的准备,尽管它曾采取过一些措施来防止其脆弱的国际信贷和商业网突然陷入危机。但是,与其他国家不同,英国也没有为在欧洲大陆进行大规模的军事行动做好准备。因此,人们对下面的情况就不感到奇怪了:英国进行一两年紧张的准备工作之后,才使100万军队开进法国;政府为大量生产步枪、火炮、机枪、飞机、卡车和弹药而使开支剧增,暴露出生产方面存在着许多缺点,这些问题只能由劳埃德·乔治的军需部慢慢地解决。在这里,我们又一次看到军工生产难以置信的大规模增长,参看表23。

Table 23. U. K. Munitions Production, 1914–1918218

表23 英国军火产量一览表(1914~1918年)

But that is scarcely surprising when one realizes that British defense expenditures rose from £91 million in 1913 to £1. 956 billion in 1918, by which time it represented 80 percent of total government expenditures and 52 percent of the GNP. 219

但是,当人们想到英国的防务开支从1913年的9100万英镑,增加到1918年的19.56亿英镑时,就丝毫不会对其军火产量的猛增感到惊讶了。到1918年,英国的防务开支占政府总开支的80%,占国民生产总值的52%。

To give full details of the vast growth in the number of British and imperial divisions, squadrons of aircraft, and batteries of heavy artillery seems less important, therefore, than to point to the weaknesses which the First World War exposed in Britain’s overall strategical position. The first was that while geography and the Grand Fleet’s numerical superiority meant the Allies retained command of the sea in the surface conflict, the Royal Navy was quite unprepared to counter the unrestricted U-boat warfare which the Germans were implementing by early 1917. The second was that whereas the cluster of relatively cheap strategical weapons (blockade, colonial campaigns, amphibious operations) did not seem to be working against a foe with the wide-ranging resources of the Central Powers, the alternative strategy of direct military encounters with the German army also seemed incapable of producing results—and was fearfully costly in manpower. By the time the Somme campaign whimpered to a close in November 1916, British casualties in that fighting had risen to over 400,000. Although this wiped out the finest of Britain’s volunteers and shocked the politicians, it did not dampen Haig’s confidence in ultimate victory. By the middle of 1917 he was preparing for yet a further offensive from Ypres northeastward to Passchendaele—a muddy nightmare which cost another 300,000 casualties and badly hurt morale throughout much of the army in France. It was, therefore, all too predictable that however much Generals Haig and Robertson protested, Lloyd George and the imperialist-minded War Cabinet were tempted to divert ever more British divisions to the Near East, where substantial territorial gains beckoned and losses were far fewer than would be incurred in storming well-held German trenches. 220

因此,指出英国整个战略地位在第一次世界大战中暴露出来的弱点,似乎要比详细阐述英国和它的帝国师团、飞机中队和重炮连数量上的大规模增加重要得多。第一个弱点是,尽管英国的地理位置及其大舰队在数量上的优势意味着协约国保持着水面作战的制海权,但是皇家海军远没有做好准备以对付德国于1917年初开始实施的无限制潜艇战。第二个弱点是,虽然英国拥有的一系列相对廉价的战略武器(封锁、军事占领对方的殖民地以及两栖登陆作战等)对于同德国这样一个拥有同盟国的丰富资源的敌人作战似乎不起作用,但采取与德国军队进行直接军事对抗的战略似乎也无法收到效果,并且在人力上要付出更可怕的损失。到1916年11月索姆河战役接近尾声时,英军在那场战役中的伤亡人数已增加到40余万人。尽管这一损失使英国最精良的志愿兵人员丧失殆尽,并使政治家们感到震惊,但却没有使黑格丧失最后胜利的信心。到1917年年中,他又准备从伊普雷向东北方的帕森代尔发动一次攻势,这次攻势成了一场泥沼中的噩梦,英军又伤亡30万人,也使英军在整个法国的许多部队的士气受到了严重挫伤。因此,完全可以预料得到,不管黑格将军和罗伯逊将军怎样抗议,劳埃德·乔治和他满是帝国主义思想的战时内阁却想把更多的英国师调往近东,那里实际的领土利益在召唤,而且可能遭受的损失也要比强攻德军顽强固守的战壕少得多。

Even before Passchendaele, however, Britain had assumed (despite this imperial campaigning) the leadership role in the struggle against Germany. France and Russia might still have larger armies in the field, but they were exhausted by Nivelle’s costly assaults and by the German counterblow to the Brusilov offensive. This leadership role was even more pronounced at the economic level, where Britain functioned as the banker and loan-raiser on the world’s credit markets, not only for itself but also by guaranteeing the monies borrowed by Russia, Italy, and even France—since none of the Allies could provide from their own gold or foreigninvestment holdings anywhere near the sums required to pay the vast surge of imported munitions and raw materials from overseas. By April 1, 1917, indeed, inter-Allied war credits had risen to $4. 3 billion, 88 percent of which was covered by the British government. Although this looked like a repetition of Britain’s eighteenth-century role as “banker to the coalition,” there was now one critical difference: the sheer size of the trade deficit with the United States, which was supplying billions of dollars’ worth of munitions and foodstuffs to the Allies (but not, because of the naval blockade, to the Central Powers) yet required few goods in return. Neither the transfer of gold nor the sale of Britain’s enormous dollar securities could close this gap; only borrowing on the New York and Chicago money markets, to pay the American munitions suppliers in dollars, would do the trick. This in turn meant that the Allies became ever more dependent upon U. S. financial aid to sustain their own war effort. In October 1916, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer was warning that “by next June, or earlier, the President of the American Republic would be in a position, if he wishes, to dictate his terms to us. ”221 It was an altogether alarming position for “independent” Great Powers to be in.

然而,甚至在帕森达勒战役之前,英国就担负起了对德战争的领导角色(尽管它还进行着帝国殖民地战役)。法国和俄国可能在战场上仍拥有更多的军队,但是它们已经被尼韦勒代价巨大的攻势和德军对勃鲁西洛夫攻势发动的反击,搞得精疲力竭。英国的这一领导角色在经济领域里表现得更为明显,在世界信贷市场上,英国发挥着银行家和债权人的职能,不仅是为自己发挥着这一职能,同时还为俄国、意大利甚至法国的借款作担保,因为这几个协约国成员,都无力用它们自己的黄金储备或国外投资债券来支付从海外进口的数额巨大的军火和原料所需要的款项。确实,到1917年4月1日,协约国的战争信贷已经增加到了43亿美元,其中88%都是由英国政府负担的,虽然这看起来像是英国在18世纪充当“联盟的银行家”角色的又一次重演,但这两者之间仍存在着一种关键性的差异,即现在英国和美国之间存在着巨额贸易赤字,因为美国向协约国提供了数十亿美元的军火和粮食(由于海上封锁,没有向同盟国提供),但却很少要求它们用商品来补偿。不论是黄金的转让还是英国持有的巨额美元债券的出售,都不足以弥补这一差额,只有从纽约和芝加哥货币市场上借款,用美元现钞支付美国军火供应商,买卖才能做成。反过来,这又意味着协约国更加依赖美国的财政援助来支持本国的战争努力。1916年10月,英国财政大臣发出警告说:“到下一年6月,或者更早些时候,美利坚合众国总统就会处于只要他愿意就可以对我们发号施令的地位。”对于“独立的”大国来说,这样一种地位简直是令人吃惊的。

But what of Germany? Its performance in the war had been staggering. As Professor Northedge points out, “with no considerable assistance from her allies, [it] had held the rest of the world at bay, had beaten Russia, had driven France, the military colossus of Europe for more than two centuries, to the end of her tether, and in 1917, had come within an ace of starving Britain into surrender. ”222 Part of this was due to those advantages outlined above: good inner lines of communication, easily defensible positions in the west, and open space for mobile warfare against less efficient foes in the east. It was also due to the sheer fighting quality of the German forces, which possessed an array of intelligent, probing staff officers who readjusted to the new conditions of combat faster than those in any other army, and who by 1916 had rethought the nature of both defensive and offensive warfare. 223

德国的情况又怎么样呢?它在战争中的表现是令人吃惊的。正如诺塞奇教授所指出的:“在缺乏来自己方盟国大力援助的情况下,(德国)牵制了整个世界的其余地区,击败了俄国,攻入了法国,这个横行两个多世纪的欧洲军事巨人使尽了浑身解数,在1917年只差一点儿就几乎迫使饥饿中的英国投降了。”它之所以达到这一步,部分是由于上面已提到过的那些有利条件:良好的国内交通线,西线容易固守的阵地,以及东线有利于以机动战打击低能的敌人的开阔地带。此外,还要归功于德国军队优良的战斗素质以及德军所拥有的一大批有智慧而又勇于求新的参谋军官,他们能比其他任何国家军队的参谋军官更快地适应新的作战条件,而且到1916年,他们已对防御战和进攻战的性质作了认真的研究。

Finally, the German state could draw upon both a large population and a massive industrial base for the prosecution of “total war. ” Indeed, it actually mobilized more men than Russia—13. 25 million to 13 million—a remarkable achievement in view of their respective overall populations; and always had more divisions in the field than Russia. Its own munitions production soared, under the watchful eye not only of the high command but of intelligent bureaucrat-businessmen such as Walther Rathenau, who set up cartels to allocate vital supplies and avoid bottlenecks. Adept chemists produced ersatz goods for those items (e. g. , Chilean nitrates) cut off by the British naval blockade. The occupied lands of Luxembourg and northern France were exploited for their ores and coal, Belgian workers were drafted into German factories, Rumanian wheat and oil were systematically plundered following the 1916 invasion. Like Napoleon and Hitler, the German military leadership sought to make conquest pay. 224 By the first half of 1917, with Russia collapsing, France wilting, and Britain under the “counterblockade” of the U-boats, Germany seemed on the brink of victory. Despite all the rhetoric of “fighting to the bitter end,” statesmen in London and Paris were going to be anxiously considering the possibilities of a compromise peace for the next twelve months until the tide turned. 225

最后,德国还可以凭借众多的人口和庞大的工业基础来实施“总体战”。确实,德国实际动员起来的人员比俄国的还要多,1325万人对1300万人;在战场上拥有的师团数量始终比俄国多。考虑到各有关国家的整个人口情况,这可以说是一项了不起的成就。在最高统帅部和像瓦尔特·拉特瑙这样聪明的官僚实业家的严密监督下,德国本国的军火生产迅速猛增。拉特瑙等人建立了卡特尔组织,负责分配极其重要的物资供应和防止出现生产梗塞现象。熟练的化学家们发明了因英国海军封锁而断绝供应的那些原料(如智利的硝酸盐)的代用品。德国还开采了卢森堡和法国北部占领区的矿石和煤炭,并把比利时工人征集到德国工厂中工作,罗马尼亚在1916年遭到德军的入侵以后,其小麦和石油遭到了有计划的掠夺。同拿破仑和希特勒一样,当时的德国军事领导人采取了以战养战的方针。到1917年上半年,随着俄国的崩溃、法国的衰弱和英国处于德国潜艇的“反封锁”打击之下,德国似乎已到达了胜利的边缘。尽管“战斗到底”的华丽辞藻到处喧嚣,伦敦和巴黎的政治家们却一直在焦急地考虑此后12个月里实现某种妥协的和平的可能性,这种情况一直持续到形势发生了根本转变为止。

Yet behind this appearance of Teutonic military-industrial might, there lurked very considerable problems. These were not too evident before the summer of 1916, that is, while the German army stayed on the defensive in the west and made sweeping strikes in the east. But the campaigns of Verdun and the Somme were of a new order of magnitude, both in the firepower employed and the losses sustained; and German casualties on the western front, which had been around 850,000 in 1915, leaped to nearly 1. 2 million in 1916. The Somme offensive in particular impressed the Germans, since it showed that the British were at last making an allout commitment of national resources for victory in the field; and it led in turn to the so-called Hindenburg Program of August 1916, which proclaimed an enormous expansion in munitions production and a far tighter degree of controls over the German economy and society to meet the demands of total war. This combination of on the one hand an authoritarian regime exercising all sorts of powers over the population and on the other a great growth in government borrowing and printing of paper money rather than raising income and dividend taxes—which, in turn, produced high inflation—dealt a heavy blow to popular morale—an ingredient in grand strategy which Ludendorff was far less equipped to understand than, say, a politician like Lloyd George or Clemenceau.

然而,在条顿人的军事与工业力量的这种外表后面,却潜伏着相当严重的问题。这些问题在1916年夏季之前,即德军在西线保持防御态势、在东线实施毁灭性打击的时候,还不太明显。但是,凡尔登战役和索姆河战役改变了这一切,无论是从所使用的火力来看,还是从所遭受的损失来看,都是如此。德国在西线的伤亡,1915年为85万人左右,到1916年便猛增到近120万人。特别是索姆河攻势给德国人留下了颇为深刻的印象,因为这次战役表明,英国人最后把国家资源毫无保留地投入了战场,以争取胜利。反过来说,索姆河战役还导致了1916年8月所谓兴登堡[17]计划的出笼,这项计划宣布要大幅度地增加军火生产,并对德国的经济和社会进行更严密的控制,以满足总体战的需要。一方面是独裁政权对全体国民行使着种种权力,另一方面是政府大量举债和滥发纸币而不是提高收入所得税和股息税。这两种情况反过来又造成了严重的通货膨胀。这些因素综合起来严重地打击了民众士气,而民众士气却是大战略的一个重要组成部分,对于这一点,劳埃德·乔治或克里孟梭[18]这样的政治家要比鲁登道夫明白得多。

Even as an economic measure, the Hindenburg Program had its problems. The announcement of quite fantastic production totals—doubling explosives output, trebling machine-gun output—led to all sorts of bottlenecks as German industry struggled to meet these demands. It required not only many additional workers, but also a massive infrastructural investment, from new blast furnaces to bridges over the Rhine, which further used up labor and resources. Within a short while, therefore, it became clear that the program could be achieved only if skilled workers were returned from military duty; accordingly, 1. 2 million were released in September 1916, and a further 1. 9 million in July 1917. Given the serious losses on the western front, and the still-considerable casualties in the east, such withdrawals meant that even Germany’s large able-bodied male population was being stretched to its limits. In that respect, although Passchendaele was a catastrophe for the British army, it was also viewed as a disaster by Ludendorff, who saw another 400,000 of his troops incapacitated. By December 1917, the German army’s manpower totals were consistently under the peak of 5. 38 million men it had possessed six months earlier. 226

即使作为一项经济措施,兴登堡计划本身也存在着不少问题。完全异想天开的生产总量——使炸药产量增加1倍,使机枪产量增加2倍——的宣布,使德国的工业在挣扎着去满足这些要求时遇到了各种各样的梗塞现象。要满足这些要求不仅需要增加许多工人,而且还需要拿出大量投资去扩充基本设施,从新的冶炼高炉到横跨莱茵河的桥梁都需要投资,这些方面的建设进一步耗尽了德国的劳动力和资源。因此,经过不长时间以后,情况就变得很明朗:只有把熟练工人从军队里抽回来,这一计划才能完成。因此,德国在1916年9月复员了120万人,在1917年7月又复员了190万人。考虑到德军在西线的严重损失以及在东线持续不断的大量伤亡,德国这种从军队里大量复员工人的做法表明,甚至在德国,大量强壮的男性人口也正在达到其使用极限。从这方面来看,尽管帕森达勒战役对于英国军队来说是一次大灾难,但鲁登道夫也把这次战役看成是一次灾难,因为他看到自己的军队又损失了40万战斗力。到1917年12月,德军人员总数一直没有达到它6个月前所拥有的538万人的最高额。

The final twist in the Hindenburg Program was the chronic neglect of agriculture. Here, even more than in France or Russia, men and horses and fuel were taken from the land and directed toward the needs of the army or the munitions industry—an insane imbalance, since Germany could not (like France) compensate for such planning errors by obtaining foodstuffs from overseas to make up the difference. While agricultural production plummeted in Germany, food prices spiraled and people everywhere complained about the scarcity of food supplies. In one scholar’s severe judgment, “by concentrating lopsidedly on producing munitions, the military managers of the German economy thus brought the country to the verge of starvation by the end of 1918. ”227

兴登堡计划的最后一个缺陷,就是长期忽视农业。在德国,这一点甚至比在法国或俄国还要严重,人员、马匹和燃料被从土地上拿走去满足军队或军火工业的需要。这是一种极其愚蠢的片面的做法,因为德国不能(像法国那样)通过从海外取得粮食供应来弥补这一不足。当德国农业生产猛烈下降的时候,食品价格便螺旋式上涨,人们到处都在抱怨食品供应短缺。一位学者做出严厉判断说:“由于片面地集中力量发展军火生产,德国经济的管理者们就这样在1918年底把国家带到了饥饿的边缘。”

But that time was an epoch away from early 1917, when it was the Allies who were feeling the brunt of the war and when, indeed, Russia was collapsing in chaos and both France and Italy seemed not far from that fate. It is in this grandstrategical context, of each bloc being exhausted by the war but of Germany still possessing an overall military advantage, that one must place the high command’s inept policies toward the United States in the first few months of 1917. That the American polity was leaning toward the Allied side even before then was no great secret; despite occasional disagreements over the naval blockade, the general ideological sympathy for the Allied democracies and the increasing dependence of U. S. exporters upon the western European market had made Washington less than completely neutral toward Germany. But the announcement of the unrestricted Uboat campaign against merchant shipping and the revelations of the secret German offers to Mexico of an alliance (in the “Zimmermann Telegram”) finally brought Wilson and the Congress to enter the war. 228

但是,1917年初离那个时刻的到来还有一段距离,当时正在承受战争正面冲击的是协约国;确实,俄国正在混乱中走向崩溃,而法国和意大利似乎离那种噩运也都不太远了。各个集团都被战争拖得精疲力竭,但德国在总体上却仍拥有军事优势——人们必须在这种大战略背景下,来看待最高统帅部在1917年的头几个月对美国采取的愚蠢政策。美国的政策倾向于协约国一方,这一点甚至在那以前就不是什么大的秘密。尽管在海军封锁问题上偶尔存在着争执,但是一般说来在意识形态上美国还是同情协约国民主国家的。美国的出口商日益依赖西欧市场,这就使得华盛顿不能完全对德国保持中立。但是,德国宣布对商船运输实施无限制潜艇战和德国秘密地建议与墨西哥结盟事件的披露,最后把威尔逊[19]和美国国会卷入了战争。

The significance of the American entry into the conflict was not at all a military one, at least for twelve to fifteen months after April 1917, since its army was even less prepared for modern campaigning than any of the European forces had been in 1914. But its productive strength, boosted by the billions of dollars of Allied war orders, was unequaled. Its total industrial potential and its share of world manufacturing output was two and a half times that of Germany’s now overstrained economy. It could launch merchant ships in their hundreds, a vital requirement in a year when the U-boats were sinking over 500,000 tons a month of British and Allied vessels. It could build destroyers in the astonishing time of three months. It produced half of the world’s food exports, which could now be sent to France and Italy as well as to its traditional British market.

美国参战的重要性绝不完全表现在军事方面,至少在1917年4月以后的12到15个月里是这样,因为美国军队为现代战争进行的准备,甚至还不如1914年的各欧洲国家军队。但是,它的生产能力——为协约国战争订货所刺激起来的生产能力,却是无可匹敌的。它的总体工业潜力和它在世界制造业产量中所占的份额,是德国当时过度紧张的经济的2.5倍。它可以使成百艘的商船下水,这在德国潜艇平均每日击沉50万吨英国和其他协约国商船的那一年里,是一种至关重要的需要。它能够在3个月这样惊人的短时间里建造出多艘驱逐舰来。世界粮食出口量的一半是由美国生产的,现在它可以把这些粮食运往法国和意大利,也可以送往其传统的英国市场。

In terms of economic power, therefore, the entry of the United States into the war quite transformed the balances, and more than compensated for the collapse of Russia at this same time. As Table 24 (which should be compared with Table 22) demonstrates, the productive resources now arranged against the Central Powers were enormous.

因此,从经济力量方面来说,美国的参战完全改变了当时的力量对比,而不仅仅是弥补了与此同时发生的俄国崩溃后的局面。正如表24所表明的(应该与表22对比来看),用来打击同盟国的生产资源是巨大的。

Table 24. Industrial/Technological Comparisons with the United States but Without Russia

表24 减去俄国加上美国之后两大集团的工业和技术力量比较表

Because of the “lag time” between turning this economic potential into military effectiveness, the immediate consequences of the American entry into the war were mixed. The United States could not, in the short time available, produce its own tanks, field artillery, and aircraft at anything like the numbers needed (and in fact it had to borrow from France and Britain for such heavier weaponry); but it could continue to pour out the small-arms munitions and other supplies upon which London, Paris, and Rome depended so much. And it could take over from the bankers the private credit arrangements to pay for all these goods, and transform them into intergovernmental debts. Over the longer term, moreover, the U. S. Army could be expanded into a vast force of millions of fresh, confident, well-fed troops, to be thrown into the European balance. 229 In the meanwhile, the British had to grind their way through the Passchendaele muds, the Russian army had disintegrated, German reinforcements had permitted the Central Powers to deal a devastating blow to Italy at Caporetto, and Ludendorff was withdrawing some of his forces from the east in order to launch a final strike at the weakened Anglo-French lines. Outside of Europe, it was true, the British were making important gains against Turkey in the Near East. But the capture of Jerusalem and Damascus would be poor compensation for the loss of France, if the Germans at last managed to do in the west what they had done everywhere else in Europe.

由于把表24中的经济潜力转变成有效的军事力量要有一段“间隔时间”,人们有时对美国参战的直接后果搞不清楚。在可以利用的短时间内,美国无论如何也不可能生产出自己所需要的那么多坦克、野战火炮和飞机来(事实上,它还不得不从英国和法国那里借用这类重型武器),但是它可以源源不断地输送伦敦、巴黎和罗马急需的轻武器弹药以及其他补给物资。而且,它还可以从银行家那里接受私人信贷安排以支付所有这些物品的开支,并把它们转换成政府间的债务。此外,经过较长一段时间以后,美国军队还可以扩充成一支数百万人的、充满自信心的、供应充足的庞大生力军,投入到欧洲的抗衡斗争之中。与此同时,英国人不得不苦苦地寻求走出帕森达勒泥沼的途径,俄国的军队瓦解了,德国的援军使其同盟国能够在卡波雷托对意大利军实施一次毁灭性的打击,而鲁登道夫则正在把他东线的部分军队调到西线,以便对已遭到削弱的英法战线实施最后一次打击。确实,在欧洲以外,英国人在近东与土耳其的作战正在取得重大进展。但是,占领耶路撒冷和大马士革远不足以补偿法国的丧失,如果德国人最后在西线想方设法取得他们在欧洲其他地区曾经取得的那种战绩,法国很可能会沦陷。

This was why the leaderships of all of the major belligerents saw the coming campaigns of 1918 as absolutely decisive to the war as a whole. Although Germany had to leave well over a million troops to occupy its new great empire of conquest in the east, which the Bolsheviks finally acknowledged in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), Ludendorff had been switching forces westward at the rate of ten divisions a month since early November 1917. By the time the German war machine was poised to strike, in late March 1918, it had a superiority of almost thirty divisions over the Anglo-French forces, and many of its units had been trained by Bruchmüller and other staff officers in the new techniques of surprise “storm trooper” warfare. If they succeeded in punching a hole through the Allied lines and driving to Paris or the Channel, it would be the greatest military achievement in the war. But the risks also were horrendous, for Ludendorff was mobilizing the entire remaining resources of Germany for this single campaign; it was to be “all or nothing,” a gamble of epic proportions. Behind the scenes, the German economy was weakening ominously. Its industrial output was down to 57 percent of the 1913 level. Agriculture was more neglected than ever, and poor weather contributed to the decline in output; the further rise in food prices increased domestic discontents. The overworked rolling stock was by now unable to move anything like the amount of raw materials from the eastern territories that had been planned. Of the 192 divisions Ludendorff deployed in the west, 56 were labeled “attack divisions,” in its way a disguise for the fact that they would receive the lion’s share of the diminishing stocks of equipment and ammunition. 230 It was a gamble which the high command believed had to succeed. But if the attack failed, German resources would be exhausted—and that just at the time when the Americans were at last capable of pouring nearly 300,000 troops a month into France, and the unrestricted U-boat campaign had been completely checked by the Allied convoys.

正因为如此,所有主要交战国的领导人都认为,1918年即将来临的战局,对整个战争具有绝对的决定性意义。虽然德国不得不留下100多万军队在东线以占领其新征服的庞大帝国,这一帝国在布列斯特-立托夫斯克和约(1918年3月)中最后得到了布尔什维克的承认,但是自1917年11月初以来,鲁登道夫平均每月以10个师的速度从东线向西线抽调兵力。到1918年3月末,德国战争机器做好发动进攻的准备时,德军在兵力上占有比英法联军几乎多30个师的优势,其中许多部队都在布鲁赫米勒和其他参谋军官的指导下接受了“暴风突击队”式的突然袭击的战术训练。德军要是能够成功地突破协约国防线,并向巴黎或海峡挺进,它本来会取得这场战争中最大的军事成就。但是,其风险也是可怕的,因为鲁登道夫正在把德国剩余的全部资源动员起来用于这场交战——一场特大规模的“要么全赢、要么输光”的赌博。在幕后,德国经济正在不祥地走向衰落。它的工业产量降到只占1913年水平的57%。农业生产更加受到忽视,恶劣的气候又使其产量进一步下降;而食品价格的进一步上涨更加引起了国内的不满。负担过重的铁路运输车辆到现在已经无法按预定计划从东部占领地西运原料。鲁登道夫部署在西线的192个师中,有56个师被指定为“攻击师”,其中隐藏着这样一个事实,即这些部队将获得正在日益减少的装备和弹药储备的最大份额。这是一次德军最高统帅部认为只许成功的赌博。但是,如果这次进攻失败了,德国的资源将消耗殆尽——正是在这个时候,美国人最后终于能够以每月近30万人的速度向法国输送部队,而德国的无限制潜艇战也完全被协约国的护航队制止了。

Ludendorff’s early successes—crushing the outnumbered British Fifth Army, driving a wedge between the French and British forces, and advancing by early June 1918 to within thirty-seven miles of Paris in another one of his lunges—frightened the Allies into giving Foch supreme coordination of their Western Front forces, sending reinforcements from England, Italy, and the Near East, and again (privately) worrying about a compromise peace. Yet the fact was that the Germans had overextended themselves, and suffered the usual consequences of going from the defensive to the offensive. In the first two heavy blows against the British sector, for example, they had inflicted 240,000 British and 92,000 French casualties, but their own losses had risen to 348,000. By July, “the Germans lost about 973,000 men, and over a million more were listed as sick. By October there were only 2. 5 million men in the west and the recruiting situation was desperate. ”231 From mid-July onward, the Allies were superior, not simply in fresh fighting men, but even more so in artillery, tanks, and aircraft—allowing Foch to orchestrate a whole series of offensives by British Empire, American, and French armies so that the weakening German forces would be given no rest. At the same time, too, the Allies’ military superiority and greater staying power was showing itself in impressive victories in Syria, Bulgaria, and Italy. All at once, in September/October 1918, the entire German-led bloc seemed to a panic-stricken Ludendorff to be collapsing, internal discontent and revolutions now interacting with the defeats at the front to produce surrender, chaos, and political upheaval. 232 Not only was the German military bid finished, therefore, but the Old Order in Europe was ruined as well.

鲁登道夫在这次攻势的开始阶段取得了成功,他打垮了在人数上占优势的英国第5集团军,在法军和英军防线之间楔入对方纵深,并在1918年6月初的另一次猛烈突破中前进到距巴黎37英里的地方。德军的这些胜利使协约国感到惊恐,迫使它们不得不授予福煦西线部队的最高协调权,从英国、意大利和近东增调援兵,并再一次(私下)考虑实现妥协的可能性。然而,事实是德军的战线延伸过长,因而不得不接受从防御转入进攻通常所产生的后果。例如,对英国防区的最初两次沉重打击,使英军和法军分别遭受了24万人和9.2万人的伤亡,但德军自己的损失也高达34.8万人。到7月份,“德军损失了大约97.3万人,并有100多万人列入了病号名单。到10月份,西线德军只剩下了250万人,而新兵征募情况却令人绝望”。从7月中旬起,协约国一方开始占据优势,这不仅表现在新增加的战斗人员方面,而且更多地表现在火炮、坦克和飞机方面。这就使得福煦能够周密地组织实施由英帝国军队、美军和法军共同参加的一系列攻势,使日益削弱的德军无喘息之机。与此同时,协约国的军事优势和更大的持久作战能力,还表现在它们的军队在叙利亚、保加利亚和意大利取得的给人深刻印象的胜利上。所有这一切突然导致1918年9~10月间出现这样的局面:对于惊慌失措的鲁登道夫来说,整个德国的领导集团似乎正在走向崩溃。现在,德国国内的不满和革命与前线的失败相互作用,导致了投降、混乱和政治动荡。因此,不仅德国的军事企图已成泡影,整个欧洲的旧秩序也被破坏了。

In the light of the awful individual losses, suffering, and devastation which had occurred both in “the face of battle” and on the home fronts,233 and of the way in which the First World War has been seen as a self-inflicted death blow to European civilization and influence in the world,234 it may appear crudely materialistic to introduce another statistical table at this point (Table 25). Yet the fact is that these figures point to what has been argued above: that the advantages possessed by the Central Powers—good internal lines, the quality of the German army, the occupation and exploitation of many territories, the isolation and defeat of Russia— could not over the long run outweigh this massive disadvantage in sheer economic muscle, and the considerable disadvantage in the size of total mobilized forces. Just as Ludendorff’s despair at running out of able-bodied troops by July 1918 was a reflection of the imbalance of forces, so the average Frontsoldat’s amazement at how well provisioned were the Allied units which they overran in the spring of that year was an indication of the imbalance of production. 236

考虑到在“战场上”和在国内战线上人们所遭受的可怕的损失、痛苦和蹂躏,考虑到人们认为第一次世界大战对欧洲文明及其在世界上的影响是一次自己施加的致命打击这一观点,在这方面列出另一份统计表(表25)看起来似乎是太唯物主义了,但事实上表中的这些数字可以说明上面论述的全部内容:同盟国所拥有的有利条件——良好的国内交通线、德军的素质、对许多土地的占领和开发利用,以及俄国的孤立和失败——从长远看终究不能抵消德国在纯经济力量方面所存在的巨大劣势,也不能抵消动员起来的总兵力上所存在的相当严重的劣势。如果说鲁登道夫对于到1918年7月德军精锐部队正在耗尽一事感到绝望,是对力量对比失去平衡这种情况的一种反映,那么,那一年春季饱尝饥饿之苦的普通德国前线士兵,对他们曾经打击过的协约国部队有那么好的物资供应感到惊奇,也正是对生产上失去平衡的一种反映。

Table 25. War Expenditure and Total Mobilized Forces, 1914-1919 235

表25 战争开支和动员起来的总兵力一览表(1914~1919年)

*Belgium, Rumania, Portugal, Greece, Serbia.

*包括比利时、罗马尼亚、葡萄牙、希腊、塞尔维亚

While it would be quite wrong, then, to claim that the outcome of the First World War was predetermined, the evidence presented here suggests that the overall course of that conflict—the early stalemate between the two sides, the ineffectiveness of the Italian entry, the slow exhaustion of Russia, the decisiveness of the American intervention in keeping up the Allied pressures, and the eventual collapse of the Central Powers—correlates closely with the economic and industrial production and effectively mobilized forces available to each alliance during the different phases of the struggle. To be sure, generals still had to direct (or misdirect) their campaigns, troops still had to summon the individual moral courage to assault an enemy position, and sailors still had to endure the rigors of sea warfare; but the record indicates that such qualities and talents existed on both sides, and were not enjoyed in disproportionate measure by one of the coalitions. What was enjoyed by one side, particularly after 1917, was a marked superiority in productive forces. As in earlier, lengthy coalition wars, that factor eventually turned out to be decisive.

然而,如果认为第一次世界大战的结局是预先注定的,那就大错特错了,这里所提出的证据表明,这场战争的全部进程——早期阶段双方的僵持、意大利参战的微小作用、俄国实力的缓慢枯竭、美国参战在保持协约国压力方面的决定性意义,以及同盟国的最后崩溃——与每个联盟在这场斗争的各个时期的经济和工业生产以及有效动员起来可供使用的兵力,有着密切的相互关系。可以肯定地说,将军们仍须指挥(或错误地指挥)他们的战役,部队仍须唤起每个人的道义勇气以便向敌人的阵地发起冲击,水兵们仍须忍受海战的艰苦,但是历史记录表明,这些素质和才能是战争双方所共有的,而不为哪一个联盟以不相称的比例所独享。为一方所独享的是生产力上的显著优势,1917年以后尤其如此。和早些时候一样,在长期的联盟战争中,这一因素最终会变得具有决定性的意义。

*E. g. , shares of world trade, which disproportionately boost the position of maritime, trading nations, and underemphasize the economic power of states with a large degree of self-sufficiency.

[1]?科布登(1804~1865年),英国下院议员,以鼓吹自由贸易和自由竞争而著称。——审校者注

*Britain would be “benevolently neutral” to Japan if the latter was fighting one foe, but had to render military aid if it was fighting more than one; France’s agreement to assist Russia was similarly phrased. Unless London and Paris both agreed to stay out, therefore, their new found friendship would be ruined.

[2]?例如,在世界贸易中所占的份额会不相称地提高海上贸易国的地位,低估在很大程度上自给自足的国家的经济实力。

*Not surprisingly, since the Russians were incredibly careless with their wireless transmissions.

[3]?乔利蒂(1842~1928年),意大利政治家,从1892年到1921年曾先后5次出任总理,在国内进行了一些改革,对外进行殖民扩张。——审校者注

[4]?廷巴克图,在非洲马里共和国。——审校者注

[5]?东京,这里是指越南。——审校者注

[6]?阿散蒂是非洲加纳的一个地区。——审校者注

[7]?维多利亚女王(1819~1901年),1837年即位。——审校者注

[8]?小毛奇(1848~1916年),名约翰内斯·路德维希,是卡尔·毛奇之侄。1906~1914年任德军总参谋长。——审校者注

[9]?这里是指美国参加八国联军镇压义和团起义。——审校者注

[10]?如果日本只同一国发生战争,英国将保持“善意的中立”;如果日本同一个以上的国家发生战争,英国则提供军事援助。法国援助俄国协定也有类似的条款。因此除非英法两国共同置身于日俄战争之外,否则刚刚建立的友好关系就会丧失。

[11]?阿尔赫西拉斯,西班牙南部港口城市,在直布罗陀附近。——审校者注

[12]?法金汉(1861~1922年),德国将军。1900年曾参加八国联军镇压义和团起义。第一次世界大战开始不久任德军总参谋长。凡尔登战役失败后被撤职。——审校者注

[13]?鲁登道夫(1865~1937年),德国将军。第一次大战初期任集团军参谋长等职。1916年8月升任德军总监督,实际上与兴登堡共掌军权。——审校者注

[14]?劳埃德·乔治(1863~1945年),旧译劳合·乔治。英国自由党领袖,1916~1922年任首相,后任贸易大臣、财政大臣等职。——审校者注

[15]?这毫不奇怪,俄国人对于他们的无线电通信的粗心大意简直令人难以置信。

[16]?福煦(1851~1929年),法国元帅。第一次世界大战初期任军长、集团军司令等职。1917年5月任法军总参谋长。1918年3月负责协调协约国在西线的军事行动,5月正式就任协约国军总司令。——译者注

[17]?兴登堡(1847~1934年),德国元帅,1916年8月任德军总参谋长、陆军总司令。1925~1934年任德国总统。——译者注

[18]?克里孟梭(1841~1929年),法国总理(1906~1909年、1917~1920年在任)。1917年11月出任战时内阁总理兼陆军部长,提出“一切服从战争”的口号,后被誉为“胜利之父”。——审校者注

[19]?托马斯·伍德罗·威尔逊(1856~1924年),美国总统(1913~1921年在任)。民主党人。1917年4月对德宣战,次年1月倡议建立国际联盟,并提出结束战争的“十四点”纲领。——审校者注