The Postwar International Order

战后国际秩序

The statesmen of the greater and lesser powers assembling in Paris at the beginning of 1919 to arrange a peace settlement were confronted with a list of problems both more extensive and more intractable than had been encountered by any of their predecessors in 1856,1814–1815, and 1763. While many items on the agenda could be settled and incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles itself (June 28, 1919), the confusion prevailing in eastern Europe as rival ethnic groups jostled to establish “successor states,” the civil war and interventions in Russia, and the Turkish nationalist reaction against the intended western division of Asia Minor meant that many matters were not fixed until 1920, and in some cases 1923. However, for the purposes of brevity, this group of agreements will be examined as a whole, rather than in the actual chronological order of their settlement.

1919年初,大大小小的国家的政治家们云集巴黎,磋商和平解决办法。他们面临的一系列难题,要比他们的前辈在1856年、1814~1815年和1763年所遇到的问题更为广泛、更为棘手。虽然议事日程上的许多问题都可以列入《凡尔赛和约》(1919年6月28日签订)加以解决,但是,敌对的种族集团竞相建立“继承人国家”而在东欧造成一片混乱,俄国的内战和外来干涉,以及土耳其民族主义者对于西方企图瓜分小亚细亚所做出的反应都表明,直到1920年,许多问题还没有得到解决,甚至有些问题到1923年仍为悬案。为了简单明了起见,我们将把这一系列协议作为一个整体,而不是按照它们实际付诸实施的年代顺序来考查。

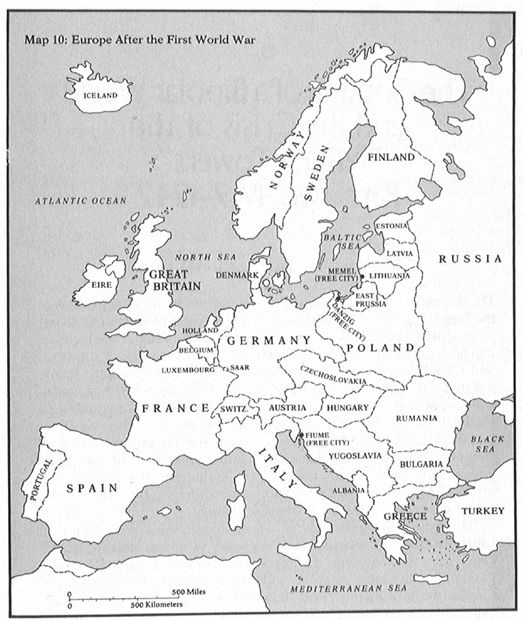

The most striking change in Europe, measured in territorial-juridical terms, was the emergence of a cluster of nation-states—Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—in place of lands which were formerly part of the Habsburg, Romanov, and Hohenzollen empires. While the ethnically coherent Germany suffered far smaller territorial losses in eastern Europe than either Soviet Russia or the totally dissolved Austro-Hungarian Empire, its power was hurt in other ways: by the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, and by border rectifications with Belgium and Denmark; by the Allied military occupation of the Rhine-land, and the French economic exploitation of the Saarland; by the unprecedented “demilitarization” terms (e. g. , minuscule army and coastal-defense navy, no air force, tanks, or submarines, abolition of Prussian General Staff); and by an enormous reparations bill. In addition, Germany also lost its extensive colonial empire to Britain, the self-governing dominions, and France— just as Turkey found its Near East territories turned into British and French mandates, distantly supervised by the new League of Nations. In the Far East, Japan inherited the former German island groups north of the equator, although it returned Shantung to China in 1922. At the 1921–1922 Washington Conference, the powers recognized the territorial status quo in the Pacific and Far East, and agreed to restrict the size of their battle fleets according to relative formulae, thereby heading off an Anglo-American-Japanese naval race. In both the West and the East, therefore, the international system appeared to have been stabilized by the early 1920s—and what difficulties remained (or might arise in the future) could now be dealt with by the League of Nations, which met regularly at Geneva despite the surprise defection of the United States. 1

如果按照领土—法律标准来衡量,欧洲最引人注目的变化,可以说是在先前属于哈布斯堡帝国、罗曼诺夫帝国和霍亨索伦帝国的土地上出现了一系列民族国家,这些国家是波兰、捷克斯洛伐克、奥地利、匈牙利、南斯拉夫、芬兰、爱沙尼亚、拉脱维亚和立陶宛。种族上凝聚在一起的德国,在东欧丧失的领土比苏维埃俄国和完全瓦解的奥匈帝国都要小得多。但它的力量在其他方面遭到了削弱,其中包括将阿尔萨斯—洛林归还法国,同比利时和丹麦进行了边界调整,盟军占领了莱茵兰,法国对于萨尔的经济剥削,史无前例的“非军事化”条款(即只得保有规模极小的陆军和近岸防卫的海军,不得保有空军、坦克或潜艇,撤销普鲁士总参谋部等),以及巨额赔款。此外,德国还将其广大的殖民帝国丢给了英国、自治领和法国,正像土耳其发现自己的近东领土变成了英国和法国的委任统治地、在形式上受到新建国际联盟的监督一样。在远东,日本虽然在1922年将山东归还了中国,但却接管了先前属于德国的位于赤道以北的岛屿群。在1921~1922年召开的华盛顿会议上,各国承认了太平洋和远东地区的领土现状,并同意根据相对标准来限制各自的作战舰队的规模,从而阻止了英、美、日三国的海军军备竞赛。因此,到20世纪20年代初,无论在西方还是在东方,国际体系已趋于稳定。所遗留的难题(或者今后可能出现的问题),都可以通过国际联盟来处理;尽管美国没有加入,国际联盟仍定期在日内瓦举行会议。

The sudden American retreat into at least relative diplomatic isolationism after 1920 seemed yet another contradiction to those world-power trends which, as detailed above, had been under way since the 1890s. To the prophets of world politics in that earlier period, it was self-evident that the international scene was going to be increasingly influenced, if not dominated, by the three rising powers of Germany, Russia, and the United States. Instead, the first-named had been decisively defeated, the second had collapsed in revolution and then withdrawn into its Bolshevik-led isolation, and the third, although clearly the most powerful nation in the world by 1919, also preferred to retreat from the center of the diplomatic stage. In consequence, international affairs during the 1920s and beyond still seemed to focus either upon the actions of France and Britain, even though both countries had been badly hurt by the First World War, or upon the deliberations of the League, in which French and British statesmen were preeminent. Austria-Hungary was now gone. Italy, where the National Fascist Party under Mussolini was consolidating its hold after 1922, was relatively quiescent. Japan, too, appeared tranquil following the 1921–1922 Washington Conference decisions.

1920年后,美国突然退回到至少是相对的外交孤立主义之中,这似乎与上述的、自19世纪90年代以来所形成的世界强国的发展趋势是矛盾的。对那个时期之前的世界政治预言家来说,国际舞台将日益受到正在兴起的德国、俄国和美国的影响(如果说不是统治的话),这一点不言而喻。然而事实是,这三个国家中的第一个国家遭到了决定性的失败;第二个国家在革命中崩溃了,后来又退回到布尔什维克领导的孤立状态中;而第三个国家,尽管在1919年无疑是世界上最强大的国家,它也宁愿退出外交舞台的中心。结果是,20世纪20年代和以后时期的国际事务似乎仍是以英国和法国的行动为中心,尽管两个国家在第一次世界大战中都遭到了严重的削弱;或者是以国际联盟的审议为中心,而在国际联盟中又是英、法的政治家们扮演着主要角色。奥匈帝国现已消亡。在意大利,1922年以后,墨索里尼领导的国家法西斯党正处在巩固其统治地位的时期,因而显得比较沉默。日本也是一样,似乎是在平静地遵循着1921~1922年华盛顿会议的决定。

In a curious and (as will be seen) artificial way, therefore, it still seemed a Eurocentered world. The diplomatic histories of this period focus heavily upon France’s “search for security” against a future German resurgence. Having lost a special Anglo-American military guarantee at the same time as the U. S. Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, the French sought to create a variety of substitutes: encouraging the formation of an “antirevisionist” bloc of states in eastern Europe (the so-called Little Entente of 1921); concluding individual alliances with Belgium (1920), Poland (1921), Czechoslovakia (1924), Rumania (1926), and Yugoslavia (1927); maintaining a very large army and air force to overawe the Germans and intervening—as in the 1923 Ruhr crisis—when Germany defaulted on the reparation payments; and endeavoring to persuade successive British administrations to provide a new military guarantee of France’s borders, something which was achieved only indirectly in the multilateral Locarno Treaty of 1925. 2 It was also a period of intense financial diplomacy, since the interacting problem of German reparations and Allied war debts bedeviled relations not only between the victors and the vanquished, but also between the United States and its former European allies. 3 The financial compromise of the Dawes Plan (1924) eased much of this turbulence, and in turn prepared the ground for the Locarno Treaty the following year; that was followed by Germany’s entry into the League and then the amended financial settlement of the Young Plan (1929). By the late 1920s, indeed, with prosperity returning to Europe, with the League apparently accepted as an important new element in the international system, and with a plethora of states solemnly agreeing (under the 1928 Pact of Paris) not to resort to war to settle future disputes, the diplomatic stage seemed to have returned to normal. Statesmen such as Stresemann, Briand, and Austen Chamberlain appeared, in their way, the latterday equivalents of Metternich and Bismarck, meeting at this or that European spa to settle the affairs of the world.

因此,从一个难以理解的和(我们将会看到)人为的观点来看,世界似乎仍是一个以欧洲为中心的世界。这一时期的外交史更多地是以法国“寻找安全”以对抗德国未来的复兴为中心的。在美国参议院否决《凡尔赛和约》的同时,法国也失去了英美特殊的军事保证,只好设法寻求各种补救措施,例如,鼓励在东欧形成一个“反修正主义”的国家集团(即1921年所谓的小协约国);与比利时(1920年)、波兰(1921年)、捷克斯洛伐克(1924年)、罗马尼亚(1926年)和南斯拉夫(1927年)等国单独结盟;维持一支庞大的陆军和空军以威慑德国,并在德国不支付赔款时进行干预,就像1923年的鲁尔危机那样;努力说服历届英国政府对法国的边界提供新的军事保证,这一努力仅仅在1925年签订的多国《洛迦诺公约》中间接地取得了一些结果。这一时期还是一个财政外交的紧张时期。由于德国赔款和协约国的战争债务之间相互影响,不仅搅乱了胜利者和被征服者之间的关系,而且也搅乱了美国和它的前欧洲盟国之间的关系。“道威斯计划”(1924年)的财政妥协在很大程度上平息了这场动乱,同时也为第二年《洛迦诺公约》的签订打下了基础;随之而来的是德国加入国际联盟和作为修正了的财政解决方案的“杨格计划”(1929年)的出笼。确实,到20世纪20年代末,由于繁荣又回到了欧洲,国际联盟明显地被当作国际体系中一个重要的新因素,相当多的国家(根据1928年的《巴黎公约》的规定)庄严地同意在解决未来的争端中不诉诸武力,外交舞台似乎已恢复了常态。像施特莱斯曼、白里安和张伯伦这样的政治家们,以他们自己的方式充当着现代的梅特涅和俾斯麦,在欧洲这个或那个游览胜地聚会以解决世界的事务。

Despite these superficial impressions, however, the underlying structures of the post-1919 international system were significantly different from, and much more fragile than, those which influenced diplomacy a half-century earlier. In the first place, the population losses and economic disruptions caused by four and a half years of “total” war were immense. Around 8 million men were killed in actual fighting, with another 7 million permanently disabled and a further 15 million “more or less seriously wounded”4—the vast majority of these being in the prime of their productive life. In addition, Europe excluding Russia probably lost over 5 million civilian casualties through what has been termed “war-induced causes”—“disease, famine and privation consequent upon the war as well as those wrought by military conflict”;5 the Russian total, compounded by the heavy losses in the civil war, was much larger. The wartime “birth deficits” (caused by so many men being absent at the front, and the populations thereby not renewing themselves at the normal prewar rate) were also extremely high. Finally, even as the major battles ground to a halt, fighting and massacres occurred during the postwar border conflicts in, for example, eastern Europe, Armenia, and Poland; and none of these war-weakened regions escaped the dreadful influenza epidemic of 1918–1919, which carried off further millions. Thus, the final casualty list for this extended period might have been as much as 60 million people, with nearly half of these losses occurring in Russia, and with France, Germany, and Italy also being badly hit. There is no known way of measuring the personal anguish and the psychological shocks involved in such a human catastrophe, but it is easy to see why the participants—statesmen as well as peasants—were so deeply affected by it all.

然而,尽管存在着这些表面现象,1919年以后的国际体系的基础结构毕竟不同于半个世纪以前影响外交的那些基础结构,而且前者要比后者脆弱得多。首先,4年半的“总体战”所造成的人口损失和经济破坏是巨大的。在实际战斗中死亡人数大约为800万,另外有700万人永远成了残疾人,还有1500万人“伤得或重或轻”,在这些伤亡者之中,绝大多数人都处在具有生产能力的一生当中的最佳年华。此外,由于那些所谓的“战争诱发的原因”——“战争所引起的和军事冲突所造成的疾病、饥荒和匮乏”,除俄国外,欧洲伤亡平民可能超过500万人;而俄国人的伤亡总数(要是把内战的惨重损失也加在一起的话)要比这大得多。战时“生育赤字”(由于那么多的男人被调往前线,因此人口不能以战前的正常比率更新)也是极高的。最后,虽然大的战役停止了,但在战后边界冲突中,如在东欧、亚美尼亚和波兰的边界冲突中,战斗和屠杀仍没有停止。这些受到战争削弱的地区哪一个也没有逃脱掉1918~1919年那场可怕的流行性感冒的传播,这一灾祸又夺走了数百万人的生命。因此,在这段持久的时期里,受害人数(伤亡人数)总计高达6000万人,其中将近一半的损失发生在俄国,而法国、德国和意大利也受到了严重的损害。目前还没有什么方法可以衡量这场人类浩劫给个人带来的极度痛苦和心理冲击,但是这场浩劫的参与者——从政治家到农民——都受到了深重影响这一点是显而易见的。

The material costs of the war were also unprecedented and seemed, to those who viewed the devastated landscapes of northern France, Poland, and Serbia, even more shocking: hundreds of thousands of houses were destroyed, farms gutted, roads and railways and telegraph lines blown up, livestock slaughtered, forests pulverized, and vast tracts of land rendered unfit for farming because of unexploded shells and mines. When the shipping losses, the direct and indirect costs of mobilization, and the monies raised by the combatants are added to the list, the total charge becomes so huge as to be virtually incomprehensible: in fact, some $260 billion, which, according to one calculation, “represented about six and a half times the sum of all the national debt accumulated in the world from the end of the eighteenth century up to the eve of the First World War. ”6 After decades of growth, world manufacturing production turned sharply down; in 1920 it was still 7 percent less than in 1913, agricultural production was about one-third below normal, and the volume of exports was only around half what it was in the prewar period. While the growth of the European economy as a whole had been retarded, perhaps as much as by eight years,* individual countries were much more severely affected. Predictably, Russia in the turmoil of 1920 recorded the lowest industrial output, equal to a mere 13 percent of the 1913 figure; but in Germany, France, Belgium, and much of eastern Europe, industrial output was at least 30 percent lower than before the conflict. 7

这场战争的物质损失也是空前的,对于那些看到法国北部、波兰和塞尔维亚惨遭蹂躏的景象的人们来说,物质损失更加骇人听闻:无数幢房屋被摧毁,田野一片荒芜,公路、铁路和电报线路都被炸断,牲畜横遭屠杀,森林被彻底摧毁,由于遍布着大量未爆炸的炸弹和地雷,大片田园无法耕种。如果再加上船舶损失、用于动员的直接和间接费用以及各参战国所筹集的款项,这场战争的总消耗实际上高得叫人无法想象。事实上,大约有2600亿美元左右。据估算,这个数字“相当于从18世纪末到第一次世界大战前夕整个世界所有国家债务总和的6.5倍”。在持续几十年的增长以后,世界制造业产量突然下跌。1920年世界制造业产量仍不及1913年的7%,农业产量低于常年的1/3,出口额只及战前时期的一半左右。整个欧洲经济的发展在长达近8年的时间里处于停滞状态[1],个别国家所受到的影响更为严重。可以预料,处于混乱中的俄国在1920年创下了工业产量的最低纪录,只占1913年产量的13%;而德国、法国、比利时和大半个东欧的工业产量至少要比战前低30%。

If some societies were the more heavily affected by the war, then others of course escaped lightly—and many improved their position. For the fact was that modern war, and the industrial productivity generated by it, also had positive effects. In strictly economic and technological terms, these years had seen many advances: in automobile and truck production, in aviation, in oil refining and chemicals, in the electrical and dyestuff and alloy-steel industries, in refrigeration and canning, and in a whole host of other industries. 8 Naturally, it proved easier to develop and to benefit commercially from such advances if one’s economy was far from the disruption of the front line; which is why the United States itself, but also Canada, Australia, South Africa, India, and parts of South America, found their economies stimulated by the industrial, raw-material, and foodstuffs demand of a Europe convulsed by a war of attrition. As in previous mercantilist conflicts, one country’s loss was often another’s gain—provided the latter avoided the costs of war, or was at least protected from the full blast of battle.

如果说一些国家受到这场战争的影响更为深重的话,那么毫无疑问,其他国家所受到的影响就较轻,而且许多国家经过这场战争反而改善了它们的地位。因为事实是,现代战争和被现代战争所刺激起来的工业生产力也有积极作用。严格地从经济和技术角度来说,这些年取得了很多进步,具体表现在汽车和卡车生产、飞机制造业、炼油和化学制品、电力工业、染料工业和合金钢工业、冷藏法和罐头食品的制造以及其他许多工业部门。很自然,如果一个国家的经济远离前线的破坏,那么事实证明,它是很容易利用这些进步并从这些进步中获得商业利益的。这就是饱受消耗战之苦的欧洲对于工业品、原材料和粮食的需求,刺激了美国、加拿大、澳大利亚、南非、印度和南美部分国家经济发展的原因所在。和从前重商主义的冲突一样,一个国家的损失通常使另一个国家受益,如果后者能够避免战争消耗,或者至少能够防止发生大规模的交战的话(见表26)。

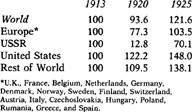

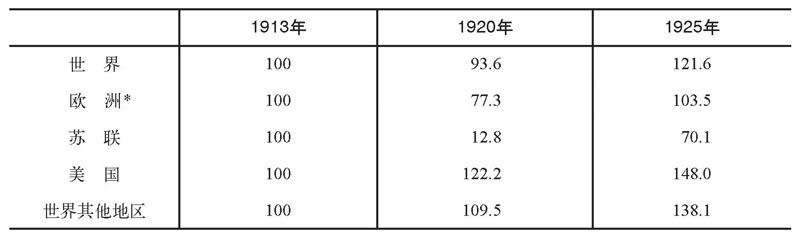

Table 26. World Indices of Manufacturing Production, 1913-19259

表26 世界制造业生产指数(1913~1925年)

*包括英国、法国、比利时、荷兰、德国、丹麦、挪威、瑞典、芬兰、瑞士、奥地利、意大利、捷克斯洛伐克、匈牙利、波兰、罗马尼亚、希腊和西班牙。

Such figures on world manufacturing production are very illuminating in this respect, since they record the extent to which Europe (and especially the USSR) were hurt by the war, while other regions gained substantially. To some degree, of course, the spread of industrialization from Europe to the Americas, Japan, India, and Australasia, and the increasing share of these latter territories in world trade, was simply the continuation of economic trends which had been in evidence since the late nineteenth century. Thus, according to one arcane calculation already mentioned earlier, the United States pre-1914 growth was such that it probably would have overtaken Europe in total output in the year 1925;10 what the war did was to accelerate that event by a mere six years, to 1919. On the other hand, unlike the 1880–1913 changes, these particular shifts in the global economic balances were not taking place in peacetime over several decades and in accord with market forces. Instead, the agencies of war and blockade created their own peremptory demands and thus massively distorted the natural patterns of world production and trade. For example, shipbuilding capacity (especially in the United States) had been enormously increased in the middle of the war to counter the sinkings by U-boats; but after 1919–1920, there were excess berths across the globe. Again, the output of the steel industries of continental Europe had fallen during the war, whereas that of the United States and Britain had risen sharply; but when the European steel producers recovered, the excess capacity was horrific. This problem also affected an even greater sector of the economy—agriculture. During the war years, farm output in continental Europe had shriveled and Russia’s prewar export trade in grain had disappeared, whereas there had been large increases in output in North and South America and in Australasia, whose farmers were the decided (if unpremeditating) beneficiaries of the archduke’s death. But when European agriculture recovered by the late 1920s, producers across the world faced a fall-off in demand, and tumbling prices. 11 These sorts of structural distortions affected all regions, but were felt nowhere as severely as in east-central Europe, where the fragile “successor states” grappled with new boundaries, dislocated markets, and distorted communications. Making peace at Versailles and redrawing the map of Europe along (roughly) ethnic lines did not of itself guarantee a restoration of economic stability.

关于世界制造业生产的这些数字在这方面很能说明问题,因为它们记录了在其他地区取得巨大进步的同时,欧洲(特别是苏联)在这场战争中遭受损害的程度。毫无疑问,从一定程度上来说,工业化从欧洲向美洲、日本、印度和澳大拉西亚[2]扩展,使得这些地区在世界贸易额的比重日益增长,仅仅是19世纪末期以来就显露出的经济发展趋势的持续上升。因此,根据上文已提到的那种计算方法来计算,美国在1914年以前经济的增长量可能已经超过了欧洲1925年的总产量。这场战争所起的作用,只是用仅仅6年的时间(即到1919年)加速了那一事变。另一方面,和1880~1913年的变化不同,全球经济力量对比中的这些特殊变化并不是发生在几十年的和平时期,也不是以市场力量的大小为转移的。相反,战争和封锁的作用就在于形成了它们自己独特的需求,因而大大改变了世界生产和贸易的自然模式。例如,在战争中期,为了弥补被潜艇所击沉的船只,造船能力(特别是美国的造船能力)得到了巨大的增强,但是1919~1920年以后,在全球航行的船只就出现了过剩现象。又如,在战争期间欧洲大陆的钢产量下降了,而美国和英国的钢产量却迅速增加,但是当欧洲的钢的生产者恢复元气以后,这种过剩的生产力是极其可怕的。这一问题也影响到了一个更大的经济部门—农业。在战争期间,欧洲大陆的农业产量减少了,俄国的战前谷物出口贸易也消失了,然而,南北美洲和大洋洲的农业产量却有了巨大的增加,它们的农民成了奥匈帝国皇太子之死当然的(如果不是预谋的)受益人。但是,到20世纪20年代后期欧洲农业得到恢复以后,整个世界的农业生产者则面临着对农作物需求量减少、价格日益下跌的困境。这些结构性的变化对所有地区都产生了影响,但在东欧和中欧地区,这种影响尤为强烈,因为在那里,脆弱的“继承者国家”正在为解决新的国界、混乱的市场和交通而疲于奔命。凡尔赛创造的和平和按照(大致地按照)种族界线重新划定的欧洲版图本身,并没有为恢复经济稳定提供保证。

Finally, the financing of the war had caused economic—and later political— problems of unprecedented complexity. Very few of the belligerents (Britain and the United States were among the exceptions) had tried to pay for even part of the costs of the conflict by increasing taxes; instead most states relied almost entirely on borrowing, assuming that the defeated foe would be forced to meet the bill—as had happened to France in 1871. Public debts, now uncovered by gold, rose precipitously; paper money, pouring out of the state treasuries, sent prices soaring. 12 Given the economic devastation and territorial dislocations caused by the war, no European country was ready to follow the United States back onto the gold standard in 1919. Lax monetary and fiscal policies caused inflation to keep on increasing, with disastrous results in central and eastern Europe. Competitive depreciations of the national currency, carried out in a desperate attempt to boost exports, simply created more financial instability—as well as political rivalry. This was all compounded by the intractable related issues of intra-Allied loans and the victors’ (especially France’s) demand for substantial German reparations. All the European allies were in debt to Britain, and to a lesser extent to France; while those two powers were heavily in debt to the United States. With the Bolsheviks’ repudiating Russia’s massive borrowings of $3. 6 billion, with the Americans asking for their money back, with France, Italy, and other countries refusing to pay off their debts until they had received reparations from Germany, and with the Germans declaring that they could not possibly pay the amounts demanded of them, the scene was set for years of bitter wrangling, which sharply widened the gap in political sympathies between western Europe and a disgruntled United States. 13

最后,战争的财政支出引起了空前复杂的经济问题以及随之而来的政治问题。很少有几个交战国(英国和美国例外)曾试图通过增加税收来偿付这场战争的部分费用;相反,大多数国家都几乎完全依赖于借款,并设想由战败国来偿还这些债务——像1871年法国所做的那样。没有黄金保险的公债在直线上升,国家财政部源源不断抛出的纸币使物价飞涨。由于战争所造成的经济破坏和领土变更,1919年欧洲各国都不准备跟随美国恢复金本位。松散的货币和财政政策造成了通货膨胀的持续增长,这在中欧和东欧导致了灾难性的后果。各国孤注一掷地试图增加出口而执行国家通货贬值政策,只能产生更严重的财政不稳定性和政治上的敌对状态。这一问题又与协约国内部的贷款和战胜国(特别是法国)要求德国巨额赔款这些相互关联的难题交织在一起。所有的欧洲协约国都欠英国的债,也都少量地欠法国的债;然而这两个国家都大量地欠美国的债。由于布尔什维克拒绝偿还俄国的36亿美元巨额借款,由于美国要求收回贷款,由于法国、意大利和其他国家在得到德国的赔款之前拒绝还债,还由于德国人宣称他们不可能按要求支付那么多赔款,因而一连几年国际舞台一直陷入激烈争吵的状态。这就使西欧和怀有不满情绪的美国之间在政治上存在的鸿沟更加扩大了。

If it was true that these quarrels seemed smoothed over by the Dawes Plan of 1924, the political and social consequences of this turbulence had been immense, especially during the German hyperinflation of the previous year. What was equally alarming, although less well understood at the time, was that the apparent financial and commercial stabilization of the world economy by the mid-1920s rested on far more precarious foundations than had existed prior to the First World War. Although the gold standard was being restored in most countries by then, the subtle (and almost self-balancing) pre-1914 mechanism of international trade and monetary flows based upon the City of London had not. London had, in fact, made desperate attempts to recover that role—including the 1925 fixing of the sterling convertibility rate at the prewar level of £1:$4. 86, which badly hurt British exporters; and it also had resumed large-scale lending overseas. Nonetheless, the fact was that the center of world finance had naturally moved across the Atlantic between 1914 and 1919, as Europe’s international debts increased and the United States became the world’s greatest creditor nation. On the other hand, the quite different structure of the American economy—less dependent upon foreign commerce and much less integrated into the world economy, protectionist-inclined (especially in agriculture) rather than free-trading, lacking a full equivalent to the Bank of England, fluctuating much more wildly in its booms and busts, with politicians much more directly influenced by domestic lobbies—meant that the international financial and commercial system revolved around a volatile and flawed central point. There was now no real “lender of last resort,” offering longterm loans for the infrastructural development of the world economy and stabilizing the temporary disjunctions in the international accounts. 14

如果说1924年的道威斯计划似乎使这些争吵得到平息这一点是正确的话,那么这场混乱的政治和社会后果却是极为严重的,特别是在前一年[3]德国陷于极度通货膨胀期间更是如此。同样使人惊恐的是,20世纪20年代中期世界经济表面上的财政和商业稳定所依赖的基础,比第一次世界大战以前所存在的那种基础还要不稳定得多,尽管这一点在当时还不大为人知晓。虽然到这时金本位在大多数国家里得到了恢复,但是,以英国伦敦金融区为基础的、1914年以前的那种灵敏的(几乎是自我平衡的)国际贸易和金融流通机制已不复存在。事实上,伦敦为恢复这个角色曾做过不顾一切的努力,其中包括1925年把英镑的汇率固定在战前1英镑兑换4.86美元的水平上,这一行动使英国出口商遭受严重打击;英国还恢复了向海外大规模提供贷款的做法。然而事实是,在1914~1919年,当欧洲的国际债务日益增加而美国则变成了世界上最大的债权国之时,世界财政中心已经自然而然地跨过了大西洋。另一方面,美国经济的独特结构——较少依赖于对外贸易,很少与世界经济联为一体,倾向于保护主义(特别是在农业方面)而不是自由贸易,缺少一个与英格兰银行相同职能的对应机构,在繁荣与萧条之间大幅度地波动和政治家们更直接地受到本国的院外集团的影响等——意味着国际财政和商业体系在围绕着一个易变的和有缺陷的中心点运转。现在不再有真正的“最后可以求助的贷方”,来为发展世界经济基础设施和稳定国际账目结算中的暂时脱节现象提供长期贷款。

These structural inadequacies were concealed in the late 1920s, when vast amounts of dollars flowed out of the United States in short-term loans to European governments and municipalities, all willing to offer high interest rates in order to use such funds—not always wisely—both for development and to close the gap in their balance of payments. With short-term money being thus employed for longterm projects, with considerable amounts of investment (especially in central and eastern Europe) still going into agriculture and thus increasing the downward pressures on farm prices, with the costs of servicing these debts rising alarmingly and, since they could not be paid off by exports, being sustained only by further borrowings, the system was already breaking down in the summer of 1928, when the American domestic boom (and the Federal Reserve’s reactive increase in interest rates) sharply curtailed the outflow of capital.

这种结构上的不健全在20世纪20年代后期被掩盖起来了,那时巨额的美元以短期贷款的形式从美国流向欧洲各国政府和城市,所有人都愿意付出高额利息以利用这些资金——虽然并不总是明智的——来求得发展和弥补支付账款中的差额。短期贷款被用于长期计划,相当数目的投资(特别是在中欧和东欧)仍然被用于农业,因而日益增加农产品价格下跌的压力,支付这些债务利息的费用在令人惊恐地增加着,由于这些费用不能通过出口来偿付,所以只好用进一步的借款来维持,因此,到1928年夏天,这一体系已经崩溃了,那时美国的国内繁荣(和联邦储备局做出反应,提高了利率),导致了资本外流的大量缩减。

The ending of that boom in the “Wall Street crash” of October 1929 and the further reduction in American lending then instigated a chain reaction which appeared uncontrollable: the lack of ready credit reduced both investment and consumption; depressed demand among the industrialized countries hurt producers of foodstuffs and raw materials, who responded desperately by increasing supply and then witnessing the near-total collapse of prices—making it impossible for them in turn to purchase manufactured goods. Deflation, going off gold and devaluing the currency, restrictive measures on commerce and capital, and defaults upon international debts were the various expedients of the day; each one dealt a further blow to the global system of trade and credit. The archprotectionist Smoot-Hawley Tariff, passed (in the calculation of aiding American farmers) by the only country with a substantial trade surplus, made it even more difficult for other countries to earn dollars—and led to the inevitable reprisals, which devastated American exports. By the summer of 1932, industrial production in many countries was only half that of 1928, and world trade had shrunk by one-third. The value of European trade ($58 billion in 1928) was still down at $20. 8 billion in 1935—a decline which in turn hit shipping, shipbuilding, insurance, and so on. 15

1929年10月的那场繁荣在“华尔街崩溃”中结束,加之美国贷款的进一步减少,造成了无法控制的连锁反应:缺少足够的贷款既减少了投资,也减少了消费,使工业化国家降低了需求,打击了粮食和原材料的生产者,而它们的反应就是拼命地增加供应,然后目睹价格体系几乎全部崩溃,这反过来又使它们不能购买工业制品。紧缩通货、出卖黄金和贬值货币、对商业和资本采取限制性措施以及拖欠国际债务,都成了那个时代各种各样的权宜之计;而每一个权宜之计,又都使全球的贸易和信用体系遭到进一步的打击。典型的保护主义的《斯姆特-霍利关税法》(为了帮助美国农民)在一个唯一拥有巨额贸易盈余的国家里被通过,使其他国家赚取美元变得愈加困难,这就遭到别国不可避免的报复,从而破坏了美国的商品出口。到1932年夏天,许多国家的工业产量只及1928年产量的一半,世界贸易减少了1/3。欧洲贸易额(1928年为580亿美元)到1935年下降到208亿美元,这一下降反过来又打击了海运、造船和保险等行业。

Given the severity of this worldwide depression and the massive unemployment caused by it, there was no way international politics could escape from its dire effects. The fierce competition in manufactures, raw materials, and farm produce increased national resentments and impelled many a politician, aware of his constituents’ discontents, into trying to make the foreigner pay; more extreme groups, especially of the right, took advantage of the economic dislocation to attack the entire liberal-capitalist system and to call for assertive “national” policies, backed if necessary by the sword. The more fragile democracies, in Weimar Germany especially but also in Spain, Rumania, and elsewhere, buckled under these politico-economic strains. The cautious conservatives who ruled Japan were edged out by nationalists and militarists. If the democracies of the West weathered these storms better, their statesmen were forced to concentrate upon domestic economic management, increasingly tinged with a beggar-thy-neighbor attitude. Neither the United States nor France, the main gold-surplus countries, were willing to bail out debtor states; indeed, France inclined more and more to use its financial strength to try to control German behavior (which merely intensified resentments on the other side of the Rhine) and to aid its own European diplomacy. Similarly, the “Hoover moratorium” on German reparations, which so infuriated the French, could not be separated from the issue of reductions in (and ultimately defaults on) war debts, which made the Americans bitter. Competitive devaluations in currency, and disagreements at the 1933 World Economic Conference about the dollar-sterling rate, completed this gloomy picture.

鉴于这场世界性危机及其引起的大规模失业现象极其严重,国际政治是无法逃脱这场危机所带来的灾难性影响的。制造业、原材料和农产品等方面的激烈竞争,增加了国家间的怨恨,迫使许多政治家们意识到选民们的不满,从而力图叫外国人多掏腰包。一些比较极端的集团,特别是右翼集团,利用经济混乱之机攻击整个自由资本主义制度,并要求实行以武力为后盾的(如果需要的话)专断的“国家”政策。一些比较脆弱的民主国家,特别是魏玛德国,当然还有西班牙、罗马尼亚和其他国家,在这些政治一经济压力下屈服了。统治日本的谨小慎微的保守主义者被民族主义者和军阀主义者挤掉了。西方民主国家如要平安地度过这些暴风雨,其政治家们就不得不集中力量加强对国内经济的管理,并抱着使四邻日益贫困这样一种态度。美国和法国这两个主要的黄金剩余国都不愿意帮助债务国摆脱困境。确实,法国越来越倾向于使用它的财政力量来控制德国的行为(这只能加剧莱茵河彼岸的怨恨)和加强它自己的欧洲外交。与此相类似的是,关于德国赔款的“胡佛延期付款法”与减少战争赔款(最终是不还债)问题的提出,是密不可分的,前者大大地激怒了法国,而后者则使美国大受其苦。货币的竞相贬值和1933年世界经济会议上关于美元和英镑汇率的分歧,在人们面前呈现出一幅暗淡的图景。

By that time, the cosmopolitan world order had dissolved into various rivaling subunits: a sterling block, based upon British trade patterns and enhanced by the “imperial preferences” of the 1932 Ottawa Conference: a gold block, led by France; a yen block, dependent upon Japan, in the Far East; a U. S. -led dollar block (after Roosevelt also went off gold); and, completely detached from these convulsions, a USSR steadily building “socialism in one country. ” The trend toward autarky was thus already strongly developed even before Adolf Hitler commenced his program of creating a self-sufficient, thousand-year Reich in which foreign trade was reduced to special deals and “barter” agreements. With France having repeatedly opposed the Anglo-Saxon powers over the treatment of German reparations, with Roosevelt claiming that the United States always lost out in deals with the British, and with Neville Chamberlain already convinced of his later remark that the American policy was all “words,”16 the democracies were in no frame of mind to cooperate in handling the pressures building up for territorial charges in the flawed 1919 world order.

那时候,整个世界秩序已经瓦解成各种相互竞争的小单位:以英国贸易模式为基础,并为1932年渥太华会议确定的“帝国特惠制”所加强的英镑区;以法国为首的金本位区;以日本为依靠的远东日元区;以美国为首的美元区(罗斯福以后也出售黄金);以及远离这些动荡不安地区,并在“一国之内稳定地建设社会主义”的苏联。甚至在阿道夫·希特勒宣布要建立一个自给自足的千年帝国计划之前,德国的自给自足政策就已经得到了很大的发展,在他要建立的千年帝国中,对外贸易变成特殊交易和“物品交换”协定。由于法国不断地反对盎格鲁-撒克逊人在处理德国赔款问题上的权力,由于罗斯福宣称美国在同英国人打交道时总是失败,又由于张伯伦在他前不久的讲话中已经确信美国的政策都是“空话”,所以民主国家在混乱的1919年世界秩序中无心合作去处理领土诉讼所造成的压力。

The Old World statesmen and foreign offices had always found it difficult either to understand or to deal with economic issues; but perhaps an even more disruptive feature, to those fondly looking back at the cabinet diplomacy of the nineteenth century, was the increasing influence of mass public opinion upon international affairs during the 1920s and 1930s. In some ways, of course, this was inevitable. Even before the First World War, political groups across Europe had been criticizing the arcane, secretive methods and elitist preconceptions of the “old diplomacy,” and calling instead for a reformed system, where the affairs of state were open to the scrutiny of the people and their representatives. 17 These demands were greatly boosted by the 1914–1918 conflict, partly because the leaderships who demanded the total mobilization of society realized that society, in turn, would require compensations for its sacrifices and a say in the peace; partly because the war, fondly proclaimed by Allied propagandists as a struggle for democracy and national self-determination, did indeed smash the autocratic empires of east-central Europe; and partly because the powerful and appealing figure of Woodrow Wilson kept up the pressures for a new and enlightened world order even as Clemenceau and Lloyd George were proclaiming the need for total victory. 18

旧世界的政治家和外交部门总是认为理解和处理经济问题是很困难的。而对那些乐于回顾19世纪密室外交的人们来说,20世纪20年代和30年代期间民众舆论对于国际事务的影响日益增加也许更具有破坏性。从某些方面来说,这种情况无疑是不可避免的。甚至在第一次世界大战以前,整个欧洲的各政治集团就在不断地批评“旧式外交”的神秘性、秘密方法以及头面人物的先入之见,并要求用一种革新的体制取而代之。在这种新体制中,国家事务接受人民及其代表的监督。这些要求由于1914~1918年的冲突而变得更加强烈,其部分原因是,要求社会总动员的领导者们认识到,社会反过来也会要求对它做出的牺牲给予补偿,并在和平时期拥有发言权;另一部分原因是,被协约国宣传机构称之为为民主和民族自决权而战的这场战争,确实摧毁了中欧东部的专制帝国;还有部分原因是,甚至当克里孟梭和劳埃德·乔治正在叫嚣需要彻底的胜利之时,伍德罗·威尔逊这位有权势有感染力的人物仍不断施加压力,坚持要建立一个新的开明的世界秩序。

But the problem with “public opinion” after 1919 was that many sections of it did not match that fond Gladstonian and Wilsonian vision of a liberal, educated, fairminded populace, imbued with internationalist ideas, utilitarian assumptions, and respect for the rule of law. As Arno Mayer has shown, “the old diplomacy” which (it was widely claimed) had caused the World War was being challenged after 1917 not only by Wilsonian reformism, but also by the Bolsheviks’ much more systematic criticism of the existing order—a criticism of considerable attraction to the organized working classes in both belligerent camps. 19 While this caused nimble politicians such as Lloyd George to invent their own “package” of progressive domestic and foreign policies, to neutralize Wilson’s appeal and to check labor’s drift toward socialism,20 the impact upon more conservative and nationalist figures in the Allied camp was quite different. In their view, Wilsonian principles must be firmly rejected in the interests of national “security,” which could only be measured in the hard cash of border adjustments, colonial acquisitions, and reparations; while Lenin’s threat, which was much more frightening, had to be ruthlessly smashed, in its Bolshevik heartland and (especially) in the imitative soviets which sprang up in the West. The politics and diplomacy of the peacemaking,21 in other words, was charged with background ideological and domestic-political elements to a degree unknown at the congresses of 1856 and 1878.

但是1919年以后,“民众舆论”存在的问题是,它在许多方面确实与格莱斯顿和威尔逊天真的幻想不相符。他们的幻想认为,民众是宽宏大度的,有教养的,公正的,富有国际主义思想和功利主义设想,并尊重法治。正如阿尔诺·迈耶所指出的,导致世界大战的“旧式外交”(这一点已得到普遍承认)在1917年以后不仅受到威尔逊改良主义的挑战,而且也受到布尔什维克对现存秩序更为有系统的批评的挑战,这种批评对于两大参战国阵营中有组织的工人阶级都具有相当大的吸引力。这就使得像劳埃德·乔治这样聪明的政治家们要设法把他们自己进步的对内对外政策加以装潢打扮,以抵消威尔逊的号召力,并制止劳工向往社会主义的倾向。但这种情况对于协约国阵营中那些更为保守的和民族主义的人物的影响却完全不同。在他们看来,为了国家的“安全”,必须坚定地反对威尔逊原则,而国家的“安全”只能通过边界的调整、殖民地的取得和赔款这些硬通货来衡量。同时对于更为令人惊恐的苏联威胁,则必须无情地予以摧毁,这种威胁既存在于布尔什维克的心脏地带,(尤其是)又存在于在西方崛起的仿效的苏维埃中。换句话说,调停争端的政治和外交受到历史背景、意识形态和国内政治因素的制约,其程度是1856年和1878年的国际会议所想象不到的。

There was more. In the western democracies, the images of the First World War which prevailed by the late 1920s were of death, destruction, horror, waste, and the futility of it all. The “Carthaginian peace” of 1919, the lack of those benefits promised by wartime politicians in return for the people’s sacrifices, the millions of maimed veterans and of war widows, the economic troubles of the 1920s, the loss of faith and the breakdown in Victorian social and personal relationships, were all blamed upon the folly of the July 1914 decisions. 22 But this widespread public recoil from fighting and militarism, mingled in many quarters with the hope that the League of Nations would render impossible any repetition of that disaster, was not shared by all of the war’s participants—even if Anglo-American literature gives that impression. 23 To hundreds of thousands of former Frontsoldaten across the continent of Europe, disillusioned by the unemployment and inflation and boredom of the postwar bourgeois-dominated order, the conflict had represented something searing but positive: martial values, the camaraderie of warriors, the thrill of violence and action. To such groups, especially in the defeated nations of Germany and Hungary and in the bitterly dissatisfied victor nation of Italy, but also among the French right, the ideas of the new fascist movements—of order, discipline, and national glory, of the smashing of the Jews, Bolsheviks, intellectual decadents, and self-satisfied liberal middle classes—had great appeal. In their eyes (and in the eyes of their equivalents in Japan), it was struggle and force and heroism which were the enduring features of life, and the tenets of Wilsonian internationism which were false and outdated. 24

不仅如此,到20世纪20年代后期,在西方民主国家里,人们对第一次世界大战的普遍看法是死亡、破坏、恐怖、浪费和毫无意义。1919年“迦太基式的和平”到来后,战时政治家们对人民付出的牺牲要给予报偿的诺言没有兑现,数百万残废退伍军人和数百万战争寡妇的出现,20世纪20年代后期的经济困难,信仰的丧失以及维多利亚式的社会关系和私人情感的崩溃等,所有这些都要归罪于1914年7月那些愚蠢的决定。民众中战斗精神和尚武精神的普遍减退,在许多方面是与认为国际联盟会使那种灾难不再重现的良好愿望结合在一起的,但是,这种战斗精神的减退,并不是所有战争参加者人人都有的——尽管英美文学曾给人们造成了这种印象。对于那些曾横跨过欧洲大陆赴前线作战的成千上万的士兵来说(失业、通货膨胀和对于战后资产阶级统治秩序的厌倦使他们的幻想破灭了),那场战争虽然冷酷无情,但也有某些积极的东西,例如军人的价值、战友情谊和暴力行动的刺激性等。对于战败国德国和匈牙利以及最令人不满的战胜国意大利等国的某些集团和法国的右翼派别来说,新法西斯运动的思想——即要求建立秩序、纪律和国家荣誉的思想,消灭犹太人、布尔什维克、颓废派知识分子和自满的自由中产阶级的思想——具有极大的吸引力。在他们的眼中(和在日本他们的同类人眼中),只有斗争、力量和英雄主义才是生活的永久特征,威尔逊国际主义的原则是虚假的和过时的。

What this meant was that international relations during the 1920s and 1930s continued to be complicated by ideology, and by the steady fissuring of world society into political blocs which only partly overlapped with the economic subdivisions mentioned earlier. On the one hand, there were the western democracies, especially in the English-speaking world, recoiling from the horror of the First World War, concentrating upon domestic (especially socioeconomic) issues, and massively reducing their defense establishments; and while the French leadership kept up a large army and air force out of fear of a revived Germany, it was evident that much of its public shared this hatred of war and desire for social reconstruction. On the other hand, there was the Soviet Union, isolated in so many ways from the global politico-economic system yet attracting admirers in the West because it offered, purportedly, a “new civilization” which inter alia escaped the Great Depression,25 though the USSR was also widely detested. Finally, there were, at least by the 1930s, the fascistic “revisionist” states of Germany, Japan, and Italy, which were not only virulently anti-Bolshevik but also denounced the liberalcapitalist status quo that had been reestablished in 1919. All this made the conduct of foreign policy inordinately difficult for democratic statesmen, who possessed little grasp of either the fascist or the Bolshevik frame of mind, and yearned merely to return to that state of Edwardian “normalcy” which the war had so badly destroyed.

这意味着20世纪20年代和30年代期间的国际关系,仍继续被意识形态和国际社会这两大因素困扰着,并牢固地分裂成若干政治集团,其中部分政治集团的划分与上述的经济区的划分是一致的。一方面,西方民主国家,特别是英语世界,被第一次世界大战的恐怖所吓退,正集中力量处理国内问题,特别是社会经济问题,并大规模地削减它们的国防建设投资;然而,法国领导者由于害怕德国的复活而继续保持着一支庞大的陆军和空军。很明显,许多法国公众也痛恨战争并渴望社会重建。在另一方面,苏联虽然在许多方面孤立于全球政治—经济体系之外,但是对于西方的崇拜者来说仍具有吸引力,因为它提供了一种“新文明”,尽管这种“新文明”是令人怀疑的。只有苏联避免了大萧条,尽管它也受到普遍的憎恨。最后,至少到20世纪30年代,已有德国、日本和意大利成了法西斯的“修正主义”国家,它们不仅恶毒地反对布尔什维克,而且也谴责1919年重建起来的自由资本主义现状。所有这一切,使得民主国家的政治家们履行外交政策极端困难,他们对于法西斯主义者或是布尔什维克的意图都掌握不住,因而只有渴望回到那种已遭到战争严重破坏的爱德华七世时期的“常规”状态。

Compared with these problems, the post-1919 challenges to the Eurocentric world which were beginning to arise in the tropics were less threatening—but still important. Here, too, one can detect precedents prior to 1914, such as Arabi Pasha’s revolt in Egypt, the young Turks’ breakthrough after 1908, Tilak’s attempts to radicalize the Indian Congress movement, and Sun Yat-sen’s campaign against western dominance in China; by the same token, historians have noted how events such as the Japanese defeat of Russia in 1905 and the abortive Russian revolution of that same year fascinated and electrified proto-nationalist forces elsewhere in Asia and the Middle East. 26 Ironically, yet predictably, the more that colonialism penetrated underdeveloped societies, drew them into a global network of trade and finance, and brought them into contact with western ideas, the more this provoked an indigenous reaction; whether it came in the form of tribal unrest against restrictions upon their traditional patterns of life and trade or, more significantly, in the form of western-educated lawyers and intellectuals seeking to create mass parties and campaigning for national self-determination, the result was an increasing challenge to European colonial controls.

如与上述这些问题相比,1919年以后在热带地区开始发生的一些问题,对于以欧洲为中心的这个世界的威胁性要小一些,但仍然是很重要的。在这里,人们也能发现1914年以前发生的一些事件,如埃及的阿拉比·帕夏起义,1908年以后青年土耳其党人的暴动,印度的提拉克企图使国大党更为激进的运动,以及中国孙中山反对西方统治的行动。由于同样原因,历史学家们注意到像日本在1905年打败俄国和同一年俄国发生的流产革命这样的事件,对于亚洲和中东其他地区典型的民族主义势力具有强烈的吸引力,并使其从中受到了鼓舞。具有讽刺意味然而又是可以预见的是,殖民主义越是渗透进不发达社会,把它们拉进全球商业和金融网络并使它们接触西方思想,就越容易激起本地人的反抗,来反对对他们传统的生活和贸易方式进行限制。不论这种反抗是以部落暴乱的形式出现,还是以受过西方教育的律师和知识分子寻求创立民众党派和发起民族自决运动这种更有意义的形式出现,其结果都是对欧洲殖民统治的一种日益增强的挑战。

The First World War accelerated these trends in all sorts of ways. In the first place, the intensified economic exploitation of the raw materials in the tropics and the attempts to make the colonies contribute—both with manpower and with taxes —to the metropolitan powers’ war effort inevitably caused questions to be asked about “compensation,” just as it was doing among the working classes of Europe. 27 Furthermore, the campaigning in West, Southwest, and East Africa, in the Near East, and in the Pacific raised questions about the viability and permanence of colonial empires in general—a tendency reinforced by Allied propaganda about “national self-determination” and “democracy,” and German counterpropaganda activities toward the Maghreb, Ireland, Egypt, and India. By 1919, while the European powers were establishing their League of Nations mandates—hiding their imperial interests behind ever more elaborate fig leaves, as A. J. P. Taylor once described it—the Pan African Congress had been meeting in Paris to put its point of view, the Wafd Party was being founded in Egypt, the May Fourth Movement was active in China, Kemal Ataturk was emerging as the founder of modern Turkey, the Destour party was reformulating its tactics in Tunisia, the Sarehat Islam had reached a membership of 2. 5 million in Indonesia, and Gandhi was catalyzing the many different strands of opposition to British rule in India. 28

第一次世界大战在各方面都加速了这些倾向的发展。首先,对于热带地区原材料经济剥削的加剧,和使殖民地为宗主国的战争努力做出人力和税收的贡献的企图,都不可避免地会引起殖民地人民提出“补偿”的问题,就像欧洲的工人阶级正在做的那样。其次,西非、西南非和东非、近东以及太平洋地区的反对殖民地运动,从总体上对殖民帝国的生存能力和永久性提出了疑问。这种倾向由于协约国关于“民族自决”和“民主”的宣传以及德国对于马格里布、爱尔兰、埃及和印度进行的反宣传活动而发展得更快。到1919年,正当欧洲列强建立它们的国际联盟委任统治权时——如A·J·P·泰勒所描述的,这是用精心制作的遮羞布来掩藏它们的帝国主义利益——泛非大会在巴黎召开并提出了自己的主张,华夫脱党在埃及建立起来,中国的五四运动风起云涌,凯末尔·阿塔图尔克作为现代土耳其的创立者正在崛起,突尼斯宪政党正在重新制定它的策略,印度尼西亚的伊斯兰教联盟成员已发展到250万人,而甘地则正在推动各种力量反对英国人统治印度。

More important still, this “revolt against the West” would no longer find the Great Powers united in the supposition that whatever their own differences, a great gulf lay between themselves and the less-developed peoples of the globe; this, too, was another large difference from the time of the Berlin West Africa Conference. Such unity had already been made redundant by the entry into the Great Power club of the Japanese, some of whose thinkers were beginning to articulate notions of an East Asian “co-prosperity sphere” as early as 1919. 29 And it was overtaken altogether by the coming of the two versions of the “new diplomacy” proposed by Lenin and Wilson—for whatever the political differences between those charismatic leaders, they had in common a dislike of the old European colonial order and a desire to transform it into something else. Neither of them, for a variety of reasons, could prevent the further extension of that colonial order under the League mandates; but their rhetoric and influence seeped across imperial demarcation zones and interacted with the mobilization of indigenous nationalists. This was evident in China by the late 1920s, where the old European order of treaty privileges, commercial penetration, and occasional gunboat actions was beginning to lose ground to competing alternative “orders” proposed by Russia, the United States, and Japan, and to wilt in the face of the resurgent Chinese nationalism. 30

更加重要的是,这次“反叛西方”的运动发现,那种大国之间不论有着怎样的分歧仍能团结起来进行讨伐的时代已一去不复返了,那时在这些大国和世界上不发达民族之间有着一道巨大的鸿沟。这一点与在柏林召开西非会议时的情况也大不相同。那种团结已经由于日本加入大国俱乐部而变得多余。早在1919年,日本的一些思想家就开始明确阐述“东亚共荣圈”的见解。而且这种团结被列宁和威尔逊提出的“新外交”的两种说法所摧毁,不管这两位得到群众狂热拥护的领袖之间在政治上有着怎样的差异,他们都不喜欢旧的欧洲殖民秩序并想要用别的东西取而代之。由于种种原因,在国际联盟委任统治权存在的情况下,他们俩都不能阻止那种旧殖民秩序的进一步扩展;但是他们的雄辩言辞和影响已在帝国的统治区内广泛传播,并与本地民族主义者的动员相互影响。这在20世纪20年代后期的中国表现得尤为明显,在那里,条约特权、商业渗透和偶尔的炮舰行动这一类旧式欧洲秩序,在与苏联、美国和日本提供的可以选择的“秩序”的竞争中开始退却,并在复活的中华民族主义面前畏缩不前。

This did not mean that western colonialism was about to collapse. The sharp British response at Amritsar in 1919, the Dutch imprisonment of Sukarno and other Indonesian nationalist leaders and breaking-up of the trade unions in the late 1920s, the firm French reaction to Tonkinese unrest at the intense agricultural development of rice and rubber, all testified to the residual power of European armies and weaponry. 31 And the same could be said, of course, of Italy’s belated imperial thrust into Abyssinia in the mid-1930s. Only the far larger shocks administered by the Second World War would really loosen these imperial controls. Nevertheless, this colonial unrest was of some importance to international relations in the 1920s and especially in the 1930s. First of all, it distracted the attention (and the resources) of certain of the Great Powers from their concern with the European balance of power. This was preeminently the case with Britain, whose leaders worried far more about Palestine, India, and Singapore than about the Sudetenland or Danzig—such priorities being reflected in their post-1919 “imperial” defense policy;32 but involvements in Africa also affected France to the same degree, and of course quite distracted the Italian military. Furthermore, in certain instances the reemer-gence of extra-European and colonial issues was cutting right across the former 1914–1918 alliance structure. Not only did the question of imperialism cause Americans to be ever more distrustful of Anglo-French policies, but events such as the Italian invasion of Abyssinia and the Japanese aggression into mainland China divided Rome and Tokyo from London and Paris by the 1930s—and offered possible partners to German revisionists. Here again, international affairs had become that bit more difficult to manage according to the prescriptions of the “old diplomacy. ”

这并不意味着西方殖民主义就要走向崩溃。1919年,英国在阿姆利则的强烈反应,20世纪20年代后期荷兰监禁苏加诺和其他印度尼西亚民族主义领导人解散工会的行为,以及法国对由于水稻和橡胶的迅猛发展而导致的东京(越南)骚动所采取的强硬立场,所有这些都证明了欧洲军队和武器的残余力量仍很强大。毫无疑问,20世纪30年代中期,意大利帝国对于阿比西尼亚(今埃塞俄比亚)的入侵也同样可以这样讲。只有第二次世界大战所造成的规模巨大的震荡才能够真正地使这些帝国放松控制。然而,殖民地的这种骚动对于20世纪20年代,特别是20世纪30年代的国际关系还是有些重要性的。首先,它分散了某些大国的一些注意力(和资源),使它们不能全力关注欧洲的均势。英国就是很明显的例子,英国领导人更加担心的是巴勒斯坦、印度和新加坡,而不是苏台德或但泽(今格但斯克),这些优先考虑反映在他们1919年以后的“帝国”防御政策中;而对非洲的干预也在同等程度上影响了法国,当然也在相当程度上分散了意大利的军事力量。其次,在某些情况下,欧洲以外的问题和殖民地问题的再度出现正在分解着1914~1918年的联盟结构。不仅仅是帝国主义的问题使美国人对英法的政策更加不信任,而且20世纪30年代像意大利入侵阿比西尼亚和日本侵略中国这样的事件,也使罗马和东京同伦敦和巴黎分道扬镳,从而为德国修正主义者提供了可能的伙伴。在这里,根据“旧式外交”的惯例,国际事务又一次变得更加难以处理了。

The final major cause of postwar instability was the awkward fact that the “German question” had not been settled, but made more intractable and intense. The swift collapse of Germany in October 1918 when its armies still controlled Europe from Belgium to the Ukraine came as a great shock to nationalist, right-wing forces, who tended to blame “traitors within” for the humiliating surrender. When the terms of the Paris settlement brought even more humiliations, vast numbers of Germans denounced both the “slave treaty” and the Weimar-democratic politicians who had agreed to such terms. The reparations issue, and the related hyperinflation of 1923, filled the cup of German discontents. Very few were as extreme as the National Socialists, who appeared as a cranky demagogic fringe movement for much of the 1920s; but very few Germans were not revisionists, in one form or another. Reparations, the Polish corridor, restrictions on the armed forces, the separation of German-speaking regions from the Fatherland were not going to be tolerated forever. The only questions were how soon these restrictions could be abolished and to what extent diplomacy should be preferred to force in order to alter the status quo. In this respect, Hitler’s coming to power in 1933 merely intensified the German drive for revisionism. 33

战后不稳定的最后一个主要原因是存在着这样一个棘手的事实,即“德国问题”不仅一直没有得到解决,反而变得更加难以处理和更加紧张了。1918年10月,当德军仍控制着从比利时到乌克兰的大半个欧洲的时候,德国却迅速地崩溃了。这对民族主义者和右翼势力是一次巨大的打击,他们为了可耻的投降而一直在谴责“内部叛徒”。当巴黎和约条款带来了更多的耻辱时,大多数德国人都纷纷对这一“奴役性条约”和同意这些条款的魏玛民主政治家们进行谴责。赔款问题以及与之相关的1923年的极其严重的通货膨胀,更使德国人的不满达到了极点。在德国,像国家社会主义党党徒这样的极端分子还是少数,他们在20年代大部分时间内,以一种疯狂的、蛊惑人心的、偏激的运动形式出现在社会上。而绝大多数德国人都是修正主义者,只是表现形式不同而已。赔款、波兰走廊、对武装部队的限制以及把讲德语的地区从祖国划分出去等做法,是不会被永远忍受下去的。问题只是这些限制多久才能被废除,以及为了改变现状,应该在多大程度上宁愿用武力而不用外交来解决问题。在这方面,可以说1933年希特勒上台仅仅是加速了德国走向修正主义的进度。

The problem of settling Germany’s “proper” place in Europe was compounded by the curious and unbalanced distribution of international power after the First World War. Despite its territorial losses, military restrictions, and economic instability, Germany after 1919 was still potentially an immensely strong Great Power. A more detailed analysis of its strengths and weaknesses will be given below, but it is worth noting here that Germany still possessed a much larger population than France and an iron-and-steel capacity which was around three times as big. Its internal communications network was intact, as were its chemical and electrical plants and its universities and technical institutes. “At the moment in 1919, Germany was down-and-out. The immediate problem was German weakness; but given a few years of ‘normal’ life, it would again become the problem of German strength. ”34

安排德国在欧洲的“恰当”地位的问题,与第一次世界大战以后国际权力分配奇特的不平衡交织在一起。尽管德国存在着领土丧失、军事上受限制和经济上不稳定等因素,但是,1919年以后的德国,从潜力上来说,仍然是一个强大的大国。在后面的章节里,我们将会对它的强势和弱点进行更详尽的分析,而在这里值得注意的是,德国仍然拥有比法国多得多的人口,它的钢铁生产能力大约是法国的3倍。德国的化工厂和电气工厂以及大学和技术学院都同国内交通网络一样,丝毫没有受到损害。“在1919年那个时刻,德国是被打垮了。直接的问题是德国的软弱。但是经过几年的‘正常’生活以后,它将再一次提出德国的强大问题。”

Furthermore, as Taylor points out, the old balance of power on the European continent which had helped to restrain German expansionism was no more. “Russia had withdrawn; Austria-Hungary had vanished. Only France and Italy remained, both inferior in manpower and still more in economic resources, both exhausted by the war. ”35 And, as time went on, first the United States and then Britain showed an increasing distaste for interventions in Europe, and an increasing disapproval of French efforts to keep Germany down. Yet it was precisely this apprehension that France was not secure which drove Paris into seeking to prevent a revival of German power by all means possible: insisting on the full payment of reparations; maintaining its own large and costly armed forces; endeavoring to turn the League of Nations into an organization dedicated to preserving the status quo; and resisting all suggestions that Germany be admitted to “arm up” to France’s level36—all of which, predictably, fueled German resentments and helped the agitations of the right-wing extremists.

此外,正如泰勒所指出的,有助于限制德国扩张主义的旧的欧洲均势已不复存在。“俄国退却了,奥匈帝国消失了。剩下的只有法国和意大利,这两个国家在人力上处于劣势,在经济资源上更处于劣势,并且都被战争拖得精疲力竭。”随着时间的推移,先是美国,然后是英国,对于在欧洲进行干预越来越表现出一种厌恶感,并且越来越不赞成法国控制德国的努力。然而确切地说,正是法国的这种不安全感促使巴黎想尽一切办法来防止德国力量的复活;这些办法包括:坚持全部偿还赔款,维持它自己的规模庞大而又代价高昂的武装部队,力图使国际联盟变成一个专门维持现状的组织,反对允许德国按照法国的水平“武装起来”的一切建议。可以预料,所有这些都进一步激起了德国的不满情绪并有助于右翼极端分子进行煽动。

The other device in France’s battery of diplomatic and political weapons was its link with the eastern European “successor states. ” On the face of it, support for Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the other beneficiaries of the 1919–1921 settlements in that region was both a plausible and a promising strategy;37 by it, German expansionism would be checked on each flank. In reality, the scheme was fraught with difficulties. Because of the geographical dispersion of the various populations under the former multinational empires, it had not been possible in 1919 to create a territorial settlement which was ethnically coherent; large groups of minorities therefore lived on the wrong side of every state’s borders, offering a source not only of internal weakness but also of foreign resentments. In other words, Germany was not alone in desiring a revision of the Paris treaties; and even if France was eager to insist upon no changes in the status quo, it was aware that neither Britain nor the United States felt any great commitment to the hastily arranged and irregular boundaries in this region. As London made clear in 1925, there would be no Locarno-type guarantees in eastern Europe. 38

在法国一整套外交和政治武器中的另一个策略就是,它与东欧“继承人国家”的联系。从表面上看,支持波兰、捷克斯洛伐克和那个地区1919~1921年各项和约的受益者,既是一种花言巧语的战略,同时又是一种有希望的战略:这样做就可以在各个侧翼抑制德国扩张主义。实际上,这个计划充满了困难,因为这个地区在以前多民族帝国的统治下,在地理上是各种民族散居的区域,而且1919年时各民族间不可能团结一致地来解决领土问题,因此,在每一个国家的边界之外都居住有大群的少数民族,这不仅是产生国内弱点的根源,也是产生外国人不满的根源。换句话说,在希望对巴黎和约进行修正方面,德国并不是孤立的。即使法国迫切要求维持现状,但无论英国或美国,都不认为自己对这一地区仓促安排的、不规则的边界负有多大义务。正如伦敦在1925年所澄清的,在东欧并不存在洛迦诺式的保证。

The economic scene in eastern and central Europe made matters even worse, since the erection of customs and tariff barriers around these newly created countries increased regional rivalries and hindered general development. There were now twenty-seven separate currencies in Europe instead of fourteen as before the war, and an extra 12,500 miles of frontiers; many of the borders separated factories from their raw materials, ironworks from their coalfields, farms from their market. What was more, although French and British bankers and enterprises moved into these successor states after 1919, a much more “natural” trading partner for those nations was Germany, once it had recovered its own economic stability in the 1930s. Not only was it closer to, and better connected by road and rail with, the eastern European market, but it could readily absorb the area’s agricultural surpluses in the way that farm-surplus France and imperial-preference Britain could not, offering in return for Hungarian wheat and Rumanian oil much-needed machinery and (later) armaments. Moreover, these countries, like Germany itself, had currency problems and thus found it easier to trade on a “barter” basis. Economically, therefore, Mitteleuropa could again steadily become a Germandominated zone. 39

由于这些新建国家建立了海关和关税壁垒,从而增加了地区竞争并阻碍了全面发展,因而东欧和中欧的经济情况更加恶化。在欧洲,战前独立的货币共有14种,现在却增加到27种;新增加的边境线有1.25万英里;许多边界都使工厂同原材料、钢铁厂同煤田以及农场同市场分离开了。更有甚者,尽管在1919年以后英国和法国的银行家和企业进入了这些继承人国家,但是一旦德国在20世纪30年代能够恢复自己的经济稳定,那么,德国才是这些国家的更加“天然”的贸易伙伴。德国不仅在地理位置上更靠近这些国家,有公路和铁路与东欧市场密切联系,而且它还能够很容易地吸收这一地区的剩余农产品,用这些国家所急需的机械和(后来)军事装备同匈牙利的小麦和罗马尼亚的石油进行交换,而农产品剩余的法国和实行帝国特惠制的英国却做不到这一点。另外,这些国家也和德国一样,都存在着通货问题,于是它们发现进行“换货”贸易更简便易行。因此,从经济角度来看,中欧可以再次稳固地成为德国控制区。

Many of the participants at the Paris negotiations of 1919 were aware of some (though obviously not all) of the problems mentioned above. However, they felt that, like Lloyd George, they could look to the newly created League of Nations “to remedy, to repair, and to redress [It] will be there as a Court of Appeal to readjust crudities, irregularities, injustices. ”40 Surely any outstanding political or economic quarrel between states could now be settled by reasonable men meeting around a table in Geneva. That again seemed a plausible supposition to make in 1919, but it was to founder on hard reality. The United States would not join the League. The Soviet Union was treated as a pariah state and kept out of the League. So, too, were the defeated powers, at least for the first few years. When the revisionist states commenced their aggressions in the 1930s, they soon thereafter left the League.

1919年巴黎会议的许多参加者已经意识到了上述问题中的某些问题(显然不是全部)。但是,他们像劳埃德·乔治一样,认为可以指望新建的国际联盟“去医治、修补和纠正……(它)将会作为一个上诉法庭去对残暴的、不道德的和不公正的行为进行重新调节”。国家间任何悬而未决的政治和经济争端,现在都可以由通情达理的人们在日内瓦聚在一张桌子周围加以解决。上述设想在1919年来说似乎是合理的,但是它在残酷的现实面前遭到失败。美国并没有加入国际联盟。苏联被作为国际社会的弃儿来对待,并被排除在国际联盟之外。战败国的遭遇也是如此,至少在开始几年是这样。当20世纪30年代修正主义国家开始侵略行动时,它们很快就退出了国际联盟。

Furthermore, because of the earlier disagreements between the French and British versions of what the League should be—a policeman or a conciliator—the body lacked enforcement powers and had no real machinery of collective security. Ironically, therefore, the League’s actual contribution turned out to be not deterring aggressors, but confusing the democracies. It was immensely popular with warwearied public opinion in the West, but its very creation then permitted many the argument that there was no need for national defense forces since the League would somehow prevent future wars. In consequence, the existence of the League caused cabinets and foreign ministers to wobble between the “old” and the “new” diplomacy, usually securing the benefits of neither, as the Manchurian and Abyssinian cases amply demonstrated.

另外,由于英国和法国早期对于国际联盟该是一个什么样的机构——是一个警察,还是一个调停者——有分歧,这就使得这一组织缺乏强制执行的权力,也没有真正的集体安全机制。因此,令人啼笑皆非的是,事实证明国际联盟的实际贡献不是遏制侵略者,而是使民主国家陷入混乱状态。在西方,厌战舆论极为盛行,但是这一舆论的发源地这时却允许许多这样的论调存在,即国防力量的存在已无必要,因为国际联盟将会以某种方式防止未来的战争。因此,国际联盟的存在使得内阁和外交大臣们在“旧式”外交和“新式”外交之间摇来摆去,结果通常是哪一种外交的好处也没得到,九一八事变和阿比西尼亚事件充分说明了这一点。

In the light of all of the above difficulties, and of the overwhelming fact that Europe plunged into another great war only twenty years after signing the Treaty of Versailles, it is scarcely surprising that historians have seen this period as a “twenty years’ truce” and portrayed it as a gloomy and fractured time—full of crises, deceits, brutalities, dishonor. But With book titles like A Broken World, The Lost Peace, and The Twenty Years’ Crisis describing these entire two decades,41 there is a danger that the great differences between the 1920s and the 1930s may be ignored. To repeat a remark made earlier, by the late 1920s, the Locarno and Kellogg-Briand (Pact of Paris) treaties, the settling of many Franco-German differences, the meetings of the League, and the general revival of prosperity seemed to indicate that the First World War was at last over as far as international relations were concerned. Within another year or two, however, the devastating financial and industrial collapse had shaken that harmony and had begun to interact with the challenges which the Japanese and German (and later Italian) nationalists would pose to the existing order. In a remarkably short space of time, the clouds of war returned. The system was under threat, in a fundamental way, just at a moment when the democracies were least prepared, psychologically and militarily, to meet it; and just as they were less coordinated than at any time since the 1919 settlement. Whatever the deficiencies and follies of any particular “appeaser” in the unhappy 1930s, therefore, it is as well to bear in mind the unprecedented complexities with which the statesmen of that decade had to grapple.

考虑到上述的所有困难和欧洲在凡尔赛和约签订以后仅仅20年就又卷入了另一次大战,人们对历史学家把这一时期看作是“20年的休战”,并把它描述为一个令人沮丧的和破裂的时期,就丝毫不会感到奇怪了。因为这一时期充满着危机、欺诈、暴行和耻辱。但是,由于一些标有“一个破裂的世界”、“失去的和平”和“二十年的危机”这类题目的书籍描述的是整个这20年的历史,所以就存在着这样一个危险,即20世纪20年代和30年代之间的重大差异可能被忽视了。这里有必要重复一下本书前面所作的一个评论,即到20世纪20年代后期,《洛迦诺公约》和《凯洛格-白里安公约》(《巴黎非战公约》)的签订、法德之间许多分歧的解决、国际联盟的多次会议以及繁荣的全面恢复似乎表明,从国际关系的角度说来,第一次世界大战终于过去了。然而,仅仅只过了一两年,毁灭性的金融和工业崩溃就动摇了那种和谐的环境,并开始与日本和德国(及后来的意大利)的民族主义者对现存秩序提出的挑战相互影响。弹指之间,战争的乌云又重新布满了天空。当民主国家在心理上和军事上都缺乏应付战争的准备时,在它们处于1919年和解以来最不协调的状态之时,整个国际体系又从根本上受到了威胁。因此,在那个不幸的20世纪30年代里,不论哪一个特定的“绥靖主义者”的行为是多么错误和愚蠢,我们也应该记住,在那个10年里政治家们必须处理的问题是空前复杂的。

Before seeing how the international crises of this period unfolded into war, it is important once again to examine the particular strengths and weaknesses of each of the Great Powers, all of which had been affected not only by the 1914–1918 conflict but also by the economic and military developments of the interwar years. In this latter respect, Tables 12–18 above, showing the shifts in the productive balances between the powers, will be referred to again and again. Two further preliminary remarks about the economics of rearmament should be made at this point. The first concerns differential growth rates, which were much more marked during the 1930s than they had been, say, in the decade prior to 1914; the dislocation of the world economy into various blocs and the remarkably different ways in which national economic policy was pursued (from four-year plans and “new deals” to classic deflationary budgets) meant that output and wealth could be rising in one country while dramatically slowing down in another. Secondly, the interwar developments in military technology made the armed forces more dependent than ever upon the productive forces of their nations. Without a flourishing industrial base and, more important still, without a large, advanced scientific community which could be mobilized by the state in order to keep pace with new developments in weaponry, victory in another great war was inconceivable. If the future lay (to use Stalin’s phrase) in the hands of the big battalions, they in turn increasingly rested upon modern technology and mass production.

在观察国际危机怎样转移成战争之前,对每一大国的强势和弱点再一次进行考查仍是十分重要的。所有这些大国不仅受到1914~1918年战争冲突的影响,而且也受到两次大战期间经济和军事发展的影响。关于后一方面,前面的表12到表18指明了各大国的生产力量对比的变化情况,这些表内的数字将会被多次引用。在这方面应该就重新武装的经济学写两段序言。首先涉及的是不同的增长率,它在20世纪30年代比从前,比如说,比1914年以前的10年,有更明显的增长。世界经济分裂成各个集团和各自采用不同的方式(四年计划、“新政”和古典的紧缩通货预算)来执行的国家经济政策,意味着产量和财富在一个国家里增加的同时,在另一个国家里却可能戏剧性地衰退。其次,军事技术在两次大战之间的发展使得武装部队更加依赖于其国家的生产力。没有一个欣欣向荣的工业基础,尤其更为重要的是,没有一支大规模的、先进的国家可以动员起来以便与新武器发展保持同步的科技队伍,要在另一场大战中取得胜利简直是不可想象的。如果说未来掌握在大部队手中(斯大林语)的话,那么也可以说,它们反过来也日益依赖于现代技术和大生产。