The Challengers

战争策源地

The economic vulnerability of a Great Power, however active and ambitious its national leadership, is nowhere more clearly seen than in the case of Italy during the 1930s. On the face of it, Mussolini’s fascist regime had brought the country from the hinterlands to the forefront of the diplomatic world. With Britain, it was one of the outside guarantors of the 1925 Locarno agreement; with Britain, France and Germany, it was also a signatory to the 1938 Munich settlement. Italy’s claim to primacy in the Mediterranean had been asserted by the attack upon Corfu (1923), by intensifying the “pacification” of Libya, and by the very large intervention (of 50,000 Italian troops) in the Spanish Civil War. Between 1935 and 1937, Mussolini avenged the defeat of Adowa by his ruthless conquest of Abyssinia, boldly defying the League’s sanctions and hostile western opinion. At other times, he supported the status quo, moving troops up to the Brenner in 1934 to deter Hitler from taking over Austria, and readily signing the anti-German accord at Stresa in 1935. His tirades against Bolshevism won him the admiration of many foreigners (Churchill included) in the 1920s, and he was wooed by all sides during the decade following—with Chamberlain traveling to Rome as late as January 1939 in an effort to stop Italy from drifting completely into the German camp. 42

20世纪30年代的意大利足以说明一个大国经济上的脆弱性,而不论这个国家的领导者是多么积极主动和野心勃勃。乍看起来,墨索里尼的法西斯政权把国家从外交世界中的偏僻之地带到了世人瞩目的中心。同英国一起,意大利是1925年《洛迦诺公约》的外部保证者之一;同英国、法国和德国一起,意大利也是1938年《慕尼黑协定》的签字国。通过进攻科孚(1923年)、大力“平定”利比亚和大举(出动5万意大利军队)干涉西班牙内战,意大利保证了它称霸地中海的要求。1935年到1937年间,墨索里尼敢于蔑视国际联盟的制裁和西方的敌视态度,对阿比西尼亚(今埃塞俄比亚)进行了血腥的征服,从而雪洗了阿杜瓦惨败之辱。而在早些时候,墨索里尼却主张维持现状:1934年他出师布伦纳山口,以遏制希特勒接管奥地利;1935年,在斯特雷扎他又欣然同意签署反德协议。在20世纪20年代,墨索里尼滔滔不绝地抨击布尔什维主义的演说,使他赢得了许多外国人(包括丘吉尔在内)的钦佩,而在下一个10年(即30年代)他又成了各方讨好的对象。以致到了1939年1月,张伯伦的罗马之行还力图阻止意大利完全滑入德国阵营。

But diplomatic prominence was not the only measure of Italy’s new greatness. This fascist state, with its elimination of factious party politics, its “corporatist” planning for the economy in the place of disputes between capital and labor, its commitment to government action, seemed to offer a new model to a disenchanted postwar European society—and one attractive to those who feared the alternative “model” being offered by the Bolsheviks. Because of Allied investments, industrialization had proceeded apace from 1915 to 1918, at least in those heavy industries related to arms production. Under Mussolini, the state committed itself to an ambitious modernization program, which ranged from draining the Pontine marshes, to the impressive development of hydroelectricity, to the improvements in the railway system. The electrochemical industry was furthered, and rayon and other artificial fibers were developed. Automobile production was increased, and the Italian aeronautical industry seemed to be among the most innovative in the world, its aircraft gaining a whole series of speed and altitude records. 43

但是外交上的声望并不是衡量意大利重新崛起的唯一尺度。由于废除了闹派性的政党政治,在经济方面用“社团主义”计划取代了劳资争端以及关于政府行动所作的承诺,这个法西斯国家似乎为失望的战后欧洲社会提供了一个新的模式。这一模式对于那些惧怕布尔什维克所提供的另一种“模式”的人来说,是具有吸引力的。由于协约国的投资,1915~1918年,意大利的工业化取得了迅速的进展,至少在与武器生产有关的重工业领域里如此。在墨索里尼统治下,这个国家致力于一项雄心勃勃的现代化计划:排除庞廷沼泽的积水,大力发展水力发电,改善铁路系统。同时电气工业、人造丝及其他人造纤维也有发展。汽车产量增加了,航空工业也似乎进入了世界上最富有革新精神的国家之列,它的飞机在速度和高度上创造了一系列新纪录。

Military power, too, seemed to give good indications of Italy’s rising status. Although he had not spent much on the armed services in the 1920s, Mussolini’s belief in force and conquest and his rising desire to expand Italy’s territories led to significant increases in defense spending during the 1930s. Indeed, a little over 10 percent of national income and as much as one-third of government income was devoted to the armed forces by the mid-1930s, which in absolute figures was more than was spent by Britain or France, and much more than the American totals. Smart new battleships were being laid down, to rival the French navy and the British Mediterranean Fleet, and to support Mussolini’s claim that the Mediterranean was indeed mare nostrum. When Italy entered the war it possessed 113 submarines—“the largest submarine force in the world except perhaps that of the Soviet Union. ”44 Even larger sums were being allocated to the air force, the Regia Aeronautica, in the years leading up to 1940, in keeping perhaps with early fascism’s emphasis upon modernity, science, speed, and glamour. Both in Abyssinia and, even more, in Spain, the Italians demonstrated the uses of air power and convinced themselves—and many foreign observers—that they possessed the most advanced air force in the world. This buildup of the navy and the air force left fewer funds for the Italian army, but its thirty divisions were being substantially restructured in the late 1930s, and new tanks and artillery were being planned. Besides, Mussolini felt, there were the masses of fascist squadristi and trained bands, so that in another total war the nation might well possess the claimed “eight million bayonets. ” All this boded well for the creation of a second Roman Empire.

军事力量似乎也是意大利崛起的很好标志。虽然20世纪20年代它在武装部队上的花费并不多,但是墨索里尼对于实力和征服的迷信,以及扩张意大利领土的日益强烈的愿望,使他在30年代大幅度地增加国防开支。确实,在30年代中期,国民收入的10%以上和政府收入的1/3都被用于发展武装部队,按军费占财政支出的比重来说,比英国或法国的开支还要多,而比美国的总支出更多得多。时髦的新型战舰正在建造,为的是与法国海军和英国的地中海舰队相抗衡,并使地中海确实成为墨索里尼所宣称的“我们的海”。当意大利参战时,它拥有113艘潜水艇,“这或许是除了苏联以外世界上最庞大的潜水艇部队”。1940年以前,它甚至把更多的钱分配给空军,即皇家空军。这也许是为了与早期法西斯主义强调现代性、科学、速度和刺激性的论调保持一致。无论是在阿比西尼亚还是在西班牙(特别是在后者),意大利人都动用了空军,并使自己以及许多外国观察者确信他们拥有世界上最先进的空军。海军和空军的加强使意大利用于陆军的基金所剩无几,但是在30年代后期,陆军的30个师经过了实质上的改编,新式的坦克和火炮列入了计划。此外,墨索里尼认为,由于大量的法西斯行动队和训练有素的小分队的存在,因而在下一次总体战中,这个国家很可能拥有曾经要求的“800万士兵”。所有这些都是第二罗马帝国诞生的吉兆。

Alas for such dreams, fascist Italy was, in power-political terms, spectacularly weak. The key problem was that even “at the end of the First World War Italy, economically speaking, was a semideveloped country. ”45 Its per capita income in 1920 was probably equal to that achieved by Britain and the United States in the early nineteenth century, and by France a few decades later. National income data concealed the fact that per capita income in the north was 20 percent above, in the south 30 percent below, the average; and the gap, if anything, was widening. Thanks to a continued flow of emigrants, Italy’s population in the interwar years increased by only around 1 percent a year; since the gross domestic product grew by 2 percent a year, the average per capita rose by a mere 1 percent a year, which was not disastrous, but hardly an economic miracle. At the root of Italy’s weakness was the continued reliance upon small-scale agriculture, which in 1920 accounted for 40 percent of GNP and absorbed 50 percent of the total working population. 46 It was a further sign of this economic backwardness that even as late as 1938 over half a family’s expenditure went on food. Far from reducing these proportions, fascism, with its heavy emphasis upon the virtues of rural life, endeavored to support agriculture by a battery of measures, including protective tariffs, widespread land reclamation, and, finally, complete control of the wheat market. Important in the regime’s calculations was the desire to reduce dependence upon foreign food producers and the strong wish to prevent a further drift of peasants into the towns, where they would boost the unemployment totals and add to the social problem. The consequence was a very heavy under employment in the countryside, with all of the corresponding features: iow productivity, illiteracy, immense regional disparities.

然而,这些不过都是梦想,从强权政治的角度来看,法西斯主义的意大利软弱得惊人。关键问题在于,“从经济上说,甚至到第一次世界大战结束之时,意大利仍只能算是一个半发达的国家”。按人均收入,意大利1920年的水平或许只相当于英国和美国在19世纪初期及法国在19世纪中期所达到的水平。意大利国民收入数据掩盖了这样一个事实,即北部的人均收入高于平均水平20%,而南部的人均收入则低于平均水平30%。这一差距,要是说有什么变动,那就是还在不断地拉大。由于人口源源不断地外流,因而在两次世界大战期间,意大利人口的年增长率只有1%左右。国内生产总值的年增长率为2%,而人均收入的年增长率只有1%。这虽不能说是一种灾难,但也很难说是一种经济奇迹。从根本上说,意大利的软弱就在于它一直依赖于小规模的农业。1920年农业在国民生产总值中所占比重为40%,并吸收了劳动人口总数的50%。甚至直到1938年,意大利一个家庭的过半支出仍用于购买食物,这是经济落后的又一标志。由于过分强调农村生活的优点,法西斯主义不是减少农业的比重,而是采取一系列措施尽力支持农业,其中包括保护关税、大面积地开垦土地和完全控制小麦市场。在法西斯政权的各种考虑中,重要的是尽量减少对外国粮食生产者的依赖,防止农民进一步流入城镇,因为这会导致失业总人数的上升和社会问题的增多。其结果造成了农村极为严重的失业,并产生与此相应的所有特征:低生产率、文盲和地区间的严重不平衡。

Given the relatively backward nature of the Italian economy and the state’s willingness to spend money both on armaments and on the preservation of village agriculture, it is not surprising that the amount of savings for entrepreneurial investment was low. If the First World War had already reduced the stock of domestic capital, the economic depression and the turn to protectionism were further blows. To be sure, companies boosted by government orders for aircraft or trucks could make a good profit, but it is unlikely that Italy’s industrial development benefited (on the whole) from attempts at autarky; tariffs merely gave protection to inefficient producers, while the general neo-mercantilism of the age reduced the flow of foreign investments which had done much to stimulate Italian industrialization earlier. By 1938 Italy still possessed only 2. 8 percent of world manufacturing production, produced 2. 1 percent of its steel, 1. 0 percent of its pig iron, 0. 7 percent of its iron ore, and 0. 1 percent of its coal, and consumed energy from modern sources at a rate far below that of any of the other Great Powers. Finally, in the light of Mussolini’s evident eagerness to go to war against France, and sometimes even France and Britain combined, it is worth noting that Italy remained embarrassingly dependent upon imported fertilizer, coal, oil, scrap iron, rubber, copper, and other vital raw materials—80 percent of which had to come past Gibraltar or Suez, and much of which was carried in British ships. It was typical of the regime that no contingency plan had been prepared in the event of these imports ceasing, and that a policy of stockpiling such strategic materials was out of the question, since by the late 1930s Italy didn’t even have the foreign currency to cover its current needs. This chronic currency shortage also helps to explain why the Italians also could not afford to pay for the German machine tools so vital for the production of the more modern aircraft, tanks, guns, and ships which were being developed in the years after 1935 or so. 47

既然意大利经济相对落后,国家又宁愿把钱花在军备和维护乡村农业上,那么剩下来用于企业投资的金额就很少,这就不足为奇了。如果说第一次世界大战已经减少了国内资本的积累,那么经济萧条和转向保护主义对于国内资本的积累则是进一步的打击。可以肯定,因有政府的飞机或卡车订货而生意兴隆的公司可以大获盈利,但是总的说来,意大利经济发展不大可能从自给自足的努力中获益。关税仅仅为无效率的生产者提供了保护,而以前曾给意大利工业化以极大推动的国外投资,在这种全面的新重商主义时代却减少了。到1938年,意大利仍然只拥有世界制造业产量的2.8%,钢、生铁、铁矿石和煤产量在世界总产量中所占比重分别为2.1%、1.0%、0.7%和0.1%,它的现代资源的能源消耗率比任何其他大国都低得多。最后,鉴于墨索里尼明显地热衷于同法国打仗,有时还想与英法两国同时作战,指出下面这一点是有意义的:意大利仍然不得不依赖于肥料、煤、石油、废钢铁、橡胶、铜和其他必需原料的进口——其中80%要通过直布罗陀海峡和苏伊士运河,而且不少是由英国船只运载的。意大利政权在这方面最具典型性,即没有制订应付进口物资一旦停止的应急计划。这类战略原料的储存也是谈不上的,因为到30年代后期,意大利甚至没有外汇去支付眼前的需求。这种经常性的通货短缺也有助于解释为什么意大利人无力购买德国机床。这对于生产1935年以后研制出来的更新式的飞机、坦克、大炮和舰艇是至关重要的。

Economic backwardness also explains why, despite all the attention and resources which Mussolini’s regime devoted to the armed forces, their actual performance and condition were poor—and getting worse. The navy was probably the best-equipped of the three services, but probably too weak to drive the Royal Navy out of the Mediterranean. It possessed no aircraft carriers—Mussolini had forbidden their construction—and was forced instead to rely upon the Regia Aeronautica, a poor arrangement given the lack of interservice cooperation. Its cruisers were fairweather vessels, and its great array of submarines proved to be a heavy investment in obsolescence: “The boats lacked attack computers, their air-conditioning systems gave off poisonous gases when tubing ruptured under depth-charge attack, and they were relatively slow in diving, which proved embarrassing when enemy aircraft approached. ”48 Similar signs of obsolescence could be seen in the Italian air force, which had shown itself capable of bombing (if not always hitting) Abyssinian tribesmen, and had then impressed many observers by its Spanish Civil War performances. But by the late 1930s the Fiat CR42 biplane was totally eclipsed by the newer British and German monoplanes; and even the bomber force suffered from having only light to medium bombers, with weak engines and stupendously ineffective bombs. Yet both the above services had secured increasing shares of the defense budget. The army, by contrast, saw its share drop from 58. 2 percent in 1935–1936 to 44. 5 percent in 1938–1939, and that at a time when it desperately needed modern tanks, artillery, trucks, and communications systems. The “main battle tank” of the Italian army, when it entered the Second World War, was the Fiat L. 3, of three and a half tons, with no radio, little vision, and only two machine guns —this at a time when the latest German and French tank designs were close upon twenty tons and had much heavier weaponry.

尽管墨索里尼政权把全部精力和资源都用于武装部队的建设,但它们的实际表现和状况却很糟糕,而且每况愈下,这一点也可以从经济落后中找到解释。海军或许可以算作是意大利3个军种中装备最精良的,但是也可能过于软弱而无力把英国皇家海军逐出地中海。意大利海军没有航空母舰(因为墨索里尼禁止建造),因此它被迫转而依赖意大利皇家空军。军种之间缺乏协调,这可以说是一种极为不当的安排。它的巡洋舰只适宜于好天气,而事实证明它的大批潜水艇是一种对过时装备的巨额投资:“艇上缺少攻击计算仪器;在遭到深水炸弹攻击时一旦管道破裂,空调系统会放出有毒气体;下潜速度相当缓慢,这在敌机飞临时是很令人头疼的。”类似的落后现象在意大利空军中也可以看到。意大利空军在对阿比西尼亚部落的轰炸(虽然并不总是击中目标)中显示了自己的能力,它在西班牙内战中的表现也给许多观察家留下了深刻的印象。但是到30年代后期,更新式的英国和德国的单翼机完全使菲亚特CR42型双翼机黯然失色,甚至轰炸机部队也苦于只拥有轻型和中型轰炸机,这些飞机的发动机马力很小,炸弹也非常不灵。然而,意大利上述的这两个军种在国防预算中所享有的份额还是日益增加。相比之下,陆军在国防预算中的份额却从1935~1936年度的58.2%,下降到1938~1939年度的44.5%,而这个时期正是陆军迫切需要新式坦克、大炮、卡车和通信系统的时候。当意大利参加第二次世界大战时,意大利陆军的“主战坦克”是重量为3.5吨的菲亚特L-3型坦克,没有无线电设备,视野狭窄,只配备有两挺机枪;而这时最新式的德国和法国坦克设计重量都接近20吨,并装有威力大得多的火器。

Given the almost irremediable weaknesses which afflicted the Italian economy under fascism, it would be rash to suggest that it could ever have won a war against another proper Great Power; but its prospects were made the bleaker by the fact that its armed forces were the victims of early rearmament—and swift obsolescence. Since this was a common problem in the 1930s, affecting France and Russia to almost the same degree, it is important to go into it in a little more detail before returning to our specific analysis of Italy’s weaknesses.

鉴于法西斯统治下困扰意大利经济的几乎不可救药的软弱性,那种认为它能在同另一个相当的大国的战争中取胜的看法未免太轻率了。下面这一事实使意大利的前景更加暗淡,即它的武装部队是早期重新武装的牺牲品,因而很快就过时了。由于这在20世纪30年代是一个普遍问题,也几乎在同等程度上影响了法国和俄国,因此,我们在回头具体分析意大利的软弱性之前,稍微详细地探讨一下这个问题是很重要的。

The key factor was the intense application of science and technology to military developments in this period, which was transforming weapon systems in all the services. Fighter aircraft, for example, were swiftly changing from maneuverable (but lightly armed and fabric-covered) biplanes which could do about 200 mph to “duraluminum monoplane aircraft laden with multiple heavy machine guns and cannon, cockpit armor and self-sealing fuel tanks”49 which flew at up to 400 mph and required much more powerful engines. Bomber aircraft were changing—in those nations which could afford the move—from two-engined, shorter-range medium bombers to the massively expensive four-engined types capable of carrying large bomb loads and with a radius of over two thousand miles. Post-Washington Treaty battleships (e. g. , of the King George V, Bismarck, and North Carolina sort), were much faster, better-armored, and equipped with far heavier antiaircraft defenses than their predecessors. The newer aircraft carriers were large, welldesigned types, with a much greater striking power than the updated seaplane carriers and converted battle cruisers of the 1920s. Tank developers were rushing ahead with heavier, better-armed, and better-armored models which required far more powerful engines than those which had driven the light experimental prototypes of the pre-1935 years. Furthermore, all of these weapon systems were just beginning to be affected by the changes in electrical communications, by improvements in navigational devices and antisubmarine detection equipment, by early radar and improved radio equipment—which not only made the newer weapons so much more expensive, but also complicated the procurement process. Did one have enough of the new machine tools, gauges, and jigs to switch to these improved models? Could armaments works and electrical suppliers meet the rising demand? Did they have enough spare plant, and trained engineers? Dare one stop producing the tried but perhaps obsolescent older models while waiting for the newer types to be tested and then built? Finally—and critically—how did these desperate rearmament efforts relate to the state of the nation’s economy, its access to overseas as well as domestic resources, its ability to pay its way? These were, of course, not new dilemmas—but they pressed upon the decision-makers of the 1930s with a far greater urgency than ever before.

至关重要的因素是,这一时期的科学和技术广泛用于军事发展,它改变着所有兵种的武器系统。例如,战斗机就正在从便于操纵(但武器装备单薄)的双翼机,迅速转变为“装备多挺重机枪和火炮、座舱防弹钢板和自封式燃料箱”的铝合金单翼机,前者飞行时速约为200英里,后者飞行时速可达400英里,并需要更大功率的引擎。轰炸机也在发生变化——在那些有能力实现这一变化的国家里——从双引擎的短程中型轰炸机向代价高昂、四引擎、载弹量很大、活动半径达2000英里的轰炸机转变。《华盛顿条约》以后的战列舰(如乔治五世号、俾斯麦号和北卡罗来纳号等)比它们的前代航速加快了,防护能力增强了,并装备强大得多的防空火力系统。新式航空母舰是庞然大物,设计也很完善,比20世纪20年代最新式的水上飞机母舰和改装过的战列巡洋舰都有更大的攻击力。坦克设计师正在赶制更重型的、武器装备更好、防护钢板更强的坦克样品,这种坦克需装载比1935年以前的轻型实验原型所拥有的马力大得多的发动机。此外,所有这些武器系统正受到电力通信的变革、导航设备和潜探测设备的改善的影响,也受到早期雷达和改进了的无线电装备的影响。所有这些技术改进,不仅使新式武器变得更加昂贵,而且也使新式武器的采购程序复杂化了。试问,人们有足够的新式机床、计量仪器和焊接平台去适应这些改进型装备的生产吗?武器工厂和电力供应能够满足日益增长的需求吗?他们有足够的备用工厂和训练有素的工程师吗?人们有胆量停止生产经过考验的但可能是过时的旧式型号,而去等待新型号经过试验然后再投入生产吗?最后一个问题,也是至关重要的问题是,这些不顾一切重新武装的努力,怎样与国家经济状况、海内外资源的获得以及国家财政承受能力保持一致?毫无疑问,这一切并不是新出现的难题,但是这一切给30年代的决策者们的压力,要比以往任何时候都沉重得多。

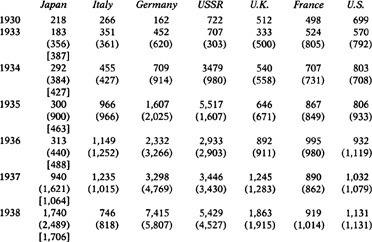

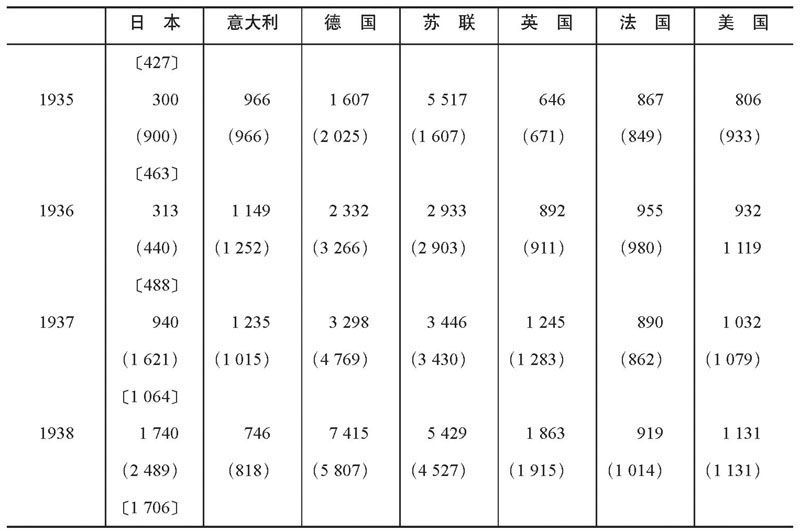

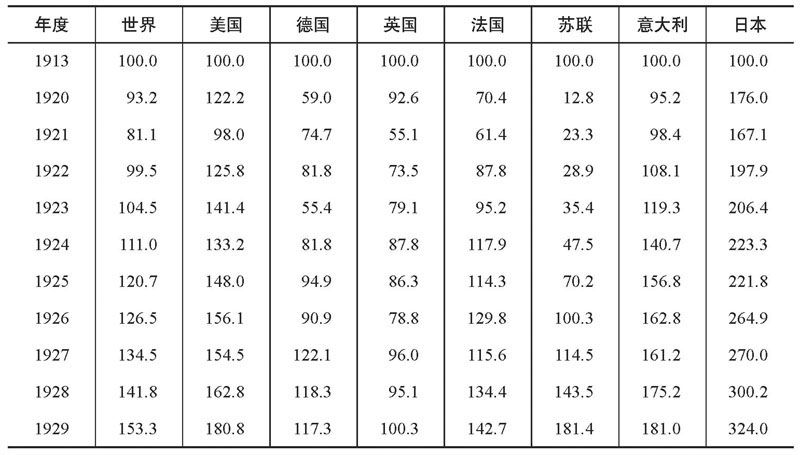

It is in this technological-economic context (as well as in the diplomatic context) that the varying patterns of Great Power rearmament in the 1930s can best be understood. There are many disparities in the compilation of the actual annual totals of defense expenditures by individual nations in this decade, but Table 27 can serve as a fair guide to what was happening.

正是在这种技术—经济背景(和外交背景)中,才能够最透彻地理解30年代大国重新武装的不同模式。在这10年中,各国国防开支实际年度总数的统计方式存在着许多差异,但是表27还是可以看作此时发生的事情的一个合理指南。

Table 27. Defense Expenditures of the Great Powers, 1930–193850

表27 大国国防开支(1930~1938年)

(millions of current dollars)

(以当时百万美元为单位)

Seen in this comparative light, the Italian problem becomes clearer. It had not been a great spender on armaments in absolute terms during the first half of the 1930s, although even then it had needed to devote a higher proportion of its national income to the armed services than probably all other states except the USSR. But the extended Abyssinian campaign, overlapped by the intervention in Spain, led to greatly increased expenditures between 1935 and 1937. Thus part of Italian defense spending in those years was devoted to current operations, and not to the buildup of the services or the armaments industry. On the contrary, the Abyssinian and Spanish adventures gravely weakened Italy, not only because of losses in the field, but also because the longer it fought, the more it needed to import—and pay for—vital strategic raw materials, causing the Bank of Italy’s reserves to shrink to almost nothing by 1939. Unable to afford the machine tools and other equipment needed to modernize the air force and the army, the country was probably getting weaker in the two to three years prior to 1940. The army was not helped by its own reorganization, since the device of creating half again as many divisions by simply reducing each division from three to two regiments led to many officer promotions but to no real increase in efficiency. The air force, supported (if that is the right word) by an industry which was less productive than that of 1915–1918, claimed that it had over 8,500 planes; further investigations reduced that total to 454 bombers and 129 fighters, few of which would be regarded as first-rate in other air forces. 51 Without proper tanks or antiaircraft guns or fast fighters or decent bombs or aircraft carriers or radar or foreign currency or adequate logistics, Mussolini in 1940 threw his country into another Great Power war, on the assumption that it was already won. In fact, only a miracle, or the Germans, could prevent a debacle of epic proportions.

通过这种对比,意大利的问题就更清楚了。尽管到20世纪30年代中期,意大利需要把相当大一部分国民收入用于武装部队(其比重可能超过除苏联以外的任何国家),但是从绝对数字来说,30年代前半期意大利在军备方面并不是一个高消费者。但是,旷日持久的阿比西尼亚战争,加上其间对西班牙的干涉,导致国防开支在1935~1937年大幅度增加。因此,在那几年里,意大利的部分国防开支是用于当时的军事行动,而不是用于三军或军事工业的发展。在阿比西尼亚和西班牙的冒险严重地削弱了意大利,这不仅仅是因为战场上的损失,而且还因为战斗持续得越久,意大利就越需要进口必不可少的战略原料,而这是需要付钱的,从而导致1939年意大利银行储备减少到几乎等于零。由于无力购买使空军和陆军现代化所需要的机床和其他设备,早在1940年之前的两三年,这个国家或许已经变得更弱了,陆军自身的整编也无济于事,因为它把每一个师从3个团减少为两个团,用这个办法把师的数目又增加一倍,其结果是许多军官得到了晋升,但部队的效率并没有真正提高。空军依靠生产力还不及1915~1918年的工业来支撑(假定这个词是恰当的),它号称拥有8500多架飞机,进一步的核实将这一数字减少到总共只有454架轰炸机和129架战斗机,其中没有多少在他国空军中堪称第一流的飞机。没有合适的坦克、高射炮、快速战斗机;像样的炸弹、航空母舰、雷达、外汇以及充足的后勤保障,墨索里尼就这样在1940年把它的国家投入了另一场大国战争,其根据就是这场战争已经打赢了这一设想。事实上,只有奇迹,或者说是德国人,才使意大利避免了一场空前的大灾难。

All of this emphasis upon weaponry and numbers does, of course, ignore the elements of leadership, quality of personnel, and national proclivity for combat; but the sad fact was that, far from compensating for Italy’s matériel deficiencies, those elements merely added to its relative weakness. Despite superficial fascist indoctrination, nothing in Italian society and political culture had altered between 1900 and 1930 to make the army a more attractive career to talented, ambitious males; on the contrary, its collective inefficiency, lack of initiative, and concern for personal career prospects was stultifying—and amazed the German attachés and other military observers. The army was not the compliant tool of Mussolini; it could, and often did, obstruct his wishes, offering innumerable reasons why things could not be done. Its fate was to be thrust, often without prior consultation, into conflicts where something had to be done. Dominated by its cautious and inadequately trained senior officers, and lacking a backbone of experienced NCOs, the army’s plight in the event of a Great Power war was hopeless; and the navy (except for the enterprising midget submarines) was little better off. If the officer corps and crews of the Regia Aeronautica were better educated and better trained, that would avail them little when they were still flying obsolescent aircraft, whose engines succumbed to the desert sands, whose bombs were hopeless, and whose firepower was pathetic. Perhaps it hardly needs saying that there was no chiefs of staff committee to coordinate plans between the services, or to discuss (let alone settle) defense priorities.

诚然,以上的分析强调的是武器和数字,没有考虑领导能力、人员素质和国民对于战争的态度等因素,然而可悲的事实是,这些因素不但远没有补偿意大利的物质缺陷,反而增加了它的相对软弱。尽管进行了肤浅的法西斯主义灌输,但在1900~1930年,意大利社会和政治文化中没有任何变化能使陆军对于有才能的、雄心勃勃的男性变得更有吸引力。恰恰相反,它集体性的低能、主动性的缺乏和对于个人前途的关心,使它显得丢人——这一切使德国武官和其他军事观察家感到惊愕。陆军并不是墨索里尼的已驯服的工具,它能够并且也确实是经常违反他的意愿,为完不成任务找出各种理由。它的命运就是,通常不经事先商量就被投入冲突,在那里总有些任务必须完成。在谨小慎微、未经充分培训的高级军官的指挥下,加之缺乏有经验的士官作为骨干,这支陆军一旦卷入大国战争,其境况是无望的。意大利海军(除了有魄力的袖珍潜艇之外)的境况也好不了多少。虽说皇家空军的军官团和飞行员受过良好的教育和训练,他们也无法施展才能,因为他们仍然驾驶着过时的飞机,这种飞机的发动机易受沙漠地区沙粒的损伤,炸弹不灵,而火力更是可怜。至于缺乏一个参谋长委员会来协调各军种的计划或者讨论(更不用说安排)防务上的轻重缓急,这一点就更无须赘述了。

Finally, there was Mussolini himself, a strategical liability of the first order. He was not, it has been argued, the all-powerful leader on the lines of Hitler which he projected himself as being. King Victor Emmanuel III strove to preserve his prerogatives, and succeeded in keeping the loyalties of much of the bureaucracy and the officer corps. The papacy was also an independent, and rival, focus of authority for many Italians. Neither the great industrialists nor the recalcitrant peasantry were enthusiastic about the regime by the 1930s; and the National Fascist Party itself, or at least its regional bosses, seemed more concerned with the distribution of jobs than the pursuit of national glory. 52 But even had Mussolini’s rule been absolute, Italy’s position would be no better, given II Duce’s penchant for self-delusion, resort to bombast and bluster, congenital lying, inability to act and think effectively, and governmental incompetence. 53

最后一点就是墨索里尼本人,他在战略上是头号的不利因素。有人论证说,墨索里尼并不是像希特勒那样无所不能的领袖,可他却使自己显得像那样的领袖。国王维克多·艾曼努埃尔三世努力维护他的君主特权,并成功地使官僚和军官团中的许多人对他保持忠诚。对于许多意大利人来说,罗马教廷也是一个独立的、颇有竞争力的权力中心。到20世纪30年代,大工业家和不驯顺的农民都对墨索里尼政权缺乏热情。而民族法西斯党本身,至少是它那些地区首领们,似乎更关心工作的分配,而不是追求民族的光荣。但是考虑到“领袖”的自我欺骗嗜好,喜欢言过其实和大吵大嚷,出于天性的撒谎,缺乏有效的行动和思考的能力,以及政府的无能等因素,即使墨索里尼的统治是绝对的,意大利的地位也不会更好一些。

In 1939 and 1940, the western Allies frequently considered the pros and cons of having Italy fighting on Germany’s side rather than remaining neutral. On the whole, the British chiefs of staff preferred Italy to be kept out of the war, so as to preserve peace in the Mediterranean and Near East; but there were powerful counterarguments, which seem in retrospect to have been correct. 54 Rarely in the history of human conflict has it been argued that the entry of an additional foe would hurt one’s enemy more than oneself; but Mussolini’s Italy was, in that way at least, unique.

1939~1940年,西方盟国经常考虑这样一个问题的利弊得失:让意大利参加德国一边作战,而不要让它保持中立。总的看来,英国三军参谋长们宁愿让意大利置身于战争之外,以便维持地中海和近东的和平,但是也存在着强有力的反对论调,它事后看来似乎是正确的。在人类冲突的历史上,论证出另一个敌人的参战给敌方造成的损害甚于己方,这种情况还是极为罕见的,而墨索里尼的意大利至少在这方面是独一无二的。

The challenge to the status quo posed by Japan was also of a very individual sort, but needed to be taken much more seriously by the established Powers. In the world of the 1920s and 1930s, heavily colored by racist and cultural prejudices, many in the West tended to dismiss the Japanese as “little yellow men”; only during the devastating attacks upon Pearl Harbor, Malaya, and the Philippines was this crude stereotype of a myopic, stunted, unmechanical people revealed for the nonsense it was. 55 The Japanese navy trained hard, both for day and night fighting, and learned well; its attachés fed a continual stream of intelligence back to the planners and ship designers in Tokyo. Both the army and the naval air forces were also well trained, with a large stock of competent pilots and dedicated crewmen. 56 As for the army proper, its determined and hyperpatriotic officer corps stood at the head of a force imbued with the bushido spirit; they were formidable troops both in offensive and defensive warfare. The fanatical zeal which led to the assassination of (allegedly) weak ministers could easily be transformed into battlefield effectiveness. While other armies merely talked of fighting to the last man, Japanese soldiers took the phrase literally, and did so.

日本对现状提出的挑战也是一个极为个别的类型,但是却需要公认的大国非常认真地去对待。20世纪20年代和30年代的世界强烈地带有种族和文化偏见的色彩。在西方,许多人往往把日本人作为“小黄种人”而不予以重视。只有在对珍珠港、马来亚和菲律宾的毁灭性进攻期间,人们才看清,那种把日本人看成是一个缺乏远见、发育不全和不懂机械的民族的陈腐观点完全是一派胡言。为了既能适应白天作战又能适应夜间作战,日本海军训练刻苦,并且收效甚丰;它的驻外武官源源不断地向东京的计划人员和舰船设计师提供情报。陆军航空队和海军航空兵也都训练有素,并储备了大批有能力的飞行员和具有献身精神的空勤人员。至于陆军本身,站在这支富于武士道精神的部队前面的,是意志坚强和极度爱国的军官团。无论是进攻作战还是防御作战,它们都是令人生畏的部队。那种导致行刺被指控为软弱的大臣的狂热情绪,很容易转变成战场上的效率。当其他军队仅仅是谈论战斗到最后一人时,日本士兵不仅是从字面上理解这句话,而且身体力行。

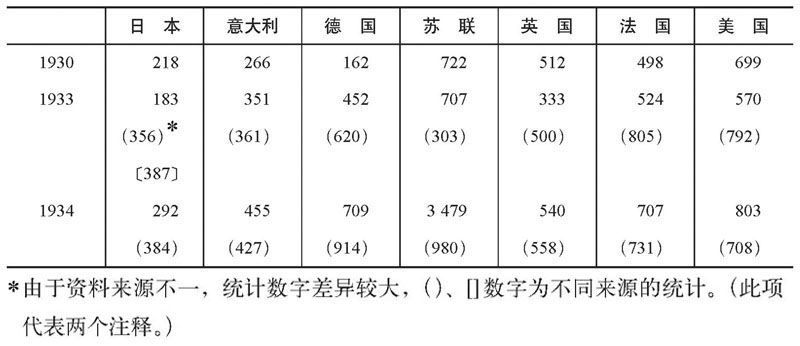

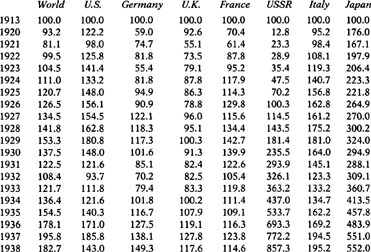

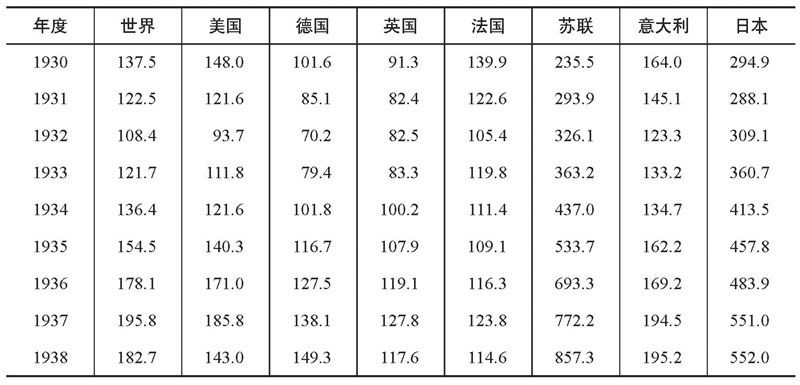

But what distinguished the Japanese from, say, Zulu warriors was that by this period the former possessed military-technical superiority as well as sheer bravery. The pre-1914 process of industrialization had been immensely boosted by the First World War, partly because of Allied contracts for munitions and a strong demand for Japanese shipping, partly because its own exporters could step into Asian markets which the West could no longer supply. 57 Imports and exports tripled during the war, steel and cement production more than doubled, and great advances were made in chemical and electrical industries. As with the United States, Japan’s foreign debts were liquidated during the war and it became a creditor. It also became a major shipbuilding nation, launching 650,000 tons in 1919 compared with a mere 85,000 tons in 1914. As the League of Nations World Economic Survey showed, the war had boosted its manufacturing production even more than that of the United States, and the continuation of that growth during the 1919–1938 period meant that it was second only to the Soviet Union in its overall rate of expansion (see Table 28).

这一时期的日本人如与非洲祖鲁武士相比,其区别在于前者不仅极为勇敢,而且还拥有军事—技术优势。第一次世界大战极大地促进了日本1914年以前的工业化进程,部分是因为协约国的军需品订货和对于日本船舶的迫切需求,部分是因为日本的出口商可以打进亚洲市场,而西方已不再能为亚洲市场提供商品了。在战争期间,日本进出口增加了两倍,钢和水泥产量增加了一倍多,化学工业和电气工业的发展也是突飞猛进。和美国一样,战争期间日本也还清了外债,并转而成为债权国。日本也变成了一个主要造船国,1919年下水吨位为65万吨,而1914年还只有8.5万吨。正如国际联盟的《世界经济概览》所表明的,战争对日本制造业产生的刺激比对美国的还大,而在1919~1938年生产的持续发展,意味着在总体发展速度方面日本仅次于苏联而居于第二位(参见表28)。

Table 28. Annual Indices of Manufacturing Production, 1913–193858

表28 制造业生产的年度指数(1913~1938年)

(1913 = 100)

(以1913年~100为比较)

By 1938, in fact, Japan had not only become much stronger economically than Italy, but had also overtaken France in all of the indices of manufacturing and industrial production (see Tables 14–18 above). Had its military leaders not gone to war in China in 1937 and, more disastrously, in the Pacific in 1941, one is tempted to conclude that it would also have overtaken British output well before actually doing so, in the mid-1960s.

事实上,到1938年,日本在经济上不仅变得比意大利强大,而且在所有制造业和工业生产指数方面也都超过了法国(见表14~表18)。如果日本军事领导人在1937年不发动对中国的战争,如果他们在1941年不发动更具灾难性的太平洋战争,那么,人们可能会得出这样的结论,即日本也许提前许多年就实现了它到20世纪60年代中期才实现的超过英国产量这一目标。

This is not to say that Japan had effortlessly overcome all of its economic problems, but merely that it was growing markedly stronger. Because of its primitive banking system, it had not found it easy to adjust to becoming a creditor nation during the First World War, and its handling of the money supply had caused great inflation—not to mention the “rice riots” of 1919. 59 As Europe resumed its peacetime production of textiles, merchant vessels, and other goods, Japan felt the pressure of renewed competition; the cost of its manufacturing, at this stage, was still generally higher than in the West. Furthermore, a heavy proportion of the Japanese population remained in small-plot agriculture, and these groups suffered not only from rising rice imports from Taiwan and Korea, but also from the collapse of the vital silk export trade when American demand fell away after 1930. Seeking to alleviate these miseries by imperial expansion was always a temptation for worried or ambitious Japanese politicians—the conquest of Manchuria, for example, meant economic benefits as well as military gains. On the other hand, when Japanese industry and commerce recovered during the 1930s, partly through rearmament and partly through the exploitation of captive East Asian markets, so its dependence upon imported raw materials grew (in this respect, at least, it was similar to Italy). As the Japanese steel industry expanded, it required larger amounts of pig iron and ore from China and Malaya. Domestic supplies of coal and copper were also inadequate for industry’s requirements; but even that was less critical than the country’s near-total reliance upon petroleum fuels of all sorts. Japan’s quest for “economic security”60—a self-evident good in the eyes of its fervent nationalists and the military rulers—drove it ever forward, but with mixed results.

这并不是说日本轻而易举地克服了它所有的经济困难,而只是说它引人注目地日益强大起来。由于其原始的银行体系,日本在第一次世界大战期间发现要适应一个债权国的地位也并非易事,而对于货币供应量的处理又导致严重的通货膨胀,更不用说1919年的“米骚动”了。当欧洲恢复了和平时期的纺织品、商船和其他商品的生产时,日本重又感到了竞争的压力;在这一时期,日本的制造业产品成本从总体上说仍然比西方高。另外,日本人口的绝大多数仍然停留在小规模农业经营上,这些农民不仅受到因从中国台湾和朝鲜进口的谷物日益增加的损害,而且也受到极其重要的丝织品出口贸易崩溃的损害,因为1930年以后美国对这方面的需求消失了。对于忧心忡忡的或是野心勃勃的日本政治家来说,寻求通过帝国主义扩张以减轻这些苦难一直具有诱惑力,例如,对中国东北的征服不仅意味着军事上的得手,而且也意味着经济上的获益。另一方面,20世纪30年代,当日本的工业和商业部分通过重新武装,部分通过对被控制的东亚市场进行剥削而得到恢复以后,它对于进口原料的依赖也加深了(至少在这方面,日本与意大利有相似之处)。随着钢铁工业的发展,日本对中国和马来亚生铁和矿石的需求量也增加了。煤和铜的国内供应也不能满足工业的需要,但是与全国几乎完全依赖于各种石油燃料的进口相比,这些问题还不算是至关紧要的。日本对于“经济安全”的要求(在狂热的民族主义者和军国主义统治者的眼中,这是一种不言而喻的利益)驱使它永远向前,但是结果却并不尽如人意。

Despite—and, of course, in some ways because of—these economic difficulties, the finance ministry under Takahashi was willing to borrow recklessly in the early 1930s in order to allocate more to the armed services, whose share of government spending rose from 31 percent in 1931–1932 to 47 percent in 1936–1937;61 when he finally took alarm at the economic consequences and sought to modify further increases, he was promptly assassinated by the militarists, and armaments expenditures spiraled upward. By the following year, the armed services were taking 70 percent of government expenditure and Japan was thus spending, in absolute terms, more than any of the far wealthier democracies. Thus the Japanese armed services were in a far better position than those of Italy by the late 1930s, and possibly also those of France and Britain. The Imperial Japanese Navy, legally restricted by the Washington Treaty to slightly over half the size of either the British or American navy, was in reality much more powerful than that. While the two leading naval powers economized during the 1920s and early 1930s, Japan built right up to the treaty limits—and, indeed, secretly went far beyond them. Its heavy cruisers, for example, displaced closer to 14,000 tons than the 8,000 tons required by the treaty. All of the Japanese major warships were fast and very heavily armed; its older battleships had been modernized, and by the late 1930s it was laying down the gigantic Yamato-class vessels, larger than anything else in the world. The most important element of all, although the battleship admirals didn’t properly realize it, was Japan’s powerful and efficient naval air service, with 3,000 aircraft and 3,500 pilots, which centered upon the ten carriers in the fleet but also included some deadly-efficient bomber and torpedo-carrying squadrons on land. Japanese torpedoes were of unequaled power and quality. Finally, the country also possessed the world’s third-largest merchant marine, although (curiously) the navy itself virtually neglected antisubmarine warfare. 62

尽管有这些经济问题,而且在某些方面无疑正是由于这些经济问题的存在,使20世纪30年代早期高桥是清领导下的大藏省想不顾一切地借债,以便给军队分配更多的资金,导致军费在政府支出中的份额由1931~1932年度的31%,增加到1936~1937年度的47%。最后当高桥是清对经济后果感到惊恐并力图限制军费的进一步增加时,军国主义者立刻刺杀了他,而军费支出则螺旋式上升。第二年,武装部队支出在政府开支中的比重高达70%,就绝对数来说,日本的军费开支超过了所有比它远为富裕的民主国家。这样,到30年代末,日本军队的处境相比意大利军队要好得多,相比法英两国军队,也可能好得多。根据《华盛顿条约》,日本帝国海军规模在法律上被限制在英国或美国海军的一半稍多一点儿,但事实上它比两国海军要强大得多。在20年代和30年代早期这一段时间里,当英美两个主要的海军国家节约它们的海军开支时,日本的海军建设就达到了条约限制的规模,进而不声不响地远远突破了那些限制。例如,它的重巡洋舰的排水量接近1.4万吨,比条约规定的多0.8万吨。日本的所有主要战列舰的航速都很快.而且配有威力强大的武器。它的旧式战列舰实现了现代化。到30年代后期,日本正在建造“大和”级巨型战列舰,其吨位之大为世界之最。在所有因素中,最为重要的因素是(尽管日本的战列舰将领们还没有充分地认识到这一点)日本强大而有效的海军航空力量,它拥有3000架飞机和3500名飞行员,主要集中于海军的10艘航空母舰上,但也包括陆地上效率极高的轰炸机和鱼雷机中队。日本的鱼雷在威力和质量上都是无敌的。最后,这个国家还拥有居世界第三位的庞大商船队,但海军本身却令人难以理解地忽视了反潜战。

Because of conscription, the Japanese army had ready access to manpower and could ingrain the recruits into its traditions of absolute obedience and mass maximum effort. While it had kept the size of the army limited in earlier years, its expansion program saw the 24 divisions and 54 air squadrons of 1937 grow to 51 active service divisions and 133 air squadrons by 1941. In addition, there were 10 depot divisions (for training), and a large number of independent brigade and garrison troops, probably equal to another 30 divisions. By the eve of war, therefore, Japan had an army of over 1 million men, backed by nearly 2 million trained reserves. It was not strong in tanks, for which neither the terrain nor the wooden bridges of much of East Asia were suitable, but it had good mobile artillery and was well trained for jungle work, river crossings, and amphibious landings. The army’s 2,000 first-line aircraft (like the navy’s) included the formidable Zero fighter, as fast and maneuverable as anything produced in Europe at the time. 63

由于实行征兵制,日本陆军随时可以获得人力补充,并能使新兵完全遵循绝对服从和群体竭尽全力的传统。它原先保持着早些年所规定的陆军规模,后来执行扩军计划,从1937年的24个师、54个飞行中队,扩大到1941年的51个现役师、133个飞行中队。另外,还有10个兵站师(用于培训)及大批的独立旅和卫戍部队,大约相当于30个师。因此,到战争前夕,日本陆军已超过100万人,并得到将近200万训练有素的预备队的支持。坦克部队不够强大,因为东亚许多地区的地形和木桥不适于使用坦克,但是它装备着优良的机动火炮,经受过丛林作业、强渡江河和两栖登陆的良好训练。陆军有2000架可供作战的飞机(和海军的一样),包括令人生畏的零式战斗机,在速度和机动性能方面,它可以同当时欧洲生产的任何飞机相媲美。

Japan’s military effectiveness, therefore, was extremely high; but it was not free of weaknesses. Government decision-making in the 1930s was rendered erratic and, at times, incoherent by clashes between the various factions, by civil-military disputes, and by assassinations. In addition, there was the lack of proper coordination between the army and the navy—not a unique situation by any means, but the more dangerous in Japan’s case since each service had a quite different enemy and area of operations in mind. While the navy anticipated a future war with either Britain or the United States, the army’s eyes were fixed exclusively upon the Asian continent and the threat to Japanese interests there posed by the Soviet Union. Since the army was much more influential in Japanese politics and also dominated imperial general headquarters, its views generally prevailed. There was no effective opposition, from either the navy or the foreign office, although both were reluctant, when in 1937 the army insisted upon taking further action against China following the contrived Marco Polo Bridge incident. Despite a large-scale invasion of northern China from Manchurian soil, and landings along the Chinese coast, the Japanese army found it impossible to achieve a decisive victory. While losing great numbers of troops, Chiang Kai-shek kept up the struggle and moved even farther inland, pursued by Japanese striking columns and aircraft. The problem for Imperial General Headquarters was not so much the losses this campaigning involved—the army probably suffered only 70,000 casualties—but the stupendous costs of such inconclusive and extended warfare. By the end of 1937, there were over 700,000 Japanese troops in China, a number which steadily increased (though Willmott’s figure of 1. 5 million by 1938 seems far too high)64 without ever managing to force the Chinese to surrender. The “China Incident,” as Tokyo referred to it, was now costing $5 million a day and causing an even larger rise in defense spending. Rationing was introduced in 1938, as were a whole series of enactments which virtually put Japan onto a “total war” mobilization. The national debt spiraled upward at an alarming rate as the government borrowed more and more to pay for the enormous defense expenditures. 65

因此,日本的军事效力是非常高的,但是并非没有弱点。由于各派之间的倾轧而不团结,文武不和以及动辄就实行暗杀,使得30年代日本政府的决策缺乏稳定性,有时没有章法。此外,陆军和海军之间也缺乏适当的协调。当然这绝不是日本特有的现象,但是由于日本陆海军心目中各有一个完全不同的敌人和作战区域,因而这个问题对于日本就变得更加危险了。当海军预期在未来的战争中与英国或是美国交战时,陆军的眼睛却死盯着亚洲大陆和苏联对日本利益构成的威胁。由于陆军在日本政治中更有势力,而且还控制着帝国最高统帅部,因此一般来说它的观点是占上风的。在1937年日本蓄意制造卢沟桥事变以后,陆军坚持要对中国采取进一步的行动,这一决定并没有遭到海军和外务省的有效反对,虽然两者对这一决定的支持显得勉强。尽管日本从中国东北向华北发动了大规模进攻,并在中国沿海采取了登陆行动,但日本陆军仍发现它不可能取得决定性胜利。蒋介石政府虽然丧失了大批军队,但仍在坚持斗争,并且在日本突击纵队和飞机的追击下,向更纵深的内地转移。对于日本帝国最高统帅部来说,问题不是这次战争所遭受的损失(陆军伤亡大概只有7万人),而是这种没完没了、旷日持久战争的巨额开支。到1937年底,在中国的日本军队已超过70万人,而且这一数字还在不断增加(威尔莫特说到1938年有150万,这一数字似乎是太高了),但仍无法迫使中国人投降。“支那事变”——东京是这样称呼这场战争的——每天的费用是500万美元,从而导致军费更大幅度增长。1938年日本实行了配给制,连同一整套其他政令,实际上把日本推上了“总体战”动员的道路。随着日本政府越来越多地依靠借款来支付巨额军费,国债以惊人的速度螺旋上升。

What made this strategy even more difficult to sustain was Japan’s shrinking stocks of foreign currency and raw materials, and her increasing dependence upon imports from the disapproving Americans, British, and Dutch. After her air forces had used up large amounts of fuel in the China campaigns, “factories were ordered to reduce their fuel by 37 percent, ships by 15 percent and automobiles by 65 percent. ”66 This situation was the more intolerable to the Japanese since they believed that Chiang Kai-shek’s forces were only able to keep up their resistance because of the flow of western supplies, via the Burma Road, French Indochina, or other routes. Logically, inexorably, the conviction grew that Japan would have to strike south, both to isolate China and to gain a firm grip upon the oil and other raw materials of Southeast Asia, the Dutch East Indies, and Borneo. This was, of course, the direction which the Japanese navy had always favored; yet even the army, despite its prior concern about the Soviet Union and its extensive operations in China, was forced slowly to admit that action was necessary to ensure Japan’s economic security.

使这一战略变得更加难以维持的是日本外汇和原料贮存的日益减少,以及它对于持非难态度的美国、英国和荷兰进口的依赖性日益增长。当它的空军在中国战场上中耗尽了大量燃料以后,日本就“命令工厂、船只和机动车辆各减少它们燃料的37%、15%和65%”。日本人认为,蒋介石的军队之所以能够连续抵抗,是因为通过缅甸公路、法属印度支那和其他路线得到了西方源源不断的物资供应,这种情况更令日本人不能忍受。日本必须南进以孤立中国并牢固控制东南亚、荷属东印度和婆罗洲的石油及其他原料,这一信念合乎逻辑地、不可抗拒地增强着。当然,这是日本海军历来赞成的方针,然而即使是优先考虑苏联和在中国进一步作战的陆军,也被迫逐渐承认南进对于保障日本经济安全的重要性。

however, for the Japanese to go to war against either Russia or the United States. In the prolonged and bloody border clashes with the Red Army around Nomonhan between May and August 1939, for example, Imperial General Headquarters was alarmed at the clear superiority of Soviet artillery and aircraft, and at the firepower of the much larger Russian tanks. 67 With the Kwantung (Manchuria) army possessing only half the number of divisions that the Russians had placed in Mongolia and Siberia, and with large forces increasingly bogged down in China, even the more extremist army officers recognized that war against the USSR had to be avoided—at least until the international circumstances were more favorable.

这就导致了所有问题中最严重的问题。日本人在20世纪30年代后期建立起来的武装部队,可以轻而易举地把法国人赶出印度支那,把荷兰人赶出东印度。正如白厅的战略计划人员在30年代末秘密承认的那样,甚至英帝国也会发现,要顶住日本人的进攻是极为困难的;而且战争既已在欧洲爆发,英国要在远东全力以赴也是不可能的。然而,对于日本人来说,同苏联或是同美国交战则完全是另一回事了。例如,1939年5月到7月间在诺门罕周围与苏联红军的持续而血腥的冲突中,苏联在大炮、飞机、重型坦克的火力等方面的明显优势震惊了日本最高统帅部。日本关东军所拥有的师,不及苏联人部署在蒙古和西伯利亚的师的一半,大批军队在中国日益陷入困境。在这种情况下,甚至那些更为极端主义的陆军军官们也承认,必须避免同苏联作战,至少是在国际形势变得对日本更加有利之前应当如此。

But if a northern war would expose Japan’s limitations, would not a southern one also, if it ran the risk of bringing in the United States? And would the Roosevelt administration, which so strongly disapproved of the Japanese actions in China, stand idly by while Tokyo helped itself to the Dutch East Indies and Malaya, thereby escaping from American economic pressure? The “moral embargo” upon the export of aeronautical materials in June 1938, the abrogation of the American-Japanese trade treaty in the following year, and, most of all, the British-Dutch-U. S. ban of oil and iron-ore exports following the Japanese takeover of Indochina in July 1941 made it clear that “economic security” could be achieved only at the price of war with the United States. But the United States had nearly twice the population of Japan, and seventeen times the national income, produced five times as much steel, and seven times as much coal, and made eighty times as many motor vehicles each year. Its industrial potential, even in a poor year like 1938, was seven times larger than Japan’s;68 it might in other years be nine or ten times as large. Even granted the high level of Japanese patriotic fervor and the memory of its staggering successes against far larger opponents in 1895 (China) and 1905 (Russia), what it was now planning bordered on the incredible—and the absurd. Indeed, to such sober strategists as Admiral Yamamoto, an attack upon a country as powerful as the United States seemed folly, especially when it became clear that most of the Japanese army would remain in China; yet not to take on the United States after July 1941 would leave Japan exposed to western economic blackmail, which was also an intolerable notion. Unable to go back, the Japanese military leaders prepared to plunge forward. 69

但是,如果说战争北进将会暴露日本的局限性,那么战争南进如果冒着把美国卷入的危险,不是也会暴露日本的局限性吗?面对东京擅自夺取荷属东印度和马来亚,难道对于日本在中国的行动强烈不满的罗斯福政府会袖手旁观,从而使日本摆脱美国的经济压力吗?1938年6月实施的航空物资出口的“道义禁运”,第二年《美日商务条约》的废除,以及最重要的,即1941年7月日本夺取印度支那以后,英、荷、美三国联合实施的石油和铁矿禁运,所有这些都表明,日本只有不惜与美国开战,才能换取日本的“经济安全”。但是美国人口近乎日本人口的两倍,每年的国民收入是日本的17倍,钢产量是日本的5倍,煤产量是日本的7倍,机动车产量是日本的80倍。即使在像1938年这样不景气的年份里,美国工业潜力也比日本大7倍,而在其他年份则可能大9倍或10倍。即使考虑到日本人狂热的爱国主义热情和对远为庞大之敌的两次辉煌胜利(1895年对中国、1905年对俄国)的记忆,其当时筹划的战争也是不可思议的,甚至是荒谬的。事实上,对于像山本五十六将军这样清醒的战略家来说,进攻像美国这样强大的国家似乎是愚蠢的,特别是当大多数日本军队将留在中国这一点已经显而易见之时更是如此。然而1941年7月以后,日本如果不与美国决一雌雄,就会让日本暴露在西方经济胁迫之下,而这也是令其不能容忍的想法。欲罢不能,日本的军事领导者们准备铤而走险了。

In the 1920s, Germany appeared to be by far the weakest and most troubled of those Great Powers which felt dissatisfied by the postwar territorial and economic arrangements. Shackled by the military provisions of the Versailles Treaty, burdened by the need to pay reparations, constrained strategically by the transfer of border regions to France and Poland, and convulsed internally by inflation, class tension, and the corresponding volatility and confusion of the electorate and the parties, Germany possessed nothing like the freedom of action in foreign affairs enjoyed by Italy and Japan. While things had vastly improved by the late 1920s in consequence of the general prosperity and of Stresemann’s successes in enhancing Germany’s position by diplomacy, the country still was a politically troubled “half-free” Great Power when the financial and commercial crises of 1929–1933 devastated both its precarious economy and its much-disliked Weimar democracy. 70

20世纪20年代,德国显得异常虚弱。由于几个大国不满足于战后的领土和经济安排,德国因此而饱尝苦果:由于受到《凡尔赛和约》中军事条款的束缚,德国背着必须赔偿战争损失的沉重包袱;在战略上,由于把边界地区移交给法国和波兰而受到钳制;在国内,面临着通货膨胀、尖锐的阶级矛盾、选民和各党派的相应不稳定以及混乱的冲击;在外交事务上,德国一点儿享受不到意大利和日本所享有的行动自由。20年代后期,由于普遍繁荣的出现,同时由于施特雷泽曼在外交上成功地提高了德国的地位,各方面的情况得到了很大改善。但尽管如此,德国仍然是一个政治上处于困境的“半自由”大国,而此时,1929~1933年的金融和商业危机,沉重打击了它那不稳定的经济和令人厌恶的魏玛民主。

If the advent of Hitler transformed Germany’s position in Europe within a matter of years, it is important to recall the points made earlier: that virtually every German was a “revisionist” to a greater or lesser degree and much of the early Nazi foreign-policy program represented a continuity with the past ambitions of German nationalists and the suppressed armed forces; that the 1919–1922 border settlements in east-central Europe were seen as unsatisfactory by many other nations and ethnic groups, who pressed for changes long before the Nazis seized power, and were willing to join Berlin in amending them; that Germany, despite its losses of territory, population, and raw materials, retained the industrial potential to be the greatest of the European powers; and that the international balances which were needed to contain a resurgence of German aggrandizement were now far more disparate, and much less coordinated, than prior to 1914. That Hitler soon achieved staggering successes in his scheme to improve Germany’s diplomatic and military position is undoubted; but it is also clear that many existing circumstances favored his ruthless exploitation of opportunities. 71

如果说希特勒在上台后的几年里改变了德国在欧洲的地位,那么在此回顾一下前面曾提到的几点是很重要的。实际上,每个德国人都是“修正主义者”,只是程度不同而已;许多早期纳粹外交政策计划,体现了过去德国民族主义者的野心和受到压制的武装部队要一展雄心的延续性;1919~1922年中欧东部边界协定在许多民族和种族群体看来是不能令人满意的,早在纳粹分子掌权之前,他们就迫切要求改变现状,并且愿意同柏林结盟以期修订那些协定;尽管德国领土缩小,人口和原材料减少,但德国仍然保持着成为欧洲第一强国的工业潜能;抑制德国扩张的复苏是维持国际间平衡的需要,但这种平衡同1914年以前相比显得更加不伦不类且极不协调;毫无疑问,希特勒不久后就在他改善德国外交和军事地位的计划方面取得了惊人的成功;但同样明显的是,许多条件对他无情地利用这些机会也是有利的。

Hitler’s “specialness,” so far as the themes pursued in this book are concerned, lay in two areas. The first was the peculiarly intense and manic nature of the National Socialist Germany which he intended to create: a society racially “purified” by the elimination of Jews, gypsies, and any other allegedly non-Teutonic elements; a people whose minds and souls were given over to unquestioned support of the regime, which would thereby replace the older loyalties of class, church, region, and family; an economy mobilized and controlled for the purposes of expanding Deutschtum whenever or wherever the leader decreed that to be necessary, and against however many of the Great Powers; an ideology of force and struggle and hatred, which rejoiced in smashing foes and scorned the very idea of compromise. 72 Given the size and complexity of twentieth-century German society, it hardly needs remarking that this was an unreal vision: there were “limits to Hitler’s power”73 across the country; there were individuals, and interest groups, which supported him in 1932–1933, and even until 1938–1939, but with decreasing enthusiasm; and no doubt for all those who openly opposed the regime there were many others who developed a mentally internalized resistance. But despite such exceptions, there was also no question that the National Socialist regime was immensely popular and— even more important—absolutely unchallenged in respect to its disposition of national resources. With a political culture bent upon war and conquest and a political economy distorted to the extent that by 1938 52 percent of government expenditure and a massive 17 percent of gross national product was being poured into armaments, Germany had entered a different league from any of the other western European states. In the year of Munich, indeed, Germany was spending more upon weapons than Britain, France, and the United States combined. Insofar as the state apparatus could concentrate them, all German national energies were being mobilized for a renewed struggle. 74

就本书所要论述的主题而言,希特勒的“独特之处”表现在两个方面。第一个方面是,希特勒矢志要创建的民族社会主义德国的极端强烈和狂热的本质:这是一个通过灭绝犹太人、吉卜赛人和其他被怀疑为非条顿族的人种,来达到种族“纯洁化”的社会;一个将全心全意、毫无疑义地支持这个政权的民族,这个政权将取代阶级、教会、地区和家庭等古老的忠诚观念;一种不论何时何地,只要领袖认为需要,就能以推广德意志精神为目标而动员组织起来的、能与多数大国相抗衡的经济;一种充满了暴力、斗争和仇恨,以粉碎敌人为快乐和蔑视妥协的意识形态。设想一下20世纪德国社会的规模和复杂性,可以说几乎无须评论这是一种不现实的幻想了:希特勒在全国的“权力是有限的”。的确,1932~1933年,甚至1938~1939年以前曾支持他的个人与利益集团的热情在不断下降;毫无疑问,除了所有那些公开反对这个政权的人外,还有许多思想深处发生变化、产生了反抗情绪的人。尽管有这些例外的情况存在,但毋庸置疑的是,民族社会主义受到了广泛欢迎,甚至更为重要的是,它对自然资源的支配绝不会受到挑战。由于德国政治文化的重心集中在战争和征服上,以至于其政治经济扭曲到这样一种程度:1938年政府开支的52%和国民生产总值的17%都倾注在扩充军备上,因此,德国走上了一条不同于其他西欧国家的道路。《慕尼黑协定》签订的那一年,德国的军费开支实际比英国、法国和美国三国加在一起的总数还多。在国家机器所能影响的范围内,整个德国所有的力量都被动员起来准备参加新的战争。

The second major feature of German rearmament was the frighteningly precarious state of the national economy as it heated up during this expansion. As has been noted above, both the Italian and the Japanese economies manifested similar problems by the late 1930s—and the same would happen to France and Britain when they sought to respond to the fantastic pace of arms increases. But in none of those countries was the buildup of the armed forces as sudden as in Germany. In January 1933 its army was, legally, supposed to be no more than 100,000 men, although well before Hitler’s accession the military had secret plans to expand from a seven-division force to a twenty-one division force—just as it had privately prepared for the reestablishment of an air force, tank formations, and other elements banned by the Versailles Treaty. Hitler’s general instruction of February 1933 to von Fritsch, “to create an army of the greatest possible strength,”75 was simply taken by the planners to be the go-ahead to turn the earlier scheme into effect, free at last from financial and manpower restrictions. By 1935, however, conscription was announced and the army’s ceiling raised to thirty-six divisions. The acquisition of Austrian units in 1938, the takeover of the Rhineland military police, the creation of armored divisions, and the reorganization of the Landwehr sent that figure ever higher. In the crisis period of late 1938, the army totaled forty-two active, eight reserve, and twenty-one Landwehr divisions; by the next summer, when the war began, the German field army’s order of battle listed 103 divisions—a jump of thirty-two within one year. 76 The Luftwaffe’s expansion was even greater and faster. German aircraft production of a mere thirty-six planes in 1932 rose to 1,938 in 1934 and 5,112 in 1936, and the service’s twenty-six squadrons (July 1933 directive) rose to 302 squadrons, with over 4,000 front-line aircraft, at the outset of war. 77 If the navy was less impressive in size, then that was to a large degree due to the fact that (as Tirpitz earlier discovered) the creation of a powerful battle fleet took at least one to two decades. Nonetheless, by 1939 Admiral Raeder commanded a number of fast, modern warships, the navy had five times the number of personnel that it possessed in 1932, and it was spending twelve times as much as before Hitler came to power. 78 At sea, as well as on land and in the air, the German rearmament program was intent upon altering the balance of power as soon as possible.

第二个方面是,德国在扩充军备过程中,国民经济由于受到激发而处于惊恐的不稳定状态。正如前面所指出的,30年代后期,意大利和日本的经济也出现了相类似的问题,当法国和英国寻求对付那种令人难以置信的军备扩充步伐时,也遇到了同样的问题。但是,没有一个国家的武装部队增长的速度能像德国那样快。1933年1月,按合法规定,德国陆军人数大约不超过10万。在希特勒上台之前,军方即已在秘密筹划把7个师的部队扩充到21个师,与此同时,还暗中准备重建空军部队、坦克部队以及《凡尔赛和约》所禁止的其他兵种。1933年2月,希特勒给冯·弗里奇的总指示是“创建一支力量可能最强大的军队”。这一指示立即被扩军计划的制订者当作前进的号令,从而把以前制订的计划付诸实施,并最终摆脱了财政和人力上的限制。1935年,德国宣布征兵,军队的最大数量上升到36个师。1938年,德国接收了奥地利部队,接管了莱茵兰的宪兵部队,建立了一些装甲师,并改组了战时后备军,使军队总数又上升到新的高度。1938年末的危机时期里,现役部队达到42个师,预备役部队8个师,战时后备军21个师;次年夏季,战争开始时,德国野战部队战斗序列已达103个师,一年内猛增了32个师。德国空军的扩充更是迅猛异常。1932年,德国年产飞机仅为36架,1934年和1936年分别上升到1938架和5112架;据1933年7月的指令称,全军种共有飞行中队26个,但到战争爆发时,已上升到302个中队,并在前线配有可供作战的飞机4000架。如果海军在规模上给人的印象不那么深刻的话,那在很大程度上是由于这样一个事实(提尔皮茨早已注意到这一事实):建立一支强大的舰队至少要花一二十年的时间。不过,到1939年,海军上将雷德尔指挥一群快速的现代化战舰时,海军人员数量已比1932年增加了4倍,比希特勒上台前扩大了11倍。德国在海、陆、空方面的重整军备计划旨在尽快改变力量对比。

While all this looked impressive from the outside, it was decidedly shaky within. The blows the German economy had received from the Versailles territorial arrangements, the great inflation of 1923, the payment of reparations, and the difficulty of reentering pre-1914 foreign markets meant that it was only in 1927– 1928 that Germany’s output equaled that achieved prior to the First World War. But this recovery was promptly ruined by the great economic crisis of the following few years, which hit Germany more severely than most other countries; by 1932, industrial production was only 58 percent that of 1928, exports and imports had been more than halved, the gross national product had fallen from 89 billion to 57 billion reichsmarks, and unemployment had swollen from 1. 4 to 5. 6 million people. 79 Much of Hitler’s early popularity stemmed from the fact that the widespread programs of roadbuilding, electrification, and industrial investment greatly reduced the unemployment totals even before conscription did the rest. 80 By 1936, however, the economic recovery was being increasingly affected by the fantastic expenditure upon armaments. In the short term, this spending was yet another quasi-Keynesian government boost to capital investment and industrial growth. In the medium, let alone the long, term, the economic consequences were frightening. Probably only the U. S. economy could, without major difficulty, have withstood the strain placed upon it by this level of arms spending; the German economy certainly could not.

表面上,所有这一切都给人以深刻的印象,但德国内部却发生了严重动摇。《凡尔赛和约》的领土划分对德国经济的打击,1923年严重的通货膨胀,战争赔偿以及难以重新进入1914年以前的国际市场等,这一切都意味着到1927~1928年,德国的总产量才达到第一次世界大战前的水平。但是,这次复苏很快又为随后几年的严重经济危机所破坏,那次危机使德国遭到了比其他国家更为沉重的打击。到1932年,其工业产量只占1928年的58%,进出口额只有1928年的一半多,国民生产总值从890亿帝国马克下降到570亿帝国马克,失业人数从140万增加到560万。希特勒早期所享有的声望主要是由于这样的事实,即在征兵解决一部分失业人口之前,大规模修路、电气化和工业投资计划极大地降低了失业人口的总数。然而,到1936年,经济复苏不断受到庞大的军备开支的影响。在短期里,这样的开支类似凯恩斯的由政府来促进资本投资和工业增长的办法;而在中期(暂且先不提长期),其经济上的各种后果是令人惊恐的。或许只有美国经济才不会有很大困难来承受这种军备开支水平所产生的压力,而德国经济当然是承受不住的。

The first serious problem, little perceived by foreign observers at the time, was the quite chaotic structure of National Socialist decisionmaking, something which Hitler seems to have encouraged in order to retain ultimate authority. Despite the pronouncements of the Four-Year Plan, there was no coherent national program to relate the arms buildup to Germany’s economic capacity and to allocate priorities between the services; Goering, nominally in charge of the plan, was a hopeless administrator. Instead, each branch pursued its own breakneck expansion, setting new (often preposterous) targets and then competing for the necessary allocations of capital investment and, especially, raw materials. To be sure, the situation would have been even more chaotic had the government not imposed strict controls upon labor, compelled private industry to reinvest its profits into manufactures approved of by the state and, through high taxation, deficit borrowing, checking wages and personal consumption, also forced an increasing amount of the national product into capital investment for the arms industry. But even when government expenditure soared to 33 percent of GNP by 1938 (and much “private” investment was by then really done at the state’s request), there were insufficient resources to meet the overlapping and sometimes megalomaniacal demands of the armed services. The ZPlan fleet being built for the German navy would have needed 6 million tons of fuel oil (equal to Germany’s entire consumption in 1938); the Luftwaffe’s plan to have 19,000 (!) front-line and reserve aircraft by 1942 would require “85 percent of the existing world production of oil. ”81 In the meantime, each service struggled to get a larger share of skilled manpower, steel, ball bearings, petroleum, and other vital strategic materials.

那时,外国观察家并未察觉到的首要的严重问题是,国家社会主义的决策机构处于极度混乱之中,其中某些事情似乎得到了希特勒的鼓励,以便保持最高权威。四年计划虽然公布了,但缺乏一个全国协调一致的方案,把扩充军备同德国经济的容量和三军建设项目的轻重缓急密切联系起来。戈林名义上负责这项计划,但实际做事只是个无能为力的行政官员。相反,每一个分支部门都在追求极端危险的自我扩展,制定新的(常常是荒谬的)目标,争夺资本投资尤其是原材料的必要分配。可以肯定,如果政府对劳动力不实行严格控制,不强迫私营工业将其利润再投资到国家批准的制造业中,不征收高税和赤字举债,不控制工资和个人消费,不把适当数量的国民生产品作为军事工业的资本投资的话,那么,形势就会变得更加混乱。1938年,甚至当政府开支上升到国民生产总值的33%时(在国家的要求下,而且大部分的“私人”投资当时确实尽了力),也没有足够的资源来满足军事部门重叠的有时是狂妄自大的要求。有关重建德国海军的“Z计划”需要600万吨燃油(等于1938年德国的总消耗量),空军计划到1942年要拥有1.9万架前线战斗机和备用飞机,此计划需要“当时世界原油产量的85%”!同时,每个军种都争先恐后地争夺大批训练有素的人员、钢材、滚珠轴承、石油和其他重要战略物资。

Finally, this frantic arms buildup clashed with Germany’s acute dependence upon imported raw materials. Rich only in coal, the Reich required vast amounts of iron ore, copper, bauxite, nickel, petroleum, rubber, and many other items upon which modern industry—and modern weapons systems—relied. 82 By contrast, the United States, the British Empire, and the Soviet Union were well endowed in all those respects. Before 1914, Germany had paid for such imports by its booming export of manufactures: in the 1930s, this was no longer possible, since German industry was now being redirected into the production of tanks, guns, and aircraft for the Wehrmacht’s consumption. Furthermore, the costs of the First World War and of later reparations, together with the collapse in the traditional export trades, had drained Germany of virtually all foreign currency; in 1938, it possessed only 1 percent of the world’s gold and financial reserves, compared with the United States’ 54 percent and France’s and Britain’s 11 percent each. 83 Hence the strict regime of currency controls, barter arrangements, and other special “deals” instituted by Reich agencies in order to pay for vital imports without transferring gold or currency. Hence, too, the much proclaimed efforts to escape from such dependence by the production of synthetic substitutes (oil, fertilizer, etc. ) under the Four-Year Plan. Each of these devices helped; none of them, or even all of them together, could balance the demands made by the arms buildup. This explains the recurrent crises within the German armaments industry, as the national stockpiles of raw materials were exhausted and funds ran out to pay for fresh supplies. In 1937, Raeder warned that the entire naval construction would have to be halted unless more materials were secured. And in January 1939, Hitler himself ordered massive reductions in allocations to the Wehrmacht of steel, copper, rubber, and other materials while the economy waged an “export battle” to raise foreign currency. 84

最后,大规模扩充军备与德国严重依赖进口原材料的情况大相径庭。这个帝国煤矿还算丰富,但却大量需要铁矿石、铜、铝、镍、石油、橡胶和其他物资,这些物资是现代工业——和现代武器系统——赖以生存的基础。相反,美国、英国和苏联的这些资源则十分丰富。1914年前,德国通过制造业产品的出口来支付上述物资的进口,但在30年代,这样做已经不再可能,因为德国工业都已转向为德国军队生产坦克、枪炮和飞机了。此外,第一次世界大战的开支、后来的战争赔偿以及传统出口行业的崩溃,实际已把德国所有的外汇储备消耗殆尽。1938年,德国仅占世界黄金和金融储备的1%,而美国却占了54%,法国和英国各占11%。因此,帝国各机构实行严格控制国家外汇的制度,进行以货易货以及其他特殊“交易”,以此来支付重要物资的进口,而不用黄金和外汇。在四年计划里,德国明确决定要通过生产合成代用品(石油、化肥等)来摆脱对那些急需物资的依赖。当然,每一种手段都是有效的,但没有一个手段,或即使所有的手段都加在一起,也不能满足扩充军备的需要。由于国家储备的原材料已经枯竭,为了支付新鲜的补给品,资金也使用殆尽,这就是德国军事工业反复发生危机的原因。1937年,雷德尔警告说,除非能够获得更多的原料,否则整个海军建设将不得不停止。1939年1月,希特勒亲自下命令,大量削减配给德国国防军的钢、铜、橡胶和其他物资,因为经济上正在打一场“出口仗”,以提高外汇储备。

There were three related consequences of the above for German power and policies. The first was that Germany was not as strong, militarily, by 1938–1939 as Hitler liked to boast and the western democracies feared. The field army, claiming a strength of 2. 75 million men at the outset of war, contained a small number of mobile, well-armed divisions and a very long tail of underequipped reserve divisions; experienced officers and NCOs were almost overwhelmed by the need to train such a mass of raw soldiery. Munitions stocks were slim. Even the famed panzer units had fewer tanks than the Anglo-French totals at the onset of hostilities. The navy, which was planning for a war in the mid-1940s, described itself as “completely inadequately armed for the great conflict with Britain”85—a fair summary in respect to surface warships, even if the U-boats were going to help redress the balance. As for the Luftwaffe, it was strong chiefly because its foes were so chronically weak—but it always suffered from a lack of reserves and supporting services. In the international crises of the late 1930s, it had never been as powerful as its opponents had imagined—and both its aircraft industry and its aircrews had found it very difficult to adjust to the “second generation” of planes. For example, the number of aircraft crews “fully operational” was far fewer than those defined as “front-line” during the Munich crisis—and the very idea of bombing London to a cinder was absurd. 86

上述情况对德国的国力和政策产生了三个相互关联的后果。第一个后果是,德国在军事上并不像希特勒在1938~1939年吹嘘的、使西方民主国家感到恐惧的那样强大。在战争开始时,野战陆军部队声称有275万人,但只有少量装备精良的机动师,为数众多的是装备低劣的预备役师,而且急需大批经验丰富的军官和士官来训练众多的新兵。军需品的储备少得可怜,甚至在与英国和法国发生敌对行动时,著名的德国坦克部队拥有的坦克数也比英法两国的坦克总数少。计划于40年代中期参战的海军自述说,“要同英国打大仗,装备根本不够格”——即使把潜水艇加进来弥补这一差距。就水面舰只来说,这也是一个公正的结论。至于空军,其力量是强大的,主要是因为它的敌人长期衰弱,但它也受尽了后备力量和后勤保障部队不足的折磨。在30年代末的国际危机中,德国绝没有其对手想象的那么强大——其航空工业和空勤人员要适应“第二代”飞机非常困难,例如,“能够熟练操作的”空勤人员人数远远不能满足慕尼黑危机时“前线”所规定的人数——把伦敦炸成一片灰烬的想法是荒唐的。

Still, it may be unwise to go all the way with recent revisionist literature about Germany’s unreadiness for war in 1939. At the end of the day, military effectiveness is relative. Few, if any, armed services claim that all their needs are satisfied; and the German weaknesses have to be measured against those of their foes. When that is done, the picture seems far more favorable to Berlin, especially because of the efficiency of its armed services in operational doctrine: its army was prepared to concentrate its tank forces, and then to allow them initiative on the battlefield, keeping in touch by radio; its air force, despite tendencies toward “strategic” missions, was trained to give assistance to the army’s thrusts; its U-boat arm, though small, was flexible as to tactics. All this was important compensation for, say, meager stocks of rubber. 87

完全赞同最近修正主义者的著作中关于1939年德国对战争毫无准备的说法是不明智的。归根到底,军事效力只是相对的。在武装部队中,很少有(即使有的话)部队会声称他们所有的需要都得到了满足。衡量德国的弱点必须同其敌人的弱点进行比较。经过比较之后,情况对柏林似乎非常有利,特别是由于其武装部队的效率一直处于这样一种作战思想指导之下——陆军准备集中坦克部队,并让其在战场上作为先导,通过无线电保持联系;空军尽管偏重于执行“战略”任务,但也接受了援助陆军突击的训练;潜艇部队尽管规模较小,但在战术上却是灵活多变的。所有这些,都是对橡胶储备不足(比如说)的重要补充。

This brings us to the second consequence. Because the German armed forces had rearmed so rapidly that they severely strained the economy, there was a massive temptation on Hitler’s part to resort to war in order to obviate such economic difficulties. As he well knew, the acquisition of Austria brought with it not only another five divisions of troops, some iron ore and oil fields, and a considerable metal industry, but also $200 million in gold and foreign-exchange reserves. 88 The Sudetenland was less useful economically (though it did have coal deposits), and by early 1939 the Reich’s foreign currency position was critical. It was scarcely surprising, therefore, that Hitler was greedily eyeing the rest of Czechoslovakia and rushed to Prague in March 1939 to examine the booty once the occupation occurred. Apart from the gold and currency assets held by the Czech national bank, the Germans also seized large stocks of ores and metals, which were swiftly used to aid German industry; while the large and profitable Czech arms industry could now be exploited to earn currency for Germany by selling (or bartering) its products to clients in the Balkans. The aircraft, tanks, and weapons of the substantial Czech army were also taken, partly to equip new German divisions, and partly to be sold for foreign currency. All this, together with Czechoslovakia’s industrial production, was a great boost to German power in Europe, and permitted Hitler’s hectic (if somewhat hand-to-mouth) rearmament program to continue—until the next crisis. As Tim Mason has pointed out, “the only ‘solution’ open to this regime of the structural tensions and crises produced by dictatorship and rearmament was more dictatorship and rearmament A war for the plunder of manpower and materials lay square in the dreadful logic of German economic development under National Socialism. ”89

这给我们带来了第二个后果:德国武装部队重新装备的速度太快,因而严重损伤了经济。对于希特勒来说,向他国诉诸武力以解决经济困境有极大的吸引力。他很清楚地知道,夺取奥地利不仅能给德国增加5个师的兵力,一些铁矿和油田,相当规模的金属工业,而且还能得到价值两亿美元的黄金和外汇储备。苏台德地区并无多大经济价值(尽管那里煤矿丰富),到1939年初,第三帝国的外汇形势岌岌可危,希特勒把贪婪的目光盯在捷克斯洛伐克的其余部分。1939年3月,德军冲向布拉格,一旦占领,马上开始清点战利品,所有这一切丝毫不会令人奇怪。德国人除了夺得捷克国家银行存有的黄金和外汇资产外,还夺得了大量的矿石和金属,这些东西很快就被用来帮助德国工业。同时,规模庞大和利润丰盈的捷克军事工业的产品,可以卖给巴尔干半岛的顾客来为德国赚取外汇(或交换其他物品)。捷克军队的飞机、坦克和武器也为德国人接收,一部分用来装备新建的德国师,另一部分被变卖以赚取外汇。所有这一切,再加上捷克斯洛伐克的工业生产,都极大地增强了德国在欧洲的力量,使希特勒狂热的(虽然多少有些勉强维持的)扩军计划得以继续进行下去,直到再次出现危机时为止。正如蒂姆·梅森所指出的:“公开解决这个由于独裁和重整军备而造成体制上紧张和危机的政权所面临的困难,其唯一的‘办法’就是加强独裁和重整军备……一场为夺取劳动力和原材料的战争,深深扎根于国家社会主义领导下的德国经济发展的恐怖逻辑中。”

The third consequence—and problem—was this: just how far could Germany maintain such a policy of conquest and plunder without overextending itself? Once the initial German rearmament was under way, and its armed services were equipped with modern weapons, the pattern of overcoming weak neighbors and gaining fresh territories, raw materials, and currency seemed self-fulfilling; by April/May 1939, it was clear that Poland was the next stage. But even if that country could be swiftly conquered, was Germany capable of facing France and Britain—that is, engaging in a war which would be much more challenging to a Greater German economy still heavily dependent upon imported raw materials? The evidence suggests that while he was willing to take the risk of fighting the western democracies in 1939, Hitler hoped that they would once again back down and allow him another limited war of plunder, against Poland alone; and this in turn would help the German economy to prepare its first Great Power war, somewhere in the mid-1940s. 90 Given the weakened economic and strategic power of France and Britain, and the hesitancy of their political leaderships by 1939, even a premature struggle with those powers may have seemed worth the risk—although if the military operations were stalemated on the lines of the 1914–1918 war, Germany’s initial lead in modern armaments would probably be slowly eroded. Victory for the Führer and his regime would, however, be much more problematical if the United States should lend its aid to the Allies; or if operations were extended into Russia, where the sheer size of the country implied lengthy, drawn-out fighting which placed a premium on economic stamina.

第三个后果和问题是:德国如不进行过分的扩张,它的征服和掠夺政策能维持多久?一旦德国重整军备的计划开始实行,其武装部队装备了现代化武器,那么攻克弱小邻国,攫取新的土地、原材料和外汇等似乎都会顺理成章地实现。1939年4至5月,波兰显然成为德国占领的下一个目标。但是,即使波兰能够很快被征服,德国能够对付得了法国和英国吗?就是说,同英法作战,对于仍然严重依赖进口原材料的德国的经济来说将是一个更大的挑战,它能承担得了吗?有证据表明,希特勒在1939年甘冒同西方民主国家开战的风险时,他希望这些国家能够再次让步,允许他再发动一次有限的掠夺战争,只对付波兰一国,这将有助于德国经济做好准备,以便德国于40年代中期在某一地区进行第一次大国战争。假定法国和英国的经济和战略力量虚弱,在1939年时这两个国家的政治领导人还在踌躇不定,那么德国冒险同这两国提前交战似乎是值得一试的——即使军事行动僵持在1914~1918年战争的战线上,但德国在现代军备上原有的领先地位可能会衰弱得慢一些。然而,如果美国给予盟国以援助,那么,元首及其政权的胜利将很难有望;或者,如果把军事行动扩展到苏联,那么,苏联广袤的国土意味着要打一场漫长的、胜负难分的并给经济带来沉重负担的战争。

On the other hand, since the Nazi regime lived upon conquest, and Hitler was driven forward from one acquisition to the next, how and where could a halt be called? The full logic of his megalomania implied that no other state should be a challenge to Germany in Europe, and possibly in the world. Only by this means would his foes be crushed, the “Jewish problem” solved, and the Thousand-Year Reich established on a firm footing. 91 Despite all the lines of continuity, the German Führer was quite different from his Frederickian and Bismarckian forebears in his fantastic schemes for world power and his ultimate disregard for all the obstacles which stood in the way of this design. Impelled as much by these manic, long-term ambitions as by the need to escape from short-term crises, Hitler, like the Japanese, was committed to altering the international order as soon as possible.

另一方面,由于纳粹政权靠征服为主,希特勒得陇望蜀,被一个接一个的虏获物驱使着,怎么可能会止步,何地是止境?他狂妄自大的逻辑意味着,在欧洲——可能的话,在整个世界上,任何国家都不该向德国挑战。只有靠这些手段,他的敌人才会被粉碎,“犹太人问题”解决了,千年帝国才会建立在坚实的基础上。尽管传统有延续性,但这位德国元首在他那荒唐怪诞的夺取世界霸权的计划以及极端无视实现这一计划所遇到的障碍等方面,同他的腓特烈式和俾斯麦式的祖先非常不同。在这种长期而疯狂的野心以及需要避免短期危机的愿望推动下,希特勒就像日本人一样,专心致志于尽可能及早地改变国际秩序。