The Offstage Superpowers

幕后超级大国

As noted above, one of the greatest difficulties which faced British and French decision-makers as they wrestled with the diplomatic and strategical challenges of the 1930s was the uncertainty which surrounded the stance of those two giant and somewhat detached Powers, Russia and the United States. Was it worth making further efforts to persuade them into an alliance against the fascist states, even if this involved substantial concessions to Moscow’s and Washington’s requirements, and provoked criticism at home? Which of these should be wooed more ardently, and in what respects? Would an open move, say, toward Russia merely provoke rather than deter a German or Japanese reaction? From the viewpoint of Berlin and Tokyo (less so of Rome), the attitude of Russia and the United States was equally important. Would these Powers remain aloof while Hitler reordered the boundaries of central Europe? How would they react to further Japanese expansion in China or operations against the old European empires in Southeast Asia? Would the United States give at least economic aid to the western democracies, as occurred between 1914 and 1917? And would the USSR be bought off, by economic and territorial deals? Finally, did those two enigmatic, introspective polities really matter? How strong were they, in fact? How important in the changing international order? It was harder to attempt an answer to such questions in the case of a

如前所述,当英国和法国的决策者们全力对付20世纪30年代外交和战略上的挑战时,他们所面临的一个最大困难是拿不准那两个像巨人一般但有些孤立的大国——苏联和美国所持的立场。是否值得做进一步的努力去说服这两个大国加入到反法西斯国家的联盟中来,甚至不惜对莫斯科和华盛顿的要求做出实质性的让步,并在国内遭到批评?应该更热情地从哪些方面拉拢哪一个大国?比如说,对苏联采取一些公开行动,会不会反而挑起而不是遏制德国或日本的回击?以柏林和东京的观点(先不提罗马)来看,苏联和美国所持的态度同等重要。当希特勒重新安排中欧的边界时,这两个大国将会漠然视之吗?对于日本在中国的进一步扩张,以及对老牌欧洲帝国在东南亚属地采取的军事行动,它们会做出何种反应呢?美国会像1914年至1917年时那样,至少为西方民主国家提供经济援助吗?可以用经济和领土交易收买苏联吗?最后,这两个诡秘多变、讳莫如深的大国确实那么至关重要吗?它们到底有多强大呢?在这个变化着的国际秩序中能发挥多大作用呢?

It was harder to attempt an answer to such questions in the case of a “closed” society like the Soviet Union. Nonetheless the outlines of Soviet economic growth and military power in that era now seem evident. The first and most obvious point was that Russia had been dreadfully reduced in strength, more than any of the other Great Powers, by the 1914–1918 conflict and then by the revolution and civil war. Its population had plummeted from 171 million in 1914 to 132 million in 1921. The loss of Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states removed many of the country’s industrial plants, railways, and farms, and the prolonged fighting destroyed much that remained. The stupendous decline in manufacturing—down to 13 percent of its 1913 output by 1920—concealed the even greater collapse of certain key commodities: “thus only 1. 6 percent of the prewar iron ore was being produced, 2. 4 percent of the pig iron, 4. 0 percent of the steel, and 5 percent of the cotton. ”126 Foreign trade had disappeared altogether, the gross yield of crops was less than half the prewar figure, and per capita national income declined by more than 60 percent to a truly horrendous level. However, since the extreme severity of these falls was chiefly caused by the social and political chaos of the years 1917–1921, it followed that the establishment of Soviet rule (or indeed any rule) was bound to effect a recovery of sorts. The prewar and wartime development of Russian industry had bequeathed to the Bolsheviks an array of factories, railway works, and steel mills. There was a basic infrastructure of railways, roads, and telegraph lines. There were industrial workers who could return to the factories once the civil war was over. And there was an established pattern of agricultural production, and the sale of foodstuffs to the towns and cities, which could be restored once Lenin had decided (under the New Economic Policy of 1921) to abandon the fruitless attempts to “communize” the peasantry and instead to permit individual farming. By 1926, therefore, agricultural output had returned to its prewar level, followed two years later by industrial output. The war and revolution had cost Russia thirteen years of economic growth, but it now stood ready to resume its upward surge.

就苏联这样一个“封闭”的社会来说,试图回答这些问题是很困难的。然而,这一时期苏联经济增长和军事力量的大致轮廓还是清楚的。最为明显的一点是,苏联的力量由于第一次世界大战,以及随后的革命和内战而严重削弱,其程度超过其他任何大国。苏联人口从1914年的1.71亿骤然下降至1921年的1.32亿。由于丧失波兰、芬兰和波罗的海沿岸国家,它丢掉了许多工厂、铁路和农场,余下的部分也大都遭到长期战争的破坏。制造业下降惊人,1920年下降到1913年的13%——掩盖了某些主要商品甚至更为严重的崩溃:“铁矿石产量仅为战前的1.6%,生铁为2.4%,钢为4%,棉花为5%。”外贸全部中止,粮食总产量还不及战前的一半,人均国民收入下降了60%,达到一种着实令人震惊的地步。然而,由于这些极端严重的下降主要是由1917~1921年的社会和政治动荡造成的,因此可以说,苏维埃政权(实际上无论何种统治)的建立肯定有助于各种生产的恢复。战前和战时发展起来的沙俄工业给布尔什维克留下了一大批工厂、铁路和钢厂。铁路、公路和电报线路已初具规模。内战一结束,产业工人就可以返回工厂;农业生产已有固定模式和向城市出售粮食的传统,一旦列宁决定(根据1921年新经济政策)放弃农民“共产化”的徒劳无益的努力,转而允许建立私人农场,农业就可以恢复。因此,到1926午时,农业产量回升到战前的水平;两年后,工业产量也达到了战前水平。战争和革命使俄国的经济发展延误了长达30年的时间,但其经济已做好了恢复上涨的准备。

But that “surge” was unlikely to be swift enough—certainly not to the increasingly autocratic Stalin—while Russia labored under its traditional economic weaknesses. With no foreign investment available, capital had somehow to be raised from domestic sources to finance the development of large-scale industry and the creation of substantial armed forces in a hostile world. Given the elimination of a middle class, which could either have been encouraged to create capital or plundered for its existing wealth; given, too, the fact that 78 percent of Russian population (1926) remained in a bottom-heavy agricultural sector, which was still overwhelmingly in private hands, there seemed to Stalin only one way for the state to raise money and simultaneously increase the switch from farming to industry: that is, by the collectivization of agriculture, forcing the peasants into communes, destroying the kulaks, controlling the output from the land, and fixing both the wages paid to farm workers and the (far higher) prices of food for resale. In a frighteningly draconian way, the state thus interposed itself between rural producers and urban consumers, and extracted money from each to a degree that the czarist regime had never dared to do. This was accentuated by the deliberate price inflation, a variety of taxes and dues, and the pressures to show one’s loyalty by buying state bonds. The overall result, represented in the crude macroeconomic statistics, was that the share of Russian GNP devoted to private consumption, which in other countries going through the “takeoff” to industrialization was around 80 percent, was driven down to the appalling level of 51 or 52 percent. 127

但当苏联在虚弱的传统经济下迈着沉重的脚步时,“上涨”不可能立竿见影——当然,不是因为斯大林专制的加强。由于没有外国投资,所以不得不靠国内筹集资金,以支持庞大工业的发展,同时在充满敌意的世界中建立一支庞大的军队。既然消灭了资产阶级,既然78%的俄国人口(1926年)仍然从事占国民经济大头的农业生产,而农业的绝大部分又掌握在私人手里,那么在斯大林看来,为国家集资以及加速实现农业向工业转化,唯一的出路就是实行农业集体化,强迫农民加入公社,消灭富农,控制农产品产量,规定农场工人的工资和转卖粮食的价格(后者比前者高得多)。国家置身于农村生产者和城市消费者之间,采取令人惊愕的严酷方法从两方面拼命积累资金。人为的价格飞涨,各类的捐税,人们迫于各种压力通过购买国债券来表现自己的忠诚,这一切促使国内局势更为紧张。宏观经济的粗略统计表明,总的结果是,苏联用于个人消费的支出占国民生产总值的51%或52%(这一水平低得令人难以置信),而其他国家除去进行工业化所需份额外,剩下用于个人消费的份额大约是80%。

There were two contrary, yet predictable economic consequences from this extraordinary attempt at a socialist “command economy. ” The first was the catastrophic decline in Soviet agricultural production, as kulaks (and others) resisted the forced collectivization and then were eliminated. The horrific preemptive slaughter of farm animals—“the number of horses fell from 33. 5 million in 1928 to 16. 6 million in 1935; and the number of cattle from 70. 5 to 38. 4 million”128—in turn produced a staggering decline in meat and grain outputs and in an already miserable standard of living, not to be recovered until Khrushchev’s time. Esoteric calculations have been attempted as to the proportion of the national income which was later returned to agriculture in the form of tractors or electrification—as opposed to the amount siphoned off by collectivization and price controls129—but this is an arcane exercise for our purposes, since (for example) tractor factories, once established, were designed to be converted to the production of light tanks; peasants, of course, were not so useful in checking the Wehrmacht. What was incontrovertible was that for the moment, Soviet agricultural output collapsed. The casualties, especially during the 1933 famine, could be reckoned in millions of lives. When output began to recover in the late 1930s, it was expedited by hundreds of thousands of tractors, hordes of agricultural scientists, and armies of tightly controlled collectives. But the cost, in human terms, was immeasurable.

苏联在社会主义计划经济中所做的极端性努力产生了两个相反的但可以预见的经济后果。第一个后果是,由于富农反对强制的集体化,随后遭到灭顶之灾,因而苏联的农业生产出现灾难性的崩溃。农场牲口过早地遭到惊人的屠宰——马匹从1928年的3350万匹减少到1935年的1660万匹;牛从7050万头减少到3840万头,因而造成了肉和粮食产量的锐减,使本来极端贫困的生活水平急速下降,直到赫鲁晓夫时期才得到恢复。有人曾试图对国民收入中后来以拖拉机或电气化形式偿还给农业的那一部分,与通过集体化以及价格控制所刮取的那一部分进行秘密计算,但对我们的目的来说,这只是一种神秘的运用,因为(比如说)拖拉机工厂建立以后,可以用来生产轻型坦克。当然,农民在阻止德军进攻方面是不起多大作用的。毋庸置疑的是,苏联的农业生产这时土崩瓦解了。特别是1933年的饥荒,夺走了几百万人的生命。20世纪30年代末,农业生产得以恢复,这是投入几十万台拖拉机、大批农业科学家和严格控制的集体农民大军迅速努力的结果。但是,就人力来说,代价是无法估量的。

The second consequence was altogether brighter, at least for the purposes of Soviet economic-military power. Having driven private consumption’s share of the GNP down to a level probably unmatched in modern history—and certainly far lower than, say, the Nazis could ever contemplate in Germany—the USSR was able to deploy the fantastic proportion of around 25 percent of GNP for industrial investment and still possess considerable sums for education, science, and the armed services. While the workplace of much of the Russian people was being transformed at a staggering rate, with the number employed in agriculture dropping from 71 percent to 51 percent in the twelve years 1928–1940, that population was also being educated at an unprecedented pace. This was vital at two levels, since Russia had always suffered—in comparison, say, with Germany or the United States—from having a poorly trained and illiterate industrial work force, and in possessing only a minuscule number of engineers, scientists, and managers necessary for the higher direction and steady improvement of the manufacturing sector. With millions of workers now being trained, either in factory schools or in technical colleges, and then (slightly later) with a vast expansion in university numbers, the country was at last acquiring the trained cadres necessary for sustained growth; the number of graduate engineers in the “national economy” rose, for example, from 47,000 in 1928 to 289,900 in 1941. 130 Many of the figures touted by Soviet propagandists in this period were doubtless inflated and concealed various weak points, but the deliberate allocation of resources to growth was unquestionable. So, too, was the creation of enormous new power plants, steelworks, and factories beyond the Urals, invulnerable to attack from either the West or Japan.

第二个后果更清楚一些,至少从苏联的经济军事力量来看是这样。由于个人消费在国民生产总值中所占份额被压低到也许是现代史上最低的水平——肯定比纳粹分子曾期望在德国达到的低得多,苏联得以把国民生产总值的大约25%用于工业投资,同时还拥有一大笔资金用于教育、科学和军队。大批俄国人的工作岗位以惊人的速度发生了转化,在1928~1940年的12年间,农业人口从71%急剧下降到51%,这部分人口也以一种前所未有的速度接受着教育。这点在两个层次上都非常重要,因为同德国或美国相比,苏联的工业劳动力缺乏训练,文化不高,同时仅有很少一批为制造部门进行高级指导和稳步经营所必需的工程师、科学家和管理人员,这就使俄国经常大吃苦头。现在,几百万工人在工厂的学校或技术学校里接受培训,稍后,大学数量又猛增,因而国家最终获得了维持经济增长所需要的受过培训的骨干。例如,在“国民经济”部门中,毕业的工程师数量从1928年的4.7万名上升到1941年的28.99万名。这一时期,苏联宣传人员所吹嘘的数字无疑是被夸大了,并且掩盖了各种薄弱环节,但在资源分配上有意识地保证经济增长是毋庸置疑的。同样,在乌拉尔山脉以东建立大规模的新发电厂、钢厂和其他工厂(这些工厂不会受到西方和日本的打击),也是毋庸置疑的。

The resulting upturn in manufacturing output and national income—even if one accepts the more cautious estimates—was something unprecedented in the history of industrialization. Because the actual volume and value of output in earlier years (e. g. , 1913, let alone 1920) was so low, the percentage changes are almost meaningless—even if Table 28 above serves the useful point of showing how the USSR’s manufacturing production was expanding during the Great Depression. However, if one examines only the period of the two Five-Year Plans (1928 to 1937), Russian national income rose from 24. 4 to 96. 3 billion rubles, coal output increased from 35. 4 to 128 million tons and steel production from 4 to 17. 7 million tons, electricity output rose sevenfold, machine-tool figures over twentyfold, and tractors nearly fortyfold. 131 By the late 1930s, indeed, Russia’s industrial output had not only soared well past that of France, Japan, and Italy but had probably overtaken Britain’s as well. 132

由此导致的苏联制造业产量和国民收入的增长——即使按照较为保守的估计,在工业化的历史上也可说是史无前例的。在最初几年里(如1913年,更不要说1920年),由于产量的实际数和价值都相当低,因此百分比的变化几乎毫无意义,尽管表28有助于说明大萧条时期苏联制造业生产是如何扩大的。不过,如果考察一下两个五年计划(1928~1937)就会发现,俄国的国民收入从244亿卢布提高到963亿卢布,煤产量从3540万吨提高到1.28亿吨,钢产量从400万吨增至1770万吨,电力增长7倍,机床增产20倍以上,拖拉机产量几乎增加40倍。事实上,到30年代末,俄国的工业总产量不仅超过了法国、日本和意大利,而且可能超过了英国。

Behind this impressive buildup, however, there still lurked many deficiencies. Although farm output slowly rose in the mid-1930s, Russian agriculture was now less capable than before of feeding the nation, let alone producing a surplus for export; and the yields per acre were still appallingly low. Despite fresh investment in railways, the communications system remained primitive and inadequate for the country’s growing needs. In many industries there was a heavy dependence upon foreign firms and foreign expertise, especially from the United States. The “gigantism” of the plants and of the entire manufacturing processes made difficult any swift adjustments of the product mix or the introduction of new designs. There were inevitable bottlenecks, too, because the planned expansion of certain industries did not match the existing stocks of raw materials or skilled manpower. After 1937, the reorientation of the Soviet economy toward a massive armament program was bound to affect industrial continuity and to distort the earlier planning. Above all, there were the great purges. Whatever the reasons for Stalin’s manic, paranoid assault upon so many of his own people, the economic results were serious: “civil servants, managers, technicians, statisticians, even foremen”133 were swept away into the camps, making Russia’s shortage of trained personnel more acute than ever. While the terror no doubt drove many to demonstrate a Stakhanovite loyalty to the system, it also greatly inhibited innovation, experimentation, open discussion, and constructive criticism: “the simplest thing to do was to avoid responsibility, to seek approval from one’s superior for any act, to obey mechanically any order received, regardless of local conditions. ”134 It saved one’s skin; but it did not help the growth of a complex economy.

然而,在这些给人以深刻印象的数字背后,仍然潜伏着许多不足之处。尽管农业总产量在30年代中期已开始缓慢增长,但俄国的农业比起以前来更没有能力供养整个国家,也谈不上生产剩余粮食用来出口,每英亩的产量仍然少得可怜。尽管对铁路增加了投资,但交通系统仍然很落后,不能满足国家经济发展的需要。很多工业严重依赖外国公司和技术,特别是美国的公司和技术。由于工厂和整个生产程序规模“巨型化”,因此很难迅速调整产品结构和引进新设计。某些工业有计划的扩充与原材料或技术力量的储备脱节,因而不可避免地造成卡壳现象。1937年以后,苏联经济转向大规模备战,这使工业的连续性受到影响,并且打乱了原先的计划。最重要的是大清洗运动——斯大林向如此众多的自己人发动了疯狂进攻,无论他有什么理由,给经济带来的后果都是严重的。“政府官员、管理人员、技术员、统计员甚至一般的工长”都被清扫进集中营,这使俄国严重缺乏技术人员的形势变得更为严峻。恐怖无疑驱使许多人对现制度表示斯达汉诺夫式的忠诚,但同时也严重压抑了创新、实验、公开讨论和建设性的批评。“最省事的做法就是逃避责任,事无大小都寻求上司的批准,不顾实际情况而机械地服从上级命令。”这样做倒是可以苟且偷生,但对发展综合经济却无任何帮助。

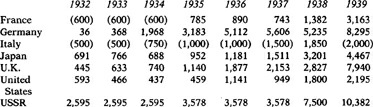

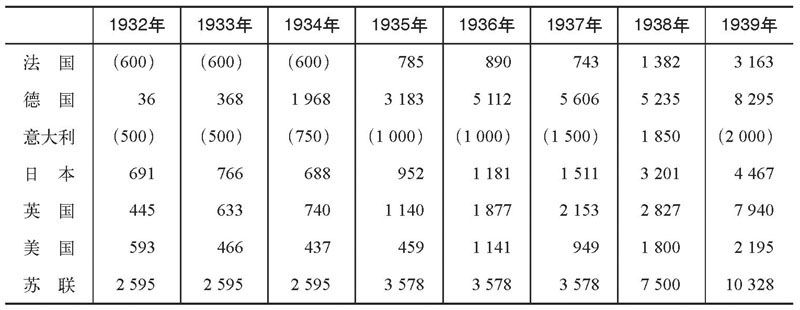

Having been born out of a war, and feeling acutely threatened by potential enemies—Poland, Japan, Britain—the USSR devoted a large share of the state budget (12–16 percent) to defense expenditures for much of the 1920s. That share fell away during the early years of the first Five-Year Plan, by which time the regular Soviet armed forces had settled down to about 600,000 men, backed by a large but inefficient militia twice that size. The Manchurian crisis and Hitler’s accession to power led to swift increases in the size of the army, to 940,000 in 1934 and 1. 3 million in 1935. With the rise in industrial output and national income deriving from the Five-Year Plans, large numbers of tanks and aircraft were built. Innovative officers around Tukhachevsky were willing to study (if not fully accept) ideas from Douhet, Fuller, Liddell Hart, Guderian, and other western theorists of warfare, and by the early 1930s the USSR possessed not only a tank army but also a large paratroop force. While the Soviet navy remained small and ineffective, a large aircraft industry was created in the late 1920s, which for a while produced more planes each year than all the other powers combined (see Table 29).

由于受过战争的洗礼,苏联对来自波兰、日本和英国这些潜在敌人的威胁特别敏感。因此,苏联在20世纪20年代里把国家预算的大部分(12%~16%)用于国防开支。在第一个五年计划的最初几年里,国防开支所占的份额缩小了,当时苏联的正规军下降到60万人左右,以两倍于正规军的庞大但效率低的民兵力量作为后盾。中国东北危机的爆发和希特勒的上台,促使苏联部队数量飞速增长,到1934年时达到94万人,1935年达到了130万人。随着几个五年计划的实施,工业总产量和国民收入增加,大批坦克和飞机制造出来。在图哈切夫斯基周围有一批富有革新精神的军官,他们愿意研究(如果说不是完全接受的话)杜黑、富勒、利德尔·哈特、古德里安以及其他西方军事理论家的思想。到30年代初,苏联不仅拥有一支坦克部队,还有一支庞大的伞兵部队。20年代末,虽然苏联海军力量仍然弱小,缺乏战斗力,但创建了规模巨大的航空工业,它每年所生产的飞机一度超过其他大国生产的总和(见表29)。

Table 29. Aircraft Production of the Powers, 1932–1939135

表29 1932~1939年各大国飞机产量

But these figures, too, concealed alarming weaknesses. The predictable corollary of Russian “gigantism” was an excessive emphasis upon quantity. Given the attributes of a command economy, this had resulted in the production of enormous numbers of aircraft and tanks by the early 1930s; by 1932, indeed, the USSR was producing over 3,000 tanks and over 2,500 aircraft—fantastically more than any other country in the world. Given the tremendous growth of the regular army after 1934, it must have been extraordinarily difficult to find sufficient highly trained officers and NCOs to supervise the tank battalions and air squadrons. It was even more difficult, in a country with a surplus of peasants and desperately short of skilled workers, to man a modern army and air force; despite the massive educational program, the country’s chief weakness in the 1930s probably still lay in the poor training of many of its workers and soldiers. Furthermore, Russia, like France, was a victim of heavy investment in aircraft and tank types of the early 1930s. When the Spanish Civil War showed the limits, in speed, maneuverability, range, and toughness, of these first-generation weapons, the race to build faster aircraft and more powerful tanks was accelerated. But the Soviet arms industry, like a large vessel at sea, could not change course swiftly; and it seemed folly to stop production on existing types while newer models were being built and tested. (In this connection, it is interesting to note that “of the 24,000 Russian tanks operational in June 1941, only 967 were of a new design equivalent or superior to the German tanks of that time. ”)136 On top of this, there came the purges. The decapitation of the Red Army—90 percent of all generals and 80 percent of all colonels suffered in Stalin’s manic drive—not only had the overall effect of destroying so many trained officers, but had specific results which badly hurt the armed forces. By wiping out Tukhachevsky and the “modern warfare” enthusiasts, by eliminating those who studied German methods and British theories, the purges left the army in the hands of such politically safe but intellectually retarded figures as Voroshilov and Kuluk. One early result was the disbanding of the seven mechanized corps, a decision influenced by the argument that the Spanish Civil War had shown that tank formations could play no independent offensive role on the battlefield and that the vehicles should be distributed to rifle battalions in order to support the infantry. In much the same way it was decided that the TB-3 strategic bombers were of little use to the USSR.

但是,这些数字也掩盖了许多令人吃惊的弱点。苏联“巨型化”的必然后果是过分强调数量。由于计划经济的特点,20世纪30年代初期苏联生产了大批飞机和坦克。例如,1932年,苏联生产了3000多辆坦克和2500多架飞机——比世界上任何一个国家都多。然而由于1934年后正规部队的急剧膨胀,要获得足够的受过高级训练的军官和士官来管理坦克营和航空兵中队,是极其困难的。在这个农民过剩、熟练工人严重缺乏的国家里,要装备一支现代化部队和空军就更困难了。尽管有宏大的教育计划,但30年代这个国家的主要弱点仍然在于大批工人和士兵训练不足。尤其是,苏联跟法国一样,它是对30年代初期的各种飞机和坦克型号进行巨大投资的牺牲者。当西班牙内战暴露出第一代此类武器在速度、机动性、航程和耐强度方面的局限性时,各国加快了制造速度更快、威力更大的飞机和坦克的竞赛。但苏联的军事工业就像大海中的一艘巨轮,不能立即改变自己的航向;而且在试制新型飞机、坦克的同时,停止生产已有的各种型号似乎是愚蠢的(关于这点,非常有趣的是,1941年6月,在2.4万辆服役的坦克中,同德国坦克具有同等水平或超过德国水平的新式坦克只有967辆)。此外,还有大清洗运动。苏联红军军官被大批革职——90%的将军和80%的校级军官遭到斯大林所发动的疯狂运动的迫害——这不仅关系到杀害许多受过训练的军官所造成的普遍影响,而且对军队造成了严重的特殊后果。通过清除图哈切夫斯基和“现代战争”的热心者,消灭那些研究德国作战方法和英国军事理论的人,一些政治上可靠但智力迟钝的人,如伏罗希洛夫和库鲁克掌握了军队。早期的一个结果是解散了7个机械化军。做出这一决定的理由是西班牙内战显示出坦克编队在战场上不能发挥独立的进攻作用,这种武器应该分配给步兵营,以加强步兵的战斗力。出于同样的推理方式,他们认为TB-3重型轰炸机对苏联来说没有什么用处。

With much of its air force obsolescent and its armored units disbanded, with the services cowed into blind obedience by the purges, Russia was much weaker at the end of the 1930s than it had been five or ten years earlier—and in the meantime both Germany and Japan had greatly increased their arms output and were becoming more aggressive. The post-1937 Five-Year Plan clearly involved an enormous arms buildup, equal to and in many areas—e. g. , aircraft production— larger than Germany’s own. But until that investment had translated itself into far larger and better-equipped armed forces, Stalin felt Russia to be passing through a “danger zone” at least as threatening as the years 1919–1922. These external circumstances help explain the various changes in Soviet diplomacy during the 1930s. Worried by the Japanese aggression in Manchuria and perhaps even more by Hitler’s Germany, Stalin faced the prospect of a potential two-front war in theaters thousands of miles apart (exactly the strategical dilemma which paralyzed British decision-makers). Yet his diplomatic tacking toward the West, which included Russia’s 1934 entry into the League of Nations and the 1935 treaties with France and Czechoslovakia, did not bring the desired increase in collective security. Without a Polish agreement, there was really little Russia could do to aid France or Czechoslovakia—and vice versa. And the British frowned at these efforts to create a diplomatic “popular front” against Germany, which in part explains Stalin’s caution during the Spanish Civil War; a triumphant socialist republic in Spain, Moscow feared, might drive Britain and France to the right, as well as embroil Russia in open conflict with Franco’s supporters, Italy and Germany.

由于大批空军已经落后,装甲部队被解散,各军种出于对清洗的恐惧而对上级盲目服从,因此,苏联在30年代末期比5年前甚至10年前虚弱得多,而在同时,德国和日本却已大大地提高了武器生产量,变得更富有挑衅性。1937年后,苏联的五年计划明显涉及到大量的军备建设,其数量与德国相等,而在很多领域里,如飞机生产,其数量则超过德国。因为斯大林感到苏联正在通过“一个危险的区域”,至少同1919~1922年期间所受到的威胁一样,到这时,苏联的投资才转到建立一支规模庞大、装备优良的部队上来。这些外在的情况有助于说明20世纪30年代苏联外交政策的各种变化。斯大林对日本在中国东北的侵入感到忧虑,但更担心希特勒统治下的德国,因为他面临着在两个相距几千英里的战场上同时作战的前景(确切地说,这也是英国决策者感到束手无策的战略困境)。斯大林仍然把其外交政策的重点放在欧洲,这包括1934年苏联加入国际联盟,1935年分别与法国或捷克斯洛伐克签订条约,但这一切并没有使斯大林所期望的共同安全得到加强。实际上没有波兰的同意,苏联很难援助法国或捷克斯洛伐克;反过来,法国或捷克要是没有波兰的同意,同样也不能援助苏联。英国人对这些为建立一个反对德国的外交“统一战线”所做的努力表示不满,这也从一个方面说明了为何斯大林在西班牙内战期间表现得小心谨慎。莫斯科害怕,如果一个社会主义共和国在西班牙诞生,就有可能迫使英国和法国“向右转”,同时,苏联也将卷入同佛朗哥的支持者——意大利和德国的公开冲突中。

By 1938–1939, the external situation must have appeared more threatening than ever in Stalin’s eyes (which makes his purges even more foolish and inexplicable). The Munich settlement not only seemed to confirm Hitler’s ambitions in east-central Europe but—more worryingly—revealed that the West was not prepared to oppose them and might indeed prefer to divert German energies farther eastward. Since these two years also saw substantial border clashes between Soviet and Japanese armies in the Far East (necessitating the heavy reinforcement of the Russian divisions in Siberia), it was not surprising that Stalin, too, decided to follow an “appeasement” policy toward Berlin even if that meant sitting down with his ideological foe. Given the USSR’s own political ambitions in eastern Europe, Moscow had far fewer reservations about a carving up of the independent states in that region, provided that its own share was substantial. The surprise Nazi-Soviet pact of August 1939 at least provided Russia with a buffer zone on its western border and more time for rearmament while the West fought Germany in consequence of Hitler’s attack upon Poland. Feeding morsels to the crocodile (to use Churchill’s phrase) seemed much better than being devoured by it. 137

1938年至1939年,在斯大林眼里,外部局势变得更加危险(这使他的清洗也变得更加愚蠢,更加不可思议)。《慕尼黑协定》不仅证实了希特勒对中欧东部所怀有的野心,而且更令人不安的是,它还表明了西方不准备反对这样的野心,并且确实愿意把德国的力量转移到东面更远的地方去。由于1938~1939年苏联和日本在远东发生了严重的边界冲突(苏联有必要大力增强西伯利亚部队的力量),因此,斯大林也决定对柏林实行绥靖政策,即使这意味着同他的意识形态上的敌人坐下来谈判,也是不足为怪的。如果苏联对东欧存有政治野心,如果它认为自己在那里能获得丰盈的份额,那么莫斯科对瓜分这一地区的独立国家不会有很多保留意见。当西方正由于希特勒进攻波兰而与德国处于交战状态时,1939年8月,苏联与德国签订了举世震惊的《苏德互不侵犯条约》,这一条约至少为苏联在西部边界上提供了一个缓冲地带,并为苏联扩军备战赢得了更多时间。用丘吉尔的话说,以美食喂鳄鱼比葬身鳄鱼之腹好得多。

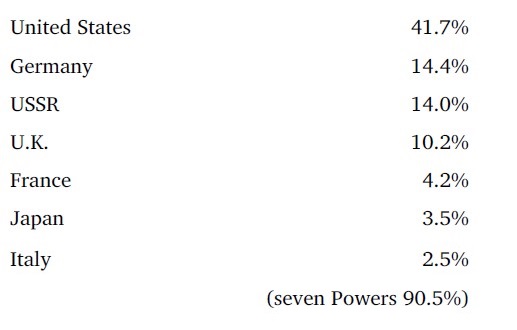

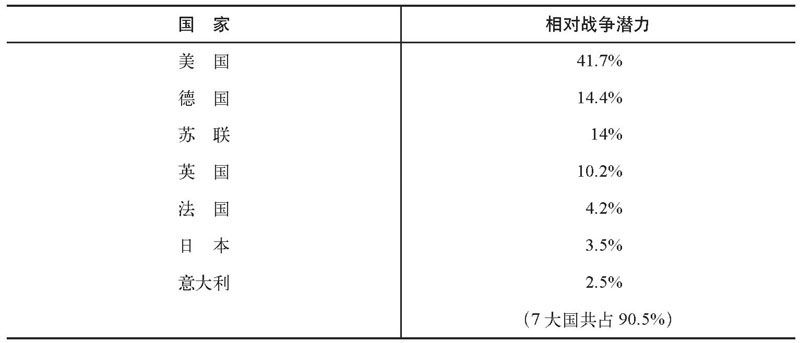

All this makes it inordinately difficult to measure Soviet power by the end of the 1930s, especially since statistics on “relative war potentials”138 reflect neither internal morale nor quality of armed forces nor geographical position. Clearly, the Red Army no longer resembled that “formidable modern force of great weight with advanced equipment and exceptionally tough fighting men” (except in the latter respect) which Mackintosh described the 1936 army as being;139 but how far it had lost ground was not clear. The 1939–1940 “Winter War” against Finland appeared to confirm its precipitous decline, yet the less-well-known 1939 clashes with Japan at Nomonhan showed a cleverly led, modern force in action. 140 It is also evident that Stalin was aghast at the devastating Blitzkrieg-style victories of the German army in 1940, and more than ever anxious not to provoke Hitler into a war. His other great and obvious worry was where Tokyo would decide to strike in the East —not that Japan was so mortal a foe, but the defense of Siberia was logistically very exhausting and would further weaken Russia’s capacity against the German threat. The swift recall of Zhukov’s armor, to join in the invasion of eastern Poland in September 1939, once a border truce in the east had been arranged with Japan, was illustrative of this precarious strategical juggling act. 141 On the other hand, by that time the damage inflicted upon the Red Army was being hastily repaired and its numbers increased (to 4,320,000 men by 1941), the entire Soviet economy was being deployed toward war production, massive new factories were being built in central Russia, and improved aircraft and tanks (including the formidable T-34) were being tested. The 16. 5 percent of the budget allocated to defense spending in 1937 had jumped to 32. 6 percent in 1940. 142 Like most of the other Great Powers in this period, therefore, the USSR was racing against time. More even than in 1931, Stalin needed to urge his fellow countrymen to close the productive gap with the West. “To slacken the tempo would mean falling behind. And those who fall behind get beaten” The Russia of the czars had suffered “continual beatings” because it had fallen behind in industrial productivity and military strength. 143 Under its even more autocratic and ruthless leader, the Soviet regime was determined to catch up fast. Whether Hitler would let it do so was impossible to say.

这一切都使得要衡量30年代末期苏联的力量极其困难,特别是“相对的战争潜能”的统计既没有反映出内部的士气,也没有反映出武装部队的质量以及地理位置。显然,苏联红军不再是“武器装备精良,战斗人员顽强,令人望而生畏,而且具有强大打击力的现代化部队”(“战斗人员顽强”这方面还没有变)。这是麦金托什在描述1936年部队的情况时说的。但苏军的基础在多大程度上受到削弱这一点仍不太清楚。1939~1940年苏联同芬兰发生的“冬战”证实,苏军的力量是急剧下降了,然而,1939年苏联在同日本于诺门罕发生的多次不太引人注目的冲突中,却展现了苏军是一支在战斗中指挥机智的现代化部队。斯大林为1940年德国以毁灭性的“闪电战”取得的胜利感到惊骇,因而更加迫切希望避免激怒希特勒发动战争,这点也是显而易见的。斯大林深为不安的另一个忧虑是,东京决定在远东的什么地方发动攻击——尽管日本并不是个不共戴天的敌人,但按照逻辑推理,西伯利亚虚弱的防务会进一步削弱苏联抵御德国威胁的能力。与日本签订了东部边界的停战协定后,朱可夫的装甲部队立即被召回,以参加1939年9月入侵波兰的行动,这是一个危险的战略性欺骗的例证。另一方面,到这时,苏联红军所遭受的损失已得到迅速弥补,部队人数增加了(1941年时已达到432万人)。苏联的整个经济正在为战争的到来进行调整,苏联中部正在建造大批新工厂,经过改装的飞机和坦克(包括难以对付的T-34型坦克)正在试验之中。1937年,苏联国防开支占财政预算的16.5%,1940年猛增到32.6%。同所有其他大国一样,苏联此时正在与时间赛跑。斯大林比1931年时更迫切地敦促他的人民缩小与西方在生产力方面的差距。“放慢速度即意味着落后,落后就要挨打……”,沙皇时期的俄国“一直处于挨打的局面”,原因就在于其生产和军事力量落后于西方。苏联政权在更为独裁和无情的领导人的领导下决定迎头赶上。希特勒是否会让苏联如愿以偿还是很难说的。

The relative power of the United States in world affairs during the interwar years was, curiously, in inverse ratio to that of both the USSR and Germany. That is to say, it was inordinately strong in the 1920s, but then declined more than any other of the Great Powers during the depressed 1930s, recovering only (and partially) at the very end of this period. The reason for its preeminence in the first of these decades has been made clear above. The United States was the only major country, apart from Japan, to benefit from the Great War. It became the world’s greatest financial and creditor nation, in addition to its already being the largest producer of manufactures and foodstuffs. It had by far the largest stocks of gold. It had a domestic market so extensive that massive economies of scale could be practiced by giant firms and distributors, especially in the booming automobile industry. Its high standard of living and its ready availability of investment capital interacted in a mutually beneficial fashion to spur on further heavy investments in manufacturing industry, since consumer demand could absorb virtually all of the goods which increased productivity offered. In 1929, for example, the United States produced over 4. 5 million motor vehicles, compared with France’s 211,000, Britain’s 182,000, and Germany’s 117,000. 144 It was hardly surprising that there were fantastic leaps in the import of rubber, tin, petroleum, and other raw materials to feed this manufacturing boom; but exports, especially of cars, agricultural machinery, office equipment, and similar wares, also expanded throughout the 1920s, the entire process being aided by the swift growth of American overseas investments. 145 Yet even if this is well known, it still remains staggering to note that the United States in those years was producing “a larger output than that of the other six Great Powers taken together” and that “her overwhelming productive strength was further underlined by the fact that the gross value of manufactures produced per head of population in the United States was nearly twice as high as in Great Britain or Germany, and more than ten to eleven times as high as in the USSR or Italy. ”146

令人奇怪的是,在两次世界大战之间,美国在国际事务中的相对力量与苏联和德国成反比。也就是说,美国在20世纪20年代的力量异常强大,但在30年代的萧条时期里,美国也比其他任何大国衰弱得更快,直到30年代末期才开始复苏(而且是部分地)。美国在过去几十年里处于突出地位的原因前面已做了清晰的论述。除日本外,美国是唯一从第一次世界大战中捞到好处的大国。美国除了已成为世界上最大的制造业和粮食生产国外,还是世界上最大的金融和债权国家,拥有世界上最丰富的黄金储备,有着超级公司以及销售者可以进行各种经济活动的广阔的国内市场,特别是在新兴的汽车工业中。美国的高生活水平和迅速有效的资本投资都以互惠的方式进一步刺激了对制造业的大量投资,因为消费者实际上能够接受所有的产品,这使现有生产力得到提高。例如,1929年,美国生产了450万辆汽车,而法国生产了21.1万辆,英国生产了18.2万辆,德国生产了11.7万辆。毫不奇怪,美国为了满足蒸蒸日上的制造业对橡胶、锡、石油和其他原料的需要而大幅度提高了进口额。但在整个20世纪20年代,出口商品,特别是汽车、农业机械、办公设备这一类走俏商品的出口也扩大了。美国向海外投资的迅速增长帮了整个出口贸易的大忙。尽管这一切都是众所周知的,但注意到如下事实仍会令人惊讶不已:在这一时期,美国的“生产量比其他六大国加在一起还要多”;“美国制造业的人均生产总值几乎比英国或德国的高一倍,是苏联或意大利的10~11倍。这就更进一步显示出美国占压倒优势的强大生产力”。

While it is also true, as the author of the above lines immediately notes, “that the United States’ political influence in the world was in no respect commensurate with her extraordinary industrial strength,”147 that may not have been so important in the 1920s. In the first place, the American people decidedly rejected a leading role in world politics, with all the diplomatic and military entanglements which such a posture would inevitably produce; provided American commercial interests were not deleteriously affected by the actions of other states, there was little cause to get involved in foreign events—especially those arising in eastern Europe or the Horn of Africa. Secondly, for all the absolute increases in American exports and imports, their place in its national economy was not large, simply because the country was so self-sufficient; in fact, “the proportion of manufactured goods exported in relation to their total production decreased from a little less than 10 percent in 1914 to a little under 8 percent in 1929,” and the book value of foreign direct investments as a share of GNP remained unaltered148—which helps to explain why, despite a widespread acceptance of world-market ideas in principle, American economic policy was much more responsive to domestic needs. Except in respect to certain raw materials, the world outside was not that important to American prosperity. Finally, international affairs in the decade after 1919 did not suggest the existence of a major threat to American interests: the Europeans were still quarreling but much less so than in the early 1920s, Russia was isolated, Japan quiescent. Naval rivalry had been contained by the Washington treaties. In such circumstances, the United States could reduce its army to a very small size (about 140,000 regulars), although it did allow the creation of a reasonably large and modern air force, and the navy was permitted to develop its aircraft-carrier and heavy-cruiser programs. 149 While the generals and admirals predictably complained about receiving insufficient resources from Congress, and certain damaging measures were done to national security (like Stimson’s 1929 decision to wind up the code-breaking service on the grounds that “gentlemen do not read each others mail”),150 the fact was that this was a decade in which the United States still could remain an economic giant but a military middleweight. It was perhaps symptomatic of this period of tranquillity that the United States still did not possess a superior civil-military body for considering strategic issues, like the Committee of Imperial Defence in Britain or its own later National Security Council. What need was there for one when the American people had decisively rejected the ideas of war?

但正如以上引语的作者立即指出的那样,美国在世界上的政治影响无论从哪一方面讲都与它强大的工业能力不相称,这可能在20世纪20年代并不十分重要。首先,美国人坚决拒绝在世界政治中扮演领袖角色,这种态度不可避免地也体现在一切外交和军事事务中。如果美国商业利益并未受到其他国家行为的有害影响,那么就不会有任何理由卷入到外交事务中去——特别是发生在东欧或非洲之角的事件中。其次,美国进出口的绝对增长额,在国民经济中的地位并不重要,原因很简单,美国自给自足的能力很强。事实上,“美国制造业产品的出口量,与制造业的总产量之间的比,从1914年的近10%下降到1929年的近8%”,国外直接投资的账面价值在国民生产总值中的份额保持不变。这有助于解释为什么美国人在原则上普遍接受了国际市场这一观念,却在其经济政策的制定中仍主要针对国内需求。除了某些原材料外,外部世界对美国的繁荣并不重要。最后,1919年后的10年里,国际事务中不存在对美国利益的直接威胁:欧洲仍争吵不休,但同20世纪20年代初期相比,争吵则少多了;苏联处于孤立地位;日本处于静止状态;海军竞赛由于《华盛顿条约》的签订而受到限制。在这种情况下,尽管美国允许建立一支规模适中的现代化空军,也允许海军发展自己的航空母舰和重型巡洋舰计划,但美国把其部队减少到很小的数目(正规军约14万人)。当陆海军将领们对国会拨给的军费不足,以及对某些危害国家安全的措施(如1929年的史汀生决定停止破译密码,理由是君子不看他人信)发出有预见性的抱怨时,美国在这10年中仍然是经济巨人,但军事力量却处于中等水平。美国仍然没有一个考虑战略问题的高级文武官员联合机构,如英国的帝国国防委员会以及美国自己后来的国家安全委员会,也许这正说明了那一段时间的平静。当美国人坚决地拒绝战争观念时,这样的机构有什么必要呢?

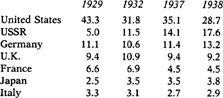

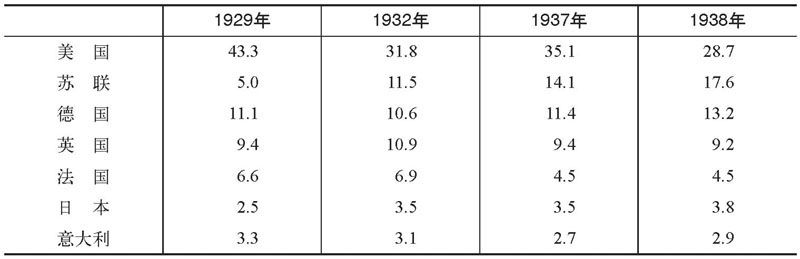

The leading role of the United States in bringing about the financial collapse of 1929 has been described above. 151 What is even more significant, for the purposes of measuring comparative national power, was that the subsequent depression and tariff wars hurt it much more than any other advanced economy. If this was partly due to the relatively uncontrolled and volatile nature of American capitalism, it was also affected by the fatal decision to opt for protectionism by the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930. Despite the complaints by U. S. farmers and some industrial lobbies about unfair foreign competition, the country’s industrial and agricultural productivity was such—as the surplus of exports over imports clearly showed—that a breakup of the open world trading order would hurt its exporters more than any others. “The nation’s GNP had plummeted from $98. 4 billion in 1929 to barely half that three years later. The value of manufactured goods in 1933 was less than onequarter what it had been in 1929. Nearly fifteen million workers had lost their jobs and were without any means of support During this same period the value of American exports had decreased from $5. 24 billion to $1. 61 billion, a fall of 69 percent. ”152 With other nations scuttling hastily into protective trading blocs, those American industries which did rely heavily upon exports were devastated. “Wheat exports, which had totaled $200 million ten years earlier, slumped to $5 million in 1932. Auto exports fell from $541 million in 1929 to $76 million in 1932. ”153 World trade collapsed generally, but the U. S. share of foreign commerce contracted even faster, from 13. 8 percent in 1929 to less than 10 percent in 1932. What was more, while certain other major powers steadily recovered output by the middle to late 1930s, the United States suffered a further severe economic convulsion in 1937 which lost much of the ground gained over the preceding five years. But because of what has been termed the “disarticulated world economy”154—that is, the drift toward trading blocs which were much more self-contained than in the 1920s—this second American slump did not hurt other countries so severely. The overall consequence was that in the year of the Munich crisis, the U. S. share of world manufacturing output was lower than at any time since around 1910 (see Table 30).

在1929年的金融崩溃中,美国首当其冲,这在前面已经作了描述。从国家力量的衡量和比较来看,更为重要的是,连续不断的萧条和关税战使美国遭受的损害比其他任何一个经济先进的国家都更为严重。这一方面是由于美国资本主义的相对失控和变化无常的本质,另一方面,美国也因采用了1930年通过的《斯姆特-霍利关税法》这一贸易保护主义的毁灭性政策而深受其害。尽管美国农场主和某些工业院外活动集团对不公平的国外竞争怨声载道,但美国的工业和农业生产力(贸易顺差的情况很明显)表明,打破公开的国际贸易秩序将使出口商受到更大的损害。“美国的国民生产总值1929年为984亿美元,3年后骤然下降,仅为1929年的一半,1933年,制造业产品的价值不到1929年的l/4。近1500万工人失业并且无任何生活来源……同期,美国出口品的价值从52.4亿美元下降到16.1亿美元,下降了69%。”由于其他国家迅即加入贸易保护集团,因此那些严重依赖于出口的行业遭到了严重打击。“10年前,小麦出口的价值为2亿美元,而1932年猛降到500万美元,汽车出口从1929年的5.41亿美元下跌为1932年的0.76亿美元。”世界贸易发生了全面崩溃,但美国的外贸额却缩减得更快,从1929年的13.8%,缩减到1932年的不足10%。而当其他主要大国从20世纪30年代中期至末期逐渐稳步地开始恢复时,美国却在1937年又一次遭到了更为严重的经济震动,这大大削弱了前5年所打下的经济根基。但由于“世界经济大脱节”(即向贸易集团靠拢)这一情况与20年代相比更加突出,因此,美国的第二次萧条对其他国家危害并不严重。总的结果是,在慕尼黑危机期间,美国在世界制造业总产量中所占份额要低于1910年以来的任何时期(见表30)。

Table 30. Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1929-1938155

表30 1929~1938年各国在世界制造业总产量中所占份额

(percent)

(百分比)

Because of the severity of this slump, and because of the declining share of foreign trade in the GNP, American policy under Hoover and especially under Roosevelt became even more introspective. In view of the strength of isolationist opinion and Roosevelt’s pressing set of problems at home, it could hardly be expected that he would give to international affairs the concentrated attention which both Cordell Hull and the State Department wished from him. Nevertheless, because of the crucial position which the United States continued to occupy in the world economy, there remains some substance in the criticism of “the occupation with domestic recovery” and the “desire for the appearance of immediate action and results [and] a national habit of policy formation that gave little sustained thought to the impact American programs might have on other nations. ”156 The 1934 ban upon loans to any foreign government which had defaulted on its war debts, the 1935 arms embargo in the event of war, and the slightly later prohibition of loans to any belligerent power simply made the British and French more cautious than ever about standing up to the fascist states. The 1935 denunciations of Italy were accompanied by enormous increases in American petroleum supplies to Mussolini’s regime, to the consternation of the British Admiralty. The various commercial restrictions upon Germany and Japan, in partial response to their aggression, “served to antagonize [both] without providing meaningful aid to the opponents of these nations. FDR’s economic diplomacy created enemies without winning friends or supporting prospective allies. ”157 Perhaps the most serious consequence— although the responsibility needs to be shared—was the mutual suspicions which arose between Whitehall and Washington precisely at a time when the dictator states were making their challenge. 158

由于萧条所产生的严重后果以及外贸额在国民生产总值中的下降,在胡佛特别是罗斯福领导下,美国的政策是对过去进行反思。从孤立主义的力量和罗斯福所面临的一系列迫切的内政问题来看,几乎很难指望他把注意力集中到国际事务上,而科德尔·赫尔和国务院却希望罗斯福这么做。然而,由于美国在世界经济中继续占据着关键性地位,人们对下列现象仍然提出一些实质性批评:“只忙于国内经济复苏,急于求成,希望行动与结果能即刻出现;美国制定政策的习惯是,对于美国计划可能对别国产生的影响不作连续性的考虑。”1934年,美国发出对不履行战争债务的所有外国政府停止贷款的禁令,1935年决定在战争状态下实行武器禁运,以及稍后发布的禁止向任何交战国提供贷款的法令,都使英法两国对抵抗法西斯国家的行为更加小心谨慎。1935年,随着对意大利的谴责,美国政府却向墨索里尼政权提供更多的石油,这使英国海军部感到惊恐万分。对德国和日本实行的贸易限制,一方面是对它们的侵略行径所做出的反应,另一方面“也起到了反作用,它没有向侵略国家的对手提供有意义的援助,富兰克林·罗斯福的经济外交政策树立了很多敌人,却没有赢得朋友或支持未来的盟国”。也许最严重的后果是,尽管这一责任需共同承担,但在独裁国家向白厅和华盛顿进行挑战这一关键时刻,白厅和华盛顿之间却在互相猜疑。

By 1937 and 1938, however, Roosevelt himself seems to have become more worried by the fascist threats, even if American public opinion and economic difficulties restrained him from taking the lead. His messages to Berlin and Tokyo became firmer, his encouragement of Britain and France somewhat warmer (even if that hardly helped those two democracies in the short term). By 1938, secret Anglo- American naval talks were taking place about how to deal with the twin challenges of Japan and Germany. The president’s “quarantine” speech was an early sign that he would move toward economic discrimination against the dictator states. Above all, Roosevelt now pressed for large-scale increases in defense expenditures. As the figures in Table 26 above show, even in 1938 the United States was spending less on armaments than Britain or Japan, and only a fraction of the sums spent by Germany and the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, aircraft production virtually doubled between 1937 and 1938, and in the latter year Congress passed a “Navy Second to None” Act, allowing for a massive expansion in the fleet. By that time, too, tests were taking place on the prototype B-17 bomber, the Marines Corps was refining its doctrine of amphibious warfare, and the army (while not yet possessing a decent tank) was grappling with the problems of armored warfare and planning to mobilize a vast force. 159 When war broke out in Europe, none of the services was at all ready; but they were in better shape, relative to the demands of modern warfare, than they had been in 1914.

不过,到1937和1938年,罗斯福对法西斯的威胁似乎更为担忧了。尽管美国舆论和经济困境制止了他发挥主导作用,但他给柏林和东京发出的信息已变得较为强硬了,他对英国和法国的鼓励已变得有几分热情了(尽管在短期内对这两个民主国家几乎没什么帮助)。1938年,英美两国海军就对付日本和德国的双重挑战问题举行了秘密会谈。美国总统的“隔离演说”是一个最初的信号,表明他将对独裁国家采取经济制裁。此外,罗斯福迫切要求大规模增加国防开支。如表26所显示的数字,1938年,美国用于军备的费用不及英国或日本,仅是德国和苏联的很少一部分,不过飞机生产在1937年到1938年实际上翻了一番。1938年,美国国会通过了海军优先法案,允许舰队大规模扩充。此时,B-17轰炸机样机正在试制中,美国海军陆战队正在完善两栖作战的理论,陆军(尽管还没有像样的坦克)正在解决装甲部队作战所带来的困难,并计划组建一支庞大的部队。当战争在欧洲爆发时,美国各军种都未做好准备,但它们就现代战争的要求来说,则比1914年时所处的状态相对要好些。

Even these rearmament measures scarcely disturbed an economy the size of the United States. The key fact about the American economy in the late 1930s was that it was greatly underutilized. Unemployment was around ten million in 1939, yet industrial productivity per man-hour had been vastly improved by investments in conveyor belts, electric motors (in place of steam engines), and better managerial techniques, although little of this showed through in absolute output figures because of the considerable reduction in work hours by the labor force. Given the depressed demand, which the 1937–1938 recession did not help, the various New Deal schemes were insufficient to stimulate the economy and take advantage of this underutilized productive capacity. In 1938, for example, the United States produced 26. 4 million tons of steel, well ahead of Germany’s 20. 7 million, the USSR’s 16. 5 million, and Japan’s 6. 0 million; yet the steel industries of those latter three countries were working to full capacity, whereas two-thirds of American steel plants were idle. As it turned out, this underutilization was soon going to be changed by the enormous rearmament programs. 160 The 1940 authorization of a doubling (!) of the navy’s combat fleet, the Army Air Corps’ plan to create eighty-four groups with 7,800 combat aircraft, the establishment (through the Selective Service and Training Act) of an army of close to 1 million men—all had an effect upon an economy which was not, like those of Italy, France, and Britain, suffering from severe structural problems, but was merely underutilized because of the Depression. Precisely because the United States had an enormous spare capacity whereas other economies were overheating, perhaps the most significant statistics for understanding the outcome of the future struggle were not the 1938 figures of actual steel or industrial output, but those which attempt to measure national income (Table 31) and, however imprecise, “relative war potential” (Table 32). For in each case they remind us that if the United States had suffered disproportionately during the Great Depression, it nonetheless remained (in Admiral Yamamoto’s words) a sleeping giant.

这些扩军备战措施对美国的经济实力几乎没有影响。20世纪30年代末,美国经济的关键问题在于其经济潜力未得到充分利用。1939年时,虽然失业人数大约为1000万,但由于对传送带、电动机(代替了蒸汽机)进行了广泛投资,对管理技术进行了改善,因而使个人每小时的劳动生产率得到了极大的提高(尽管由于工人的工作时间大大减少,而使生产率的提高在绝对生产量的数字中没有显示出来)。由于需求下降,而1937~1938年的衰退也未能促使需求回升,因此各种新政计划想要刺激经济和利用未充分挖掘的生产力,但这方面做得也是不够的。比如,1938年,美国生产了2640万吨钢,大大领先于德国的2070万吨、苏联的1650万吨和日本的600万吨,但后3个国家的钢铁工业是在满负荷的情况下进行生产的,而美国则有2/3的钢厂闲置未用。只是后来大规模的扩军计划才迅速改变了这种设备利用不足的局面。1940年美国海军战舰增加l倍,陆军航空兵计划建立84个大队并拥有7800架可供作战的飞机,通过选征兵役制和训练法,建立一支有近百万人的陆军。这些计划都得到当局批准,所有这一切都对经济产生了影响。美国经济由于大萧条而未得到充分利用,不像意大利、法国和英国经济那样,由于体制问题而遭到严重损害。严格地说,因为其他国家的经济都已紧张过度,而美国经济却仍有着巨大的剩余能力,所以,也许用来理解未来战争结局的最重要的数据不是1938年的钢或工业总产量的统计数字,而是那些能衡量国民收入(见表31)以及不太精确的“相对战争潜力”的数字(见表32),因为在这两种情况下,这些数字提醒我们,虽说美国在大萧条时期受到了比例失调的打击,但是,用日本海军大将山本五十六的话说,它仍然是个沉睡的巨人。

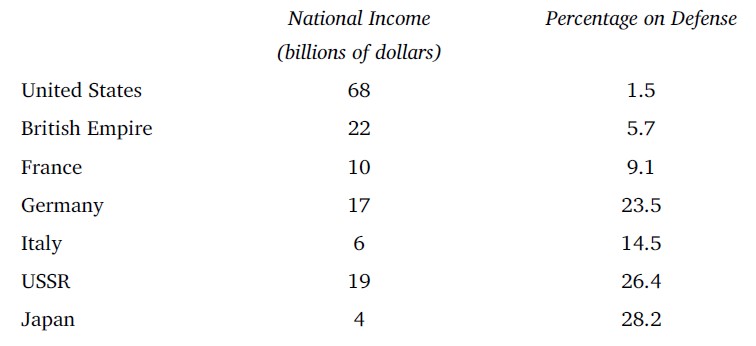

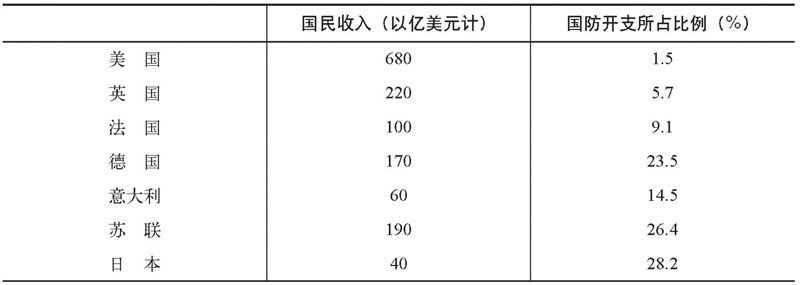

Table 31. National Income of the Powers in 1937 and Percentage Spent on Defense161

表31 1937年各大国国民收入与国防开支的比例

Table 32. Relative War Potential of the Powers in 1937 162

表32 1937年各大国的相对战争潜力

The awakening of this giant after 1938, and especially after 1940, provides a final confirmation the crucial issue of timing in the arms races and strategical calculations of this era. Like Britain and the USSR a little earlier, the United States was now endeavoring to close the armaments gap which had been opened up by the prior and heavy defense spending of the fascist states. That it could outspend any other country, if the political will existed at home, was clear from the statistics: even as late as 1939, U. S. defense composed only 11. 7 percent of total expenditures and a mere 1. 6 percent of GNP163—percentages far, far less than in any of the other Great Powers. An increase in the defense-spending share of the American GNP to bring it close to the proportions devoted to armaments by the fascist states would automatically make the United States the most powerful military state in the world. There are, moreover, many indications that Berlin and Tokyo realized how such a development would constrict their opportunities for future expansion. In Hitler’s case, the issue is complicated by his scorn for the United States as a degenerate, miscegenated power, but he also sensed that he dared not wait until the mid-1940s to resume his conquests, since the military balance would by then have decisively swung to the Anglo-French-American camp. 164 On the Japanese side, because the United States was taken more seriously, the calculations were more precise: thus, the Japanese navy estimated that whereas its warship strength would be a respectable 70 percent of the American navy in late 1941, “this would fall to 65 percent in 1942, to 50 percent in 1943, and to a disastrous 30 percent in 1944. ”165 Like Germany, Japan also had a powerful strategical incentive to move soon if it was going to escape from its fate as a middleweight nation in a world increasingly overshadowed by the superpowers.

1938年后,特别是1940年后,这个巨人苏醒了,并最后证实了当时军备竞赛的时间选择这一关键问题,以及那一时期的战略预测。像不久前的英国和苏联一样,美国现在试图弥合与法西斯国家在军备上的差距,它是由这些法西斯国家优先的、巨大的国防开支所造成的。如果国内有这种政治意愿,美国的国防开支可以超过任何国家,下面的统计数字清楚地表明了这一点:甚至直到1939年,美国防务开支仅为预算总支出的11.7%,占国民生产总值的1.6%,这个百分比远远低于其他任何大国。美国国民生产总值中国防开支比例增加后,同法西斯国家用于军备的开支比例基本接近,这自然而然就使美国成为世界上最强大的军事国家。另外,有许多迹象表明,柏林和东京认识到,美国的这种发展速度将使它们进一步扩张的机会受到限制。就希特勒来说,他鄙视美国是一个堕落和种族混杂的国家,认为这会使问题复杂化,但他也意识到,不能等到20世纪40年代中期再进行征服,因为到那时,军事优势肯定会转向英法美阵营。就日本来说,它对待美国的态度更为认真,因此考虑问题也就更为精细。日本海军的战舰力量在1941年末为美国的70%,“1942年将下降为65%,1943年下降为50%,而到1944年就会下降到灾难性的30%。”日本作为一个中等力量的国家,它想摆脱超级大国与日俱增的威胁,因此跟德国一样,它也有一种在战略上立即采取行动的强大动力。