The New Strategic Landscape

新的战略态势

The outlines of that new order were already being described by American military planners even as the conflict was at its height. As one of their policy papers expressed it:

早在战争还在激烈进行时,美国的军事计划人员就已经勾画出了新秩序的轮廓。一份政策性的文件这样写道:

The successful termination of the war against our present enemies will find a world profoundly changed in respect of relative national military strengths, a change more comparable indeed with that occasioned by the fall of Rome than with any other change occurring during the succeeding fifteen hundred years. … After the defeat of Japan, the United States and the Soviet Union will be the only military powers of the first magnitude. This is due in each case to a combination of geographical position and extent, and vast munitioning potential. 33

与我们目前敌人的战争胜利结束后,我们会发现,各个国家的军事力量的消长将发生意义极为深远的变化。其意义之深远,在罗马陷落后的1500年中,没有什么可与之相比。击败日本后,只有美国和苏联堪称第一军事强国;其原因均归结于它们的地理位置、辽阔的幅员和巨大的军火生产潜力。

While historians might quibble at the claim that nothing of a comparable nature had occurred during the past fifteen hundred years, it was becoming clear that the global balance of power after the war would be totally different from that preceding it. Former Great Powers—France, Italy—were already eclipsed. The German bid for mastery in Europe was collapsing, as was Japan’s bid in the Far East and Pacific. Britain, despite Churchill, was fading. The bipolar world, forecast so often in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, had at last arrived; the international order, in DePorte’s words, now moved “from one system to another. ”34 Only the United States and the USSR counted, so it seemed; and of the two, the American “superpower” was vastly superior.

历史学家们可能会吹毛求疵地对“在过去1500年中没有任何事件具有可与之相比较的性质”一说提出异议,但情况已日趋明朗:战后的世界力量对比将完全不同于战前。法国和意大利这两个昔日的大国,已黯然失色;德国、日本称霸欧洲和远东太平洋的企图正在烟消云散;英国尽管有丘吉尔,但也正在衰落。19世纪末、20世纪初,许多人经常预测的两极世界终于到来了。至于国际秩序,用德·波特的话说,现在已从“一个体系过渡到另一个体系”。只有美国和苏联与其外表一致,可谓世界的两极;而在这两个“超级大国”中,美国则享有巨大的优势。

Simply because much of the rest of the world was either exhausted by the war or still in a stage of colonial “underdevelopment,” American power in 1945 was, for want of another term, artificially high, like, say, Britain’s in 1815. Nonetheless, the actual dimensions of its might were unprecedented in absolute terms. Stimulated by the vast surge in war expenditures, the country’s GNP measured in constant 1939 dollars rose from $88. 6 billion (1939) to $135 billion (1945), and much higher ($220 billion) in current dollars. At last, the “slack” in the economy which the New Deal had failed to eradicate was fully taken up, and underutilized resources and manpower properly exploited: “During the war the size of the productive plant within the country grew by nearly 50 percent and the physical output of goods by more than 50 percent. ”35 Indeed, in the years 1940 to 1944, industrial expansion in the United States rose at a faster pace—over 15 percent a year—than at any period before or since. Although the greater part of this growth was caused by war production (which soared from 2 percent of total output in 1939 to 40 percent in 1943), nonwar goods also increased, so that the civilian sector of the economy was not encroached upon as in the other combatant nations. Its standard of living was higher than any other country’s, but so was its per capita productivity. Among the Great Powers, the United States was the only country which became richer—in fact, much richer—rather than poorer because of the war. At its conclusion, Washington possessed gold reserves of $20 billion, almost two-thirds of the world’s total of $33 billion. 36 Again, “… more than half the total manufacturing production of the world took place within the U. S. A. , which, in fact, turned out a third of the world production of goods of all types. ”37 This also made it by far the greatest exporter of goods at the war’s end, and even a few years later it supplied one-third of the world’s exports. Because of the massive expansion of its shipbuilding facilities, it now owned half of the world supply of shipping. Economically, the world was its oyster.

世界绝大部分地区被第二次世界大战搞得精疲力竭,或仍为“不发达的民地”,而1945年美国实力之强,犹如1815年的英国,只能用“非同一般”来形容。此外,其实力从绝对意义上说,也是史无前例的。由于战争开支的巨大刺激,美国的国民生产总值若以1938年的美元不变价格计算,从1939年的886亿美元增至1945年的1350亿美元;若以目前的美元价格计算,则增至2200亿美元。“新政”也未能消灭的“经济萧条”,在战争中被彻底根除;未能充分使用的资源和人力都得到了适当的利用。“在战争期间,美国工厂的规模扩大了近50%;产品产量增长了50%以上。”1940~1944年,美国工业以更快的速度增长,每年增长率超过了15%。这是空前绝后的。虽然这一增长在很大程度上是由战时军用物资生产所引起的(军用物资在工业总产量中的比重从1939年的2%,剧增至1943年的40%),但非军用品的生产也增加了。因此,美国并未像其他交战国那样压缩国民经济中的民用部门的生产。美国的生活水平、人均产值都高于其他国家。在世界大国中,美国是唯一因战争而大发其财,而不是因战争变得穷困潦倒的国家。在战争结束时,华盛顿的黄金储备为200亿美元,几乎占世界总量330亿美元的2/3。此外,“世界一半以上的制造业生产量是由美国承担的,美国生产的各种产品占世界总量的1/3”。这使得美国在战争结束时成为世界最大的出口国;就是在数年后,美国产品仍占世界出口总量的1/3。由于美国造船业的急剧膨胀,其船舶总吨位占世界的一半。从经济上说,美国可不受限制地在世界上为所欲为。

This economic power was reflected in the military strength of the United States, which at the end of the war controlled 12. 5 million service personnel, including 7. 5 million overseas. Although this total was naturally going to shrink in peacetime (by 1948, the army’s personnel was only one-ninth what it had been four years earlier), that merely reflected political choices, not real military potential. Given the early postwar assumptions about the limited overseas roles of the United States, a better indication of its strength lay in the tallies of its modern weaponry. By this stage, the U. S. Navy was unquestionably “second to none,” its fleet of 1,200 major warships (centered upon dozens of aircraft carriers rather than battleships) now being considerably larger than the Royal Navy’s, with no other significant maritime force existing. In both its carrier task forces and its Marine Corps divisions, the United States had amply demonstrated its capacity to project its power across the globe to any region accessible from the sea. Even more imposing was the American “command of the air”; the 2,000-plus heavy bombers which had pounded Hitler’s Europe and the 1,000 ultra-long-range B-29s which had reduced many Japanese cities to ashes were to be supplemented by even more powerful jet-propelled strategic bombers like the B-36. Above all, the United States possessed a monopoly of atomic bombs, which promised to unleash a devastation upon any future enemy as horrific as that which had occurred at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. 38 As later analyses have pointed out, American military power may actually have been less than it seemed (there were very few A-bombs in stock, and dropping them had large political implications), and it was difficult to use it to influence the conduct of a country as distant, inscrutable, and suspicious as the USSR; but the image of ineffable superiority remained undisturbed until the Korean War, and was reinforced by the pleas of so many nations for American loans, weapons, and promises of military support.

美国的经济实力也表现在其军事实力上。在战争结束时,美国有1250万名现役军人,其中750万人驻在海外。虽然其兵力总数在平时自然要减少(到1948年,美国陆军的人数只有4年前的1/9),但这仅是政治抉择的反映,并不反映美国真实的军事潜力。由于美国在战后初期设想自己在海外的作用将是有限的,它认为用其现代化武器来显示自己的力量是更好的选择。当时美国海军雄踞全球,“独一无二”。其舰队拥有l200艘大型军舰(以数十艘航空母舰而不是战列舰为核心组成作战舰队),实力远远超过英国皇家海军,没有任何国家的海军可与之匹敌。美国航空母舰特混编队和海军陆战队,已充分显示了美国通过海洋向世界各地投送兵力的能力。美国的“制空权”则更为壮观:它的2000多架重型轰炸机曾把希特勒的欧洲炸得稀烂;它的1000架超远程B-29型轰炸机曾使许多日本城市化为灰烬。现在它又有了像B-36型轰炸机那样更为强大的喷气式战略轰炸机。最重要的是,美国垄断着原子弹,可对任何未来的敌人实施像广岛和长崎那样可怕的毁灭性打击。然而,正像后来的分析所指出的那样,美国的军事力量其实没有像人们想象的那样强大(美国只储备有几枚原子弹,而且要顾及使用原子弹会引起很大的政治后果),美国也难以运用其军事力量来影响像苏联这样相距遥远、充满怀疑、像谜一样的国家的行为。但是,在朝鲜战争前,美国的这种飘飘然的自我优势感并没有被触动;由于那么多的国家请求美国提供贷款、武器和军事援助,它的这种感觉还有所加强。

Given the extraordinarily favorable economic and strategical position which the United States thus occupied, its post-1945 outward thrust could come as no surprise to those familiar with the history of international politics. With the traditional Great Powers fading away, it steadily moved into the vacuum which their going created; having become number one, it could no longer contain itself within its own shores, or even its own hemisphere. To be sure, the war itself had been the primary cause of this projection outward of American power and influence; because of it, for example, in 1945 it had sixty-nine divisions in Europe, twenty-six in Asia and the Pacific, and none in the continental United States. 39 Simply because it was politically committed to the reordering of Japan and Germany (and Austria), it was “over there”; and because it had campaigned via island groups in the Pacific, and into North Africa, Italy, and western Europe, it had forces in those territories also. There were, however, many Americans (especially among the troops) who expected that they would all be home within a short period of time, returning U. S. armedforces deployments to their pre-1941 position. But while that idea alarmed the likes of Churchill and attracted isolationist Republicans, it proved impossible to turn the clock back. Like the British after 1815, the Americans in their turn found their informal influence in various lands hardening into something more formal—and more entangling; like the British, too, they found “new frontiers of insecurity” whenever they wanted to draw the line. The “Pax Americana” had come of age. 40

鉴于美国所处的非常有利的经济和战略地位,美国的势力在1945年后便向外迅猛发展。这对于熟悉国家政治史的人来说,是不足为奇的。随着传统大国的衰败,美国稳步地填补了它们撤走后所留下的真空。在变成了头号强国后,美国就不会再把自己局限在自己的疆界内,或者自己所处的半球内。毋庸赘述,战争本身是美国势力和影响向外扩张的主要根源。例如,1945年,美国在欧洲驻有69个师,在亚洲太平洋地区驻有26个师,而在美国本土却一个师也没有。美国因负有重建日本、德国(以及奥地利)的政治义务,所以它就“待在那里”;美国军队在太平洋上是越岛作战,并进入北非、意大利和西欧战斗过,因此便在这些地区留驻军队。但是,许多美国人(特别是军人),希望在战争结束后能很快回国,将美国武装力量的部署恢复到1941年以前的状况。这种想法虽使丘吉尔大吃一惊,并引起了奉行孤立主义的共和党人的注意,但要使时钟倒转是不可能的。犹如1815年后的英国人那样,这次轮到美国人发现他们在各地的非正式影响已发展成为无法摆脱的更加正式的影响了。像英国人一样,每当美国人想画一条安全界线时,他们就会发现“不安全的新边疆”。“美国统治下的和平时代”已经到来了。

The economic aspects of this new order were, at least, predictable enough. During the war, internationalists like Cordell Hull had argued, with some reason, that the global crisis of the 1930s had been in large part caused by a malfunctioning of the international economy: by protective tariffs, unfair economic competition, restricted access to raw materials, autarkic governmental policies. This eighteenth-century Enlightenment belief that “unhampered trade dovetails with peace”41 was joined by the pressures exerted by export-oriented industries, which feared that a postwar slump might follow the decline in U. S. government spending unless new overseas markets were opened up to absorb the products of America’s enhanced productivity. To this was added a determined, and perhaps excessive, advocacy by the military to ensure American control of (or unrestricted access to) strategically critical materials such as oil, rubber, and metal ores. 42 All this combined to make the United States committed to the creation of a new world order beneficial to the needs of western capitalism and, of course, to the most flourishing of the western capitalist states— though with the longer-term, Adam Smithian assurance that “the more efficient distribution of resources brought about by unimpeded trade would raise productivity all around and thus increase everybody’s purchasing power. ”43 Hence the package of international arrangements hammered out between 1942 and 1946— the setting-up of the International Monetary Fund, of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development—and then the later General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Those countries wishing to secure some of the monies available for reconstruction and development under this new economic regime found themselves obliged to conform to American requirements on free convertibility of currencies and open competition (as the British did, despite their efforts to preserve imperial preference)44—or to stand clear of the entire system (as the Russians did, when they perceived how incompatible this was with socialist controls).

这种新秩序的经济情况至少是人们可以预料到的。在大战中,国际法学家们(如科德尔·赫尔)就曾正确地指出,20世纪30年代的全球性危机在很大程度上是由国际经济机能失调引起的。具体地说,是保护主义关税、不公平经济竞争、获得原材料的途径有限、政府闭关自守的政策引起的。这种18世纪启蒙运动的“不受阻碍的贸易意味着和平”的信念,受到了出口型工业的有力冲击。出口工业界担心,如果不开辟新的海外市场来吸收产量激增的美国产品,随着战后美国政府开支的减少,出口工业就会衰退。此外,美国军方坚决(甚至过分地)主张,美国应控制(或可以不受限制地获得)关键性的战略原材料,如石油、橡胶、金属矿藏等。所有这些因素加起来,便使美国致力于建立某种有利于满足西方资本主义需要(尤其有利于西方资本主义国家最大限度繁荣起来)的国际新秩序。这一新秩序从长远看,符合亚当·斯密的保证:“不受阻碍的贸易越能提高资源分配的效率,全面提高生产率,进而增强所有人的购买力就越有可能。”这样,在1942~1946年,世界上便出现了一系列国际经济组织——国际货币基金组织、国际复兴开发银行,后来还缔结了“关税与贸易总协定”。在这一新的经济制度下,希望能保证获得复兴与开发资金的国家,发现自己不得不屈从美国的要求,同意自由兑换货币和开展自由竞争(就像英国人那样,尽管他们还努力保持帝国特惠制);否则就须像苏联人所做的那样,发现这一制度与其社会主义控制制度水火不容时,完全避开这一制度。

The practical flaws in such arrangements were, first, that the amount of money available was simply insufficient to deal with the devastation caused by six years of total war; and, secondly, that a laissez-faire system inevitably works to the advantage of the country in the most competitive position—in this case, the undamaged, hyper-productive United States—and to the detriment of those less well equipped to compete—nations devastated by war, with boundaries altered, masses of refugees, bombed-out housing, worn-out machinery, ruinous debts, lost markets. Only the later American perception of the twin dangers of widespread social discontent in Europe and growing Soviet influence, which stimulated the creation of the Marshall Plan, permitted funds to be released for the substantial industrial redevelopment of the “free world. ” By that time, however, the expansion of American economic influence was going hand in hand with the erection of an array of military-base and security treaties across the globe (below, pp. 389–90). Here, too, there are many parallels with the expansion of British bases and treaty relationships after 1815; but the most noticeable difference was that Britain, on the whole, was able to avoid the plethora of fixed and entangling alliances with other sovereign countries which the United States was now assuming. Almost all of these American commitments were, it is true, “a response to events”45 as the Cold War unfolded; but regardless of the justification, the blunt fact was that they involved the United States in a degree of global overstretch totally at variance with its own earlier history.

这些安排在实践中是有缺陷的。第一个缺陷是所提供的资金根本不足以医治6年总体战造成的巨大创伤。第二个缺陷是,放任自流的体制必定只对竞争能力最强的国家有利,也就是说,只对未受战争破坏、生产力膨胀的美国有利;而对那些因受战争破坏、设备差、竞争力弱的国家,如边界已变动、难民成群、房屋被炸、机器破旧、债务深重、失去市场的国家,则非常有害。直到美国察觉欧洲普遍不满与苏联的影响日益扩大的危险同时出现时,它才被迫制订了“马歇尔计划”,答应为大规模恢复“自由世界”的工业提供巨额资金。但是,到这时已出现了美国的经济扩张与美国在世界各地建立军事基地、订立安全条约齐头并进的局面。这与英国在1815年后四处建立基地、订立条约的情况有许多相似之处。可是,最明显的不同之处是,总的来说,英国能避免与其他主权国家过多地建立固定的和含混的联盟关系,而美国现在则承担这种义务。确实,随着“冷战”的展开,美国的这些义务几乎都是“对事件做出的一种反应”。但是,无论承担这些义务是否有正当的理由,其结果都是使美国一反自己早期的历史,而过多地卷入了国际纠纷。

Little of this seems to have worried the decision-makers of 1945, many of whom appear to have felt not only that this was the working out of “manifest destiny,” but that they now had a golden opportunity to put right what the former Great Powers had managed to mess up. “American experience,” exulted Henry Luce of Life magazine, “is the key to the future. … America must be the elder brother of nations in the brotherhood of man. ”46 Not only China, in which extremely high hopes were placed, but all of the other countries of what was soon to be termed the Third World were encouraged to emulate American ideals of self-help, entrepreneurship, free trade, and democracy. “All these principles and policies are so beneficial and appealing to the sense of justice, of right and of the well-being of free peoples everywhere,” Hull prophesized, “that in the course of a few years the entire international machinery should be working fairly satisfactorily. ”47 Whoever was so purblind as not to appreciate that fact—whether old-fashioned British and Dutch imperialists, or leftward-tending European political parties, or the grim-faced Molotov—would be persuaded, by a mixture of sticks and carrots, in the right direction. As one American official put it, “It is now our turn to bat in Asia”;48 and, he might have added, nearly everywhere else as well.

1945年时的美国决策人看来对此并不感到有什么不安;相反,许多人还认为,这不仅是“显示天意”,而且还认为他们现在已有了宝贵良机,由美国来理顺被原先的大国搞得乱七八糟的关系。亨利·卢斯在《生活》杂志上狂喜地写道:“美国的经验是通向未来的关键……美国在全人类的国际大家庭中必须是老大哥。”美国还鼓励后来被称为“第三世界”的所有国家效法美国人的自助、企业家精神、自由贸易和民主等原则,对中国尤其寄予厚望。赫尔写道:“这些原则和政策对增强各地自由人民的正义感、权利意识和福利意识大有裨益,整个国际机制在几年之内就能运转得令人相当满意。”美国人人乐观,既然方向正确,根本不考虑用“胡萝卜加大棒”是否能说服英、荷老牌帝国主义者,欧洲左倾政党和冷面孔的莫洛托夫。一位美国官员甚至说:“现在轮到我们在亚洲击球了。”其实他还可以再加上一句:几乎在世界各地击球了。

The one area where American influence was highly unlikely to penetrate was that controlled by the Soviet Union, which in 1945 (and ever since) claimed to be the true victor of the fight against fascism. According to the Red Army’s statistics, it had smashed a total of 506 German divisions; and of the 13. 6 million German casualties and prisoners lost during the Second World War, 10 million met their fate on the eastern front. 49 Yet even before the Third Reich had collapsed, Stalin was switching dozens of divisions to the Far East, ready to unleash them upon Japan’s denuded Kwantung Army in Manchuria when the time was ripe; which turned out to be, perhaps unsurprisingly, three days after Hiroshima. The extended campaign on the western front more than reversed the disastrous post-1917 slump in Russia’s position in Europe; indeed, it actually restored it to something akin to that of the period 1814–1848, when its great army had been the gendarme of east-central Europe. Russian territorial boundaries expanded, in the north at the expense of Finland, in the center at the expense of Poland; and in the south, recovering Bessarabia, at the expense of Rumania. The Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were reincorporated into Russia. Part of East Prussia was taken, and a slice of eastern Czechoslovakia (Ruthenia, or Subcarpathian Ukraine) was also thoughtfully added, so that there was direct access to Hungary. To the west and southwest of this enhanced Russia lay a new cordon sanitaire of satellite states, Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria, and (until they wriggled free) Yugoslavia and Albania. Between them and the West, the proverbial “iron curtain” was falling; behind that curtain, Communist party cadres and secret police were determining that the entire region would operate under principles totally at variance with Cordell Hull’s hopes. The same was true in the Far East, where the swift occupation of Manchuria, North Korea, and Sakhalin not only avenged the war of 1904–1905, but allowed a link-up with Mao’s Chinese Communists, who were also unlikely to swallow the gospel of laissez-faire capitalism.

美国势力最难渗透进去的地区是苏联控制的地区。苏联自1945年以来,一直自称是打败法西斯的主要国家。根据苏联红军的统计,苏联共歼灭了德军506个师;德军在第二次世界大战中伤亡和被俘的1360万人中,有1000万人是在东线损失的。甚至在第三帝国崩溃之前,斯大林还向远东调去了几十个师,准备一旦时机成熟就向在中国东北的已大大削弱的日本关东军开战。因此,在美国向广岛投掷原子弹三天后苏联的对日宣战,就不令人惊奇了。西线的长期战事不仅完全改变了苏联在欧洲的地位,扭转了其1917年后地位暴跌的局面,而且还使苏联几乎恢复了它在1814~1848年间在欧洲的地位(当时它庞大的军队充当着东欧、中欧的宪兵角色)。苏联扩展了它的疆域:在北方割取了芬兰的部分领土;在中部掠取了波兰的一些领土;在南方则吞并了罗马尼亚的比萨拉比亚;爱沙尼亚、拉脱维亚和立陶宛三个波罗的海沿岸国家被重新并入苏联;它还深谋远虑地将东普鲁士的一部分、捷克斯洛伐克东部的一小片地区划归己有(路塞尼亚或次喀尔巴阡乌克兰),从而获得了直接进入匈牙利的通道。在其西面和西南面,势力壮大的苏联建立了由波兰、民主德国、捷克斯洛伐克、匈牙利、罗马尼亚、保加利亚及(挣脱约束前的)南斯拉夫和阿尔巴尼亚组成的新卫星国“防疫线”。在它们与西方之间就是众所周知的“铁幕”。在“铁幕”后面,苏联共产党的官员和秘密警察决心使这一整个地区以完全不同于科德尔·赫尔所希望奉行的原则行事。远东的情况也同样如此。苏联对中国东北、朝鲜北部和萨哈林岛(库页岛)的迅速占领,不仅报了1904~1905年日俄战争的一箭之仇,而且还与中国共产党人联结在一起,而后者也是不可能接受奉行自由放任主义的资本主义制度的。

But if this growth of Soviet influence looked imposing, its economic base had been badly hurt by the war—in contrast to the United States’ undisturbed boom. Russia’s population losses were appalling: 7. 5 million in the armed forces; 6–8 million civilians killed by the Germans; plus the “indirect” war losses caused by the reduced food rations, forced labor, and vastly increased hours of work, so that “altogether probably some 20–25 million Soviet citizens died premature deaths between 1941 and 1945. ”50 Since the casualties were mainly men, the consequent imbalance between the sexes greatly affected the country’s demographic structure and caused a severe drop in the birthrate. The material damage done in the Germanoccupied parts of European Russia, the Ukraine, and Belorussia was so large as to be beyond normal imaginings:

苏联势力影响的增长虽使人难以忘怀、不容忽视,但其经济基础受到了严重的破坏,与美国受惠于战争的繁荣经济相比,大为逊色。苏联人口损失骇人听闻:军队损失750万人,600万~800万平民被德国人杀害;再加上因粮食减少、强制劳动和大量增加工作时间而造成的“间接”战争损失,“在1941~1945年共有2000万~2500万苏联人过早地死去”。由于伤亡者主要是男子,两性的不平衡使国家的人口结构遭到了严重的破坏,人口出生率急剧下降。在德国占领的俄罗斯欧洲部分、乌克兰和白俄罗斯,物质损失之大,超出人们的想象:

Of the 11. 6 million horses in occupied territory, 7 million were killed or taken away, as were 20 out of 23 million pigs. 137,000 tractors, 49,000 grain combines and large numbers of cowsheds and other farm buildings were destroyed. Transport was hit by the destruction of 65,000 kilometers of railway track, loss of or damage to 15,800 locomotives, 428,000 goods wagons, 4,280 river boats, and half of all the railway bridges in the occupied territory. Almost 50 percent of all urban living space in this territory, 1. 2 million houses, were destroyed, as well as 3. 5 million houses in rural areas.

在被占领地区的1160万匹马中,被宰杀和掠走的达700万匹,2300万头猪中被抢走2000万头,13.7万台拖拉机、4.9万台谷物联合收割机和大量的牛棚、农场等其他建筑物被毁。运输网遭到的破坏是:6.5万公里长的铁路线被毁,损失了15800台机车、42.8万节车皮、4280艘内河船舶和被占领区内一半的铁路桥。这一地区近50%的城市居住面积、120万幢房屋被毁,农村地区房屋被毁达350万幢。

Many towns lay in ruins. Thousands of villages were smashed. People lived in holes in the ground. 51

许多城镇变为废墟。成千上万个村庄被夷平。人们都居住在地下的洞穴中。

It was scarcely surprising, therefore, that when the Russians moved into their “occupation zone” in Germany, they attempted to strip it of all movable assets, factory plant, rail lines, etc. , as well as demanding compensations from other eastern European territories (Rumanian oil, Finnish timber, Polish coal).

因此,苏联人一进入其德国占领区便大肆搜刮,把工厂设备、铁轨等一切可搬走的东西都弄走,并要求其他东欧国家赔偿(罗马尼亚用石油、芬兰用木材、波兰用煤)。对此,人们没有必要感到奇怪。

It was true that the Soviet Union had outproduced Greater Germany in the armaments battle as well as outfighting it at the front; but it had done so by an incredibly single-minded concentration upon military-industrial production and by drastic decreases in every other sector—consumer goods, retail trade, and agricultural supplies (though the decline in food output was chiefly caused by German plunderings). 52 In essence, therefore, the Russia of 1945 was a military giant and, at the same time, economically poor, deprived, and unbalanced. With Lend-Lease cut off, and having rejected later American monies because of the political conditions attached to them, the Soviet Union reverted to its post-1928 program of enforced economic growth from its own resources—with the same strong emphasis upon producer goods (heavy industry, coal, electricity, cement) and transport to the detriment of consumer goods and agriculture, and with a natural reduction in military expenditures from their wartime levels. The result, after initial difficulties, was “a minor economic miracle”53 so far as heavy industry was concerned, with output nearly doubling between 1945 and 1950. Obsessed by the need to rebuild the sinews of national power, the Stalinist regime had no problems in achieving that crude aim or in keeping the standard of living for most Russians down at pre-Revolution levels. Yet it also ought to be noted that, as with the post- 1922 growth, much of the “recovery” of industrial production consisted of getting back to the prewar output; in the Ukraine, for example, metallurgical and electrical output around 1950 had reached, or just exceeded, the 1940 figures. Once again, because of war, Russia’s economic growth had been choked back by a decade or so. More serious still, in the longer term, was the continued failure of the vital agricultural sector: with the emergency wartime incentive measures suppressed, and because of the totally inadequate (and misdirected) investment, farming wilted and food output slumped. Until his death, Stalin maintained his bitter vendetta against the peasantry’s preference for private plots, thereby ensuring that the traditional low productivity and high inefficiency of Russian agriculture would continue. 54

确实,苏联在军工生产和前线作战方面都战胜了德国。但是,苏联的胜利靠的是大幅度减少其他部门——消费品、零售贸易和农产品供应(虽然粮食产量的减少主要是由德国人掠夺造成的)的生产和活动,集中力量进行军工生产获得的。总之,1945年的苏联在军事上是一个巨人,但在经济上已沦为一个丧失了生活必需品、穷困潦倒的穷汉。随着租借物资供应的中断和苏联因美国附加的政治条件而拒绝接受美国的金钱,苏联又恢复使用它在1928年后利用本国资源提高经济增长速度的老办法:继续强调生产资料(重工业、煤炭、电力、水泥)的生产和发展运输业,从而给消费品工业和农业生产带来损害,并且自然地将军事开支从战时水平削减下来。结果,苏联在克服了最初遇到的困难后,在重工业方面创造了一个“小小的经济奇迹”,其重工业产量在1945~1950年增长了近1倍。为了重建国家实力源泉,达到这一冷酷的目标,斯大林政权不遗余力,甚至不惜把大多数苏联人的生活标准降低到革命前的水平上。值得注意的是,这时苏联工业的发展犹如其1922年以后的情况,工业生产的增长在很大程度上是“恢复”战前的产量。例如,乌克兰冶金业和电力工业的产量在1950年前后才达到或刚刚超过1940年的水平。由于战争的影响,俄国的经济发展再次停滞了大约10年的时间;更为严重的是,从长远看,至关重要的农业部门继续受到忽视。由于停止执行战时强制性应急措施和投资不足,(和瞎指挥)农业生产进一步萎缩,产量暴跌。斯大林到死也不同意农民拥有自留地。这样,苏联农业长期存在的生产水平低、效率低的问题便继续存在着。

By contrast, Stalin was clearly intent upon maintaining a high level of military security in the postwar world. Given the need to rebuild the economy, it was not surprising that the enormous Red Army was reduced by two-thirds after 1945, to the still very substantial total of 175 divisions, supported by 25,000 front-line tanks and 19,000 aircraft. It still would remain, therefore, the largest defense establishment in the world—a fact justified (in Soviet eyes, at least) by its need to deter future aggressors and, more prosaically, to keep control of its newly acquired satellites in Europe as well as its conquests in the Far East. Although this was an enormous force, many of its divisions existed only in skeleton form, or were essentially garrison troops. 55 Moreover, the service ran the danger which had befallen the gigantic Russian army in the decades after 1815—increasing obsolescence, in the face of new military advances. This was to be combated not only by a substantial reorganization and modernization of the army’s divisions,56 but also by committing the economic and scientific resources of the Soviet state to the development of new weapon systems. By 1947–1948, the formidable MiG-15 jet fighter was going into service, and—in imitation of the Americans and British—a long-range strategic air force had been created. Captured German scientists and technicians were being used to develop a variety of guided missiles. Even during the war, resources had been allocated for the development of a Soviet A-bomb. And the Russian navy, which had been a mere ancillary arm in the struggle against Germany, was also being transformed, with the addition of new heavy cruisers and even more oceangoing submarines. Much of this weaponry was derivative and, by western standards, unsophisticated. What could not be doubted, however, was the Soviet determination not to be left behind. 57

与此相对照的是,斯大林显然决心在战后保持一支高水平的军事力量。由于恢复经济的需要,规模庞大的苏联红军在1945年以后减少了2/3,但它仍很庞大,拥有175个师、2.5万辆一线坦克和1.9万架飞机,因而仍是世界上最庞大的一支军队。在苏联人眼里,要遏制未来的侵略者,更加自如地保持对东欧卫星国及对远东征服地区的控制,拥有这样一支军队是必要的。虽然苏联红军是一支庞大的军队,但它的许多师仅仅是“架子师”或主要担任守备的部队。此外,苏联红军还遇到了可能被军事技术进步甩在后面的危险。1815年的俄国庞大的军队在数十年后也曾遇到过这一危险。要克服这一危险不仅要对其军队的师团进行大规模的改编和现代化,而且还需投入国家的经济和科学力量来研制新武器系统。1947~1948年,令人望而生畏的米格-15型喷气战斗机开始服役;苏联还效法美国人和英国人,建立起一支远程战略空军。苏联还使用虏获的德国科学家和技术人员来研制各种导弹。甚至还在战争时期,苏联就抽调力量研制原子弹。在对德战争中仅充当助手的苏联海军也发生了变化,添置了新式重型巡洋舰和远洋潜艇。它的许多武器是仿制的,用西方的标准来衡量也不算先进。但不容置疑的是,苏联决心不甘落后。

The third major element in the buttressing of Russian power was Stalin’s renewed emphasis upon the internal discipline and absolute conformism of the late 1930s. Whether this was due to his increasing paranoia or a carefully calculated set of moves to reinforce his own dictatorial position—or a mixture of both—is hard to say; but the events spoke for themselves. 58 Anyone with foreign connections was suspect; returning prisoners-of-war were shot; the creation of the state of Israel, and thus an alternative source of Jewish loyalties, led to renewed anti-Semitic measures within Russia. The army leadership was cut down to size, with the respected Marshal Zhukov being removed as commander of the Soviet ground forces in 1946. Discipline within the Communist party itself, and admission to the same, was tightened; in 1948, the entire party leadership of Leningrad (which Stalin always disliked) was purged. Censorship was intensified, not only over literature and the creative arts, but also over the natural sciences, biology, linguistics. This overall “tightening” of the system naturally fitted in with the reasserted collectivization of agriculture mentioned earlier, and with the rise of Cold War tensions. It was also natural that a similar process of ideological stiffening and totalitarian controls should take place in the Soviet-dominated states of eastern Europe, where the elimination of rival parties, the holdings of show trials, the drive against individual rights and properties, became the order of the day. All this, and in particular the elimination of democracy in Poland and (in 1948) in Czechoslovakia, led to a considerable ebbing of western enthusiasm for the Soviet system. Again, it is unclear whether these measures were all carefully calculated—there was, and is, a crude logic in the Soviet elite’s desire to isolate its satellites as well as its own people from the ideas and riches of the West—or whether it simply reflected Stalin’s increasing paranoia as his end approached. Whatever the cause, there would be one massive stretch of territory totally immune from the influences of any “Pax Americana,” and indeed offering an alternative to it.

维系苏联实力的第三个重要原因,是斯大林重新强调内部纪律和20世纪30年代末期的那种绝对一致。斯大林这样做是出于他日趋严重的偏执狂症,还是出于他想通过一系列计划周密的行动来加强自己的专权地位,或两者兼而有之,我们还难以断定。但是,发生的事件本身说明了其原因。任何与外国有联系的人都被怀疑;遣返的战俘被枪毙了;以色列国家诞生后,犹太人可以选择自己的效忠对象,结果导致苏联国内重新采取反犹措施;军队将领的地位被削弱,德高望重的朱可夫元帅于1946年被解除苏联地面部队总司令的职务;苏联共产党的内部纪律和入党条件更加严格;1948年,列宁格勒全部苏联共产党的领导人(斯大林总是不喜欢他们)被清洗。苏联加强了检查制度,检查范围不仅涉及到文学和艺术领域,而且还扩大到自然科学、生物学和语言学领域。苏联制度内部的紧张化当然是与重新实行农业集体化和“冷战”紧张局势的出现相呼应的。自然,苏联统治下的东欧诸国也出现了类似的思想僵化和极权统治,在那里,消灭反对党、举行公开审判、否定个人权利和私人财产成了家常便饭。所有这些事件,尤其是波兰和(1948年)捷克斯洛伐克民主制度的颠覆,导致西方对苏联制度所持有的热情态度大为减弱。西方搞不清楚的是苏联的这些措施是周密策划的(完全合乎逻辑的是苏联领导集团热切希望,使其卫星国和卫星国的人民脱离西方的思想和富庶的影响),还是斯大林末日来临前偏执狂病加重的反映。无论其原因何在,世界上还是出现了一大片丝毫不受“美国统治下的和平”影响的地区,在人们前面形成了另一种发展局面。

This growth of the Soviet Empire appeared to confirm the geopolitical predictions of Mackinder and others that a gigantic military power would control the resources of the Eurasian “Heartland”; and that the further expansion of that state into the periphery or “Rimland” would need to be contested by the great maritime states if they were to preserve a global balance of power. 59 It would still be another few years before U. S. administrations, shaken by the Korean War, completely abandoned their earlier ideas of “One World” and replaced them with the image of an unrelenting superpower struggle across the international arena. Yet to a large extent this was implicit in the circumstances of 1945; the United States and the USSR were the only nations now capable, as de Tocqueville had once put it, of swaying the destinies of half the globe; and both had fallen prey to “globalist” thinking. “The USSR now is one of the mightiest countries of the world. One cannot decide now any serious problems of international relations without the USSR …” Molotov claimed in 1946,60 an echo of the earlier American intimation to Moscow (when it seemed that Churchill and Stalin might come to a private agreement over eastern Europe) that “in this global war there is literally no question, political or military, in which the United States is not interested. ”61 A serious clash of interests was inevitable.

苏联的壮大似乎证实了麦金德等地缘政治学家们的预言:欧亚大陆的“心脏地带”的资源将被一个庞大的军事强国控制;海洋强国若想保持全球力量均势,须抗击该国向大陆边缘地带的进一步扩张。几年后,朝鲜战争爆发了。美国政府大为震动,完全放弃了原先“一个世界”的想法,而代之以超级大国在国际舞台上展开殊死搏斗的格局。可是,在很大程度上,这种格局在1945年的局势中就隐约出现了,像德·托克维尔所预言的那样,美国和苏联正在成为能决定半个地球命运的两个国家,世界上只有这两个国家具有这种能力;但与此同时,两国也自然沦为“全球性思维”的牺牲品。1946年莫洛托夫宣称:“苏联现在是世界上最强大的国家之一,没有苏联参加,任何国家都不可能解决任何重大的国际关系问题……”这其实是美国对丘吉尔和斯大林莫斯科会晤(两人可能就东欧问题私下达成协议)所发表的声明的翻版。美国的声明这样说:“在这场全球性战争中,没有美国不关心的问题——无论是政治方面的,还是军事方面的。”利益的严重冲突终于不可避免了。

But what of those former Great Powers, now merely middleweight countries, whose collapse was the obverse side of the rise of the superpowers? It needs to be said immediately that the defeated fascist states of Germany, Japan, and Italy were in a different category from that of Great Britain and, perhaps, of France also in the immediate post-1945 period. When the fighting ceased, the Allies went ahead with their plans to ensure that neither Germany nor Japan would ever again be a threat to the international order. This involved not only the long-term military occupation of both countries but, in the German case, its division into four occupation zones and then, later, into two separate German states. Japan was stripped of its overseas acquisitions (as was Italy in 1943), Germany of its European gains and of its older territories in the east (Silesia, East Prussia, etc. ). The devastation caused by the strategic bombing, the overstraining of the transport system, the decline of the housing stock, and the lack of many raw materials and export markets was compounded by the Allied controls upon industry—and, in Germany, by the dismantling of industrial plant. German national income and output in 1946 was less than one-third that of 1938, a horrendous reduction. 62 In Japan, a similar economic regression had occurred; real national income in 1946 was only 57 percent that of 1934–1936 and real manufacturing wages were down to only 30 percent of the same; foreign trade was so minimal that even two years later, exports were only 8 percent and imports 18 percent of the 1934–1936 figure. Japan’s shipping had been eliminated by the war, the number of cotton spindles cut from 12. 2 million to 2 million, coal output halved, and so on. 63 Economically as well as militarily, their days as powerful nations seemed over.

昔日的大国现已成为中等国家,它们的崩溃是超级大国崛起的另一种衬托。那么这些国家的情况如何呢?需要立即说明的是,德、意、日法西斯战败国的情况,不同于1945年后的英国和法国。战火刚刚平息,盟国就着手实施自己的计划,以确保德、日不再成为对国际秩序的威胁。这些计划不仅包括对两国实行长期的军事占领,而且还把德国分为4个占领区(后来合并成两个德国)。日本像1943年的意大利那样,被剥夺了海外领地;德国丧失了它在欧洲所取得的一切利益和东部古老的领土(西里西亚和东普鲁士等)。战略轰炸、运输系统使用过度、住房条件的下降、许多原料不足和出口市场的缩小,已经给两国造成了巨大的灾难,而盟国对其工业的控制、(在德国的)拆迁工厂,又如雪上加霜。1946年德国的国民收入和国民生产总值竟不到1938年的1/3,真是可怕的倒退。日本经济也出现了类似的倒退情况。它在1946年的实际国民收入只相当于1934~1936年的57%;制造业的实际工资也只相当于这一时期的30%;对外贸易量微乎其微,甚至两年后的出口量才只有1934~1936年的8%,进口量则为18%。日本的海上航运在战争中被破坏殆尽;纱锭数量从1220万支减少到200万支;煤的产量减少了一半,如此等等。德、日作为强国的日子,无论从经济角度看,还是从军事角度看,似乎都结束了。

Although Italy had switched sides in 1943, its economic fate was almost as grim. For two years, Allied forces had fought and bombed their way up the peninsula, severely adding to the damage caused by Mussolini’s strategical extravagances. “In 1945 … Italy’s gross national product had reverted to the 1911 level and had diminished by about 40 percent in real terms, as compared with 1938. The population, despite war losses, had increased largely as a result of repatriation from the colonies and the halt in emigration. The standard of living was alarmingly low, and but for international aid, especially from the United States, many Italians would have died of starvation. ”64 Italian real wages were down to 26. 7 percent of their 1913 value by 1945. 65 In fact, all of these countries were terribly dependent upon American aid during this period; and, as such, were little more than economic satellites.

意大利虽然在1943年就改变了立场加入了盟国,但其经济情况也一样暗淡。盟军在意大利作战、轰炸持续时间达两年之久,横扫了意大利半岛,极大地加剧了墨索里尼战略冒险所造成的破坏。“在1945年……意大利的国民生产总值倒退到1911年的水平;与1938年相比,实际下降了40%。尽管战争给人口造成了损失,但由于意大利在殖民地的移民被遣返回国,向外移民停止,意大利的人口激增,致使生活水平降低到惊人的地步。如果没有国际援助,尤其是美国的援助,许多意大利人就被饿死了。”到1945年,意大利的实际工资下降到1913年的26.7%。这些国家在这个时期对美国的依赖程度骇人听闻,犹如美国的经济卫星国。

It was difficult to tell the difference, in economic terms, between France and Germany. Four years of plundering by the Germans had been followed by months of large-scale fighting in 1944; “most waterways and harbors were blocked, most bridges destroyed, much of the railway system temporarily unusable. ”66 Fohlen’s indices of French imports and exports shows them plunging to virtually nothing by 1944–1945; France’s national income by that time was only half that of 1938, itself a gloomy year. 67 France had no stocks of foreign currency, and the franc itself had not been accepted on the foreign exchanges; its value, when fixed at 50 to the dollar in 1944, was “purely fictitious,”68 and within a year it had slid to 119 to the dollar; by 1949, when things seemed more stable, it was 420 to the dollar. French party politics, and in particular the role of the Communist party, obviously interacted with these purely economic problems of reconstruction, nationalization, and inflation.

在经济方面,法国与德国的情况相差无几。法国被德国洗劫了4年后,其国土又遭受了1944年几个月大规模战斗的蹂躏,结果“绝大部分水道和港口被堵塞,绝大部分桥梁被摧毁,铁路系统的很大一部分暂时不能使用”。福仑的法国进出口贸易指数表明,到1944~1945年,法国的进出口实际上等于零,法国的国民收入那时只相当于1938年(法国最灰暗的年月)时的一半。法国的外汇储备已经枯竭;法郎在外汇兑换中已不被使用。法郎与美元的汇率在1944年被定为50∶1,但这个汇率完全是凭空制定的,1年内就降到119∶1。到1949年,当情况比较稳定时,法郎与美元的汇率仍高达420∶1。这些诸如重建、国有化和通货膨胀一类的纯经济问题,明显地影响了法国各政党,特别是共产党的作用。

On the other hand, the Free French had been members of the “Grand Alliance” against fascism and had fought in many of the major campaigns, as well as triumphing in their “civil” war against pro-Vichy forces in West Africa, the Levant, and Algeria. Given the German occupation of France and the division in French loyalties during the war, de Gaulle’s organization was heavily dependent upon Anglo-American aid—which de Gaulle resented, even as he demanded more. Nonetheless, the British were eager to see France reestablished as a strong military Power in Europe as a check to Russia, rather than a collapsing Germany, and so France acquired many of the accouterments of Great Power status: an occupation zone in Germany, permanent membership in the UN Security Council, and so on. Although it could not regain its former mandates in Syria and Lebanon, it did seek to reassert itself in Indochina and in the protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco; and with its overseas departments and territories, it still possessed the second-largest colonial empire in the world and was determined to hang on to it. 69 To many outside observers, especially the Americans, this attempt to regain the trappings of first-class power status while so desperately weak economically—and so dependent upon American financial support—was nothing more than a folie des grandeurs. And so, to a large extent, it was. Perhaps its chief consequence was to disguise, at least for some more years, the extent to which the strategical landscape of the globe had been altered by the war.

另一方面,“自由法国”曾是反法西斯“伟大联盟”的一员,参加过许多重大战役,在西非、地中海东部和阿尔及利亚反对亲维希的“内战”中取得了胜利。在战争中,德国占领了法国,法国人民的忠诚发生了分裂,在这种情况下,戴高乐不得不严重依赖英国和美国的援助。但是,戴高乐即使在要求给予更多的援助时,对后者也不满。由于英国迫切希望法国重新成为欧洲的军事大国,以接替正在垮台的德国去同苏联相抗衡,所以法国获得了许多大国的待遇和地位,如在德国有占领区,在联合国安理会担任常任理事国等。法国虽未能恢复它在叙利亚和黎巴嫩的委任统治,但它重新确定了自己在印度支那、突尼斯和摩洛哥的保护国地位。随着政府海外部的建立和海外领地的获得,法国仍是世界上第二大殖民帝国,并决心保持其殖民帝国的地位。在许多外国观察家(特别是美国人)看来,法国在经济上如此虚弱不堪并严重依靠美国财政援助过活时,还想跻身于世界上第一流大国之列,纯属“伟大的疯狂”。事实也确实如此。第二次世界大战极大地改变了全球的战略环境,但法国却仍想趾高气扬,结果它至少还需多年才能从旧梦中清醒过来。

Although most Britons in 1945 would have felt indignant at the comparison, the continued appearance of their nation and empire as one of the Great Powers of the world also disguised the new strategical balances—as well as making it psychologically difficult for decisionmakers in London to readjust to the politics of decline. The British Empire was the only major state which had fought through the Second World War from beginning to end. Under Churchill’s leadership, it had been unquestionably one of the “Big Three. ” Its military performance, at sea, in the air, even on land, had been significantly better than in the First World War. By August 1945, all the possessions of the king-emperor—including Hong Kong—were back in British hands. British troops and airbases were sprawled across North Africa, Italy, Germany, Southeast Asia. Despite heavy losses, the Royal Navy possessed over 1,000 warships, nearly 3,000 minor war vessels, and nearly 5,500 landing craft. RAF Bomber Command was the second-largest strategic air force (by far) in the world. And yet, as Correlli Barnett has forcefully pointed out, “victory” was not synonymous with the preservation of British power. The defeat of Germany [and its allies] was only one factor, if a highly important factor, in such a preservation. For Germany might be defeated and yet British power still be brought to an end. What counted was not so much “victory” in itself, but the circumstances of the victory, and in particular the circumstances in which England found herself. … 70

虽然在1945年大部分英国人理应对这种实力对比感到不平,但他们的国家和英帝国在表面上继续充当着世界的一个大国。这种做法掩盖了新的战略力量对比,也使伦敦的决策人难以在心理上做出调整,以适应政治上的这种衰落局面。英国是唯一自始至终参加第二次世界大战的大国。在丘吉尔的领导下,它毫无疑问是“三巨头”的一员。英军在海上、天空甚至陆地上的战绩,显著优于第一次世界大战。到1945年8月,英王的全部属地(包括中国香港)都回到英国手中,英国部队和空军基地遍布北非、意大利、德国和东南亚;皇家海军虽损失惨重,但仍拥有1000余艘战舰、近3000艘小型舰艇和5500艘登陆艇;皇家空军轰炸机司令部统帅着世界上的第二大战略空军部队。但是,正如科雷里·巴尼特有力地指出的:“胜利”并不是英国保持其力量的同义词。在英国保持其力量方面,击败德国(及其盟国)是一个因素,当然可以说是一个非常重要的因素。这是因为德国虽被击败,但英国也耗尽了自己的力量。因此,不应过多地考虑“胜利”本身,而应想想胜利的环境,特别是英国发现自己所处的环境。

For the blunt fact was that in securing a victorious outcome to the war the British had severely overstrained themselves, running down their gold and dollar reserves, wearing out their domestic machinery, and (despite an extraordinary mobilization of their resources and population) becoming increasingly dependent upon American munitions, shipping, foodstuffs, and other supplies to stay in the fighting. While its need for such imports had risen year by year, its export trade had withered away— by 1944 it was a mere 31 percent of the 1938 figure. When the Labor government entered office in July 1945, one of the first documents it had to read was Keynes’s hair-raising memorandum about the “financial Dunkirk” which the country was facing: its colossal trade gap, its weakened industrial base, its enormous overseas establishments, meant that American aid was desperately needed, to replace the cutoff Lend-Lease. Without that help, indeed, “a greater degree of austerity would be necessary than we have experienced at any time during the war. … ”71 Once again, as happened after the First World War, the goal of creating a home fit for heroes would have to be modified. But this time, it was impossible to believe that Britain was still at the center of the world politically.

十分明显的事实是,为了保证取得战争的胜利,英国人严重地损耗了自己的实力,美元储备和黄金储备消耗殆尽,国内机器设备磨损严重、破烂不堪。英国虽然对其资源和人口进行了超限度动员,但仍然日益依靠美国的武器弹药、航运、食品和其他物资来维持战争。英国的这种进口需求一年高于一年,但其出口却不断萎缩,到1944年,英国的出口量只相当于1938年的31%。当工党政府在1945年7月上台执政时,在它不得不处理的第一批文件中,有一份就是凯恩斯关于国家正在面临的“财政上的敦刻尔克”的备忘录。这是一份令人毛骨悚然的报告,它指出:英国贸易逆差巨大,工业基础已受到削弱,驻海外机构过于庞大,这一切意味着英国急切需要美国提供援助,以取代行将中断的“租借”物资的供应。如果没有美国的援助,“我们[2]就须采取比战时任何时期都要严厉的紧缩措施”。这样,英国便又像第一次世界大战结束后那样,不得不修改其创造一个与英雄相称的家园的目标。但在这时,人们已不可能再相信英国仍处在世界政治中心的位置。

Yet, the illusions of Great Power status lingered on, even among Labor ministers intent upon creating a “welfare state. ” The history of the next few years therefore involved an earnest British attempt to grapple with these irreconcilables—improving domestic standards of living, moving to a “mixed economy,” closing the trade gap, and at the same time supporting a vastly extended array of overseas bases, in Germany, the Near East, and India, and maintaining large armed forces in the face of the worsening relations with Russia. As the detailed studies of the Attlee administration suggest,72 it was remarkably successful in many respects: industrial productivity rose, the trade gap narrowed, social reforms were enacted, the European scene was stabilized. The Labor government also found it prudent to withdraw from India, to pull out of the chaos in Palestine, and to abandon the guarantees to Greece and Turkey, so that it was relieved of at least some of its more pressing overseas burdens. On the other hand, that economic recovery had itself depended upon the large loan Keynes had negotiated in Washington in 1945, upon the further massive support which came via Marshall Plan aid, and upon the stilldevastated state of most of Britain’s commercial rivals; it was, therefore, a delicate and conditional economic revival. Equally suspect, over the longer term, was the success of the British withdrawals of 1947. It certainly shed intolerable burdens; but that strategical “fancy footwork” was postulated on the assumption that in abandoning certain regions, Britain could relocate its bases to accord more with its real imperial interests—the Suez Canal rather than Palestine, Arabian oil rather than India. At this stage, there certainly was no intention in Whitehall of giving up the rest of the dependent empire, which in economic terms was more important to Britain than ever before. 73 Only further shocks and the rising costs of hanging on would later force another reappraisal of Britain’s place in the world. In the meantime, however, it would remain an overextended but still powerful strategical entity, dependent upon the United States for security and yet also that country’s most useful ally—and an important strategic collaborator—in a world dividing into two large power blocs. 74

然而,英国却迟迟未能摆脱大国地位的幻觉,甚至那些想创建“福利国家”的工党大臣们也未能摆脱。只是在以后的几年中,英国才认真打算解决下述不可调和的问题:提高生活水平,向“混合型经济”发展,减少贸易逆差,与此同时还要维持在海外散布极广的基地(在德国、近东和印度),保持一支庞大的军队以应付与苏联日益恶化的关系。对艾德礼政府的详尽研究表明,艾德礼政府在许多方面取得了令人瞩目的成就。例如,提高了生产率,减少了贸易逆差,实施了社会改革计划,稳定了欧洲的局势。工党政府还谨慎地撤出了印度,摆脱了巴勒斯坦动乱的困扰,放弃了对希腊和土耳其的保证,这样,它至少在一定程度上解除了某些越来越沉重的海外负担。另一方面,英国经济之所以能恢复,还因为凯恩斯1945年在华盛顿通过谈判取得了巨额贷款,通过“马歇尔计划”进一步获得了大量的援助,以及英国的大多数商业对手此时满目疮痍,无暇他顾。因此,英国经济的复苏是一种微妙而有条件的恢复。从长远看,英国在1947年成功的撤退,同样也有令人怀疑之处。那种撤退是卸掉了无法承受的包袱,但是,这一战略上的“想象的步法”却是以这样的设想为依据的:英国放弃某些地区后,可以根据帝国的真正利益(是苏伊士运河而不是巴勒斯坦,是阿拉伯的石油而不是印度)来重新安排自己的基地。在这时,白厅肯定还不打算放弃依附其帝国的其余地区,因为从经济上看,这些地区对英国比以往更加重要,只是后来世界进一步发生震动和把自己拴在这些地区的代价日益增大,才迫使英国对其在世界上的地位又一次进行了估价。然而,与此同时,英国仍是一个虽承担义务过多但仍很强大的战略实体,在分裂成两大势力集团的世界中,英国要在安全方面依靠美国,美国则成为英国最有用的盟国和重要的战略合作者。

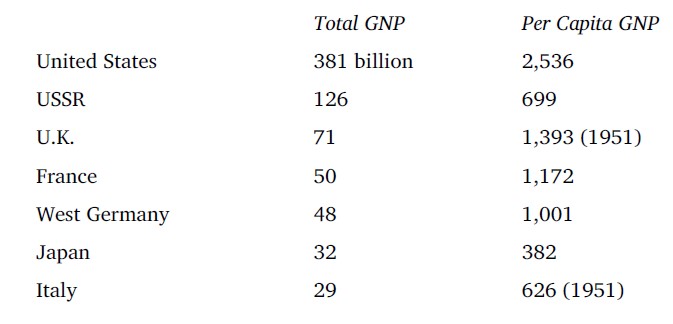

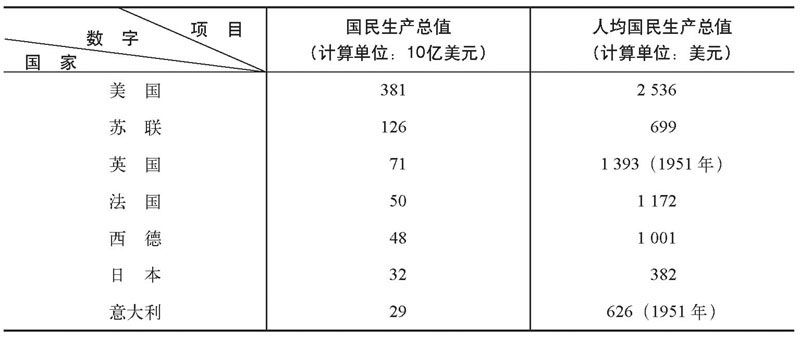

All the efforts of British and French governments to the contrary, however, there was no doubt about “the passing of the European age. ” While the U. S. GNP had surged by more than 50 percent in real terms during the war, Europe’s as a whole (but minus the Soviet Union) had fallen by about 25 percent. 75 Europe’s share of total world manufacturing output was lower than at any time since the early nineteenth century; even by 1953, when most of the war damage had been repaired, it possessed only 26 percent of the whole (compared with the United States’ 44. 7 percent). 76 Its population was now only about 15–16 percent of the total world population. In 1950 its per capita GNP was only about one-half of the United States’; moreover, the Soviet Union had by then significantly closed the gap, so that the total GNP of the powers was as shown in Table 36.

但是,英法两国政府的所有努力无疑都不能挽回“欧洲时代结束”的趋势。在战争中,美国的国民生产总值实际增长了50%以上,而整个欧洲(不包括苏联)却下降了25%。欧洲在世界制造业总产量中所占的比重,低于19世纪初期以来的任何时期;甚至到1953年绝大部分制造业从破坏中恢复过来之后,整个欧洲所占的比重也只有26%(而美国达44.7%)。欧洲的人口只占世界总人口的15%~16%。在1950年,欧洲的人均国民生产总值仅及美国的一半。但是,苏联却大大缩小了与美国的差距(关于各大国国民生产总值情况,见表36)。

Table 36. Total GNP and per Capita GNP of the Powers in 195077

表36 1950年各大国国民生产总值与人均国民生产总值一览表

(in 1964 dollars)

(以1964年的美元价格计算)

This eclipse of the European powers was reflected even more markedly in military personnel and expenditures. In 1950, for example, the United States spent $14. 5 billion on defense and had 1. 38 million military personnel, while the USSR spent slightly more ($15. 5 billion) on its far larger armed forces of 4. 3 million men. In both respects, the superpowers were far ahead of Britain ($2. 3 billion; 680,000 personnel), France ($1. 4 billion; 590,000 personnel), and Italy ($0. 5 billion; 230,000 personnel), and of course Germany and Japan were still demilitarized. The Korean War tensions saw quite significant increases in the defense spending of the middleweight European powers in 1951, but they paled by comparison with the expenditures of the United States ($33. 3 billion) and USSR ($20. 1 billion). In that year alone, the defense expenditures of Britain, France, and Italy combined were less than one-fifth of the United States’ and less than one third of the USSR’s; and their combined military personnel was one-half of the United States’ and one-third of Russia’s. 78 In both relative economic strength and in military power, the European states seemed decidedly eclipsed.

欧洲大国的黯然失色更加明显地表现在兵员和军费开支上。例如,1950年,美国的军费开支是145亿美元,拥有138万军事人员;苏联的军费开支略多(155亿美元),而其武装力量却极为庞大,共有430万人。在这两方面,超级大国远远超过英国(23亿美元、68万人)、法国(14亿美元、59万人)和意大利(5亿美元、23万人);当然,德国和日本当时还没有武装。由于朝鲜战争的紧张局势,欧洲中等强国在1951年大大增加了自己的防务开支,但与美国和苏联相比,仍显得苍白无力(美国达333亿美元,苏联达201亿美元)。在那一年,英国、法国和意大利三国军费开支的总和还不到美国的1/5、苏联的1/3;其军事人员总数不到美国的一半、苏联的1/3。无论是在经济力量上,还是军事实力上,欧洲国家都是大势已去了。

Such an impression was, if anything, heightened by the coming of nuclear weapons and long-range delivery systems. It is clear from the record that many of the scientists working on the A-bomb were acutely aware that they were reaching toward a watershed in the entire history of warfare, weapon systems, and man’s capacity for destruction; the successful test at Alamogordo on July 16, 1945, confirmed to the observers that “there had been brought into being something big and something new that would prove to be immeasurably more important than the discovery of electricity or any of the other great discoveries which have affected our existence. ” When the “strong, sustained, awesome roar which warned of doomsday”79 was repeated in the actual carnage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there could be no further doubt of the weapon’s power. Its creation left American decision-makers wrestling with the many practical consequences for the future. How did it affect conventional warfare? Should it be used immediately at the outset of war, or as a weapon of last resort? What were the implications, and potentialities, of developing bigger (H-bombs) and smaller (tactical) forms of nuclear weapons? Should the knowledge be shared with others?80 It also undoubtedly gave a boost to the already existing Soviet development of nuclear weapons, since Stalin put his formidable security chief, Beria, in charge of the atomic program on the day after Hiroshima. 81 Although the Russians were clearly behind at this time, in the creation of both bombs and delivery systems, they caught up much faster than the Americans estimated they would. For some years after 1945, it seems fair to assume that the American nuclear advantage helped to “balance out” the Russian preponderance in conventional forces. But it was not long, certainly in the history of international relations, before Moscow began to catch up and thus to prove its own claim that the United States’ monopoly of this weapon had been only a passing phase. 82

核武器和远程投射系统的出现,进一步扩大了人们对欧洲衰落的印象。记录表明,许多从事原子弹研制工作的科学家都清楚地知道,他们所从事的研究在人类全部战争史、武器史和人类摧毁能力方面,具有划时代的意义。1945年7月16日在阿拉莫戈多的成功试验,证实了他们的看法:“一种巨大、全新的东西出现了;它对我们生存所产生的影响比电的发现和其他一切伟大发现都重要得多。”当广岛和长崎接连出现“世界末日般令人心惊胆战的连续巨响”,全城横尸遍地时,没有人再怀疑核武器的威力了。原子弹的出现使美国决策人对许多有关未来的实际后果进行了深思:原子弹对常规战争有何影响?在战争一开始就应使用原子弹,还是应把它当作撒手锏使用?研制更大的核武器(氢弹)和较小的核武器(战术核武器)的意义和潜力如何?有关原子弹的知识是否应该与他人分享?斯大林在广岛遭到原子弹轰炸后的第二天就派其无所不能的秘密警察头子贝利亚负责原子弹的研制工作。这说明,美国人的成就肯定推动了苏联已在进行的核武器研制工作。虽然苏联这时在原子弹和发射系统的研制方面处于明显的落后状态,但他们的追赶速度要大大高于美国人的估计。在1945年后的几年中,人们有理由设想,美国的核优势有助于“抵消”苏联人的常规部队优势。但是,在国际关系史中,莫斯科没用几年时间就开始赶上美国,证明了自己的论断:美国对核武器的垄断仅仅是一闪即过的阶段。

The coming of atomic weapons transformed the “strategical landscape,” since they gave to any state possessing them the capability of mass indiscriminate destruction, even of mankind itself. Much more narrowly, and immediately, the advent of this new level in weapons technology put increased pressure upon the traditional European states to catch up—or admit that they were indeed relegated to second-class status. Of course, in the case of Germany and Japan, and the economically and technologically weakened Italy, there was no prospect of joining the nuclear club. But to the government in London, even when Attlee replaced Churchill, it was inconceivable that the country should not possess those weapons, both as a deterrent and because they “were a manifestation of the scientific and technological superiority on which Britain’s strength, so deficient if measured in sheer numbers of men, must depend. ”83 They were seen, in other words, as a relatively cheap way of retaining independent Great Power influence—a calculation which, shortly afterward, appealed equally to the French. 84 Yet, however attractive that logic appeared to be, it was weakened by practical factors: that neither state would possess the weapons, and delivery systems, for some years; and that their nuclear arsenals would be minor compared with those of the superpowers, and might indeed be made obsolete by a further leap in technology. For all the ambitions of London and Paris (and, later on, China) to join the nuclear club, this striving during the early post-1945 decades was somewhat similar to the Austro- Hungarian and Italian efforts to possess their own Dreadnought-type battleships prior to 1914. It was, in other words, a reflection of weakness rather than strength.

原子弹的问世改变了世界的“战略形势”,因为拥有核武器的所有国家都具有大规模的不分青红皂白的破坏能力,甚至有毁灭人类的能力。从狭义和直接意义上看,这种新武器技术的出现,增加了对各欧洲古老国家的压力:要么奋起直追,要么甘愿沦为二流国家。当然,就德国、日本以及在经济和技术上都很脆弱的意大利来说,它们没有希望加入核俱乐部,但伦敦政府则不然。早在艾德礼接替丘吉尔时,英国就没想不应该获得这种武器。这不仅因为核武器是一种威慑手段,还因为核武器是“英国科学与技术优势的集中表现,是人口较少的英国的力量得以存在的依靠”。换言之,核武器被视为一种保持独立大国地位的较为廉价的手段。法国不久也步英国的后尘,作了同样的考虑。但是,这种想法无论在逻辑上多么吸引人,在实践上却有三个不利因素:一是两国在几年内都不会获得核武器及其投射系统;二是两国的核武库与超级大国的相比无足轻重;三是随着技术的飞速发展,他们的核武器将会变得陈旧落后。在1945年后的数十年间,伦敦、巴黎想加入核俱乐部的雄心和为此所作的努力,犹如1914年前奥匈帝国和意大利要拥有自己的“无畏”级战列舰一样。换句话说,这不是力量的反映,而恰恰是虚弱的反映。

The final element which seemed to emphasize that the world must now be viewed, strategically and politically, as bipolar rather than in its traditional multipolar form was the heightened role of ideology. To be sure, even in the age of classical nineteenth-century diplomacy, ideological factors had played a part in policy—as the actions of Metternich, Nicholas I, Bismarck, and Gladstone amply testified. This seemed much more the case in the interwar years, when a “radical right” and a “radical left” arose to challenge the prevailing assumptions of the “bourgeois-liberal center. ” Nonetheless, the complex dynamics of multipolar rivalries by the late 1930s (with British Tories like Churchill wanting an alliance with Communist Russia against Nazi Germany, and with liberal Americans wanting to support Anglo-French diplomacy in Europe but to dismantle the British and French empires outside Europe) made difficult all attempts to explain world affairs in ideological terms. During the war itself, moreover, differences on political and social principles could be subsumed under the overriding need to combat fascism. Stalin’s suppression of the Communist International in 1943 and the West’s admiration for the Russian resistance to Operation Barbarossa also seemed to blur earlier suspicions—especially in the United States, where Life magazine in 1943 airily claimed that the Russians “look like Americans, dress like Americans and think like Americans,” and the New York Times a year later declared that “Marxian thinking in Soviet Russia is out. ”85 Such sentiments, however naive, help to explain the widespread American reluctance to accept that the postwar world was not living up to their vision of international harmony—hence, for example, the pained and angry reactions of many to Churchill’s famous “Iron Curtain” speech of March 1946. 86

要强调的最后一点是,现在世界在战略上和政治上已从传统的多极世界变成了两极世界,在这样的世界中,意识形态的作用得到了加强。其实,早在19世纪的古典外交中,意识形态就在外交政策中发挥过作用,梅特涅、尼古拉一世、俾斯麦和格莱斯顿的行动充分证明了这一点。意识形态的作用在两次大战之间的年代里更加明显地表现了出来。当时“极右”和“极左”势力兴起,向居统治地位的“中产阶级—自由中心”的流行观念发出了挑战。但到20世纪30年代末,由于多级化竞争对手力量关系错综复杂(在英国,像丘吉尔等保守党人希望与共产主义的苏联结盟,反对纳粹德国;自由主义的美国人虽然支持欧洲的英、法民主国家,但却想肢解英、法在欧洲以外的领地),人们难以用意识形态来解释国际事务。而且,在战争中,当务之急是同法西斯主义作斗争,政治和社会原则的分歧便不得不服从于这一最重要的任务。斯大林在1943年解散了共产国际;西方也十分赞赏俄国人对“巴巴罗萨行动”所做的抵抗。这似乎冲淡了他们原先的相互怀疑——尤其是在美国,《生活》杂志在1943年曾以轻松活泼的笔调写道:苏联人“长得像美国人,穿着像美国人,想法也像美国人”。《纽约时报》在一年后声称:“马克思的思想在苏联已经销声匿迹了。”这些情绪不管多么天真幼稚,但有助于向我们说明为什么那么多的美国人不愿接受以下事实:战后世界并非像他们想象的那样,生活在国际和谐之中。例如1946年3月丘吉尔著名的“铁幕演说”,就在许多美国人中引起了愤怒和痛苦的反应。

Yet, within another year or two, the ideological nature of what was now admitted to be the Cold War between Russia and the West was all too evident. The increasing signs that Russia would not permit parliamentary-type democracy in eastern Europe, the sheer size of the Russian armed forces, the civil war raging between Communists and their opponents in Greece, China, and elsewhere, and—last but by no means least—the growing fears of “the Red menace,” spy rings, and internal subversion at home led to a massive swing in American sentiment, and one to which the Truman administration responded with alacrity. In his “Truman Doctrine” speech of March 1947, occasioned by the fear that Russia would enter into the power vacuum created by Britain’s withdrawal of guarantees to Greece and Turkey, the president portrayed a world faced with a choice between two different sets of ideological principles:

但是,苏联和西方之间一两年后就出现了“冷战”,而“冷战”所具有的意识形态性质暴露无遗。越来越多的迹象表明,苏联人不会允许东欧出现议会式的民主;苏联还保持着庞大的军队;在希腊、中国及其他地区,共产党同其敌手正进行着内战;还有最后一点,但绝不是最不重要的一点,即人们对“红色威胁”恐惧的日益增加,苏联的间谍网以及国内颠覆活动,这一切促使美国公众的情绪发生了剧烈的变化,杜鲁门政府对此也断然做出了反应。由于担心苏联会进入英国撤销其对希腊、土耳其的保证后留下的力量真空,杜鲁门总统于1947年3月发表了“杜鲁门主义”的演说。在这篇演说中,杜鲁门描绘了当前世界必须抉择的两种截然不同的意识形态原则:

One way of life is based upon the will of the majority, and is distinguished by free institutions, representative government, free elections, guarantees of individual liberty, freedom of speech and religion and freedom from political oppression. The second way of life is based upon the will of a minority forcibly imposed on the majority. It relies upon terror and oppression, a controlled press, framed elections and the suppression of personal freedom. 87

一种生活方式是以大多数人的意志为基础的。它突出地表现为自由的制度、代议制政府、自由选举、保证个人自由、言论与宗教信仰自由和没有政治迫害。另一种生活方式则是以少数人的意志强加于大多数人为基础。它所依靠的是恐怖和迫害、对报纸的控制、指名选举和压制个人自由。

It would be the policy of the United States, Truman continued, “to help free people to maintain their institutions and their integrity against aggressive movements that seek to impose upon them totalitarian regimes. ” Henceforward, international affairs would be presented, in even more emotional terms, as a Manichean struggle; in Eisenhower’s words, “Forces of good and evil are massed and armed and opposed as rarely before in history. Freedom is pitted against slavery, lightness against dark. ”88

杜鲁门继续说:美国的政策就是“帮助自由的人民保持自己的制度及统一,反对企图将极权政权强加于他们的侵略行径”。此后,国际事务,用更加生动的话来说,犹如摩尼教徒正在进行的一场争斗;用艾森豪威尔的话来说,就是“正义力量和邪恶力量在历史上很少像现在这样聚集一堂、全副武装、相互抗争。以自由反对奴役,以光明反对黑暗”。

No doubt much of this rhetoric had a domestic purpose—and not just in the United States, but also in Britain, Italy, France, and wherever it was useful for conservative forces to invoke such language to discredit their rivals, or to attack their own governments for being “soft on Communism. ” What was also true was that it must have deepened Stalin’s suspicions of the West, which was swiftly portrayed in the Soviet press as contesting the Russian “sphere of influence” in eastern Europe, surrounding the Soviet Union with new foes on all sides, establishing forward bases, supporting reactionary regimes against any Communist influences, and deliberately “packing” the United Nations. “The new course of American foreign policy,” Moscow claimed, “meant a return to the old anti-Soviet course, designed to unloose war and forcibly to institute world domination by Britain and the United States. ”89 This explanation, in turn, could help the Soviet regime to justify its crackdown upon internal dissidents, its tightening grip upon eastern Europe, its forced industrialization, its heavy spending upon armaments. Thus, the foreign and domestic requirements of the Cold War could feed off each other, mutually covered by an appeal to ideological principles. Liberalism and Communism, being both universal ideas, were “mutually exclusive”;90 this permitted each side to understand, and to portray, the whole world as an arena in which the ideological quarrel could not be separated from power-political advantage. One was either in the American-led bloc or the Soviet one. There was to be no middle way; in an age of Stalin and Joe McCarthy, it was imprudent to think that there could be. This was the new strategical reality, to which not merely the peoples of a divided Europe but also those in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and elsewhere would have to adjust.

毫无疑问,这类语言好多都有其对国内目的,不仅美国如此,英国、意大利、法国及其他各国也都一样。保守势力可以使用这类语言使对手威信扫地,或者攻击自己的政府对“共产主义软弱无力”。但这样一来又肯定加深了斯大林对西方的怀疑。苏联报刊很快就说西方正在觊觎苏联在东欧的“势力范围”,在苏联四周树立新的敌人,建立前进基地,以包围苏联;西方还支持反动政权反对共产主义力量,有意在联合国“结帮拉派”。莫斯科声称:“美国对外政策的新方针,是过去反苏政策的翻版,其目的是发动战争,以武力建立一个由英国和美国统治的世界。”苏维埃政权便以此为借口,清除国内异己分子,加强对东欧的控制,实施强制性的工业化,大量增加军费开支。因此,双方都在加剧“冷战”,都用意识形态原则来掩盖自己对内和对外政策的需要。自由主义和共产主义是两个世界性的思想体系,互相“排斥”,水火不相容。因此,双方都把世界视为一个舞台,在这个舞台上,意识形态的争吵不可能与权力—政治利益相分离。一个国家不站在美国领导的阵营内,便站在苏联领导的阵营内,不存在中间道路。在斯大林和麦卡锡时代,那种走中间道路的想法是很不明智的。这就是新的战略现实,不仅被分裂的欧洲各国人民要适应它,而且亚洲、中东、非洲、拉丁美洲及其他地区的人民也必须做出调整,使自己适应它。