The Cold War and the Third World

“冷战”与第三世界

As it turned out, a large part of international politics over the following two decades was to concern itself with adjusting to that Soviet-American rivalry, and then with its partial rejection. In the beginning, the Cold War was centered upon remaking the boundaries of Europe. Underneath, therefore, it was still to do with the “German problem,” since the resolution of that issue would in turn determine the amount of influence which the victorious Powers of 1945 would exert over Europe. The Russians had undoubtedly suffered more than any other country from German aggressions in the first half of the twentieth century, and, reinforced by Stalin’s own paranoid demand for security, they were determined to permit no repetitions in the second half. Promoting the Communist world revolution was a secondary but not unconnected consideration, since Russia’s strategic and political position was most likely to be enhanced if it could create other Marxist-led states which looked to Moscow for guidance. Such considerations, much more than any centuries-old drive toward warm-water ports, probably ordered the Soviet policy in the post-1945 world, even if it left open the detailed solution of the various issues. There was, in the first place, therefore, a determination to undo the territorial settlements of 1918–1922, with “roundings-off” for strategical purposes; as noted above, this meant the reassertion of Russian control over the Baltic states, the pushing westward of the Polish-Russian border, the elimination of East Prussia, and the acquisition of territories from Finland, Hungary, and Rumania. Little of this worried the West; indeed, much of it had been agreed to during the war. What was more perturbing was the Russian indications of how they intended to ensure that the formerly independent countries of east-central Europe would contain regimes “friendly to Moscow. ”

正如以后所证实的,在第二次世界大战后的20年中,国际政治的主要任务是进行自我调整,以适应苏美对抗的新形势;而次要任务则是反对苏美对抗。起初,“冷战”主要围绕重新划分欧洲国界进行。归根结底,“冷战”仍系于“德国问题”,这一问题的解决方式将决定1945年的战胜国对欧洲影响的大小。毫无疑问,20世纪上半叶德国侵略对苏联造成的损失,比对其他任何国家都大。苏联人决心不再让20世纪上半叶发生的事件在下半叶重演,且这一观念由于斯大林坚决要求得到安全保障而有所强化。苏联人考虑的第二个问题是,使世界共产主义革命的形势得到进一步发展。这是因为,如果要求莫斯科指导的更多的马克思主义者领导的国家得以建立,苏联的政治和战略地位很可能得到提高。这些比从前要求得到不冻港的更高层次上的考虑,可能是1945年后苏联制定政策的依据,尽管还有许多问题有待于它彻底解决。因此,苏联首先决心废除1918~1922年签订的各项领土协定,战略目的是“解围”。如前所述,这等于让苏联人重新获得对波罗的海各国的控制权,使波苏边界西移,使东普鲁士从此消亡,苏联从芬兰、匈牙利和罗马尼亚得到部分领土。这些并没使西方担心,其中许多的确是在战时西方就已同意的。使人不安的是,苏联想在中、东欧的独立国家中建立“亲莫斯科”政权。

In this respect, the fate of Poland was a harbinger of what would occur elsewhere, although it was the more poignant because of Britain’s 1939 decision to fight for that country’s integrity, and because of the Polish contingents (and government in exile) which had operated in the West. The discovery of the mass grave of Polish officers at Katyn, the Russian disapproval of the Warsaw uprising, Stalin’s insistence on altering Poland’s boundaries, and the appearance of a pro-Moscow faction of Poles at Lublin made Churchill in particular suspicious of Russia’s intentions; within another few years, with the installation of a puppet regime and the virtual elimination of any pro-western Poles from positions of power, those fears were realized. 91

在这一方面,波兰的命运预示着其他国家的命运,虽然这对西方的刺激较大,因为1939年英国就决心为保卫波兰的领土完整而战,且波兰军队(及流亡政府)战时也在为西方作战。在卡滕发现埋葬波兰军官的大坟场,苏联人对华沙起义的非难,斯大林坚持要改变波兰边界,以及亲莫斯科的波兰人派别在卢布林的出现,这一切使丘吉尔对苏联人的企图怀疑至深。几年之后,苏联人便扶植起一个傀儡政权,并在各级权力机构中清除了所有亲西方的波兰人。这使西方人的担心得到了证实。

Moscow’s handling of the Polish issue related to the “German problem” in all sorts of ways. Territorially, the westward adjustment of the boundaries not only reduced the size of German lands (as did the swallowing-up of East Prussia), it also gave the Poles an incentive to oppose any future German revision of the Oder-Neisse line. Strategically, the Russian insistence upon making Poland a secure “buffer zone” was intended to ensure that there could be no repetition of Germany’s 1941 attack; it was logical, therefore, for Moscow to insist upon determining the fate of the German people as well. Politically, the support of the “Lublin” Poles was paralleled by the grooming of German Communists in exile to play a similar role when they returned to their homeland. Economically, Russia’s exploitation of Poland and its eastern European neighbors was a foretaste of the stripping of German assets. When, however, it became obvious to Moscow that it would be impossible to win the German people’s goodwill while systematically reducing them to penury, the assetstripping ceased and Molotov’s tone became much more encouraging. But those tactical shifts were of less importance than the obvious message that Russia intended to have a, if not the, major say in deciding Germany’s future. 92

莫斯科在处理波兰问题时在许多方面都涉及到“德国问题”。从领土上看,波兰边界的西移不仅缩小了德国的疆域(东普鲁士已被吞并),还使波兰人在阻止德国将来改变奥得-尼斯一线的边界方面处于有利地位。从战略上看,苏联坚持使波兰成为一个安全“缓冲地带”的目的是,确保自己不再遭受德国“1941年式”的进攻。因此,莫斯科坚持要同时决定德国人民的命运也是合乎逻辑的。从政治上看,苏联在支持“卢布林”波兰人的同时,还对流亡他乡的德国共产党人进行了培训,以便让他们回到祖国后起同样的作用。从经济上看,苏联对波兰及其他东欧邻国进行剥削后,还想掠夺德国的财富。但当莫斯科清楚地看到,如果使德国人变成穷汉就无法赢得他们的友谊时,便停止了掠夺活动,莫洛托夫讲话的语调也变得比较中听了。不过,这些战术上的变化并不重要。重要的是,在决定德国未来的问题上,苏联要求有重要发言权,如果不是最后决定权的话。

Both in the Polish and the German cases, then, Russian policy was bound to clash with that of the West. Politically and economically the Americans, British, and French desired free-market ideas and democratic elections to be the norm throughout Europe (although London and Paris clearly wished the state to occupy a larger place than the laissez-faire Americans preferred). Strategically, the West was just as determined as Moscow to prevent any revival of German militarism, and the French especially were to worry about that until the mid-1950s; but none of them wanted to see the Wehrmacht’s domination of Europe merely replaced by the Red Army’s. And although both the French and the Italian governments after 1945 contained Communists, there was a deep mistrust of Marxist parties gaining real power anywhere—a feeling confirmed by the steady elimination of non-Communist parties in eastern Europe. Although there were still voices hoping for a reconciliation between Russia and the West, the fact was that their respective aims clashed in all manner of ways. If one side’s program succeeded, the other would feel threatened; in that sense, at least, the Cold War seemed inevitable, until both sides agreed to compromise on their universalist assumptions.

在波兰和德国问题上,苏联的政策肯定要与西方的政策发生冲突。在政治上和经济上,美国人、英国人和法国人都要求整个欧洲执行自由市场政策,都进行民主选举(虽然英国人和法国人比自由放任的美国人更主张国家有较大的权力)。从战略上看,西方和苏联一样,也决心防止德国军国主义的重新复活。特别是法国人对此一直忧心忡忡,直至20世纪50年代中期。但是,他们都不希望看到苏联红军取代德国国防军统治欧洲。虽然1945年后法国和意大利政府仍能包容共产党人,但对掌权的马克思主义政党,西方人有一种非常不信任的情绪。这种情绪因东欧各国逐步取缔了非共产主义政党而变得更加强烈。尽管仍有人呼吁苏联和西方和解,但事实是,它们各自的目标在各个方面都不一致。假如一方的一项计划获得成功,另一方就感觉受到了威胁。至少从这个意义上讲,“冷战”是不可避免的,并且一直会持续到双方都同意在所有问题上进行和解。

For that reason, a step-by-step account of the escalation of the tensions is not necessary here;93 it would have the same relevance to this analysis of the evolving dynamics of world power as would, say, a detailed account of Metternich’s diplomacy in an earlier chapter. The chief features of the Cold War after 1945 are, however, worthy of examination, since they have continued to affect the conduct of international relations to this day.

有鉴于此,在这里详述东西方紧张关系的逐步升级实无必要,就像在前面的一章中在分析世界力量对比的变化时再详述梅特涅的外交活动一样。然而,1945年后“冷战”的主要特点则值得审视,因为至今它们仍然影响着各国处理国与国之间关系的方式。

The first of these was the intensification of the “split” between the two blocs in Europe. That this bifurcation had not occurred immediately in 1945 was understandable: the chief tasks then for the Allied occupation forces, and for the “successor” parties which emerged out of hiding and exile once the Germans had left, were pressing administrative ones—restoring communications and utilities, getting foodstuffs to the cities, housing the refugees, tracking down war criminals. Much of this led to a blurring of ideological positions: in the occupied zones of Germany, the Americans found themselves quarreling as much with the French as with the Russians; in national assemblies and cabinets being formed across Europe, Socialists sat alongside Communists in the east, Communists alongside Christian Democrats in the west. But by late 1946 and early 1947, the gap was widening and becoming more publicized: various plebiscites and regional elections in the German zones were showing “the political complexion of West Germany … beginning to differ markedly from that of East Germany”;94 the steady elimination of any non- Communist elements in Poland, Bulgaria, and Rumania was mirrored by the internal political crisis in France in April 1947, when the Communists were forced to resign from the government. A month after, the same happened in Italy. In Yugoslavia, Tito’s political domination (in place of the Allied wartime agreements about shared power) was interpreted by the West as a further step in Moscow’s planned advance. These disagreements, together with the Soviet Union’s unwillingness to join the IMF and International Bank, especially disturbed those Americans who had hoped to preserve good relations with Moscow after the war.

“冷战”的第一个特点是,欧洲两大国家集团进一步“分裂”。这种“分裂”在1945年没有马上发生是可以理解的。当时,同盟国占领军和“接班”政党(它是由在德国人离开后从秘密转为公开的党员和流亡回国的党员组成的)的主要任务是,处理迫在眉睫的行政事务,如恢复交通、通信等公用事业,往城市运送食品,为难民提供住房,以及追捕战争罪犯等。在进行上述工作时,意识形态的界线是模糊的:在德国占领区,美国人发现,他们与法国人的争吵同与苏联人的一样多;在欧洲各国新成立的国民议会和内阁中,社会党人与共产党员坐在一起(在东欧),或共产党员与基督教民主党人坐在一起(在西欧)。但是,到1946年底和1947年初,两种意识形态之间的鸿沟便开始扩大,并且日益公开化:在德国各地进行的公民投票和地方选举表明,“联邦德国的政局……与民主德国的政局之间开始出现明显差异”。在波兰、保加利亚和罗马尼亚,非共产党人被迫逐渐离开领导岗位。这导致1947年4月法国国内的政治危机,即共产党人被迫退出政府。一个月后,意大利发生了类似事件。在南斯拉夫,铁托实行的政治统治(战时各同盟国达成的协议规定实行分权统治),在西方人看来,是莫斯科预谋扩张的又一步骤。这些分歧,再加上苏联不愿加入国际货币基金组织和世界银行,使那些希望在战后与莫斯科保持友好关系的美国人大为不安。

It was only a modest leap in assumptions, therefore, for the West to suspect that Stalin also planned to acquire control in western and southern Europe when the circumstances were right and, indeed, to hurry those circumstances along. This was unlikely to occur by outright military force, although the increasing Russian pressure upon Turkey was worrying, and prompted Washington to station a naval task force in the eastern Mediterranean by 1946; rather, it might come about through the ability of Moscow’s minions to take advantage of the continued economic dislocation and political rivalries caused by the war. The Greek Communist revolt was seen as one sign of this; the Communist-supported strikes in France another. The Russian bids to woo German public opinion were suspicious; so, too, if one really wanted to worry about things, was the strength of the Communists in northern Italy. Historians of each of those movements are nowadays more skeptical of how much they could have been controlled by a Moscow-conceived “master plan. ” The Greek Communists, Tito, and Mao Tse-tung cared most about their local foes, not a global Marxist order; and the leaders of Communist parties and trade unions in the West had to respond, first and foremost, to their followers’ mood. On the other hand, a gain for Communism in any of those countries would undoubtedly have been welcome to Russia, provided it did not lead to a major war; and it is easy to understand why, at the time, Soviet experts like George Kennan were sympathetically heard when they argued the case for “containing” the Soviet Union.

因此,在西方人的思想中产生了一个不大不小的飞跃,即怀疑斯大林也打算在条件成熟时控制西欧和南欧,并且的确在加速创造这些条件。这种情况的发生,不会是直接动用武力的结果(尽管苏联对土耳其施加日益增大的压力不仅令人担忧,而且还致使华盛顿1946年在东地中海部署了一支海军特混编队),而很可能由莫斯科的代理人利用战争造成的经济混乱和政治纷争而促成。这种迹象之一是希腊共产党的革命;迹象之二是法国共产党支持的大罢工。苏联企图取悦德国公众舆论的做法受到怀疑,意大利北部共产党力量的壮大也令人担忧(如果人们自寻烦恼.对任何事情都会忧心忡忡)。研究上述情况的历史学家们现在更不相信,它们与莫斯科制订的“总计划”有直接联系。希腊共产党、铁托最关心的是本地区的敌情,而不是建立世界马克思主义体系。西方国家的共产党和工会领导人,首先要考虑他们的追随者的情绪。另一方面,如果在不发生大规模战争的情况下,共产党在西方任何国家上台,苏联人当然高兴。所以,当乔治·凯南等苏联问题专家呼吁“遏制”苏联时,在思想上引起了人们的共鸣,就不难理解了。

Among all of the varied elements of the fast-evolving “strategy of containment,”95 two stood out. The first, admitted by Kennan to be negative in nature although increasingly preferred by the military chiefs as offering more solid guarantees of stability, was to indicate to Moscow those regions of the globe which the United States “cannot permit … to fall into hands hostile to us. ”96 Such states would, therefore, be given military support to build up their powers of resistance; and a Soviet attack on them would be regarded virtually as a casus belli. Much more positive, however, was the American recognition that resistance to Russian subversion was weakened because of “the profound exhaustion of physical plant and of spiritual vigor” caused by the Second World War. 97 The most crucial component of any long-term containment policy would therefore be a massive program of U. S. economic aid, to permit the rebuilding of the shattered industries, farms, and cities of Europe and Japan; for that would not only make the latter far less likely to be tempted by Communist doctrines of class struggle and revolution, it would also help to readjust the power balances in America’s favor. If, to use Kennan’s very plausible geopolitical argument, there were only “five centers of industrial and military power in the world which are important to us from the standpoint of national security”98— the United States itself, its rival the USSR, Great Britain, Germany and central Europe, and Japan—then it followed that by keeping the three last-named areas in the western camp and by building up their strength, there would be a resultant “correlation of forces” which would ensure that the Soviet Union was permanently inferior. Equally obvious, this strategy would be regarded with profound suspicion by Stalin’s Russia, especially since it included the restoration of its two recent enemies, Germany and Japan.

在迅速制定出来的“遏制战略”的众多要素中,有两个要素最为引人注目。第一个是,向莫斯科表明,地球上哪些地区美国“不允许……落入敌手”(这样做凯南认为有消极作用,却受到了越来越多的军事领导人的赞成,因为他们认为这可确保国际战略格局更加稳定)。因此,位于这些地区的国家将在美国的军事援助下,提高自己的防御能力。苏联对这些国家发动进攻,美国就与苏联开战。第二个比较有积极意义的要素是,美国看到,抵御苏联颠覆的力量已经受到削弱,因为第二次世界大战严重地损耗了西方的物质资源和精神元气。所以,各项长远遏制政策最重要的内容是:美国大规模执行经济援助计划,以帮助西欧各国和日本重建受到严重破坏的工业、农业和城市。这样做,不仅可削弱共产主义的阶级斗争理论和革命理论对西欧和日本的影响,还有助于使世界力量对比向着有利于美国的方向发展。凯南似乎很有道理的地缘政治论认为,从维护国家安全的角度看,世界有五大工业和军事力量中心对我们至关重要,即美国本身、其对手苏联、英国、德国与中欧、日本。如果真的如此,那么,只要使后三者留在西方阵营,并使其实力得到增强,就会建立可使苏联永远处于劣势的综合“力量对比”。同样显而易见的是,斯大林的苏联将对这一战略深感疑虑,因为它包括复活苏联的两个最近的敌人——德国和日本。

Once again, therefore, an exact chronology of the various steps taken by each side during and after the “watershed year” of 1947 is less important than the general consequences. The U. S. replacement of the British guarantees to Greece and Turkey —symbolically, a transfer of responsibilities from the former global policeman to the rising one, and as much a part of London’s logic as of Washington’s99—was justified by Truman in terms of a “doctrine” which had no regional limitations. In the European context, however, the open American willingness “to help free peoples maintain their institutions” could be linked to the earnest discussions which were taking place about how to deal with the widespread economic distress, the food shortages, and the scarcity of coal which were afflicting the continent. The American administration’s solution—the so-called Marshall Plan for massive aid “to place Europe on its feet economically”—was deliberately presented as an offering to all European nations, whether Communist or not. But whatever the attractions of receiving that aid may have been to Moscow, it did involve joint cooperation with western Europe, just at a time when the Soviet economy had returned to the most rigid forms of socialization and collectivization; and it took no genius to see that the raison d’être for the plan was to convince Europeans everywhere that private enterprise was better able to bring them prosperity than Communism. The result of Molotov’s walkout from the Paris talks on the plan, and of the Russian pressure upon Poland and Czechoslovakia not to apply for aid, was that Europe became much more divided than before. In western Europe, boosted by the billions of dollars of American aid (especially to the larger states of Britain, France, Italy, and West Germany), economic growth shot ahead, integrated into a North Atlantic trading network. In eastern Europe, Communist controls were being tightened. The Cominform was set up in 1947, as a sort of reconstituted and only half-disguised Communist International. The pluralist regime in Prague was ended by a Communist coup in 1948. While Tito’s Yugoslavia managed to escape from Stalin’s claustrophobic embrace, other satellites found themselves subject to purges, and in 1949 they were forced to join Comecon (Council of Mutual Economic Assistance), which, far from being a Soviet Marshall Plan was “simply a new piece of machinery for milking the satellites. ”100 Churchill may have been a little premature in his “Iron Curtain” description of 1946; two years later, his words seemed realized.

因此,我们可以再一次说,逐个评述双方于1947年这一“分水岭年”及其以后采取的各项措施,不如论述一下最后的总结果更有意义。美国取代英国对希腊和土耳其承担义务(这表示前世界警察将其职责交给了新兴的世界警察,伦敦的逻辑和华盛顿的逻辑基本相同),从而使适用于世界任何地区的“杜鲁门主义”的出笼有了理论依据。因而在欧洲,美国热心“帮助自由民族维护它们的制度”的具体表现是,与西欧人认真地探讨如何解决困扰欧洲大陆的经济萧条、食品短缺、煤炭不足等问题。美国政府对这些问题的解决办法是,根据所谓的“马歇尔计划”大量提供援助,帮助欧洲各国实现经济自主。美国审慎地宣布,它的援助将提供给欧洲所有国家,既包括非社会主义国家,也包括社会主义国家。但是,不管美国的援助对莫斯科是否有吸引力,苏联与西欧的确进行过合作。正当东西方进行经济合作时,苏联采用了国有化和集体化这种没有一点儿弹性的经济体制。任何人都知道,美国推行“马歇尔计划”的目的是,使所有欧洲人确信,私有企业比共产主义企业更能给他们带来经济繁荣。在巴黎商谈“马歇尔计划”时,莫洛托夫的退席,以及苏联不让波兰和捷克斯洛伐克申请援助的结果是,欧洲的裂痕变得比以前更大。在美国数十亿美元的援助下(英国、法国、意大利和联邦德国等大国得到的援助最多),在北大西洋贸易体系内的西欧经济蒸蒸日上。在东欧,共产主义的控制则越来越严。1947年,共产党情报局成立。这是一个重新组建的、半公开的共产党国际组织。1948年,布拉格的多党政府被共产党发动的政变推翻。虽然铁托的南斯拉夫最终脱离了斯大林的严格控制,其他东欧国家却遭到清洗,并于1949年被迫加入“经济互助委员会”。该委员会不是苏联的“马歇尔计划”,而是“剥削其卫星国的一个新机构”。1946年丘吉尔就谈论“铁幕”也许有点为时过早,但两年之后,他的话便得到应验。

The intensification of East-West economic rivalries was complemented at the military level, and once again Germany was at the center of the dispute. In March 1947 the British and French had signed the Dunkirk Treaty, whereby each pledged all-out military support to the other signatory in the event of an attack by Germany (even though the Foreign Office in London held that contingency to be “rather academic” and was more concerned about western Europe’s internal weaknesses). In March 1948 this pact was extended, by the Brussels Treaty, to include the Benelux countries. The latter agreement did not mention Germany by name, but it is fair to say that many politicians in western Europe (especially France) were still obsessed with the “German problem” at this time rather than the “Russian problem. ”101 The antediluvian nature of their concerns was to be shaken up as 1948 unfolded. In the same month as the Brussels Treaty was signed, the Russians walked out of the Four- Power Control Council on Germany, claiming irreconcilable differences with the West over that country’s economic and political future. Three months later, in an effort to end the black market and currency chaos in Germany, the three western control powers announced the creation of a new deutsche mark. The Russian response to this unilateral action was not only to ban the West German notes from their zone but to clamp down on movements in and out of Berlin, that island of western influence one hundred miles into their sphere.

随着东西方经济对抗的加剧,其军事关系也变得日益紧张。在军事方面,德国又是争端的焦点。1947年3月,英国和法国签订了《敦刻尔克条约》。该条约规定,一旦遭到德国攻击,签约一方将向另一方全力提供军事援助(尽管当时英国外交部认为,发生那种突然情况的“可能性很小”,英国更关注西欧内部的弱点)。1948年3月,敦刻尔克条约被布鲁塞尔条约所取代,签约国除了英国、法国外,还有荷兰、比利时和卢森堡。虽然这后一个条约没有提到德国的名字,但可以说,当时西欧各国(特别是法国)的许多政治家们在感情上无法摆脱的是“德国问题”,而不是“苏联问题”。随着1948年的到来,他们这种传统的考虑问题的方法便受到冲击。在布鲁塞尔条约签订的那一个月,苏联人从四国德国管制委员会的会议上退席了,声称他们与西方人在德国的经济和政治前途问题上有无法调和的分歧。3个月之后,西方三国为了取缔德国的货币黑市交易和结束货币混乱状态,宣布发行新的德国马克。对此,苏联人做出的反应是,不仅禁止联邦德国货币在他们的管辖区内流通,还不许在柏林这个仅离西方势力范围100英里的“孤岛”上使用。

If anything brought the extent of the antagonism close to home, it was the Berlin crisis of 1948–1949. 102 Already officials in Washington and London were discussing means whereby a grouping of the European states, the dominions, and the United States could stand together in the event of hostilities with Russia. While—as with the Marshall Plan—the Americans wished the Europeans to come forward first with schemes for military security, there was by this stage no doubt as to how seriously the United States took the Communist challenge. A fullblown “Red scare” at home complemented tougher actions abroad. In March 1948, Truman was even asking Congress to reinstate conscription, a request granted in the Selective Service Act of June of that year. All of these moves were boosted by the Soviet blockade of the land routes to Berlin. While the age of air power enabled the Americans and British to call Stalin’s bluff by flying supplies into Berlin for the next eleven months, until the land access was restored, there had been many who argued for sending a military convoy to force its way to the city. It is difficult to believe that such an action would not have provoked a war; as it was, under a new treaty the United States moved a fleet of B-29 bombers to British airfields, a sign of their earnestness in the matter.

如果说有什么事件使西方人认识到东西方敌对立场的严重性,那就是1948~1949年的柏林危机。华盛顿和伦敦的官员们已在探讨,与苏联发生战争时如何使西欧各国、美国及其领地团结一致地采取行动。虽然美国人在执行“马歇尔计划”的同时,希望欧洲人首先拿出维护自身安全的军事计划,但毫无疑问,此时美国对共产主义的挑战已准备认真对待。美国国内患了严重的“恐赤病”,在国外则采取更加强硬的政策。1948年3月,杜鲁门要求国会恢复征兵制。当年6月,国会通过《选征兵役法》,满足了总统的要求。所有这些行动都是由于苏联封锁通往柏林的道路而尽快采取的。在以后的11个月中,即在通往柏林的陆路恢复使用之前,美国和英国为了顶住斯大林的压力,用飞机向西柏林运送了大量物资。尽管如此,仍有许多人建议派遣由军队护送的车队强行开往柏林。如果真的采取这一行动,就可能引发战争。根据一项新条约,美国将一个B-29轰炸机机群转到英国机场。这表明美国对柏林危机十分重视。

In these circumstances, even isolationist senators could be moved to support proposals for the creation of what was to be the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, with full American membership—and, indeed, with its chief strategical purpose being the provision of North American aid to the European states in the event of Russian aggression. In its early years, NATO reflected political concerns more than any exact military calculations, symbolizing as it did the historic shift in American diplomatic traditions as it took over from Britain as the leading western “flank” power, dedicated to maintaining the European equilibrium. In the view of the American and British governments, the chief task had been to tie the United States and Canada to the Brussels Pact signatories, and to extend the promise of mutual support to countries like Norway and Italy, which also felt insecure. On the day that the NATO treaty was signed, in fact, the U. S. Army had a mere 100,000 troops in Europe (compared with 3 million in 1945), and there existed only twelve divisions —seven French, two British, two American, one Belgian—in place to resist a Soviet push westward. Although the Russian forces at this period were nowhere near as large or capable as alarmist voices in the West claimed, the imbalance in each bloc’s troop totals was disquieting; slightly later, those fears were increased by the thought that the Communists could sweep over the northern German plain as swiftly as they had crossed the Yalu during the Korean War. This meant that while the NATO strategy increasingly relied upon the “massive retaliation” of American long-range bombers to answer a Soviet invasion, there was a commitment to build up large conventional armed forces as well. In turn, this had the effect of tying all three of the western “flank” Powers—the United States, Canada, and Britain—to permanent military obligations on the continent of Europe to a degree which would have amazed their respective strategic planners in the 1930s. 103

在这种情况下,即使是孤立主义思想严重的参议员也改变了立场,支持成立所谓的北大西洋公约组织的建议。西方建立以美国等国为正式成员国的北约(NATO)的主要战略目的是:当苏联发动侵略战争时,北美向欧洲各国提供支援。北约在成立后的最初几年里关心的主要是政治问题,而不是军事问题。这表现在美国作为西方一流“侧翼”强国,继承英国的衣钵后,奉行的外交政策发生了历史性变化,开始致力于维持欧洲的力量均势。在美国和英国政府看来,北约的主要作用是,可使美国和加拿大与《布鲁塞尔条约》的其他签约国联合起来,可将相互支持的保证扩大到挪威、意大利等也感到不安全的国家。在《北大西洋公约》签订之日,美国在欧洲实际上只有驻军10万人(在1945年则有300万),西方只部署了12个师(其中7个法国师、两个英国师、两个美国师和1个比利时师),用以阻止苏军西进。虽然这一时期苏军的兵力远不如蛊惑人心的西方人所宣传的那样大,但两大集团的总兵力对比是相差悬殊的。不久,西方人的恐惧更甚,认为共产党人可能像在朝鲜战争中很快渡过鸭绿江那样迅速占领北德平原。这就是说,北约在日益严重地依靠美国远程轰炸机实施“大规模报复”来对付苏军入侵的同时,还必须大力加强常规力量。另外,这还使三个西方“侧翼”大国(即美国、加拿大和英国)必须对欧洲大陆长期承担军事义务。对此,1930年代的西方战略制定者肯定会大吃一惊。

The NATO alliance did militarily what the Marshall plan had done economically; it deepened the 1945 division of Europe into two camps, with only traditional neutrals (Switzerland, Sweden), Franco’s Spain, and certain special cases (Finland, Austria, Yugoslavia) in neither one nor the other. It was to be answered, in due course, by the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact. This deepening division, in turn, made the prospects for a reunification of Germany ever more remote. Despite French worries, the West German armed forces began to be built up within the NATO structure by the late 1950s—which was logical enough, if the West really wanted to narrow the gap in troop totals. 104 But that inevitably moved the USSR to develop an East German army, albeit under special controls. With each German state integrated into its respective military alliance, it became inevitable that both blocs would regard any future German attempt to become neutral with alarm and suspicion, as a blow to their own security. In Russia’s case, this was reinforced, even after Stalin’s death in 1953, by the conviction that any country which had become Communist should not be permitted to abandon that creed (the “Brezhnev Doctrine,” to use later parlance). By October 1953, the U. S. National Security Council had privately accepted that the eastern European satellite states “could be freed only by general war or by the Russians themselves. ” As Bartlett cryptically notes, “Neither was possible. ”105 In 1953, too, a rising in East Germany was swiftly put down. In 1956, alarmed at the Hungarian decision to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, Russia moved its divisions back into that land and suppressed its independence. In 1961, in an admission of defeat, Khrushchev ordered the erection of the Berlin Wall to stem the flow of talent to the West. In 1968, the Czechs suffered the same fate as the Hungarians twelve years earlier, though the bloodshed was less. Each of these measures, taken by a Soviet leadership incapable (despite its official propaganda) of matching either the ideological or the economic appeal of the West, simply added to the division between the two blocs. 106

北约在军事上起的作用,与“马歇尔计划”在经济上的作用别无二致。它进一步加深了1945年分为两个阵营的欧洲的裂痕,使得只有瑞士和瑞典等传统中立国、佛朗哥的西班牙,以及处于特殊地位的芬兰、奥地利和南斯拉夫,处于两个集团之外。北约得到的回答是,以后不久以苏联为首的华约集团便成立了。这不仅加深了东西方的分裂,还使德国统一的前景变得更加渺茫。尽管法国人忧虑不安,联邦德国的武装部队到20世纪50年代末便在北约体制内开始建立起来。这是合乎逻辑的,因为西方希望缩小与华约在总兵力对比上的差距。但是,这也不可避免地会推动苏联建立一支民主德国军队,尽管这支军队要受严格控制。由于两个德国都加入了相应的军事联盟,对今后任何使德国中立的企图,北约和华约都必然会感到震惊和不安,会认为是对本身安全的打击。从苏联方面看,这种看法在斯大林1953年去世后反而得到了加强。这是因为苏联出现了这样一种观点:任何由共产党领导的国家都不能放弃自己的信条(就是后来人们所说的“勃列日涅夫主义”)。1953年10月,美国国家安全委员会成员曾私下承认,东欧卫星国“只能通过全面战争或苏联人得到解放”。而正如巴特利特所指出的,“这两种情况都不会发生”。1953年,民主德国的一次暴动很快被镇压下去。1956年,匈牙利决定退出华约,惊慌的苏联人立即派出几个师的军队,镇压了那里的独立运动。1961年,赫鲁晓夫下令建起柏林墙,以防止人才流向西方。1968年,捷克斯洛伐克人遭到了12年前匈牙利人一样的命运,尽管他们流的血要少一点。苏联领导人采取的这些行动只能进一步加深两大军事集团的分裂,却无法消除西方世界在思想和经济方面的吸引力。

The second main feature of the Cold War, its steady lateral escalation from Europe itself into the rest of the world, was hardly surprising. During much of the war itself, there had been an almost single-minded concentration of Russian energies upon dealing with the German threat; but that did not mean that Moscow had abandoned its political interest in the future of Turkey, Persia, and the Far East—as was made plain in August 1945. It was therefore highly unlikely that Russia’s quarrels with the West over European issues would be geographically limited to that continent, especially since the principles in dispute were of universal application—selfgovernment versus national security, economic liberalism versus socialist planning, and so on. More important still, the war itself had caused immense social and political turbulence, from the Balkans to the East Indies; and even in countries not directly overrun by invading armies (for example, India, or Egypt), the mobilization of manpower, resources, and ideas had led to profound changes. Traditional social orders lay smashed, colonial regimes had been discredited, underground nationalist parties had flourished, and resistance movements had grown up, committed not only to military victory but also to political transformation. 107 There was, in other words, an immense degree of political turbulence in the world situation of 1945, which could be a threat to Great Powers eager to restore peacetime stability as soon as possible; but this could also be an opportunity for each of the superpowers, imbued with their universalist doctrines, to bid for support among the vast swathe of peoples emerging from the debris of the collapsed older order. During the war itself, the Allies had given aid to all manner of resistance movements struggling against their German and Japanese overlords, and it was natural for those groups to hope for a continuation of such aid after 1945, even while they engaged in jostling with rival contenders for power. That some of these partisan groups were Communist and others bitterly anti-Communist made it more difficult than ever for decision-makers in Moscow and Washington to separate these regional quarrels from their own global preoccupations. Greece and Yugoslavia had already demonstrated how a local, internal dispute could swiftly be given an international significance.

“冷战”的第二个重要特点是,它从欧洲向世界其他地区逐渐进行横向扩散。这种情况的发生是不奇怪的。在第二次世界大战的很大一部分时间里,苏联人一心一意想的是如何对付德国人的威胁。但是,这并不是说,莫斯科对土耳其、波斯、远东各国的政治前途毫无兴趣(正如1945年8月所表明的那样)。因此,苏联与西方在欧洲问题上的争端在地理上不会只限于欧洲。这还因为,双方争论的原则具有普遍性,例如,是实行自治还是照顾国家安全,是实行自由经济还是社会主义计划经济,等等。更重要的是,第二次世界大战还使从巴尔干半岛到东印度群岛的广大地区发生了社会动荡和政治动乱。即使在没有直接受到德、意、日侵略军蹂躏的国家(如印度、埃及等国),由于进行了人力、物力和思想动员,也发生了深刻变化。传统的社会秩序被打乱,殖民政府威信扫地,地下的民族主义政党得到发展,抵抗运动的力量不断壮大。它们不仅专心致力于争取军事上的胜利,还要求进行政治改革。换句话说,1945年的世界形势充斥着政治动乱。这种动乱既可以对大国希望尽快恢复和平时期的稳定造成威胁,也可为掌握普遍适用的理论的每一个超级大国创造机遇,以争取从崩溃的旧秩序的废墟上站立起来的许多民族的支持。在第二次世界大战期间,同盟国对所有反对德国和日本统治的抵抗组织都提供援助。1945年战争结束后,这些组织继续要求得到援助也是很自然的,尽管它们都在忙于与敌对组织争权夺利。在这些组织中,一些是共产党领导的游击队,而另一些则与共产党不共戴天。这就使得莫斯科和华盛顿的决策者们更加难以区分地区性争端与全球性争夺。希腊和南斯拉夫发生的事件表明,地区性的国内争端可以迅速发展成具有国际意义的事件。

The first of the extra-European disputes between Russia and the West was very much a legacy of such ad hoc wartime arrangements; in 1941–1943 Iran had been placed under tripartite military protection, partly to ensure that it remained in the Allied camp, partly to ensure that none of the Allies gained undue economic influence with the Teheran regime. 108 When Moscow did not withdraw its garrison in early 1946, and instead seemed to be encouraging separatist, pro-Communist movements in the north, the traditional British objections to undue Russian influence in this part of the world were augmented, and then rather eclipsed, by the Truman administration’s strong protests. The withdrawal of the Russian troops, soon followed by the Iranian army’s suppression of the northern provinces and of the Tudeh (Communist) party itself, gave ample satisfaction in Washington, where it confirmed Truman’s belief in the efficacy of “talking tough” to the Soviets. The case demonstrated, in Ulam’s words, “the meaning of containment before the doctrine was actually enunciated,”109 and psychologically prepared Washington to react similarly against news of Russian activities elsewhere. Thus, the continuing civil war in Greece, Moscow’s pressure upon the Turks for concessions at the Straits and in the Kars border region, and the British government’s 1947 declaration that it could no longer maintain its guarantees to those two nations triggered off a public American response (in the “Truman Doctrine”) which was already in embryonic form. As early as April 1946 the State Department was urging the need to give support to “the United Kingdom and the communications of the British Commonwealth. ”110 The growing acceptance of such views, and the way in which Washington was beginning to link together the various crises along the “northern tier” of those countries which blocked Russian expansion into the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, indicates how swiftly the idealistic strands in American foreign policy were being joined, if not altogether replaced by geopolitical calculation.

苏联与西方之间发生在欧洲以外地区的第一次争端,源于战争期间同盟国达成的特别协议。1941~1943年,伊朗处于美、英、俄三国的共同军事保护之下。这一方面可以确保伊朗站在同盟国一边,另一方面可使美、英、俄三国任何一国都无法从德黑兰当局那里得到过多的经济利益。到1946年初,莫斯科不仅未从伊朗撤军,反而似乎对伊朗北部的分裂主义分子的活动予以支持。这更加深了本来就担心苏联人对伊朗施加过大影响的英国人的不满。不久,杜鲁门政府提出了强烈抗议。苏联军队撤离后,伊朗军队立即镇压了北方各省分裂主义分子的活动,并取缔了共产党。这不仅使华盛顿感到非常满意,而且还证实了杜鲁门确信的对苏联采取“强硬立场”的有效性。正如乌拉姆所指出的那样,伊朗事件“在遏制理论出台之前就证实了它的作用”,并使华盛顿做好了心理准备,对苏联在其他地区的行动也将如法炮制。因此,希腊内战的继续进行,莫斯科对土耳其施加压力让其在使用海峡和卡尔斯边界争端问题上做出让步,以及1947年英国政府宣布它已无力再对希、土两国承担义务,这一切便导致了美国公众的强烈反响(这是“杜鲁门主义”赖以产生的基础)。早在1946年4月,美国国务院就提出,必须支持“英国和英联邦的交通”。美国决策者逐渐接受了上述意见。并且,他们还开始把在可以阻止苏联向东地中海和中东扩张的那些国家(即“北部”)发生的各种危机联系起来考虑。这些情况表明,美国对外政策中的理想主义立场是如何迅速与地缘政治的考虑结合在一起的,如果不是完全为地缘政治的考虑所代替的话。

It was with this perception of the global advance of Communism that the western Powers also viewed the changes occurring in the Far East. In the case of the Dutch, who were soon to be ejected from their “East Indies” by Sukarno’s widely based nationalist movement, or the French, quickly embroiled in an armed struggle with Ho Chi Minh’s Vietminh, or the British, soon engaged in counterinsurgency warfare in Malaya, their response as old colonial powers might have been the same even had no Communist existed east of Suez. 111 (On the other hand, by the late 1940s it proved useful in gaining Washington’s sympathies, and in France’s case military aid also, to claim that the insurgents were master-minded by Moscow. ) But the shock to the United States of the “loss” of China was altogether more severe than these challenges farther south. From the time of American missionary endeavors in the nineteenth century onward, enormous amounts of cultural and psychological (much less financial) capital had been invested by the United States in that large and populous land; and this had been blown up to even greater proportions by the press coverage of Chiang Kai-shek’s government during the war itself. In more than the religious sense, the United States felt it had a “mission” in China. 112 And while the professionals in the State Department and the military were increasingly aware of the Kuomintang’s corruption and inefficiency, their perceptions were not generally shared by public opinion, especially on the Republican right, which by the late 1940s was beginning to see world politics in rigidly black-and-white terms.

西方国家在注视共产主义的全球性扩张的同时,也看到了远东正在发生的变化。荷兰人很快会被苏加诺领导的有广泛群众基础的民族主义运动组织从东印度群岛赶出去,法国人不久即被卷入了胡志明的越盟领导的武装斗争,英国人也不得不在马来亚进行反暴乱活动。即使在苏伊士运河以东没有共产党,这些老牌殖民大国也会采取同样的行动(另一方面,在20世纪40年代末之前,声称上述暴乱分子是由莫斯科操纵的,就可能得到华盛顿的同情和援助。法国也是得到军事援助的例子)。但是,在南亚发生的所有挑战,都不如“失去”中国对美国的震动大。从19世纪美国传教士进入中国以后,美国就向这个疆域辽阔、人口众多的国家,进行了大量文化、心理“投资”(财政投资较少)。而且,这些“投资”的规模由于在第二次世界大战时蒋介石政府报纸的宣传而夸大了许多倍。美国感到它在中国有一种超出宗教意义上的“天职”。即使国务院和军界的某些官员越来越清楚地看到国民党的腐败和无能,但是他们的观点却往往不能被公众舆论所接受,特别是不能被共和党右翼人士所接受。直至20世纪40年代末,共和党中右翼才开始用“非黑即白”的眼光看待世界政治。

The political turbulence and uncertainties which existed throughout the Orient in these years placed Washington in repeated dilemmas. On the one hand, the American republic could not be seen to be the supporter of corrupt Third World regimes or of decaying colonial empires. On the other, it did not want the “forces of revolution” to spread further, since that (it was claimed) would enhance Moscow’s influence. It was relatively easy to encourage the British to withdraw from India in 1947, for it simply involved a transfer to a parliamentary, democratic regime under Nehru. The same could be done in pressing the Dutch to leave Indonesia by 1949, although Washington still worried about the growth of Communist insurgency there —as it did in the Philippines (given independence in 1946). But elsewhere the “wobbling” was more in evidence. Instead of pushing ahead with the earlier notions of a full-blown social transformation and demilitarization of Japanese society, for example, Washington planners steadily moved toward ideas of rebuilding the Japanese economy through the giant firms (zaibatsu), and even toward encouraging the creation of Japan’s own armed forces—partly to ease the United States’ economic and military burdens, partly to ensure that Japan would be an anti- Communist bastion in Asia. 113

这些年在东方出现的政治动乱和动荡局势,多次使华盛顿陷入进退维谷的境地。一方面,我们不应把美国看成是第三世界国家腐败政权和腐朽的殖民帝国的维护者。另一方面,美国确实不希望“革命力量”发展壮大,因为那(据称)会扩大莫斯科的影响。1947年,要求英国人离开印度比较容易办到,因为这只涉及到将政权交给尼赫鲁领导的代议制的民主政府。同样,华盛顿也可敦促荷兰人1949年离开印度尼西亚,虽然它仍很担心共产主义的颠覆力量在那里不断壮大(美国对1946年独立的菲律宾也很不放心)。不过,在其他地区“变化”更大。例如,华盛顿的决策者本来计划在日本推行全面社会改革和非军事化政策,后来却逐渐改弦更张,决定发动美国的大企业重建日本经济,甚至鼓励日本组建军队,以减轻美国的经济、军事负担和确保日本成为亚洲的反共堡垒。

This hardening of Washington’s position by 1950 was the result of two factors. The first was the increasing attacks upon the more flexible “containment” policies of Truman and Acheson, not only by Republican critics and the fast-rising “red-baiter” Joe McCarthy, but also by newer diehards within the administration itself, such as Louis Johnson, John Foster Dulles, Dean Rusk, and Paul Nitze—compelling Truman to act more assertively in order to protect his domestic political flank. The second was the North Korean attack across the 38th parallel in June 1950, which was swiftly interpreted by the United States as but one part of an aggressive master plan orchestrated by Moscow. Together, these two factors gave the upper hand to those forces in Washington which desired a more active, and even belligerent, policy to stop the rot. “We are losing Asia fast,” wrote the influential journalist Stewart Alsop, invoking the homely imagery of a ten-pin bowling game. The Kremlin was the hardhitting, ambitious bowler.

1950年,美国采取强硬立场有两个原因。第一,杜鲁门和艾奇逊比较灵活的“遏制”政策,不仅受到了共和党人和引人注目的“红色诱饵”麦卡锡的越来越多的攻击,还受到了路易斯·约翰逊、约翰·杜勒斯、迪安·腊斯克和保罗·尼采等政府内新强硬分子与日俱增的批评。这迫使杜鲁门只得采取更坚决的行动,以确保国内政治侧翼的安全。第二,1950年6月朝鲜战争爆发,美国人迅速解释说,这是莫斯科制订的侵略总计划的一部分。由于这两个原因的综合作用,美国政府中主张对莫斯科采取强硬好战政策以制止接连失败的人占了上风。很有影响的记者斯图尔特·艾尔索普说,“我们将很快失去亚洲”,并拿10个木瓶的保龄球游戏作比喻,认为野心勃勃、拼命掷球的投球者是莫斯科。他写道:

The head pin was China. It is down already. The two pins in the second row are Burma and Indochina. If they go, the three pins in the next row, Siam, Malaya, and Indonesia, are pretty sure to topple in their turn. And if all the rest of Asia goes, the resulting psychological, political and economic magnetism will almost certainly drag down the four pins of the fourth row, India, Pakistan, Japan and the Philippines. 114

第一个木瓶是中国。第二排中的两个木瓶是缅甸和越南。如果它们倒了,第三排中的三个木瓶泰国、马来亚和印度尼西亚肯定也会倒下。这些国家倒下后所造成的心理、政治和经济影响,又肯定会将第四排中的印度、巴基斯坦、日本和菲律宾推倒。

The consequences of this change of mind affected American policy throughout East Asia. Its most obvious manifestation was the rapidly escalating military support to South Korea—an unsavory and repressive regime, which must share the blame for the conflict, but was at this time seen as an innocent victim. The early U. S. air and naval support was soon reinforced by army and marine divisions, which permitted MacArthur to launch his impressive counterattack (Inchon) until the northward advance of the United Nations forces in turn provoked China’s own intervention in October/November 1950. Denied the use of A-bombs, the Americans were forced to conduct a campaign reminiscent of the trench warfare of 1914– 1918. 115 By the time the cease-fire was reached, in June 1953, the United States had spent about $50 billion to fight the war, had sent over 2 million servicemen to the war zone, and had lost over 54,000 of them. While it had contained the North, the United States had also created for itself a long-lasting and substantial military commitment to the South from which it would be difficult, if not impossible, to withdraw.

美国人这种心理上的变化,对美国的东亚政策影响很大。其中最明显的表现是,对南朝鲜军事支援的逐步升级。南朝鲜政府声名狼藉,镇压人民,对朝鲜战争的发端必须分担责任,当时却被华盛顿看成了无辜的受害者。美国首先派出海、空军进行支援,接着又派遣陆军和海军陆战师增援。这使麦克阿瑟得以实施大规模的仁川反攻战役,并使联合国军队不断向北推进,反过来激起中国于1950年10~11月出兵援朝。由于不能使用原子弹,美国人只得实施1914~1918年堑壕战的作战方式。到1953年6月停战协定签订时,美国在战争中已耗资500亿美元,先后向战区派出200万以上的部队,牺牲官兵5.4万。虽然北朝鲜的进攻被制止了,但美国又对南朝鲜承担了长期的重要的军事义务,使它很难摆脱,如果不是不能摆脱的话。

This fighting also led to significant changes in American policy elsewhere in Asia. By 1949, many in the Truman administration had given up support of Chiang Kaishek in disgust, viewed the “rump” government in Taiwan with contempt, and were thinking of following the British in recognizing Mao’s Communist regime. Within another year, however, Taiwan was being supported and protected by the U. S. fleet, and China itself was regarded as a bitter foe, against which (at least in MacArthur’s view) it would be necessary to use atomic weapons to counter its aggressions. In Indonesia, so important for its raw materials and food supplies, the new government would be given aid to fight the Communist insurgents; in Malaya, the British would be encouraged to do the same; and in Indochina, while still pressing the French to establish a more representative form of government, the United States was now prepared to pour in arms and money to combat the Vietminh. 116 No longer convinced that the moral and cultural appeal of American civilization was enough to prevent the spread of communism, the United States turned increasingly to military-territorial guarantees, especially after Dulles became secretary of state. 117 Even by August 1951 a treaty had reaffirmed U. S. air- and naval-base rights to the Philippines and American commitments to the defense of those islands. A few days later, Washington signed its tripartite security treaty with Australia and New Zealand. One week later, the peace treaty with Japan was finally concluded, legally ending the Pacific war and restoring full sovereignty to the Japanese state—but on the same day a security pact was signed, keeping American forces both in the home islands and in Okinawa. Washington’s policy toward Communist China remained unrelentingly hostile, and toward Taiwan increasingly supportive, even over such minor outposts as Quemoy and Matsu.

这场战争还致使美国对亚洲其他地区的政策发生了巨大变化。1949年,杜鲁门政府的许多官员,由于讨厌国民党的所作所为,已不再支持蒋介石,蔑视逃到中国台湾的“残余政府”,并考虑效法英国,承认毛泽东的共产党政权。然而,时隔一年之后,中国台湾却又得到支持及美国海军舰队的保护,中国被视为不共戴天之敌,为制止中国“侵略”甚至可考虑使用核武器(至少,这是麦克阿瑟的观点)。印度尼西亚以物产丰富而著称,美国对其新政府提供援助的目的是,让其与共产党领导的革命者作斗争。对马来亚,美国则要求英国提供援助。在印度支那,美国在敦促法国人建立一个更有代表性的政府的同时,还准备送去大量武器和美元,帮助法国人同越盟作战。事实证明,只凭美国文明中精神和文化方面的吸引力,已不足以防止共产主义的传播。因此,美国便越来越多地求助于军事条约,杜勒斯就任国务卿后更是如此。1951年8月,美国与菲律宾签订条约。这不仅再次肯定了美国使用在菲律宾的海、空军基地的权利,还使美国承担了保卫菲律宾群岛的义务。几天之后,华盛顿与澳大利亚和新西兰签订三国安全协定。一周过后,美国与日本的和平条约最后缔结,从而在法律上结束了太平洋战争,并将国家主权交还日本。与此同时,美日之间还签订了安全条约,使美军得到了常驻日本本土诸岛和冲绳岛的权利。华盛顿对共产党领导的中国仍然采取非常敌视的政策,对中国台湾当局提供的援助越来越多,甚至支持蒋介石坚守金门、马祖等前沿据点。

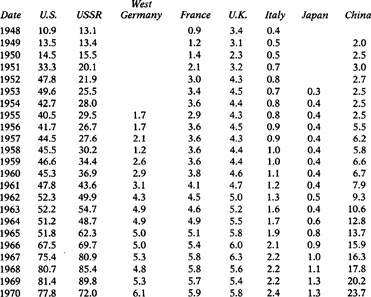

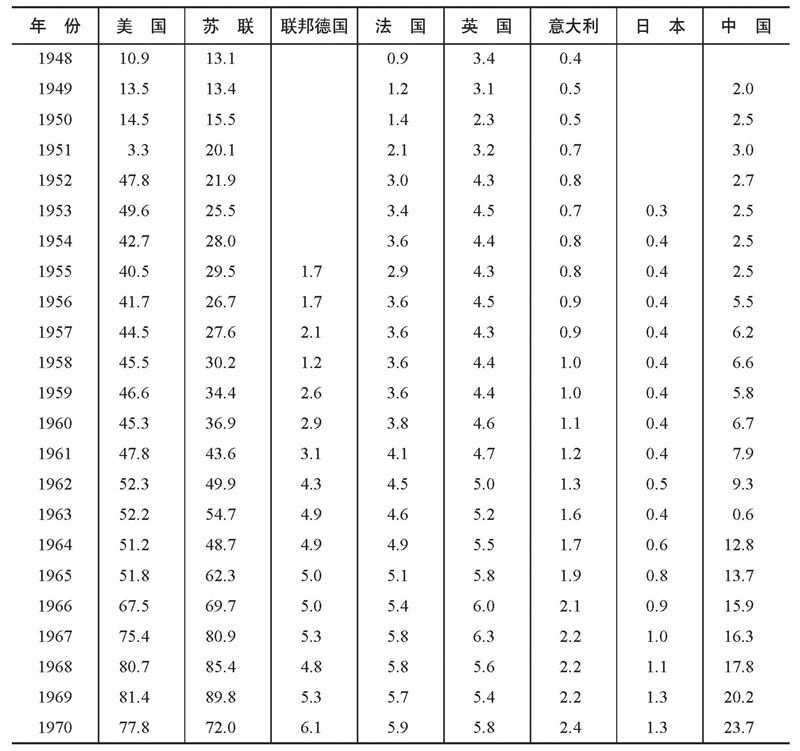

The third major element in the Cold War was the increasing arms race between the two blocs, along with the creation of supportive military alliances. In terms of monies spent, the trend was by no means an even one, as shown in Table 37.

“冷战”的第三个主要因素是,以美苏为首的两大集团之间的军备竞赛愈演愈烈,并分别成立了许多军事联盟组织。如表37所示,各国的军费开支是不平衡的。

Table 37. Defense Expenditures of the Powers, 1948-1970118

表37 1948~1970年各大国国防开支

(billions of dollars)

(单位:10亿美元)

The enormous surge in American defense expenditures for several years after 1950 clearly reflected the costs of the Korean War, and Washington’s belief that it needed to rearm in a threatening world; the post-1953 decline was Eisenhower’s attempt to control the “military-industrial complex” before it damaged both society and economy; the 1961–1962 increases reflected the Berlin Wall and Cuban missile crises; and the post-1965 jump in spending showed the increasing American commitment in Southeast Asia. 119 Although the Soviet figures are mere estimates and Moscow’s policy was shrouded in mystery, it is probably fair to deduce that its own 1950–1955 buildup was caused by worries that war with the West would lead to devastating aerial attacks upon the Russian homeland unless its numbers of aircraft and missiles were greatly augmented; the 1955–1957 reductions reflect Khrushchev’s détente diplomacy and efforts to release funds for consumer goods; and the very strong buildup after 1959–1960 reveals the worsening relations with the West, the humiliation over the Cuba crisis, and the determination to be strong in all services. 120 Communist China’s more modest buildup was as much a reflection of its own economic growth as of anything else, but the 1960s defense increases suggest that Peking was willing to pay the price for its break with Moscow. As for the western European states, the figures in Table 37 show both Britain and France greatly increasing their defense expenditures at the time of the Korean War, and France’s expenditures still rising until 1954 because of its embroilment in Indochina; but thereafter both those powers, and West Germany, Italy, and Japan in their turn, permitted only modest increases (and an occasional decline) in defense spending. Apart from China’s growth—and those figures also are very imprecise—the pattern of arms spending in the 1950s and 1960s still conveys the impression of a bipolar world.

1950年之后的几年中,美国国防开支的急剧增加反映了朝鲜战争的花费,以及华盛顿认为在一个危险的世界里必须重整军备的观点。1953年后,国防开支的减少,反映了艾森豪威尔政府试图制约“军事工业系统”,以防止它对社会与经济造成危害。1961~1962年军费的增长,是由于发生了柏林墙危机和古巴导弹危机。1965年后军费又有大幅度增加,则说明美国在东南亚战争中愈陷愈深。苏联历年军费数额是估算出来的,因为莫斯科的政策神秘莫测。尽管如此,我们的下述推论可能是正确的:苏联1950~1955年增加军费,是由于担心与西方发生战争后,苏联本土将遭到可造成巨大破坏的空中攻击,因而必须大量生产飞机和导弹;1955~1957年军费逐渐减少,说明赫鲁晓夫在执行“缓和”的外交政策,并企图将更多的费用用于生产消费品;1959~1960年后国防开支的急剧增加,是由于与西方的关系不断恶化,在古巴危机事件中受辱,以及莫斯科决心加强各军兵种的力量。社会主义中国的军事开支增长幅度较小,这既反映了它的经济发展,也有其他因素。但是,20世纪60年代军费的增加表明,中国决心为同莫斯科决裂付出代价。如表37所示,在朝鲜战争期间,英国和法国的国防开支都有很大增加,而法国由于陷入印度支那战争,其军费到1954年一直在增加。但自此以后,上述两国,以及联邦德国、意大利和日本,在军费的增加幅度上便减小了,有时还有所下降。除了中国的国防开支(这些数字很不准确)逐年增加外,20世纪50和60年代其他大国的军费变化情况,反映了两极世界的特征。

Perhaps more significant than figures alone was the multilevel and multisided character of the arms race. Although shocked by the Russian achievement of manufacturing its own A-bomb in 1949, the United States believed that it could inflict far more damage upon the USSR in a nuclear exchange than the USSR could inflict on it. On the other hand, as the strongly ideological NSC-68 (National Security Council Memorandum 68, of January 1950) put it, it was imperative “to increase as rapidly as possible our general air, ground and sea strength and that of our allies to a point where we are militarily not so heavily dependent on atomic weapons. ”121 Between 1950 and 1953, in fact, U. S. ground forces tripled in size, and although much of this was due to the calling-up of reserves to fight in Korea, there was also a determination to convert NATO from a set of general military obligations into an on-the-ground alliance—to forestall a Soviet overrunning of western Europe which both American and British planners feared likely at this time. 122 Although there was no real prospect of the fantastic total of ninety Allied divisions being created on the lines of the Lisbon Agreement of 1952, there was nonetheless a significant rise in military commitments to Europe—from one to five U. S. divisions by 1953, with Britain agreeing to station four divisions in Germany, so that a reasonable balance had been achieved by the mid-1950s, when the West German army was expanded to compensate for reductions made then by London and Paris. In addition, there were enormous increases in Allied expenditures upon their air forces, so that some 5,200 were available to NATO by 1953. While much less is known about the development of the Soviet army and air force in these years, it is clear that Zhukov was engaged upon significant reorganization once Stalin died— getting rid of masses of half-prepared troops, making units much more powerful, mobile, and compact, replacing artillery with missiles, and, in sum, giving them a much better capacity for offensive action than they had possessed in 1950–1951, when the West’s fear of attack was greatest. At the same time, it is clear that Russia, too, was placing the greatest proportion of these budgetary increases upon defensive and offensive air power. 123

比军费数字本身更为重要的,是多层次和多边的军备竞赛。1949年,苏联已能生产原子弹,这使美国大为震惊。尽管如此,美国仍认为,在核交战中美国对苏联造成的破坏要比苏联对它造成的破坏大得多。另一方面,意识形态性很强的NSC-68(即1950年1月的国家安全委员会第68号备忘录)则要求,美国必须“以尽可能快的速度普遍加强自己和盟国的空军、陆军和海军力量,以减少在军事上对原子武器的依赖”。从1950年至1953年,美军地面部队的兵力实际上增加了三倍,虽然这主要是由于美国动员了预备役部队到朝鲜打仗。此外,美国还决心要把北约从一个承担一般军事义务的伙伴改变成一个地面作战部队的联盟,以便阻止当时英美战略计划制订者担心很可能发生的苏军占领西欧。根据1952年缔结的《里斯本条约》,北约各国应部署90个师。虽然达到这个数字不切实际,但各国对欧洲承担的军事义务显著增多。例如,到1953年,驻欧美军已由1个师增至5个师;英国也同意在德国部署4个师。鉴于英法两国撤走了部分军队,联邦德国军队进行了扩编。因此,至1950年代中期,北约与华约的军力对比已大体平衡。另外,北约各国还为加强空军而大幅度增加了军费开支;到1953年.北约已有飞机5200架。在这几年中,苏联陆军和空军的发展情况鲜为人知。不过,有一点很清楚,那就是斯大林死后,朱可夫在军事上进行了重大改革:遣散了大量非正规部队,使正规部队的结构变得更合理、战斗力更强、机动力更快,以导弹取代了炮兵,等等。总而言之,与西方最担心遭到进攻的1950~1951年相比,苏军的进攻作战能力有了很大加强。还有一点人们也很清楚,在此期间苏联将其增加的很大一部分军事预算用于加强进攻性和防御性空中力量。

A second and quite new area of the East-West arms race opened up at sea, although this was also in an irregular pattern. The U. S. Navy had finished the Pacific war trailing clouds of glory, because of the impressive performance of its fast-carrier task forces and its submarine fleet; and the Royal Navy also felt that it had had a “good war,” and one much more decisively fought than the stalemated 1914–1918 conflict at sea. 124 But the coming of A-bombs (especially in the Bikini trials against a variety of warships) to be carried by long-range strategic bombers or missiles seemed to cast a cloud over the future of the traditional instruments of naval warfare and even over the aircraft carrier itself. In the post-1945 retrenchment of defense expenditures, and “rationalization” of the separate services into a unified defense ministry, both navies came under heavy pressure. They were rescued, at least to some extent, by the Korean War, which again saw amphibious landings, carrier-based air strikes, and the clever exploitation of western sea power. The U. S. Navy was also able to join the nuclear club with the creation of a new class of enormous carriers, possessing strike bombers equipped with atomic weapons, and, by the late 1950s, with the planned construction of nuclear-powered submarines capable of firing long-range ballistic missiles. The British, less able to afford modern carriers, nonetheless retained converted “commando” carriers for what were termed brushfire wars, and, like the French, also strove to create a submarine-based deterrent. If all western navies by 1965 contained fewer ships and men than in 1945, they certainly had a more powerful punch. 125

东西方军备竞赛的第二个领域是海军。这一新领域的竞赛情况比较混乱。刚刚结束太平洋战争的美国海军,因其快速航母特混编队和潜艇部队在战争中表现出色,仍然沉浸在胜利的荣耀之中。英国皇家海军也感到,它打了一场“真正的战争”。与1914~1918年那场双方相持不下的战争相比,这场战争打得痛快得多。但是,由于远程战略轰炸机或导弹携载的原子弹的问世(尤其是在比基尼岛进行了攻击战舰的试验之后),使人们对进行海战的传统手段甚至航空母舰的前途产生了怀疑。1945年后,美英海军都陷入困境。因为两国军费拮据,并将各独立军种置于一个统一的国防部之内。然而,这两支海军至少在一定程度上由于朝鲜战争的爆发而得救。在朝鲜战争中,人们又看到了两栖登陆作战、舰载航空兵空中突击和西方国家机敏地使用海上力量。不久,美国海军也加入了“核俱乐部”。这是因为,载有携带原子武器的突击轰炸机的巨大的新式航母建造成功,以及到20世纪50年代末美国计划建造能发射远程弹道导弹的核动力潜艇。没钱建造现代化航空母舰的英国人,却保留了经过改装的“突击”航母,用于对付小规模局部战争,并像法国人一样,也在为建立一支以潜艇为基础的威慑力量而努力。虽然西方各国海军20世纪65年拥有的舰艇和人员少于1945年,但它们的作战能力却已今非昔比。

But the greatest stimulus to the continued expenditure of these navies was the buildup of the Soviet fleet. During the Second World War itself, the Russian navy had achieved very little, despite its large submarine force, and most of its personnel had fought on land (or assisted at river crossings by the army). After 1945, Stalin permitted the construction of many more submarines, based upon superior German designs and probably to be employed in an extended coastal-defense role; but he also favored the creation of a larger surface navy, including battleships and aircraft carriers. This ambitious scheme was swiftly halted by Khrushchev, who saw no purpose in building large, expensive warships in an age of nuclear missiles; in this his views were identical to those of many politicians and air marshals in the West. What probably shook that assumption was the repeated examples of the use of surface sea power by Russia’s most likely foes—the Anglo-French sea-based attack upon Suez in 1956, the landing of U. S. forces in Lebanon in 1958 (thus checking the Russian-backed Syrians), and especially the cordon sanitaire which American warships placed around Cuba in the tense confrontation of the missile crisis of 1962. The lesson which the Kremlin (urged on by the influential Admiral Gorschkov) drew from these incidents was that until Russia also possessed a powerful navy, it would continue to be at a serious disadvantage in the world-power stakes—a conclusion reinforced by the U. S. Navy’s rapid move to Polaris-missile-carrying submarines in the early 1960s. The result was both a massive expansion in virtually all classes of vessels in the Red Navy—cruisers, destroyers, submarines of all types, hybrid aircraft-carriers—and a massive expansion in their deployment overseas, challenging western maritime predominance in, say, the Mediterranean or the Indian Ocean in a manner which Stalin had never attempted. 126

然而,促使西方各国海军开支不断增加的最大动力,是苏联海军的日益强大。在第二次世界大战中,苏联海军建树甚微(尽管它有一支规模可观的潜艇部队),海军军人也大部分在陆上作战,或帮助陆军部队强渡江河。1945年以后,斯大林下令根据德国性能优良的潜艇设计图纸,建造更多的潜艇,用于保卫广大的沿海水域。同时,他还主张建设一支包括战列舰和航空母舰在内的庞大的水面舰艇舰队。这一宏大的计划的实施,由于赫鲁晓夫的上台而很快停止了。这位苏联新领导人认为,在导弹核武器时代建造耗费巨资的大型军舰毫无意义。在这一方面,他的观点与西方许多政治家和空军元帅的观点并无二致。使苏联领导人对自己的看法产生怀疑的原因可能是,他们的敌国多次使用了水面舰艇部队,如1956年英法联军依托海军舰艇攻击了苏伊士地区,1958年美军在黎巴嫩登陆(从而阻止了苏联支持的叙利亚军队的扩张),在1962年的导弹危机中,美国军舰在古巴周围水域建立了警戒线。克里姆林宫(在有影响的海军司令戈尔什科夫的敦促下)从这些事件中得出的结论是,苏联如果没有一支强大的海军,在世界大国的争夺中将永远处于不利地位。由于美国海军20世纪60年代初开始装备“北极星”导弹潜艇,苏联人更深信这一结论的正确性。结果是,苏联海军中的各类舰艇(如巡洋舰、驱逐舰、各式潜艇、航空母舰等)数量大增,苏联在远洋海域部署的舰船迅速增加。这以斯大林未曾想过的方式向西方各国在地中海、印度洋等水域的海军优势提出了挑战。

This form of challenge could, however, be regarded in traditional terms, as was clear by the many comparisons which observers made between Admiral Gorschkov’s buildup and Tirpitz’s four decades earlier; and even if the Soviet Union appeared committed to a new “naval race,” it would be decades (if at all) before it could match the massively expensive carrier task forces of the U. S. Navy. The really revolutionary aspect of the post-1945 arms race was occurring elsewhere, in the sphere of atomic weapons and long-range missiles to project them. Despite the horrific casualties caused at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there still remained many who saw in atomic weapons “just another bomb” rather than a watershed in the history of man’s capacity for destruction. Moreover, following the failure of the 1946 Baruch Plan to internationalize atomic-power developments, there was the comforting thought that the United States possessed a nuclear monopoly and that the Strategic Air Command’s bombers compensated for (and deterred) the large Soviet superiority in ground forces;127 the western European states in particular accepted that a Russian military invasion would be answered by American (and later British) airborne bombings with nuclear weapons.

各国观察家把戈尔什科夫时期苏联海军力量的增长,与40年前蒂尔皮茨时期德国海军力量的增长做过多次比较。这些比较清楚地说明了这种挑战的性质。即使苏联决心与西方进行新的“海军军备竞赛”,它的海军舰队在实力上要赶上美国海军耗费巨资建立起来的航母舰队,也要数十年的时间。1945年后,军备竞赛中真正起到革命性影响的方面发生在其他领域,如原子武器及远程导弹的设计领域。尽管原子弹在广岛和长崎造成了极其可怕的伤亡,但仍有人认为原子弹只是“另一种炸弹”,而不把它看成是人类杀伤能力历史上的一个分水岭。而且,1946年巴鲁克倡导原子武器研制国际化失败之后,西方出现了一种可使人高枕无忧的思潮,认为美国垄断了核武器,“战略空军司令部”的轰炸机可抵消苏军在地面部队方面的巨大优势。西欧各国还认为,对苏联军事入侵的回答将是,美国(以后还有英国)的载有核武器的飞机的轰炸。

Technological innovations, and Soviet advances especially, changed all that. Russia’s successful explosion of an atomic device in 1949 (well before most western estimates had predicted) broke the American monopoly. More alarming still was the construction of long-range Russian bombers, especially of the Bison type, which by the mid-1950s not only were assumed to be capable of reaching the United States but also were (erroneously) supposed to exist in such large numbers that a “bomber gap” existed. While the resultant controversy signified both the difficulty of gaining hard evidence about Russian capabilities and the U. S. Air Force’s tendency to exaggerate,128 it was in fact only to be a few more years before the era of American invulnerability was over. In 1949 Washington had agreed to the production of a new “super” bomb (the H-bomb), of staggeringly larger destructive capacity. This seemed once again to promise to the United States a decisive advantage, and the early to middle 1950s witnessed, both in Foster Dulles’s startling speeches and in the Air Force’s own plans, a commitment to “massive retaliation” upon Russia or China in the event of the next war. 129 While this doctrine itself produced considerable private unease within both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations—leading to the buildup of conventional forces and tactical (i. e. , “battlefield”) nuclear weapons, as alternatives to unleashing Armageddon—the chief blow to that strategy came from the Russian side. In 1953, Russia also tested an Hbomb, a mere nine months after the American test. Moreover, the Soviet government had devoted considerable resources to exploiting German wartime technology on rocketry. By 1955 the USSR was mass-producing a medium-range ballistic missile (the SS-3); by 1957 it had fired an intercontinental ballistic missile over a range of five thousand miles, using the same rocket engine which shot Sputnik, the earth’s first artificial satellite, into orbit in October of the same year.

技术革命,特别是苏联的技术进步,改变了一切。1949年苏联原子装置爆炸成功(这比大多数西方人预计的要早得多),打破了美国的核垄断。更令人惊异的是,20世纪50年代中期苏联就生产出远程轰炸机(如“野牛”式轰炸机)。美国人不仅认为这些飞机能飞抵美国,还揣测(这是错误的)这些飞机的数量已超过美国。关于苏联轰炸机数量的争论表明,得到苏军作战能力的确切情报相当困难,美国空军经常夸大苏联空军的力量。尽管如此,又过了几年,美国可免受攻击的时代就结束了。1949年,美国政府决定生产一种新的“超级”炸弹(即氢弹)。这种炸弹的杀伤能力大得令人吃惊。氢弹的问世似乎再次使美国处于绝对优势地位。从20世纪50年代初期到中期,这一点在杜勒斯气势汹汹的报告和空军的作战计划中都有体现。在这一时期,美国计划一旦下一次战争爆发,就对苏联或中国实施“大规模报复”。在杜鲁门和艾森豪威尔政府中,很多人私下对“大规模报复”战略可能导致的后果表示不安。因此,他们要求加强常规兵力和研制战术(即“战场”)核武器,以避免进行无限制地使用战略核武器的“大决战”。但是,对大规模报复战略的主要打击则来自苏联。1953年,即在美国之后9个月,苏联也进行了氢弹试验。而且,苏联政府还将大量财力物力用于发展德国战时开发的火箭技术。到1955年,苏联已批量生产中程弹道导弹(SS-3)。1957年,苏联又发射了一枚洲际弹道导弹,射程达5000英里,所用的火箭发动机在同年10月又将世界第一颗人造地球卫星送上了轨道。

Shocked by these Russian advances, and by the implication that both U. S. cities and U. S. bomber forces might be vulnerable to a sudden Soviet strike, Washington committed massive resources to its own intercontinental ballistic missiles in order to close what was predictably termed “the missile gap. ”130 But the nuclear arms race was not confined to such systems. From 1960 onward, each side was also swiftly developing the capacity to launch ballistic missiles from submarines; and by that time a whole variety of battlefield nuclear weapons, and shorter-range rockets, had been constructed. All this was attended by the intellectual wrestlings of both strategic planners and civilian analysts in their “think tanks” about how to manage the various stages of escalation in what was now a strategy of “flexible response. ” However clear the solutions proposed, none of this managed to escape from the awful problem that it was going to be difficult if not impossible to integrate nuclear weapons into the traditional ways of fighting conventional warfare (it was soon realized, for example, that the battlefield “nukes” would blow up most of Germany). Yet if recourse were had to launching high-yield H-bombs upon Russian and American soil, the mutual casualties and damage would be unprecedented. Locked in what Churchill called a mutual balance of terror, and unable to dis invent their weapons of mass destruction, Washington and Moscow threw more and more resources into the technology of nuclear warfare. 131 And while both Britain and France were pushing ahead with their own atomic bombs and delivery systems in the 1950s, it still seemed—by all contemporary measure of aircraft, missiles, and nuclear bombs themselves—that in this field, too, only the superpowers counted.

苏联人在军事上取得的这些进步使美国人受到很大震动。这就是说,美国的城市和轰炸机部队都可能遭到苏联的突然袭击。于是,华盛顿投入大量资源,发展洲际弹道导弹,以便缩短与苏联的所谓“导弹差距”。但是,核军备竞赛并不仅限于这些方面。1960年以后,美苏不仅大力发展从潜艇发射弹道导弹的技术,还生产了多种战术核武器和近程火箭弹。与此同时,美国“思想库”的战略制定者和文职分析家们,还在绞尽脑汁地制订根据“灵活反应”战略的要求,对战争升级过程中每一阶段进行控制的计划。不管制订出的计划多么周密,它们都必须涉及如何将核武器纳入打常规战争的传统战法这个极难解决的问题(例如,美国战略家意识到,战场核武器会很快将大半个德国化为焦土)。如果美苏双方都向对方的国土投掷大当量氢弹,那么相互造成的伤亡和破坏将是空前的。由于陷入丘吉尔所说的“相互的恐怖平衡”之中,由于无法再回到这种大规模杀伤武器没发明之前的世界,华盛顿和莫斯科便把越来越多的资源用于发展核技术,准备核战争。虽然英法两国20世纪50年代也在大力发展原子武器及其发射系统,但从拥有的飞机、导弹和核武器本身来看,只有两个超级大国可称得上核国家。

The final major element in this rivalry was the creation by both Russia and the West of alliances across the globe, and the competition to find new partners—or at least to prevent Third World countries from joining the other side. In the early years, this was overwhelmingly an American activity, flowing from its advantageous position in 1945, from the fact that it already had many garrisons and air bases outside the western hemisphere, and from the equally important fact that so many countries were looking to Washington for economic and sometimes military support. By contrast, the USSR was desperately needing to rebuild itself, its chief foreign concern was the stabilization of its own borders on terms favorable to Moscow, and it had neither the economic nor the military instruments of power to project itself farther afield. Despite territorial gains in the Baltic, northern Finland, and the Far East, Russia was still, relatively speaking, a landlocked superpower. Moreover, it now seems clear that Stalin’s view of the world outside was one overwhelmingly charged with caution and suspicion—toward the West, which, he feared, would not tolerate open Communist gains (e. g. , in Greece in 1947); and also toward those Communist leaders, such as Tito and Mao, who were certainly not “Soviet puppets. ”132 The setting-up of the Cominform in 1947 and the strong propaganda about supporting revolutionaries abroad had echoes from the 1930s (and even more, from the 1918–1921 era); but in actual fact Moscow seems to have avoided foreign entanglements in this period.

这场争斗中的最后一项重要内容是,苏联和西方在全球范围内竞相成立军事联盟,竞相寻求新伙伴,或至少阻止第三世界国家站到对方一边。在二次大战后的最初几年里,处于有利地位的美国进行了大量结盟活动。当时的情况是:美国在西半球之外已有许多空军基地,并在许多国家驻有军队;许多国家希望华盛顿向它们提供经济和军事援助。相比之下,苏联则处于不利地位,它的当务之急是重建家园,它的外交政策的主要目标是使边界的确定对自己有利,它没有足够的经济和军事力量去把战场拉远。尽管在波罗的海地区、芬兰北部和远东苏联领土有所扩张,但它基本上仍是一个大陆性超级大国。另外,现在看来有一点很清楚,斯大林对外部世界、对西方疑虑甚深,且奉行谨慎的政策。他担心,西方不允许苏联公开进行共产主义扩张(如1947年的希腊)。同时,斯大林对不愿当“苏联傀儡”的铁托、毛泽东等共产党领导人也很不放心。1947年,苏联共产党情报局成立。而且,苏联仿效20世纪30年代(甚至1918~1921年)的做法,大肆宣传支持世界革命。但实际上,苏联在这一时期采取的政策是尽量避免卷入国外纠纷。

Yet the view from Washington, as noted above, was that a master plan for world Communist domination was unfolding, step by step, and needed to be “contained. ” The proffered guarantees to Greece and Turkey in 1947 were the first sign of this change of course, and the 1949 NATO treaty was its most spectacular exemplar. With the further additions to NATO’s membership in the 1950s, this meant that the United States was pledged “to the defense of most of Europe and even parts of the Near East—from Spitzbergen to the Berlin Wall and beyond to the Asian borders of Turkey. ”133 But that was only the beginning of the American overstretch. The Rio Pact and the special arrangement with Canada meant that it was responsible for the defense of the entire western hemisphere. The ANZUS treaty created obligations in the southwestern Pacific. The confrontations in East Asia during the early 1950s had led to the signing of various bilateral treaties, whereby the United States was pledged to aid countries along the “rim”—Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, as well as the Philippines. In 1954, this was buttressed further by the establishment of SEATO (the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization), whereby the United States joined Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Thailand in promising mutual support to combat aggression in that vast region. In the Middle East, it was the chief sponsor of another regional grouping, the 1955 Baghdad Pact (later, the Central Treaty Organization, or CENTO), in which Britain, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan stood against subversion and attack. Elsewhere in the Middle East, the United States had evolved or was soon to evolve special agreements with Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan, either because of the strong Jewish-American ties or in consequence of the 1957 “Eisenhower Doctrine,” which proffered American aid to Arab states. Early in 1970, one observer noted, the United States had more than 1,000,000 soldiers in 30 countries, was a member of four regional defense alliances and an active participant in a fifth, had mutual defense treaties with 42 nations, was a member of 53 international organizations, and was furnishing military or economic aid to nearly 100 nations across the face of the globe. 134

然而,如上所述,华盛顿却认为,苏联在一步一步地推行一项以共产主义统治世界的总体计划,必须加以“遏制”。1947年,美国对希腊和土耳其做出承诺,是华盛顿的政策发生变化的第一个征兆;1949年北约的成立,则是美国政策发生变化最明显的标志。进入20世纪50年代后,北约成员国增多。这表明美国决心保卫欧洲大部和中东一部,即从斯瓦尔巴群岛到柏林墙到土耳其在亚洲的边界。不过,这只是美国承担过多国际义务的开始。《里约热内卢条约》[3]和与加拿大的特别协定的签订,意味着美国要负责保卫整个西半球。美、澳、新条约的缔结,则使美国又对西南太平洋的安全承担了义务。20世纪50年代初期在东亚发生的军事对抗,导致美国签订了许多双边协定,使华盛顿做出了援助日本、南朝鲜、中国台湾和菲律宾的保证。1954年,东南亚条约组织成立,从而使美国将英国、法国、澳大利亚、新西兰、菲律宾、巴基斯坦、泰国聚集在一起,相互支援,共同对付在这一广大地区发生的侵略战争。在中东,美国倡议成立了另一个地区性集团——巴格达条约组织(后来称为中央条约组织),这使英国、土耳其、伊拉克、伊朗和巴基斯坦共同对付颠覆侵略有了组织保证。在中东的其他地区,美国与以色列、沙特阿拉伯、约旦则缔结了特别协定。这不仅是由于美国人与犹太人关系密切,也是1957年出笼的“艾森豪威尔主义”要求美国向阿拉伯国家提供援助的结果。1970年初,一位观察家写道: 美国在30个国家驻军100万,是4个地区性防务联盟的成员,还积极参与另一个联盟的活动。此外,它与42个国家有双边防务条约,参加了53个国际组织,对全世界近100个国家提供军事或经济援助。

This was an array of commitments about which Louis XIV or Palmerston would have felt a little nervous. Yet in a world which seemed to be swiftly shrinking in size and in which each part appeared to relate to another, these step-by-step pledges all had their logic. Where, in a bipolar system, could Washington draw the line—especially after it was claimed that its earlier definition that Korea was not vital had been an invitation to the Communist attack of the following year?135 “This has become a very small planet,” Dean Rusk argued in May 1965. “We have to be concerned with all of it—with all of its land, waters, atmosphere, and with surrounding space. ”136

对如此繁重的国际义务,就是路易十四和巴麦尊也会感到不堪重负。可是,在一个迅速变小、各部分紧密相连的世界里,美国逐步负起这些责任也是合乎逻辑的。开始,美国人宣称朝鲜不很重要,但这却导致了共产党人的进攻。这种情况发生之后,在一个两极世界里,华盛顿应在何处建立自己的防线呢?1965年,迪安·腊斯克指出:“地球已变成一个很小的行星。我们应该关心它的一切,即关心它的陆地、水域、大气层和外层空间。”

If the projection of Soviet power and influence into the world outside was far less extensive, the years after Stalin’s death nonetheless saw noteworthy advances. Khrushchev, it is clear, wanted the Soviet Union to be admired, even loved, rather than feared; he also wanted to redirect resources from the military to agricultural investment and consumer goods. His general foreign-policy ideas reflected his hope for a “thaw” in the Cold War. Overruling Molotov, he removed Soviet troops from Austria; he handed back the Porkkala naval base to Finland and Port Arthur to China; and he improved relations with Yugoslavia, arguing that there were “separate roads to socialism” (a position as upsetting to many of his Presidium colleagues as it was to Mao Tse-tung). Although 1955 saw the formal establishment of the Warsaw Pact, in response to West Germany’s joining of NATO, Khrushchev was willing to open diplomatic relations with Bonn. He was also keen to improve relations with the United States, although his own volatility of manner and the by now chronic distrust with which Washington interpreted all Russian moves made a real détente impossible. In that same year, Khrushchev traveled to India, Burma, and Afghanistan. The Third World was from now on going to be taken seriously by the Soviet Union, just when more and more Afro-Asian states were gaining independence. 137

斯大林时期,苏联向国外输出军事力量的能力较弱,在世界各地的影响也较小;斯大林死后,苏联在各方面获得了引人注目的发展。显而易见,赫鲁晓夫想使苏联受到尊重,甚至热爱,而不想让人们害怕苏联。他还想减少军费,增加农业投资,多生产消费品。他的外交总政策反映了他有结束“冷战”的愿望。他不顾莫洛托夫的反对,从奥地利撤军,将波卡拉和中国旅顺两个海军基地分别归还芬兰和中国,并与南斯拉夫改善了关系,认为“通向社会主义的道路不只一条”(这一观点遭到了他的许多同事和毛泽东的反对)。尽管由于联邦德国加入北约,1955年华约正式成立,但赫鲁晓夫愿意与波恩建立外交关系。他还渴望与美国改善关系,尽管他反复无常的行为和华盛顿长期以来形成的对苏联的不信任感,使真正的缓和无法实现。同一年,赫鲁晓夫访问了印度、缅甸和阿富汗。从此以后,即亚非国家纷纷获得独立之际,苏联开始重视第三世界。

Little of this was as complete or smooth-going a transformation as the ebullient Khrushchev would have liked. In April 1956, that instrument of Stalinist control the Cominform had been dissolved. Embarrassingly, two months later the Hungarian uprising—a “separate road” away from socialism—had to be put down with Stalinist resolve. Quarrels with China multiplied and, as will be discussed below, produced a deep cleft in the Communist world. Détente foundered on the rocks of the U-2 incident (1960), the Berlin Wall crisis (1961), and then the confrontation with the United States over Soviet missiles in Cuba (1962). None of this, however, could turn back the Russian move toward world policy; the mere establishment of diplomatic relations with newly emergent countries and contact with their representatives at the United Nations made the growth of Soviet ties with the outside world inevitable. In addition, Khrushchev, eager to demonstrate the innate superiority of the Soviet system over capitalism, was bound to look for new friends abroad; his more pragmatic successors, after 1964, were interested in breaking the American cordon which had been placed around the USSR, and in checking Chinese influence. There were, moreover, many Third World countries eager to escape from what they termed “neocolonialism” and to institute a planned economy rather than a laissezfaire one—a preference which usually caused a cessation of western aid. All this fused to give Russian foreign policy a distinct “outward thrust. ”

然而,事物的变化并不像热情充沛的赫鲁晓夫希望的那样顺利或尽如人意。1956年4月,斯大林分子控制他国的机构——“共产党情报局”解散。令苏联人难堪的是,两个月后发生了匈牙利暴乱(匈牙利要走与社会主义“分道扬镳的道路”)。对此,克里姆林宫的斯大林分子必须坚决予以镇压。而且苏联与中国的争吵愈演愈烈。下面将要讨论,这将导致共产党世界的深刻分裂。苏联想与西方缓和的航船也触礁沉没,因为相继发生了U-2飞机事件(1960年)、柏林墙危机(1961年)和因苏联在古巴部署导弹而引起的与美国的对抗(1962年)。但是,所有这一切都无法改变苏联走向世界的趋势。只是与新独立的国家建立外交关系及在联合国与其代表接触,就可以使苏联与外部世界不可避免地加强联系。此外,赫鲁晓夫还热切希望向世界显示苏维埃制度对资本主义制度固有的优越性,这使他必然要寻求新的外国朋友。1964年后,比较务实的赫鲁晓夫的继任者们,热心于打破美国在苏联周围布设的封锁线并遏制中国的影响。另外,许多第三世界国家都急于摆脱它们所谓的“新殖民主义”统治,要求实行计划经济,而不是自由放任经济(这样做往往导致西方国家停止援助)。这一切的综合作用是,使苏联“向外扩张”的步伐明显加快。

This thrust began in a very decisive fashion in December 1953, by the signing of a trade agreement with India (neatly coinciding with Vice-President Nixon’s visit to New Delhi), followed up by the 1955 offer to construct the Bhilai steel plant, and then by lots of military aid; this was a connection to the most important of the Third World powers, it simultaneously annoyed the Americans and the Chinese, and it punished Pakistan for its membership in the Baghdad Pact. Almost at the same time, in 1955–1956, the USSR and Czechoslovakia began giving aid to Egypt, replacing Washington in the funding of the Aswan Dam. Soviet loans also went to Iraq, Afghanistan, and North Yemen. Pronounced anti-imperialist states in Africa, such as Ghana, Mali, and Guinea, were also encouraged by Moscow. In 1960, the great breakthrough occurred in Latin America, when the USSR signed its first trade agreement with Castro’s Cuba, then already becoming embroiled with an irritated United States. All this set a pattern which was not reversed by Khrushchev’s fall. Having waged a strident propaganda campaign against imperialism, the USSR quite naturally offered “friendship treaties,” trade credits, military advisers, and the rest to any newly decolonized nation. Russia could also benefit, in the Middle East, from the U. S. support of Israel (hence, for example, Moscow’s increasing aid to Syria and Iraq as well as Egypt in the 1960s); it could gain kudos by offering military and economic assistance to North Vietnam; even in distant Latin America, it could proclaim its commitment to national-liberation movements. In this struggle for world influence, the USSR had now come a long way from Stalin’s paranoid caution. 138

1953年12月,苏联与印度签订贸易协定(这与尼克松副总统访问新德里不谋而合);1955年帮助建设比莱钢厂,并提供大量军事援助。“向外扩张”伊始,苏联就与第三世界最重要的国家之一(印度)建立了联系,这不仅使中国人和美国人感到不快,对参加巴格达条约组织的巴基斯坦也是一种惩罚。几乎与此同时(1955~1956年),苏联和捷克斯洛伐克开始向埃及提供援助,取代美国为建设“阿斯旺水坝”提供资金。伊拉克、阿富汗和北也门得到了苏联的贷款。加纳、马里、几内亚等非洲坚决反帝的国家也得到了莫斯科的帮助。1960年,苏联与卡斯特罗领导的古巴签订了第一个贸易协定。这虽然使苏联的对外政策在拉丁美洲获得了重大突破,但也与被激怒的美国人结下了不解之怨,赫鲁晓夫下台并没有改变苏联的一套做法:首先大张旗鼓地进行反帝宣传,然后便与新独立的国家签订“友好条约”,向它们提供贸易贷款和军事顾问等。在中东,苏联还可从美国支持以色列中得到好处(例如,莫斯科于20世纪60年代增加了对叙利亚、伊拉克和埃及的援助)。另外,对北越提供经济和军事援助,也扩大了苏联的影响。就是对遥远的拉丁美洲的民族解放运动,莫斯科也声称有义务进行帮助。在争取扩大世界影响方面,现在的苏联同过分谨慎的斯大林相比已经走得很远。

But did this competition by Washington and Moscow for the affections of the rest of the globe, this mutual jostling for influence with the aid of treaties, credits, and weapons exports, mean that a bipolar world had indeed come into being, with everything significant in international affairs gravitating around the two opposing Schwerpunkte of the United States and the USSR? From the viewpoint of a Dulles or a Molotov, that indeed was how the world was ordered. And yet, even as these two blocs competed across the globe, and in areas unknown to both in 1941, they were meeting up with a quite different trend. For a Third World was just at this time coming of age, and many of its members, having at last thrown off the controls of the traditional European empires, were in no mood to become mere satellites of a distant superpower, even if the latter could provide useful economic and military aid.

华盛顿和莫斯科为了把世界各国争取到自己一边展开了激烈竞争,为扩大自己的势力范围竞相向国外提供援助、贷款和武器维修专家。这就说明在国际事务中,任何大事离开了美苏这两个对立的超级大国就无法解决的两极世界的确已经来临了吗?在杜勒斯和莫洛托夫看来,当时的世界的确如此。但是,即使在美苏两大集团争夺世界霸权之际,我们也可以看到,在1941年[4]美苏都未关注的地区有一种全新的发展趋势。此时,第三世界刚刚出现。它的许多成员,在终于摆脱了传统欧洲帝国的统治之后,不愿再沦为与自己相距甚远的那个超级大国的卫星国,虽然它可提供有益的经济和军事援助。

What was happening, in fact, was that one major trend in twentieth-century power politics, the rise of the superpowers, was beginning to interact with another, newer trend—the political fragmentation of the globe. In the Social Darwinistic and imperialistic atmosphere that had prevailed around 1900, it was easy to think that all power was being concentrated in fewer and fewer capitals of the world (see above, pp. 195–96) Yet the very arrogance and ambitiousness of western imperialism brought with it the seeds of its own destruction; the exaggerated nationalism of Cecil Rhodes, or the Panslavs, or the Austro-Hungarian military, provoked reactions among Boers, the Poles, the Serbs, the Finns; ideas of national self-determination, propagated to justify the unification of Germany and Italy, or the 1914 Allied decision to assist Belgium, seeped relentlessly eastward and southward, to Egypt, to India, to Indochina. Because the empires of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan had triumphed over the Central Powers in 1918 and had checked Wilson’s ideas for a new world order in 1919, these stirrings of nationalism were only selectively encouraged: it was fine to grant self-determination to the peoples of eastern Europe, because they were European and thus regarded as “civilized”; but it was not fine to extend these principles to the Middle East, Africa, or Asia, where the imperialist powers extended their territories and held down independence movements. The shattering of those empires in the Far East after 1941, the mobilization of the economies and recruitment of the manpower of the other dependent territories as the war developed, the ideological influences of the Atlantic Charter, and the decline of Europe all combined to release the forces for change in what by the 1950s was being called the Third World. 139

事实上,人们看到的是,20世纪强权政治中出现的重要动向之一——超级大国的崛起,开始与另一个新动向——全球性的政治分化发生联系。在1900年前后达尔文主义和帝国主义思潮占主导地位的社会环境中,人们想到和看到的是,世界权力越来越集中在少数几个国家。然而,西方帝国主义的骄横和狂妄却种下了导致自身毁灭的种子。塞西尔·罗德斯、泛斯拉夫主义者和奥匈帝国军界大肆宣扬民族主义,在布尔人、波兰人、塞尔维亚人和芬兰人中造成了深刻影响。作为德国、意大利统一和1914年协约国决定援助比利时的理论依据的民族自决论,很快向东向南传播到埃及、印度和印度支那。由于英国、法国、意大利和日本于1918年打败了德、奥、匈三国,并于1919年挫败了威尔逊关于建立世界新秩序的计划,民族主义行动只在部分地区得到鼓励。有些人认为,对东欧各国可赋予民族自治权,因为它们是欧洲“文明”国家;而不能把这种原则扩大到中东、非洲和亚洲各国。在非洲和亚洲等地区,帝国主义列强拥有大量殖民地,经常镇压民族独立运动。1941年后西方强国在远东利益的丧失,附属国随着战争的发展进行经济动员和征召新兵,大西洋宪章所造成的思想影响,以及欧洲各国的衰落,所有这些因素释放出来的能量都推动了第三世界(20世纪50年代才有这一术语)的发展变化。

But it was described as a “third” world precisely because it insisted on its distinction both from the American- and the Russian-dominated blocs. This did not mean that the countries which met at the original Bandung conference in April 1955 were free of all ties and obligations to the superpowers—Turkey, China, Japan, and the Philippines, for example, were among those attending the conference for whom the term “nonaligned” would have been inappropriate. 140 On the other hand, they all pressed for increased decolonization, for the United Nations to focus upon issues other than the Cold War tensions, and for measures to change a world which was still economically dominated by white men. When the second major phase of decolonization occurred, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the original members of the Third World movement could be joined by a large number of new recruits, smarting at the decades (or centuries) of foreign rule and grappling with the hard fact that independence had left them with a host of economic problems. Given the vast swelling of their numbers, they could now begin to dominate the United Nations General Assembly; originally a body of fifty (overwhelmingly European and Latin American) countries, the UN steadily changed into an organization of well over one hundred states with many new Afro-Asian members. This did not restrict the actions of the larger Powers that were permanent members of the Security Council and that possessed a veto—conditions insisted upon by a cautious Stalin. But it did mean that if either of the superpowers wished to appeal to “world opinion” (as the United States had done in getting the United Nations to aid South Korea in 1950), it had to gain the agreement of a body whose membership did not share the preoccupations of Washington and Moscow. Chiefly because the 1950s and 1960s were dominated by issues of decolonization, and by increasing calls to end “underdevelopment,” causes which the Russians adroitly espoused, this Third World opinion had a distinctly anti-western flavor, from the Suez crisis of 1956 to the later issues of Vietnam, the Middle East wars, Latin America, and South Africa. Even at the formal summits of the nonaligned countries, the emphasis was increasingly placed upon anticolonialism; and the geographical sitings of those meetings (Belgrade in 1961, Cairo in 1964, and Lusaka in 1970) symbolized this shift away from Eurocentered issues. The agenda of world politics was no longer exclusively in the hands of those powers possessing the greatest military and economic muscle. 141

第三世界国家是指坚持留在美苏控制的两个集团以外的国家。但这并不是说,所有参加1955年4月万隆会议的国家与两个超级大国都没有任何联系,对它们都不承担任何义务。例如,土耳其、中国、日本和菲律宾都参加了万隆会议,但把它们称作“不结盟”国家就不合适。另一方面,它们都主张加快非殖民化的进程,都要求联合国重视“冷战”以外的问题,都要求采取措施改变仍由白人统治的世界经济秩序。20世纪50年代末和60年代初,世界上发生了第二次非殖民化高潮,这使大量新独立的国家加入了第三世界国家的行列。这些新独立的国家曾遭受数十年乃至数百年的外国奴役,独立后又面临大量经济问题。第三世界国家的数量激增后,便开始控制联合国代表大会。开始,联合国只有50个成员国(绝大部分是欧洲和拉丁美洲国家),后来逐渐发展成一个拥有100多个国家的组织,其中许多新成员国来自亚洲和非洲。这并没使大国的行动受到制约,因为它们是安全理事会常任理事国,拥有否决权(这一权力是在谨慎的斯大林的坚持下确定的)。但是,这却意味着,如果任何一个超级大国希望得到“世界舆论”的支持(如美国1950年要求联合国支援南朝鲜),它就必须得到其他本来不赞成华盛顿和莫斯科观点的联合国成员国的支持。由于20世纪50年代和60年代非殖民化在国际事务中占主导地位,由于苏联巧妙支持的结束“经济落后”的呼声越来越高,第三世界的舆论具有浓厚的反西方色彩。这从1956年的苏伊士危机及之后的越南问题、拉美问题、南非问题和中东战争中都可看出。即使在不结盟国家最高级会议上,反殖民主义问题也被日益重视。这些会议的召开地点(1961年在贝尔格莱德,1964年在开罗,1970年在卢萨卡)也说明,人们关注的许多问题已不在欧洲。世界政治的控制权已不完全掌握在拥有最大军事、经济力量的国家的手中。