The Fissuring of the Bipolar World

两极世界的解体

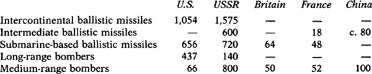

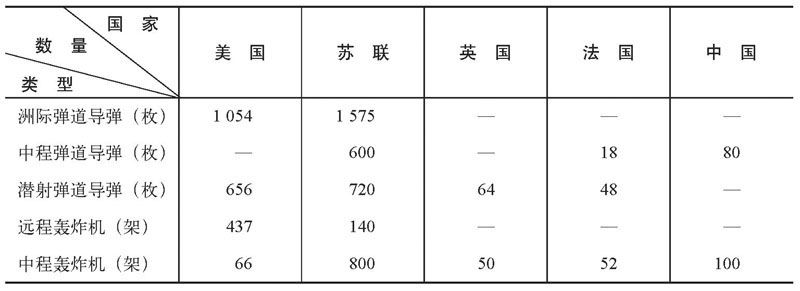

As the 1960s moved into the 1970s, there nevertheless remained good reasons why the Washington-Moscow relationship should continue to seem all-important in world affairs. Militarily, the USSR had drawn much closer to the United States, but both were still in a different league from everyone else. In 1974, for example, the United States was spending $85 billion and the USSR was spending $109 billion on defense, which was three to four times what was spent by China ($26 billion) and eight to ten times what was spent by the leading European states (U. K. $9. 7 billion; France, $9. 9 billion; West Germany, $13. 7 billion);145 and the American and Russian armed forces, of over 2 million and 3 million men, respectively, were much larger than those of the European states, and much better equipped than the 3 million men in the Chinese services. Both superpowers had over 5,000 combat aircraft, more than ten times the number possessed by the former Great Powers. 146 Their total tonnage in warships—the United States had 2. 8 million tons, the USSR 2. 1 million tons in 1974—was well ahead of Britain (370,000 tons), France (160,000 tons), Japan (180,000 tons), and China (150,000 tons). 147 But the greatest disparity lay in the numbers of nuclear delivery weapons, shown in Table 38.

在从20世纪60年代转入70年代时,华盛顿和莫斯科的关系在世界事务中继续起着举足轻重的作用。在军事上,苏联已经十分接近美国,并且它们依然不同于其他国家。例如,1974年,美国和苏联的防务开支分别达850亿美元和1090亿美元,分别相当于中国(260亿美元)的3~4倍,相当于欧洲主要国家(英国97亿美元,法国99亿美元,联邦德国137亿美元)的8~10倍;美苏两国的武装部队分别达200多万人和300多万人,比欧洲国家的规模大得多,比中国300万人的军队的装备精良得多。两个超级大国都有5000多架战斗机,比上述大国多10倍以上。1974年,两个超级大国的作战舰艇的总吨位分别达280万吨(美国)和210万吨(苏联),大大超过英国(37万吨)、法国(16万吨)、日本(18万吨)和中国(15万吨)。但是,最大的差距表现在核武器投射载具的数量方面,参看表38。

Table 38. Nuclear Delivery Vehicles of the Powers, 1974148

表38 大国核投射工具一览表(1974年)

So capable had each superpower become of obliterating the other (and anyone else besides)—a state of affairs quickly named MAD, or Mutually Assured Destruction—that they began to evolve arrangements for controlling the nuclear arms race in various ways. There was, following the Cuban missile crisis, the installation of a “hot line” to allow each side to communicate in the event of another critical occasion; there was the nuclear test-ban treaty of 1963, also signed by the United Kingdom, which banned testing in the atmosphere, under water, and in outer space; there was the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) of 1972, which set limits on the numbers of intercontinental ballistic missiles each side could possess and halted the Russian construction of an anti-ballistic-missile system; there was the extension of that agreement at Vladivostock in 1975, and, in the late 1970s, there were negotiations toward a SALT II treaty (signed in June 1979, but never ratified by the U. S. Senate). Yet these various measures of agreement, and the particular economic and domestic-political and foreign-policy motives which pushed each side into them, did not stop the arms race; if anything, the banning or limitation of one weapon system merely led to a transfer of resources to another area. From the late 1950s onward, the USSR steadily and inexorably increased its allocations to the armed forces; and while the pattern of American defense spending was distorted by its expensive war in Vietnam and then the public reaction against that venture, the long-term trend was also toward ever-higher totals. Every few years, newer weapon systems would be added: multiple warheads were fitted to each side’s rockets; missile-carrying submarines augmented each side’s navy; the nuclear stalemate in strategic missiles (provoking a European fear that the United States would not respond to a Soviet attack westward by unleashing long-range American missiles, since that could in turn provoke atomic strikes upon American cities) led to new types of medium-range or “theater” nuclear weapons, like the Pershing II and the cruise missiles being developed as answers to the Russian SS-20. The arms race and arms-control discussions of various sorts were obverse sides of the same coin; but each kept Washington and Moscow at the center of the stage.

每个超级大国都拥有如此巨大的抹掉对方(以及其他任何国家)的能力——因此而出现了很快被称之为“相互确保摧毁”(MAD)的事态——以致它们开始考虑做出安排,采取各种方式来控制这种核军备竞赛。在古巴导弹危机结束之后,它们建立了一条“热线”,以便使双方在发生另一次危机时能够进行通信;还搞了1963年核禁试条约(英国也在条约上签了字),禁止在大气层、水下和外层空间试验核装置;1972年搞了限制战略武器条约(第一阶段),通过这一条约限制各方拥有洲际弹道导弹的数量,使苏联停止建设反弹道导弹系统;1975年,双方在符拉迪沃斯托克(海参崴)又进一步扩大了这项条约的内容;到20世纪70年代末期,双方又举行了关于限制战略武器谈判第二阶段条约的会谈(1979年6月签署,但始终未获得美国参议院的批准)。可是,所有这些双方达成一致意见的措施,和推动双方同意采取这些措施的特定的经济、国内政治和对外政策的动机,并没有制止这场军备竞赛。即使说有什么效果,也只是禁止或限制一种武器,这不过导致各方把有关资源转用到另一领域而已。从20世纪50年代末期起,苏联稳步地、毫不手软地增加了对武装部队的拨款。虽然美国的防务开支方式因受越南这场代价昂贵的战争和随后公众反对那场冒险的影响,而发生了特殊变化,但其长期的趋势也是不断向高开支方向发展。每隔几年双方就会增加一批新武器系统,每一方的火箭都配备一批多弹头装置,海军增加一批导弹潜艇。而战略导弹方面出现的核僵持局面(这引起了欧洲人这样一种恐惧:美国不会用它的远程导弹回击苏联指向西方的进攻,因为那会招致苏联对美国城市的原子打击),导致美国发展“潘兴Ⅱ”和巡航导弹一类的新型中程或“战区”核武器,来对付苏联的SS-20式导弹。这场军备竞赛和各种军备控制讨论,不过是同一事物的两种表现而已,但每一种表现都使华盛顿和莫斯科站在舞台的中心。

In other fields, too, their rivalry appeared central. As mentioned earlier, one of the more notable features of the Soviet arms buildup since 1960 was the enormous expansion of its surface fleet—physically, as it constructed ever more powerful, missile-bearing destroyers and cruisers, then medium-sized helicopter carriers, then aircraft carriers;149 and geographically, as the Soviet navy began to send more and more vessels into the Mediterranean and farther afield, to the Indian Ocean, West Africa, Indochina, and Cuba, where it was able to use an increasing number of bases. This last development reflected a very significant extension of American- Russian rivalries into the Third World, chiefly because of Moscow’s further success in breaking into regions where foreign influence had hitherto been a western monopoly. The continued tension in the Middle East, and especially the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973 (where American arms supplies to Israel were decisive), meant that various Arab states—Syria, Libya, Iraq—would remain looking to Moscow for assistance. The Marxist regimes of Southern Yemen and Somalia provided naval-base facilities to the Russian navy, giving it a new maritime presence in the Red Sea. But, as usual, breakthroughs were accompanied by setbacks: Moscow’s apparent preference for Ethiopia led to the expulsion of Soviet personnel and ships from Somalia in 1977, just a few years after the same had happened in Egypt; and Russian advances in this area were countered by the growth of the American presence in Oman and Diego Garcia, naval-base rights in Kenya and Somalia, and increased arms shipments to Egypt, Saudia Arabia, and Pakistan. Farther to the south, however, the Soviet-Cuban military assistance to the MPLA forces in Angola, the frequent attempts of the Soviet-aided Libyan regime of Qaddafi to export revolution elsewhere, and the presence of Marxist governments in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Guinea, Congo, and other West African states suggested that Moscow was winning in the struggle for global influence. Its own military move into Afghanistan in 1979— the first such expansion (outside eastern Europe) since the Second World War—and Cuba’s encouragement of leftist regimes in Nicaragua and Grenada furthered this impression that the American-Russian rivalry knew no limits, and provoked additional countermoves and increases in defense spending on Washington’s part. By 1980, with a new Republican administration denouncing the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” against which massive defense forces and unbending policies were the only answer, little seemed to have changed since the days of John Foster Dulles. 150

在其他领域,这两个对手也以中心角色的面目出现。如前所述,苏联自1960年以来扩充军备的更加令人瞩目的方面之一,是大规模扩充其水面舰队——从其实体上看,建造威力更加强大的导弹驱逐舰和巡洋舰,然后是建造中型直升机母舰和固定翼飞机航空母舰;从地理上看,苏联海军开始向地中海和更远的印度洋、西非、印度支那和古巴(在这些地方可供苏联海军部队使用的基地越来越多)派出越来越多的海军舰艇。后面这种事态的发展,反映出美苏竞争已向第三世界显著扩展,这主要是因为苏联进一步成功地打入了那些过去只有西方才拥有势力的地区。中东局势的继续紧张化,尤其是1967年和1973年爆发的阿以战争(在这些战争中,美国对以色列的武器供应具有决定性意义),意味着一些阿拉伯国家(叙利亚、利比亚、伊拉克)一直指望莫斯科提供援助。也门和索马里的马克思主义政权向苏联海军提供了海军基地设施,使它在红海获得了新的海上势力范围。但是,像往常一样,新的突破也伴之以新的挫折:莫斯科对埃塞俄比亚的明显的偏爱导致苏联人及其舰船在1977年被赶出了索马里;几年以后,在埃及又发生了同样的事态;苏联在这一地区的进展,受到了美国的抵抗,后者在阿曼和迪戈加西亚增加了兵力,在肯尼亚和索马里取得了海军基地权,并且向埃及、沙特阿拉伯和巴基斯坦增运武器。然而,在更远的南方地区,苏联—古巴对安哥拉人民解放运动部队的军事援助,受到苏联支持的利比亚卡扎菲政权不时企图向其他国家输出革命,马克思主义政府在埃塞俄比亚、莫桑比克、几内亚、刚果和其他西非国家的出现,都表明苏联在这场争夺全球势力范围的斗争中正在步步获胜。苏联1979年在军事上介入阿富汗——这是自第二次世界大战以来苏联首次(在东欧以外地区)进行这种扩张——以及古巴对尼加拉瓜和格林纳达左倾政权的鼓励和支持,进一步加深了这种印象:美苏之间的竞争是无止境的。这引起了美国方面新的对抗行动以及防务开支的增加。到1980年,新上台的共和党政府谴责苏联,说它是一个“邪恶的帝国”,只有用庞大的防御部队和不屈不挠的政策来对付它,但似乎自约翰·福斯特·杜勒斯任国务卿的岁月以来,几乎一切都没有发生什么变化。

Yet, for all this focus upon the American-Russian relationship and its many ups and downs between 1960 and 1980, other trends had been at work to make the international power system much less bipolar than it had appeared to be in the earlier period. Not only had the Third World emerged to complicate matters, but significant fissures had occurred in what had earlier appeared to be the two monolithic blocs dominated by Moscow and Washington. The most decisive of these by far, with repercussions which are difficult to measure fully even at the present time, was the split between the USSR and Communist China. In retrospect, it may seem self-evident that even the allegedly “scientific” and “universalist” claims of Marxism would founder on the rocks of local circumstances, indigenous cultural strengths, and differing stages of economic development—after all, Lenin himself had had to make massive deviations from the original doctrine of dialectical materialism in order to secure the 1917 Revolution. And some foreign observers of Mao’s Communist movement in the 1930s and 1940s were aware that he, at least, was not inclined to adhere slavishly to Stalin’s dogmatic position toward the relative importance of workers and peasantry. They were also aware that Moscow, in its turn, had been less than wholehearted in its support of the Chinese Communist Party and had, even as late as 1946 and 1948, tried to balance it off against Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists. This, in the USSR’s view, would avoid the creation of “a vigorous new Communist regime established without the assistance of the Red Army in a country with almost three times the population of Russia [which] would inevitably become a competing pole of attraction within the world Communist movement. ”151

可是,在美苏关系面临所有这一切重大事态和1960~1980年发生许多曲折变化的同时,也出现了另一些有影响的趋势,使得国际力量体系比起较早时期的两极化,在程度上大大削弱了——不仅第三世界的出现使事态进一步复杂化,而且由苏联和美国分别控制的先前铁板一块的两大集团内部,也发生了重大分化。其中,最具有决定性意义的是苏联同中国之间的分裂,其影响即使在现在也难以做出充分的估计。回顾起来,事情似乎不言自明:马克思主义科学和普遍性原理要以现实的具体场合、固有的文化力量和经济发展的不同阶段为依据。列宁也曾对辩证唯物主义原理做过许多重大完善,以适应1917年革命的需要。一些研究20世纪30年代和40年代毛泽东的共产主义运动的外国观察家清楚地了解,毛泽东没有恪守斯大林关于工人阶级和农民阶级不同重要地位的教条主义立场。他们还清楚地知道,莫斯科方面并非那么全心全意地支持中国共产党,甚至到1946年和1948年,还试图缓和中国共产党对国民党蒋介石的态度。从苏联的观点来看,这样就可以防止“在没有红军的援助下,在一个人口几乎相当于苏联3倍的国家里建立一个有生气的新共产党政权,而一旦出现这种情况,这个新政权就会不可避免地变成在世界共产主义运动中与苏联相竞争的具有吸引力的角色”。

Nonetheless, the sheer extent of the split took most observers by surprise, and was for many years missed by a United States aroused by the fear of a global Communist conspiracy. Admittedly, the Korean War and the subsequent Chinese-American jockeying over Taiwan took attention from the lukewarm state of the Moscow- Peking axis, in which Stalin’s relatively small amounts of aid to China were always tendered for a price which emphasized Russia’s privileges in Mongolia and Manchuria. Although Mao was able to redress the balance in his 1954 negotiations with the Russians, his hostility to the United States over the offshore islands of Quemoy and Matsu and his more extreme adherence (at least at that time) to the belief in the inevitability of a clash with capitalism made him bitterly suspicious of Khrushchev’s early détente policies. From Moscow’s viewpoint, however, it seemed foolish in the late 1950s to provoke the Americans unnecessarily, especially when the latter had a clear nuclear advantage; it would also be a setback, diplomatically, to support China in its 1959 border clash with India, which was so important to Russia’s Third World policy; and it would be highly unwise, given the Chinese proclivity to independent action, to aid their nuclear program without getting some controls over it—all of these being regarded as successive betrayals by Mao. By 1959, Khrushchev had canceled the atomic agreement with Peking and was proffering India far larger loans than had ever been given to China. In the following year, the “split” became open for all to see at the World Communist Parties’ meeting in Moscow. By 1962–1963, things were worse still: Mao had denounced the Russians for giving in over Cuba, and then for signing the partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty with the United States and Britain; the Russians had by then cut off all aid to China and its ally Albania and increased supplies to India; and the first of the Sino- Soviet border clashes occurred (although never as serious as those of 1969). More significant still was the news that in 1964 the Chinese had exploded their first atomic bomb and were hard at work on delivery systems. 152

尽管如此,苏中之间完全分裂的程度使大多数观察家感到十分奇怪,并且为多年来因害怕出现全球共产主义阴谋而深感不安的美国所迷惑不解。应当承认,朝鲜战争及之后发生的中美在中国台湾问题上的态度,转移了人们对莫斯科—北京轴心的冷淡状态的注意力,在这个轴心中,斯大林给中国的为数不多的援助总是以某种代价——强调苏联在蒙古和中国东北的特权——来补偿。虽然毛泽东能够在1954年同苏联人举行的会谈中重新恢复平衡,但他在沿海金门和马祖诸岛问题上对美国表现的敌意,以及他认为(至少在那时是这样)将不可避免与资本主义进行决斗的信仰,使他非常怀疑赫鲁晓夫早期的缓和政策。但是,从苏联的观点来看,在20世纪50年代末期不必要地刺激美国似乎是愚蠢的,尤其是当后者拥有明显的核优势时;在中国1959年同印度发生的边界冲突中支持中国,也会给苏联在外交上带来挫折,而这一点对苏联的第三世界政策具有非常重要的意义;此外,苏联认为支援中国的核计划而不对其计划施加某些控制,也是非常不明智的。毛泽东认为所有这一切都是苏联(对中国)的接二连三的背叛。到1959年,赫鲁晓夫取消了同中国的原子能协议,向印度提供的贷款,远比曾向中国提供的多得多。第二年,在莫斯科举行的世界共产党会议上,这场“分裂”终于公开化了。到1962~1963年,事态进一步恶化:毛泽东谴责苏联人在古巴问题上的屈服,然后谴责他们同美英两国一起签署部分核禁试条约;那时,苏联人中断了对中国及其盟友阿尔巴尼亚的一切援助,增加了对印度的物资供应;首次发生了中苏边界冲突(尽管没有像1969年那几次那么严重)。更加重要的是这样的消息:1964年,中国人爆炸了他们的第一颗原子弹,正在努力地研制运载系统。

Strategically, this split was the single most important event since 1945. In September 1964, Pravda readers were shocked to see a report that Mao was not only claiming back the Asian territories which the Chinese Empire had lost to Russia in the nineteenth century, but also denouncing the USSR for its appropriations of the Kurile Islands, parts of Poland, East Prussia, and a section of Rumania. Russia, in Mao’s view, had to be reduced in size—in respect to China’s claims, by 1. 5 million square kilometers!153 How much the opinionated Chinese leader had been carried away by his own rhetoric it is hard to say, but there was no doubt that all this— together with the border clashes and the development of Chinese atomic weapons— was thoroughly alarming to the Kremlin. Indeed, it is likely that at least some of the buildup of the Russian armed forces in the 1960s was due to this perceived new danger to the east as well as the need to respond to the Kennedy administration’s defense increases. “The number of Soviet divisions deployed along the Chinese frontier was increased from fifteen in 1967 to twenty-one in 1969 and thirty in 1970”—this latter jump being caused by the serious clash at Damansky (or Chenpao) island in March 1969. “By 1972 forty-four Soviet divisions stood guard along the 4,500-mile border with China (compared to thirty-one divisions in Eastern Europe), while a quarter of the Soviet air force had been deployed from west to east. ”154 With China now possessing a hydrogen bomb, there were hints that Moscow was considering a preemptive strike against the nuclear installation at Lop Nor—causing the United States to make its own contingency plans, since it felt that it could not allow Russia to obliterate China. 155 Washington had come a long way since its 1964 ponderings about joining the USSR in “preventative military action” to arrest China’s development as a nuclear power!156

从战略上看,这一分裂是1945年以来发生的最重大的一次事件。1964年9月,苏联《真理报》的读者们十分震惊地看到这样一则报道:毛泽东不但要求收回中国在19世纪落到俄国人手中的亚洲领土,而且还谴责苏联对千岛群岛、波兰一部分领土、东普鲁士和罗马尼亚一部分领土的占有。毫无疑问,所有这一切——加之边界冲突和中国原子武器的发展——都是向克里姆林宫发出的不折不扣的警报信号。的确,20世纪60年代苏联武装部队的扩充很可能至少有一部分是针对这种可见的来自东方的新危险的,也是为了对肯尼迪政府加强防务的行动做出必要的反应。“苏联沿中国边境部署的作战师数量由1967年的15个增加到1969年的21个、1970年的30个”,1970年战斗师数量的激增是由于1969年3月珍宝岛发生的那场严重的冲突而引起的。“到1972年,苏联在同中国长达4500英里的边界线上共部署了44个师(相比之下,在东欧才有31个师),同时苏联空军的1/4也由西方向东方部署。”随着中国已拥有氢弹的现实,有迹象表明苏联在考虑对中国设在罗布泊的核设施实施一次预防性的打击——而这又促使美国制订自己的应急计划,因为美国感到不能容许苏联消灭中国。自美国在1964年考虑过同苏联一道用“预防性的军事行动”制止中国发展成为一个核大国以来,华盛顿的看法已经发生了一个巨大的转变!

This was hardly to say that Mao’s China had emerged as a full-fledged third superpower. Economically, it had enormous problems—which were exacerbated by its leader’s decision to initiate the “Cultural Revolution,” with all its accompanying discontinuities and uncertainties. And while it might boast the largest army in the world, its people’s militias were not likely to be a match for Soviet motor rifle divisions. China’s navy was negligible compared with the expanding Russian fleet; its air force, though large, chiefly consisted of older planes; and its nuclear-delivery system was but in its infancy. Nonetheless, unless the USSR was prepared to run the risk of provoking the Americans and offending world opinion by launching a massive nuclear attack upon China, any fighting at a lesser level could quickly produce enormous casualties—which the Chinese seemed willing to accept, but Russian politicians in the Brezhnev era were less keen about. It was therefore not surprising that as Russo-Chinese relations worsened, Moscow should not only have shown interest in nuclear-arms-limitation talks with the West but also have quickened the pace of improving relations with countries like the Federal Republic of Germany, which under Willy Brandt seemed much more willing to foster detente than in Adenauer’s days.

这并不能说当时的中国已经成长为羽翼丰满的第三个超级大国。从经济上说,中国还有许多问题——而中国的领导人决定发动“文化大革命”,又使这些问题更加严重起来,随之使经济发展中断并处于不稳定之中。尽管中国可以夸耀它有世界上规模最大的陆军,但它的民兵可能不是苏军摩托化步兵师的对手。同苏联正在扩充的舰队比较起来,中国的海军微不足道;中国的空军虽然规模很大,但主要是由较旧的飞机组成的;中国的核发射系统正处于初创阶段。尽管如此,除非苏联准备不惜冒险刺激美国人和不顾世界舆论,对中国发动大规模的核进攻,否则,任何较小规模的作战行动都可能迅速造成巨大的伤亡——中国人能够接受这一点,但勃列日涅夫时代的苏联政治家们却并不太愿意这样做。所以,毫不奇怪,随着中苏关系的进一步恶化,莫斯科理所当然地要不仅表示出同西方举行限制核军备会谈的兴趣,而且还加快了同联邦德国一类的国家改善关系的步伐(同阿登纳时期相比,维利·勃兰特领导下的联邦德国似乎更加乐于搞缓和)。

In the political and diplomatic arena, the Sino-Soviet split was even more embarrassing to the Kremlin. Although Khrushchev himself had been willing to tolerate “separate roads to socialism” (always provided those routes were not too divergent!), it was quite another thing for the USSR to be openly accused of having abandoned true Marxist principles; for its satellites and clients to be encouraged to throw off the Russian “yoke”; and for its diplomatic efforts in the Third World to be complicated by Peking’s rival aid and propaganda—the more especially since Mao’s brand of peasant-based Communism appeared often more appropriate than the Russian emphasis upon an industrial proletariat. This did not mean that the Soviet Empire in eastern Europe was in any real danger of following the Chinese lead— only the eccentric regime in Albania did so. 157 But it remained embarrassing to Moscow to be denounced by Peking for suppressing the Czech liberalization reforms in 1968, and again for its actions against Afghanistan in 1979. In the Third World, moreover, China was somewhat better placed to block Russian influence: it competed hard in North Yemen; it made much of its railway construction scheme in Tanzania; it criticized Moscow for failing to give sufficient support to the Vietminh and the Vietcong against the United States; and as it renewed relations with Japan, it warned Tokyo about a too-heavy economic collaboration with the Russians in Siberia. Once again, this was rarely an equal struggle—Russia could usually offer much more to Third World states in terms of credits and advanced arms, and could also project its influence by using Cuban and Libyan surrogates. But simply having to compete with a fellow Marxist state as well as with the United States was altogether more upsetting than the predictable, bipolar rivalries of two decades earlier.

在政治与外交领域,中苏的分裂甚至使克里姆林宫更加进退两难。虽然赫鲁晓夫本人一直愿意容忍“沿各自的道路走向社会主义”,但是,要让苏联被人们谴责为已放弃真正的马克思主义的原则,让苏联的卫星国和仆从国受到鼓舞来脱离它的“束缚”,让它在第三世界的外交努力因中国的敌对性援助和宣传而变得复杂起来(尤其是自毛泽东的以农民为基础的社会主义比苏联对工业无产阶级作用的强调往往更加赢得人心以来,情况更是如此),却是十分不同的另一码事。这并不意味着东欧部分的苏联卫星国已真的处于追随中国的危险之中——只有阿尔巴尼亚偏离轨道的政权这么干了。但是,中国针对苏联1968年对捷克斯洛伐克的解放性改革运动采取的镇压行动和苏联1979年反对阿富汗的行动的谴责,却一直使苏联难堪。而且,在第三世界,中国在阻止苏联扩大自己的影响方面还处于较有利的地位:中国在北也门展开了激烈的竞争;在坦桑尼亚完成了很大一部分铁路建设工程计划;批评苏联未能在越盟和越共对美国的斗争中向它们提供充分的支援;随着中日关系的恢复,中国警告日本不要在西伯利亚同苏联进行过分的经济合作。情况再一次表明,这很难说是一场势均力敌的斗争——苏联通常能够向第三世界国家提供多得多的贷款和先进的武器,还能够利用古巴和利比亚的代理人扩大自己的影响。但是,被迫同一个马克思主义伙伴国和美国进行竞争,毕竟要比20年前那种可以预测的两极斗争更加令人烦恼。

In all sorts of ways, then, China’s assertive and independent line made diplomatic relationships more complicated and baroque, especially in Asia. The Chinese had been stung by Moscow’s wooing of India and even more by its dispatch of military supplies to New Delhi following Sino-Indian border clashes; not surprisingly, therefore, Peking gave support to Pakistan in its own clashes with India, and was strongly resentful of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. China was further alienated by Moscow’s support for North Vietnam’s expansion in the late 1970s, by the latter’s entry into Comecon, and by the increasing Russian naval presence in Vietnamese ports. When Vietnam invaded Cambodia in December 1978, China engaged itself in bloody and not very successful border clashes with its southern neighbor, which was in turn being heavily supplied with Russian weapons. By this stage, Moscow was even looking more favorably toward the Taiwan regime, and Peking was urging the United States to increase its naval forces in the Indian Ocean and western Pacific, to counter the Russian squadrons. A mere twenty years after China was criticizing the USSR for being too soft toward the West, it was pressing NATO to increase its defenses and warning both Japan and the Common Market against strengthening economic ties with Russia!158

这样,中国强硬的独立路线在各个方面使外交关系变得更加复杂化和难捉摸,尤其是在亚洲。苏联向印度“求爱”大大刺痛了中国人;它在中印边界冲突之后向新德里赶运军用补给物资的行动更进一步刺痛了中国人。所以,中国在巴基斯坦同印度发生冲突时向巴基斯坦提供支援,并对俄国人入侵阿富汗表示强烈愤慨,便毫不奇怪了。苏联在20世纪70年代末期支持北越扩张,北越加入经济互助委员会,以及苏联海军越来越多地出现在越南的港口,使它进一步疏远了中国。当越南在1978年12月入侵柬埔寨时,中国同它的南部邻国进行了边界战争,这场战争反而使越南得到了苏联的大量武器援助。到这个时候,苏联甚至更加讨好中国台湾,中国则催促美国增加其在印度洋和西太平洋的海军部队,以对付苏联的海军分舰队。

By comparison, the dislocations which occurred in the western camp from the early 1960s onward, caused chiefly by de Gaulle’s campaign against American hegemony, were nowhere near as serious in the long term—although they certainly added to the impression that the two blocs were breaking up. With strong memories of the Second World War still in mind, de Gaulle seethed at the fact that he was treated as less than equal by the United States; he resented American policy during the Suez crisis in 1956, not to mention Dulles’s habit of threatening a nuclear conflagration over issues like Quemoy. Although de Gaulle had more than enough to keep him busy for several years after 1958 as he sought to extricate France from Algeria, even at that time he criticized western Europe’s subservience (as he saw it) to American interests. Like the British a decade earlier, he saw in nuclear weapons a chance to preserve Great Power status; when news of the first French atomic test of 1960 arrived, the general called out, “Hooray for France—since this morning she is stronger and prouder. ”159 Determined to have France’s nuclear deterrent totally independent, he angrily rejected Washington’s offer of a Polaris missile system similar to Britain’s because of the conditions the Kennedy administration attached to it. While this meant that France’s own nuclear-weapons program would consume a far greater proportion of the total defense budget (perhaps as much as 30 percent) than it did elsewhere, de Gaulle and his successors felt the price was worth paying. At the same time, he began to pull France out of the NATO military structure, expelling that organization’s HQ from Paris in 1966 and closing down all American bases on French soil. In parallel with this, he sought to improve France’s relations with Moscow—where his actions were warmly applauded—and he ceaselessly proclaimed the need for Europe to stand on its own feet. 160

相比之下,西方阵营从20世纪60年代初开始主要因戴高乐反对美国霸权的运动而引起的不和,从长远看却没有那么严重——尽管这些不和肯定增加了这样的印象:两个集团的关系正在破裂。由于对第二次世界大战的记忆仍然很强烈,戴高乐对下面这一事实十分愤慨:美国没有平等地对待他;他对美国在1956年苏伊士运河危机期间的政策表示愤恨,更不要提杜勒斯在类似金门事件这类问题上动不动就以核战火相威胁了。虽然1958年后戴高乐在寻求法国从阿尔及利亚撤出这件事情上足以忙碌好几年,但即使在那时,他也批评西欧屈从(他自己的看法)美国的利益。像英国10年前一样,他看到核武器能够提供一种保持大国地位的机会。当法国1960年首次试验原子武器的消息传到这位将军耳里时,他高呼:“法国万岁!从今天早上起,它更加强大了,更加骄傲了。”他决心使法国的核威慑力量保持完全的独立,愤怒地拒绝了华盛顿向法国提供类似给英国的那种“北极星”导弹系统的建议,因为肯尼迪政府附加了不能接受的条件。虽然这意味着法国自己的核武器计划要耗费整个防务预算的很大一部分(可能多达30%),但戴高乐及其后继者却感到这一代价是值得的。与此同时,他着手使法国脱离北约组织的军事结构,在1966年把该组织的总部从巴黎赶走,关闭了所有在法国领土上的美国基地。与此相配合,他设法改善了法国同苏联的关系;在莫斯科,他的行动受到了热烈的欢迎。他孜孜不倦地宣传欧洲自立的必要性。

De Gaulle’s spectacular actions did not rest merely on Gallic rhetoric and cultural pride. Boosted by Marshall Plan aid and other American grants, and benefiting from Europe’s general economic recovery after the late 1940s, the French economy had grown swiftly for almost two decades. 161 The colonial wars in Indochina (1950– 1954) and Algeria (1956–1962) diverted French resources for a while, but not irremediably. Having negotiated very favorable terms for its national interests at the time of the formation of the European Economic Community in 1957, France was able to benefit from this larger market while restructuring its own agriculture and modernizing its industry. Although critical of Washington and firmly preventing British entry into the EEC, de Gaulle effected a dramatic reconciliation with Adenauer’s Germany in 1963. And all the time he spoke of a need for Europe to stand on its own feet, to be free of superpower domination, to remember its glorious past and to cooperate—with France naturally showing the lead—in the pursuit of equally glorious destiny. 162 These were heady words, but they evoked a response on both sides of the Iron Curtain, and appealed to many who disliked both the Russian and American political cultures, not to mention their respective foreign policies.

戴高乐令人惊奇的行动并不只是靠高卢人的花言巧语和文化骄傲搞起来的。法国的经济在马歇尔计划的援助和其他美国馈赠支持下获得了发展,并受益于20世纪40年代末期之后欧洲的一般经济恢复,因而在近20年间有了迅速的增长。虽然在印度支那(1950~1954年)和阿尔及利亚(1956~1962年)的殖民战争一时转移了法国资源的使用方向,但这并非不可纠正的。在1957年组织欧共体时,法国通过谈判争得了符合国家利益的极为有利的条件,因而得以受益于这一规模较大的市场,与此同时着手改组本国的农业和进行工业现代化。戴高乐对美国非常苛刻,坚决阻止英国加入欧共体,但在1963年同阿登纳领导下的联邦德国进行了戏剧性的和解。他经常鼓吹欧洲有必要自立,脱离超级大国的控制,记住自己过去的光荣和合作(自然由法国带头),追求平等的光荣命运。这些都是很有分量的语言,这些语言在“铁幕”两边都引起了反响,为许多厌恶苏美政治文化的人所欢迎,更不用说厌恶苏美对外政策的人了。

By 1968, however, de Gaulle’s own political career had been undermined by the students’ and workers’ revolt. The strains caused by modernization and the still relatively modest size of the French economy (3. 5 percent of world manufacturing production in 1963)163 meant that the country simply was not strong enough to play the influential role that the general had envisaged; and whatever the special agreements he proffered to the West Germans, the latter dared not abandon their tight links with the United States, upon which, in the final resort, Bonn politicians knew they heavily depended. Moreover, Russia’s ruthless crushing of the Czech reforms in 1968 showed that the eastern superpower had no intention of letting the countries in its sphere evolve their own policies, let alone become part of a Frenchled, European-wide confederation.

然而,到1968年,戴高乐本人的政治生涯因学生和工人的革命而受到了影响。现代化所引起的紧张情况和法国经济仍处于相对的中等规模(1963年占世界制造业产量的3.5%),意味着国家没有足够强大的实力来扮演此位将军已设想好的发挥影响的角色;尽管他向联邦德国人提出了特别协议,但后者不敢放弃它同美国的紧密联系,波恩的政治家们也知道,作为最后的一着,美国始终是他们所着重依赖的。而且,1968年苏联无情地粉碎捷克斯洛伐克的改革表明,这个东方的超级大国不打算让它势力范围内的国家按照自己的政策行事,更不要说让它们成为以法国为首的、全欧洲范围的联合组织的成员了。

Nonetheless, for all his hubris, de Gaulle had symbolized and accelerated trends which could not be stopped. Despite their military weaknesses compared with the United States and the USSR, the armed forces of the western European states were much larger and stronger, relatively speaking, than they had been in the post-1945 years; two of them had nuclear weapons and were developing delivery systems. Economically, as will be discussed in more detail below, the “recovery of Europe” had succeeded splendidly. What was more, despite Russia’s 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, the era of the Cold War division of Europe into hermetically sealed blocs was being weakened. Willy Brandt’s spectacular policy of reconciliation with Russia, with Poland and Czechoslovakia, and especially with the (at first very reluctant) East German regime between 1969 and 1973, chiefly on the basis of accepting the 1945 boundaries as permanent, inaugurated a period of blossoming East-West contacts. Western investments and technology flowed across the Iron Curtain, and this “economic détente” spilled over into cultural exchanges, the Helsinki Accords (of 1975) on human rights, and efforts to avert future military misunderstandings and to achieve mutual force reductions. To all this the superpowers, for their own good reasons, and with some inevitable reservations (especially on the Soviet side), gave their blessing. But perhaps the most significant fact had been the persistent pressures by the Europeans themselves to effect the rapprochement; even when relations cooled between Moscow and Washington, therefore, it was going to be extremely difficult in the future for either the USSR or the United States to halt this process. 164

纵然如此,戴高乐过分自信的行为已经象征和加速了事态势不可当的发展。同美苏比较起来,西欧国家在军事上是软弱的,但它们的武装力量同1945年以后的那几年相比仍然强大得多,其中两个国家拥有核武器,并正在发展投射系统。从经济上说,正如后面将详细讨论的,“欧洲的复兴”已经获得了光辉的成就。事情还不只此,尽管苏联在1968年入侵捷克斯洛伐克,但“冷战”时代把欧洲分裂为不透气的封闭集团的格局正在受到削弱。维利·勃兰特奉行的令人注目的同苏联、波兰和捷克斯洛伐克,尤其是1969年和1973年同民主德国政权(起初是很不情愿的)的和解政策(主要在承认1945年的国界为永久性国界的基础上进行和解),开创了东西方频繁接触的活跃时期。西方的投资和技术穿过“铁幕”渗入进去,并且这种“经济上的缓和”还扩展到文化交流、“赫尔辛基人权公约”(1975年)、防止发生未来军事误解方面的交流活动,以及实现共同裁军等领域。超级大国对所有这一切都给予了支持,这是因为它们本身具有一些适当的理由,并且也不可避免地作了某些保留,尤其是苏联方面。但是,可能最重要的事实是欧洲本身在推行友好睦邻关系方面所施加的持久的压力。因此,甚至当苏联和美国之间的关系变得冷淡的时候,不管是苏联还是美国,在将来都极难制止这一进程。

Of the two, the Americans were in a much better position than the Russians to adjust to the new, pluralistic international environment. Whatever de Gaulle’s anti- American gestures, they were nowhere near the seriousness of Sino-Soviet border clashes, elimination of bilateral trade, ideological invective, and diplomatic jostling across the globe which, by 1969, were causing some observers to argue that a Russo-Chinese war was inevitable. 165 However much American administrations resented France’s actions, they hardly needed to redeploy their armed forces because of such quarrels. In any case, NATO was still permitted to retain overflight rights and the fuel-oil pipeline which ran across France, and Paris kept up its special defense arrangements with West Germany—so that its troops, too, would be available if the Warsaw Pact forces struck westward. Finally, of course, it had been a fundamental axiom of American policy after 1945 that a strong and independent Europe (that is, independent from Russian domination) was in the United States’ long-term interests and would help to reduce its defense burdens—even while admitting that such a Europe might also be an economic and perhaps a diplomatic competitor. It was for that reason that Washington had encouraged all moves toward European integration, and was urging Britain to join the EEC. By contrast, Russia might begin not only to feel insecure militarily if a powerful European confederation emerged in the West, but also to worry about the magnetic pull which such a body would exercise upon the Rumanians, Poles, and other satellite peoples. A policy of selective détente and economic cooperation with western Europe by Moscow was one thing, partly because it could bring technological and trading benefits, partly because it might draw the Europeans further away from the Americans, and partly because of the China challenge on Russia’s Asian front. In the longer term, however, a prosperous, resurgent Europe which would overshadow the USSR in all respects except the military (and perhaps become strong in that area, too) could hardly be in Russia’s best interests. 166

就两个超级大国来说,在使自己适应这种新的、多元性的国际环境方面,美国人所处的地位比苏联人有利得多。不管戴高乐采取何种反美姿态,都比不上下述事件的严重性:中苏边界冲突、取消双边贸易、意识形态方面的争吵,以及全球性的外交上的斗争(到1969年,这一点促使某些观察家认为中苏之间发生战争是不可避免的)。不管美国政府多么憎恨法国的行为,但它几乎不需要因为这种争吵重新部署自己的武装部队。不管怎样,北约组织仍被允许保留穿过法国的飞行过境权和输油管系统;巴黎保持着同联邦德国的特殊防务安排。所以,一旦发生华约军队向西方进攻的情况,法国的部队也可供使用。最后,当然要提到1945年后美国一直遵循的一条基本格言:一个强大的和独立的欧洲(即不受苏联控制的欧洲)是符合美国长远利益的,并且会有助于减轻美国的防务负担——即使承认这样一个欧洲也可能成为它经济上和可能的外交上的竞争对手的情况下,也是如此。正因为如此,美国一直鼓励欧洲一体化的举措,并敦促英国加入欧共体。相比之下,苏联可能不仅开始感到如果西方出现一个强大的欧洲联合体,它在军事上将不安全,而且开始对这一实体可能对罗马尼亚人、波兰人和其他卫星国人民所产生的吸引力感到不安。事实上,苏联推行了同西欧进行有选择的缓和和经济合作的政策,其部分原因首先是这项政策能给它带来技术和贸易方面的实惠;其次是这样做可能使欧洲人远离美国人;最后是中国在苏联的亚洲战线上向它提出了挑战。然而,从长远来看,一个繁荣的、复苏的、在各方面(军事方面除外,但也可能在这方面变得很强大)可能使苏联黯然失色的欧洲,很难说会符合苏联的最佳利益。

Yet if, in retrospect, the United States was better placed to adjust to the changing patterns of world power, that was not obvious for many years after 1960. In the first place, there was a chronic dislike of “Asian Communism,” with Mao’s China replacing Khrushchev’s Russia as the fomenter of world revolution in the eyes of many Americans. China’s border war of 1962 with India, a country which Washington (like Moscow) wished to woo, confirmed the earlier aggressive image emanating from the clashes over Quemoy and Matsu; and détente between the United States and China was hardly conceivable in the early 1960s, when Mao’s propaganda machine was denouncing the Russians for backing down over Cuba and for signing the limited nuclear-test-ban treaty with the West. Finally, between 1965 and 1968 China was in the convulsions of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which made the country appear chronically unstable as well as even more ideologically abhorrent to administrations in Washington. None of this pointed to “a situation in which much progress towards better relations with the United States was likely. ”167

可是,如果回过头来看,美国在使自己适应世界力量的变化方面处于更为有利的地位,虽然这一点在1960年以后的许多年里并不明显。首先,随着在许多美国人看来,中国已取代赫鲁晓夫的苏联,成为世界革命的煽动者,出现了一种对“亚洲共产主义”的经久的厌恶感。1962年中印的边界战争(同苏联一样,美国也希望向印度“求爱”),加深了先前中国金门和马祖诸岛的冲突给中国造成的战争形象。在20世纪60年代初期,当中国谴责苏联人在古巴问题上的屈服行动和同西方一起签署有限核禁试条约的时候,美国和中国之间实现缓和的可能性几乎不存在。其次,在1965年到1968年期间,中国正处于“文化大革命”时期,这场运动使这个国家长时间地不稳定,在意识形态方面甚至更加仇恨美国政府。所有这一切都意味着不会出现一种中国“有可能在改善同美国的关系方面取得重大进展的形势”。

Above all, of course, the United States in these years was itself increasingly convulsed by the problems emerging from the war in Vietnam. The North Vietnamese, and the Vietcong in the South, appeared to most Americans as but new manifestations of the creeping Asian Communism which had to be forcibly contained before it did even further damage; and since those revolutionary forces were being encouraged and supplied by China and Russia, both of the latter Powers (but perhaps especially the bitterly critical regime in Peking) could only be seen as part of a hostile Marxist coalition lined up against the “free world. ” Indeed, as the Johnson administration escalated its own buildup in Vietnam, decision-makers in Washington frequently worried about how far they could go without provoking the sort of Chinese intervention which had occurred in the Korean War. 168 From the Chinese government’s standpoint, it must have been a matter of earnest debate throughout the 1960s about whether the growing clash with the Soviets to the north was as ominous as the ever-escalating American military and aerial operations to the south. Yet while in fact its own relationship with the ethnically different Vietnamese had traditionally been one of rivalry, and it was deeply suspicious of the amount of military hardware which Russia was giving to Hanoi, these tensions were invisible to most western eyes throughout the period of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

当然,在这些年月里,美国本身也因越南战争引起的问题而处于趋向于动荡不安的状态。对大多数美国人来说,北越人和南方越共的表现只是亚洲共产主义的新迹象,在它进一步发展之前必须有力地加以扼制。的确,随着约翰逊政府增兵越南使战争规模升级,令华盛顿的决策者时常焦虑不安的是:在不致引起曾在朝鲜战争中发生过的那种中国干预的情况下,他们能走多远。从中国政府的角度来看,中国必然在整个20世纪60年代对下述问题进行过认真的讨论:在北方同苏联人的冲突的加剧,是否会像在南方美国的军事行动和空中作战行动不断升级那样?这两者都对中国不利。尽管中国与不同种族的越南人的关系在传统上一直是敌对的,并且它对苏联提供给河内的军事装备的数量深表疑虑,但在肯尼迪和约翰逊政府执政时期,大多数西方人士却没有看到这些紧张迹象。

In so many ways, symbolic as well as practical, it would be difficult to exaggerate the impacts of the lengthy American campaign in Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia upon the international power system—or upon the national psyche of the American people themselves, most of whose perceptions of their country’s role in the world still remain strongly influenced by that conflict, albeit in different ways. The fact that this was a war fought by an “open society”—and made the more open because of revelations like the Pentagon Papers, and by the daily television and press reportage of the carnage and apparent futility of it all; that this was the first war which the United States had unequivocally lost, that it confounded the victorious experiences of the Second World War and destroyed a whole array of reputations, from those of four-star generals to those of “brightest and best” intellectuals; that it coincided with, and in no small measure helped to cause, the fissuring of a consensus in American society about the nation’s goals and priorities, was attended by inflation, unprecedented student protests and inner city disturbances, and was followed in turn by the Watergate crisis, which discredited the presidency itself for a time; that it seemed to many to stand in bitter and ironic contradiction to everything which the Founding Fathers had taught, and made the United States unpopular across most of the globe; and finally that the shamefaced and uncaring treatment of the GIs who came back from Vietnam would produce its own reaction a decade later and thus ensure that the memory of this conflict would continue to prey upon the public consciousness, in war memorials, books, television documentaries, and personal tragedies—all of this meant that the Vietnam War, although far smaller in terms of casualties, impacted upon the American people somewhat as had the First World War upon Europeans. The effects were seen, overwhelmingly, at the personal and psychological levels; more broadly, they were interpreted as a crisis in American civilization and in its constitutional arrangements. As such, they would continue to have significance quite independent of the strategical and Great Power dimensions of this conflict.

人们很难从多方面(不管是从表面上,还是从实际上)全面而深刻地理解美国在越南和东南亚其他地区漫长的军事行动对国际力量体系,或对美国的国民心理所产生的影响——尽管方式不同,大部分美国人对国家在世界上所起作用的看法,仍受这场战争的强烈影响。事实上,这是由一个“开放性的社会”进行的一场战争,而由于五角大楼文件的泄密,电视台和报刊每天对战场情况和琐事的报道,致使这场战争变得更加公开化;这是美国真正意义上被打败了的第一场战争,这场战争否定了它在第二次世界大战中的宝贵经验,毁坏了一系列人士——从四星上将到“最聪明和最优秀”的知识分子——的声誉;这场战争同时推动并且在不小的程度上造成了美国社会在国家目的和利益权衡等方面的一致性的分裂,带来了通货膨胀、史无前例的学生抗议、城市内的骚乱,并随之导致水门事件危机,一段时间内使总统本身失去了人们的信任;这场战争似乎使很多人在对待开国先驱们的教导上处于痛苦的和具有讽刺意味的矛盾之中,使美国在世界大部分地区不受欢迎;最后,从越南回国的美国大兵感到羞惭的面孔和无人关心的境遇在10年后引起了反应,从而使有关这场战争的回忆持续不断地通过战争回忆录、书籍、电视文献片以及个人发生的悲剧等形式冲击着公众的良知。所有这一切事实意味着,越南战争虽然从伤亡数字看小得多,但对美国人民的影响在某种程度上却像第一次世界大战对欧洲人的影响一样严重。人们可以看到美国人民个人和心理方面所受到的巨大影响;从更广泛的意义上看,人们把这些影响说成是美国文明及其法制体系所发生的一场危机。正因如此,这些影响还会继续发生作用,而根本不管这场冲突的战略格局和大国的作用如何。

But the latter aspects are the most important ones for our survey, and require further mention here. To begin with, it provided a useful and sobering reminder that a vast superiority in military hardware and economic productivity will not always and automatically translate into military effectiveness. That does not undermine the thrust of the present book, which has stressed the importance of economics and technology in large-scale, protracted (and usually coalition) wars between the Great Powers when each combatant has been equally committed to victory. Economically, the United States may have been fifty to one hundred times more productive than North Vietnam; militarily, it possessed the firepower to (as some hawks urged) bomb the enemy back into the stone age—indeed, with nuclear weapons, it had the capacity to obliterate Southeast Asia altogether. But this was not a war in which those superiorities could be made properly effective. Fear of domestic opinion, and of world reaction, prevented the use of atomic weapons against a foe who could never be a vital threat to the United States itself. Worries about the American public’s opposition to heavy casualties in a conflict whose legitimacy and efficacy came increasingly under question had similarly constrained the administration’s use of the conventional methods of warfare; restrictions were placed on the bombing campaign; the Ho Chi Minh Trail through neutral Laos could not be occupied; Russian vessels bearing arms to Haiphong harbor could not be seized. It was important not to provoke the two major Communist states into joining the war. This essentially reduced the fighting to a series of small-scale encounters in jungles and paddy fields, terrain which blunted the advantages of American firepower and (helicopter-borne) mobility, and instead placed an emphasis upon jungle-warfare techniques and unit cohesion—which was much less of a problem for the crack forces than for the rapidly turning over contingents of draftees. Although Johnson followed Kennedy’s lead in sending more and more troops to Vietnam (it peaked at 542,000, in 1969), it was never enough to meet General Westmoreland’s demands; clinging to the view that this was still a limited conflict, the government refused to mobilize the reserves, or indeed to put the economy on a war footing. 169

后面提到的这两个方面是我们研究的最重要的问题,需要做进一步的讨论。我们先从下面一点谈起:这场战争对我们来说是一服有益的、使人清醒的清凉剂。它提醒我们,军事装备和经济生产力的巨大优势,并不经常自动地转化为军事效能。这一点并不损害本书的主线,这条主线强调的是,在大规模的、持久的大国(并且通常是联盟)间的战争中,在交战各方都平等地投入全力争取胜利的情况下,经济和技术起着重要作用。从经济上看,美国在生产力方面拥有的优势可能是北越的50~100倍;从军事上看,美国方面拥有的火力(就像某些鹰派分子所说的)能够把敌人炸回到石器时代——的确,它可以使用核武器把东南亚整个抹掉。但是,这不是一场让这些方面的优势能够充分发挥效能的战争。美国由于害怕国内舆论和世界反应,而不敢对从来就不可能对美国本身造成重大威胁的敌人使用原子武器。美国担心在一场合法性和效力都越来越成问题的战争中遭受严重伤亡,从而引起美国公众的反对。这种担心同样对美国政府的常规作战方法的运用起到了制约作用,使美国对空中轰炸活动做出了限制;不能占领通过中立的老挝的“胡志明小道”;不能夺取载运武器开往海防港的苏联船只。重要的是,不能促使那两个主要的社会主义国家参加这场战争。这一切实质上把这场战争降低为一系列的小规模丛林和稻田战,而在这类地形上,美军的火力和直升机空降机动力优势发挥不出来;相反,美军不得不强调丛林战技术和部队凝聚力,这两点对于精锐部队来说并不是什么问题,但对匆忙征兵组建的部队来说,却不尽然了。虽然约翰逊追随肯尼迪向越南一再增兵(1969年最高峰时曾达54.2万人),但从未满足威斯特摩兰将军的需要;美国政府坚持认为这只是一场有限冲突,拒绝征召预备役部队参战,也从未使经济转入战时轨道。

The difficulties of fighting the war on terms disadvantageous to the United States’ real military strengths reflected a larger political problem—the discrepancy between means and ends (as Clausewitz might have put it). The North Vietnamese and the Vietcong were fighting for what they believed in very strongly; those who were not were undoubtedly subject to the discipline of a totalitarian, passionately nationalistic regime. The South Vietnamese governing system, by contrast, appeared corrupt, unpopular, and in a distinct minority, opposed by the Buddhist monks, unsupported by a frightened, exploited, and warweary peasantry; those native units loyal to the regime and who often fought well were not sufficient to compensate for this inner corrosion. As the war escalated, more and more Americans questioned the efficacy of fighting for the regime in Saigon, and worried at the way in which all this was corrupting the American armed forces themselves—in the decline in morale, the rise in cynicism, indiscipline, drug-taking, prostitution, the increasing racial sneers at the “gooks,” and atrocities in the field, not to mention the corrosion of the United States’ own currency or of its larger strategic posture. Ho Chi Minh had declared that his forces were willing to lose men at the rate of ten to one—and when they were rash enough to emerge from the jungles to attack the cities, as in the 1968 Tet offensive, they often did; but, he continued, despite those losses they would still fight on. That sort of willpower was not evident in South Vietnam. Nor was American society itself, increasingly disturbed by the war’s contradictions, willing to sacrifice everything for victory. While the latter feeling was quite understandable, given what was at stake for each side, the fact was that it proved impossible for an open democracy to wage a halfhearted war successfully. This was the fundamental contradiction, which neither McNamara’s systems analysis nor the B-52 bombers based on Guam could alter. 170

在对美国实际的军事实力不利的条件下打仗的困难,反映了一个更大的政治问题——(正如克劳塞维茨所指出的)手段和目的之间的不适应。北越人和越共为他们强烈信仰的事业而战,没有这种信仰的人无疑也受到极权的、强烈的民族主义政权的纪律约束。相比之下,南越的政府体系则充满腐败现象,不受人们欢迎,处于明显的少数,遭到佛教僧侣们的反对,得不到惊恐不安的、被剥削的、厌倦战争的农民的支持;忠于政府的本地部队和能征善战的部队不足以抵消这种内部的衰败。随着战争的升级,越来越多的美国人对为西贡政府进行的这场战争的价值提出了怀疑,并对腐蚀美国武装部队本身的一切表现——士气低落、不信任感的增长、无纪律现象、吸毒、纵淫现象、对土著人的种族歧视、战地的暴行(更不用说美国本身的整个形势或其更大范围内的战略态势的恶化)——表示忧虑不安。胡志明曾经宣布,他的军队甘愿以10比1的比例牺牲。当他的部队十分轻率地由丛林中走出来进攻城市时(像1968年的春季攻势那样),他们常常会有这么大的牺牲。但是,胡志明说,纵然遭到这么大的损失,他们仍会继续战斗下去。这种意志力在南越方面是看不到的。美国社会本身也没有这种意志力;它日益被战争的矛盾所困扰,不愿意付出一切牺牲去争取胜利。尽管后者的感情是完全可以理解的,但假定这一点对双方都至关重要,那么事实是(并且现实已经证明),开放的民主国家不可能成功地进行一场半心半意的战争。这就是这场战争的基本矛盾,不论是麦克纳马拉的系统分析,还是驻在关岛的B-52轰炸机,都不可能改变这一点。

More than a decade after the fall of Saigon (April 1975), and with books upon all aspects of that conflict still flooding from the presses, it still remains difficult to assess clearly how it may have affected the U. S. position in the world. Viewed from a longer perspective, say, backward from the year 2000 or 2020, it might be seen as having produced a salutory shock to American global hubris (or to what Senator Fulbright called “the arrogance of power”), and thus compelled the country to think more deeply about its political and strategical priorities and to readjust more sensibly to a world already much changed since 1945—in other words, rather like the shock which the Russians received in the Crimean War, or the British received in the Boer War, producing in their turn beneficial reforms and reassessments.

在1975年4月西贡陷落后的10多年里,出版社仍在大量出版论述那场战争的各个方面的书籍,人们仍然难以明确地估计出那场战争对美国在世界上的地位到底有怎样的影响。在未来——例如从2000年或2020年回头看,人们可能发现,这场冲突对美国全球性的过分骄傲(或如参议员富布赖特所谓的“力量上的傲慢”)产生了一种有益的震撼,从而迫使这个国家更加深入地思考自己政治和战略上的利弊得失,更加明智地重新做出调整,使自己适应1945年以来早已发生巨大变化的世界形势。换言之,这一震撼很像俄国人在克里米亚战争中或英国人在布尔战争中受到的震撼,它们因此进行了有益的改革并做出重新估计。

At the time, however, the short-term effects of the war could not be other than deleterious. The vast boom in spending on the war, precisely at a time when domestic expenditures upon Johnson’s “Great Society” were also leaping upward, badly affected the American economy in ways which will be examined below (pp. 434–35). Moreover, while the United States was pouring money into Vietnam, the USSR was devoting steadily larger sums to its nuclear forces—so that it achieved a rough strategic parity—and to its navy, which in these years emerged as a major force in global gunboat diplomacy; and this increasing imbalance was worsened by the American electorate’s turn against military expenditures for most of the 1970s. In 1978, “national security expenditures” were only 5 percent of GNP, lower than they had been for thirty years. 171 Morale in the armed services plummeted, in consequence both of the war itself and of the postwar cuts. Shakeups in the CIA and other agencies, however necessary to check abuses, undoubtedly cramped their effectiveness. The American concentration upon Vietnam worried even sympathetic allies; its methods of fighting in support of a corrupt regime alienated public opinion, in western Europe as much as in the Third World, and was a major factor in what some writers have termed American “estrangement” from much of the rest of the planet. 172 It led to a neglect of American attention toward Latin America— and a tendency to replace Kennedy’s hoped-for “Alliance for Progress” with military support for undemocratic regimes and with counterrevolutionary actions (like the 1965 intervention in the Dominican Republic). The—inevitably—open post-Vietnam War debate over the regions of the globe for which the United States would or would not fight in the future disturbed existing allies, doubtless encouraged its foes, and caused wobbling neutrals to consider re-insuring themselves with the other side. At the United Nations debates, the American delegate appeared increasingly beleaguered and isolated. Things had come a long way since Henry Luce’s assertion that the United States would be the elder brother of nations in the brotherhood of man. 173

然而,现时也不能对这场战争的近期影响视而不见。正当拨给约翰逊建设“伟大社会”用的国内开支直线上升的时候,战争开支的大量增加对美国的经济产生了严重的不良影响,具体情况后面还将讨论。而且,在美国把大量金钱投入越南战争的时候,苏联却在稳步地拿出更多的钱来扩充它的核部队(这样,它就取得了大体上的战略均势)和海军。在这些年里,它的海军已成为一支执行全球性炮舰外交的主要力量。在20世纪70年代的大部分时间里,美国选民转而反对增加军费开支,使这种日趋严重的不平衡进一步恶化了。在1978年,美国“国家安全开支”仅占国民生产总值的5%,低于30年来一直保持的数字。由于战争本身和此次战争后的削减所产生的后果,武装部队的士气一落千丈。美国中央情报局和其他机构的大改组,尽管是消除弊端所必要的,但无疑降低了它们的效能。美国把主要精力集中在越南,甚至使同情美国的盟国也感到忧虑;美国为了支持一个腐败政权的作战方式,疏远了西欧以及在更大程度上第三世界的公众舆论,并因此“疏远”了这个星球上其余的大多数人,就像某些作者所说的那样。这导致美国忽视拉丁美洲并产生一种倾向:以对不民主的政权的军事支援和反对革命的行动(如1965年对多米尼加共和国的干涉),来代替肯尼迪所希望的“进步联盟”。越南战争之后所发生的那场不可避免的、公开化的、关于美国是否在将来应为全球一些地区而战的大辩论,引起了现有盟国的不安,无疑也鼓励了美国的敌人,并促使动摇不定的中立国与另一方联合起来,以重新确保自己的安全。在联合国的大会辩论中,美国代表越来越受到围攻并变得孤立。自从亨利·鲁斯断言在人类兄弟般的友谊中美国将是各国的老大哥以来,事情已经有了很大的变化。

The other power-political consequence of the Vietnam War was that it obscured, by perhaps as much as a decade, Washington’s recognition of the extent of the Sino- Soviet split—and thus its chance to evolve a policy to handle it. It was therefore the more striking that this neglect should be put right so swiftly after the entry into the presidency of that bitter foe of Communism Richard Nixon, in January 1969. But Nixon possessed, to use Professor Gaddis’s phrase, a “unique combination of ideological rigidity with political pragmatism”174—and the latter was especially manifest in his dealings with foreign Great Powers. Despite Nixon’s dislike of domestic radicals and animosity toward, say, Allende’s Chile for its socialist policies, the president claimed to be unideological when it came to global diplomacy. To him, there was no great contradiction between ordering a massive increase in the bombing of North Vietnam in 1972—to compel Hanoi to come closer to the American bargaining position for withdrawal from the South—and journeying to China to bury the hatchet with Mao Tse-tung in the same year. Even more significant was to be his choice of Henry Kissinger as his national security adviser (and later secretary of state). Kissinger’s approach to world affairs was historicist and relativistic: events had to be seen in their larger context, and related to each other; Great Powers should be judged on what they did, not on their domestic ideology; an absolutist search for security was Utopian, since that would make everyone else absolutely insecure—all that one could hope to achieve was relative security, based upon a reasonable balance of forces in world affairs, a mature recognition that the world scene would never be completely harmonious, and a willingness to bargain. Like the statesmen he had written about (Metternich, Castlereagh, Bismarck), Kissinger felt that “the beginning of wisdom in human as well as international affairs was knowing when to stop. ”175 His aphorisms were Palmerstonian (“We have no permanent enemies”) and Bismarckian (“The hostility between China and the Soviet Union served our purposes best if we maintained closer relations with each side than they did with each other”),176 and were unlike anything in American diplomacy since Kennan. But Kissinger had a much greater chance to direct policy than his fellow admirer of nineteenth-century European statesmen ever possessed. 177

越南战争导致的另一个强权政治后果是,它使美国可能在长达10年的时间内搞不清中苏分裂的程度,从而失去了采取应对政策的机会。而更引人注目的是,这一忽视在1969年1月尼克松就任总统之后竟能迅速地改正过来。可是,用加迪斯教授的话说,尼克松具有一种“独特的思想上的僵硬与政治上的实用主义相结合的品质”,而其政治上的实用主义在他同其他大国打交道时表现得尤其突出。尽管尼克松厌恶国内的激进主张,对(例如)智利所采取的社会主义政策持敌对态度,但据说尼克松在处理全球外交问题时却并不受意识形态的支配。对他来说,1972年下令大规模增加对北越的轰炸,以迫使北越更接近美国为撤出南越而采取的讨价还价的立场,和同年到中国走一趟,同毛泽东一起填平鸿沟,并没有什么大的矛盾。更具重要意义的是,他选用亨利·基辛格做他的国家安全事务助理(后来又任国务卿)。基辛格采取历史主义和相对主义的态度处理世界事务:强调从更大范围观察事物,把一切事物互相联系起来进行考察;判断大国应根据其所作所为,而不应根据其国内的意识形态;用绝对主义观点观察安全问题是乌托邦式的幻想,因为那种做法不会使任何人感到绝对安全——人们能够指望获得的只是建立在世界事务中合理的力量对比基础上的相对安全;老老实实地承认整个世界永远不会达到完全的和谐一致,并且要有同其他国家打交道的愿望。同他所描述过的政治家(梅特涅、卡斯尔雷子爵,俾斯麦)[5]一样,基辛格认识到了“知道何时适可而止,乃是运用智慧处理人类和国家事务的开端”这一真谛。他的格言是巴麦尊[6]式的(“我们没有永久的敌人”)和俾斯麦式的(“如果我们与中苏双方保持比它们之间更为密切的关系,则中苏之间的敌对最有利于我们的目的”),并且与凯南[7]以来美国外交中实行的信条没有任何相似之处。但是,基辛格比他19世纪欧洲政治家中受尊敬的同人们拥有大得多的机会去指导政策的实践。

Finally, Kissinger recognized the limitations upon American power, not only in the sense that the United States could not afford to fight a protracted war in the jungles of Southeast Asia and to maintain its other, more vital interests, but also because both he and Nixon could perceive that the world’s balances were altering, and new forces were undermining the hitherto unchallenged domination of the two superpowers. The latter were still far ahead in terms of strictly military power, but in other respects the world had become more of a multipolar place: “In economic terms,” he noted in 1973, “there are at least five major groupings. Politically, many more centers of influence have emerged. …” With echoes of (and amendments to) Kennan, he identified five important regions, the United States, the USSR, China, Japan, and western Europe; and unlike many in Washington and (perhaps) everyone in Moscow, he welcomed this change. A concert of large powers, balancing each other off and with no one dominating another, would be “a safer world and a better world” than a bipolar situation in which “a gain for one side appears as an absolute loss for the other. ”178 Confident in his own abilities to defend American interests in such a pluralistic world, Kissinger was urging a fundamental reshaping of American diplomacy in the largest sense of that word.

此外,基辛格承认美国力量的局限性,这不仅表现在美国无力在东南亚的丛林地中打一场持久战争和保卫它的其他更加重要的利益上,而且还表现在他和尼克松都能洞察世界力量对比格局正在发生变化,新的力量正在破坏两个超级大国还未遇到挑战的霸权。从严格的军事意义来看,后面这种情况还远远未成气候,但在其他方面,世界已变得更加多极化。他在1973年指出:“在经济方面,至少已出现5个主要集团。从政治上看,更多的势力中心已经出现……”由于附和凯南的观点(加上他自己的修正补充),基辛格指出了5个重要的地区:美国、苏联、中国、日本和西欧。不像华盛顿的许多人士和(可能)莫斯科的那些人士,他欢迎这种变化。大国实现和谐,互有节制,任何一国都不想控制他国,可以创造“一个比在两极情况下更安全、更美好的世界”,而在两极并存的情况下,“一方所得必然是另一方的绝对所失”。基辛格怀着对他个人在这样一个多极世界中保卫美国利益的能力的信心,在最大意义上彻底重塑了美国的外交。

The diplomatic revolution caused by the steady Sino-American rapprochement after 1971 had a profound effect on the “global correlation of forces. ” Although taken by surprise at Washington’s move, Japan felt that it at last was able to establish relations with the People’s Republic of China, which thus gave a further boost to its booming Asian trade. The Cold War in Asia, it appeared, was over—or perhaps it would be better to say that it had become more complicated: Pakistan, which had been a diplomatic conduit for secret messages between Washington and Peking, received the support of both those Powers during its clash with India in 1971; Moscow, predictably, gave strong support to New Delhi. In Europe, too, the balances had been altered. Alarmed by China’s hostility and taken aback by Kissinger’s diplomacy, the Kremlin deemed it prudent to conclude the SALT I treaty and to encourage the various other attempts to improve relations across the Iron Curtain. It also held back when, following its tense confrontation with the United States at the time of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, Kissinger commenced his “shuttle diplomacy” to reconcile Egypt and Israel, effectively freezing Russia out of any meaningful role.

1971年后中美友好关系的稳步恢复所引起的这场外交革命,对“全球的力量关系格局”发生了深远的影响。日本虽然对华盛顿的这一步棋感到意外,但它感到终于能够同中华人民共和国建立外交关系了,而这种关系又进一步推动了它那欣欣向荣的亚洲贸易。当时的情况是,亚洲的“冷战”表面上结束了,但更确切地说,事情变得更加复杂了:曾经充当中国和美国之间秘密交流信息的外交渠道的巴基斯坦,在1971年同印度发生冲突期间同时接受这两个国家的援助;据估计,苏联也向印度提供了强大的支援。在欧洲,力量对比格局也发生了变化。由于对中国的敌对和对基辛格外交感到震惊,克里姆林宫认为,缔结限制战略武器会谈第一阶段条约和鼓励采取其他各种方式改善同“铁幕”以外国家的关系,是明智的。在1973年阿以战争中,美苏进行了紧张的对抗之后,由基辛格开始进行“穿梭外交”来缓和埃及与以色列的关系,以便有效地冻结苏联可能起到的任何有意义的作用。在这个时候,苏联人也采取了克制的态度。

It is difficult to know how long Kissinger could have kept up his Bismarck-style juggling act had the Watergate scandal not swept Nixon from the White House in August 1974 and made so many Americans even more suspicious of their government. As it was, the secretary of state remained in his post during Ford’s tenure of the presidency, but with increasingly less freedom for maneuver. Defense budget requisitions were frequently slashed by Congress. All further aid was cut off to South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in February 1975, a few months before those states were overrun. The War Powers Act sharply pared the president’s capacity to commit American troops overseas. Soviet-Cuban interventions in Angola could not, Congress had voted, be countered by sending CIA funds and weapons to the prowestern factions there. With the Republican right growing restive at this decline in American power abroad and blaming Kissinger for ceding away national interests (the Panama Canal) and old friends (Taiwan), the secretary of state’s position was beginning to crumble even before Ford was swept out of power in the 1976 election.

如果水门事件没有在1974年8月把尼克松赶出白宫,使许多美国人更加怀疑自己的政府,很难说基辛格“俾斯麦式”的外交戏法能够持续多久。尽管如此,这位国务卿在福特总统任期内一直留在自己的岗位上,但机动处事的自由却越来越少了。美国国会经常削减所申请的国防预算。在南越、柬埔寨和老挝被倾覆的前几个月,即在1975年2月,美国国会削减了对这些国家全部的新援助。《战争权力法案》急剧削减了总统在海外用兵的权力。美国国会投票通过了以下决议:对于苏联和古巴在安哥拉的干涉行动,美国只能以通过中央情报局向那里的亲西方派别提供资金和武器的方式来对付。随着共和党右翼对美国在海外实力的下降日益不安,对基辛格放弃美国的国家利益(巴拿马运河)和老朋友(中国台湾)的不满情绪的增长,使这位国务卿的地位在1976年大选中福特失去其权力之前,就开始下降了。

As the United States grappled with serious socioeconomic problems throughout the 1970s and as different political groups tried to reconcile themselves to its reduced international position, it was perhaps inevitable that its external policies would be more erratic than was the case in placid times. Nonetheless, there were to be “swings” in policy over the next few years which were remarkable by any standards. Imbued with the most creditable of Gladstonian and Wilsonian beliefs about the need to create a “fairer” global order, Carter breezily entered an international system in which many of the other actors (especially in the world’s “trouble spots”) had no intention of conducting their policies according to Judeo- Christian principles. Given the Third World’s discontent at the economic gap between rich and poor nations, which had been exacerbated by the 1973 oil crisis, there was prudence as well as magnanimity in his push for north-south cooperation, just as there was common sense in the terms of the renegotiated Panama Canal treaty, and in his refusal to equate every Latin American reformist movement with Marxism. Carter also took justified credit for “brokering” the 1978 Camp David agreement between Egypt and Israel—although he ought not to have been so surprised at the critical reaction of the other Arab nations, which in turn was to give Russia the opportunity to strengthen its ties with the more radical states in the Middle East. For all its worthy intentions, however, the Carter government foundered upon the rocks of a complex world which seemed increasingly unwilling to abide by American advice, and upon its own inconsistencies of policy (often caused by quarrels within the administration). 179 Authoritarian, right-wing regimes were berated and pressured across the globe for their human-rights violations, yet Washington continued to support President Mobutu of Zaire, King Hassan of Morocco, and the shah of Iran—at least until the latter’s demise in 1979, which led to the hostages crisis, and in turn to the flawed attempt to rescue them. 180 In other parts of the globe, from Nicaragua to Angola, the administration found it difficult to discover democratic-liberal forces worthy of its support, yet hesitated to commit itself against Marxist revolutionaries. Carter also hoped to keep defense expenditures low, and appeared bewildered that détente with the USSR had halted neither that country’s arms spending nor its actions in the Third World. When Russian troops invaded Afghanistan at the end of 1979, Washington, which was by then engaged in a large-scale defense buildup, withdrew the SALT II treaty, canceled grain sales to Moscow, and began to pursue—especially in Brzezinski’s celebrated visits to China and Afghanistan—“balance-of-power” politics which the president had condemned only four years earlier. 181

由于美国在整个20世纪70年代面临着严重的社会经济问题,以及不同的政治集团试图使自己适应美国国际地位的下降,下述情况就不可避免地出现了:它们的对外政策比起平静时代来更加反复无常。就是这样,在之后几年里还将发生以任何标准来衡量都令人注目的政策上的“摇摆”。受格莱斯顿和威尔逊[8]的最可信赖的关于必须建立“更加公正的”全球秩序这一信仰的影响,卡特轻松地进入了一种国际体系,在这个体系中,其他许多角色(尤其是在世界的“麻烦地点”)都无意按照犹太教与基督教共有的原则推行他们的政策。鉴于第三世界对富国和穷国之间的经济差距——这个差距又因1973年石油危机而进一步扩大——深表不满,他采取了一种明智的、慷慨的态度来推动南北合作;同样,他在重启《巴拿马运河条约》谈判的条件方面,以及拒绝平等对待拉丁美洲每个带有马克思主义性质的改革运动方面,都表现出他的常识。卡特还光荣地受委托充当了1978年埃以《戴维营协议》的“经纪人”——尽管他不应当对其他阿拉伯国家的尖锐反应感到奇怪,但反过来这种情况却使苏联得到了一个机会来加强其同中东更激进的国家的联系。然而,纵然卡特政府怀有一切有价值的打算,这个政府却是建立在一个复杂的世界(越来越不愿听任美国摆布的世界)及其本身政策前后不一致(这些不一致往往是由政府内部的争吵造成)的基础之上的。全世界都谴责践踏人权的独裁的右翼政权,并对它们施加压力,可是华盛顿却继续支持扎伊尔总统蒙博托、摩洛哥国王哈桑和伊朗的国王——对后者的支持至少到其1979年任满为止,这样又导致了人质危机以及徒劳无功的解救人质的行动。在世界其他地区,从尼加拉瓜到安哥拉,美国政府难以找到值得它支持的民主自由力量,可是对于使自己投身到反对马克思主义革命的行动之中,又踌躇不决。卡特希望保持防务开支的低水平,却表现出迷惑混乱,他认为同苏联缓和关系既不能停止那个国家的军备开支,也不能制止它在第三世界所采取的行动。当苏军在1979年底入侵阿富汗时,正在大规模扩充防务的华盛顿退出了限制战略武器谈判第二阶段条约,取消了向苏联出售粮食的计划,并开始推行(尤其是在布热津斯基对中国和阿富汗进行值得庆贺的访问之际)“均势”政策,而仅4年前这位总统还在谴责这一政策!

If the Carter administration had come into office with a set of simple recipes for a complex world, those of his successor in 1980 were no less simple—albeit drastically different. Suffused by an emotional reaction against all that had “gone wrong” with the United States over the preceding two decades, boosted by an electoral landslide much affected by the humiliation in Iran, charged by an ideological view of the world which at times seemed positively Manichaean, the Reagan government was intent upon steering the ship of state in quite new directions. Détente was out, since it merely provided a mask for Russian expansionism. The arms buildup would be increased, in all directions. Human rights were off the agenda; “authoritarian governments” were in favor. Amazingly, even the “China card” was suspect, because of the Republican right’s support for Taiwan. As might have been expected, much of this simplemindedness also foundered on the complex realities of the world outside, not to mention the resistance of a Congress and public which liked their president’s homely patriotism but suspected his Cold War policies. Interventions in Latin America, or in any place clad in jungles and thus reminiscent of Vietnam, were constantly blocked. The escalation of the nuclear arms race produced widespread unease, and pressure for renewed arms talks, especially when administration supporters talked of being able to “prevail” in a nuclear confrontation with the Soviet Union. Authoritarian regimes in the tropics collapsed, often made more unpopular by association with the American government. The Europeans were bewildered at a logic which forbade them to buy natural gas from the USSR, but permitted American farmers to sell that country grain. In the Middle East, the Reagan administration’s inability to put pressure upon Mr. Begin’s Israel contradicted its strategy of lining up the Arab world in an anti-Russian front. At the United Nations, the United States seemed more isolated than ever; by 1984, it had withdrawn from UNESCO—a situation which would have amazed Franklin Roosevelt. By more than doubling the defense budget in five years, the United States was certainly going to possess greater military hardware than it did in 1980; but whether the Pentagon was receiving good value for its outpourings was increasingly doubted, as was the question of whether it could control its interservice rivalries. 182 The invasion of Grenada, trumpeted as a great success, was in various operational aspects worryingly close to a Gilbert and Sullivan farce. Last but not least, even sympathetic observers wondered if this administration could work out a coherent grand strategy when so many of its members were quarreling with one another (even after Haig’s retirement as secretary of state), when its chief appeared to give little attention to critical issues, and when (with rare exceptions) it viewed the world outside through such ethnocentric spectacles. 183

如果说卡特上台时已有一套应付一个复杂世界的简单“处方”,那么可以说1980年他的继任者的“处方”也同样简单,只不过大不相同罢了。里根政府满怀着人们对美国在前20年中所犯一切“过失”的强烈反应,在大选中获得的压倒优势——这在很大程度上受到了在伊朗蒙受耻辱的影响,并在此推动之下,带着一种从意识形态角度观察世界的态度(这种观察不时地表现为积极的摩尼教性质的),打算操纵国家航船驶往一个完全不同的新方向。它不再提“缓和”了,因为这只能为苏联人的扩张主义提供一个假面具。它将全方位加强军备建设。议事日程上不再提人权,“独裁政府”受到了它的青睐。令人惊异的是,甚至“中国牌”也因共和党右翼支持“中国台湾”而不可信了。正如人们可以预料的那样,这种头脑简单的想法在很大程度上也是建立在外部世界复杂现实的基础上的,更不用说国会和公众的反抗了。国会和公众喜欢总统在国内的爱国主义,但怀疑他的“冷战”政策。对拉丁美洲的干涉,或者到任何地方从事丛林战(使人们回忆起越南)都经常受到禁止。核军备竞赛的升级引起了普遍的不安,因而要求重开裁军会谈的压力很大,尤其是在政府的支持者认为美国能在同苏联的核对抗中“取胜”的时候,这种压力就更大。热带地区垮台的独裁政权常常因同美国政府有牵连而更加不受欢迎。欧洲人对这样一种逻辑迷惑不解:一方面禁止他们向苏联购买天然气,另一方面又允许美国的农场主向苏联出售农产品。在中东,里根政府无力向贝京领导的以色列施加压力,这同它把阿拉伯世界团结起来建成一条反苏阵线的战略发生了矛盾。在联合国,美国似乎比以往更加孤立。到1984年,它已从联合国教科文组织中退出,这一做法必然会使富兰克林·罗斯福感到吃惊。由于在5年内使国防预算增加了一倍以上,美国肯定要比1980年拥有更多的军事装备。但是,人们越来越怀疑五角大楼是否因为自己的努力而受到好评,它是否能够控制各军种间的竞争。对格林纳达的入侵被自吹自擂地说成是一个伟大的胜利,但从作战的各方面来衡量,几乎像一出吉尔伯特与沙利文喜剧一样令人不安。最后(当然远不只此),甚至具有同情感的观察家们也怀疑,本届政府是否能够在下述情况下搞出一项协调一致的大战略来:在政府成员中,有好多人互相争吵不休,甚至在国务卿黑格从这一岗位上退休之后也是如此;政府首脑表现得很少关心紧迫的问题;政府往往戴着民族优越感的眼镜来观察外部世界(例外的情况很少)。

Many of these issues will be returned to in the final chapter. The point about listing the various troubles of the Carter and Reagan administrations together was that they had, taken as a whole, distracted attention from the larger forces which were shaping global power politics—and most particularly that shift from a bipolar to a multipolar world which Kissinger had much earlier detected and begun to adjust to. (As will be seen below, the emergence of three additional centers of political-cum-economic power—western Europe, China, and Japan—did not mean that the latter were free of problems either; but that is not the point here. ) More important still, the American concentration upon the burgeoning problems of Nicaragua, Iran, Angola, Libya, and so on was still tending to obscure the fact that the country most affected by the transformations which were occurring in global politics during the 1970s was probably the USSR itself—a consideration which deserves some further brief elaboration before this section concludes.

在上述问题中,有许多问题还要在本书最后一章中谈到。我们在这里把卡特和里根政府的各种各样的难题归纳在一起,目的在于指出:从整体来看,它们已经转移了对正在形成全球强权政治格局的更大力量的注意力;最为重要的是,两极世界已转化为多极世界,这一点基辛格很早就发现了,并着手进行了调整。(下面还将看到,三个新的政治兼经济力量中心——西欧、中国和日本——的出现,并不意味着它们没有自己的问题,但与这里所讨论的无关。)更加重要的是,美国把自己的精力集中在尼加拉瓜、伊朗、安哥拉、利比亚等国突然出现的问题上,倾向于使人们看不清以下事实:受20世纪70年代全球政治格局变化影响最大的国家,可能是苏联本身。在本节结束之前,有必要对这一点进一步做些简要的分析。

That the USSR had enhanced its military strength in these years was undoubted. Yet, as Professor Ulam points out, because of other developments, that simply meant that the rulers of the Soviet Union were in a position to appreciate the uncomfortable discovery made by so many Americans in the forties and fifties: enhanced power does not automatically, especially in the nuclear age, give a state greater security. From almost every point of view, economically and militarily, in absolute and in relative terms, the USSR under Brezhnev was much more powerful than it had been under Stalin. And yet along with this greatly increased strength came new international developments and foreign commitments that made the Soviet state more vulnerable to external danger and the turbulence of world politics than it had been, say, in 1952. 184

在这些年里,苏联已加强了自己的军事实力,这是毫无疑问的。但是,正如乌拉姆教授所指出的,由于其他事态的发展,这一点仅意味着: 苏联的统治者现在能够理解很多美国人在20世纪40年代和50年代的痛苦发现:力量的增强并不会自动地(尤其是在核时代)使一个国家获得更大的安全。从几乎各种观点——不管是从经济上、军事上,还是从绝对意义、相对意义上——看,勃列日涅夫领导下的苏联比斯大林领导下的苏联要强大得多。可是,随着它的实力大大加强,也出现了新的国际事态,提出了新的对外义务,这使苏联比以往,比方说比1952年,更容易受外部危险和世界政治的动荡不安的影响。

Moreover, even in the closing years of the Carter administration the United States had resumed a defense buildup which—continued at a massive pace by the succeeding Reagan government—threatened to restore U. S. military superiority in strategic nuclear weaponry, to enhance U. S. maritime supremacy, and to place a heavier emphasis than ever before upon advanced technology. The annoyed Soviet reply that they would not be outspent or outgunned could not disguise the awkward fact that this would place increased pressure upon an economy which had significantly slowed down (pp. 429–32 below) and was not well positioned to indulge in a high-technology race. 185 By the late 1970s, it was in the embarrassing position of needing to import large amounts of foreign grain, not to mention technology. Its satellite empire in eastern Europe was, apart from the select Communist party cadres, increasingly disaffected; the Polish discontents in particular were a dreadful problem, and yet a repetition of the 1968 Czech invasion seemed to promise little relief. Far to the south, the threat of losing its Afghan buffer state to foreign (probably Chinese) influences provoked the 1979 coup d’état, which not only turned out to be a military quagmire but had a disastrous impact upon the Soviet Union’s standing abroad. 186 Russian actions in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Afghanistan had much reduced its appeal as a “model” to others, whether in western Europe or in Africa. Muslim fundamentalism in the Middle East was a disturbing phenomenon, which threatened (as in Iran) to vent itself against local Communists as well as against pro-American groupings. Above all, there was the relentless Chinese hostility, which, thanks to the Afghan and Vietnam complications, seemed even more marked at the end of the 1970s than it had at the beginning. 187 If any of the two superpowers had “lost China,” it was Russia. Finally, the ethnocentricity and narrow suspiciousness of its aging rulers and the obstructiveness of its domestic elites, the nomenklatura, toward sweeping reforms were probably going to make a successful adjustment to the newer world balances even more difficult than for the United States.

而且,甚至在卡特政府任期行将结束的那几年,美国就恢复了扩充防务的工作。这项工作在继任的里根政府的领导下,继续以很高的速度进行着,大有恢复美国在战略核武器方面的军事优势、加强美国的海上霸权和比以往更加强调先进技术之势。陷入苦恼的苏联人的回答——他们在军费开支和置办武器方面绝不能落在后面——并不能掩饰这一难堪事实:这样做会对他们的经济造成更大的压力(他们的经济发展速度已大大减慢),并会使他们在高技术竞赛中处于不利地位。到20世纪70年代末期,苏联便处于需要进口大量外国粮食的窘迫处境,更不用说技术了。它的东欧卫星国,除了经过挑选的共产党干部以外,越来越对它不满;波兰人的不满尤其可怕,而重搞1968年入侵捷克斯洛伐克那种行动,似乎也无济于事。在南方,由于担心它的缓冲国阿富汗落入外国势力(可能是中国势力)之手,苏联在1979年搞了武装政变。结果,它不仅变成了苏联军事上的一个泥潭,而且对苏联在国外的处境产生了灾难性的影响。苏联在捷、波、阿的行动,大大减弱了苏联作为其他国家(不管是西欧的,还是非洲的国家)的“模式”的吸引力。中东地区的伊斯兰宗教激进主义是一种不安定的因素,像在伊朗一样,它既反对当地共产党人,也反对亲美集团。不仅如此,还有中国的无情的敌对态度,这种敌对态度由于阿富汗和越南的纠纷,在20世纪70年代末似乎变得比70年代初期还显著。如果说两个超级大国中哪一个已“失去了中国”,那便是苏联。最后,苏联年事已高的统治者所具有的那种民族优越感和狭隘的怀疑心,以及国内的精英——权力集团——对涉及一切领域的改革所起的障碍作用,同美国的情况比较起来,有可能使苏联更加难以成功地做出调整,以使自己适应新的世界力量对比格局。

All this ought to have been of some consolation in Washington, and acted as a guide to a more relaxed and sophisticated view of foreign-policy problems, even when the latter were unexpected and unpleasant. On some issues, admittedly, such as modifying earlier support for Taiwan, the Reagan administration did become more pragmatic and conciliatory. Yet the language of the 1979–1980 election campaign was difficult to shake off, perhaps because it had not been mere rhetoric, but a fundamentalist view of the world order and of the United States’ destined place in it. As had happened so often in the past, the holding of such sentiments always made it difficult for countries to deal with external affairs as they really were, rather than as they thought they should be.

上述这一切应当能使美国获得某种安慰,并成为引导美国对外交政策采取更松动和更缜密的看法的指南,甚至当外交政策遇到意料不到的、令人不愉快的问题时,也是如此。应当承认,在某些问题上,如改变以前对中国台湾的支持,里根政府更多的是从实用主义和和解的立场出发的。可是,他很难摆脱自己在1979~1980年大选期间所说的话,这可能是因为这些话并不只是浮夸之词,而是对世界秩序和对美国注定在其中的地位的一种基本看法。就像过去经常发生的一样,任何国家要是充满这类情绪,它们就总是难以按照事物的本来面目去处理外部事务;相反,它们必定会按照自己的主观想法去干。