The Changing Economic Balances, 1950 to 1980

变化中的经济格局(1950~1980)

In July 1971, Richard Nixon repeated his opinion to a group of news-media executives in Kansas City that there now existed five clusters of world economic power—western Europe, Japan, and China as well as the USSR and the United States. “These are the five that will determine the economic future and, because economic power will be the key to other kinds of power, the future of the world in other ways in the last third of this century. ”188 Assuming that presidential remark upon the importance of economic power to be valid, it is necessary to get a deeper sense of the transformations which were occurring in the global economy since the early years of the Cold War; for although international trade and prosperity were to be subject to some unusual turbulences (especially in the 1970s), certain basic longterm trends can be detected which seemed likely to shape the state of world politics into the foreseeable future.

1971年7月,理查德·尼克松在堪萨斯城对一群新闻媒体人发表讲话时再次指出:当今世界上存在着5支经济力量——西欧、日本、中国以及苏联和美国。“这5支经济力量将决定世界经济的前途和本世纪最后1/3时间中世界其他方面的未来,因为经济力量是决定其他各种力量的关键。”假如经济力量果真如总统所说的那么重要,那么就很有必要对“冷战”早期以来世界经济变化的情况进行更深入的了解。因为,尽管国际间的贸易与繁荣难免受到偶然动乱的影响(尤其在20世纪70年代),一些可能构成可以预见到的未来世界政治格局基本的长期发展趋势还是可以探测的。

As with all of the earlier periods covered in this book, there can be no exactitude in the comparative economic statistics used here. If anything, the growth in the number of professional statisticians employed by governments and by international organizations and the development of much more sophisticated techniques since the days of Mulhall’s Dictionary of Statistics have tended to show how difficult is the task of making proper comparisons. The reluctance of “closed” societies to publish their figures, differentiated national ways of measuring income and product, and fluctuating exchange rates (especially after the post-1971 decisions to abandon a gold-exchange standard and to adopt floating exchange rates) have all combined to cast doubt upon the correctness of any one series of economic data. 189 On the other hand, a number of statistical indications can be used, with a reasonable degree of confidence, to correlate with one another and to point to broad trends occurring over time.

正如本书前面所有的部分一样,此处用以进行比较的经济统计数字并不精确。更何况自从马尔霍尔所著的统计学字典问世以来,各国政府和各个国际组织所聘用的专业统计学家人数不断增加,统计技术日趋复杂,要进行确切的比较又谈何容易!“封闭”社会不愿公布统计数字,各国对收入和生产的统计方法不同,汇率动荡不定(尤其是在1971年决定放弃黄金-美元本位,实行浮动汇率制后),这一切给任何一个系列经济统计数字的正确性都投下了怀疑的阴影。但另一方面,具有相当可信度的统计数字所揭示的蛛丝马迹,又可以用来发掘其内在联系,进而推导出今后发展的大趋势。

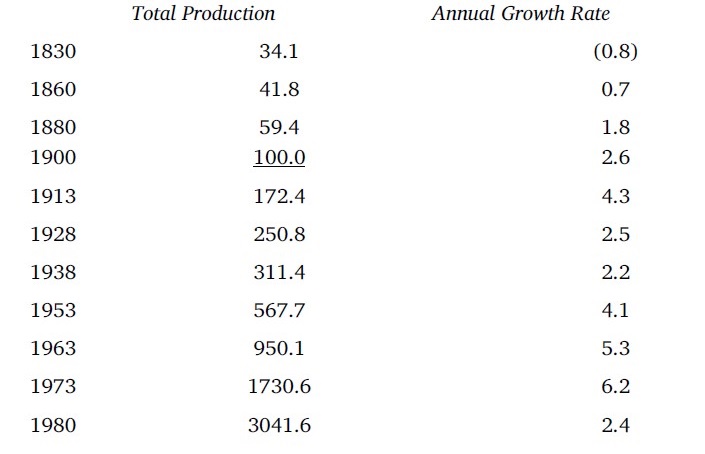

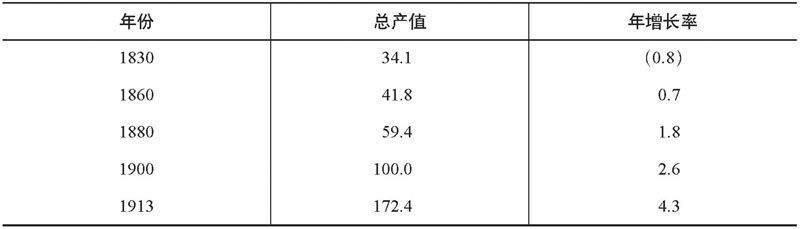

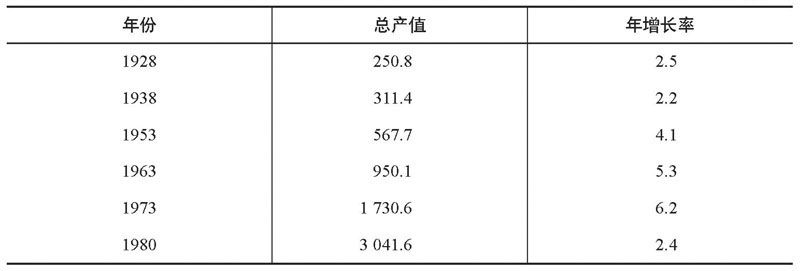

The first, and by far the most important, feature has been what Bairoch rightly describes as “a totally unprecedented rate of growth in world industrial output”190 during the decades after the Second World War. Between 1953 and 1975 that growth rate averaged a remarkable 6 percent a year overall (4 percent per capita), and even in the 1973–1980 period the average increase was 2. 4 percent a year, which was very respectable by historical standards. Bairoch’s own calculations of the “production of world manufacturing industries”—essentially confirmed by Rostow’s figures on “world industrial production”191— give some sense of this dizzy rise (see Table 39).

贝尔罗克把第二次世界大战以后第一个也是迄今为止最重要的一个经济特点,正确地描述为“一个绝对空前的世界工业生产增长率”。1953~1975年,年均总增长率达到令人瞩目的6%(人均产值为4%),即使在1973~1980年,年平均增长率也达到了2.4%。按照历史上的标准,这一水平是相当了不起的。贝尔罗克本人计算的“世界制造业生产”统计数字,与罗斯托的“世界工业生产”数字基本吻合,前者提供了下面一组令人目眩的增长数字(见表39)。

Table 39. Production of World Manufacturing Industries, 1830–1980192

表39 世界制造业生产统计数字(1830~1980年)

(1900 = 100)

(1900年为100)

(续)

As Bairoch also points out, “The accumulated world industrial output between 1953 and 1973 was comparable in volume to that of the entire century and a half which separated 1953 from 1800. ”193 The recovery of war-damaged economies, the development of new technologies, the continued shift from agriculture to industry, the harnessing of national resources within “planned economies,” and the spread of industrialization to the Third World all helped to effect this dramatic change.

贝尔罗克还指出:“1953~1973年世界累计工业产量可与1800~1953年的一个半世纪的总产量相媲美。”遭到战争破坏的经济的恢复、新技术的发展、持续不断的由农业向工业的转化、在“计划经济”的范围内对自然资源的利用以及将工业化扩展到第三世界等,这一切都有助于这个戏剧性的变化。

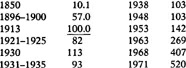

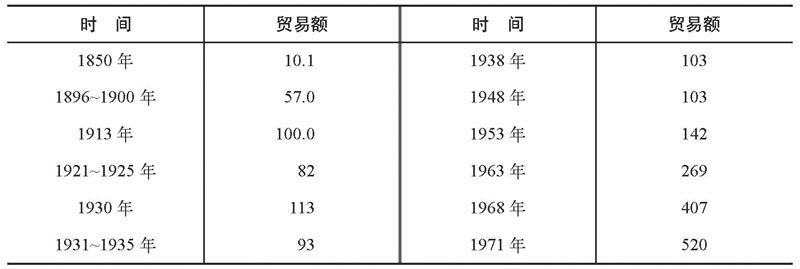

In an even more emphatic way, and for much the same reasons, the volume of world trade also grew spectacularly after 1945, in contrast to the distortions of the era of the two world wars:

更进一步说,由于同样的原因,与两次世界大战扭曲了的时代相比较,1945年之后世界贸易的增长也足以令人惊讶(见表40)。

Table 40. Volume of World Trade, 1850-1971194

表40 世界贸易额(1850~1971年)

(1913 = 100)

(1913年为100)

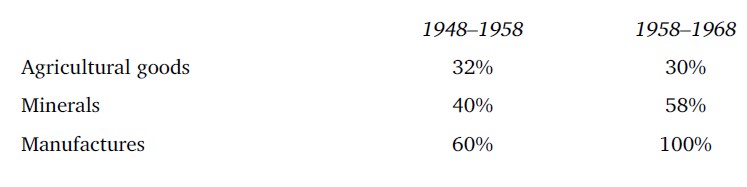

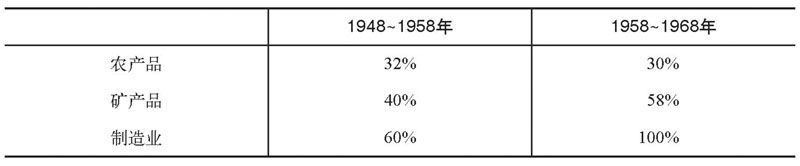

What was more encouraging, as Ashworth points out, was that by 1957, for the first time ever world trade in manufactured goods exceeded those in primary produce, which itself was a consequence of the fact that the increase in the overall output of manufactures during these decades was considerably larger than the (very impressive) increases in agricultural goods and minerals (see Table 41).

更加令人鼓舞的是——正如阿什沃思所指出的——到了1957年,世界制造业产品的贸易额有史以来首次超过了初级产品。这是几十年来制造业总产量的增长大大超过农产品和矿产品的增长(也相当可观)的结果(见表41)。

Table 41. Percentage Increases in World Production, 1948–1968195

表41 世界生产增长百分比(1948~1968年)

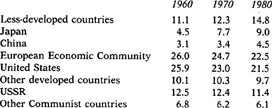

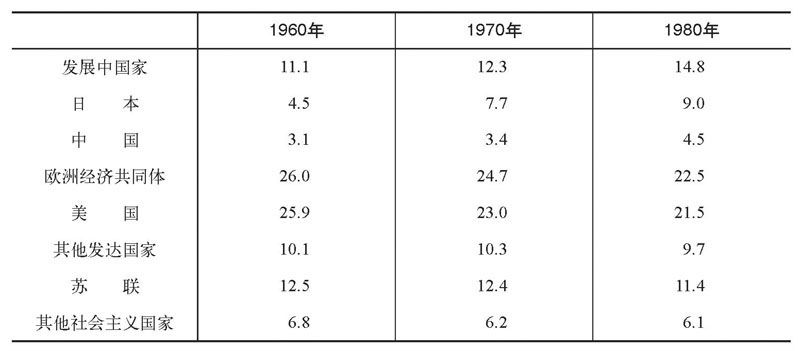

To some extent, this disparity can be explained by the great increases in manufacturing and trade among the advanced industrial countries (especially those of the European Economic Community); but their rising demand for primary products and the beginnings of industrialization among an increasing number of Third World countries meant that the economies of most of the latter were also growing faster in these decades than at any time in the twentieth century. 196 Notwithstanding the damage which western imperialism did to many of the societies in other parts of the world, the exports and general economic growth of these societies do appear to have benefited most when the industrialized nations were in a period of expansion. Less-developed countries (LDCs), argues Foreman- Peck, grew rapidly in the nineteenth century when “open” economies like Britain’s were expanding fast—just as they were the worst hit of all when the industrial world fell into depression in the 1930s. During the 1950s and 1960s, they once again experienced faster growth rates, because the developed countries were booming, raw-materials demand was rising, and industrialization was spreading. 197 After its nadir in 1953 (6. 5 percent), Bairoch shows the Third World’s share of world manufacturing production rising steadily, to 8. 5 percent (1963), then 9. 9 percent (1973), and then 12. 0 percent (1980). 198 In the CIA’s estimates, the lessdeveloped countries’ share of “gross world product” has also been increasing, from 11. 1 percent (1960), to 12. 3 percent (1970), to 14. 8 percent (1980). 199

上述差异,在一定程度上可从制造业以及发达的工业国家(特别是欧洲经济共同体国家)之间贸易的巨大增长中得到说明。但是,工业化国家对初级产品日益旺盛的需求,与越来越多的第三世界国家开始实行工业化这一事实,意味着大部分第三世界国家的经济发展速度近几十年来要比20世纪以往任何时候都快。尽管西方帝国主义曾给世界其他地区的社会带来损害,但当工业化国家进入扩张时期时,这些社会的出口和整个经济的增长受益最大。福尔曼·佩克认为,19世纪,当发达国家的“开发型”经济(如英国那样)迅速向外扩张的时候,发展中国家的经济也蒸蒸日上——反之亦然,当20世纪30年代工业化国家陷入大萧条阶段时,发展中国家的经济所遭受的打击也最大。20世纪50~60年代,发达国家的经济再度繁荣,对原材料的需求急剧增长,发展中国家因而又出现了较大的增长率,工业化程度进一步提高。贝尔罗克的统计表明,第三世界国家的制造业生产在世界同行业中所占的比重稳步增长,以1953年为起点(6.5%),1963年上升为8.5%,1973年为9.9%,1980年达12%。据美国中央情报局估计,发展中国家在世界生产总值中所占的比重也一直呈增长的趋势,从1960年的11.1%增至1970年的12.3%,再增至1980年的14.8%。

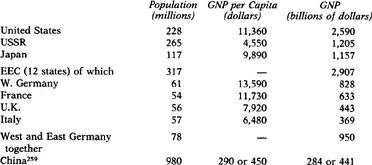

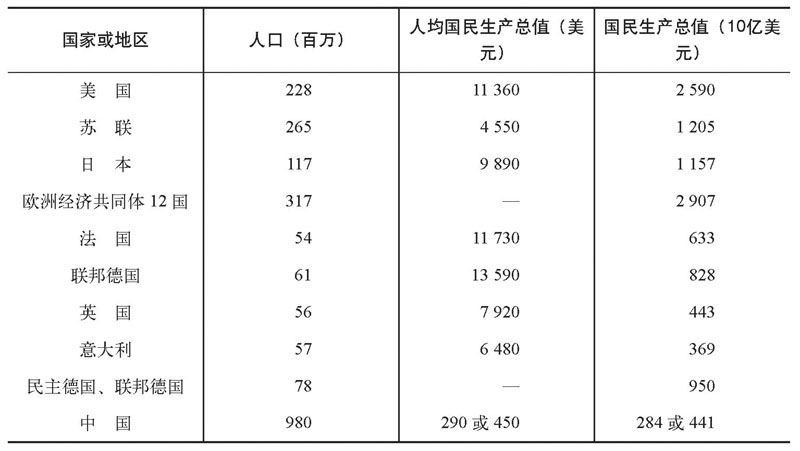

Given the sheer number of people in the Third World, however, their share of world product was still disproportionately low—and their poverty horrifically manifest. The average GNP per capita in the industrialized countries was $10,660 in 1980, but only $1,580 per capita for the middle-income countries like Brazil, and a shocking $250 per capita for the very poorest Third World countries like Zaire. 200 For the fact was that while their proportion of world product and manufacturing output was arising as a whole, the gain was not shared in equal proportion by all of the LDCs. Differences in wealth between some countries in the tropics were large even as the colonialists withdrew—just as they had been, in many cases, before the imperial era. They were exacerbated by the uneven pattern of demand for the countries’ products, by the varying levels of aid which each managed to secure, and by the vicissitudes of climate, politics, tampering with the environment, and economic forces quite outside their control. Drought could devastate a country for years. Civil wars, guerrilla activities, or the forced resettlement of peasants could reduce agricultural output and trade. Sinking world prices, say, of peanuts or tin could almost bring a single-product economy to a halt. Soaring interest rates, or a rise in the value of the U. S. dollar, could be body blows. A spiraling population growth, caused by western medical science’s success in checking disease, increased the pressure upon food stocks and threatened to wipe out any gains in overall national income. On the other hand, there were states which went through a “green revolution,” with agricultural output boosted by improved farming techniques and new strains of plants. In addition, the massive earnings recorded by those countries lucky enough to possess oil in the 1970s turned them into a different economic category—although even these so-called OPEC-LDCs suffered as oil prices tumbled in the early 1980s. Finally, in one of the most significant developments of all, there arose among Third World countries a number of what Rosecrance terms “the trading states”— South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia, imitating Japan, West Germany, and Switzerland in their entrepreneurship and commitment to produce industrial manufactures for the global market. 201

然而,如果按照第三世界绝对人口数进行平均,其在世界生产总值中所占的比重仍然不成比例,其贫穷程度实在令人惊讶。1980年,发达工业国家人均国民生产总值为10660美元,像巴西这样中等收入的国家为l580美元,而像扎伊尔这样的第三世界穷国却只有250美元。事实上,发展中国家虽然制造业总增长比例日益上升,但各个国家的受益却并不均等。早在帝国主义到来之前、殖民主义者撤走之后(许多国家的确撤走了),一些热带地区国家之间就存在着相当悬殊的贫富差别。由于这些国家产品的需求量不均衡,由于它们所能够得到的援助多寡不一,由于政治、气候的变化对环境带来不利的影响,以及国家难以控制的经济力量的作用等,这种差距进一步扩大了。旱灾可以使一个国家连年田园荒芜;内战、游击队的活动以及对农民的强行迁移,可造成农业减产和贸易萎缩。花生和锡等产品的国际市场价格下跌,可能导致单一产品的经济停滞不前。频频上升的利率或美元的增值,更使这些国家受到沉重的打击。由于西方医学在防治疾病方面所取得的成就,许多国家人口数目扶摇直上,它增加了粮食紧张的压力并使新增的国民收入消耗殆尽。另一方面,也有许多国家进行了“绿色革命”,它们通过改进农业技术和改良作物与植物品种,增加了农产品的产量。另外,那些在20世纪70年代吉星高照、收入颇丰的产油国,经济上变成了另一种类型——所谓不发达的欧佩克国家(石油输出国),尽管它们在20世纪80年代初由于油价下跌而吃了苦头。在所有的发展中,最引人注目的是罗斯克兰称之为“贸易国”的几个第三世界国家和地区:南朝鲜、中国台湾、新加坡和马来西亚。它们模仿日本、联邦德国和瑞士的企业家精神,为世界市场生产工业产品。

This disparity among less-developed nations points to the second major feature of macroeconomic change over the past few decades—the differential growth rates among the various nations of the globe, which was as true of the larger, industrialized Powers as it was of the smaller countries. Since this trend is the one which—on the record of the preceding centuries—has ultimately had the greatest impact upon the international power balances, it is worth examining in some detail how it affected the major nations in these decades.

发展中国家之间的差别表明,过去几十年宏观经济变化的第二个特点是:世界上不同国家的经济有不同的发展速度,无论是工业大国还是落后小国,都是如此。这一趋势在过去的几个世纪内,曾对国际力量对比产生了十分重大的影响。因此,它在最近几十年里对主要国家的影响如何,值得仔细考察。

There can be no doubt that the economic transformation of Japan after 1945 offered the most spectacular example of sustained modernization in these decades, outclassing almost all of the existing “advanced” countries as a commercial and technological competitor, and providing a model for emulation by the other Asian “trading states. ” To be sure, Japan had already distinguished itself almost a century earlier by becoming the first Asian country to copy the West in both economic and —fatefully for itself—military and imperialist terms. Although badly damaged by the 1937–1945 war, and cut off from its traditional markets and suppliers, it possessed an industrial infrastructure which could be repaired and a talented, welleducated, and socially cohesive population whose determination to improve themselves could now be channeled into peaceful commercial pursuits. For the few years after 1945, Japan was prostrate, an occupied territory, and dependent upon American aid. In 1950, the tide turned—ironically, to a large degree because of the heavy U. S. defense spending in the Korean War, which stimulated Japan’s exportoriented companies. Toyota, for example, was in danger of foundering when it was rescued by the first of the U. S. Defense Department’s orders for its trucks; and much the same happened to many other companies. 202

毫无疑问,1945年之后的日本经济,几十年来在持续进行现代化方面树立了蔚为壮观的榜样。日本在商业和竞争方面成绩突出,不仅在发达国家中独执牛耳,而且也为亚洲其他贸易国提供了可资仿效的模式。事实上,日本在一个世纪以前,就是亚洲第一个模仿西方经济,效仿西方的军事和帝国主义(这对它来说是致命的)的国家,并因此而令人刮目相看。尽管日本在1937~1945年的战争中遭到严重破坏,并丧失了传统的市场和原料供应国,但日本仍具有可以进行修复的工业基础,拥有聪明能干、受过良好教育、具有社会凝聚力的人民,他们要求改善自我的决心可以被引导到从事和平的商业追求上来。1945年战争结束之后的几年里,日本作为一个被占领国,服服帖帖,依赖于美国的援助。1950年,形势开始逆转。具有讽刺意味的是,美国在朝鲜战争中庞大的开支,极大地刺激了日本的许多出口型公司的生产。例如,丰田公司当时已面临危机,但美国国防部的首批卡车订单使它得救了。其他一些公司也有类似的经历。

There was, of course, much more to the “Japanese miracle” than the stimulant of American spending during the Korean War and, again, during the Vietnam War; and the effort to explain exactly how the country transformed itself, and how others can imitate-its success, has turned into a miniature growth industry itself. 203 One major reason was its quite fanatical belief in achieving the highest levels of quality control, borrowing (and improving upon) sophisticated management techniques and production methods in the West. It benefited from the national commitment to vigorous, high-level standards of universal education, and from possessing vast numbers of engineers, of electronics and automobile buffs, and of small but entrepreneurial workshops as well as the giant zaibatsu. There was social ethos in favor of hard work, loyalty to the company, and the need to reconcile managementworker differences through a mixture of compromise and deference. The economy required enormous amounts of capital to achieve sustained growth, and it received just that—partly because there was so little expenditure upon defense by a “demilitarized” country sheltering under the American strategic umbrella, but perhaps even more because of fiscal and taxation policies which encouraged an unusually high degree of personal savings, which could then be used for investment purposes. Japan also benefited from the role played by MITI (its Ministry for International Trade and Industry) in “nursing new industries and technological developments while at the same time coordinating the orderly run-down of aging, decaying industries,”204 all this in a manner totally different from the American laissez-faire approach.

除了美国在朝鲜战争以及后来的越南战争中的军事开支对日本经济起了刺激作用外,造就“日本奇迹”的当然还有很多其他因素。通过对日本发展道路及成功经验的探讨,可以看出工业自身发展的一个缩影。日本成功的一个主要原因是,它对获得高水平的质量控制具有坚定的信念。它从西方移植了(并不断加以改进)复杂的管理技术和生产方法。它在全国大力推行高水平的普及教育,因而拥有大批电子、机械工程师和汽车迷,以及大量规模虽小但属于企业型的小工厂以及财团。日本社会崇尚勤奋工作的精神,人们忠于自己服务的公司,主张通过相互妥协和彼此尊重来调解劳资纠纷。要实现持续的经济增长,需要大量的资金,日本获得了这种资金。其方法是,一方面借助于美国的战略保护伞,实行国家“非军事化”,在防务上花费极少;另一方面,更重要的是,实行鼓励个人储蓄的金融税务政策,使个人储蓄额高得令人叹为观止。这些钱可用来投资。日本的成功还得益于通商产业省“对新兴企业和技术发展的扶持,以及对陈旧和衰败企业进行的有条不紊的淘汰”。所有这些与美国自由放任的做法大不相同。

Whatever the mix of explanations—and other experts upon Japan would point more strongly to cultural and sociological reasons, not to mention that indefinable “plus factor” of national self-confidence and willpower in a people whose time has come—there was no denying the extent of its economic success. Between 1950 and 1973 its gross domestic product grew at the fantastic average of 10. 5 percent a year, far in excess of that of any other industrialized nation; and even the oil crisis in 1973–1974, with its profound blow to world expansion, did not prevent Japan’s growth rates in subsequent years from staying almost twice as large as those of its major competitors. The range of manufactures in which Japan steadily became the dominant world producer was quite staggering—cameras, kitchen goods, electrical products, musical instruments, scooters, on and on the list goes. Japanese products challenged the Swiss watch industry, overshadowed the German optical industry, and devastated the British and American motorcycle industries. Within a decade, Japan’s shipyards were producing over half of the world’s tonnage of launchings. By the 1970s, its more modern steelworks were turning out as much as the American steel industry. The transformation of its automobile industry was even more dramatic—between 1960 and 1984 its share of world car production rose from 1 percent to 23 percent—and in consequence Japanese cars and trucks were being exported in their millions all over the world. Steadily, relentlessly, the country moved from low-to high-technology products—to computers, telecommunications, aerospace, robotics, and biotechnology. Steadily, relentlessly, its trade surpluses increased—turning it into a financial giant as well as an industrial one—and its share of world production and markets expanded. When the Allied occupation ended in 1952, Japan’s “gross national product was little more than one-third that of France or the United Kingdom. By the late 1970s the Japanese GNP was as large as the United Kingdom’s and France’s combined and more than half the size of America’s. ”205 Within one generation, its share of the world’s manufacturing output, and of GNP, had risen from around 2–3 percent to around 10 percent—and was not stopping. Only the USSR in the years after 1928 had achieved anything like that degree of growth, but Japan had done it far less painfully and in a much more impressive, broader-based way.

对日本的奇迹无论如何解释(某些日本问题专家更加强调其文化、社会因素,至于国民的自信心和意志力这种“附加因素”就更不用说了),谁都不会否认日本所取得的巨大的经济成就。1950~1973年,日本国内生产总值年平均增长率达到难以置信的10.5%,这一比例远远高于其他所有的工业国。即使在1973~1974年世界经济受到石油危机沉重打击之时,日本经济的发展也没有受到阻碍。此后,日本的经济增长率几乎一直高出竞争对手一倍。作为世界制造业稳定的主要生产者,日本生产的产品很多,有照相机、厨房用品、电子产品、乐器和摩托车等,并且不断有新的产品问世。日本的产品已经向瑞士的手表工业提出了挑战,也使德国的光学工业黯然失色,并使得英、美摩托车工业蒙受损失。日本的造船厂10年之内所生产的吨位数,占世界下水船舶吨位的一半以上。到了20世纪70年代,日本现代化的钢厂的产量已与美国钢铁工业持平。日本汽车业的变化更富有戏剧性。1960~1984年,日本汽车在国际市场上所占的比例从1%上升到23%——结果日本向全世界出口的小汽车和卡车都数以百万计。日本锲而不舍、咄咄逼人,产品从低技术向高技术迈进:计算机、电信、航天、机器人以及生物工程等。也正是这种锲而不舍、咄咄逼人的努力,使日本的贸易顺差增加,成为金融和工业的巨人,它在世界生产和市场中所占的比重也随之扩大。1952年,当盟军结束军事占领时“日本的国民生产总值仅比英国或法国的国民生产总值的l/3略高一点。但到了20世纪70年代后期,日本的国民生产总值已相当于英、法两国的总和以及美国的一半以上”。在不到30年的时间内,日本在世界制造业生产和国民经济总产值中所占的比例,从大约2%~3%上升到约10%,并且从未止步。世界上只有苏联在1928年之后的若干年里曾达到过类似的增长速度,但日本却来得更加轻松自如,既有更广泛的基础,也更加令人瞩目。

By comparison with Japan, every other large Power must seem economically sluggish. Nonetheless, when the People’s Republic of China (PRC) began to assert itself in the years after its foundation in 1949, there were few observers who did not take it seriously. In part this may have reflected a traditional worry about the “Yellow Peril,” since the sleeping giant in the East would clearly be a major force in world affairs just as soon as it had organized its 800 million population for national purposes. More important still was the very prominent, not to say aggressive, role which the PRC adopted toward foreign Powers almost since its inception, even if that may have been a nervous response to its perceived encirclement. The clashes with the United States over Korea and Quemoy and Matsu; the move into Tibet; the border struggles with India; the angry break with the USSR, and military confrontations in the disputed regions; the bloody encounter with North Vietnam; and the generally combative tone of Chinese propaganda (especially under Mao) as it criticized western imperialism and “Russian hegemonism” and urged on people’s liberation movements across the globe made it a much more important, but also more incalculable, figure in world affairs than the discreet and subtle Japanese. 206 Simply because China possessed one-quarter of the world’s population, its political lurches in one direction or another had to be taken seriously.

与日本相比,其他各个大国的经济发展显得缓慢。然而,中华人民共和国1949年诞生之后,开始显示了它的威力,当时只有极少数观察家没有认真看待它。这部分地反映了传统上对于所谓“黄祸”的忧虑,因为这个东方巨人一旦组织起全国的8亿人口,在国际事务中显然是一支巨大的力量。更重要的是,它从诞生之日起在同列强的交往中所起的突出的(更不用说敢作敢为的)作用,尽管也许这是由于它感到自己被包围而做出的一种反应。它同美国在朝鲜和中国金门、马祖的冲突;解放西藏;它同印度进行的边境冲突;它愤然同苏联决裂,并在有争议的边境地区进行军事交锋;它同越南进行流血的反击作战;它在批判西方帝国主义和“苏联霸权主义”方面,在促进全世界民族解放运动方面,通常使用一种积极的宣传调子(特别是在毛泽东时期),所有这些使它在世界事务中树立了一个比言行谨慎、精明敏捷的日本更为重要、更难以预测的形象。仅仅从中国拥有世界1/4的人口这一点说,无论其政治倾向如何,都必须予以认真的对待。

Nevertheless, measured on strictly economic criteria, the PRC seemed a classic case of economic backwardness. In 1953, for example, it was responsible for only 2. 3 percent of world manufacturing production and had a “total industrial potential” equal only to 71 percent of Britain’s in 1900!207 Its population, leaping upward by tens of millions of new mouths each year, consisted overwhelmingly of poor peasants whose per capita output was dreadfully low and rendered the state little in terms of “added value. ” The disruption caused by the warlords, the Japanese invasion, and then the civil war of the late 1940s was not stopped when the peasant communes took over from the landowners after 1949. Nevertheless, economic prospects were not entirely hopeless. China did possess a basic infrastructure of roads and light railways, its textile industry was substantial, its cities and ports were centers of entrepreneurial activity, and the Manchurian region in particular had been developed by the Japanese during the 1930s. 208 What the country required, if it was to enter the stage of industrial takeoff, was a long period of stability and massive infusions of capital. Both conditions were achieved to some degree— because of the dominance of the Communist Party, and the flow of Russian aid—as the 1950s evolved. The Five-Year Plan of 1953 consciously imitated those Stalinist priorities of developing heavy industry and of increasing steel, iron and coal production. By 1957, industrial output had doubled. 209 On the other hand, the amount of ready capital for industrial investment, whether raised internally or borrowed from Russia, was quite insufficient for a country of China’s economic needs—and the Sino-Soviet split brought Russian financial and technical aid to an abrupt halt. In addition, Mao’s fatuous decisions to achieve a “Great Leap Forward” by encouraging thousands of cottage-sized steelworks and his campaign for the “Cultural Revolution” (which led to the disgrace of technical experts, professional managers, and trained economists) slowed development considerably. Finally, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the PRC’s confrontationist diplomacy and its military clashes with almost all of its neighbors meant that far too large a proportion of the country’s scarce resources had to be devoted to the armed forces.

但是,如果用严格的经济学标准衡量,中国似乎又是典型的经济落后国家。比如说,1953年,中国在世界制造业中所占的比例仅有2.3%,其工业潜力仅相当于英国1900年的71%。中国的人口每年以数以千万计的高速度增长,占人口绝大多数的贫穷的农民,其人均产值低得可怕,上缴国家的“附加值”很少。20世纪以来,中国的发展受到过许多干扰:军阀混战、日本入侵、40年代末的内战等,直到1949年才告结束,农民才从地主的手中夺回了土地。然而,中国经济的前途并非没有希望。中国过去就拥有公路、轻型铁路等基础设施,它的纺织业很有潜力,其城市和港口已成为企业活动的中心,特别是中国东北地区在20世纪30年代曾被日本开发过。中国的工业要想腾飞,必须具备两个条件:长期的安定和巨额的投资。在20世纪50年代,由于有共产党领导和苏联的援助,上述两个条件在某种意义上是具备了。1953年的第一个五年计划,仿效斯大林优先发展重工业和增加钢、铁、煤产量的做法,到了1957年,其工业生产翻了一番。但是另一方面,无论是从国内筹集到的还是从苏联借来的资金,都远远不能满足中国经济发展的需要;后来中苏关系破裂,苏联突然终止了对中国的经济和技术援助。此外,鼓励开办乡村钢铁厂以求取“大跃进”,发动“文化大革命”(使大批技术专家、专业管理人员和训练有素的经济学家受到冲击)等,极大地阻碍了中国的发展。还有,在整个20世纪50年代和60年代,中国实行敌对性的外交政策,与几乎所有的邻国发生过军事冲突,这意味着其有限的财力相当一部分必须用于军事开支。

The period of the Cultural Revolution was not all bad in economic terms; it did at least emphasize the importance of the rural areas, stimulating small-scale industries as well as improved farming techniques, and bringing basic medical and social care to the villages. 210 Nevertheless, significant increases in national product could come only from further industrialization, infrastructural improvements, and long-term investments—all of which were aided by the winding down of the Cultural Revolution and by the growth of trade with the United States, Japan, and other advanced economies. China’s own coal and oil resources were being swiftly exploited, as were its stocks of many precious minerals. By 1980, its steel output of 37 million tons was well in excess of that of Britain or France, and its consumption of energy from modern sources was twice that of any of the leading European states. 211 By that date, too, its share of world manufacturing production had risen to 5. 0 percent (from 3. 9 percent in 1973), and was closing upon West Germany’s. 212 This heady recent growth has not been unattended by problems, and the party leadership has had to readjust downward the targets for the country’s “four modernizations”; it is also worth repeating that when any of China’s statistics of wealth or output are presented in per capita terms, its relative economic backwardness is again revealed. Yet, notwithstanding those deficiencies, it became clear over time that the Asian giant was at last on the move and determined to build an economic foundation adequate for its intended role as a Great Power. 213

当然,就经济而论,这一时期并非一无是处。它至少强调乡村地区的重要性,促进了小型工业的发展,改善了农业技术,给乡村带来了基本的医疗和社会保障。但是,中国只有进一步改善基础设施和实行工业现代化,并进行长期的投资——在“文化大革命”以后休养生息,同美、日等发达国家增加贸易——才能使国民生产获得重大提高。中国的煤炭、石油同其他贵重金属矿产一样,正在被迅速开发。到1980年,中国的钢产量达3700万吨,大大超过英国或法国,其现代能源消耗相当于欧洲任何一个主要国家能耗的两倍。同年,中国在世界制造业中所占的比重也上升(从1973年的3.9%)到5%,接近于联邦德国所占的比例。但是,近年来在这种喜人的增长形势中并非没有问题,共产党领导人已不得不调低了国家的“四化”目标。而且值得重提的是,如果财富和产值按人口平均数统计,中国又会重新显现出它经济相对落后的面貌。当然,尽管有种种不足,中国这个亚洲巨人已经苏醒了,它决心建立起与大国地位相称的经济基础。

The fifth region of economic power identified by Nixon in his July 1971 speech had been “western Europe,” which was of course more of a geographical expression than a unified assertive Power like China, the USSR, and the United States. Even the term itself meant different things to different people—it could be all of those countries outside the Russian-dominated sphere (and therefore include Scandinavia, Greece, and Turkey), or it could be the original (or enlarged) European Economic Community, which at least possessed an institutional framework, or it was often used as a shorthand for that cluster of formerly great states (Britain, France, Germany, Italy) which might need to be consulted, say, by the U. S. State Department before the latter initiated a new policy toward Russia or in the Middle East. Even that did not exhaust the possibilities of semantic confusion, since for much of this period the British regarded “Europe” as beginning on the other side of the English Channel; and there were, moreover, many committed European integrationists (not to mention German nationalists) who regarded the post-1945 division of the continent as a merely temporary condition, to be followed in the future by a joining of the countries of both sides into some larger union. Politically and constitutionally, therefore, it has been difficult to use the term “Europe” or even “western Europe” as more than a figure of speech—or a vague cultural-geographical concept. 214

尼克松在1971年7月的一次公开讲话中认为,第五个经济实力强大的地区是“西欧”。相比中、美、苏这些国家来说,西欧显然更多地具有地理上的概念,而且,这一概念本身的含义就因人而异——西欧可以是指在苏联控制势力范围以外的所有国家(包括斯堪的纳维亚半岛国家、希腊和土耳其),也可以是指最初的(或者扩大以后的)欧洲共同体国家(它们至少拥有一个共同的经济机构),它还常用来代指那些老牌的强国(英、法、德、意)。如果美国国务院要实行一项新的对苏政策或中东政策,它就不能不同这些国家协商。由于近代以来,英国人一般认为“欧洲”起始于英吉利海峡的彼岸,所以,不能完全排除这一概念在语义上含糊不清的可能性;更何况还有许多主张欧洲一体化的欧洲人(德国的民族主义者就更不必说了),他们把1945年以后欧洲大陆的分裂看作是一种暂时状态,主张将来把两边的国家组织成一个大联邦。因此,从政治和法规上说,使用“欧洲”或“西欧”一词来表达超出词义和含混的人文地理概念本身的含义,是有困难的。

At the economic level, however, there did seem to be a basic similarity in what was being experienced across Europe in these years. The most outstanding feature was the “sustained and high level of economic growth. ”215 By 1949–1950, most countries were back to their prewar levels of output, and some (especially, of course, the wartime neutrals) were significantly ahead. But there then followed year after year of increased manufacturing output, of unprecedented levels of growth in exports, of a remarkable degree of full employment and historically high levels of disposable income as well as of investment capital. The result was to make Europe the fastest-growing region in the world, Japan excepted. “Between 1950 and 1970 European gross domestic product grew on average at about 5. 5 percent per annum and 4. 4 percent on a per capita basis, as against world average rates of 5. 0 and 3. 0 percent respectively. Industrial production rose even faster at 7. 1 percent compared with a world rate of 5. 9 percent. Thus by the latter date output per head in Europe was almost two and a half times greater than in 1950. ”216 Interestingly enough, this growth was shared in all parts of the continent—in northwestern Europe’s industrial core, in the Mediterranean lands, in eastern Europe; even the sluggish British economy grew faster during this period than it had for decades. Not surprisingly, Europe’s relative place in the world economy, which had been declining since the turn of the century, soon began to expand. “During the period 1950 to 1970 her share of world output of goods and services (GDP) rose from 37 to 41 percent, while in the case of industrial production the increase was even greater, from 39 to 48 percent. ”217 Both in 1960 and in 1970, the CIA figures were showing—admittedly on statistical evidence that can be disputed218— that the “European Community” possessed a larger share of gross world product than even the United States, and that it was twice as large as the Soviet Union’s.

从经济角度上看,欧洲各国最近几十年的情况基本相似,最为突出的特征是高速持续增长。到1949~1950年,大多数欧洲国家恢复到了它们战前的生产水平,其中一些国家(主要是战时的中立国)的生产还明显超过了战前水平。紧接着,欧洲的工业产量逐年增加,出口额空前增长,就业相当充分,可自由支配的收入与投资金额创历史的高水平,其结果是使欧洲成为除日本以外的世界上经济增长最快的地区。1950~1970年,欧洲各国的国内生产总值年均增长率为5.5%,人均产值增长4.4%,而相应的世界平均增长率则分别为5%与3%。工业的增长率还要高些,达7.1%,相比之下,世界增长率仅为5.9%。到了这一阶段的后期,欧洲的人均产值几乎相当于1950年的2.5倍。极其有趣的是,这种增长的趋势遍及整个欧洲,包括西北欧这个工业中心、地中海沿岸国家和东欧国家,连一向发展缓慢的英国经济,此时也以几十年前从未有过的速度快步向前发展。20世纪初以来,欧洲在世界经济中下降了的地位很快得到了回升。“1950~1970年,欧洲在世界商品和服务业产值中所占的比例,从37%增加到41%;而工业产值增长更大,从39%增至48%。”美国中央情报局1960年和1970年的统计数字表明(他们承认这些数字是有争议的),欧洲共同体在世界总产值中的比重比美国还大,为苏联的两倍。

The reasons for Europe’s economic recovery are, on reflection, not at all surprising. For too long, much of the continent had suffered from invasions, prolonged fighting and foreign occupation, bombings of towns, factories, roads, and railways, shortages of food and raw materials caused by blockade, the call-up of millions of men and killing off of millions of animals. Even before the fighting, Europe’s “natural” economic development—that is, growth which evolved region by region, as new sources of energy and production revealed themselves, as new markets took off, as new technology spread—had been distorted by the actions of the nationalistically inclined Machtstaat219 Ever-higher tariff barriers had separated suppliers from their markets. Government subventions had kept inefficient firms and farmers protected from foreign competition. Increasingly large amounts of national income had been devoted to armaments spending rather than commercial enterprise. It was thus impossible to maximize Europe’s economic growth in this “climate of blocks and autarky, of economic nationalism, and of gaining benefits by hurting others. ”220 Now, after 1945, there were not only “new Europeans” like Monnet, Spaak, and Hallstein determined to create economic structures which would avoid the mistakes of the past, but there was also a helpful and bénéficient United States, willing (through the Marshall Plan and other aid schemes) to finance Europe’s recovery provided it was done as a cooperative venture.

促使欧洲经济复兴的原因,探究起来一点儿也不令人惊讶。长期以来,大多数欧洲国家饱受侵略、长期战争与外国占领之痛苦,城市、工厂、公路、铁路遭到轰炸;封锁导致食品与原材料匮乏;千百万人民应征入伍,千百万生灵惨遭涂炭。即使在战前,欧洲经济的“自然”发展也受到有民族主义倾向的军国主义的阻碍。所谓“自然”经济的发展,就是随着新的能源和新的生产资料的出现,随着新的市场的产生和新技术的推广,生产发展在一个地区一个地区地扩展。不断增高的关税壁垒曾使产品供应国与市场相隔绝。政府的补贴使低效的公司和农场主在同外国的竞争中得到保护。越来越多的国家财政收入被用于军事开支,而不是用于商业企业。因此,在这种“相互封锁、自给自足、自然经济和损人利己的社会风气中,欧洲的经济不可能获得充分的发展”。1945年以后,不仅莫内、斯佩克和哈尔斯坦等“新一代欧洲人”决心创造能免蹈覆辙的新的经济结构,而且还有心肠不错、乐于助人的美国,它愿意以合作的方式(通过实施马歇尔计划和其他援助计划)为欧洲的经济复兴提供财政援助。

Thus, a Europe whose economic potential had been distorted and underutilized by war and politics now had a chance to correct those deficiencies. There was a broad determination to “build anew” in both eastern and western parts of the continent, and a willingness to learn from the follies of the 1930s. State planning, whether of the Keynesian or socialistic variety, gave a concentrated thrust to this desire for social and economic improvement; the collapse (or discrediting) of older structures made innovation easier. The United States not only gave billions of dollars of Marshall Plan aid—“a shot in the arm at a critical time,” as it was aptly described221 —but also provided a defense umbrella under which the European states could shelter. (It was true that both Britain and France spent heavily on defense during the Korean War years and the period before their decolonizations—but they, and all their neighbors, would have had to devote much more of their scarce national resources to armaments had they not been protected by the United States. ) Because there were fewer trade barriers, firms and individuals were able to flourish in a much larger market. This was especially so since trade among developed countries (in this case, the European states themselves) was always more profitable than trade elsewhere, simply because the mutual demand was greater. If the “foreign” trade of Europe rose faster than anything else in these decades, therefore, it was chiefly because much more buying and selling was going on among neighbors. In one generation after 1950, per capita income increased as much as it had during the century and a half prior to that date!222 The socioeconomic pace of this change was truly remarkable: the share of West Germany’s working population engaged in agriculture, forestry and fishing dropped from 24. 6 percent in 1950 to 7. 5 percent in 1973, and in France it fell from 28. 2 percent to 12. 2 percent in the same period (and to 8. 8 percent in 1980). Disposable incomes boomed as industrialization spread; in West Germany per capita income soared from $320 in 1949 to $9,131 in 1978, and in Italy it rose from $638 in 1960 to $5,142 in 1979. The number of automobiles per 1,000 of population rose from 6. 3 in West Germany (1948) to 227 (1970), and in France from 37 to 252. 223 However one measured it, and despite continued regional disparities, the evidence of very real gains was clear.

因此,过去因战争和政治等原因而不能充分发挥和运用其经济潜力的欧洲,现在终于有机会弥补过去的不足了。欧洲大陆(无论东欧和西欧)普遍存在着重建新欧洲的决心和从20世纪30年代的愚蠢行径中吸取教训的心愿。无论是凯恩斯主义者还是社会主义者,在制订国家计划时,其重点都在于推动社会和经济发展;旧的结构解体或被怀疑和否定,使革新变得更加容易。美国不仅按马歇尔计划向欧洲提供了数百万美元的援助——被恰当地比喻为“雪中送炭”——而且在军事上还提供了一把保护伞,使欧洲各国得到庇护。在朝鲜战争期间以及非殖民化前的时期里,英、法两国确曾把巨额资金用于国防。假如没有美国的保护,它们和所有的邻国就要把有限的资源更多地用于军备。因为贸易壁垒少了,公司和个人便能够在更大的市场范围内获得发展。在发达国家之间所进行的贸易(欧洲国家本身即是如此),因为它们相互间的需求更大,所以总是比同其他国家进行贸易更加有利可图。假如说欧洲国家的“对外”贸易额比其他事业的增长要快,那么,主要原因是欧洲各国的买卖主要是在邻国之间进行的。1950年后的大约30年里,欧洲人均收入的增长额相当于以前一个半世纪增长额的总和。社会经济的发展速度的确令人吃惊,比如,联邦德国从事农业、林业和渔业的人口比例,从1950年的24.6%下降为1973年的7.5%;同期,法国则从28.2%降为12.2%(1980年进而降为8.8%)。随着工业化的发展,可自由支配的收入急剧增加;联邦德国的人均收入从1949年的320美元,猛增至1978年的9131美元;意大利从1960年的638美元,增为1979年的5142美元。联邦德国每千人的汽车拥有数量从1948年的6.3辆增至1970年的227辆;法国则从37辆增为252辆。无论你对此作何评价,尽管还存在着地区差异,但实实在在的增长是有目共睹的。

This combination of general economic growth, together with wide variations in both the rate of change and its effects, can clearly be seen if one examines what happened in each of the former Great Powers. South of the Alps, there occurred what journalists hyperbolically termed “the Italian miracle,” with the country’s GNP in real terms rising nearly three times as fast after 1948 than it had during the interwar years; indeed, until 1963, when growth slowed, the Italian economy rose faster in these years than that of any other country except Japan and West Germany. Yet perhaps that, too, is not surprising in retrospect. It was always the least developed of the European “Big Four,” which is another way of saying that its potential for growth had not been as fully exploited. Freed from the absurdities of fascist economic policies, and benefiting strongly from American aid, Italian manufacturers were able to utilize the country’s lower wage costs and strong reputation in design to boost exports at an amazingly fast rate, especially within the Common Market. Hydroelectricity and cheaply imported oil compensated for the lack of indigenous coal supplies. Motor construction was a great stimulant. As local consumption levels boomed, FIAT, the domestic automobile producer, occupied an unchallenged position for many years in this home market, giving it a strong base for its export drive north of the Alps. Traditional manufactures, like shoes and fine clothes, were now joined by newer products; Italian refrigerators outsold any others in Europe by the 1960s. This was not, by any means, a story of unqualified success. The gap between north and south in Italy remained chronic. Social conditions, both in the inner cities and in the poorer rural areas, were far worse than in northern Europe. Governmental instability, a large “black economy,” and a high public deficit, together with a higher than average inflation rate, affected the value of the lira and suggested that this economic recovery was a fragile one. Whenever European-wide comparisons of income, or industrialization, were made, Italy did not compare too well with its more advanced neighbors; when growth rates were compared, things looked much better. That is simply another way of saying that Italy had started from a long way behind. 224

如果考察一下每个老牌强国所发生的变化,便可以清楚地看出,经济的总增长伴随着各种不同的发展速度,产生了不同的影响。在阿尔卑斯山以南,出现了一种特别引人注目的现象,记者们夸张地称之为“意大利奇迹”。意大利的国民生产总值在1948年之后以3倍于战争期间的速度飞速增长,这一势头一直持续到1963年才减慢下来。在此期间,除日本和联邦德国以外,意大利的经济发展速度比任何国家都快。然而,回想起来,这种现象也并不奇怪。意大利一直属于“欧洲四强”之末,换言之,它以前从未充分发挥出自己的经济潜力。意大利摆脱了法西斯主义荒唐的经济政策,加之美国的有力援助,企业家们利用国家规定的低工资带来的低成本和设计方面的声誉,以惊人的速度发展了出口业,特别是对共同市场的出口。意大利利用水力发电和廉价进口的石油,补偿了本国煤炭供给的不足。汽车制造业的成就则给意大利的经济发展增添了催化剂。由于意大利汽车需求与消费量增大,菲亚特汽车制造厂生产的汽车在国内市场的地位经久不衰,这为它向阿尔卑斯山以北的国家出口汽车奠定了有力基础。与此同时,制鞋业和优质服装业等传统制造业,不断向市场推出新的产品。至20世纪60年代,意大利冰箱畅销欧洲所有国家。但是上述成功绝非毫无缺陷。意大利南北方之间的差距依然长期存在;而且,无论城市或者乡村,各方面的社会条件都远不如北欧国家;政府稳定;有大规模的“黑市经济”,高额的财政赤字以及高于各国平均值的通货膨胀率等。这些都影响了里拉的价值,并且表明意大利的经济复兴是脆弱的。每当同欧洲各国的收入或工业化程度做比较,意大利总是比不上其发达的邻国,但若拿增长率做比较,情况就好得多,这又说明意大利经济的起点较低。

By contrast, Great Britain in 1945 was a long way ahead, at least among the larger European states; which may be part of the explanation for its relative economic decline during the four decades following. That is to say, since it (just like the United States) had not been so badly damaged by the war, its rate of growth was unlikely to be as high as in those countries recovering from years of military occupation and damage. Psychologically, too, as has been discussed above,225 the fact that Britain was undefeated, that it was still one of the “Big Three” at Potsdam, and that it regained all of its worldwide empire made it difficult for people to see the need for drastic reforms in its own economic system. Far from producing newer structures, the war had preserved traditional institutions such as trade unions, the civil service, the ancient universities. Although the Labor administration of 1945– 1951 pushed ahead with its plans for nationalization and for the creation of a “welfare state,” a more fundamental restructuring of economic practices and of attitudes to work did not occur. Confident still in its special place in the world, Britain continued to rely upon captive colonial markets, struggled in vain to preserve the old parity for sterling, maintained extensive overseas garrisons (a great drain on the currency), declined to join in the early moves toward European unity, and spent more on defense than any of the other NATO powers apart from the United States itself.

相比之下,1945年的英国经济处于遥遥领先的地位,至少在欧洲大国中是如此,也许这从一个方面说明了在往后40年中英国经济相对衰退的缘由。也就是说,由于英国(同美国一样)没有遭到战争的严重破坏,其增长率不可能像那些从军事铁蹄下与战争破坏中恢复过来的国家一样高。至于心理方面的因素,正如前面所述,英国并未被打败,它依然是“波茨坦三强”之一,并重新获得了其世界帝国的一切,这种事实使英国国民很难产生彻底改革其自身经济制度的愿望。英国战后没有建立什么新的机构,而是保留了传统的工会、行政机构和古老的大学。虽然工党政府1945~1951年推出国有化和建立“福利国家”的计划,但并非更加深入地对经济机构和工作态度进行重新调整。因为英国依然自信在世界上居于特殊的地位,它继续依靠所猎取的殖民地市场,竭力维持英镑价值,但结果却是徒劳的。英国保留了大量的海外驻军(耗费了大量金钱),并拒绝加入欧洲统一进程。在北约国家中,其军费开支仅次于美国。

The frailty of Britain’s international and economic position was partially disguised in the early post-1945 period by the even greater weakness of other states, the prudent withdrawals from India and Palestine, the short-term surge in exports, and the maintenance of empire in the Middle East and Africa. 226 The humiliation at Suez in 1956 therefore came as a greater shock, since it revealed not only the weakness of sterling but also the blunt fact that Britain could not operate militarily in the Third World in the face of American disapproval. Nonetheless, it can be argued that the realities of decline were still disguised—in defense matters, by the post-1957 policy of relying upon the nuclear deterrent, which was far less expensive than large conventional forces yet suggested a continued Great Power status; and in economic matters, by the fact that Britain also shared in the general boom of the 1950s and 1960s. If its growth rates were about the lowest in Europe, they were nevertheless better than the expansion of previous decades and thus allowed Macmillan to claim to the British electors, “You’ve never had it so good!” Measured in terms of disposable income, or numbers of washing machines and automobiles, that claim was historically correct.

1945年后初期的英国,因为其他国家更为明显的缺陷,以及它深谋远虑地从印度和巴勒斯坦撤出,一时的出口增长和在中东与非洲的帝国地位得以维持,这一切都使得它在国际和经济上的真实地位被部分地掩盖起来了。1956年,埃及将苏伊士运河收归国有,给了英国当头一棒,这不仅暴露了英镑的疲软无力,同时也表明了一个无可辩驳的事实:如果没有得到美国的许可,英国就休想在第三世界国家动用武力。有人可能会说,英国的衰落更是被以下做法和事实进一步掩盖了。在防务方面,1957年以后,它开始执行倚重于核威慑的政策,这要比庞大的常规力量省钱,但却仍可表明其大国地位依旧。在经济方面,英国同样分享了20世纪50年代和60年代的经济繁荣。虽然说英国经济的增长率在欧洲几乎是最低的,但它比以前几十年的情况总算好一些。难怪麦克米伦对英国的选民说:“你们从未有过这样好的境况!”如果从可自由支配的收入、洗衣机和小汽车的数量来衡量,麦克米伦的说法具有历史的正确性。

Measured against the much faster progress being made elsewhere, however, the country appeared to be suffering from what the Germans unkindly termed “the English disease”—a combination of militant trade unionism, poor management, “stop-go” policies by government, and negative cultural attitudes toward hard work and entrepreneurship. The new prosperity brought a massive surge in imports of better-designed European products and of cheaper Asian wares, in turn leading to balance-of-payments difficulties, sterling crises, and devaluations which helped to fuel inflation and thus higher wage demands. Price controls, legislation on wage increases, and fiscal deflation were employed at various times by British governments to check inflation and create the right circumstances for sustained growth. They rarely worked for long. The British automobile industry was steadily undermined by its foreign competitors, the once-booming shipbuilding industry grew to depend almost solely upon Admiralty orders, the producers of electrical goods and motorbikes found that they could no longer compete. Some companies (like ICI) were notable exceptions to this trend; the City of London’s financial services held up well, and retailing remained strong—but the erosion of Britain’s industrial base was remorseless. Joining the Common Market in 1971 did not provide the hoped-for panacea: it exposed the British market to even greater competition in manufactures, while tying Britain into the expensive farm-price policies of the EEC. North Sea oil also proved less than a godsend: it brought Britain massive foreign-currency earnings, but that so drove up the price of sterling that it hurt manufacturing exports. 227

但是,与其他一些发展速度更快的国家相比,正如德国人所讥讽的那样,“英国得了‘英国病’”,即好战的工会制度、低劣的管理、政府的“原地踏步”政策、在文化上对刻苦工作和企业家进取精神持否定态度等混合在一起的综合征。在新的经济繁荣形势下,英国大量进口设计更为精美的欧洲产品和亚洲的廉价商品,随之导致收支失去平衡、英镑危机和贬值,加剧了通货膨胀,人们要求增加工资的呼声更加强烈。在不同的时期,英国政府采取了控制市场价格、制定提薪法规和收紧银根等一些措施来制止通货膨胀,为经济的持续发展创造有利的环境,但这些措施很少能够长久地发挥作用。英国的汽车工业逐步受到外国竞争者的削弱;曾经盛极一时的造船工业,变得越发依赖于海军一家的订货。电子产品与摩托车的生产厂家失去了市场竞争能力。在这一趋势下,也有一些公司(如帝国化学公司)例外。伦敦商业区的金融业运作良好,零售业也依然十分发达。但是,受到侵蚀的英国工业基础却已无法挽回。1971年,英国加入共同市场,但并未从那里得到它所希望的灵丹妙药。英国一方面把自己拴在欧洲共同体实行的农产品高价政策上,同时把国内市场敞开,引来了制造业更为激烈的竞争。北海油田也并非天赐宝物,它虽然为英国赚取了大量的外汇,但又使得英镑升值,损害了英国工业品的出口。

The economic statistics offer a measure of what Bairoch terms “the acceleration of the industrial decline of Great Britain. ”228 Its share of world manufacturing production slipped from 8. 6 percent in 1953 to 4. 0 percent in 1980. Its share of world trade also fell away swiftly, from 19. 8 percent (1955) to 8. 7 percent (1976). Its gross national product, third-largest in the world in 1945, was overtaken by West Germany’s, then by Japan’s, then by France’s. Its per capita disposable income was steadily overtaken by a host of smaller but richer European countries; by the late 1970s it was closer to those of Mediterranean states than to those of West Germany, France, or the Benelux countries. 229 To be sure, much of this decline in Britain’s shares (whether of world trade or world GNP) was due to the fact that special technical and historical circumstances had given the country a disproportionately large amount of global wealth and commerce in earlier decades; now that those special circumstances had gone, and other countries were able to exploit their own potential for industrialization, it was natural that Britain’s relative position should slip. Whether it should have slipped so much and so fast is another issue; whether it will slip further, relative to its European neighbors, is equally difficult to say. By the early 1980s, the decline seemed to be leveling off, leaving Britain still with the world’s sixth-largest economy, and with very substantial armed forces. By comparison with Lloyd George’s time, or even with Clement Attlee’s in 1945, however, it was now just an ordinary, moderately large power, not a Great Power.

经济统计数字向人们表明,的确出现了贝尔罗克所说的“大不列颠工业衰退的加速度”。英国在世界制造业生产中所占的比重从1953年的8.6%,降为1980年的4%。英国在世界贸易中所占的比重也急转直下,从1955年的19.8%降为1976年的8.7%。1945年,英国国民生产总值居世界第三位,但后来联邦德国、日本、法国一一超过了它,欧洲许多富裕的小国人均收入也纷纷超过了它。到了20世纪70年代末,英国可自由支配的人均收入被联邦德国、法国以及比利时、荷兰、卢森堡抛在后面,降为更加接近于地中海国家的水平。当然,英国在世界贸易或国民生产总值中所占比重的下降,还应归咎于这样的事实:由于特殊的技术与历史条件,英国在早些年曾拥有与其本身不相称的过多的财富与贸易额,既然那些特殊条件已不复存在,其他国家已经有能力发挥自己的潜力,那么,英国的地位相应下降乃理所必然。至于英国的地位下降得如此之快是否正常,如此之大,则又当别论。与其欧洲邻国相比,英国的地位今后是否还会进一步下降,目前也还难以预料。20世纪80年代初期,英国的经济衰退趋势呈现出一种平稳的状态。它仍然是世界第六经济大国,而且拥有一支庞大的武装力量。与劳埃德·乔治时代甚至1945年的克莱门特·艾德礼时代相比,英国无论知何也算不上一个泱泱大国,而只不过是一个普通的中等大国罢了。

While the British economy was languishing in relative decline, West Germany was enjoying its Wirtschaftswunder, or “economic miracle. ” Once again, it is worth stressing how “natural,” relatively speaking, this development was. Even in its truncated state, the Federal Republic possessed the most developed infrastructure in Europe, contained large internal resources (from coal to machine-tool plants), and had a highly educated population, perhaps especially strong in managers, engineers, and scientists, which was swollen by the emigration of talent from the east. For the past half-century or more, its economic powers had been distorted by the requirements of the German military machine. Now that the national energies could (as in Japan) be concentrated solely upon commercial success, the only question was the extent of the recovery. German big business, which had accommodated itself fairly easily to the Second Reich, to Weimar, and then to the Nazi period of rule, had to adjust to the new circumstances and pick up American management assumptions. 230 The big banks were once again able to play a large role in the direction of industry. The chemical and electrical industries soon reemerged to be the giants of European industry. Massively successful automobile companies, like Volkswagen and Mercedes, had their inevitable “multiplier effects” upon hundreds of small supplier firms. As exports boomed—Germany became second only to the United States in world export trade—increasing number of firms and local communities needed to bring in “guest workers” to meet the crying demand for unskilled labor. Once again, for the third time in a hundred years, the German economy was the powerhouse of Europe’s economic growth. 231

正当英国的经济在相对衰落中失去活力的时候,联邦德国则在创造“经济奇迹”。这里有必要再次强调,这种发展相对来讲是十分“正常”的。即使在分裂状态下,联邦德国仍拥有欧洲最发达的基础设施,拥有丰富的国内资源(从煤一直到机床厂),同时还拥有受过良好教育的国民,这一点在管理人员、工程师和科学家中表现得特别明显。其中有不少人才是从民主德国逃过来的。在过去半个多世纪的时间里,德国的经济力量都因国家军事机器的需要而走上了邪道。现在其国家的力量可以(像在日本一样)投入商业成就之中,唯一的问题只是恢复的程度。德国的大企业曾轻易地适应了第二帝国、魏玛共和国以及纳粹统治的需要,现在不得不适应新的环境,学习美国的管理思想。它的大银行再一次得以朝着工业发展的方向发挥重大作用。它的化学和电气工业不久也东山再起,成为欧洲工业中的巨人。大量卓有成效的汽车公司,比如大众和梅赛德斯(奔驰),对数以千计的供应厂商具有必然的“增效作用”。随着出口的兴旺,德国已成为世界出口贸易中仅次于美国的出口大国。越来越多的公司和经济社区要求吸收“外来务工人员”以满足其对非技术工人的迫切需要。德国经济再一次——这是100年中的第三次——成为欧洲经济发展的“发电厂”。

Statistically, then, the story seemed one of unbroken success. Even between 1948 and 1952, German industrial production rose by 110 percent and real GNP by 67 percent. 232 With the country having the highest gross investment levels in Europe, German firms benefited immensely from their ready access to capital. Steel output, virtually nonexistent in 1946, was soon the largest in Europe (over 34 million tons by 1960), and the same was true of most other industries. Year after year, the country had the largest growth in gross domestic product. Its GNP, a mere $32 billion in 1952, was the biggest in Europe (at $89 billion) by a decade later, and was over $600 billion by the late 1970s. Its per capita disposable income, a modest $1,186 in 1960 (when the United States’ was $2,491), was an imposing $10,837 in 1979— ahead of the American average of $9,595. 233 Year after year, export surpluses were built up, with the deutsche mark needing frequent upward adjustment, and indeed becoming a sort of reserve currency. Although naturally worried at the competition posed by the even more efficient Japanese, the West Germans were undoubtedly the second most successful among the larger “trading states. ” This was the more impressive since the country had been separated from 40 percent of its territory and over 35 percent of its population; ironically, the German Democratic Republic was soon to show that it was the most productive and industrialized per capita of all of the eastern European states (including the USSR) despite the loss of millions of its talented labor force to the West. Had it been possible to return to the 1937 boundaries, a united Germany would once again have been far ahead of any economic rival in Europe and, indeed, perhaps not significantly behind the much larger USSR itself.

从统计方面来看,联邦德国的历史好像是一系列不断成功的记录。即使在1948年和1952年间,德国的工业生产也增长了11%,实际国民生产总值增长了67%。随着它的总投资额达到欧洲最高水平,德国厂商能获取现成的资本,从中得到巨大好处。它的钢产量在1946年实际上还等于零,不久就居欧洲之首(到1960年超过了3400万吨),其他的工业也都取得了大致相同的成就。在国内总产值方面,它每一年都取得最高的增长率。德国国民生产总值在1952年只有320亿美元,而10年之后却跃居欧洲第一(约890亿美元),到20世纪70年代末又超过了6000亿美元。其人均可支配收入在1960年不过1186美元(当时美国为2491美元),到1979年已猛增至10837美元,超过了美国的9595美元的人均数。年复一年,德国的出口盈余日渐积聚,随之而来的是德国马克的比价经常向上调整,实际上已成了一种储备货币。面对来自效率更高的日本的竞争,尽管联邦德国自然会有所担心,但它已毋庸置疑地成为世界“贸易大国”中第二个最成功的国家。由于这个国家有40%的领土和超过35%的人口被分裂开了,联邦德国的这一成就更显得突出。具有讽刺意味的是,民主德国也很快表明,在所有东欧国家(包括苏联)中,尽管自己有数百万优秀劳动力流入联邦德国,但按人口计算,它的劳动生产率最高,工业化程度也最高。假设有可能恢复到1937年的疆界,那么一个统一的德国将会再次把欧洲所有的经济对手远远地甩在后面,比起较自己庞大得多的苏联,也不会逊色多少。

Precisely because Germany had been defeated and divided, and because its international status (and that of Berlin) continued to be regulated by the “treaty powers,” this economic weight did not translate into political might. Feeling a natural responsibility toward Germans in the east, the Federal Republic was peculiarly sensitive to any warming or cooling in the NATO-Warsaw Pact relationship. It had the largest trade with eastern Europe and the USSR, yet it was obviously in the front line should another war occur. Soviet and (only slightly less) French alarm at any revival of “German militarism” meant that it could never become a nuclear Power. It felt guilty toward neighbors like the Poles and the Czechs, vulnerable toward Russia, heavily dependent upon the United States; it welcomed with gratitude the special Franco-German relationship offered by de Gaulle, but rarely felt able to use its economic muscle to control the more assertive policies of the French. Engaged in a profound intellectual confrontation with their own past, the West Germans were very happy to be seen as good team players, but not as decisive leaders in international affairs. 234

正是由于德国的战败和分裂,也由于它的国际地位(还有柏林的地位)继续受到共管德国的“四强”的控制,它的经济实力才未能转化成政治力量。由于深感对东部的德国人负有天然的责任,所以联邦德国对北约-华约关系的冷暖格外敏感。联邦德国是西欧国家中同东欧和苏联贸易量最大的国家,然而一旦战争爆发,它又明显地处于最前线。苏联和(稍次于它的)法国对“德国军国主义”的任何些微复活的警觉,决定了联邦德国永远也不能成为核国家。它对像波兰人和捷克人这样的邻国有一种负疚感,对苏联则感到易受攻击,对美国则是严重地依赖,它满怀感激之情欢迎戴高乐倡导的法德特殊关系,但却很少感到自己能运用经济力量来控制法国执拗自信的政策。由于在理智上同自己的过去进行深刻对抗,联邦德国对于自己在国际事务中被视为一个很好的团体行动成员而不是一个决定性领袖,感到十分高兴。

This contrasted very markedly, then, with France’s role in the postwar world or, more accurately, in the post-1958 world, when de Gaulle took over the helm of the state. As mentioned above (pp. 401–2), the economic progress which the planners around Monnet hoped to achieve after 1945 had been affected by colonial wars, party-political instability, and the weakness of the franc. Yet even at the time of the Indochinese and Algerian campaigns the French economy was growing fast. For the first time in many decades, its population was increasing, and thus fueling domestic demand. France was a rich, varied, but half-developed land, its economy stagnant since the early 1930s. Merely with the coming of peace, the infusion of American aid, the nationalization of utilities, and the stimulus of a larger market, growth was likely. Furthermore, France (like Italy) had a relatively low per capita level of industrialization, because of its small-town, agriculture-heavy economy, which meant that the increases in that regard were quite spectacular: from 95 in 1953, to 167 in 1963, to 259 in 1973 (relative to U. K. in 1900 = 100). 235 The annual rate of growth reached an average of 4. 6 percent in the 1950s, and spurted to 5. 8 percent in the 1960s, under the impetus of Common Market membership. The particular arrangements of the latter not only protected French agriculture from world-market prices, but gave it a large market within Europe. The general boom in the West aided the export of France’s traditional high-added-value wares (clothes, shoes, wines, jewelry), which were now joined by aircraft and automobiles. Between 1949 and 1969, automobile production rose tenfold, aluminum sixfold, tractors and cement fourfold, iron and steel two and a half times. 236 The country had always been relatively rich, if underindustrialized; by the 1970s, it was a lot richer, and looked altogether more modern.

这同法国在战后世界,更准确地说是在1958年戴高乐任总统以后的世界中所发挥的作用,形成了鲜明对比。如上所述,以莫内为首的计划者们在1945年以后所希望取得的经济成就,一直受到它所进行的殖民战争、国内政党政治的动荡以及法郎疲软的冲击。然而,正是在印度支那战争和阿尔及利亚民族解放战争期间,法国的经济得到了迅速发展。几十年来,法国的人口第一次有了增长,从而刺激了国内的需求。法国虽然富足、多样化,但却属于半发达国家,自从20世纪30年代以来它的经济一直停滞不前。只是由于和平的降临、美国援助的输入、公用事业国有化和广阔市场的推动,才使得它的增长成为可能。进一步讲,法国(像意大利一样)的工业化水平按人口计算相对低下,因为它的经济以城镇小工业和农业为主,而这意味着它在经济上取得的成就相当引人注目:从1953年的指数95增长到1963年的167和1973年的259(同英国1900年的指数为100相对比)。在20世纪50年代,它的年增长率平均达到4.6%,60年代由于有共同市场的推动又上升到5.8%。欧洲共同市场的特殊措施不仅保护了法国农业免受世界市场价格波动的冲击,而且也为它的发展提供了庞大的欧洲市场。西方世界的普遍繁荣也促进了法国传统的高附加值商品(服装、鞋子、葡萄酒和珠宝)的出口,飞机和汽车也成了它的主要出口货物。在1949~1969年,法国的汽车生产增加到10倍,铝产量增加到6倍,拖拉机和水泥产量增加到4倍,钢铁产量增加到2.5倍。即使工业化水平不高,相对说来法国也一直是富裕的;到70年代,它就更加富裕了,而且看起来更加现代化了。

Nevertheless, France’s growth was never as broadly based industrially as that of its neighbor across the Rhine, and President Pompidou’s hopes that his country would soon overtake West Germany had little prospect of realization. With certain notable exceptions in the electrical, automobile, and aerospace industries, most French firms were still small and undercapitalized, and the prices of their products were too high compared with Germany’s. Despite the “rationalization” of agriculture, many smallholdings remained—and were, in fact, sustained by the Common Market subvention policies; yet the pressures upon rural France, together with the social strain of industrial modernization (closing old steelworks, etc. ) provoked outbursts of working-class discontent, of which the most famous were the 1968 riots. Poor in indigenous fuel supplies, France became heavily dependent upon imported oil, and (despite its ambitious nuclear-energy program) its balance of payments heavily fluctuated according to the world price of oil. Its trade deficit with West Germany steadily increased, and necessitated regular (if embarrassed) devaluations against the deutsche mark—which was probably a more reliable measure of France’s economic standing than the wild fluctuations in the dollar-franc exchange rate. Even in periods of sustained economic growth, then, there was a certain precariousness to the French economy—which, in the event of shock, sent many prudent bourgeois across the Swiss frontier, bearing the family savings.

不过,法国的增长并不像它的莱茵河邻国那样广泛地依靠工业,蓬皮杜总统要很快超过联邦德国的理想也毫无实现的迹象。除了电气、汽车和航天工业这几个明显的例外,法国的大多数工厂规模小、投资少,而它们的产品价格却比德国高。尽管它推行了农业“合理化”改革,大量的小农经济仍然存在,而且实际上还受到了共同市场补贴政策的庇护。然而,对法国农业的压力,加上工业现代化(包括关闭旧的钢铁厂等)所带来的社会紧张,引发了工人阶级的不满,其中最著名的例子就是1968年爆发的“五月风暴”。由于本国燃料供应的短缺,法国严重依赖进口石油,并且(尽管它有雄心勃勃的核能计划)其国际收支受到世界石油价格波动的严重影响。它同联邦德国的贸易赤字直线上升,而且又需要经常使法郎对马克贬值;但这同美元、法郎比价的经常上下波动比较起来,也许是保持法国经济地位的较可靠的办法。甚至在经济持续增长的时期,法国的经济也面临某种危险,一旦经济动荡不安,许多稳健的资本家便携带着全家的积蓄逃到瑞士。

Yet France always had an impact upon affairs far larger than might be expected from a country with a mere 4 percent of the world GNP—and this was true not merely of the period of de Gaulle’s presidency. It may have been due to sheer national-cultural assertiveness,237 and that coinciding with a time when Anglo- American influences were waning, Russia was appearing more and more unattractive, and Germany was deferential. If western Europe was to have a leader and spokesman, France was a more obvious candidate than the isolationist British or the subdued Germans. Furthermore, successive French administrations quickly recognized that their country’s modest real power could be buttressed by persuading the Common Market to adopt a particular line—on agricultural tariffs, high technology, overseas aid, cooperation at the United Nations, policy toward the Arab- Israeli conflict, and so on—which effectively harnessed what had become the world’s largest trading bloc to positions favored by Paris. None of this restrained France from quite unilateral actions when the occasion seemed to merit it.

但是,法国对世界事务的影响,总是远远超过人们对这么一个仅占世界国民生产总值4%的国家的期望值,而且不仅在戴高乐任总统时期是如此。也许这应归因于法国那种国民文化中十足的自信精神,而且这同英美影响的下降、苏联对世界吸引力的日渐微弱以及德国谨慎从事的时代相巧合。如果西欧真要有一个领袖和代言人,那么法国将胜过孤立主义的英国和被征服的德国而成为当然的候选人。进而言之,法国历届政府很快就认识到,通过说服共同市场遵循一条特殊的路线——在农业关税、高技术、海外援助、联合国内的合作、对阿以冲突的政策等方面——以有效地利用巴黎倡导的、现已成为世界上最大贸易集团的欧洲共同市场这一有利地位,就能大大加强自己本不甚强的力量,提高自己的影响。而一旦时机成熟,以上任何一点又都难以阻止它采取单边的行动。

The fact that all four of these larger European states grew in wealth and output during these decades, together with their smaller neighbors, was not a guarantee of everlasting happiness. The early hopes toward ever-closer political and constitutional integration foundered upon the still-strong nationalism of its members, shown first of all by de Gaulle’s France, and then by those states (Britain, Denmark, Greece) which had only later, and more warily, joined the EEC. Economic disputes, especially over the high cost of the farm-support policy, often paralyzed affairs in Brussels and Strasbourg. With neutral Eire a member, it was not possible to effect a common defense policy, which had to be left to NATO (from whose command structure the French had now absented themselves). The shock of the oil price rises in the 1970s seemed to hit Europe especially badly, and to take the steam out of the earlier optimism; despite widespread alarm, and considerable planning in Brussels, it seemed difficult to evolve high-technology policies to counter the Japanese and American challenges. Yet, notwithstanding these many difficulties, the sheer economic size of the EEC meant that the international landscape was now significantly different from that of 1945 or 1948. The EEC was by far the largest importer and exporter of the world’s goods (although much of that was intra- European trade), and it contained, by 1983, by far the largest international currency and gold reserves; it manufactured more automobiles (34 percent) than either Japan (24 percent) or the United States (23 percent) and more cement than anyone else, and its crude-steel production was second only to that of the USSR. 238 With a total population in 1983 significantly larger than the United States’ and almost exactly the same as Russia’s—each having 272 million—the ten-member EEC had a substantially bigger GNP and share of world manufacturing production than the Soviet state, or the entire Comecon bloc. If politically and militarily the European Community was still immature, it was now a much more powerful presence in the global economic balances than in 1956.

上述4个较大的欧洲国家的财富和生产在这几十年的增长,加上邻国弱小这一事实,并不能保证在它们之间实现永久的和睦。早期对日益紧密的政治和制度一体化的期望损害了共同市场成员国中仍然强烈的民族主义,这首先在戴高乐的法国身上,尔后是那些姗姗来迟的、怀着戒备之心参加欧洲共同体的国家(英国、丹麦、希腊)身上表现出来。他们之间的经济分歧,尤其是在高额农业补贴计划上的矛盾,常常使共同体在布鲁塞尔和斯特拉斯堡的会议日程陷入瘫痪。由于中立的爱尔兰参加了共同体,因而也就不可能形成一个共同的防御政策;这一使命不得不留给北约(法国现已退出北约的指挥机构)去完成。20世纪70年代石油价格上涨的冲击对欧洲的打击特别沉重,似乎一下子打消了人们早期的乐观主义。尽管惊恐四起,共同体官员们也做了大量的计划工作,但是要制定出一套发展高技术的政策以对付日本和美国的挑战,仍然步履艰难。然而,不论有多少困难曲折,欧洲经济共同体经济发展的现实规模已意味着,国际形势已完全不同于1945年或1948年了。欧洲经济共同体已成为世界最大的货物进出口地区(尽管相当一部分属于欧洲内部贸易),到1983年,它已拥有世界最多的货币和黄金储备;它生产的汽车(占世界产量的34%),比日本(占24%)和美国(占23%)都多,它生产的水泥也多于美日,它的粗钢产量仅次于苏联。1983年,10国共同体的人口总数远远超过美国,而与苏联基本相同——各有2.72亿,它的国民生产总值及其在世界工业生产中所占的比重也大于苏联,甚至比整个经济互助委员会国家的总额都多。即使欧洲共同体在政治上和军事上尚不成熟,但它在全球经济中的地位与1956年相比却强大得多。

Almost exactly the opposite could be said about the USSR, as it evolved from the 1950s to the 1980s. As has been described above (pp. 385–91), these were decades when the Soviet Union not only maintained a strong army, but also achieved nuclear-strategic parity with the United States, developed an oceangoing navy, and extended its influence in various parts of the world. Yet this persistent drive to achieve equality with the Americans on the global scene was not matched by parallel achievements at the economic level. Ironically (given Marx’s stress upon the importance of the productive substructure in determining events), the country which claimed to be the world’s original Communist state appeared to be suffering from increasing economic difficulties as time went on.

几乎与此完全相反的,可说是苏联从20世纪50年代到80年代的演变。如上所述,在这几十年中,苏联不仅保持了它的强大陆军,而且实现了对美国的战略核均势,建立起一支远洋海军,并将其影响扩张到世界的每个角落。然而,想在全球范围内同美国分庭抗礼的持久的竞赛努力,与其在经济领域取得的成就很不相称。颇具讽刺意味的是(马克思强调生产基础在决定社会进程中的作用),将自己标榜为世界上正统的社会主义国家的苏联,却随着时间的流逝而日渐遭受经济困难的折磨。

This is not to gainsay the quite impressive economic progress which was made in the USSR—and throughout the Soviet-dominated bloc—since Stalin’s final years. In many respects, the region was even more transformed than western Europe during those few decades, although that may have been chiefly due to the fact that it was so much poorer and “underdeveloped” to begin with. At any event, measured in crude statistical terms, the gains were imposing. Russia’s steel output, a mere 12. 3 million tons in 1945, soared to 65. 3 million tons in 1960, and to 148 million tons in 1980 (making the USSR the world’s largest producer); electricity output rose from 43. 2 million kilowatt-hours, to 292 million, to 1. 294 billion, during the same periods; automobile production jumped from 74,000 units, to 524,000, to 2. 2 million units; and this list of increases in products could be added to almost indefinitely. 239 Overall industrial output, averaging over 10 percent growth a year during the 1950s, increased from a notional 100 in 1953 to 421 in 1964,240 which was a remarkable achievement—as were such obvious manifestations of Russian prowess as the Sputnik, space exploration, and military hardware. By the time of Khrushchev’s political demise, the country had a far more prosperous, broaderbased economy than under Stalin, and that absolute gain has steadily increased.

这并没否定苏联及其所支配的东欧盟国自斯大林末期以来所取得的显著经济成就。从许多方面来看,苏联和东欧在这几十年里所发生的变化,比起西欧甚至有过之而无不及,尽管这可能主要取决于这样一个事实,即它们的起点很低:贫穷且落后。不论怎样,根据大致的统计数字来看,苏联所取得的成就还是十分显著的。它的钢产量在1945年只有l230万吨,1960年则达到6530万吨,1980年又跃至14800万吨(成为世界上最大的产钢国);发电量在同期内也从每小时4320万瓦,上升到每小时29200万瓦和每小时129400万瓦;汽车产量也从7.4万辆跃至52.4万辆和220万辆;而且这个成就单子还可以无限地开列下去。它的整个工业产量在1950年代平均每年增长10%以上。假定1953年的增长指数为100,那么到1964年这个数字就达到了421,这是令人瞩目的成就。这同苏联的人造卫星上天、太空探索和军事装备上的惊人成就一样,都显示了苏联人的卓越才能。到赫鲁晓夫下台时,苏联的经济比斯大林统治时期要繁荣得多、基础雄厚得多,而且其绝对量一直稳步增长。

There were, however, two serious defects which began to overshadow these achievements. The first was the steady, long-term decline in the rate of growth, with industrial output each year since 1959 dropping from double-digit increases to a lower and lower figure, so that by the late 1970s it was down to 3–4 percent a year and still falling. In retrospect, this was a fairly natural development, since it has now become clear that the early, impressive annual increases were chiefly due to vast infusions of labor and capital. As the existing labor supply began to be fully utilized (and to compete with the requirements of the armed forces, and agriculture), the pace of growth could not help but fall back. As for capital investment, it was heavily directed into large-scale industry and defense-related production, which again emphasized quantitative rather than qualitative growth, and left many other sectors of the economy undercapitalized. Although the standard of living of the average Russian was improved by Khrushchev and his successors, nonetheless consumer demand could not (as in the West) stimulate growth in an economy in which personal consumption was being deliberately kept low in order to preserve national resources for heavy industry and the military. Above all, perhaps, there remained the chronic structural and climatic weaknesses affecting Soviet agriculture, the net output of which grew 4. 8 percent a year in the 1950s but only 3 percent in the 1960s and 1. 8 percent in the 1970s—despite all the attention and capital lavished upon it by anguished Soviet planners and their ministers. 241 Bearing in mind the size of the agricultural sector in the USSR, and the fact that its population rose by 84 million in the three decades after 1950, the overall increases in national product per capita were significantly less than the rates of industrial output, which were in themselves a somewhat “forced” achievement.

然而有两个严重缺陷使这些成就黯然失色。第一点就是苏联经济增长率长期稳步下降。从1959年以来,它的工业生产增长率从每年的两位数向下滑落,越降越低,以至于到20世纪70年代末期每年只有3%~4%,而且仍在下降。回顾历史即可看到,这是一种十分自然的发展,因为越来越明显的是,早期的、突出的增长主要是靠劳力和资本的大量消耗实现的。随着现有劳动力供应的完全使用(而且还要同武装部队、农业进行争夺),增长的速度也就只有下降了。就资本投资来讲,苏联主要是将大量资本倾注在与重工业和国防有关的生产上,而且又往往过分强调数量的增长,忽视了质量的提高,从而使其他众多的经济部门投资不足。虽然苏联的人均生活水平在赫鲁晓夫及其继任者统治下有了提高,但是,在个人消费被人为地控制得很低,以保证将其资源用于重工业和军事方面这样一种经济环境中,消费者的需求(正像在西方一样)无法刺激经济的增长。也许首要的问题仍然是以下两点:长期影响苏联农业僵化的体制和恶劣的气候。因此,不论苦恼的计划人员和部长们为此倾注了多少心血,对农业的投资多么慷慨大方,苏联农业净产量的增长率还是从20世纪50年代的平均4.8%降到60年代的3%和70年代的1.8%。考虑到农业在苏联经济中的地位以及它的人口在1950年以后的30年中增加了8400万,它在人均国民生产总值方面的总的增长要远远低于其工业生产的增长,而后者本身又有点像“强制性”的成就。

The second serious defect was, predictably enough, in terms of the Soviet Union’s relative economic standing. During the 1950s and early 1960s, with its share both of world manufacturing output and of world trade increasing, Khrushchev’s claim that the Marxist mode of production was superior and would one day “bury capitalism” seemed to have some plausibility to it. Since that time, however, the trend has become more worrying to the Kremlin. The European Community, led by its industrial half-giant West Germany, has become much wealthier and more productive than the USSR. The small island state of Japan grew so fast that its overtaking of Russia’s total GNP became merely a matter of time. The United States, despite its own relative industrial decline, kept ahead in total output and wealth. The standard of living of the average Russian, and of his eastern-European confreres, did not close the gap with that in western Europe, toward which the peoples of the Marxist economies looked with some envy. The newer technology, of computers, robotics, telecommunications, revealed the USSR and its satellites as poorly positioned to compete. And agriculture remained as weak as ever, in productive terms: in 1980, the American farm worker was producing enough food to supply sixty-five people, whereas his Russian equivalent turned out enough to feed only eight. 242 This, in turn, led to the embarrassing Soviet need to import increasing amounts of foodstuffs.

第二个严重缺陷是可以充分估计到的、苏联经济的相对停滞。在20世纪50年代和60年代早期,鉴于苏联在世界工业生产和世界贸易增长中所占的比重,赫鲁晓夫宣称马克思主义的生产模式是优越的,并将有朝一日“埋葬资本主义”,看起来还有些道理。但是从那以后,形势变得越来越使克里姆林宫感到担心。欧洲共同体在工业上的“半个巨人”联邦德国的带动下突飞猛进,其富裕程度和生产力水平已远远超过苏联。小小的岛国日本也发展得如此迅速,在国民生产总值上超过苏联仅仅是一个时间问题。美国尽管其工业相对衰落,但在总产量和财富方面仍遥遥领先。苏联及其东欧兄弟国家在人均生活水平上并没有消除同西欧的差距。对此,其人民未免有些羡慕。由于不利的竞争地位,苏联和它的卫星国面对日益更新的计算机、人工智能和电信技术,只能望洋兴叹。而苏联的农业从生产率上来看也仍然同以往一样衰弱不堪:1980年,一个美国农业工人生产出的粮食足够满足65个人的需要,而他的苏联同行生产出的粮食却只能养活8口人。这反过来又使苏联处于不得不越来越多地进口大量粮食的困境之中。

Many of Russia’s own economic difficulties have been mirrored by those of its satellites, which also achieved high growth rates in the 1950s and early 1960s— though again from levels which were low compared with those of the West, and by following priorities which similarly emphasized centralized planning, heavy industry, and collectivization of agriculture. 243 While significant differences in prosperity and growth occurred among the eastern European states (and still do occur), the overall tendency was one of early expansion and then slowdown— leaving Marxist planners with a choice of difficult options. In Russia’s case, additional farmland could be brought under cultivation, though the limits imposed by the winter ecology in the north and the deserts in the south restricted possibilities in that direction (and easily reminded many of how Khrushchev’s confident exploitation of the “virgin lands” soon turned them into dustbowls);244 similarly, more intensive exploitation of raw materials ran the danger of increasing inefficiencies in dealing with, say, oil stocks,245 while extractive costs rose swiftly as soon as mining was extended into the permafrost region. More capital might be poured into industry and technology, but only at the cost of diverting resources either from defense—which has remained the number-one priority of the USSR, despite all the changes of leadership—or from consumer goods—slighting of which was seen to be highly unpopular (especially in eastern Europe) at a time when improved communications were making the West’s relative prosperity even more obvious. Finally, Russia and its fellow Communist regimes could contemplate a series of reforms, not merely of the regular rooting-out-corruption and shaking-upthe- bureaucracy sort, but of the system itself, providing personal incentives, introducing a more realistic price mechanism, allowing increases in private farming, encouraging open discussion and entrepreneurship in dealing with the newer technologies, etc. ; in other words, going for “creeping capitalism,” such as the Hungarians were adroitly practicing in the 1970s. The difficulty of that strategy, as the Czech experiences of 1968 showed, was that “liberalization” measures threw into question the dirigiste Communist regime itself—and were therefore frowned upon by party ideologues and the military throughout the cautious Brezhnev era. 246 Reversing relative economic decline therefore had to be done carefully, which in turn made a striking success unlikely.

苏联本身的许多经济困难都能从它的卫星国的问题中反映出来——它们在20世纪50年代和60年代早期也都取得了较高的增长率,尽管同西方的水平相比仍有相当距离;也能从其卫星国强调中央计划、重工业和农业集体化这一相似的发展方针中反映出来。虽然东欧国家之间在繁荣和发展的程度上存在很大差异(而且仍在出现),但它们总的趋势都是早期突飞猛进,尔后日渐衰退,这使马克思主义的计划者们面临艰难的选择。苏联可以通过开垦荒地来增加农田,尽管北方冬季的生态环境和南方的荒漠限制了这种努力的可能性(这很容易使人想起赫鲁晓夫当年满怀信心开垦的“处女地”很快变成沙尘暴发源地)。同样,广泛地开采自然资源来解决比如石油储量与使用量不相称这类问题,也冒有效率低下的风险,因为只要矿井进入冻土区,提炼成本马上就会上升。它也可以将更多的资金投入工业和技术,但这只能以下列两种危险作代价:要么从国防中抽出人力物力资源——但是,不论领导怎么更换,国防一直是苏联第一重点;要么从消费品生产中放血——但是在通信条件的改善使西方的繁荣在东方人的眼中更加明显的情况下,这种调整的微小变化都是很不受欢迎的(特别是在东欧国家)。最后,苏联及其兄弟国家可能推行一系列改革,不仅要经常地铲除贪污、打击官僚主义,而且还要改革其体制,提供个人刺激,引入现实的价格机制,允许个体农业的发展,鼓励公开讨论和开发新技术方面的企业家精神等,就像匈牙利在20世纪70年代所巧妙实践的那样。但实施这种改革战略的困难,正如捷克斯洛伐克1968年的经验表明的那样,“自由化”措施将把控制森严的共产党政权本身置于被怀疑的危险境地,因而在十分谨慎的勃列日涅夫时代引起了党的意识形态专家和军界的不满。由此可见,要扭转经济的相对衰落必须谨慎从事,而这反过来又使得显著的成功不大可能。

Perhaps the only consolation to decision-makers in the Kremlin was that their archrival, the United States, also appeared to be encountering economic difficulties from the 1960s onward and that it was swiftly losing the relative share of the world’s wealth, production, and trade which it had possessed in 1945. Yet mention of that year is, of course, the most important fact in understanding the American relative decline. As argued above, the United States’ favorable economic position at that point in history was both unprecedented and artificial. It was on top of the world partly because of its own productive spurt, but also because of the temporary weakness of other nations. That situation would alter, against the United States, with Europe’s and Japan’s recovery of prewar level of output; and it would alter still further with the general expansion of world manufacturing production (which rose more than threefold between 1953 and 1973), since it was inconceivable that the United States could maintain its one-half share of 1945 when new factories and industrial plant were being created all over the globe. By 1953, Bairoch calculates, the American percentage had fallen to 44. 7 percent; by 1980 to 31. 5 percent; and it was still falling. 247 For much the same reason, the CIA’s economic indicators showed the United States’ share of world GNP dropping from 25. 9 percent in 1960 to 21. 5 percent in 1980 (although the dollar’s short-lived rise in the currency markets would see that share increase over the next few years). 248 The point was not that Americans were producing significantly less (except in industries generally declining in the western world), but that others were producing much more. Automobile production is perhaps the easiest way of illustrating the two trends which make up this story: in 1960, the United States manufactured 6. 65 million automobiles, which was a massive 52 percent of the world output of 12. 8 million such vehicles; by 1980, it was producing a mere 23 percent of the world output, but since the latter totaled 30 million units, the absolute American production had increased to 6. 9 million units.

也许唯一能使克里姆林宫感到安慰的是,它的主要对手美国自20世纪60年代以来也面临着经济困难,并且正在很快地失去它在1945年以来在世界财富、生产和贸易中所占有的相对比重。当然,提及这个年头对于理解美国的相对衰落具有重要意义。在历史上的这个时期,美国有利的经济地位既是空前未有的,又是不自然的。它之所以占据世界的顶峰,部分是由于它本身生产的膨胀,但也因为其他国家暂时的虚弱。随着欧洲和日本的生产恢复到战前水平,这一特殊的形势将会变得对美国不利;而且随着世界工业生产的普遍高涨(1953年到1973年增长了两倍多),形势还将进一步转化,因为新的工厂、车间在全世界普遍兴起的时候,要保持其1945年占世界工业生产的一半这个水平是不可能的。据贝尔罗克统计,到1953年,美国在全世界工业生产中所占的百分比已降到44.7%,到1980年降至31.5%,而且仍在下降。几乎由于同样的原因,美国中央情报局的经济指南也证明,美国在世界国民生产总值中所占的比重,从1960年的25.9%降到了1980年的21.5%(尽管美元在世界货币市场上短期的升值可能预示着这一比例在以后几年中会有所提高)。但这并不是说,美国的生产大大倒退了(除了那些西方世界中普遍衰落的工业部门),而是说美国以外的其他国家的生产大大地提高了。汽车生产也许是说明这一问题中两种趋势的最简单明了的例子:1960年,美国生产了665万辆汽车,占当年世界汽车产量1280万辆的52%;到了1980年,由于世界汽车总产量达到了3000万辆,尽管美国的产量增至690万辆,但它在世界总产量中所占的比重却只有23%。

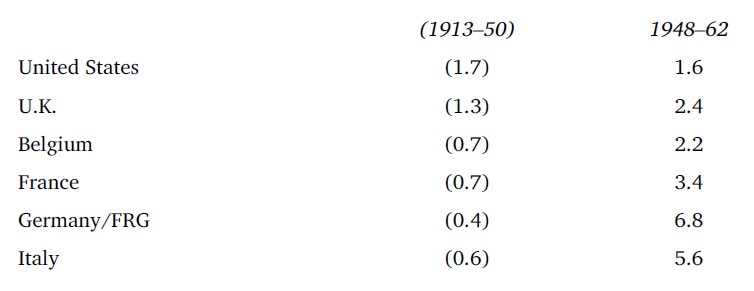

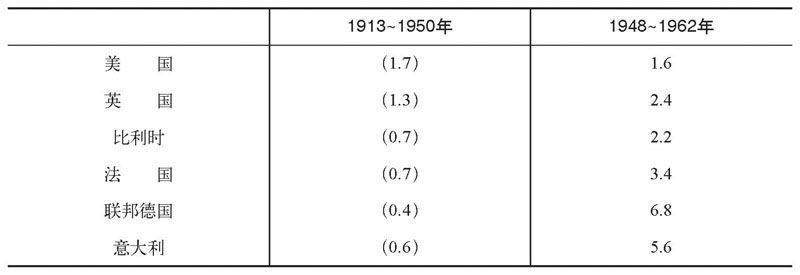

Yet despite that half-consoling thought—similar to the argument which the British used to half-console themselves seventy years earlier when their shares of world output began to be eroded—there was a worrying aspect to this development. The real question was not “Did the United States have to decline relatively?” but “Did it have to decline so fast?” For the fact was that even in the heyday of the Pax Americana, its competitive position was already being eroded by a disturbingly low average annual rate of growth of output per capita, especially as compared with previous decades (see Table 42).

虽然有这么点儿安慰——这同70年前英国面对其在世界生产中的比重开始下降,但仍习惯以此来安慰自己的情形颇为相似——但是这种变化却有令人担忧的一面。真正的问题不是“美国必然要相对衰落吗”,而是“它必然会衰落得如此之快吗”。因为即使在美国统治下的和平时期,它的竞争地位也由于每年的人均生产增长率的下降(尤其是同前几十年相比,见表42)而受到削弱。

Table 42. Average Annual Rate of Growth of Output per Capita, 1948-1962249

表42 1948~1962年人均产量每年平均增长率

Once again, it may be possible to argue that this was a historically “natural” development. As Michael Balfour remarks, for decades before 1950 the United States had increased its output faster than anyone else because it had been a major innovator in methods of standardization and mass production. As a result, it had “gone further than any other country to satisfy human needs and [was] already operating at a high level of efficiency (measured in terms of output per man per hour) so that the known possibilities for increasing output by better methods or better machinery were, in comparison with the rest of the world, smaller. ”250 Yet while that was surely true, the United States was not helped by certain other secular trends which were occurring in its economy: fiscal and taxation policies encouraged high consumption, but a low personal savings rate; investment in R&D, except for military purposes, was slowly sinking compared with other countries; and defense expenditures themselves, as a proportion of national product, were larger than anywhere else in the western bloc of nations. In addition, an increasing proportion of the American population was moving from industry to services, that is, into lowproductivity fields. 251

我们还可以说这是历史的“正常”发展。正像迈克尔·鲍尔弗所指出的,在1950年以前的几十年里,由于美国一直是标准化手段和大规模生产工艺的革新者,因此它的产量比其他任何国家都增长得快。结果是,“在满足人民的需要方面,它比其他任何国家都走得快,而且已经在高效率水平(按每小时的人均产量)上从事生产;反过来这就使美国通过采用更好的方法或更好的机械来提高产量这种司空见惯的可能性,同其他国家相比大大减少了”。然而,不管这一点多么正确,美国经济中正在发生的其他一些长期趋势仍然没有什么益处:财政和税收政策刺激了高消费,但个人储蓄率却很低;除了为军事目的进行的投资以外,对研究和开发的投资与其他国家相比正慢慢减少;而占据国民生产总值一部分的国防开支却比西方集团中的任何国家都多。另外,美国越来越多的人口正从产业部门流向服务业,即进入低产领域。

Much of this was hidden during the 1950s and 1960s by the glamour developments of American high technology (especially in the air), by the high prosperity which triggered off consumer demand for flashy cars and color televisions, and by the evident flow of dollars from the United States to poorer parts of the world, as foreign aid, or as military spending, or as investment by banks and companies. It is instructive in this regard to recall the widespread alarm in the mid-1960s at what Servan-Schreiber called le défi Américain—the vast outward surge of U. S. investments into Europe (and, by extension, elsewhere), allegedly turning those countries into economic satellites; the awe, or hatred, with which giant multinationals like Exxon and General Motors were regarded; and, associated with these trends, the respect accorded to the sophisticated management techniques imbued by American business schools. 252 From a certain economic perspective, indeed, this transfer of U. S. investment and production was an indicator of economic strength and modernity; it took advantage of lower labor costs and ensured greater access in overseas markets. Over time, however, these capital flows eventually became so strong that they began to outweigh the surpluses which Americans earned on exports of manufactures, foodstuffs, and “invisible” services. Although this increasing payments deficit did see some gold draining out of the United States by the late 1950s, most foreign governments were content to hold more dollars (that being the leading reserve currency) rather than demand payment in gold.

在20世纪50和60年代,这多种经济趋势都被下列可喜的景象所掩盖:美国高技术(特别是在空间领域)的惊人发展,刺激消费者对日新月异的汽车和彩电的消费欲望的高度繁荣,美元作为外援、军事开支或者作为银行和公司的投资从美国向世界贫困地区的转移。在这一方面,想起20世纪60年代中期谢尔温-施赖伯提出的“美国的挑战”所引起的普遍恐慌,是有启发意义的。当年所谓“美国的挑战”来自以下事实:美国大量地向欧洲(广而言之是世界各地)投资,据说要把这些国家变成自己的经济卫星国;像埃克森和通用汽车公司这样的大跨国公司引起的普遍畏惧或者憎恨;与这些趋势相联系的,还有同美国商业院校所普遍传授的先进管理技术相一致的各个方面。从某种经济观点来看,美国投资和生产的转移,的确是经济力量和现代性的证明,因为它们利用了劳动成本低廉的优势,保证其产品在海外市场畅销的广阔渠道。但是,一段时间过后,资本外流的势头变得如此强大,以至于开始超过美国通过工业制品、粮食的出口和“无形”的服务业带来的贸易盈余。尽管到20世纪50年代末期,这种日益上升的国际收支逆差已经导致美国黄金的外流,但是大多数外国政府仍然乐意持有更多的美元(成为主要的储蓄货币),而不是要求支付黄金。