China’s Balancing Act

平衡发展的中国

The competing claims of weapons modernization, the people’s social requirements, and the need to channel all available resources into “productive” nonmilitary enterprises is nowhere more pressing than in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which is simultaneously the poorest of the major Powers and probably the least well placed strategically. Yet if the PRC suffers from certain chronic hardships, its present leadership seems to be evolving a grand strategy altogether more coherent and forward-looking than that which prevails in Moscow, Washington, or Tokyo, not to mention western Europe. And while the material constraints upon China are great, they are being ameliorated by an economic expansion which, if it can be kept up, promises to transform the country within a few decades.

在实现武器装备现代化、满足人民的社会需求和将现有的资源用于非军事生产等方面,任何国家都没有中国那样急迫。中国既是大国中最穷的,同时可能也是战略地位最差的。纵然中国遭受着某种长期的困难,但看来它正在推行一种大战略。这个大战略在连续性和向前看方面,比莫斯科、华盛顿或东京的战略都强,更不用说西欧的了。物质上的困难严重地束缚着中国,但是经济的发展正使这种情况不断改善。如果经济发展能持续下去,那么这个国家将在几十年之内发生巨变。

The country’s weaknesses are so well known as to require only a brief mention here. Diplomatically and strategically, Peking has regarded itself (with some justification) as being isolated and surrounded. If this was partly due to Mao’s policies toward China’s neighbors, it was also a consequence of the rivalry and ambitions of other powers in Asia during the preceding decades. The memories of Japan’s earlier aggressions have not faded from the Chinese mind, and reinforce the caution with which the leadership in Peking regards that country’s explosive growth in recent years. Despite the 1970s thaw in relations with Washington, the United States is also viewed with some suspicion—the more particularly under a Republican regime which seems overenthusiastic about constructing an anti-Russian bloc, which appears to nourish a lingering fondness for Taiwan, and which interferes too readily against Third World countries and revolutionary movements for Peking’s liking. The future of Taiwan and the smaller offshore islands remains a thorny problem, and only half-submerged. The PRC’s relations with India have stayed cool, being complicated by their respective ties to Pakistan and Russia. Notwithstanding recent “wooing” efforts by Moscow, China feels bound to see in the USSR its chief foreign danger—and not merely because of the masses of Russian divisions and aircraft deployed along the frontier, but also in consequence of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and, more worryingly, in the military expansionism of the Soviet-supported Vietnamese state to the south. Somewhat like the Germans earlier in this century, therefore, the Chinese think deeply about “encirclement” even as they simultaneously strive to enhance their place in the global system of power. 21

中国的弱点是众所周知的,这里不必赘述。在外交和战略上,中国认为自己处于被孤立、被包围的环境之中(有一些正当理由)。如果说这部分是由于毛泽东对邻国的政策,那么它也是过去几十年其他大国在亚洲的竞争和野心所造成的。日本早年对中国的侵略并没有从中国人的记忆中消失,使中国领导人对日本近年来的爆炸性发展更持审慎态度。尽管20世纪70年代中国与美国的关系解冻了,但由于美国政府,尤其是过分热心于建立反苏联盟的共和党政府,对中国台湾表现出的恋恋不舍之情以及对中国所喜欢的第三世界国家和革命运动的过多干预,使中国对美国仍抱有一定的疑虑。中国台湾以及一些近海岛屿的前途仍然是棘手的问题,只是半掩盖着。中国与印度的关系仍然是冷淡的,并且由于它们各自与巴基斯坦以及苏联的关系而变得复杂起来。尽管近来莫斯科多次“求爱”,但中国觉得应把苏联看作它的主要外部危险,这不仅仅因为许多苏联的步兵师和大量飞机部署在中苏边界,而且还由于苏联入侵了阿富汗,而更使中国担忧的是,南边邻国越南在苏联的支持下大搞军事扩张。因此,中国人在某种程度上就像20世纪初的德国人一样,他们在努力加强自己在世界大国体系中的地位的同时,还深深感到自己处在包围之中。

Moreover, this awkward, multilateral set of diplomatic tasks has to be managed by a country which is not very strong militarily or economically, when measured against its chief rivals. For all the size of the Chinese Army in numerical terms, it remains woefully un-derequipped in modern instruments of warfare. Most of its tanks, guns, aircraft, and warships are indigenous versions of Russian or western models which China acquired years ago, and are certainly not on a par with later, much more sophisticated types; a lack of hard currency and an unwillingness to become too dependent upon other nations have kept purchases of foreign arms to a minimum. Perhaps even more worrying to Peking’s leaders are the weaknesses in China’s combat effectiveness, due to the Maoist attacks upon professionalism in the army and the preference for peasant militias—such Utopian solutions being of little assistance in the 1979 border war with Vietnam, whose battle-hardened and welltrained troops killed some 26,000 Chinese and wounded 37,000 others. 22 Economically, China appears still further behind; even when amending its official per capita GNP figures in a way which better accords with western concepts and economic measurements,23 the figure can hardly be more than a mere $500, compared with well over $13,000 for many of the advanced capitalist states and a respectable $5,000+ for the USSR. With its population likely to rise from a billion people today to 1. 2 or 1. 3 billion by the year 2000, the prospects of a major increase in personal income may not be large; even in the next century the average Chinese will be poor, relative to the inhabitants of the established Powers. Furthermore, it hardly needs saying that the difficulties of governing such a populous state, of reconciling the various factions (party, army, bureaucrats, farmers), and of achieving growth without social and ideological turbulence will test even the most flexible and intelligent leadership. China’s internal history for the past century does not offer encouraging precedents for long-term strategies of development.

不仅如此,这个国家同它的主要对手相比,无论在军事上还是在经济上都不是很强的,但它不得不去处理许多棘手的、多边的外交问题。尽管从数量上讲中国军队规模不小,但能打现代化战争的武器装备仍然少得可怜。它的大部分坦克、火炮、飞机和舰艇,都是多年以前苏联的仿制品或西方产品,当然不可与苏联或西方新近生产的先进得多的武器相匹敌。由于缺少硬通货和不愿意变得过分依赖其他国家,其外国武器的采购量一直保持在最低限度。也许更使中国领导人忧虑的是作战效能低下的问题。这是由于国家对军队专业化轻视和倚重农村民兵所造成的。在经济上,中国显得更为落后。即使按西方的概念和经济计算方法对官方公布的人均国民生产总值进行修改之后,其数字也很难超过500美元,而发达资本主义国家的人均国民生产总值已大大超过13000美元,苏联也已达到相当可观的5000美元以上。由于到2000年中国的人口可能从10亿增加到12亿或13亿,个人收入大幅度增加的可能性不大。就是到了21世纪,同现在公认的大国居民相对而言,普通中国人还是穷的。此外,无须赘言,要管理这样一个人口众多的大国,要调和各种集群(党、军队、官僚、农民)的矛盾,要取得发展而又不发生社会和意识形态的动乱,将会是困难重重的,即使对最灵活最明智的领导者而言,都将是一个考验。过去一个世纪的中国国内历史,未能向人们提供令人鼓舞的长期发展战略的先例。

Nevertheless, the indications of reform and self-improvement in China which have occurred over the past six to eight years are very remarkable, and suggest that this period of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership may one day be seen in the way that historians view Colbert’s France, or the early stages of Frederick the Great’s reign, or Japan in the post-Meiji Restoration decades: that is, as a country straining to develop its power (in all senses of that word) by every pragmatic means, balancing the desire to encourage enterprise and initiative and change with an étatiste determination to direct events so that the national goals are achieved as swiftly and smoothly as possible. Such a strategy involves the ability to see how the separate aspects of government policy relate to each other. It therefore involves a sophisticated balancing act, requiring careful judgments as to the speed at which these transformations can safely occur, the amount of resources to be allocated to longterm as opposed to short-term needs, the coordination of the state’s internal and external requirements, and—last but not least in a country which still has a “modified” Marxist system—the ways by which ideology and practice can be reconciled. Although difficulties have occurred and new ones are likely to emerge in the future, the record so far is an impressive one.

然而,中国在过去6~8年的改革和自我完善是举世瞩目的。它预示着总有一天,人们会像历史学家评价柯尔贝尔[2]的法国、腓特烈大帝[3]执政的早期普鲁士或明治维新后几十年复兴时期的日本那样,把邓小平领导下这一时期的中国看作是一个正使用各种有效手段努力增强本国国力(所有意义上的国力)的国家,它正在平衡人们的欲望,激励进取心、开创精神和变革勇气,以国家干预主义的决心去指点江山,以便尽快地顺利实现国家目标。实行这样的战略,需要有洞察政府政策各个不同方面的相互关系的能力,需要进行复杂的协调工作,并要对下列几个方面做出周密的判断:顺利实行变革的速度,依据近期与长远需要分配资源,协调国内和国外需求,意识形态和实践之间相互适应——这是最后一个但并非最不重要的一个方面,因为中国有一个“改进了”的马克思主义体系。虽然已经遇到了不少困难,而且将来还会出现新的困难,但是到目前为止,成就是显而易见的。

It can be seen, for example, in the many ways in which the Chinese armed services are transforming themselves after the convulsions of the 1960s. The planned reduction of the People’s Liberation Army (which includes the navy and air force) from 4. 2 to 3 million personnel is, in fact, an enhancement of real strength, since far too many of them were merely support troops, used for railway-building and civic duties. Those remaining within the armed forces are likely to be of higher overall quality: new uniforms and the restoration of military ranks (abolished by Mao as being “bourgeois”) are the outward sign of this; but they will be reinforced by replacing a largely volunteer army with conscription (to give the state access to high-quality personnel), by reorganizing the military regions and streamlining the staffs, and by improving officer training at the academies, which have also emerged from their period of Maoist disgrace. 24 Along with this will go a large-scale modernization of China’s weaponry, which, although numerically substantial, suffers from considerable obsolescence. Its navy is being given an array of new vessels, from destroyers and escorts to fast-attack craft and even hovercraft; and it has built up a very substantial fleet of conventional submarines (107 in 1985), making it the third-largest such force in the world. Its tanks are now displaying laser rangefinders; its aircraft are becoming all-weather types, with modern radar. All this is attended by a willingness to experiment with large-scale maneuvers under modern battlefield conditions (one such 1981 maneuver involved six or seven Chinese armies backed by aircraft—which had been missing in the 1979 clash with Vietnam),25 and to rethink the strategy of a “forward defense” along the frontiers with Russia in favor of counterattacks some way behind the long, exposed borders. The navy, too, is experimenting on a much larger scale: in 1980 an eighteen-vessel task force undertook an eight-thousand-nautical-mile mission in the South Pacific, in conjunction with China’s latest intercontinental ballistic missile experiments. (Was this, one wonders, the first significant demonstration of Chinese sea power since Cheng Ho’s cruises of the early fifteenth century? See pp. 6–7 above. )

例如,众所周知,中国军队在60年代的社会动荡之后实行了一系列改革。中国人民解放军(包括海军和空军)有计划地将其员额从420万裁减到300万,实际上是增强了实力,因为裁减的员额中,许多人都是支援部队,用于修建铁路和民用工程。保留下来的可能是各方面素质比较好的武装部队,换发新的军服和恢复军衔制,是它的外部象征。这支部队还由于采取下列措施而得到增强:用义务兵代替大量的志愿兵,使国家能得到高质量的人员;改组大军区和精简机构;改进军事院校的教育。随之到来的将是大规模的武器装备现代化。中国的武器装备虽然数量很多,但相当一部分是过时的。它的海军已经(正在)装备包括从驱逐舰、护卫舰到快艇的一系列舰艇,甚至还有气垫船。这支海军还建立了一支很大的常规潜艇部队(1985年有107艘潜艇),这是世界上第三大的潜艇部队。中国军队的坦克现在装备了激光测距仪,飞机正改装为配有现代化雷达的全天候型。所有这些,都是为了适应现代战争条件下的大规模机动作战(1981年曾进行过一次有6或7个军参加的、有飞机支援的演习——但在1979年同越南的冲突中飞机没有出现),和重新考虑在中苏边界实行“前沿防御”的战略,以利于在漫长的暴露的边界之后实施反突击。海军也进行了规模比以往大得多的演习:为配合中国最新的一次洲际弹道导弹试验,1980年由18艘舰艇组成的特混编队远航8000海里到南太平洋执行任务。(人们惊叹,这不是15世纪初郑和远航以后中国海上力量第一次有意义的远航吗?)

More impressive still, for China’s emergence as a Great Power militarily, has been the extraordinarily rapid development of its nuclear technology. Although the first Chinese tests occurred in Mao’s time, he had publicly scorned nuclear weapons when preferring the merits of a “people’s war”; the Deng leadership, by contrast, is intent upon taking China into the ranks of the modern military states as swiftly as possible. As early as 1980, China was testing ICBMs with a range of seven thousand nautical miles (which would encompass not only all of the USSR but also parts of the United States). 26 A year later, one of its rockets launched three space satellites, which is an indication of a multiple-warhead rocket technology. Most of China’s nuclear forces are land-based, and medium-range rather than long-distance; but they are being joined by new ICBMs and, perhaps the most significant step of all (in terms of nuclear deterrence), by a fleet of missile-carrying submarines. Since 1982, China has been testing submarine-launched ballistic missiles and working on improvements of both range and accuracy. There are also reports of Chinese experimentation with tactical nuclear weapons. All this is backed up by large-scale atomic research, and by a refusal to have its nuclear weapons development “frozen” by international limitations agreements, since that would merely aid the existing Great Powers.

中国作为一个崭露头角的军事大国,给人印象更为深刻的是它以异乎寻常的速度发展的核技术。中国的第一次核试验是在毛泽东时代,但毛泽东本人在赞扬“人民战争”的作用时曾经公开藐视核武器。而以邓小平为首的中国领导层则坚决要使中国尽快跻身于现代化的军事国家之林。早在1980年,中国就试验了射程7000海里的洲际弹道导弹(这一射程不但可以覆盖苏联全境,而且可以攻击到美国的一部分地区)。一年之后,中国的一枚火箭发射了3颗卫星,这表明中国掌握了多弹头火箭技术。中国的大部分核武器是陆基的,而且是中程而非远程的,但是新的洲际弹道导弹正在加入这一行列。也许意义最为重大的是一支携带导弹的潜艇部队(从核威慑的意义上讲)。自1982年以来,中国一直在试验潜射弹道导弹,并不断提高其射程和命中精度。也有报道说中国正在试验战术核武器。所有这些都得益于中国大规模的原子研究和拒绝接受国际核禁试条约、对原子武器开发实行“冻结”的立场,因为这种约束只对现有的核大国有利。

As against this evidence of military-technological prowess, it is also easy to point to continuing signs of weakness. There is always a significant time lag between producing an early prototype of a weapon and having large numbers of them, tried and tested, in the possession of the armed forces themselves; and this is particularly so with a country which is not rich in capital or scientific resources. Severe setbacks —including the possible explosion of a Chinese submarine while attempting to launch a missile; the cancellation or slowdown of weapons programs; the lack of expertise in metallic technology, advanced jet engines, and radar, navigation, and communications equipment—continue to hamper China’s drive toward real military equality with the USSR and the United States. Its navy, despite the Pacific Ocean exercises, is far from being a “blue water” fleet, and its force of missile-bearing submarines will long remain behind those of the “Big Two,” which are pouring funds into the development of gigantic types (Ohio class, Alfa class) that can dive deeper and run faster than any previous submarine. 27 Finally, the mention of finance is a reminder that as long as China is spending only one-eighth or thereabouts of the amount upon defense as the superpowers, there is no way it can achieve full parity; it cannot, therefore, plan to acquire every sort of weapon or to prepare for every conceivable threat.

虽然中国在军事技术方面取得了这些成就,但也不难指出它仍然存在着的弱点。从研制出一种原型武器到大量生产、试验和测试,最后装备部队,这中间的时间拖得太长。在一个资金和资源都不富裕的国家,情况更是如此。一些严重的问题,包括在试验潜射导弹时可能发生的爆炸,撤销或推迟武器研制计划,缺乏合金冶炼以及先进的喷气发动机、雷达、导航和通信设备制造等方面的专门技术等,继续妨碍着中国在军事上真正取得同美苏并驾齐驱的地位。它的海军,虽然进行过太平洋演习,但还远不是一支远洋海军,它的导弹潜艇部队在今后很长的时期内仍将落后于“两强”。它们正把大量资金投入发展比现有潜艇下潜更深、航行得更快的巨型潜艇(“俄亥俄”级和“阿尔法”级)。最后是财政问题。中国向人们预示:只要中国的国防费用只相当于或大约相当于超级大国国防开支的1/8,它就不可能完全达到势均力敌,因此也就不可能得到各种武器或做好对付各种可能的威胁的准备。

Nonetheless, even China’s existing military capability gives it an influence which is far more substantial than that existing some years ago. The improvements in training, organization, and equipment ought to place the PLA in a better position to meet regional rivals like Vietnam, Taiwan, and India than in the past two decades. Even the military balance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union may no longer be so disproportionately tilted in Moscow’s favor. Should future disputes in Asia lead to a Sino-Russian war, the leadership in Moscow may find it politically difficult to consent to launching heavy nuclear strikes at China, both because of world reaction and because of the unpredictability of the American response; but if it did “go nuclear,” there is less and less prospect of the Soviet armed forces being able to guarantee the destruction of China’s growing land-based and (especially) sea-based missile systems before they can retaliate. On the other hand, if there is only conventional fighting, the Soviet dilemma remains acute. The fact that Moscow takes the possibility of war seriously can be gleamed from its deployment of around fifty divisions (including six or seven tank divisions) of Russian troops in its two military districts east of the Urals. And while it may be assumed that such forces can handle the seventy or more PLA divisions similarly stationed in the frontier area, their superiority may hardly be enough to ensure a striking victory—especially if the Chinese trade space for time in order to weaken the effects of a Soviet Blitzkrieg. To many observers, there now exists a “rough equivalence,” a “balance of forces,” in Central Asia28— and, if true, the strategical repercussions of that extend far beyond the immediate region of Mongolia.

然而,就是目前的军事能力,也使中国具有比几年前大得多的影响。训练、编制和装备的改善,使中国在对付地区性对手(如越南、中国台湾以及印度)方面处于比过去20年好得多的地位。就是同苏联相比,军事优势也不再是那么不合比例地偏到苏联一方。在将来,如果亚洲的冲突导致中苏战争,莫斯科的领导者们将发现,他们在政治上很难做出对中国实施沉重核打击的决定,这不仅仅因为世界人民的反对以及美国的反应无法预测,还因为如果它真的“使用核武器”,它的军队确保彻底摧毁中国日益强大的陆基尤其是海基导弹、使中国丧失报复能力的前景也越来越暗淡。在另一种情况下,如果只是打常规战争,苏联同样处于极其窘迫的境地。从苏联把约50个师(包括六七个坦克师)的部队部署于乌拉尔以东的两个军区这一事实可以看出,莫斯科对发生战争的可能性是认真对待的。尽管可以设想,苏联的这些部队能够对付人民解放军相应部署在边境地区的70个或更多的师,但是它们的军事优势还远远不足以保证进攻的胜利,尤其在中国人采取以空间换取时间的打法来削弱苏军的快速打击效果时更是如此。许多观察家认为,中亚存在“大致相等”的态势或者“力量均势”,如果情形真是这样,那么它在战略上产生的影响会大大超越邻近的蒙古地区。

But the most significant aspect of China’s longer-term war-fighting power lies elsewhere: in the remarkably swift growth of its economy which has occurred during the past few decades and which seems likely to continue into the future. As was mentioned in the preceding chapter (see pp. 418–20), even before the Communists had firmly established their rule, China was a considerable manufacturing power—although that was disguised by the sheer size of the country, the fact that the vast majority of the population consisted of peasant farmers, and the disruptions of war and civil wars. The creation of a Marxist regime and the coming of domestic peace allowed production to shoot ahead, with the state actively encouraging both agricultural and industrial growth—although sometimes doing so (i. e. , under Mao) by bizarre and counterproductive means. Writing in 1983–1984, one observer noted that “China has achieved annual growth rates in industry and agriculture since 1952 of around 10 percent and 3 percent respectively, and an overall growth of GNP of 5–6 percent per year. ”29 If those figures do not match the achievements of such export-oriented Asian “trading states” as Singapore or Taiwan, they are impressive for a country as large and populous as China, and readily translate into an economic power of some size. By the late 1970s, according to one calculation, the Chinese industrial economy was as large as (if not larger than) those of the USSR and Japan in 1961. 30 Moreover, it is worth remarking once again that these average growth rates include the period of the so-called Great Leap Forward of 1958–1959; the break with Russia, and the withdrawal of Soviet funds, scientists, and blueprints in the early 1960s; and the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, which not only distorted industrial planning but also undermined the entire educational and scientific system for nearly one generation. Had those events not occurred, Chinese growth would have been even faster overall—as may be gathered from the fact that over the past five years of Deng-led reforms, agriculture has averaged an 8 percent growth, and industry a spectacular 12 percent. 31

但是,中国更长远的作战能力中最有意义的方面不在这里,而在于它引人注目地飞速发展的经济。这样的发展速度已有多年了,看来将来还会保持下去。就像前面一章所说的,在共产党建立牢固的政权之前,中国已是一个重要的制造业国家;但这一点被广袤的国土、农民占人口的绝大多数以及战争和内战的破坏掩盖起来了。马克思主义政权的建立和国内和平的到来,以及国家积极采取促进工农业发展的措施(尽管在毛泽东时代有时采取的措施是奇怪的和违反生产力的),使生产得到了迅速发展。一位观察家在1983~1984年写道:“自1952年以来,中国工业和农业的年增长率分别为10%和3%左右,国民生产总值的年平均增长率为5%~6%。”虽然那些数字不能与新加坡或中国台湾这类出口导向的亚洲“贸易地区”的成绩相比拟,但是对于中国这样一个幅员辽阔、人口众多的大国来说,这个增长速度是令人难忘的,而且会使它很快转变为一个相当规模的经济大国。据估计,到20世纪70年代末,中国工业经济的规模已相当于(如果不是超过的话)苏联和日本1961年的规模。此外,值得再提一下的是,上述平均增长率的计算包括了下列时期的数字:1958~1959年的所谓“大跃进”时期;与苏联关系破裂,苏联撤回资金、科技人员和工程图纸的60年代初期;以及不但工业生产计划受冲击,而且几乎一代人的教育和科研体制遭破坏的“文化大革命”时期。如果不发生那些事态,中国经济的综合增长速度会快得多——这可以从下面的事实得到证明:在邓小平领导下进行改革的过去5年中,农业的年平均增长速度为8%,工业为惊人的12%。

To a very large degree, the agricultural sector remains both China’s opportunity and its weak point. The East Asian methods of wet-rice cultivation are inordinately productive in yields per hectare, but are also extremely labor-intensive—which makes it difficult to effect a switch to, say, the large-scale, mechanized forms of agriculture used on the American prairies. Yet since agriculture forms over 30 percent of China’s GDP and employs 70 percent of the population, decay (or merely a slowdown) in that sector will act as a drag upon the entire economy—as has clearly happened in the Soviet Union. This challenge is compounded by the population time bomb. Already China is attempting to feed a billion people on only 250 million acres of arable land (compared with the United States’ 400 million acres of crops for its 230 million population);32 can it possibly manage to feed another 200 million Chinese by the year 2000, without an increasing dependence upon imported food, which has both balance-of-payments and strategic costs? It is difficult to get a clear answer to that crucial question, in part because the experts point to different pieces of evidence. China’s traditional export of foodstuffs slowly declined over the past three decades, and in 1980 it became, very briefly, a net importer. 33 On the other hand, the Chinese government is devoting massive scientific resources into achieving a “green revolution” on the Indian model, and Deng’s encouragement of market-oriented reforms, together with large increases in agricultural purchase prices (without passing the cost on to the cities), have led to tremendous rises in food production over the past half-decade. Between 1979 and 1983—when much of the rest of the globe was suffering from economic depression —the 800 million Chinese in rural areas increased their incomes by about 70 percent, and their calorific intake was nearly as high as that of Brazilians or Malaysians. “In 1985, the Chinese produced 100 million more tons of grain than they did a decade earlier, one of the most productive surges ever recorded. ”34 With the population increasing, and turning more and more to meat consumption (which requires yet more grain), the pressure to keep up this expansion in agricultural consumption will become more intense—and yet the acreage available remains restricted, and the growth in yields caused by the applications of fertilizer is bound to slow down. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that China is managing to maintain this part of its elaborate balancing act with a considerable degree of success.

在很大程度上,农业部门仍然既是中国的机遇所在,也是它的薄弱环节。东亚的水稻种植方法使每公顷的产量很高,但劳动强度也很高,很难转变为实行美国平原地区的那种大规模机械化农业生产。然而,由于农业占中国国民生产总值的30%,农业的衰退(或仅是发展缓慢),就会像人们从苏联清楚看到的那样,阻碍整个经济的发展。这种挑战和人口这颗定时炸弹结合到一起了。中国已在设法依靠它那只有2.5亿英亩的可耕地来养活10亿人口(而美国则是4亿英亩农田,2.3亿人口)。到2000年,中国人口将再增加2亿,它能不增加对进口粮食的依赖而解决人民的吃饭问题吗(进口粮食有一个收支平衡问题和战略消耗问题)?对于这个关键性的问题,要做出明确的回答是很难的,其中部分原因是专家们的看法不同。在过去30年中,中国的食品出口逐步下降,到1980年成了一个地道的纯进口国。而另一方面,中国政府仿效印度的做法,投入大量的科技力量去搞“绿色革命”,加之邓小平提倡进行发展市场经济的改革和大幅度提高农产品的收购价格(不把提价造成的负担转嫁给城市),已使过去5年的粮食产量大幅度增加。1979~1983年,就在世界的大部分地区出现经济衰退之时,8亿中国农民的收入却增加了70%,他们的热量日摄入量和巴西人或马来西亚人几乎一样。“1985年,中国人生产的粮食比10年前增加了1亿多吨,创造了历史最高产量。”随着人口的增长和肉类消费的增加,粮食生产也要不断提高以满足需要(谷物需求量更大)。保持农业消费品急剧增长的压力将变得越来越大,而可耕地面积仍然有限,靠使用化肥来提高的产量肯定会逐渐下降。然而,事实表明,中国正在设法继续精心地做好这方面的协调工作,并且取得了相当的成功。

The future of China’s drive toward industrialization is of even greater importance —but is a yet more delicate trick internally. It has been hampered not only by the lack of consumer purchasing power, but also by years of rather heavy-handed planning on the Russian and eastern European model. The “liberalization” measures of the past few years—getting state industries to respond to the commercial realities of quality, price, and market demand, encouraging the creation of privately run, small-scale enterprises, and allowing a great expansion in foreign trade35—have led to impressive rises in manufacturing output, but also to many problems. The creation of tens of thousands of private businesses has alarmed party ideologists, and the rise in prices (probably caused as much by the necessary adjustment to market costs as by the frequently denounced “racketeering” and “profiteering”) has caused mutterings among urban workers, whose incomes have not risen as fast as either the farmers’ or the entrepreneurs’. In addition, the foreign-trade boom quickly led to a sucking in of imported manufactures, and thus to a trade deficit. The statements made in 1986 by Prime Minister Zhao Ziyang that matters may have slipped somewhat “out of control” and that “consolidation” was needed for a while —together with the announced decrease in the hectic growth targets—are indications that internal and ideological problems remain. 36

中国为实现工业化而奋斗的前景更具重要性,但在国内,这也是一个更为棘手的问题。它不但受阻于消费者购买力低,也受阻于多少年来采用的苏联-东欧模式这样僵化的计划经济。过去几年采取的市场化措施——让国营企业依据质量、价格和市场需求等商业行情组织生产,鼓励建立私营和小型企业,允许扩大对外贸易等,已使工业产品的产量大大提高,但同时也带来了许多问题。成千上万个个体商贩的出现,使中国共产党的意识形态工作者遇到了许多难题。物价上涨(可能是经常受到谴责的投机商造成的,也可能是按照市场价格进行必要的调整造成的),使城市工人很不满意,因为他们的收入既不如农民也不如企业家增长得快。另外,外贸的急剧发展,也导致进口过多,造成贸易逆差。1986年的决策层曾表示,事态的发展有些“失控”,有必要“整顿”一下,包括落实曾经宣布过的降低由于头脑过热而制定的增长指标。这些话表明,内部和思想上还存在问题。

It is nevertheless remarkable that even the reduced growth rates are planned to be a very respectable 7. 5 percent annually in future years (as opposed to the 10 percent rate since 1981). That itself would double China’s GNP in less than ten years (a 10 percent rate would do the same in a mere seven years), yet for a number of reasons economic experts seem to feel that such a target can be achieved. In the first place, China’s rate of savings and investment has been consistently in excess of 30 percent of GNP since 1970, and while that in turn brings problems (it reduces the proportion available for consumption, which is compensated for by price stability and income equality, which in turn get in the way of entrepreneur ship), it also means that there are large funds available for productive investment. Secondly, there are huge opportunities for cost savings: China has been among the most profligate and extravagant countries in its consumption of energy (which caused declines in its quite considerable oil stocks), but its post-1978 energy reforms have substantially reduced the costs of one of industry’s main “inputs” and thus freed money for investments elsewhere—or consumption. 37 Moreover, only now is China beginning to shake off the consequences of the Cultural Revolution. After more than a decade during which Chinese universities and research institutes were closed (or compelled to operate in a totally counterproductive way), it was predictable that it would take some time to catch up on the scientific and technological progress made elsewhere. “It is only against this background,” it was remarked a few years ago, that one can understand the importance of the thousands of scientists who went to the United States and elsewhere in the West in the late 1970s for stays of one or two years and occasionally longer periods. … as early as 1985—and certainly by 1990—China will have a cadre of many thousands of scientists and technicians familiar with the frontiers of their various fields. Tens of thousands more trained at home as well as abroad will staff the institutes and enterprises that will implement the programs required to bring Chinese industrial technology up to the best international standards, at least in strategic areas of activity. 38

然而,值得注意的是,降低了的增长率,在这之后几年中,还是非常可观的7.5%(1981年后曾是10%)。这本身就将使中国的国民生产总值在不到10年的时间里翻一番(如果是10%,只要7年就可以做到)。由于以下一些原因,经济学家们认为,这个目标是可以达到的。首先,自1970年以来,中国的积累和投资一直超过国民生产总值的30%。而这同时也带来了一些问题。它使消费资金减少了,这虽然从物价稳定、收入平均得到补偿,但给企业家设置了障碍。它也意味着,还有大量资金可用于生产投资。其次,在降低成本方面还大有潜力可挖。在能源消耗方面,中国是浪费惊人的国家之一,这导致它相当丰富的石油储量下降。但1978年之后实行的能源制度改革,极大地降低了其工业主要“投入”的成本,从而省下资金,用于其他项目或消费方面的投资。最后,当时中国才刚刚开始消除“文化大革命”的影响。在长达10多年的时间里,中国的大学和研究机构曾经被关闭(或被迫完全违背生产力发展规律行事)。可以预料,在这之后,需要时间来赶上世界科技的进步。几年前帕金斯在其《国际影响》一书中这样写道: 只有知道这个背景,人们才能认识到70年代后期数以千计的科技人员到美国或其他西方国家待上一两年或者更长时间的重要性……最早到1985年——当然到1990年就更是如此——中国就将有一支数千人的熟悉本行尖端技术的科技干部队伍。成千上万名在国内外受过培训的科技人员将被分配到各科研机构或企业。这些机构和企业将具体落实旨在把中国的工业技术水平,至少是战略领域的技术水平,提高到国际最高水平的计划。

In the same way, it could only be in the post-1978 period of encouraging (albeit selectively) foreign trade and investment in China that its managers and entrepreneurs had the proper opportunity to pick and choose from among the technological devices, patents, and production facilities enthusiastically offered by western governments and companies which quite exaggerated the size of the Chinese market for such items. Despite—or, rather, because of—the Peking government’s desire to control the level and contents of overseas trade, it is likely that imports will be deliberately selected to boost economic growth.

同样,也只有在1978年之后鼓励(当然是有选择地)发展对外贸易和吸引外资的时期,中国的经理和企业家们才有适当的机会从西方政府和公司热情提供的仪器、专利和生产设备中选取最合适的东西。而西方政府和公司夸大了他们的产品在中国的市场。或者更确切地说,由于中国政府要控制对外贸易的数额和项目,对进口可能要作精心选择,使之起到促进经济发展的作用。

The final and perhaps the most remarkable aspect of China’s “dash for growth” has been the very firm control upon defense spending, so that the armed forces do not consume resources needed elsewhere. In Deng’s view, defense has to remain the fourth of China’s much-vaunted “four modernizations”—behind agriculture, industry, and science; and although it is difficult to gain exact figures on Chinese defense spending (chiefly because of different methods of calculation),39 it seems clear that the proportion of GNP allocated to the armed forces has been tumbling for the past fifteen years—from perhaps 17. 4 percent in 1971 (according to one source) to 7. 5 percent in 1985. 40 This in its turn may cause grumbling among the military and thus increase the internal debate over economic priorities and policies; and it would clearly have to be reversed if serious border clashes recurred in the north or the south. Nonetheless, the fact that defense spending must take an inferior place is probably the most significant indication to date of China’s all-out commitment to economic growth, and stands in stark contrast to both the Soviet obsession with “military security” and the Reagan administration’s commitment to pouring funds into the armed services. As many experts have pointed out,41 given China’s existing GNP and amount of national savings and investment within it, there would be no real problem in spending much more than its current c. $30 billion on defense. That it chooses not to do so reflects Peking’s belief that long-term security will be assured only when its present output and wealth have been multiplied many times.

最后一个措施,也许是中国为迅速发展经济而采取的最引人注目的措施,即严格控制国防开支,使军队不能消耗可用于其他方面的资源。按照邓小平的观点,国防必须排在中国大力宣传的“四个现代化”的第四位,即排在农业、工业和科技之后。虽然要得到中国国防开支的准确数字是很困难的(这主要是由于计算方法的不同),但看来,这种费用已从15年前(1971年)占国民生产总值的17.4%,骤降到1985年的7.5%。这可能会在军队中引起抱怨,并使国内关于经济发展先后顺序和经济政策的争论更加激烈。如果北方或南方发生严重的边界冲突,可能不得不改变这种方针。然而,把国防开支放在次要的地位,是中国全力发展经济的决心的最有说服力的例证。它与苏联拼命追求“军事安全”的思想以及里根政府把大量资金投入武装部队建设的许诺形成了鲜明的对照。正如许多专家指出的,依据中国目前的国民生产总值(包括国家积蓄和投资),中国在国防上的花费比目前的大约300亿美元更多一些是没有问题的。但中国没有这样做。这反映了中国这样的信念:只有在目前的产量和财富翻了好几番之后,长期的安全才有保障。

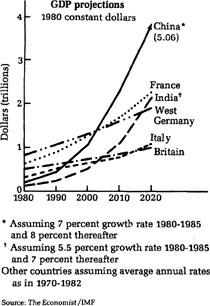

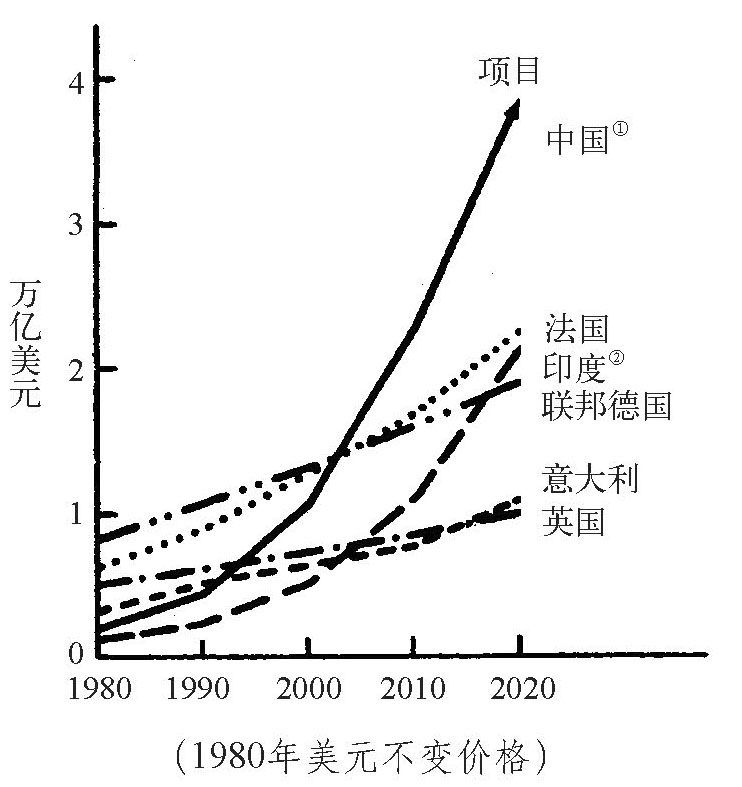

In sum: “The only events likely to stop this growth in its tracks would be the outbreak of war with the Soviet Union or prolonged political upheaval on the pattern of the Cultural Revolution. China’s management, energy, and agricultural problems are serious, but they are the kinds of problems faced and overcome by all developing nations during the growth process. ”42 If that seems a remarkably rosy statement, it pales compared with The Economist’s recent calculation that if China maintains an average 8 percent annual growth—which it calls “feasible”—it would soar past the British and Italian GNP totals well before 2000 and be vastly in excess of any European power by 2020. 43

总而言之,只有爆发中苏战争或发生像“文化大革命”那样长期的政治动乱,才可能阻止中国沿着自己的道路发展。中国在管理、能源和农业方面的问题是严重的,但这些是所有发展中国家在其发展过程中都曾遇到过和解决过的问题。如果说,这显然是一种乐观的说法,那么它和《经济学人》杂志所做的估计相比,就算不上什么了。据《经济学人》杂志估算,如果中国经济保持被称为“可以做得到的”8%的年增长率,那么不用到2000年,它的国民生产总值就可以大大超过英国和意大利,到2020年可以超过欧洲任何一个大国(参见图2)。

Chart 2. GDP Projections of China, India, and Certain Western European States, 1980–2020

图2 中国、印度和某些西欧国家1980~2020年的国内生产总值预测

①假定1980~1985年间的年增长率为7%,此后为8%。②假定1980~1985年间的年增长率为5.5%,此后为7%。其他国家的年增长率,假定保持1970~1982年间的水平。资料来源:《经济学人》/国际货币资金组织

The greatest mistake of all would be to assume that this sort of projection, with all the changeable factors that it rests upon, could ever work out with such exactitude. But the general point remains: China will have a very large GNP within a relatively short space of time, barring some major catastrophe; and while it will still be relatively poor in per capita terms, it will be decidedly richer than it is today.

由于这类预测包括许多可变因素,因此设想据此做出的预测将十分准确,那将是极其错误的。但总的发展趋势是,在一段比较短的时间内,如不发生大的灾难,中国的国民生产总值将达到很大的数字。虽然那时它的人均国民生产总值仍然很少,但它肯定要比现在富有得多。

Three further points are worth making about China’s future impact upon the international scene. The first, and least important for our purposes, is that while the country’s economic growth will boost its foreign trade, it is impossible to transform it into another West Germany or Japan. The sheer size of the domestic market of a continent-wide Power such as China, and of its population and raw-materials base, makes it highly unlikely that it would become as dependent upon overseas commerce as one of the smaller, maritime “trading states. ”44 The extent of its laborintensive agricultural sector and the regime’s determination not to become too reliant upon imported foodstuffs will also be a drag upon foreign trade. What is likely is that China will become an increasingly important producer of low-cost goods, like textiles, which will help to pay for western—or even Russian— technology; but Peking is clearly determined not to become dependent upon foreign capital, manufactures, or markets, or upon any one country or supplier in particular. Acquiring foreign technology, tools, and production methods will all be subject to the larger requirements of China’s balancing act. This is not contradicted by China’s recent membership in the World Bank and the IMF (and its possible future membership in GATT and the Asian Development Bank)—which are not so much indications of Peking’s joining the “free world” as they are of its hard-nosed calculation that it may be better to gain access to foreign markets, and to long-term loans, via international bodies than through unilateral “deals” with a Great Power or private banks. In other words, such moves protect China’s status and independence. The second point is separate from, but interrelates with, the first. It is that whereas in the 1960s Mao’s regime seemed almost to relish the frequent border clashes, Peking now prefers to maintain peaceful relations with its neighbors, even those it regards with suspicion. As noted above, peace is central to Deng’s economic strategy; war, even of a regional sort, would divert resources into the armed services and alter the order of priority among China’s “four modernizations. ” It may also be the case, as has been argued recently,45 that China feels more relaxed about relations with Moscow simply because its own military improvements have created a rough equilibrium in central Asia. Having achieved a “correlation of forces,” or at least a decent defensive capacity, China can concentrate more upon economic development.

未来的中国对世界的影响,有三点值得一提。第一点,也是对于我们来讲最不重要的一点,是中国在发展经济的同时,也会增加它的对外贸易。但在这方面,中国不会成为第二个联邦德国或日本。像中国这样一个幅员辽阔的大国,它的国内市场广大,人口众多,原材料丰富,它不会变得像国土较小的海上“贸易国家”那样依赖于海外商业。它那劳动密集型农业部门的规模,以及政府的不愿变得过于依赖粮食进口的决心,也将阻碍对外贸易的迅速发展。但中国很可能成为重要的低成本产品(例如纺织品)生产国,这将使中国有能力支付引进西方甚至是苏联技术的费用。但中国的决心很清楚,它要使中国不依赖于外国资本、外国工业品和外国市场,也不依赖于某一国家尤是某一供应国。引进外国技术、设备和生产方法,都必须服从中国收支平衡这一大局的要求。这与中国成为世界银行和国际货币基金组织成员并不矛盾,并且它还可能成为关税与贸易总协定和亚洲发展银行的成员。但这并不表明中国要加入“自由世界”,而这恰恰是中国的精明所在:这样它就可以更容易地进入外国市场,通过国际组织而不是通过某一大国或私人银行的双边“交易”,取得长期贷款。换句话说,这样的做法维护了中国的尊严和独立。第二点与第一点不同但有关联,那就是中国更愿意与它的邻国——哪怕是它怀有疑虑的邻国保持和平关系。如上所述,和平是邓小平的经济战略的核心;战争,哪怕是局部战争,也会导致把资源转移到满足军队需要方面,从而打乱中国“四个现代化”的先后顺序。情况也可能像人们所说的那样,中国对中苏关系感到更放心了,因为它的军队状况有了改善,造成了中亚地区的大致均势。由于有军事力量作保障,或者说由于有了像样的防御能力,中国可以更加集中精力去发展经济了。

Yet if its intentions are peaceable, China also emphasizes how determined it is to preserve its own complete independence, and how much it disapproves of the two superpowers’ military interventions abroad. Even toward Japan the Chinese have kept a wary eye, restricting its share of the import/export trade and yet also warning Tokyo not to get too heavily involved in developing Siberia. 46 Toward Washington and Moscow, China has been much more studied—and critical. All of the Soviet suggestions for improving relations and even the return of Soviet engineers and scientists to China in early 1986 have not altered Peking’s fundamental position: that a real improvement cannot take place until Moscow makes concessions in some, if not all, of the three outstanding issues—the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, the Russian support of Vietnam, and the long-standing question of central Asian boundaries and security. 47 On the other hand, U. S. policies in Latin America and the Middle East have come in for repeated attack from Peking (as, to be sure, have similar Russian adventures in the tropics). Being economically one of the “less-developed countries” and inherently suspicious of the white races’ domination of the globe makes China a natural critic of superpower intervention, even if it is not a formal member of the Third World movement and even if those criticisms are nowadays fairly mild compared to Mao’s fulminations of the 1960s. And despite its earlier (and still powerful) hostility to Russian pretensions in Asia, the Chinese remain suspicious of the earnest American discussion of how and when to play the “China card. ”48 In Peking’s view, it may be necessary to incline toward Russia or (more frequently, since the Sino-Soviet quarrels) toward the United States, by measures including the joint monitoring of Russian nuclear testing and exchanging information over Afghanistan and Vietnam; but the ideal position is to be equidistant between the two, and to have them both wooing the Middle Kingdom.

虽然中国有和平的诚意,但它也强调决心维护自己的完全独立,不赞成两个超级大国对外国的干涉。即便是对日本,中国也一直怀有戒心,限制对日进出口贸易的比例,并警告日本不要太多地参与开发西伯利亚。对美国和苏联,中国的态度更为谨慎,并且是批判性的。苏联关于改善两国关系的所有建议,甚至是1986年初苏联提出的苏联工程技术人员重返中国的建议,都不能动摇中国的基本立场:如果苏联在消除三大障碍——苏联入侵阿富汗、苏联支持越南和长期以来的中亚边境安全问题——方面不做出让步(尽管不是彻底的),中苏关系就不可能改善。另一方面,美国对拉丁美洲和中东的政策遭到中国的反复抨击(就像苏联在热带地区的冒险遭到抨击一样)。尽管它今天的抨击比20世纪60年代毛泽东的怒斥温和一些,但在经济上是“发展中国家”之一及其对白色人种控制全球的固有戒心,使中国成为超级大国的干涉行为的天然批评者。尽管中国早就对苏联在亚洲的意图抱敌对态度,中国对同美国真诚地讨论如何及何时打“中国牌”仍持怀疑态度。在中国看来,可能有必要倾向苏联,或(因为中苏不和,更经常的是)倾向美国,这正通过共同监视苏联的核试验、交换有关阿富汗和越南的情报等措施表现出来;但最好是与美苏保持等距离,使它们都向中国“求爱”。

To this extent, China’s importance as a truly independent actor in the present (and future) international system is enhanced by what, for want of a better word, one might term its “style” of relating to the other Powers. This has been put so nicely by Jonathan Pollack that it is worth repeating in extenso:

从这个意义上讲,中国在当前(和将来)的国际体系中作为真正独立的角色的重要性,由于它在处理与其他大国的关系时所表现出的“风格”(由于没有更好的词,姑且用“风格”吧)而大大增强了。对于这一点,乔纳森·波拉克描述得再好不过了,因此,有必要把他的话大段地摘录于下:

[W]eapons, economic strength, and power potential alone cannot explain the imputed significance of China in a global power equation. If its strategic significance is judged modest and its economic performance has been at best mixed, this cannot account for the considerable importance of China in the calculations of both Washington and Moscow, and the careful attention paid to it in other key world capitals. The answer lies in the fact that, notwithstanding its self-characterization as a threatened and aggrieved state, China has very shrewdly and even brazenly used its available political, economic, and military resources. Towards the superpowers, Peking’s overall strategy has at various times comprised confrontation and armed conflict, partial accommodation, informal alignment, and a detachment bordering on disengagement, sometimes interposed with strident, angry rhetoric. As a result, China becomes all things to all nations, with many left uncertain and even anxious about its long-term intentions and directions.

只用武器、经济实力以及潜在力量等方面的数据,不可能说明中国对世界力量对比所产生的影响。如果只对它的战略地位做出不过分的估计,对它的经济活动作了充分的综合考虑,也还不能说明为什么中国在华盛顿和莫斯科所制定的战略中占有如此重要的地位,且不能说明为什么世界其他国家对它那么密切注视。问题的答案在于,尽管中国把自己塑造成受威胁、受委屈的样子,但它却机敏地利用了它可以利用的政治、经济和军事手段。对于超级大国,中国的战略是在不同时期使用包含有对峙和武装冲突、部分和解、非正式的结盟或者建立脱离、接触等手段,而有时又夹杂着刺耳的、愤怒的言辞。结果,中国变成了对所有国家来说是一个什么都是的国家,而许多国家对中国的确切情况没有把握,因而热切希望了解它的长远意图和方向。

To be sure, such an indeterminate strategy has at times entailed substantial political and military risks. Yet the same strategy has lent considerable credibility to China’s position as an emergent major power. China has often acted in defiance of the preferences or demands of both superpowers; at other times it has behaved far differently from what others expect. Despite its seeming vulnerability, China has not proven pliant and yielding toward either Moscow or Washington. … For all these reasons, China has assumed a singular international position, both as a participant in many of the central political and military conflicts in the post war era and as a State that resists easy political or ideological categorization. … Indeed, in a certain sense China must be judged as a candidate superpower in its own right—not in imitation or emulation of either the Soviet Union or the United States, but as a reflection of Peking’s unique position in global politics. In a long-term sense, China represents a political and strategic force too significant to be regarded as an adjunct to either Moscow or Washington or simply as an intermediate power. 49

可以肯定地说,这种不明确的战略有时招致很大的政治和军事风险。然而,这样的战略也给中国作为一个成长中的主要大国的地位增添了可信性。中国经常蔑视两个超级大国的要求和爱好,而在另外一些时候,它的行为又出乎他人的意料。尽管它的弱点显而易见,但它从未对莫斯科或华盛顿表现出妥协或屈从……由于所有这一切,中国在国际上享有独特的地位。它不但是战后许多重要的政治和军事冲突的参加者,而且是一个不为随便形成的政治或意识形态组织所动的国家……其实,凭中国的分量,它在一定意义上应被看作是候补超级大国——并非仿效苏联或美国的那种超级大国,而是反映中国在全球政治中的独特地位的那种超级大国。从长远来看,中国代表着一种政治和战略势力,它是如此重要,以至于既不能把它看作是莫斯科或者华盛顿的附属物,也不能把它简单地看作是一种中间力量。

As a final point, it needs to be stressed again that although China is keeping a tight hold upon military expenditures at the moment, it has no intention of remaining a strategical “lightweight” in the future. On the contrary, the more that China pushes forward with its economic expansion in a Colbertian, étatiste fashion, the more that development will have power-political implications. This is the more likely when one recalls the attention China is giving to expanding its scientific/technological base, and the impressive achievements already made in rocketry and nuclear weapons when that base was so much smaller. Such a concern for enhancing the country’s economic substructure at the expense of an immediate investment in weapons will hardly satisfy China’s generals (who, like military groups everywhere, prefer short-term to long-term means of security). Yet as The Economist has nicely remarked:

最后一点,需要再强调一下,虽然中国目前对军费实施严格的限制,但它并不是要使自己在将来成为一个战略上无足轻重的国家。相反,中国越是按照柯尔贝尔的国家干预主义的方式促使经济迅速发展,它的发展就越有强权政治的含义。当你回顾一下中国是怎样重视加强它的科技基础建设,以及它在其科技基础还是如此薄弱之时就在火箭和核武器技术方面取得了那样惊人的成就时,你就会更加清楚地看出这种含义。这种以牺牲对武器研制的直接投资为代价去加强国家的经济基础结构,将很难使中国的将军们满意(他们像任何地方的军人一样,都更喜欢得到近期的而不是长远的安全手段)。《经济学人》杂志对此有很好的评论:

For [China’s] military men with the patience to see the [economic] reforms through, there is a payoff. If Mr. Deng’s plans for the economy as a whole are allowed to run their course, and the value of China’s output quadruples, as planned, between 1980 and 2000 (admittedly big ifs), then 10 to 15 years down the line the civilian economy should have picked up enough steam to haul the military sector along more rapidly. That is when China’s army, its neighbors and the big powers will really have something to think about. 50

对于(中国的)军人来说,他们以极大的忍耐来度过经济改革的全过程,是会得到报偿的。这就是,如果邓小平先生的经济总体发展计划能够顺利完成,中国的国民生产总值能够按计划于1980到2000年间增长4倍(这是公认的宏大假设),那么在10到15年的时间内,民用经济将能够积蓄足够的力量,全力推动军事部门以更快的速度发展。到那时,中国的邻国和大国就真的要好好考虑中国的军队了。

It is only a matter of time.

这只不过是个时间问题。