The EEC—Potential and Problems

得失并存的西欧

Of the five main concentrations of economic and military power in the world today, the only one that is not a sovereign nation-state is Europe—which at once defines the chief problem facing this region as it moves toward the emerging Great Power system of the early twenty-first century. Even if our consideration of the continent’s future prospects excludes the Communist-controlled regimes in the east (as, for practical reasons, it must), we are still left with some states which are members of an economic-political organization (the EEC) but not of the chief military alliance (NATO), with others which adhere to the latter but not the former, and with important neutrals which are members of neither. Because of such anomalies, this section will focus upon the European Economic Community (and upon the policies of some of its leading members) rather than upon non-Communist Europe as a whole—for it is only in the EEC that an organization and structure exists, at least potentially, for a fifth world power.

就当前世界五大经济和军事力量中心来说,唯一不具备主权国家性质的实体是欧洲——这清楚地表明这一地区在走向21世纪初期的新兴大国体系的过程中所面临的主要问题。即使我们在考虑本大陆的未来前景时把东方社会主义政权排除在外(从实际可行的理由上看,必须排除在外),我们仍然不准备谈论某些国家——这些国家有的属于某个经济政治组织(欧共体),但不属于主要军事联盟(北约)的成员国;有的属于北约,但不是欧共体成员国;有的是与两类组织都无关的重要的中立国。由于这些不同情况的存在,接下来我们将集中讨论欧共体(以及某些主要成员国的政策),而不是重点讨论整个非共产主义的欧洲,因为形成世界第五力量的组织和结构是欧共体(至少潜在地存在着)。

But it is precisely because we are examining the EEC’s potential rather than its present reality that the problem of guessing what it may be like in the year 2000 or 2020 is compounded. In some ways the situation is similar to that which, on a smaller scale, faced the members of the German Federation in the mid-nineteenth century. 85 A customs union existed which had proved to be so successful in stimulating trade and industry that it rapidly attracted new members, and it was clear that if that enlarged economic community was able to turn itself into a Power state it would be a major new actor in the international system—to which the established Great Powers would have to adjust accordingly. But so long as that transformation did not occur; so long as there were divisions among the members of the customs union about further economic integration and, still more, about political and military integration; so long as there were quarrels about which state should take the lead and disputes between the various parties and pressure groups about the benefits (or losses) accruing to them, then just so long would it stay divided, unable to realize its potential, and incapable of dealing as an equal with the other Great Powers. For all the differences of time and circumstance, the “German question” of the last century was a microcosm of the “European problem” of the present.

但是,正是因为我们要讨论的是欧共体的潜在发展而不是它的现实,才使得我们对它在2000~2020年可能是个什么样子的推测变得复杂起来。从某些方面看,欧共体的形势,类似德意志邦联成员在19世纪中期在较小规模上所面临的形势。当时,它建立了一个关税同盟。关税同盟证明在刺激贸易和工业上获得了巨大的成功,以致它迅速吸引了一些新成员参加该同盟,并且事情非常清楚,如果这个扩大的经济共同体能够使自己变成一个大国,它就能在国际舞台上扮演一个重要的新角色——已有的大国将被迫做出相应的调整。但是,只要那种变革没有发生,只要关税同盟各成员在进一步经济一体化问题上存在着分歧,在政治和军事一体化上存在着分歧,只要在应由哪个国家担任领袖问题上有争吵,各派和实力集团在得或失的问题上有争端,它就会永远处于分裂状态,无法实现它的潜在发展可能,无力与其他大国分庭抗礼。尽管时代和环境有种种不同,但上一世纪的“德意志问题”仍是当今“欧洲问题”的缩影。

In its potential the EEC clearly has the size, the wealth, and the productive capacity of a Great Power. With the adherence of Spain and Portugal, its twelvemember population now totals around 320 million—which is 50 million more than the USSR and almost half as big again as the U. S. population. Moreover, it is a highly trained population, with hundreds of universities and colleges across Europe and millions of scientists and engineers. While its average per capita income conceals great gulfs—say, between West German and Portuguese incomes—it is much richer on the whole than Russia, and some of its member states are richer per capita than the United States. As was pointed out earlier, it is by far the largest trading block in the world, although much of that is intra-European trade. Perhaps a better measure of its economic strength lies in its productive output, in automobiles, steel, cement, etc. , which puts it ahead of the United States, Japan, and (except in steel) the USSR. Depending upon the annual statistics, and upon the wild swings in the value of the dollar relative to European currencies over the past six years, the total GNP of the EEC is about equal (1980, 1986) to that of the USA, or about twothirds as big (1983–1984 figures). It is certainly far larger than Russia, Japan, or China in its share of world GNP or manufacturing output.

从潜力上看,欧共体显然拥有一个大国所具有的规模、财富和生产能力。西班牙和葡萄牙加入后,其12个成员国的总人口已达3.2亿,要比苏联的人口多5000万人,几乎比美国多一倍。不仅如此,成员国的人口具有高度的文化素养,欧洲还有数百所大学和学院,有数百万名科学家和工程师。尽管各国的人均收入差距很大(联邦德国与葡萄牙两国的人均收入就相差甚远),但从整体上看,欧共体要比苏联富庶得多;若按人均计算,其某些成员国比美国还富。我们在前面已经指出,尽管其贸易的很大一部分是欧洲地区性贸易,但欧共体仍是世界上最大的贸易集团。也许测定其经济实力的更佳尺度是其产量,如汽车、钢、水泥等,欧洲这些产品的产量(钢除外)都超过了美国、日本和苏联。根据每年的统计数字和近6年来美元对欧洲货币比值巨大的变化,欧共体的国民生产总值大约相当于美国(1980年、1986年),或大约相当于美国的2/3(1983~1984年的数字)。就在世界国民生产总值中或工业品中所占的比重来说,欧共体无疑远远大于苏联、日本和中国。

In military terms also, the European member states are far from negligible. Taking only the four largest countries (West Germany, France, Britain, Italy) into account, one finds their combined regular-army size to be over a million men, with a further 1. 7 million in reserves86—a total which is of course smaller than the Russian and Chinese armies, but considerably larger than the U. S. Army. In addition, these four states possess hundreds of major surface warships and submarines and thousands of tanks, artillery, and aircraft. Finally, both France and Britain possess nuclear weapons, and delivery systems—sea-based and land-based. The implications and effectiveness of these military forces will be discussed below; the point being made here is simply that, once combined, the totals are very substantial. What is more, the spending upon these forces represents around 4 percent of the GNP, as a rough average. Were those countries, or, more significant still, the entire EEC, spending around 7 percent of total GNP on defense, as the United States is today, the sums allocated would be equal to hundreds of billions of dollars—that is, roughly the same amount as the two military superpowers spend.

此外,从军事方面看,这些欧洲国家也是不容忽视的。人们发现,欧洲4个最大的国家(联邦德国、法国、英国和意大利)的陆军总兵力超过100万人,还有170万预备役人员。两者合起来虽仍小于苏联陆军和中国陆军,但大于美国陆军。此外,这4个国家还拥有几百艘大型水面舰只和潜艇,数千坦克、火炮和飞机。最后,法国和英国还都拥有核武器和陆基、海基发射系统。对于这些军事力量的意义和效力,本书下面还将述及,但这里可简单地指出一点:如果联合起来,其总数和总效力非常可观。尤其重要的是,这些军事力量的开支平均约占国民生产总值的4%。如果这些国家——或更有意义的是如果整个欧共体的防务开支像今天美国那样达到国民生产总值的7%左右,那么,分配给防务的经费总数就会有数千亿美元,大体与两个超级大国的军费开支相同。

And yet Europe’s real power and effectiveness in the world is much less than the crude total of its economic and military strength would suggest—simply because of disunity. The armed forces, for example, not only suffer from a multitude of languages (a problem which the German Federation’s members never had to face), but are equipped with many different weapons and have very marked differences in quality and training—between, say, the West German and the Greek armies, or the Royal Navy and the Spanish navy. Despite NATO’s many attempts at standardization, one is still talking about a dozen armies, navies, and air forces of varying worth. But even those problems pale beside the obstacles at the political level, relating to the foreign and defense policy priorities of Europe. Ireland’s traditional (and anachronistic) stance on neutrality prevents the EEC from discussing defense issues—although even if discussions occurred, they would probably soon founder upon Greek objections. Turkey, with its substantial army, is not a member of the EEC; and the Turkish and Greek armed forces often seem more worried about each other than about the Warsaw Pact. France’s independent stance has (as will be seen below) military advantages and disadvantages; but it adds to the complications of consultation on defense and foreign-policy matters. Both Britain and France indulge in “out of area” operations and, indeed, still maintain an array of bases and troops overseas. For West Germany, the overriding defense issue— toward which all its forces are geared—is the security of its eastern frontier. Evolving a unified European policy toward, say, the Palestinian issue, or even toward the United States itself, is inordinately complex (and often fails), because of the differing interests and traditions of each of the member states.

但是,欧洲在世界上的实际力量和效力大大低于其经济实力和军事实力本应达到的水平,其原因就在于欧洲不统一。以武装部队为例,欧洲军队不仅受损于语言不同(过去德意志邦联从未遇到过这个问题),而且还受损于五花八门的武器装备和相差悬殊的军事素质、训练水平。例如联邦德国陆军与希腊陆军、英国皇家海军与西班牙海军就无法相提并论。尽管北约组织做了许多标准化的尝试,但人们仍在埋怨12支陆、海、空军参差不齐。然而,在涉及到欧洲的对外政策和防务政策孰重孰轻时,这些问题与政治方面的障碍相比,就显得黯然失色了。爱尔兰传统的(和无政府主义的)中立立场,妨碍了欧洲经济共同体讨论防务问题;纵然进行这方面的讨论,这些讨论也许会在希腊的反对下很快收场。土耳其拥有一支庞大的陆军,但它不是欧共体的成员国。土耳其和希腊的武装部队对对方的忧虑常常甚于对华约军队的担心。法国的独立立场(下面将看到)在军事上既有有利的一面,也有不利的一面,而它的这种立场使防务和外交政策问题的协商更加复杂。英国和法国都对“在本地区之外”搞军事行动持放任态度,并且确实仍然在海外保持一系列的军事基地和驻军。对联邦德国来说,凌驾于一切的防务问题——它的全部军队所注意的问题——是东部边界的安全问题。对于欧洲来说,制定一项统一的欧洲对(例如)巴勒斯坦问题的政策,或者对美国本身的政策,由于各成员国的利益和传统不同而显得格外复杂(并且常常失败)。

In terms of economic integration, and of the constitutional and institutional arrangements that exist to implement decisions in the economic field, the EEC is obviously much further ahead; even so, as an “economic community,” it is much more splintered than a sovereign state would ever be. Political ideology always affects economic policy and priorities. Coordination is difficult, if not impossible, when socialist regimes are in power in some of the member states and conservative parties are dominant in the others. Although the coordination of currencies is now more successful than it was, the occasional realignments which do take place (usually involving a revaluation of the German mark) are a reminder of the separate fiscal systems—and differentiated credit-worthiness—of the members. Despite proposals from the European Commission, there is as yet little progress toward a common European policy on a whole variety of issues, from full-scale airline deregulation to financial services. At too many of the common frontiers there are still customs posts, and lengthy checks, to the fury of the truck drivers. Even agriculture, the mainstay of the EEC’s spending functions and one of the few economic sectors where there is a “common market,” has proved to be a bone of contention. And if it is indeed likely that world foodstuffs production will continue to expand, with India and other Asian countries increasingly entering the export markets, the pressure to reform the EEC’s price-support system will build up, until the issue explodes into heated controversy again.

从经济一体化和为了实现经济领域的决策而制定的宪章和法规制度上看,欧共体显然大大走在了前头,但即使如此,作为一个“经济共同体”来说,其分裂状态也远远超过了一个主权国家所可能发生的。政治意识形态总是影响经济政策和经济决策轻重缓急的顺序。当社会党政权在某些成员国执政而保守党在另一些成员国当权时,协调工作即使不是不可能,也是困难重重。虽然现在货币的协调比以往更加成功,但是有时不得不重新做出安排(通常包括重新调整德国马克的币值)这一事实,却提醒我们注意到成员国之间所存在的不同的财政制度和各异的银行存款制度。尽管欧洲委员会提出了有关建议,但对于制定一项欧洲共同的政策来处理各种各样的问题,从全部解除对航班的限制到金融服务,却没有取得什么进展。在很多的共同边界上,仍然关卡林立,烦琐的检查手续激起卡车司机们的愤慨。农业是欧共体的主要支柱,是有着“共同市场”的几个经济部门之一,但农业也是一个争论不休的问题。而且,如果世界粮食生产真能继续扩大,印度和其他亚洲国家不断进入出口市场,那么要求改革欧共体的价格补贴制度的压力将会增大,直到问题再次爆发为激烈的争论为止。

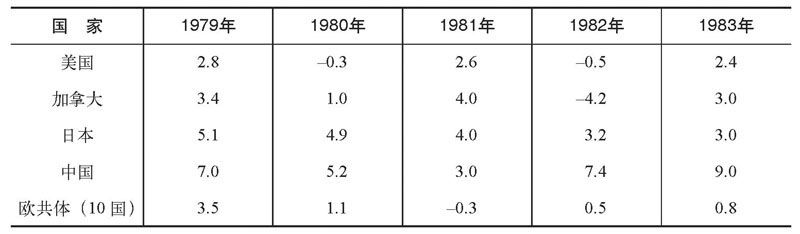

Finally, there is the persistent worry that after its postwar decades of economic growth and success, Europe is beginning to stagnate, and perhaps even to decline. The problems caused by the oil crisis of 1979—the steep rise in fuel prices, the pressure upon balance of payments, the general world depression in demand, output, and trade—seemed to hit the Europeans harder than many of the other major economies of the earth, as is indicated by Table 45.

最后,人们还一直担心下面这种情况:经过战后几十年经济的发展和获得成功之后,欧洲开始进入不景气,甚至可能进入衰落状态。1979年石油危机引起的问题——燃料价格猛涨,收支平衡所受的压力,全世界在需求、产量和贸易方面的普遍萧条——给欧洲人的打击似乎比对其他许多主要经济大国的打击更重,参见表45。

Table 45. Growth in Real GNP, 1979–1983 87 (percent)

表45 1979~1983年国民生产总值实际增长情况表(%)

One of the chief concerns of the European states has been the effect of this slump upon employment levels—the number of people losing their jobs in western Europe in recent years has been much higher than at any time in the post-1945 era (for example, it leaped from 5. 9 million to 10. 2 million within the EEC between 1978 and 1982) and has shown little sign of coming down—which in turn swells the already extremely high level of social expenditures, leaving less for investment. 88 Nor has there been anything like the creation of new jobs on the scale which has occurred in the United States (chiefly in low-paying service industries) and Japan (in high technology and services) as the 1980s have unfolded. Whether one ascribes this to the lack of business incentives, high costs and immobility of the labor market, and bureaucratic over-regulation (as right-wingers tend to do), or to the failure of the state to plan and invest sufficiently (as the Left usually sees it), or to a fatal combination of both, the result is the same. More alarming still, to many commentators, have been the signs that Europe is falling behind its American and (especially) its Japanese competitors in the high-technology stakes of the future. Thus, the 1984–85 Annual Economic Report of the European Commission warned:

欧洲国家所关心的主要问题之一,一直是这一衰退对就业水平的影响——近些年来,西欧失业人数一直大大高于1945年以来的任何时期(1978~1982年,欧共体内的失业人数由590万人猛增到1020万人),并且没有下降的迹象。这种现象反过来又使本来已经增至极高水平的社会开支膨胀起来,从而减少了投资。而且,也没有出现像20世纪80年代发生的那种情况——美国已经大规模创造新职业,主要表现在低工资的服务性行业方面。日本也发展了新职业,主要表现在高技术领域和服务性行业方面。不管人们把这一切归咎于缺乏职业刺激、高开支和劳动力市场的不活跃以及官僚们的过分节制(右翼人士倾向于这样做),或国家在制订有效的计划与投资方面的失误(左翼人士通常这样认为),还是归咎于这两方面的致命结合,其结果都是一样的。更使许多评论家惊奇的是下面这种迹象:在未来的高科技赌注上,欧洲正落在美国以及(尤其是)日本竞争对手的后面。因而,欧洲委员会的《1984~1985年度经济报告》发出了如下警告:

The Community is now having to respond to the challenge of an emerging inferiority, by comparison with the United States and Japan, in industrial capacity in new and fast-growing technologies. … The deteriorating world trade performance of the Community in such fields as computers, micro-electronics, and equipment is now generally recognized. 89

现在,欧共体与美国和日本相较,在新的和快速发展的技术方面的工业生产能力,面对着正在出现的劣势的挑战,必须做出反应……现在,人们普遍承认欧共体在电子计算机、微电子技术和设备等领域的世界贸易活动中面临着日益恶化的局面。

Quite possibly, this picture of “Eurosclerosis” and “Europessimism” has been painted too gloomily, for there are many other signs of European competitiveness—in quality automobiles, commercial and fighter aircraft, satellites, chemicals, telecommunications systems, financial services, etc. Nevertheless, the two most pressing issues remain in doubt. Is the EEC, because of the sociopolitical diversity of its members, as capable as its overseas competitors of responding to swift and largescale shifts in employment patterns? Or is it designed more to slow down the impact of economic changes upon uncompetitive sectors (agriculture, textiles, shipbuilding, coal, and steel), and, in being so humane in the short term, disadvantaging itself in the longer term? And is the EEC capable of mobilizing the scientific and investment resources to remain a leading contender in the high-technology stakes, when its own companies are nowhere near as big as the American and Japanese giants, and when any “industrial strategy” has to be worked out, not by the likes of MITI, but by twelve governments (plus the EEC Commission), each exhibiting different concerns?

十分可能的是,这种“欧洲硬化症”和“欧洲悲观主义”画面的色彩被涂得过于暗淡,因为还有其他许多迹象表明,欧洲是有竞争力的,如高质量的小轿车、民用和战斗机、卫星、化工产品、电信系统、财政金融服务等。尽管如此,有两个最紧迫的问题仍然是未知数。欧共体(由于其成员国的社会政治体制十分复杂)能够像它的海外竞争对手那样对就业方式迅速而巨大的变化做出反应吗?或者说,它打算做出更大努力来减少经济变革对非竞争性生产部门(农业、纺织业、造船业、煤炭和钢铁工业)的影响,并在短期内做得十分人道,而长期看来却使本身处于不利地位吗?另一个问题是,欧共体的公司规模不如美国和日本的大公司,它的任何“工业战略”都不是由日本通商产业省一类的机构来制定的,而是由各有不同打算的12个成员国政府(以及欧洲委员会)来制定的,在这种情况下,它能够动员自己的科学和财政力量来保持其在高科技领域竞争中的有利地位吗?

If one turned one’s attention from the EEC as a whole to a brief examination of the situation in which the leading three military/political countries of Europe find themselves, the sense of “potential” being threatened by “problems” is only reinforced. No state, arguably, manifests this ambivalence about the future more than the Federal Republic of Germany, in large part because of its inheritance from the past and the still “provisional” nature of the present structure of Europe.

如果我们把注意力从整个欧共体移开,短暂审视一下欧洲的三个居主导地位的军事—政治强国面临的形势,那我们就会进一步看到欧共体的“潜力”正在受到“问题”的严重威胁。没有任何国家像联邦德国那样对未来怀有一种矛盾心理。它之所以这样,在很大程度上是由于它与过去的欧洲仍然藕断丝连以及当前的欧洲结构仍然带有“临时”性质。

Although many Germans fret about the economic prospects for their country by the early twenty-first century, that can hardly be regarded as the major concern (especially as compared with the economic difficulties facing other societies). While its total labor force is only a little higher than Britain’s or France’s, its GNP is significantly larger, reflecting an economy whose long-term productive growth has been extremely impressive. It is the largest producer in the EEC of steel, chemicals, electrical goods, automobiles, tractors, and (given Britain’s decline) even merchant ships and coal. Because of a remarkably low level both of inflation and of labor disputes, it has kept its export prices competitive, despite the frequent upward valuations of the deutsche mark—which are, after all, merely belated acknowledgments by other nations of West Germany’s better economic performance. A heavy emphasis upon engineering and design in the German management tradition (as opposed to the American emphasis upon finance) has given it an international reputation for quality products. Year after year, the German economy has notched up a surplus in its trade balances second only to Japan’s. Its international reserves are larger than those of any other country in the world (except, presumably, those of Japan after the latter’s recent surge), and the deutsche mark is often used by other nations as a reserve currency.

尽管许多德国人对于他们的国家到21世纪初期的经济前景表示不安,但这种不安情绪并不十分严重(尤其是同其他国家所面临的经济困难比较起来看)。虽然它的劳动力总额稍多于英国和法国,但其国民生产总值却高得多,这反映出它的劳动生产率长期以来一直很高。在欧共体中,联邦德国一直是钢、化工产品、电子产品、汽车、拖拉机以及(由于英国经济活动衰落)船舶和煤炭的最大生产国。由于它的通货膨胀率极低,劳资纠纷很少,尽管德国马克不断升值,它却保持着出口商品价格的竞争性(它终于使其他国家认识到它的经济效益很高)。联邦德国有十分重视工程与设计的管理传统(美国却重视财政金融),这使联邦德国的高质量产品在国际享有盛誉。多年来,联邦德国在收支方面一直有盈余,盈余额仅次于日本。它的国际外汇储备多于世界上任何国家的外汇储备(日本由于最近几年获得了极大的增长,可能除外),其他国家常常把德国马克留作储备货币。

As against all this, one can point to those factors which give the Germans cause for Angst90 The EEC’s agricultural price-support system, long a drain for the German taxpayer, redistributes resources from the most competitive to the least competitive sectors of the economy—and not just in the Federal Republic itself (where there are a surprisingly large number of small farms), but to the peasantry of southern Europe. This has obvious social value, but it is a burden proportionately much larger than the protection given to American and perhaps even to Japanese agriculture. The persistently high level of unemployment, a sign that the Federal Republic still has too large a proportion of its work force in older industries, is also a major drain upon the economy, keeping social-security payments at a very high proportion of GDP; and while unemployment among the youth can be alleviated by the impressively broad level of training and apprenticeships, and will also be eased by the rapid aging of the German population, this latter trend is perhaps regarded with the greatest unease of all. If it is clearly an exaggeration to believe that the German race will “die out,” the steep decline in the birth rate will have obvious repercussions upon the German economy when an even larger share of the population consists of old-age pensioners. Along with this demographic fear goes the much less tangible worry that the “successor generation” will not want to work as earnestly as those who rebuilt Germany from the wartime ashes, and that with higher wage costs and far shorter working weeks than the Japanese, even German productivity growth will not keep up with the challenge from the Pacific basin.

了解到上述情况后,人们便不难看到当今德国人不安的因素了。欧共体的农产品价格补贴制度加重了德国纳税人的负担,使资源从最具有竞争性的产业部门转移到竞争性最差的部门。这种情况不仅在联邦德国(令人不解的是,联邦德国有大量的小农场)有,在南欧的农业区也有。这虽然有明显的社会价值,但同美国以及日本为其农业提供的保护相比,负担却大得多。长期的大量失业(这说明联邦德国在它的老式产业中有一支过分庞大的劳动力大军),也是一个于国家经济不利的重要因素,因为这会使社会保险金在国内生产总值中占有很大比重。虽然通过实施大规模培训和招收徒工计划(加上联邦德国人口的迅速老龄化)可使青年当中的失业问题得到缓解,但人口老龄化趋势可能引起德国人的严重不安。认为日耳曼民族将“消失”显然是一种夸张的说法,但人口出生率急剧下降,将对联邦德国经济产生不良影响,特别是在联邦德国人口中将有更多的人是养老金领取者时,情况更是如此。除了这种人口方面的担心外,还有一种很不易感觉的担心,即“下一代”将不像使联邦德国从战争废墟上站立起来的一代人那样认真对待自己的工作。随着高工资和较之日本短得多的工作时间等制度的实行,联邦德国的生产增长率将逐渐变得低于太平洋地区各国。

Even so, none of those problems are insuperable, provided the Germans can maintain their “package” of low inflation, quality goods, high investment in new technology, superior design and salesmanship, and labor peace. (At the very least, one can say that if the problems named above affect the German economy, how much more will they hurt the economies of most of its less competitive neighbors!) What is much more difficult to forecast is whether the extraordinarily complex and quite unique contours of the “German question” as they have existed since the late 1940s will continue unchanged into the twenty-first century: that is, whether there will continue to be two “Germanies,” separated by hostile alliances, despite the growing intimacy between them; whether the NATO alliance (of which the Federal Republic is such a central part) can defend the German lands without destroying them, should East-West relations worsen into hostilities; and whether, in the event of a diminution in American power and a reduction of its forces in Europe, Germany and its major EEC/NATO partners can provide an adequate substitute for the U. S. strategic umbrella which has served so well for the past forty years. None of these interrelated issues are crying out for an immediate solution, but all of them are giving thoughtful observers grounds for concern.

即使如此,如果联邦德国人能够保持低通货膨胀率、产品优质、对开发新技术进行大量投资、在产品设计上高出一筹、有良好的经商作风以及劳资和平相处,这些问题都是可以解决的。(至少人们可以说,如果上面所提到的那些问题给联邦德国经济带来了影响,那么这些问题将对经济竞争能力低的邻国造成更大的伤害。)更加难以预测的是,自20世纪40年代末期以来一直存在的非常复杂的“德国问题”,是否将继续存在到21世纪。这也就是说:由两个敌对的联盟分开的两个“德国”是否将长期存在,尽管它们之间的关系日益亲密?如果东西方关系恶化,且爆发战争,北约(联邦德国在其中占有重要地位)能否在不使联邦德国遭到破坏的情况下保卫它的土地?一旦美国的力量减弱、削减驻欧兵力,联邦德国及其他欧共体和北约成员国能否提供充分的力量,代替过去40年来一直发挥良好作用的美国战略保护伞?这些互相关联的问题都不可能立即得到解决,但又都是有思想的观察家必须关心的。

The “German-German” relationship will probably seem, at this time, the most hypothetical of the cluster. As has been made clear in the preceding chapters, the proper place of the German people within the European states system has troubled statesmen for at least the past century and a half. 91 If all those speaking the German tongue are brought together as one nation-state—as has been the European norm for nearly two centuries—the resultant concentration of population and industrial might would always make Germany the economic power center of west-central Europe. That itself need not necessarily turn it into the dominant military-territorial force in Europe as well, in the way that the imperialism of both the Wilhelmine and (even more) the Nazi eras led to a German bid for hegemony. In a bipolar world which, militarily, is still dominated by Washington and Moscow, in an age when major Great Power aggressions run the risk of triggering a nuclear war, and with a post-1945 “de-Nazified” generation of German politicians running affairs in Bonn and East Berlin, the notion of any future Germanic bid for “mastery in Europe” seems anachronistic. Even were it attempted, the balance of European (let alone global) power would prevail against it. In abstract terms, therefore, there is surely nothing wrong and a lot that is right with permitting the 62 million “West” Germans and 17 million “East” Germans to reunite, particularly when each population increasingly perceives that it has more in common with the other than with its superpower guardian.

目前,两个德国的关系是所有这些问题中最棘手的一个问题。如前几章所阐明的那样,确定德意志民族在欧洲国家体系中的适当位置至少在过去一个半世纪中一直是政治家们感到头痛的问题。如果把所有说德语的人放在一起,组成一个民族国家(就像近两个世纪中许多欧洲人要求做的那样),这种最终人口和工业力量都集中起来的德国很可能成为中西欧的经济力量中心。这种情况未必一定会导致德国成为欧洲的一流军事强国,就像德皇威廉二世和(更为甚者)纳粹时代企图称霸世界的德国那样。在一个两极世界中(从军事上看,这个两极世界依然由华盛顿和莫斯科控制,并处于大国侵略行动有可能导致核战争的时代,且波恩和东柏林已由1945年后“非纳粹化”的一代德国政治家处理国事),德国未来任何企图“称霸欧洲”的观念,都是不合乎时代要求的。即使它打算这样做,其他欧洲国家(更不要说世界各国)也会制止它。因此,从理论上说,让6200万联邦德国人和1700万民主德国人重新统一起来,尤其是当双方因越来越清楚地看到它们之间的相同点多于与保护它们的超级大国的相同点,而统一起来,这肯定不是一种错误,而是完全正确的。

Yet the tragic fact is that however logical that solution is in one sense—and however much the two German peoples are showing signs (despite the ideological gulf) of their common inheritance and culture—the present political realities speak against it, even if it took the form of a loose Germanic federation on the nineteenthcentury model, as has been ingeniously suggested. 92 For the blunt fact is that East Germany serves as a strategical barrier for the Soviet control over the buffer states of eastern Europe (not to say the jump-off position for a move to the west); and since the men in the Kremlin still think in terms of imperialist Realpolitik, letting the German Democratic Republic gravitate toward (and into) the Federal Republic would be regarded as a major blow. As one authority has recently pointed out, based on present forces alone, a unified Germany could field over 660,000 regular troops plus 1. 5 million paramilitary and reservists. The USSR could not view with equanimity a unified German nation with an army of 2 million on its western flank. 93 On the other hand, it seems difficult to see why a peacefully united Germany should want to maintain armed forces of that size, forces which reflect present Cold War tensions. It is also difficult to believe that despite its heavy-handed emphasis upon the lessons of the Second World War, even the Soviet leadership accepts its own propaganda about German revanchism and neo-Nazism (which has been an increasingly difficult position to maintain since Willy Brandt’s period of office). But what is also clear is that Moscow has a congenital dislike of withdrawing from anywhere, and also worries deeply about the political consequences of a reunited Germany. Not only would it be a formidable economic Power in its own right—with a total GNP dangerously close to the USSR’s own, at least in formal dollarequivalent terms—but it also would act as a trading magnet for all of its eastern European neighbors. Even more fundamental a point: how could Russia withdraw from East Germany without provoking the question of a similar withdrawal from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland—leaving as the USSR’s western frontier the dubious Polish/Ukrainian borderline, which is temptingly close for the fifty million Ukrainians?

然而,可悲的是,不管上述解决办法从某种意义上说多么合乎情理,也不管两个德国的人民多么充分表示他们有共同的传统和文化(尽管他们在意识形态方面还存在分歧),政治现实却对他们说不,即使仿照19世纪的模式建立松散的德意志邦联(对此,人们曾巧妙地提出建议)也不行。这里有一个无情的现实,即民主德国是苏联控制东欧缓冲国家的战略屏障(更不必说也是向西方进军的一个跳板了)。由于克里姆林宫的掌权者仍然从帝国主义现实政治的角度思考问题,因此他们认为,民主德国向联邦德国靠拢(并与之合并)是对他们的一个重大打击。一位权威人士根据目前两个德国的兵力情况指出,一个统一的德国可以部署66万多人的正规军、150万人的准军事和预备役部队。苏联不能对在其西翼拥有一支200万人军队的一个统一的德国泰然处之。另一方面,人们不认为一个和平统一的德国应保持如此规模的军队(即一支反映“冷战”紧张局势的军队)。同样,尽管第二次世界大战给德国人的经验教训如此深重,苏联领导人却还是接受了自己所作的宣传——联邦德国执行复仇主义和新纳粹主义政策(自维利·勃兰特执政时期以来,这种政策实际上已无法在联邦德国执行)。但是,人们明显看到的另一点是,苏联根本不愿从任何地方撤走,并对德国重新统一的政治后果深感担忧。一个重新统一的德国不仅将是一个强大的经济大国(其国民生产总值将非常接近苏联,至少从官方美元换算值来看是如此),而且在贸易上将对苏联的所有东欧邻国起吸引作用。还有更为重要的一点是,苏联从民主德国撤军肯定会导致捷克斯洛伐克、匈牙利和波兰也要求苏联撤军。从这些国家撤军将使苏联的西部边界变为一条难以划定的波兰-乌克兰国境线,这条国境线的附近有5000万立场微妙的乌克兰人。

What remains, therefore, is a state of suspended animation. Intra-German trade relations are likely to grow (clouded only by the occasional tension between the superpowers); each German state is likely to become relatively more productive and richer than its neighbors; each will swear loyalty to its supranational military (NATO/Warsaw Pact) and economic (EEC/Comecon) organizations while making special arrangements with its Germanic sister state. It is impossible to forecast how Bonn would react should the Soviet Union itself be shaken and upset from within— and should that coincide with serious unrest in the German Democratic Republic. It is also impossible to forecast how the “East” Germans would react if there was to be a Warsaw-Pact offensive westward. Certainly, the special Soviet “control” arrangements over the Democratic Republic’s army, and the shadowing of every one of its divisions by a Russian motor-rifle division, suggest that even the grim men in the Kremlin worry about setting German against German—as well they should.

所以,目前看来两德的统一可望而不可即。两个德国之间的贸易可能增加(仅偶尔受超级大国之间紧张关系的影响),两个德国可能比邻国都具有较强的生产力和较富裕的财政;它们都将宣誓忠于各自的超国家军事组织(北约和华约)和经济组织(欧共体和经互会),同时又跟自己的姐妹国签署一些特别协定。人们无法预测,假如苏联因内部发生动乱而政局不稳,同时民主德国也发生动乱,波恩会做出何种反应。人们也无法预测,如果华约向西方发动进攻,民主德国人会做出何种反应。毋庸置疑,苏联为“控制”民主德国军队所做出的特别安排,以及用苏联摩托化步兵师来监视民主德国每个师的做法表明,甚至克里姆林宫内那些冷酷无情的掌权者也对让德国人打德国的情况表示忧虑(实际上他们也应当忧虑)。

But the more concrete and immediate problem which the Federal Republic faces —and has faced since its existence—has been to discover a viable defense policy in the event of a war in Europe. From the beginning (see pp. 378–79), the apprehension that a vastly superior Red Army could strike westward without much hindrance led both the Germans and their fellow Europeans to rely upon the U. S. nuclear deterrent as their chief security. Ever since the USSR acquired the capacity to hit the American homeland with its own ICBMs, however, that strategy has been in doubt—would Washington really begin a nuclear interchange in response to a Russian conventional attack on the northern German plain?—even if it has never been officially abandoned. This is also true of the related question of whether the United States would unleash strategic nuclear attacks against the Soviet Union (again, inviting reprisals upon its own cities) if the Russians contented themselves with firing short- or intermediate-range missiles (SS-20s) solely at European targets. There has been, to be sure, no lack of proposals for creating a “credible deterrent” to meet such contingencies: installing Pershing II and various forms of cruise-missile systems to counter the Russian SS-20s; producing an enhanced-radiation (or “neutron”) bomb, intended to kill off invading Warsaw Pact troops without damage to buildings and infrastructure; and—in the French case—reliance upon a Pariscontrolled deterrent force as an alternative to an uncertain American defense system. All of these, however, have their own attendant problems;94 and, quite apart from the political reactions which they provoke, each of them points to the uniquely contradictory nature of nuclear weapon systems—that having recourse to them is more than likely to lead to the destruction of that which one wishes to defend.

而联邦德国面临的——实际上从它产生之日起就一直面临的——一个更加具体和更加直接的问题是,制定一项在欧洲发生战争时执行的切实可行的防务政策。以一开始,联邦德国人及其欧洲盟国就对在兵力上占巨大优势的苏联红军能够不受多大阻碍地向西方实施突击感到忧虑,因而便以美国的核威慑力量作为保卫本国安全的主要手段。然而,自从苏联拥有用自己的洲际弹道导弹打击美国本土的能力以来,上述战略的有效性便成问题了(尽管从未正式宣布放弃这项战略):华盛顿真会发动一场核交锋来回击苏联对联邦德国北部平原的常规进攻吗?与此相关的另一个问题是,如果苏联人只使用短程或中程导弹(SS-20)打击欧洲目标,美国是否会向苏联发动战略核袭击(同样会招致对美国城市的回击)?无疑,人们提出了许多建议,要求建立“可靠的威慑力量”来应付紧急情况。例如,部署“潘兴-Ⅱ”式导弹和各种各样的巡航导弹系统,以对付苏联的SS-20导弹;生产一种既可消灭入侵的华约部队,又不给己方的建筑物和基础设施造成破坏的强辐射弹(或“中子弹”)。法国则主张建立一支由巴黎控制的威慑部队,以作为不可靠的美国防御系统的备用手段。但是,所有这些建议本身都有问题。除了可能引起政治反响外,所提出的每种办法都带有核武器系统所特有的自相矛盾的性质——使用核武器很可能使人们希望保卫的东西遭到破坏。

It is scarcely surprising, therefore, that while successive West German administrations have paid lip service to the value of NATO’s nuclear-deterrence strategy, and have foresworn the acquisition of nuclear weapons for themselves, they have been to the fore in the creation of a strong conventional defense system. As it is, the Bundeswehr has not only the largest of the NATO armies in Europe (335,000 troops, with 645,000 trained reserves)95 but also one of extremely high quality and with good equipment; provided it did not lose command of the air, it would give an impressive account of itself. On the other hand, the steeply declining birthrate makes it increasingly difficult to maintain the Bundeswehr at full strength, while the government’s desire to keep defense spending down to 3. 5 to 4 percent of GNP means that it will be difficult for the armed services to procure as much new equipment as they need. 96 At the end of the day, such weakness can be overcome— just as the deficiencies in the less-well-equipped Allied armies stationed in West Germany could be overcome, given the political will. However, this still leaves the Germans facing the uncomfortable (for some, intolerable) dilemma that any outbreak of large-scale hostilities in central Europe would lead to incalculable bloodshed and material loss on their territory.

所以,人们对下面这种情况并不感到奇怪:尽管联邦德国各届政府在口头上大讲北约核威慑的战略价值,并发誓自己要置办核武器,但它们却一直站在创建一支强大的常规防御部队的前列。事实也是这样,联邦德国国防军不仅拥有北约组织欧洲成员国中最大的陆军(33.5万人,另有64.5万受过训练的预备役人员),而且训练有素,装备精良。如果这支陆军部队再拥有制空权,它本身会发挥重大作用。另一方面,人口出生率的急剧下降又使联邦德国国防军越来越难以保持满员;而政府打算使防务开支只占国民生产总值3.5%~4%,又意味着武装部队将难以采购许多新式装备来满足自己的需要。这些弱点最终是能够克服的,正像只要政治意志坚决,驻联邦德国的装备不太好的盟国军队的不足也能得到克服一样。但是,这仍然无法使联邦德国人摆脱下述令人不安的(对某些人来说,是不能容忍的)困境:在中欧爆发任何大规模战争,都会在他们的领土上造成无法估量的人员伤亡和物质损失。

It is not surprising, therefore, that since at least the time of Willy Brandt’s chancellorship the government in Bonn has been to the fore in its pursuit of détente in Europe—and not merely with its German sister state, but also with eastern European nations and with the USSR itself, in an endeavor to calm their traditional fears of a too-strong Germany; and that it, more than all its NATO partners, has partaken in and financed East-West trade in the Cobdenite belief that economic interdependence makes war more difficult (and also no doubt because West German banks and industries are so favorably placed to take advantage of that commerce). This does not imply a move into “neutralism” for the two Germanies—as is sometimes proposed by left-wing Social Democrats and the Green Party—for that would depend upon securing Moscow’s consent to East German neutralism as well, which is highly unlikely. What it does mean is that West Germany sees its security problem concentrated almost exclusively in Europe and shuns any “out-of-area” capability—let alone the occasional extra-European actions in which the French and British still indulge. By extension, therefore, it dislikes being forced to take a position on the (in its view) distracting and distant issues in the Near East and farther afield, and that in turn leads it into disagreements with a U. S. government which feels that the preservation of western security cannot be so neatly limited to central Europe. In its relationship to Moscow and East Berlin on the one hand and to non-European issues on the other, West Germany finds it difficult if not impossible to conduct a merely bilateral diplomacy; it must, instead, have regard for the reactions of Washington (and, often, of Paris). That, too, is a price which has to be paid for its awkward and unique position in the international power system. 97

因此,毫不奇怪,至少自维利·勃兰特担任政府总理时期开始,联邦德国一直在积极地寻求欧洲局势的缓和——不仅主张同民主德国缓和关系,还主张同东欧各国以及苏联缓和关系,以便消除它们那种传统的对太强大的德国的恐惧。同所有北约成员国相比,联邦德国更多地参与和资助了东西方贸易,因为它坚信科布登[6]的信条:经济上的相互依赖,可使战争更加难以发生(毫无疑问,还因为联邦德国的银行和工业处于非常有利的便于进行贸易的地位)。这并不意味着两个德国要实行“中立化”(就像左翼社会民主党人和绿党有时所建议的那样),因为那样做还要使苏联也同意民主德国中立化,而这是非常不可能的。但是,这的确意味着,联邦德国在安全问题上几乎完全把注意力放在了欧洲,不想获得任何“到国外”作战的能力,更不用说偶尔在欧洲以外地区采取作战行动了(法国和英国却仍然这样做)。所以,再进一步看,联邦德国还不愿意别人强迫它介入中东和更远地区那些与它无关并分散它的力量的争端。这种情况反过来又使它不同意美国政府的下述观点:美国政府认为,保卫西方安全不能只限于中欧地区。联邦德国政府感到,在处理同苏联和民主德国的关系以及在处理欧洲以外地区发生的问题时,仅仅搞双边外交即使不是不可能也是很困难的。它必须考虑华盛顿(而且常常还有巴黎)的反应。它在国际力量体系中处于困难而独特的境地,因而不得不付出一定的代价。

If the Federal Republic finds the economic challenges less intractible than foreignand defense-policy problems, the same cannot be said for the United Kingdom. It, too, is the legatee of a historical past—and, of course, of a geographical position— which strongly influences its policy toward the world outside. But, as we have seen in earlier chapters, it is also the country among the former Great Powers whose economy and society have found it hardest to adjust to the shifting patterns of technology and manufacturing in the post-1945 decades (and in many respects in the decades before). The most devastating impact of the global changes has been upon manufacturing, a sector which once earned Britain the title “workshop of the world. ” It is true that among many of the advanced economies of the world, manufacturing’s share of output and employment has been steadily shrinking while other sectors (e. g. , services) have grown; but in Britain’s case the fall has been much more precipitous. Not only has its proportion of world manufacturing output continued its remorseless decline relatively, but it has also decreased absolutely. More shocking still has been the abrupt switch in the place of manufactures in Britain’s foreign trade. While it may be difficult to prove The Economist’s tart observation that “since 1983, Britain’s trade balance on manufactures has been in deficit for the first time since the Romans invaded Britain,” it is a fact that even in the late 1950s exports of manufactures were three times as big as imports. 98 Now that surplus has gone. What is more, the decline in employment occurs not only in older industries but also in the “sunrise” high-technology firms. 99

似乎联邦德国感到应付经济挑战要比处理对外政策和防务政策问题容易些,而英国的情况却恰恰相反。英国也有很长的历史,它的地理位置也有历史渊源,这一切都强烈地影响着它的对外政策。但是,正如我们在前几章所看到的,在以前的大国中,英国也是一个发现自己的经济和社会很难适应1945年以后几十年(在许多方面,也包括1945年以前的几十年)中在技术和生产制造业方面不断发生变化的格局。全球性变革对它的生产制造业影响最大,而其生产制造业曾使英国赢得过“世界工厂”的美称。确实,在世界上许多经济发达的国家中,生产制造业的产值在国民生产总值和吸收就业人数方面所占的比例一直在逐步缩小,而其他行业(如服务行业)的比例则在逐步增长。但就英国的情况来看,其生产制造业产值的下降速度却比其他国家快得多。它在世界制造业产值方面所占的比重不仅继续相对地无情地下降,而且在绝对地下降。更令人震惊的是,英国制成品在英国对外贸易中的地位也发生了突变。我们可能难以证实《经济学人》的下述说法:“1983年以后,英国在外贸收支方面一直处于赤字逆差状态,这是自罗马人入侵英国以来首次发生的情况。”尽管如此,事实却是,甚至在20世纪50年代末期,英国制成品的出口也相当于进口的3倍,而现在,那种出超的时代已经一去不复返了。而且,失业率的上升不仅发生在较老的产业部门,也发生在“新兴”的高科技企业中。

If the fall in Britain’s manufacturing competitiveness is a century-old tale,100 it has clearly been accelerated by the discovery of North Sea oil, which while producing earnings to cover the visible trade gap has also had the effect of turning sterling into a “petrocurrency,” sending its value to unrealistically high levels for a while and making many of its exports uncompetitive. Even when the oil runs out, causing sterling to decline further, it is not at all clear that that would ipso facto lead to a revival in manufacturing: plant has been scrapped, foreign markets lost (perhaps permanently), and international competitiveness eroded by higher than average rises in unit labor costs. Britain’s shift into services is somewhat more promising, but it nonetheless remains as true here as in the United States that many services (from window cleaning to fast food) neither earn foreign currency nor are particularly productive. Even in the expanding, high-earning fields of international banking, investment, commodity dealing, and so on, it seems clear that the competition is, if anything, more intense—and in the past thirty years “Britain’s share of world trade in services has fallen from 18 percent to 7 percent. ”101 As banking and finance become a global business, increasingly dominated by those (chiefly American and Japanese) firms with massive capital resources in New York and London and Tokyo, the British share may diminish further. Finally, future developments in telecommunications and office equipment are already suggesting that white-collar jobs may soon follow the path already trodden by blue-collar workers in the West.

如果说英国生产制造业竞争力的下降已有一个世纪的历史,那么在发现了北海石油之后,其下降速度显然又加快了。北海的石油虽然可以使英国增加收入来弥补可见的贸易逆差,但也具有以下作用:使英国货币转换为“石油货币”,暂时使英镑值升至异乎寻常的高水平,结果使其许多出口商品失去了竞争力。甚至在北海石油开采完,英国货币币值不断下降的时候,我们也无法断定下述事实能否导致生产制造业出现某种复兴:工厂已被拆除,外国市场已经丧失(可能是永久丧失),高于平均水平的单位劳动力费用上升,致使其商品的国际竞争能力下降。英国大力发展服务性行业可能有某种较好的前景,但充其量也只能像美国那样。在美国,许多服务性行业(从擦窗户到提供快餐)既不能赚取外汇,更不能生产产品。甚至在国际金融、投资、商品交易等不断发展的高收入领域,也似乎可以明显地看出竞争更加激烈。在过去30年,英国在世界服务性行业的贸易中所占比重,已由18%降至7%。由于银行业和金融业已变成全球性行业,且这类行业越来越严格地受到纽约、伦敦和东京拥有巨资的企业(主要是美国和日本的企业)的控制,英国所占的份额可能越来越小。最后,由于电信系统和办公设备的进一步现代化,白领职员的工作可能像美国蓝领工人的工作那样,变得机会越来越少。

None of this, one hopes, portends a cataclysm. A general growth in world output and trade would help to keep the British economy afloat, even if its share of the whole gently declined and its per capita GNP was steadily being overtaken by many more nations, from Italy to Singapore. The decline could intensify, if a change of government led to large increases in social spending (rather than productive investment), higher taxation levels, a drop in business confidence, and a flight from sterling; it might slow down, with a government which adopted a less strict monetary policy, evolved a coherent “industrial strategy,” and cooperated with fellow Europeans in marketable (and nonprestige) ventures. It also may be true, as one economist maintains,102 that British manufacturing is now altogether leaner, fitter, and more competitive, having undergone an “industrial renaissance. ” But the auguries for a spectacular turnaround are not good; the relative immobility and lack of training in the labor market, the high unit costs, and the comparative smallness of even the largest British manufacturing firms are very considerable handicaps. The output of engineers and scientists is still dismally low. Above all, there is the poor level of investment in R&D: for every $1 spent in Britain on R&D in the early 1980s, $1. 50 was spent in Germany, $3 in Japan, and $8 in the United States—yet 50 percent of that British R&D was devoted to nonproductive defense activities, compared with Germany’s 9 percent and Japan’s minuscule amount. 103 By contrast with its chief rivals (except the United States), British R&D is both much less related to industry’s needs and much less paid for by industry itself.

人们希望,所有这一切都不是社会巨变的先兆。世界生产量和贸易额的普遍增长,有助于英国经济保持活力,即使它在整个世界生产量中所占的比重缓慢下降,它的人均国民生产总值正在逐步被许多国家(从意大利到新加坡)超过。如果政府的更迭导致社会开支大增(而不是增加生产性投资)、税收加重、商界信心不足和货币发行量猛增,则这种下降的速度有可能加快。反之,如果政府实行比较宽松的货币政策,制定出系统的“工业战略”,在市场交易活动中同欧洲伙伴合作,这种下降的速度便有可能放慢。正如一位经济学家坚持认为的,情况还可能是这样的:现在英国的生产制造业整个来看更有活力、更有竞争性和适应性,已进入了一个“工业复兴”阶段。但是,预示英国经济将有巨大转变的征兆都是不利的。劳动力短缺及缺少训练、产品成本高、最大生产企业也比其他国家的小等因素,都严重阻碍了英国工业的发展。英国培养的工程师和科学家仍然很少。尤其应当指出的是,它在研究与开发方面投资很少。20世纪80年代初,英国每在研究与开发方面花1美元,联邦德国就花1.5美元,日本花3美元,美国花8美元。而且,英国的研究与开发费用50%用于非生产性的国防事业。相比之下,联邦德国才占9%,日本则更微不足道。同主要竞争对手(美国除外)相比,英国的研究与开发工作既与工业部门的需要严重脱节,又没有得到工业部门的大力资助。

The large proportion devoted to defense-related R&D brings us onto the other horn of the British dilemma. If it was an unambitious, obscure, isolated, pacific state, its slow industrial anemia would be a pity—but irrelevant to the international power system. Yet the fact is that, although much shrunken from its Victorian heyday, Britain still remains—or claims to be—one of the leading “midsized” Powers of the globe. Its defense budget is the third- or fourth-largest (depending upon how one measures China’s total), its navy the fourth-largest, its air force the fourth-largest104—all of which, it might be thought, is significantly out of proportion to its geographical size (a mere 245,000 square kilometers), its population (56 million) and its modest, declining share of world GNP (3. 38 percent in 1983). Furthermore, despite its imperial sunset, it still has very extensive strategical commitments abroad: not only in the 65,000 troops and airmen in Germany as its contribution to NATO’s Central Front, but also in garrisons and naval bases across the globe—Belize, Cyprus, Gibraltar, Hong Kong, the Falklands, Brunei, the Indian Ocean. Despite all the premature announcements, it is still not one with Nineveh and Tyre. 105

英国把很大一部分资源用于与防务有关的研究与开发工作,这使我们看到了英国处于困境的另一个原因。如果英国是一个没有雄心壮志、茫然若失、奉行孤立主义政策、安于现状的国家,那么它的工业复兴患了慢性贫血症只能说是一件憾事,而与国际力量体系无关。但事实却是,尽管英国自维多利亚全盛时期以来国力大减,但它仍然是(或者自称是)一个世界第一流的“中等”强国。它的国防预算在世界上居第三或第四位(这要看怎样计算中国的国防预算总额),海军和空军都在世界上居第四位。人们可以认为,所有这一切与它的国土面积(仅有24.5万平方公里)、人口(5600万)和在世界生产总值中所占的比重(1983年为3.38%)不断下降的国民生产总值很不相称。而且,尽管大英帝国已如西山落日,它在国外仍然承担着大量战略义务:不仅为保卫北约中央战线在联邦德国驻有陆、空军部队6.5万人,而且在全球各地(如伯利兹、塞浦路斯、直布罗陀、中国香港、福克兰群岛、文莱、印度洋)驻扎部队,拥有海军基地。尽管英国早就多次发表过撤军声明,但迄今仍然没有出现任何一个尼尼微和泰尔[7]。

This divergence between Britain’s shrunken economic state and its overextended strategical posture is probably more extreme than that affecting any other of the larger Powers, except Russia itself. It therefore finds itself particularly vulnerable to the fact that weapon prices are rising 6 to 10 percent faster than inflation, and that every new weapon system is three to five times costlier than that which it is intended to replace. It is made the more vulnerable in consequence of domesticpolitical constraints upon defense spending; while Conservative administrations feel it necessary to contain arms spending in order to reduce the deficit, any alternative regime would feel inclined to chop defense expenditures in absolute terms. Quite apart from this political dilemma, however, there looms for Britain a fundamental and (soon) unavoidable choice: either to cut allocations to all of the armed services, placing each of them in a less than effective state; or to cut some of the nation’s defense commitments.

英国衰落的经济和过大的战略企图之间存在的不协调性,比其他任何大国(苏联除外)都更加严重。因此,它感到下述情况使自己深受其害:武器的价格正在以比通货膨胀还高6%~10%的速度上升,每种新式武器都比它打算替换的武器贵3~5倍。由于国内政治力量对国防开支的制约,英国变得更加脆弱。虽然保守党政府认为必须限制军备开支,以减少赤字,而任何接替它的政府都可能倾向于大砍国防费用。但是,除了这种政治上的困境外,英国不久将不可避免地面临下述重大基本抉择:或者削减分配给军队各部门的资源,使它们处于无法发挥作用的状态;或者部分削减国家的防务义务。

Yet as soon as that proposition is stated, the obstacles emerge. Command of the air is taken to be axiomatic (hence the RAF’s superior budget), even while the cost of new Euro-fighters is spiraling out of sight. By far the greatest British overseas commitment is to Germany and Berlin (almost $4 billion), but even now those 55,000 troops, 600 tanks, and 3,000 other armored vehicles are, despite high morale, underprovisioned. However, any reduction in the size of the BAOR (British Army on the Rhine) or fancy-footwork scheme to keep half the troops in British rather than German garrisons is likely to trigger off such political repercussions— from German grief, to Belgian emulation, to American annoyance—that it could be totally counterproductive. A second alternative is to reduce the size of the surface fleet—the Ministry of Defence solution of 1981. until the Falklands crisis upset that scheme. 106 But while such an alternative probably has the most advocates in Whitehall’s corridors of power, it looks ill-timed in the face of Russia’s rising naval challenge and the increasing American emphasis upon NATO having an “out-ofarea” thrust. (And it is certainly a contradiction for the advocates of enhancing NATO’s conventional forces in Europe to agree to reductions in the alliance’s second-largest fleet of Atlantic escorts. ) A more possible candidate for “cuts” would be Britain’s expensive and (while emotionally understandable) vastly overextended commitments in the Falkland Islands: but even that retrenchment would probably only postpone a longer decision for several years. Finally, there is the investment in the very expensive Trident submarine-based ballistic-missile system, the costs of which seem to rise month by month. 107 Given the Conservative government’s enthusiasm for an advanced and “independent” deterrent system—not to mention the way in which the Trident boats may actually be altering the overall nuclear balance (see below, p. 506)— that decision is only likely with a radical change of administration in Britain, which in turn might throw more than future defense policy into question.

可是,只要上述建议一提出,障碍马上就会出现。掌握制空权被认为是不言而喻的事(因此皇家空军的预算多于其他军种),甚至在新式欧洲战斗机的成本螺旋式飞速上升的时候,也是如此。显然,英国承担的最大海外义务是在联邦德国和柏林驻军(每年几乎耗资40亿美元)。但是,甚至到1987年驻在那里5.5万人的陆军部队、600辆坦克、3000辆其他装甲车辆,却仍然感到供应不足,尽管部队士气很高。然而,对英国莱茵陆军的规模作任何削减,或采取巧妙的策略把一半部队部署在英国而不是全驻在联邦德国,都势必要引起这样一些政治反响:联邦德国忧虑,比利时效法,美国不高兴。总之,这对北约不会产生一点儿好作用。第二种办法是削减水面舰队的规模。这是1981年英国国防部计划执行的方案,但因后来发生了福克兰群岛危机而夭折了。尽管对这项方案在白厅的权力机构中有最积极的支持者,但出台的时机不好——恰恰在苏联海军的挑战日益严重和美国进一步强调北约各国军队应有“在本区以外”推进的能力之际(主张加强北约欧洲常规部队的人士肯定不同意削减北约在大西洋上的第二支最大舰队的实力)。在削减兵力方面,另一个比较切实可行的方案是,英国减少在福克兰群岛承担的过多耗资(虽然从感情上说可以理解)、不堪重负的义务。但是,甚至这种“削减”的决定,也可能要推迟好几年才能做出。最后一点是,对耗资巨大的“三叉戟”潜射弹道导弹系统的投资,似乎仍在逐月增加。鉴于保守党政府热衷于建设一支先进的、“独立的”威慑力量(而且认为“三叉戟”潜艇还可能改变整个核力量对比格局),要做出削减核潜艇投资的决定,恐怕只有在英国出现根本的政府更迭时才有可能,而那样做反过来又可能使未来的防务政策产生更多的问题。

At the end of the day, however, the awkward choice is there. As the Sunday Times has put it, “Unless something is done soon, this country’s defense policy will increasingly consist of trying to do the same job with less money, which can only be bad for Britain and NATO. ”108 This leaves the politicians (of any party) with the alternative of reducing certain commitments, and enduring the consequences thereof; or of increasing defense expenditures still further—and Britain spends proportionately more (5. 5 percent of GNP) than any other European NATO partner except Greece—and thereby reducing its own investment in productive growth and its long-term prospects for an economic recovery. As with most decaying Powers, there is only a choice of hard options.

然而,当走到这一步时,采取任何办法都很难解决问题。正如《星期日泰晤士报》指出的:“除非马上采取措施,这个国家的防务政策将越来越倾向于用更少的钱办同样的事情,而这样做只能给英国和北约带来害处。”这就使英国(任何政党的)政治家们只能在下面两种方案中做出抉择:要么削减海外义务,并承担因此而产生的后果,要么进一步增加国防开支[英国的国防开支(占其国民生产总值的5.5%)比任何北约欧洲成员国(希腊除外)都多],从而减少生产性投资,使实现经济复兴的远期前景更加暗淡。如同衰落中的大多数强国一样,英国做出任何抉择都是困难的。

The same dilemma confronts Britain’s neighbor across the Channel, even if that has been concealed by the lack of sustained domestic questioning of France’s defense policy, and by a significantly better (if still flawed) economic performance since the 1950s. At the end of the day, Paris, like London, has to grapple with the problem of being only a “midsized” Power with extensive national interests and overseas commitments, the defense of which is coming under steadily increased pressure from escalating weapon costs. 109 While its population is the same as Britain’s, its total GNP and its per capita GNP are larger. The French produce more cars and more steel than the British and have a very large aerospace industry. Unlike Britain, France remains heavily dependent upon imported oil; on the other hand, it still runs a considerable surplus in agricultural goods, which are heavily subsidized by the EEC. In a number of significant high-technology fields— telecommunications, space satellites, aircraft, nuclear power—the French have shown a strong commitment to keeping abreast with worldwide competition. If France’s economy was badly dented by the Socialist administration’s dash for growth in the early 1980s (just when all its major trading partners were retrenching fiscally), the stricter policies which followed seem to have reduced inflation, cut the trade gap, and stabilized the franc, all of which ought to allow for a resumption in French economic growth.

英国在英吉利海峡另一边的邻国——法国——也同样处于困境之中,尽管它的困境因为国内对法国防务政策没有连续不断的批评和其经济情况自20世纪50年代以来一直甚佳(并不是说一点儿问题也没有)而被掩盖了起来。归根结底,同英国一样,法国也不得不妥善处理这样一个问题:它仅仅是一个“中等”强国,但拥有广泛的国家利益和海外义务,而武器造价越来越高使保卫国家利益和承担海外义务变得日益困难。尽管它的人口总数同英国一样,但它的国民生产总值和人均国民生产总值却高于英国。法国生产的汽车和钢比英国多,并拥有规模很大的航空航天工业。与英国不同,法国仍必须大量进口石油。另外,它的农产品自给有余,欧共体为其提供了大量补贴。在许多重要的高技术领域,如电子通信、空间卫星、飞机、核动力等,法国决心使自己的产品在世界市场上保持竞争能力。20世纪80年代初(正当法国的主要贸易伙伴国采取财政紧缩政策的时候),法国的经济因社会党政府一味追求发展而受到严重损害。此后,它执行得更严格的政策似乎已使通货膨胀率下降,贸易赤字缩小,法郎币值稳定了下来。所有这一切应当使法国经济的发展趋势得到恢复。

But whenever France’s economic structure and prospects are compared with those of its powerful neighbor across the Rhine—or with Japan’s—the precariousness shows through. While France is still spectacularly adroit in exporting fighter aircraft, wines, and grain, it “remains relatively weak in selling run-of-the-mill manufactured goods abroad. ”110 Too many of its customers have been unstable Third World countries that order lavish projects like dams or Mirages and then have difficulty paying for them; by contrast, the “import penetration” of industrial goods, automobiles, and electrical appliances into France indicates broad fields where it is not competitive. Its trade deficit with West Germany grows year by year and, since French prices always rise faster than those in Germany, will in all probability lead to further devaluations of the franc. The northern landscape of France is still scarred with decaying industries—coal, iron, steel, shipbuilding—and much of its automobile industry is also feeling the strain. And while the new technologies seem full of promise, neither can they absorb France’s many unemployed nor are they receiving the levels of investment necessary to keep pace with German, Japanese, and American technologies. More worrying still for a country as economically (and, of perhaps greater import, psychologically) attached to agriculture is the looming crisis of global overproduction of grains, dairy produce, fruit, wine, etc. —with its increasing strain upon French and EEC budgets if farm-support prices are maintained and its threat of social unrest if prices are cut. Until a few years ago, Paris could rely upon Community funds to aid in restructuring agriculture; now, most of that cash is likely to go to the peasants of Spain, Portugal, and Greece. All this may leave France without the capital resources necessary for a much larger R&D effort and for sustained, high-tech-based growth over the next two decades.

但是,每当把法国的经济结构和前景同莱茵河彼岸强大的邻国,或同日本进行比较时,它的问题就暴露无遗了。虽然法国仍然大量出口战斗机、葡萄酒和谷物,但它“在向国外销售普通制成品方面却一直有问题”。它的许多主顾都是形势不稳定的第三世界国家,同这些主顾签订的合同都是耗资巨大的项目,如修建水坝,或定购“幻影”式飞机等。但合同签订后,它们又没有支付能力。相比之下,许多外国工业品、小轿车和家用电器产品“打入”法国表明,在一些重要领域,法国产品没有竞争力。它同联邦德国的贸易逆差在逐年扩大。而且,由于法国的物价总是比联邦德国增长得快,这很可能导致法郎进一步贬值。法国北部的情况仍然令人担忧,煤炭、钢铁和造船等工业很不景气;它的很大一部分汽车工业也感到压力很大。虽然新技术似乎给法国人带来了希望,但它们不能吸收大量失业者,也不能吸收大量的投资,以便与联邦德国、日本和美国技术的发展保持同步。在一个经济上离不开农业的国家看来,更令人忧虑的是全球谷物、奶制品、水果、酒等农产品生产过剩造成的危机。如果继续执行对农产品实行补贴的价格政策,法国和欧共体受到的压力将越来越大;如果削减价格补贴,则可能会引起社会动乱。直到几年前,巴黎还能够依赖欧共体提供的资金来帮助它改善农业结构。现在,这笔资金的大部分很可能要跑到西班牙、葡萄牙和希腊农民的腰包中去。所有这一切可能使法国在今后20年内没有必要的资金来大规模开展研究与开发工作,并使以高技术为基础的国民经济获得持续增长。

It is in this larger context, of fixing priorities for France’s future, that one needs to view the debate over national defense policy. In many ways, there is much that is impressive about French strategy, and military actions, in recent times. Recognizing (and assertively voicing) the increasing doubts about the credibility of the American strategic nuclear deterrent, France has provided itself with its own “triad” of delivery systems for use in the event of Soviet aggression. By keeping in its own hands every aspect of its nuclear deterrent (from production to targeting), and by insisting that its entire force of missiles will be loosed at Russia if deterrence fails, Paris feels it has a more certain way of holding the Kremlin in check. At the same time, it has maintained one of the largest land armies and has a substantial garrison in southwestern Germany and a commitment to come to the Federal Republic’s aid; while being outside the NATO command structure, and thus able to proffer an independent “European” voice on strategic issues, it has not dislocated the military need for reinforcing the Central Front in the event of a Russian attack. The French have also maintained an extra-European role and—by means of occasional military interventions overseas, the presence of their garrisons and advisers in Third World countries, and their successful arms-sales policy—offered an alternative influence (and source of supply) to either the USSR or the United States. If this has sometimes irritated Washington—and if French nuclear testing in the South Pacific has rightly annoyed the countries of that region—then Moscow in its turn can hardly be comforted by the various and sometimes unpredictable displays of Gallic independence. Furthermore, since both the right and the left in France support the idea of the nation’s playing a distinct role abroad, French claims and actions for that purpose do not provoke the domestic criticism which would occur in virtually all other Western societies. All this had led foreign observers (and, of course, Frenchmen themselves) to describe their policy as logical, hard-nosed, realistic, and so on.

正是在法国未来必须确定发展的轻重缓急这一范围更大的背景下,人们需要研究一下有关法国国防政策的不同意见。近几年来,法国的战略及其军事行动在许多方面给人们留下了极为深刻的印象。由于认识到(以及口头上断言)美国战略核威慑力量的可靠性越来越令人怀疑,法国已单独建立起自己“三位一体”的发射系统,以备在苏联发动侵略战争时使用。由于自己生产核武器并掌握核威慑力量的使用权,坚持一旦威慑失灵就动用自己的整个导弹部队打击苏联,巴黎感到自己更有把握遏制克里姆林宫的侵略。与此同时,它拥有一支庞大的地面部队,在联邦德国西南部有一支最强大的驻军,并承担了一旦联邦德国要求就提供援助的义务。尽管它不在北约指挥系统之内,因而对战略问题能发表“欧洲人”的独立见解,但它并没有拒绝一旦苏联发动进攻即增援中央战线的军事需要。法国在欧洲以外地区还可发挥应有的作用。通过偶尔在海外采取军事干涉行动,在第三世界国家保持驻军和派出顾问,以及成功地推行军火销售政策,它还能(作为供应国)对苏联或美国施加一定影响。虽然这一切有时使华盛顿不快,虽然法国在南太平洋的核试验使该地区的国家深感不安,但苏联对于高卢人闹独立性的种种(有时是无法预料的)表现也不会感到满意。而且,由于法国右翼和左翼人士都支持本国在国外发挥突出作用,因而法国政府为此目的所造的舆论和采取的实际行动也不会引起国内的批评,而在其他几乎所有西方国家则不然。所有这一切促使外国观察家(当然也包括法国人自己)把法国的政策说成是符合逻辑的、不感情用事的、切实可行的,等等。

Yet the policy itself is not without its problems—as some French commentators are beginning openly to admit111—and must cause the historically minded to recall the gap which existed between the theory and the reality of France’s defense policy prior to 1914 and 1939. In the first place, there is a great deal of truth in the cold observation that all of France’s posturings of independence have taken place behind the American shield and guarantee to western Europe, both conventional and nuclear. A Gaullist policy of assertiveness was only possible, Raymond Aron pointed out, because for the first time in this century France was not in the front line. 112 But what if that security disappears? That is, what if the American nuclear deterrent is admitted to be non-credible? What if the United States, over time, steadily pulls back its troops, tanks, and aircraft from Europe? Under certain circumstances, both of those eventualities might be seen as welcome. Yet, as the French themselves admit, they can hardly appear so in the light of Moscow’s recent policies: steadily building up its own nuclear and European-based conventional forces to excessive levels, keeping a tight hold upon its eastern European satellites, and launching “peace offensives” designed perhaps particularly to wean the West German public out of the NATO alliance and into neutralism. Many of the signs of what has been termed France’s “New Atlanticism”113—a stiff er tone toward the Soviet Union, criticism of neutralist tendencies among the German Social Democrats, the FrancoGerman agreement for the forward deployment in Germany (possibly with tactical nuclear weapons) of the Force d’Action Rapide, the closer links with NATO114—are obvious consequences of French concern about the future. Until Moscow changes, Paris is bound to worry that the USSR might move into western Europe when (or even before) the United States has moved out.

但是,正如某些法国评论家开始公开承认的那样,法国的政策也并不是没有问题的。它的政策使了解历史情况的人自然而然地回想到了1914年和1939年以前法国防务政策在理论与现实之间的差距。首先,通过冷静的观察就会发现,法国的所有独立姿态都是在美国向西欧做出保护与保证(包括常规力量和核力量方面的保证)的前提下做出的。雷蒙·阿隆指出,高卢人的强硬政策之所以有可能得到执行,只是因为法国在20世纪第一次没有处于最前线。但是,如果美国提供的安全保证不复存在,那又会是一种什么情景呢?也就是说,如果大家都认为美国的核威慑力量靠不住,如果美国逐步从欧洲撤回自己的部队、坦克和飞机,那又会怎样呢?在某些场合下,出现上述两种情况,都可能受到欢迎。可是,正如法国人自己所承认的,他们对出现上述情况决不会感到高兴,因为苏联实行的政策是:逐步把自己的核力量与驻欧洲的常规部队加强到无比强大的水平,对其东欧卫星国实行严密的控制,发动旨在使联邦德国公众要求脱离北约组织联盟和实行中立主义的“和平攻势”。那些表明法国实行所谓“新大西洋主义”的许多迹象,皆为法国对未来表示担心的明证。“新大西洋主义”强调:对苏联采取更加强硬的立场;批评德国社会民主党人中的中立主义倾向;法德达成协议,在联邦德国前沿部署法国快速行动部队(还可能包括战术核武器);同北约联系更紧密。在苏联改弦更张之前,法国必然要对美国从欧洲撤军后(甚至在撤军前)苏联可能向西欧进军深感忧虑。

But if that threat became more likely, what could France do about it in practical terms? Naturally, it could increase its conventional forces still further, moving toward the creation of an enhanced Franco-German army strong enough to hold off a Russian assault even if U. S. forces were diminished (or even absent). In the view of people like Helmut Schmidt,115 this is the logical extension not only of the Paris- Bonn entente but also of international trends (e. g. , the weakening of American capacities). There are all sorts of political and organizational difficulties in the way of such a scheme—ranging from the possible attitude of a future left-of-center German administration, to questions of command, language and deployment, to the touchy issue of French tactical nuclear weapons116—but in any event such a strategy is likely to founder upon one insuperable reef: lack of money. France is currently spending about 4. 2 percent of its GNP upon defense (compared with the United States’ 7. 4 percent and Britain’s 5. 5 percent), but given the delicate state of the French economy, that percentage cannot be increased by very much. Moreover, France’s independence in atomic-weapons development means that its nuclear strategic forces absorb up to 30 percent of the defense budget, far more than elsewhere. What is left is not enough for the AMX battle tank, advanced aircraft, the new nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, “smart” battlefield weapons, and so on. While certain increases in the French armed forces may be likely, that could not possibly satisfy all requirements. 117 Just as in Britain’s case, therefore, the French are being faced with the awkward choice of either eliminating some weapon systems (and roles) entirely or forcing economies upon all of them.

如果出现上述威胁的可能性加大,法国在实际上能够采取什么行动呢?当然,它可以进一步扩充常规部队,采取步骤建立一支强大的、在美军减少甚至不复存在的情况下也足以制止苏军进攻的法德联军。在联邦德国政治家赫尔穆特·施密特等人看来,这不仅是巴黎-波恩协约的合乎逻辑的发展,也是国际形势(例如美国兵力削弱)不断发展的结果。要执行这样一种计划,肯定会遇到种种政治上和组织上的困难,如今后中间偏左的联邦德国政府可能采取的态度、指挥、语言和部署问题,以及非常棘手的法国战术核武器的使用问题。但不管怎样,这项计划肯定会撞在无法规避的资金缺乏这个暗礁上。在20世纪80年代,法国用在防务上的开支约占国民生产总值的4.2%(相比之下,美国占7.4%,英国占5.5%)。但是,鉴于法国经济的脆弱性,这一比重不可能再增加很多。而且,法国独立发展原子武器还意味着,它的战略核部队的开支在国防预算中所占的比重达30%,这一数字远远超过任何其他国家。因此,剩下来的资源便不够用来置办AMX作战坦克、先进的飞机、新型核动力航空母舰,以及各种“超级”战斗武器等。法国武装部队虽然有可能在一定程度上得到扩充,但这满足不了所有需要。所以,正像英国所面临的情况,法国也面临着下述困难的抉择:要么完全停止研制某些武器系统,要么使国民经济军事化。

Equally worrying are the doubts being raised about France’s nuclear deterrent, both at the technical and the (related) strategical level. Parts of the triad of French nuclear weaponry—the land-based missiles, and especially the aircraft—suffer from deterioration over time and even their costly upgrading and modernization may not keep pace with newer weapons technology. 118 This problem may become particularly acute if significant breakthroughs occur in American Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) technology, and if the Russians in their turn develop a much larger system of ballistic-missile defense. Nothing is more disturbing, from the French viewpoint, than the two superpowers enhancing their potential invulnerability while Europe remains exposed. As against this, there is the significant buildup of the French submarine-launched ballistic-missile system (discussed below, p. 506). However, the general principle remains: advanced technology could render useless existing types of weaponry, and certainly will make the cost of any replacements much more expensive. In any case, the French are caught in the same trap of credibility as all of the other nuclear Powers. If Paris thinks it increasingly unlikely that the United States would risk a strategic nuclear exchange with the USSR because the German frontier had been invaded, how likely is its own promise to “go nuclear” on behalf of the Federal Republic? (The West Germans hardly believe it. ) Even the Gaullist tradition of defending the “sanctuary” of France by firing off all its missiles at Russia hangs upon the unproven assumption that the French people prefer obliteration to a possible (or likely) defeat by conventional means. “Tearing an arm off the Russian bear” has always sounded like a good phrase, until it is remembered that one will certainly be devoured by the bear; and that Russia’s own antimissile defenses may limit the damage it will suffer. Obviously, the official posture of French nuclear strategy is not going to be altered soon, if at all. But it is worth wondering how realistic it is, should the East-West balance worsen and the United States weaken. 119

同样令人忧虑的是,在技术和战略方面人们对法国核威慑力量作用的怀疑。法国的部分“三位一体”核武器系统(陆基导弹,尤其是飞机)已经过时,甚至进行耗资巨大的改装和现代化改进也可能赶不上更新的武器技术的发展。如果美国战略防御计划在技术上获得重大突破,如果苏联也建立起庞大的弹道导弹防御体系,这个问题将变得更为严重。在法国人看来,没有什么比两个超级大国不断加强自身潜在的军事力量而让欧洲继续处于易受攻击的状态更令人不安的了。针对这种情况,法国已大大加强了它的潜射弹道导弹系统。可是,有一条法则仍在起作用:先进的技术不仅可以使现有武器系统变得毫无用处,而且肯定会使任何更新武器系统造价更加昂贵。毫无疑问,德国也像所有其他核大国一样对核威慑的可靠性产生了怀疑。如果巴黎认为,美国越来越不可能因为联邦德国边境受到侵犯而甘愿冒险同苏联进行一场战略核交锋,法国怎么可能为了联邦德国的利益而履行自己的“诉诸核武器”的允诺呢?(就连联邦德国人也很难相信这一点。)即使通过向苏联发射全部导弹来保卫法国“圣殿”的高卢传统也是以这样一种未经证实的假设为前提的:法国人宁愿接受被常规手段击败的灭亡。“砍掉苏联熊一条臂膀”这句话说起来中听,但在人们想到他们肯定要被苏联熊吞食和苏联因其反导防御体系可能使损害减少之后感觉就不一样了。显然,法国官方的核战略不会很快改变,更不用说完全改变。但是,人们不禁要问:如果东西方力量对比进一步恶化,美国的力量减弱,法国的核战略还切实可行吗?

France’s problem, then, is that so many demands are pressing upon its own modest national resources. Given demographic and structural-economic trends, the high share of national income consumed by social security is likely to continue, and probably increase. Large funds may soon be needed for the agricultural sector. At the same time, the modernization of the armed forces requires substantial amounts of money. Yet all of these have to be balanced against—and take away from—the pressing need for vastly enlarged investment in R&D and in advanced industrial processes. If it cannot allocate the monies necessary for the last-named purpose, it will over time put into jeopardy the prospects of affording defense, social security, and all the rest. Obviously this dilemma is not France’s alone, although it is the French above all who have argued for a distinctively “European” position on international economic and defense issues—and who therefore most clearly articulate European concerns. For this reason, too, it is Paris which has usually taken the lead in initiating new policies—deepening Franco-German military ties, producing European Airbuses and satellites, and so on. Many of these schemes have met with skepticism among France’s neighbors at this Gallic fondness for bureaucratic planning and prestige endeavors, or with the suspicion that French companies are likely to be awarded the lion’s share of Euro-funded projects. Other schemes, however, have already proved their worth or seem to hold a rich promise.

因此,法国的问题是:各方面的需求很多,而国家资源有限,负担不起。鉴于人口和经济发展趋势前景不佳,法国防务消耗的国民收入将继续占很大比重,并且还可能进一步增加。法国可能很快不得不为农业部门拨出大量资金。同时,武装部队的现代化也需要大量金钱。但是,在考虑所有这些需求时,不应忘记还要向研究与开发领域和先进的工业部门大量投资的迫切需求。如果不为后者分配足够的资金,经过一段时间,法国的国防建设、社会安全和所有其他领域的前景就会变得暗淡起来。尽管不只是法国面临这一困难,但法国人主张在国际经济交往和防务方面欧洲人应该有“欧洲人”的立场,而且显然只有法国人能诉说欧洲人的苦衷。正是由于这一点,巴黎才常常率先提出新政策(如加强法德军事联系,生产欧洲“空中客车”和卫星等)。搞这些项目造成的后果是:法国的邻国对高卢人喜欢独断专行地制订计划和争权夺利的做法产生了顾虑,对法国公司有可能在欧洲提供资金的项目中获得最大份额深表疑虑。但是,其他项目都已证明是值得做的,而且大有前途。

Europe’s “problems” are, of course, more than those considered here: they include aging populations and aging industries, ethnic discontents in the inner cities, the gap between the prosperous north and the poorer south, the political/linguistic tensions in Belgium, Ulster, and northern Spain. Pessimistic observers also occasionally allude to the possibility of a “Finlandization” of certain European states (Denmark, West Germany), which would then become dependent upon Moscow. Since that development could only follow from a leftward political shift in the countries concerned, it is difficult to estimate its likelihood. As it is, if one considers Europe—as represented chiefly by the EEC—as a power-political unit in the global system, the most important issues it faces are clearly those discussed above: how to evolve a common defense policy for the coming century which will be viable even in what may be an era of significant change in the international power balances; and how to remain competitive against the very formidable economic challenges posed by new technology and new commercial competitors. In the case of the other four regions and societies examined in this chapter, it is possible to suggest what changes are likely to occur over time in their present position: that Japan and China will probably see their status in the world enhanced, and that the USSR and even the United States will see theirs eroded. But Europe remains an enigma. If the European Community can really act together, it may well improve its position in the world, both militarily and economically. If it does not—which, given human nature, is the more plausible outcome—its relative decline seems destined to continue.

诚然,欧洲的“问题”远不只这里讲到的这些,还有人口老化,工业设备陈旧,内地城市存在的种族矛盾,繁荣的北方和贫穷的南方之间的差别,比利时、北爱尔兰和西班牙北部因政治和语言问题而引起的紧张局势。持悲观态度的观察家们还偶尔提及某些欧洲国家(丹麦、联邦德国)可能“芬兰化”,并认为如果发生这种情况,它们就会倒向苏联。由于上述情况只有在有关国家的左派政治力量上台之后才能出现,我们现在还难以估计其可能性。即使发生了这种情况,如果人们把欧洲(其代表主要是欧共体)作为全球系统的一个政治力量单位来考虑,它面临的最重要的问题显然是我们上面提及的那些:如何为下一个世纪制定一项共同的防务政策,这项政策甚至在国际力量对比可能发生重大变化的时候,也具有活力;如何在面临新技术和新商业竞争对手的严重挑战的情况下保持竞争力。从本章所论及的其他4个国家的情况看,我们可推断出今后可能发生下述变化:日本和中国在世界上的地位将可能得到加强,苏联甚至美国的地位将可能受到削弱。然而,欧洲却仍然是一个谜。如果欧共体能够真正团结一致地行动,它很可能提高自己在世界上的地位——不管是军事方面的,还是政治方面的。反之,如果人的不团结本性导致出现一种不利的结局,则欧洲衰落的趋势就一定会继续下去。