The Soviet Union and Its “Contradictions”

矛盾重重的苏联

The word “contradiction” in Marxist terminology is a very specific one, and refers to the tensions which (it is argued) inherently exist within the capitalist system of production and will inevitably cause its demise. 120 It may therefore seem deliberately ironic to employ the same expression to describe the position in which the Soviet Union, the world’s first Communist state, now finds itself. Nevertheless, as will be described below, in a number of absolutely critical areas there seems to be opening up an ever-widening gap between the aims of the Soviet state and the methods employed to reach them. It proclaims the need for enhanced agricultural and industrial output, yet hobbles that possibility by collectivization and by heavyhanded planning. It asserts the overriding importance of world peace, yet its own massive arms buildup and its link with “revolutionary” states (together with its revolutionary heritage) serve to increase international tensions. It claims to require absolute security along its extensive borders, yet its hitherto unyielding policy toward its neighbors’ own security concerns worsens Moscow’s relations—with western and eastern Europe, with Middle East peoples, with China and Japan—and in turn makes the Russians feel “encircled” and less secure. Its philosophy asserts the ongoing dialectical process of change in world affairs, driven by technology and new means of production, and inevitably causing all sorts of political and social transformations; and yet its own autocratic and bureaucratic habits, the privileges which cushion the party elites, the restrictions upon the free interchange of knowledge, and the lack of a personal-incentive system make it horribly ill-equipped to handle the explosive but subtle high-tech future which is already emerging in Japan and California. Above all, while its party leaders frequently insist that the USSR will never again accept a position of military inferiority, and even more frequently urge the nation to increase production, it has clearly found it difficult to reconcile those two aims; and, in particular, to check a Russian tradition of devoting too high a share of national resources to the armed forces—with deleterious consequences for its ability to compete with other societies commercially. Perhaps there are other ways of labeling all these problems, but it does not seem inappropriate to term them “contradictions. ”

“矛盾”一词在马克思主义的术语中有其特定含义,特指资本主义生产方式所固有的矛盾,这一矛盾的发展必然导致资本主义的灭亡。因此,用这一术语描述苏联这个世界上第一个社会主义国家现在的处境,似乎是我们在故意进行冷嘲热讽。尽管如此,在许多至关重要的方面,苏联所要达到的目标与其手段之间的矛盾却在日益增大。它公开声称要增加工农业产值,但却又以集体化和僵化的国家计划来阻碍工农业的发展。它承认世界和平极其重要,但其庞大的军事力量与“革命”国家的联系及其本身的革命传统,又往往加剧了国际紧张局势。它要求绝对保证其漫长边界线的安全,但却采取不尊重邻国安全的顽固政策。这不仅恶化了它与西欧、东欧、中东国家、中国以及日本的关系,还使苏联人产生了“被包围”感和不安全感。苏联的学说承认科学技术和新的生产手段是推动事物辩证发展的动力,将不可避免地导致政治和社会变革。但是,苏联官僚主义的习惯势力、以苏联共产党的领导干部为主体的特权阶层、对自由交流知识的限制和缺乏激励个人发挥主动性的制度,这一切都使它在迎接未来的高技术革命方面处于极其不利的地位,而在日本和加利福尼亚,高科技已被大量采用。苏联共产党的领导人经常说,苏联决不能在军事上处于劣势地位,要求人民增加生产的呼吁则更多。但是,他们已清楚地认识到要调节这两个目标的关系是很困难的,要改变把过多的国家资源用于军队这一传统则更加不容易。结果,苏联削弱了自己与其他国家进行经济竞争的能力。也许可以把所有这些问题贴上别的标签,但称它们为“矛盾”似乎更为确切。

Given the emphasis in Marxian philosophy upon the material basis of existence, it may seem doubly ironic that the chief difficulties facing the USSR today are located in its economic substructure; and yet the evidence gleaned by western experts—not to mention the increasingly open acknowledgments by the Soviet leadership itself— leave no doubt that that is so. It would be interesting to know how Khrushchev, who in the 1950s confidently forecast that the USSR would overtake the United States economically and “bury” capitalism, would have felt about Mr. Gorbachev’s 1986 admissions to the 27th Communist Party Congress:

马克思主义哲学强调物质是存在的基础,但具有双重讽刺意味的是,苏联的主要困难正在于其经济结构。西方专家搜集的证据(且不说苏联领导人越来越多的公开承认)表明,情况的确如此。赫鲁晓夫在20世纪50年代曾信心十足地预言:苏联在经济上将超过美国,将“埋葬”资本主义。但他如果活到今天,听到戈尔巴乔夫先生在1986年苏共二十七大上的讲话会有何感想呢?戈尔巴乔夫说:

Difficulties began to build up in the economy in the 1970s, with the rates of economic growth declining visibly. As a result, the targets for economic development set in the Communist Party program, and even the lower targets of the 9th and 10th 5-year plans were not attained. Neither did we manage to carry out the social program charted for this period. A lag ensued in the material base of science and education, health protection, culture and everyday services.

20世纪70年代,经济困难开始出现,经济增长率明显降低。结果不仅党纲中提出的经济发展目标未能实现,甚至第九个五年计划和第十个五年计划规定的较低的目标也未能实现。这一时期,我们的社会发展计划未得到贯彻执行。科学、教育、卫生、文化和社会服务也发展缓慢。

Though efforts have been made of late, we have not succeeded in fully remedying the situation. There are serious lags in engineering, the oil and coal industries, the electrical engineering industry, in ferrous metals and chemicals in capital construction. Neither have the targets been met for the main indicators of efficiency and the improvement of the people’s standard of living. Acceleration of the country’s socio-economic development is the key to all our problems; immediate and long-term, economic and social, political and ideological, internal and external. 121

我们后来虽然进行过努力,但未能完全扭转形势。工艺技术、石油煤炭业、电机工程业、黑色金属业和化学工业的基本建设严重停滞不前。主要经济效率指标和提高人民生活水平的目标也未能达到。 因此,加速发展国民经济是解决一切近期和长远、经济和社会、政治和思想、国内和国外问题的关键。

To which it might be remarked that the final statement could have been made by any government in the world, and that the mere recognition of economic problems is no guarantee that they will be solved.

对此,我们可以这样说,世界上任何国家的政府都可发表这种声明,但仅仅承认在经济上有问题并不一定能确保他们解决这些问题。

The most critical area of weakness in the economy during the entire history of the Soviet Union has been agriculture, which is the more amazing when it is recalled that a century ago Russia was one of the two largest grain exporters in the world. Yet since the early 1970s it has needed to import tens of millions of tons of wheat and corn each year. If world food-production trends continue, Russia (and certain other socialist economies of eastern Europe) will share with parts of Africa and the Near East the dubious distinction of being the only countries which have changed from being net food exporters to importers on a large-scale and sustained way over recent years. 122 In Russia’s case, this embarrassing stagnation in agricultural output has not been for want of attention or effort; since Stalin’s death, every Soviet leader has pressed for increases in food production, in order to meet consumer demand and to fulfill the promised rises in the Russian standard of living. It would be wrong to assume that such rises have not occurred—clearly, the average Russian is much better off now than in 1953, when his situation was desperate. But what is much more depressing is that after some decades of drawing closer to the West, his standard of living is falling behind again—despite all the resources which the state commits toward agriculture, which swallows up nearly 30 percent of total investment (cf. 5 percent in the United States) and employs over 20 percent of the labor force (cf. 3 percent in the United States). Merely in order to maintain standards of living, the USSR is compelled to invest approximately $78 billion in agriculture each year, and to subsidize food prices by a further $50 billion—despite which it seems “to be moving further and further away from being the exporter it once was”123 and instead needs to pour out further billions of hard currency to import grain and meats to make up its own shortfalls in agricultural output.

从苏联的整个历史看,农业在其经济中一直是最薄弱的环节。令人不解的是,在100年前俄国却是世界两大谷物出口国之一。而自20世纪70年代初以来,苏联每年需进口数千万吨小麦和玉米。如果世界粮食生产保持目前的势头,苏联(和某些东欧社会主义国家)在近年内将步一些非洲和中东国家之后尘,从粮食纯出口国沦为粮食纯进口国。苏联农业生产陷入这种困境并不是对农业漠不关心或努力不够造成的。斯大林去世后,每一位苏联领导人都重视提高粮食产量,以满足消费者的需要,并兑现其提高人民生活水平的许诺。认为苏联人的生活水平没有提高是不对的,苏联人的平均生活水平要比(令人绝望的)1953年高得多。但令人沮丧的是,虽然国家对农业投入了大量财力、物力和人力,农业投资占国家全部投资的30%(美国只占5%),农村劳动力占全国劳动力的20%(美国仅占3%),但经过几十年的努力逐渐与西方国家接近的苏联人的生活水平又走下坡路了。仅仅要保持当时的生活水平,苏联就必须每年向农业投资约780亿美元,另加500亿美元的食品价格补贴。这将使苏联离粮食出口国的距离越来越远,将使其不得不拿出更多的硬通货来进口谷物和肉类,以弥补农业产量的不足。

There are, it is true, certain natural reasons for the precariousness of Soviet agriculture, and for the fact that its productivity is about one-seventh that of American farming. Although the USSR is often regarded as geographically rather similar to the United States—both being continent-wide, northern-hemisphere states —it actually lies much farther to the north: the Ukraine is on the same latitude as southern Canada. Not only does this make it difficult to grow corn, but even the Soviet wheat-growing regions endure far colder winters—and are subject to more frequent droughts—than states like Kansas and Oklahoma. The four years 1979– 1982 were particularly bad in that respect, and so embarrassed the government that it stopped giving details of agricultural output (although its average import of 35 million tons of grain each year provided a clue!). Even the “good” year of 1983 did not make the USSR self-sufficient—and it was followed in turn by yet another disastrous year of cold and drought. 124 Moreover, any attempt to increase production by extending the wheat acreage into the “virgin lands” is always constricted by frosts in the north and the arid conditions in the south.

苏联农业产量不稳定,且其农业产量只有美国的l/7,确实有自然条件方面的原因。虽然美苏两国在地理上有许多相似之处,都是北半球幅员广阔的国家,但苏联的纬度要高得多(乌克兰地区同加拿大南部处于同一纬度)。这种地理位置不仅不利于玉米生长,而且使小麦种植区冬季的气温比美国的堪萨斯州和俄克拉何马州冷得多,并更容易遭受旱灾的侵袭。1978~1982年的4年间,苏联的气候特别糟,以致苏联政府不得不停止宣布农业产量的具体数字(虽然苏联平均每年进口3500万吨粮食已为人们提供了一些线索)。就是在“丰收”的1983年,苏联也未能达到粮食自给,而下一年又是一个寒冷、干旱的灾年。而且,由于北方无霜期短,南方土地贫瘠,通过开垦“处女地”、扩大耕地面积来提高小麦产量的企图也很难实现。

Nevertheless, no outside observers are convinced that it is climate alone which has depressed Soviet agricultural output. 125 By far the biggest problems are simply caused by the “socialization” of agriculture. To keep the Russian populace happy, food prices are held artificially low through subsidies, so that “meat costing the state $4 a pound to produce sells for 80 cents a pound”126—which, for example, makes it cheaper for peasants to buy and feed bread and potatoes to their livestock than to use unprocessed grain. The vast amounts of state investment in agriculture are thrown at large-scale projects (dams, drainage) rather than at individual barns or up-to-date small tractors that an ordinary peasant might want. Decisions as to planting, investment, and so on are taken not by those who work the fields but by managers and bureaucrats. The denial of responsibility and initiative to the individual peasants is probably the single greatest reason for disappointing yields, chronic inefficiencies, and enormous wastage—although the wastage is clearly affected also by the inadequate storage facilities and lack of year-round roads, which causes “approximately 20 percent of the grain, fruit and vegetable harvest, and as much as 50 percent of the potato crop [to perish] because of poor storage, transportation and distribution. ”127 What could be done if the system were altered in its fundamentals—that is, a massive change away from collectivization towards individual peasant-run farming—is indicated by the fact that the existing private plots produce around 25 percent of Russia’s total crop output, yet occupy a mere 4 percent of the country’s arable land. 128

但是,各国观察家却一致认为,苏联农业停滞不前的主要原因不是气候条件,其最大的问题是农业的“社会化”引起的。为了取悦百姓,苏联政府用补贴的办法把食品价格人为地压低了,把每磅成本为4美元的肉以80美分的价格出售。其结果是,农民以购买来的面包和土豆饲养牲畜要比用自产的谷物饲养更合算。国家的农业投资主要用于大型项目(如水坝、排灌工程),而不是普通农民需要的厩棚和现代化小型拖拉机。对播种、投资等问题,在农田劳作的人无权决定,而是由管理者和官僚们决定。农民没有责任心、没有积极性,可能是农业产量低、效益低、浪费大最重要的原因。另外,由于贮存设施不足、运输设备陈旧落后和分配不及时,20%的谷物、水果和蔬菜及50%的土豆都烂掉了。如果对这一体制进行根本性的改革,把农业集体化变为个体化,其结果是不言而喻的。苏联的自留地占全国耕地的4%,但其产量却占苏联农产品总量的25%,就是最好的证明。

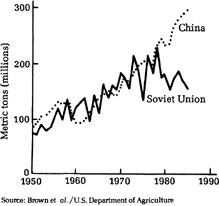

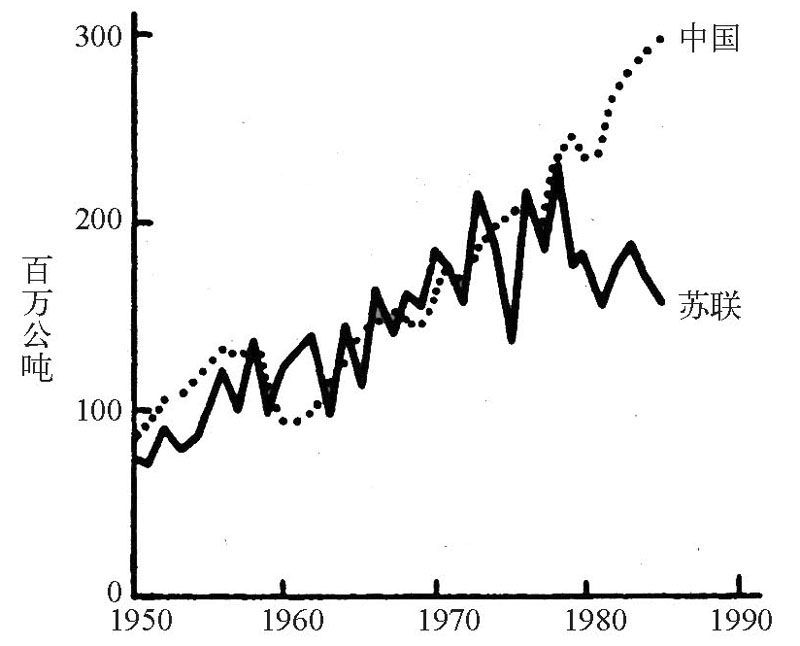

Yet whatever the noises about “reform” from the highest levels, the indications are that the Soviet Union is not contemplating following Mr. Deng’s large-scale agricultural changes to anything like the extent of China’s “liberalization” (see above), even when it is clear that Russian output is falling far behind that of its adventurous neighbor. 129

但是,无论苏联最高领导层在“改革”方面唱的调子多高,他们也不想按照邓小平的做法,进行大规模的农业改革,达到中国式的市场化程度,虽然事实很明显:苏联的农业产量大大低于它的勇于开拓的邻邦(见图3)。

Chart 3. Grain Production in the Soviet Union and China, 1950–1984

图3 1950~1984年苏联、中国粮食产量的比较

Although the Kremlin is unlikely to explain openly why it prefers the present system of collectivized agriculture despite its manifest inefficiencies, two reasons for this inflexibility stand out. The first is that a massive extension of private plots, the creation of many more private markets, and increases in the prices paid for agricultural produce would imply significant rises in the peasantry’s share of national income—to the detriment of the resentful urban population and, perhaps, of industrial investment. It would mean, in other words, the final triumph of Bukharin’s policies (which favored agricultural incentives) and the demise of Stalin’s prejudices. 130 Secondly, it would mean a decline in the powers of the bureaucrats and managers who run Soviet agriculture, and thus have implications for all of the other spheres of decision-making. While it is surely true that “individual farmers making day-to-day decisions in response to market signals, changing weather, and the conditions of their crops have a combined intelligence far exceeding that of a centralized bureaucracy, however well designed and competently staffed,”131 what might that imply for the future of the “centralized bureaucracy”? If it is correct that there is a consistent, embarrassing relationship between “socialism and national food deficits,”132 then that can hardly have escaped the Politburo’s attention. But from its own perspective, it may seem better—safer, certainly—to maintain “socialist” (i. e. , collectivized) farming even if that implies rising food imports, rather than to admit the failure of the Communist system and to remove the existing controls upon so large a segment of society.

克里姆林宫虽然不会公开解释为什么要继续坚持效益极低的集体农庄体制,但有两个原因是非常明显的。第一,如果大幅度增加自留地面积,开辟更多的自由市场,提高农产品价格,农民收入在国民收入中的比重就会大大提高。这将损害城市居民的利益,引起他们的不满,甚至可能有损于工业投资。从另一方面看,这还意味着布哈林政策(即调动农民积极性的政策)的最终胜利和斯大林路线的破产。第二,如果放弃集体农庄制,控制苏联农业的官僚和管理者们的权力就会被削弱,这将使其他行业和部门的决策者们的权力受到影响。毫无疑问,“个体农户”可根据市场信息、不断变化的气候情况及农作物生长状况灵活地采取相应的措施。中央官僚机构无论组织得多么合理,配备多么称职的人员,在灵活有效地组织农事活动方面,远远不及“个体农户”。但是,搞个体农业对“中央官僚机构”的前途不利。苏共政治局不会注意不到“社会主义”与“国家食品长期不足”之间这种令人难堪的联系。但在苏共政治局看来,哪怕是进口更多的粮食,坚持“社会主义的(即集体化的)农业”仍比放弃对农民这一社会阶层的控制更安全、稳妥。

By the same token, it is also difficult for the USSR to amend its industrial sector. To some observers, that may hardly seem necessary, given the remarkable achievements of the Soviet economy since 1945 and the fact that it outproduces the United States in, for example, machine tools, steel, cement, fertilizers, oil, and so on. 133 Yet there are many signs that Soviet industry, too, is stagnating and that the period of relatively easy expansion—caused by fixing ambitious output targets, and then devoting masses of finance and manpower to meeting those figures—is coming to a close. Part of this is due to increasing labor and energy shortages, which are discussed separately below. Equally important, however, are the repeated signs that manufacturing suffers from an excess of bureaucratic planning, from being too concentrated upon heavy industry, and from being unable to respond either to consumer choice or to the need to alter products to meet new demands or markets. Producing masses of cement is not necessarily a good thing, if the excessive investment in it has taken resources from a more needy sector; if the actual cementproduction process has been very wasteful of energy; if the final product has to be transported long distances across the country, thus placing further strains upon the overworked railway system; and if the cement itself has to be distributed among the thousands of building projects which Soviet planners authorized but have never been able to complete. 134 The same remarks might be made about the enormous Soviet steel industry, much of the output of which seems to be wasted—causing some scholars to marvel at the “paradox of industrial plenty in the midst of consumer poverty. ”135 There are, to be sure, efficient sectors in Soviet industry (usually related to defense, which can command large resources and must compete with the West), but the overall system suffers from concentrating upon production without much concern for market prices and consumer demand. Since Soviet factories cannot go out of business, as in the West, they also lack the ultimate stimulus to produce efficiently. However many tinkerings there are to assist industrial growth at a faster rate, it is difficult to believe that they will produce a sustained breakthrough if the existing system of a “planned economy” remains.

同样,苏联若进行工业改革,也将困难重重。由于苏联工业在1945年后取得了举世瞩目的成就,许多产品(如机床、钢、水泥、化肥、石油等)的产量已超过美国,一些观察家认为,苏联工业不必进行改革。但是,苏联工业的发展已出现停滞现象。制定雄心勃勃的产量指标,然后再投入大量财力、人力来实现这些指标,便可轻而易举地增加产量的时代行将过去;其部分原因是,苏联的劳动力和能源日益匮乏(这一问题我们将在以后讨论)。另一同样重要的原因则是官僚主义的计划不切实际,过于重视重工业,不根据消费者的喜好和市场需要调整产品结构。如果水泥工业占用了其他部门迫切需要的资金,如果水泥生产耗能过多,如果其最终产品须长途运输而给负担过重的铁路系统又增加了负担,如果把水泥运到数以千计的根据计划者的指令开工但又永不竣工的建设工程工地,那么,生产大量水泥并不一定是件好事。苏联庞大的钢铁工业处于同样的状况。大量钢材被浪费,出现了“钢铁产量很高却又供不应求”的奇怪现象,使一些学者惊讶万分。毋庸置疑,苏联也有一些效率高的工业部门(这些部门均同国防有关,因为需同西方竞争,可使用大量资源),但苏联的多数工业部门因只重视产量,不关心市场价格和消费者需要而受阻。苏联工厂因不像西方工厂那样搞不好就会破产,因而缺乏提高生产效率的动力。如果继续坚持计划经济体制,无论采取多少提高工业增长率的措施,苏联工业也难以迅速发展。

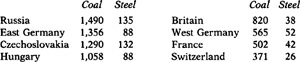

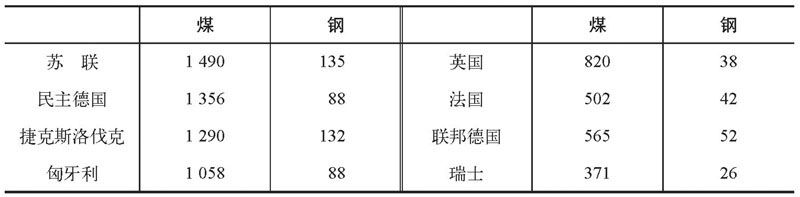

Yet if today’s levels of Soviet industrial efficiency are scarcely tolerable (or, judging from the harsher tone of the government, increasingly intolerable), the system is likely to be even more damaged by three further pressures bearing down upon it. The first of these concerns energy supplies. It has become increasingly obvious that the great expansion in Soviet industrial output since the 1940s heavily depended upon plentiful supplies of coal, oil and natural gas, almost without regard to cost. In consequence, the “energy waste” and “steel waste” in both the USSR and its chief satellites is extraordinary, compared with western Europe, as shown in Table 46.

如果说苏联工业效率低得令人难以忍受(或者以政府更加严肃的语调来判断这种效率越来越令人难以忍受了),还有3个因素可能使这一效率变得更低。第一个因素涉及能源供应问题。我们已日益清楚地看到,20世纪40年代后苏联工业产量的急剧增长,是靠不计成本地消耗大量煤炭、石油和天然气资源换来的。结果,与西欧各国相比,苏联及其主要卫星国的能源与钢的浪费极大(见表46)。

Table 46. Kilos of Coal Equivalent and Steel Used to Produce $1,000 of GDP in 1979-1980 136

表46 1979~1980年创造1000美元的国内生产总值所消耗的煤和钢

(单位:千克)

In Russia’s case, this misuse of “inputs” may have seemed tolerable when its energy supplies were so plentiful and (relatively) easily accessible; but the awful fact is that this is no longer the case. It may have been that the CIA’s famous 1977 forecast that Soviet oil production would soon peak, and then rapidly decline, was premature; nonetheless, Russian oil output did drop a little in 1984 and 1985, for the first time since the Second World War. 137 More alarming still is the fact that the remaining (and very considerable) stocks of oil—and of natural gas—are to be found at much deeper levels or in regions, like western Siberia, badly affected by permafrost. Over the past decade, as Gorbachev reported in 1985, the cost of extracting an additional ton of Soviet oil had risen by 70 percent and this problem was, if anything, intensifying. 138 Hence, to a large degree, the very extensive commitment by Russia to building up its nuclear-power output as swiftly as possible, thus doubling its share of electricity production (from 10 percent to 20 percent) by 1990. It is too soon to know how far the disaster at the Chernobyl plant will hurt those plans—the four reactors at Chernobyl produced one-seventh of the total Russian nuclear-generated electricity, so that their shutdown implied an increased use of other fuel stocks—but what is obvious is that it will both increase costs (because of additional safety measures) and reduce the pace of the planned development of the industry. 139 Finally, there is the awkward fact that the energy sector already absorbs so much capital—about 30 percent of all industrial investment—and that amount is bound to rise sharply. It seems difficult to believe the recent report that “a simple continuation of recent investment trends in oil, coal and electric power, combined with the targeted investment increase for natural gas, will absorb virtually the entire available increase in capital resources for Soviet industry over the period 1981–5,”140 simply because the implications elsewhere are too severe. Nevertheless, the overall pattern is clear: merely to keep the economy growing at a modest pace, the energy sector will require an increased share of the GNP. 141

对于苏联来说,在它能源供应充足、使用方便时,采取这种滥用能源的做法情有可原,但这种情况已时过境迁、今非昔比了。1977年,美国中央情报局曾进行过一次人所共知的预测,认为苏联的石油产量不久将到达顶点,然后便会迅速减少。这一结论虽然下得过早,但1984年和1985年苏联的石油产量确实有所减少,这在第二次世界大战以来还是第一次。更令人震惊的是,剩余的石油(储量仍很大)不是在很深的地层,就是在像西伯利亚西部那样的终年冻土带。1985年,戈尔巴乔夫曾说,在过去的10年中,苏联每多开采一吨石油,就要增加70%的成本费,这种情况将日益严重。有鉴于此,苏联已投入大量资源,以尽快增加核发电量,准备到1990年将核发电量在发电总量中所占的比重提高1倍,即从占10%提高到占20%。切尔诺贝利核电站事故对这一计划到底会有多大影响,现在下结论还为时过早。切尔诺贝利核电站4台机组的发电量占苏联核发电总量的1/7。它的关闭意味着要增加其他核电站的发电量。显而易见,这肯定会提高成本(因为要采取更多的安全措施),放慢计划中的核工业的发展速度。更为棘手的问题是,苏联对能源工业的投资已占其全部工业投资的30%,这个比例肯定还会急剧增加。一份报告指出:“要保持近来在石油、煤炭、电力生产方面的投资趋势,坚持在天然气方面既定的投资增加指标,就须耗费苏联在1981~1985年在工业方面增加的全部投资。”这似乎令人难以置信,因为这样做将给其他部门造成严重的影响。尽管如此,总的模式是清楚的,即仅仅保持较低的经济增长速度,苏联在国民生产总值中也要增加能源产值的比例。

Equally problematic, from the viewpoint of the Russian leadership, is the challenge posed in the high-technology areas of robotics, supercomputers, lasers, optics, telecommunications, and so on, where the USSR is in danger of increasingly falling behind the West. In the narrower, strictly military sense, there is the threat that “smart” battlefield weapons and advanced detection systems could neutralize Russia’s quantitative advantages in military hardware: thus, supercomputers might be able to decrypt Russian codes, to locate submarines under the ocean’s surface, to handle a fast-moving battle scene, and—last but not least—to protect American nuclear bases (as implied in President Reagan’s “Star Wars” program); while sophisticated radar, laser, and guidance-control technology might allow western aircraft and artillery/rocket forces to locate and destroy enemy planes and tanks with impunity—as Israel regularly does to Syrian (Sovietequipped) weapon-systems. Merely to keep up with these advanced technologies requires ever-larger allocations of scientific and engineering resources to Russia’s defense-related sector. 142

在苏联领导人看来,另一个十分棘手的问题是,如何迎接高科技(人工智能、超级电子计算机、激光器、光学器材、电信器材等)的挑战。在这一方面,苏联面临日益落后于西方的危险。仅从狭隘的军事角度看,苏联面临的威胁就很严重:“超级”武器和先进的探测系统可抵消苏联在军事装备方面的数量优势;超级计算机可破译苏联人的密码,测定水下潜艇的位置,控制瞬息万变的战场,保卫美国的核基地(如里根总统在“星球大战计划”中所说的那样);先进的雷达技术、激光技术、制导技术,可使西方的飞机和火炮(或火箭)部队在自己不受伤亡的情况下,摧毁敌方的飞机和坦克。以色列军队就经常对叙利亚的苏制武器系统这样做。仅仅要在这些先进技术领域赶上西方,苏联就必须为其与国防有关的部门分配更多的科学家和工程技术人员。

In the civilian field, the problem is even greater. Given the limitations which are being reached in such classic “inputs” as labor and capital investment, high technology is rightly perceived as being vital for increasing Russian output. To give but one example, the large-scale use of computers could greatly reduce wastage in the discovery, production, and distribution of energy supplies. But the adoption of this new technology not only implies heavy investments (taken from where?), it also challenges the intensely secretive, bureaucratic, and centralized Soviet system. Computers, word processors, telecommunications, being knowledge-intensive industries, can best be exploited by a society which possesses a technology-trained population that is encouraged to experiment freely and to exchange new ideas and hypotheses in the widest possible way. This works well in California and Japan, but threatens to loosen the Russian state’s monopoly of information. If, even today, senior scientists and scholars in the Soviet Union are forbidden to use copying machines personally (the copying departments are staffed by the KGB), then it is hard to see how the country could move toward the widespread use of word processors, interactive computers, electronic mail, etc. without a substantial loosening of police controls and censorship. 143 As in agriculture, therefore, the regime’s commitment to “modernization” and its willingness to allocate additional resources of money and manpower are vitiated by an economic substructure and a political ideology which are basic obstacles to change.

在民用工业方面,问题更加严重。由于传统的“投入”(如劳动力和资本投资)有限,采用高科技遂成为提高苏联工业产量的关键。例如在能源勘探、生产和分配中大量使用计算机,就可极大地减少浪费。但是,采用这一技术不仅需要投入大量资金(资金来自何处?),还意味着苏联高度保密的官僚集权式制度将受到挑战。计算机、文字处理机、传真机和知识密集型产业,只能在这样的社会才能充分发挥其效益,即它的国民受过良好的技术训练,提倡试验创新,能自由交换信息,可大胆提出假想。高科技在加利福尼亚和日本可起重要作用,但在苏联则会危害国家对信息的垄断。如果苏联的高级科学家和学者也不得单独使用复印机(管理复印机的部门都由克格勃的人员控制),如果不让警察机构放松控制和审查,我们很难想象苏联社会会大量使用文字处理机、计算机网络系统和电子邮件等。因此,苏联的工业像在农业方面一样,由于经济结构和政治思想是改革的主要障碍,苏联政府所做的“现代化”许诺与投入的资金和人力,效果肯定受损。

By comparison, then, the increasing reliance of the Soviet Union upon imported technologies and machinery—whether legally traded goods, or stolen from the West —is a less fundamental if still serious problem. The extent of the industrial and scientific espionage (whether for military or commercial purposes) can obviously not be quantified, but seems to be yet another indication of Russia’s worry that it is falling behind. 144 The more regular trade—importing western technology (and also eastern-European manufactures) in exchange for Russian raw materials—is a traditional way in which the country seeks to “close the gap”; it was done in the 1890–1914 period, and again in the 1920s. In that sense, all that has changed is the more modern nature of the product: oil-drilling machinery, rolled steel, pipe, computers, machine tools, equipment for the chemical/plastics industry, etc. What must be much more worrying to Soviet planners is the accumulating evidence that the imported technology takes longer to set up, and is used much less efficiently than in the West. 145 The second problem is the availability of hard currency for the purchase of such technology. Traditionally, this could be circumvented by importing manufactured goods from fellow Comecon countries (thus involving no loss of hard currency), but the latter’s products have increasingly failed to keep up with those from the West, even if they still have to be accepted to prevent a collapse of their eastern-European economies. 146 And while Russia has normally paid for a large proportion of western imports through the barter or direct sale of surplus oil, its prospects (and those of eastern Europe) may be shrinking because of the uncertainties in oil prices, its own growing energy needs, and the general change in the terms of trade for raw materials as manufacturing processes become more sophisticated. 147 At the same time as Russian earnings from oil and other raw materials (except, presumably, gas) shrink, the payments for a variety of imports remain high—all of which presumably reduces the sums available for investment.

目前,苏联对从西方通过合法贸易换来的或非法“偷来”的技术和机器设备的依赖日益严重。相比之下,这虽不十分重要,但也是苏联面临的一个严重问题。苏联进行的工业和科技间谍活动(不论是出于军事目的,还是经济目的)的规模,显然无法确定数量,但它却表明苏联人担心自己落后于西方。通过正当贸易以原料换取西方技术(及东欧产品),是苏联试图缩小“技术差距”的传统方法。在1890~1914年和20世纪20年代,它都这样做过。从这个意义上说,苏联只是进口更加现代化的产品,如石油钻探设备、钢材、输送管、计算机、机床、化学—塑料工业设备等。使苏联计划工作者更为头疼的是,进口技术设备的安装时间不断加长,使用效率也远远低于西方。第二个问题是购买这些技术设备需要的硬通货。过去,苏联可进口经互会兄弟国家的技术设备(可不用硬通货),但这些设备的技术现已日益落后于西方。即使如此,苏联仍不得不购买东欧的产品,以防东欧经济崩溃。苏联一直通过以货易货或直接出售多余石油的方法,来购买大部分西方产品。但是,由于石油价格不稳,本国能源需求量不断增加,生产工艺日益复杂所造成的制成品在换取原材料条件方面的变化,导致苏联(和东欧各国)的外贸前途暗淡。同时,由于石油和其他原材料(天然气可能除外)换取的外汇越来越少,而支付各种进口产品的费用仍然很高,苏联用于投资的款项肯定会减少。

The third major cause for concern about Russia’s future economic growth lies in demographics. The position here is so gloomy that one scholar began his recent survey “Population and Labor Force” with the following blunt statement:

苏联担心影响今后经济增长的第三个因素是人口问题。苏联在这方面的前景如此不佳,以致一位学者在其新著《人口与劳动力》一书中直言不讳地写道:

On any basis, short-term or long-term, the prospects for the development of Soviet population and manpower resources until the end of the century are quite dismal. From the reduction in the country’s birthrate to the incredible increase in the death rates beyond all reasonable past projections; from the decrease in the supply of new entrants to the labor force, compounded by its unequal regional distribution, to the relative ageing of the population, not much hope lies before the Soviet government in these trends. 148

无论是从短期看还是长期看,到20世纪末,苏联人口与劳动力的增长前景都相当暗淡。苏联人口出生率的降低速度和死亡率的急剧上升速度都出乎人们的预料。由于新的劳动力的供应减少,加上劳动力分布不均,人口不断老化,苏联政府在这方面的前景不容乐观。

While all of these elements are serious—and interacting—the most shocking trend has been the steady deterioration in both life expectancy and infant mortality rates since the 1970s and perhaps earlier. Because of a slow erosion in hospital and general health care, poor standards of sanitation and public hygiene, and the fantastic levels of alcoholism, death rates in the Soviet Union have increased, especially among the working males: “Today, the average Soviet man can expect to live for only about 60 years, six years less than in the mid-1960s. ”149 Equally shocking has been the rise in infant mortality—the only industrialized country where this has occurred—to a point where infant deaths are, comparatively, over three times the U. S. rate, despite the enormous numbers of Soviet doctors. Yet if the Russian population is dying off faster than before, its birthrates are slowing down sharply. Because (presumably) of urbanization, higher female participation in the work force, poor housing conditions, and other disincentives, the crude overall birthrate has been steadily dropping, more particularly among the Russian population of the country. The consequences of all these trends is that the male Russian population of the country is scarcely increasing at all.

虽然这些问题都很严重,而且相互影响,但最令人震惊的发展趋势是,20世纪70年代初期(或更早)以后,苏联人的寿命越来越短,婴儿死亡率越来越高。由于医院医疗条件和社会保健条件逐渐恶化,再加上卫生设备不足、公共卫生水平低下和酗酒成风,苏联(特别是男性劳动力)的死亡率一直在上升。“今天,苏联男子的平均寿命仅为60岁,比20世纪60年代中期减少了6岁。”另一个令人吃惊的现象是,苏联的婴儿死亡率不断上升,这在工业化国家中是绝无仅有的。尽管苏联有大量医生,但其婴儿死亡率却是美国的3倍。苏联人的寿命比以前短了,而人口出生率又在急剧下降。由于城市化,参加工作的妇女人数逐渐增多,住房条件差及其他不利因素,苏联的人口出生率一直呈下降趋势,在俄罗斯族中尤为严重。这些趋势所造成的后果是,俄罗斯族男性人口几乎一直没有增加。

The implications of all this have been disturbing Russia’s leaders for some time, and are obviously behind the exhortations to increase family size, the stricter campaign against alcoholism, and the efforts to persuade older workers to remain in the factories. The first is that the country clearly requires a larger proportion of resources to be devoted to health care and social security, especially as the percentage of older population increases: in this the USSR is no different from other industrialized countries (except in its increased death rates), but this again raises the issue of spending priorities. Secondly, there are the implications for both Soviet industry and the armed services, given the drastic fall-off in the rate of growth of the labor force: according to projections, between 1980 and 1990 the labor force will enjoy a net increase of “only 5,990,000 persons, whereas during the preceding ten years the estimated increase in the labor force was 24,217,000. ”150 To leave the military’s problems until later, this trend reminds us again that a large part of the growth in Russian industrial output in the 1950s to the 1970s was due to an enhanced labor force, rather than increases in efficiency; from now on economic expansion can no longer rely upon a fast-increasing work force in manufacturing.

苏联领导人对这些情况造成的后果长期以来一直忧心忡忡,因而鼓励生育,反对酗酒,动员年迈的工人继续留厂工作。首先,随着老年人比例的增加,苏联显然必须把大量财力、物力用于社会保险和医疗卫生。在这一方面,苏联同西方工业化国家别无二致(只是苏联人口死亡率高),但这样又会使苏联领导人考虑将资金首先用于哪些方面的问题。其次,劳动力增长率急剧降低将严重影响苏联的工业和武装部队。据估计,在1980~1990年,苏联劳动力的净增人数只有599万人,而前10年则为2421.7万人。暂不谈对军队的影响,我们不妨回顾一下20世纪50年代到70年代苏联工业产量的增长。在这一时期,苏联工业产量的增长在很大程度上依赖于劳动力数量的增加,而不是效率的提高。从此以后,苏联再也不能靠在制造业中迅速增加劳动力来实现经济增长了。

To a considerable extent, of course, this difficulty could be overcome if more ablebodied males were released from agriculture; but the problem there is that an excessive number of youths in the Slavic areas have already left the communes for the city, whereas the surplus which does exist in the non-Slavic republics is more poorly educated, often has little knowledge of the Russian language, and would require an immense investment in training for industry. This brings us to the final trend which makes Moscow planners uneasy: that since the fertility rates in central Asian republics like Uzbekistan are three times larger than among the Slavic and Baltic peoples, a major shift in the long-term population balances is under way. In consequence, the Russian population’s share is expected to decline from 52 percent in 1980 to only 48 percent by 2000. 151 For the first time in the history of the USSR, Russians will not be in the majority.

当然,如果更多的从事农业生产的男性劳动力进入城市,可在相当程度上克服这些困难。但现在的问题是,斯拉夫族地区离开农村进入城市的青年已经过多;而非斯拉夫族的各加盟共和国虽有剩余劳力,但这些人所受到的教育太少,不懂俄语,进入工厂前需要用大量资金进行培训。这种情况使我们想到了另一个使莫斯科非常不安的发展趋势:中亚各加盟共和国(如乌兹别克斯坦)的人口出生率是斯拉夫人和波罗的海沿岸居民的3倍,因此苏联人口的民族构成从长远看,将发生重大的变化。到2000年,俄罗斯族人在全苏人口中所占的比例,将从1980年的52%,降至48%。在苏联历史上,俄罗斯族人口将首次不再居于多数地位。

This catalog of difficulties may seem too gloomy to certain commentators. Military-related production in the USSR is often impressive and is constantly driven to improve itself because of the dynamic of the arms-race itself. 152 As one historian (admittedly writing in 1981)153 points out, the picture cannot be seen as altogether negative, especially if one looks at Soviet economic achievements over the past halfcentury; and it has been a habit among western observers to exaggerate Russia’s strengths in one period and its weaknesses in the next. Nevertheless, however much the USSR has improved itself since Lenin’s time, the awkward facts are that it has not caught up with the West and, indeed, that the gap in real standards of living seems to have been widening since the later years of the Brezhnev regime; that it is being overtaken, by all measures of per capita output and industrial efficiency, by Japan and certain other Asian countries; and that its slowdown in rate of growth, its aging population, and its difficulties with climate, energy stocks, and agriculture cast a dark shadow over the claims and exhortations of the Soviet leadership.

一些人可能会说,这一大串困难被夸大了。与军事有关的苏制产品常常给人留下深刻的印象,且这些产品因军备竞赛的推动而不断得到改进。1981年,一位历史学家指出:如果回顾一下苏联在50年内所取得的经济成就,人们就会发现,苏联的情况并非一团漆黑。这位历史学家还说,西方观察家有个习惯,时而夸大苏联的强项,时而夸大苏联的弱点。尽管如此,无论苏联自列宁时代以来取得了多么巨大的成就,事实是:苏联始终未赶上西方,实际生活水平与西方的差距自勃列日涅夫执政后期以来一直在加大,在人均产值和工业效率方面,被日本等亚洲国家超过,经济增长率低,人口老化及气候、能源和农业方面的困难,给苏联领导人实现自己目标的前景蒙上了一层阴影。

It is in this context, then, that Gorbachev’s belief that “acceleration of the country’s socioeconomic development is the key to all our problems” becomes the more understandable. And yet, quite apart from natural difficulties (permafrost, etc. ), two main political obstacles stand in the way of producing a “leap forward” on the Chinese model. The first is the entrenched position of the party officials, bureaucrats, and other members of the elite, who enjoy a large array of privileges (depending upon rank) which cushion them from the hardships of everyday life in the Soviet Union, and who monopolize power and influence. To decentralize the planning and pricing system, to free the peasants from communal controls, to allow managers of factories a greater freedom of action, to offer incentives for individual enterprise rather than party loyalty, to close outdated plants, to refuse to accept shoddy products, and to allow a far freer circulation of information would be seen by those in power as dire threats to their own position. Exhortations, more flexible planning, enhanced investments in this or that sector, and disciplinary drives against alcoholism or corrupt management are one thing; but all proposed changes, Soviet party officials have stressed, have to take place “within the framework of scientific socialism” and without “any shifts toward a market economy or private enterprise. ”154 In the opinion of one recent visitor, “the Soviet Union needs its inefficiencies to remain Soviet”;155 if that is so, all Mr. Gorbachev’s urgings about the need for a “profound transformation” of the system are unlikely to make much impact upon the long-term growth rates.

有鉴于此,戈尔巴乔夫所说的“加快社会经济发展是解决我们所有问题的关键”,就不难理解了。但是,苏联即使没有自然条件方面的不利因素(如纬度高),要像中国那样改革,还必须克服两个巨大的政治障碍。第一个障碍是党务官员、政府官员和领导阶层以及其他精英成员根深蒂固的特权地位。这些人权势大,依据职位高低享受各种特殊待遇,不必经受苏联普通人在日常生活中经受的艰辛。采用分散制订计划和决定商品价格的体制、解除集体农庄对农民的控制、给工厂经理以更大的自主权、奖励能干事业而不是只对党忠诚的人、关闭过时的工厂、拒绝接受次品、允许自由交流信息,所有这些都会被掌权者视为对自己地位的严重威胁。苏共领导一方面要求加强教育、更为灵活地制订计划、在各行各业增加投资、加强纪律、反对酗酒、反对腐化,另一方面又强调说,一切改革都必须依据“科学社会主义理论”进行,决不能“搞任何市场经济和私人企业”。一位访问过苏联的人说,“苏联维持苏维埃制度需要低效率”。如果真的如此,戈尔巴乔夫先生关于苏维埃制度需要“深刻改革”的急切呼吁,就不会对苏联的经济增长率产生长期影响。

The second political obstacle lies in the very significant share of GNP devoted by the USSR to defense. How best to calculate the totals and how that measures with western defense spending has exercised many analysts; the CIA’s 1975 announcement that the ruble prices of Soviet weaponry were twice as high as previously estimated—and that Russia was probably spending 11–13 percent of GNP upon defense rather than 6–8 percent—led to all sorts of misinterpretations of what that meant. 156 But the exact figures (which may not even be available to Soviet planners) are less significant than the fact that although the growth in armaments spending slowed down after 1976, the Kremlin appears to have allocated around twice as much of the country’s product to this area as has the USA, even under Reagan’s arms buildup; and this in turn means that the Soviet armed forces have siphoned off vast Stocks of trained manpower, scientists, machinery, and capital investment which could have been devoted to the civilian economy. This does not mean, according to certain economic forecasts, that a large reduction in defense expenditures would quickly lead to a great surge in Russia’s growth rates, simply because of the fact that it would take a long time before, say, a T-72 tank-assembly factory could be retooled to do something else. 157 On the other hand, if the arms race with NATO over the rest of this century drove up the share of Russian defense spending from 14 to 17 percent or more of GNP by the year 2000, a larger and larger amount of equipment such as machine-building and metalworking tools would be consumed by the military, crowding out the share of investment capital going to the rest of industry. Yet, while economists believe that “this will represent a tremendous problem for Soviet decision-makers,”158 all the indications are that defense expenditures will rise faster than GNP growth—and have the consequent effect upon prosperity and consumption.

第二个政治障碍是,苏联国防开支在国民生产总值中占的比例太大。用什么方法能准确地计算出苏联军费开支总额并折合成西方的防务开支,一直是许多西方分析家感到非常棘手的问题。美国中央情报局1975年曾宣布,苏联武器的价格按卢布计算是原先估计的两倍,因而苏联的国防开支不是占苏联国民生产总值的6%~8%,而是11%~13%。这导致了对苏联军费的各种错误的解释。然而,确切的数字(苏联的计划工作者可能也不知道具体的数字)不如下面的事实更有意义:虽然1976年后苏联军费开支的增长率在逐步下降,但克里姆林宫用于国防的费用在国民生产总值中所占的比例仍是美国的两倍,甚至在里根重整军备时期仍然如此。这就是说,苏联武装力量占用了苏联本来可用于发展民用经济的大量训练有素的工人、科学家、机器设备和资金。这也不会像一些人所预言的那样,只要苏联削减国防开支,其经济增长率就会像脱缰之马,奔腾向前。原因很简单,实现经济起飞需要很长时间。例如,一座T-72型坦克装配厂需要改建相当长的时间才能生产其他产品。另一方面,如果到2000年因与北约进行军备竞赛而导致苏联军费在国民生产总值中所占的比例由14%增至17%,苏联军方使用的设备(如机器制造和金属加工设备)将越来越多,对其他的工业部门的投资将越来越少。经济学家们认为,这是苏联决策者面临的一大难题。但是,有迹象表明,今后苏联军费开支的增长率将高于国民生产总值的增长率,这将给苏联的经济繁荣和人民消费水平的提高造成不利影响。

Like every other one of the large Powers, therefore, the USSR has to make a choice in its allocations of national resources between (1) the requirements of the military—in this case, with their built-in ability to articulate Russia’s security needs; and (2) the increasing desire of the Russian populace for consumer goods and better living and working conditions, not to mention improved social services to check the high death and sickness rates; and (3) the needs of both agriculture and industry for fresh capital investment, in order to modernize the economy, increase output, keep abreast of the advances of others, and in the longer term satisfy both the defense and the social requirements of the country. 159 As elsewhere, this involves difficult choices by the decision-makers concerned; yet one has the sense that however large and pressing are the needs both of the Russian consumer and of “modernizing” the economy, the traditional obsession by Moscow with military security means that the fundamental choice has already been made. Unless the Gorbachev regime really manages to transform things, guns will always come before butter and, if need be, before economic growth as well. This, as much as any other characteristic, makes Russia basically different from Japan and western Europe, and even from China and the United States.

因此,苏联如同历史上的所有大国一样,在分配国家资源时,不得不在下述方面进行选择:(1)满足军事方面的要求,即满足苏联的安全需要;(2)满足苏联公众对更多的消费品、更高的生活水平、更好的工作条件的日益强烈的要求,改善社会服务,降低死亡率和患病率;(3)增加对农业、工业的投资,使苏联经济实现现代化,增加产量,赶上发达国家。在较长的时间内满足国防和社会需要,对苏联的决策者来说,是一个困难的抉择。人们的印象是:尽管人民增加消费的要求非常强烈,苏联的经济现代化改造也十分迫切,莫斯科却无法摆脱传统的军事安全观念的束缚,因此,已经做出基本抉择。除非戈尔巴乔夫政权确实决心进行改革,否则大炮总比黄油重要,(如果需要)也比发展经济重要。这些再加上其他因素,使得苏联完全不同于日本、西欧,甚至不同于中国和美国。

Historically, then, the Kremlin today follows the tradition of the Romanov czars, and of Stalin himself, in its desire to have armed forces equal to (and, if preferable, larger than) those of any other Power. There is no doubt that at the present time, the military strength of the USSR is extremely imposing. To try to offer a realistic figure for annual totals of current Soviet defense expenditures would probably be a deception: on the one hand, Moscow’s official figures are absurdly low, concealing large amounts of defense-related spending under other headings (“science,” the space programs, internal security, civil defense, and construction); on the other hand, western estimates of the real total are complicated by the artificial dollarruble exchange rate, limited understanding of Soviet budgetary procedures, the difficulties in, say, the CIA’s effort to put a “dollar cost” on a Russian-made weapon or manpower costs, and institutional/ideological biases. The result is an array of “guestimates,” which one can choose according to one’s fancy. 160 What is not in question, however, is the massive modernization which has occurred in all branches of the Soviet armed forces, both nuclear and conventional, on land and sea and in the air. Whether one considers the rapid growth of Russian land- and sea-based strategic missile systems, the thousands of aircraft and tens of thousands of main battle tanks, the extraordinary developments in the surface navy and in the submarine fleet, the specialist activities (airborne and amphibious warfare units, chemical warfare, intelligence and “disinformation” activities), the end result is impressive. It may or may not have cost as much in real terms as the Pentagon’s own allocations; but it undoubtedly gives the USSR a range of military capabilities which only the rival American superpower possesses. This is not a twentieth-century military Potemkin village, ready to collapse at the first serious testing. 161

从历史的观点看,克里姆林宫继承了罗曼诺夫王朝和斯大林的衣钵,要求有一支可与任何大国军队相匹敌(或更庞大)的武装部队。毫无疑问,苏联当前的军事力量极其强大。要想提供准确的苏联年军费开支总额,看来是不现实的。这是因为,一方面莫斯科官方公布的数字低得使人无法相信,用其他项目(如“科学”、太空计划、公安、民防、建筑等)掩盖了大量与国防有关的开支;另一方面,由于美元与卢布汇率经常人为地变动,对苏联预算程序了解有限,因此将苏制武器和苏联劳务费换算成美元相当困难(如美国中央情报局所做的)。由于对苏联政治制度和意识形态的偏见,西方对苏联国防开支的“猜算”,可谓五花八门,人们完全可以各取所需。然而,无可争辩的事实是,苏联武装部队中的各军兵种、核部队和常规部队(在陆地、在海上、在空中)都在进行大规模现代化改装。人们只要看看苏联迅速增加的陆基和海基战略导弹系统、数千架飞机和数万辆主战坦克、飞速发展的水面舰艇部队和潜艇部队、专业兵种(空降兵、两栖作战部队、化学战部队、情报与反情报部队)的作战能力迅速加强,一切就都明白了。苏联取得这些成就所花的费用也许不像五角大楼那样多,但毫无疑问,苏联获得了只有美国才可与之匹敌的军事力量。这不是20世纪的军事波将金村,在第一次严重考验中就崩溃。

On the other hand, the Soviet war machine also has its own weaknesses and problems, and certainly ought not to be presented as an omnipotent force, able to execute with consummate efficiency all of the possible military operations which the Kremlin might require of it. Since the dilemmas which face the strategy-makers of the other large Powers of the globe are also being pointed out in this chapter, it is only proper to draw attention to the great variety of difficulties confronting Russia’s military-political leadership—without, however, jumping to the opposite conclusion that the Soviet Union is therefore unlikely to “survive” for very long. 162

不过,苏联的军事机器也有弱点和问题。苏军并不是一支能征善战、能高效率地完成克里姆林宫所赋予的任何任务的军队。本章已经说明了其他大国战略家们所面临的困难。因此,我们现在应对苏联军事和政治领导人所面临的各种困难予以注意,但也不能因此认为,苏联的“寿命”不会太长。

Some of the difficulties facing Russian military decision-makers over the middle to longer term derive directly from the economic and demographic problems of the Soviet state which have been outlined above. The first is in technology. Since Peter the Great’s time—to repeat a point made in the previous chapters of this book— Russia has always enjoyed its greatest military advantage vis-à-vis the West when the pace of weapons technology has slowed down enough to allow a standardization of equipment and thus of fighting units and tactics—whether that be the eighteenthcentury infantry column or the mid-twentieth-century armored division. Whenever an upward spiral in weapons technology has placed an emphasis upon quality rather than quantity, however, the Russian advantage has diminished. And while it is clearly true that Russia has substantially closed the technological gap with the West which existed in czarist times, and that its military enjoys unrivaled access to the scientific and productive resources of a state-run economy, there nonetheless is evidence of significant lag times163 in a large number of technological processes. One of the two clearest signs of this is the unease with which the Soviet Union has watched its weaponry being repeatedly outclassed by American hardware in the surrogate battles which have taken place in the Middle East and elsewhere over the past few decades. Admittedly, the quality of North Korean, Egyptian, Syrian, and Libyan pilots and tank crews was never of the highest, but even if it had been, there are grounds to doubt if they could have prevailed against American weapons with far superior avionics, radar equipment, miniaturized guidance systems, and so on. It has probably been in response to this that western experts on the Soviet military report a constant effort to upgrade quality164 and to produce—a few years later —“mirror images” of U. S. weapon systems. But this in turn draws Soviet planners into the same vortex which threatens western defense programs: more sophisticated equipment leads to much longer building times, larger maintenance schedules, heavier (usually) and vastly more expensive (always) hardware, and a decline in production numbers. This is not a comforting trend for a Power which has traditionally relied upon large numbers of weapons to carry out its various and disparate strategical tasks.

从中期和远期看,苏联军事决策人所面临的困难是经济和人口问题。现在,首先谈谈技术问题。从彼得大帝时代起(再重复一下本书前面几章里提出的一个论点),只要其他大国军事技术的发展速度放慢,使武器装备、部队编制(不管是18世纪的步兵纵队,还是20世纪中期的装甲师)以及作战战术实现标准化,俄国就对西方国家享有最大的军事优势。但是,只要武器技术的发展螺旋式上升,质量的重要性大于数量时,俄国的军事优势就消失了。诚然,苏联现在已在很大程度上弥合了在沙皇时代存在的与西方的技术差距,其军方在利用国营经济的科技与生产力方面享有优先权。尽管如此,在许多技术领域,苏联还远远落后于西方。显而易见,有两种情况使苏联人忧心忡忡。一是近几十年来在中东和其他地区进行的代理人战争中,苏制武器往往显得比美制装备略逊一筹。应当承认,朝鲜、埃及、叙利亚、利比亚的飞行员与坦克手绝不是世界上最优秀的。但即使如此,我们也有充分理由怀疑,他们是否能用苏制武器打败使用在航空电子设备、雷达、微型制导系统等方面享有极大优势的美制武器的敌人。西方的苏联军事问题专家报告说,苏联在提高武器质量方面一直在进行不懈的努力,在几年内就可生产出酷似美国武器系统的装备。这可能是苏联人采取的一种对策。然而,这样做会把苏联人也拖入正威胁着西方防务计划的旋涡:越是尖端的武器,制造的时间就越长,维修保养的时间就越多,装备的重量就越大,造价也就越高,而生产的数量则会减少。这对于一个习惯于依靠大量武器完成各项战略任务的国家来说,不是一个令人鼓舞的趋势。

The second sign of Soviet unease about technological obsolescence relates to the so-called Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) of the Reagan administration. It seems difficult at this stage to believe that it would really make the United States completely invulnerable to nuclear attack (for example, it can do nothing against low-flying “cruise” missiles), but the protection it may give to American missile sites and airbases and the added strain upon the Soviet defense budget of producing many more rockets and warheads to swamp the SDI system with sheer numbers can hardly be welcome to the Kremlin. More worrying still, perhaps, are the implications for high-tech conventional warfare. One commentator has pointed out:

第二个使苏联对技术落后感到不安的情况与里根政府提出的“战略防御计划”有关。在现阶段,我们还难以相信这一计划真会使美国免受敌方的核袭击(例如,该计划对低空飞行的巡航导弹就无能为力),但它却可保护美国的导弹发射场、空军基地,能加重苏联国防开支的负担,使之生产更多的火箭和弹头,以便纯粹以数量来搞垮美国战略导弹防御系统。这对克里姆林宫来说,是很难接受的。不过,更令克里姆林宫不安的,是高技术常规战争带来的问题。一位评论家指出:

A defense that can protect against 99 percent of the Soviet nuclear arsenal may be judged as not good enough, given the destructive potential of the weapons that could survive. … [But if] the United States could achieve a technological superiority that would assure destruction of much of the Soviet Union’s conventionally armed aircraft, tanks, and ships, the Soviet numerical advantage would be less threatening. Technology judged less than ideal for SDI may be perfectly applicable for nonnuclear combat. 165

一个能摧毁99%的苏联来袭核弹头的防御系统并不令人满意,因为剩下的导弹仍具有巨大杀伤力……但是,如果美国能取得技术优势,能保证大量摧毁苏联的飞机、坦克、军舰等常规武器,苏联的数量优势就无足轻重了。在“星球大战”计划中不很理想的技术,可能在非核的战争中大显身手。

This, in turn, compels a much larger Russian investment into the advanced technologies of lasers, optics, supercomputers, guidance systems, and navigation: in other words, as one Russian spokesman has put it, there will be “a whole new arms race at a much higher technological level. ”166 Judging from the 1984 warnings of Marshal Ogarkov, then chief of military staff, about the awful consequences of Russia’s failing to match western technology, the Red Army seems less than confident that it could win that sort of race.

而且,这将迫使苏联人投入更多的资金,研制激光器、光学器材、超级计算机、制导系统和导航系统等先进技术装备。这也正如一位苏联发言人所说的:“将在更高的技术水平上进行一场全新的军备竞赛。”前苏军总参谋长奥加尔科夫元帅在1984年曾提醒人们注意苏联技术落后于西方可能造成的可怕后果。由此看来,红军对于它能否赢得这场竞赛的胜利信心不足。

At the other end of the spectrum, there lies a potential demographic threat to Russia’s traditional advantage in quantity, that is, in manpower. As noted above, this is the result of two trends: the overall decline in total USSR birthrate, and the rising share of births in the non-Russian regions. If this is leading to difficulties in the allocation of manpower between agriculture and industry, then it is even more of a long-term problem for military recruitment. In round terms, there ought not to be a problem in taking 1. 3 to 1. 5 million recruits each year from the 2. 1 million males available; but an increasing proportion comes from the Asiatic youth of Turkestan, many of whom are not well versed in the Russian language, have a far lower level of mechanical (let alone electronic) competence, and are sometimes strongly influenced by Islam. All of the studies of the ethnic composition of the Soviet armed forces reveal that the officer corps and NCOs are overwhelmingly Slavic—as are the rocket forces, the air force, the navy, and the technical forces. 167 So, too, unsurprisingly, are the Category I (first-class) divisions of the Red Army. By contrast, the Category II and (especially) Category III divisions and most of service and transport units are manned by non-Slavs, which raises an interesting question about the effectiveness of these “follow-on” divisions in a conventional war against NATO, if the Category I divisions required substantial reinforcement. Labeling this bias “racialistic” and (Great Russian) “nationalistic,” as many western commentators do, is less significant in strictly military terms than the fact that a considerable portion of available Soviet manpower is regarded as unreliable and inefficient by the general staff—which is probably a true judgment, given the reports of Muslim fundamentalism throughout southern Russia and the bewilderment of those troops at, say, having to invade Afghanistan.

另一方面,苏联潜在的人口问题可能威胁它一直享有的数量优势,即兵力优势。如上所述,这是由苏联总人口出生率下降和非俄罗斯地区人口出生率上升这两种趋势造成的。如果说这一情况会给苏联工农业劳动力配置造成不良后果的话,从长远看则会给征兵工作造成更大困难。按理说,每年从210万(原文如此——译者注)适龄男性中征召130万~150万新兵没有问题,但来自土耳其斯坦的亚洲青年所占的比例越来越大。这些人中的许多人不精通俄语,操纵机械设备(且不说电子设备)的能力太差,有时还深受伊斯兰教的影响。所有关于苏联军队民族构成的研究报告都认为,军官、士官及火箭部队、空军、海军和技术部队的人员均主要为斯拉夫人,红军的一类师也主要是斯拉夫人,但苏军二类师、三类师和运输勤务部队的人员则主要是非斯拉夫人。这就提出了一个十分有趣的问题:在与北约的常规战争中,如果一类师需要大量增援部队,这些“后续”师的作战效能如何将十分令人怀疑,把这种怀疑是否归于“种族偏见”和“大俄罗斯民族主义”(许多西方评论家也这样认为),从严格的军事角度看并不重要。重要的是,苏军总参谋部认为,苏联很大一部分适龄青年不可靠、智力低。这种判断可能是对的,因为有报告说苏联南部伊斯兰宗教激进主义势力很大,且入侵阿富汗的苏军中少数民族部队表现不佳。

In other words, like the Austro-Hungarian Empire eighty years ago or, for that matter, the Czarist Empire eighty years ago—the Russian leadership faces a “nationality problem”168 undimmed by the ideology of Marxism. To be sure, the control apparatus now is altogether more formidable than that existing prior to 1914, and one ought perhaps to take with a pinch of salt claims that, for example, the Ukraine is a “hotbed” of disaffection. 169 Nevertheless, long memories about how Ukrainians welcomed the German invaders in 1941, reports of discontent in the Baltic provinces, the forcible (and successful) Georgian protests at the 1978 attempt to make Russian the equal-first language in that republic; above all, perhaps, the straddling across the Sino-Soviet border of millions of Kazakhs and Uighers, and the existence of 48 million Muslims north of the unstable borders with Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan: these facts seem to prey upon the minds of the Russian leadership and to add to their insecurities. More specifically, they provoke an increasing concern about where to place the shrinking numbers of the more “reliable” Slavic youth. Should they be directed into the armed forces, to the Category I divisions and other prestige services, even if fewer and fewer of them are available for industry and agriculture, both of which desperately need infusions of trained and loyal recruits? Or should the non-Slavic population form a growing proportion of the Red Army, despite the risks to military efficiency, in order to release Russians and fellow Slavs for civilian purposes?170 Since the Soviet tradition is one of “safety first,” probably the former tendency will prevail; but far from solving the dilemma, that merely reflects a choice between evils.

换句话说,苏联领导人所面临的“民族问题”,并未因灌入马克思主义的意识形态而有所减弱,其处境犹如80年前的奥匈帝国和沙皇俄国。毋庸置疑,现在的控制措施要比1914年前严格得多,人们也可能对一些说法(如乌克兰是不满的“温床”)有保留意见。但是,我们也不会忘记1941年乌克兰人曾热烈欢迎德国入侵者,读过关于波罗的海沿岸各民族不满的报道,听说过1978年格鲁吉亚人为抗议把俄语变为该共和国第一语言而举行的(成功的)暴力示威。或许,我们尤其应注意在中苏边界居住的、持骑墙态度的数百万哈萨克人和维吾尔族人,以及在不安定的苏土(耳其)、苏伊(朗)、苏阿(富汗)边境地区居住的4800万穆斯林。这些使苏联领导人感到惴惴不安,加重了他们的不安全感,使他们越来越为把比较“可靠”但数量不断减少的斯拉夫青年放于何处而操心费力。是应不顾工农业战线斯拉夫青年越来越少(这两条战线都迫切需要增加训练有素、思想忠诚的新成员),仍把他们送入军队,编入一类师或其他名声好的军队,还是应冒军队战斗力下降的风险,提高红军中非斯拉夫人的比例,从而把俄罗斯人及其斯拉夫同伴解脱出来,从事地方建设?苏联由于有“安全第一”的传统,很可能选择前一种做法。但是这远不能使之摆脱困境,因为这只是一种两害取其一的选择。

If the economic components of what Soviet strategists term “the correlation of forces”171 is a cause for concern among the Politburo, those same leaders can hardly draw much encouragement from the more strictly military aspects of the fastchanging global balance of power. However imposing and alarming the Soviet military machine appears to outside observers, it is nonetheless worth measuring those forces against the array of strategical tasks which the Soviet military may be called upon to carry out.

如果苏联战略家们所说的“力量对比”的经济因素颇使苏共政治局担心,那么迅速变化的全球力量对比中的军事形势,也不会使这些苏联领导人感到欣慰。无论苏联的军事机器在外国观察家看来有多么强大,多么令人望而生畏,将苏联军队与其所承担的战略任务做一番对比是会有益的。

In undertaking such an exercise, it is useful to separate a consideration of conventional warfare from that which may involve nuclear weapons. For obvious reasons, the item in the military balances which has attracted most attention and the most concern is the armory of strategic nuclear weapons in the hands of the Great Powers, and especially of the United States and the USSR, both of which possess the capacity to devastate the globe. For the record, it may be worth reproducing the 1986 “count” of their strategic nuclear warheads by the International Institute of Strategic Studies (see Table 47).

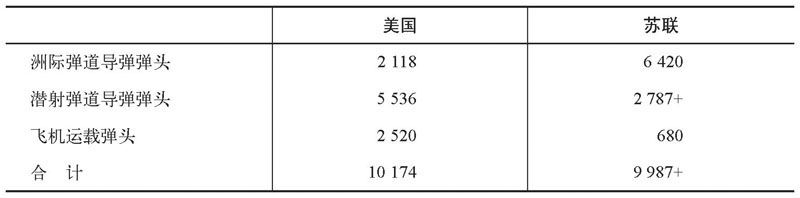

在进行这项工作时,我们应分别考虑常规战争和核战争。由于显而易见的原因,在军事力量对比中人们最关心、最注意的是大国(尤其是美国和苏联)所掌握的战略核武器。美国和苏联都拥有能毁灭人类的核力量。我们不妨先看看伦敦国际战略研究所1986年公布的美苏战略核弹头数(见表47)。

Table 47. Estimated Strategic Nuclear Warheads172

表47 美苏战略核弹头数(估计)

Precisely how one reacts to such figures depends upon one’s interests. To those concerned with numbers alone, or with the possible misrepresentation of numbers, there will be a keen checking of the subtotals and a reminder of the fact that additional large stocks of tactical nuclear weapons are also held by each superpower. 173 To a very considerable number of nonofficial commentators, and to many of the public at large, the sheer extent and destructive capacity of the nuclear weaponry held in these two arsenals is an indication of political incapacity or mental sickness, which threatens all daily life on this planet and should be abolished or greatly reduced as soon as possible. 174 On the other hand, there is that whole cluster of commentators—in think tanks and universities, as well as in defense departments—who have accepted the possibility that nuclear weapons might indeed be used, as part of a national strategy; and who therefore devote their intellectual energies to an intensive study of the respective weapon systems, of escalation strategies and war-gaming, of the pros and cons of arms control and verification agreements, of “throw-weights,” “footprints,” and “equivalent megatonnages,” targeting policies, and “second-strike” scenarios. 175

不同的人对这些数字有不同看法。对于只关心数量、担心数字有诈的人来说,他们将认真检查各类弹头的数量,并提醒人们注意美苏还拥有大量的战术核武器。在许多业余评论家和一般公众来看,美苏建成具有如此规模及杀伤能力的核武库,是一种政治无能或精神失常的表现。它们对这个星球上人类的一切日常生活都造成了威胁,应尽快全部销毁或大量削减。而大学和国防部门的研究者们则认为,核武器作为国家战略的手段之一,确实有可能被使用。因此,他们贡献出自己的全部智慧和精力,深入研究双方的武器系统、升级战略和作战演习、军备控制的利弊与核查协定、“投掷重量”、“百万吨级当量”、“航天器预定着陆地带”、攻击目标方案和“第二次打击”等。

How to deal with “the nuclear problem”176 within a five-century survey such as this obviously presents a major difficulty. Is it not the case that the existence of nuclear weapons—or, rather, the possibility of their mass deployment—has made redundant any consideration of war, of strategy, of economics, from a traditional viewpoint? In the event of an all-out exchange of strategic nuclear weapons, would not estimates of their impact on the “shifting power balances” in world affairs be irrelevant to everyone in the northern hemisphere (and perhaps to everyone in the southern hemisphere as well)? Did not the traditional pattern—of Great Power rivalries turning from time to time into open warfare—finally come to an end in 1945?

显而易见,在涉及500历史年的一本书内阐明“核问题”是相当困难的。由于核武器的存在,尤其是核武器的大规模部署,人们以传统观念来考虑战争、战略和经济问题是否已变得多余?一旦爆发全面核战争,北半球的每个人(可能也包括南半球的每个人)再估计核武器对世界事务中不断变化的力量对比的影响,是否已毫无意义?大国间的竞争不时演变成公开战争的传统模式是否在1945年已经彻底结束?

There is, obviously, no way of answering such questions with certainty. Yet there are indications that today’s Great Powers may be returning to more traditional assumptions about the use of force despite—in many ways, because of—the existence of nuclear weapons. In the first place, there appears to be now—and probably has been for some years—an essential balance in nuclear armaments between the two superpowers. For all the debate about “windows of opportunity” and the possibilities of one side or the other having a “first-strike capability,” it is clear that neither Washington nor Moscow possesses any guarantee that it could obliterate its rival without the likelihood of also suffering devastation; and the coming of a “Star Wars” technology will not significantly alter that fact. In particular, the possession by each side of a great number of submarine-launched ballistic missiles, located in underwater craft which are difficult to detect,177 makes it inconceivable for either side to assume that it could knock out its enemy’s nuclear-weapons capacity all at once. This fact, more than—or at least as much as—fears of a “nuclear winter” will stay the hand of decision-makers, unless they are dragged down by some accidentally induced escalation. It therefore follows that each side is locked into a nuclear stalemate from which it cannot retreat—it being practically impossible either to disinvent nuclear technology or for one (or both) superpowers to give up possession of the weapons—and from which it cannot gain real advantage—since each power’s new system is countered or imitated by the other, and since it is too risky actually to use the weapons themselves.

显然,我们无法对这些问题做出肯定的回答。但是,尽管有核武器存在,仍有迹象表明今日的大国也可能重新采纳运用武力的传统观点。首先,两个超级大国现在处于核均势,或多年来已处于核均势。尽管人们对于是否存在“机会之窗”和任何一方是否具有“首次打击”能力争论不休,但非常清楚的一点是,美国和苏联都不能保证既消灭对手,自己又免遭毁灭,即使部署的“星球大战”系统也不能使这一局面发生重大变化。由于双方都在难以探测的潜艇上部署了大量潜射弹道导弹,美苏都无法确保自己能一举全歼敌方的所有武器。除非出现偶然诱发的核升级,这一情况及对“核冬天”的恐惧足以使决策者不敢轻举妄动。这样,双方就陷入了谁都无法摆脱的核僵局:既不可能消除核技术,超级大国也不可能丢弃所拥有的核武器,而它们又无法取得真正的优势(因为一方对另一方的新武器系统可以仿制或对抗的反措施,而实际使用这些武器又风险太大)。

In other words, the vast nuclear armories of each superpower will continue to exist, but (barring an accidental “triggering”) they are in all likelihood unusable, because they contradict the ancient assumption that in war, as in most other things, there ought to be a balance between means and ends. In a nuclear war, by contrast, the risk is run of inflicting and incurring such damage to mankind that no political, ideological, or economic purpose would be served by it. Although masses of brainpower are devoted to evolving a “nuclear-war-fighting strategy,” it is difficult to contest Jervis’s observation that “a rational strategy for the employment of nuclear weapons is a contradiction in terms. ”178 Once the first missile is unleashed, there would be an end to the “mutual hostage” position into which each side has been locked ever since the United States lost its nuclear monopoly. The results then might be so cataclysmic that no rational political leadership is likely to take the first step across the threshold. Unless there is an inadvertent nuclear war—which is, because of human error or technical malfunction, always possible179—each side is likely to be deterred from “going nuclear. ” If a clash does occur, both the political and the military leaderships will endeavor to “contain” it at the level of conventional fighting.

换言之,两个超级大国的庞大核武器将继续存在,但都无法使用(偶然事故除外),因为使用核武器违反在战争中(在其他大多数事物中也一样)“手段必须与目的相一致”这个自古有之的定理。在核战争中,人类遭受毁灭的危险太大,以致根本无法以战争手段来实现政治、意识形态和经济的目的。虽然许多智囊人物在潜心研究“进行核战争的战略”,但要驳倒杰维斯的观点是困难的。杰维斯认为:“理智地运用核武器的战略语义不通。”一旦发射了第一枚导弹,美国丧失核垄断后双方一直“互为人质”的局面就会结束。由于核战争所造成的灾难极其巨大,任何有理智的政治领导人都不会首先跨越核门槛。除非由于人为的错误或技术故障(这都是可能的)引发核战争,否则美苏双方都不敢动用核武器。如果确实发生了冲突,双方政治、军事领导人会努力把冲突限制在常规范围内。

This does not address what may be a far more serious problem for the two rival superpowers over the next twenty years and beyond: that of nuclear proliferation into countries in the more volatile parts of the world—the Near East, the Indian subcontinent, South Africa, possibly Latin America. 180 Since the states concerned are not part of the Great Power system, the awful possibility of their resorting to nuclear weapons in some regional clash is not considered here: on the whole it seems fair to conclude that the United States and the USSR have a shared interest in halting nuclear proliferation, since it makes global politics more complicated than ever before. If anything, the trend toward proliferation may cause the superpowers to appreciate what they have in common.

今后20年或更长的时间内,两个相互对立的超级大国可能面临更加严重的问题:核武器将扩散到世界上动荡不安的国家和地区(中东、印度次大陆、南非和拉美)。由于这些国家不属于大国之列,本文不讨论它们在地区性冲突中使用核武器的可能性。鉴于核扩散会使全球政治更为复杂,我们有理由认为,在制止核扩散方面,美苏两国之间存在着共同点。核扩散趋势的发展可能使两个超级大国更加重视共同利益。

In a quite different league—from Moscow’s viewpoint, certainly—are the fastexpanding nuclear armories of China, Britain, and France. Until a few years ago, it was commonly assumed that all three of those nations were merely marginal factors in the nuclear balance, and that their nuclear strategy was not at all “credible,” since they could only inflict (in all three cases) limited damage upon the USSR in exchange for their own atomic obliteration. But the indications are that that assumption may soon require modification. The most alarming tendency—again, from Moscow’s viewpoint—is the increasing nuclear capacity of the People’s Republic of China, about which it has been concerned for the past twenty-five years. 181 If the PRC can develop not only a more sophisticated land-based ICBM system but also—as seems its intention—a long-range, submarine-based ballisticmissile system, and if Sino-Soviet disputes are not settled to mutual satisfaction, then the USSR faces the possibility of a future armed clash along the borders which might escalate into a nuclear interchange with its Chinese neighbor. As things are at present, the devastation of the PRC would be immense; but Moscow cannot exclude the possibility that at least a certain number (and, the 1990s, a larger number) of Chinese nuclear missiles would hit the Soviet Union.

对迅速发展的中国、英国和法国的核力量,苏联则另有看法。在几年前,人们一致的看法是,三国的所有核武器在核力量对比中只是无足轻重的因素。由于这三国在核交锋中只能给苏联造成有限的损失,它们的核战略根本没有威慑作用。但情况表明,这种看法也许很快就要予以纠正。在苏联看来,最令人惊恐的事态莫过于中国核力量的增长。对于这一事态,苏联已经焦虑了25年。如果中国不仅能研制出更加先进的陆基洲际弹道导弹系统,还能按其意愿研制出潜射远程弹道导弹系统,如果双方无法圆满地解决中苏争端,那么中苏未来的边界武装冲突就有可能升级为核战争。如果冲突真的升级,就目前情况看,中国会遭到严重破坏,但莫斯科也无法排除一定数量的中国导弹(到20世纪90年代数量会更多)击中苏联的可能性。

More worrying technically, although perhaps less alarming politically, is the buildup of the British and French nuclear delivery and warhead capacities. Until recently, the “deterrent” effect of both of these Powers’ strategic weapon systems appeared dubious. In the rather implausible event of their being involved in a nuclear interchange with the USSR, and with the United States neutral (which is, after all, the justification for the British and French systems), it was difficult to see them risking national suicide when they could only inflict partial damage upon Russia from their own modest delivery systems. In the next few years, however, the devastation which each of those midsized Powers could do to the USSR will be multiplied many times, because of the vast enhancement of their submarinelaunched ballistic-missile systems. For example, Britain’s acquisition of submarines carrying the Trident II missile system—derided by The Economist as “the Rolls Royce of nuclear missiles”182 because of its high cost and excessive striking power—will give that country a nearly invulnerable deterrent force which could destroy more than 350 Soviet targets, instead of the present sixteen-plus targets. In rather the same way, France’s new submarine L’Inflexible, with the longer-range, multiwarhead M-4 missile, is probably capable of attacking ninety-six Soviet targets—“more than all of France’s five earlier nuclear submarines combined”183—and when the other boats have been reequipped with the same M-4 missile, France’s strategic warheads will have increased fivefold, allowing it also to be theoretically capable of hitting hundreds of Russian targets from thousands of miles away.

英法两国核发射系统的增多和弹头威力的增大在政治上虽不令人吃惊,在技术上却使莫斯科感到不安。直到最近,英法两国战略核武器系统是否能起到“威慑作用”仍令人怀疑。这两个国家用自己的那一点发射系统只能给苏联造成轻微的损失。因此,在美国保持中立的情况下(这恰是两国为自己拥有核武器系统进行辩护的理由),两国不会冒举国自杀的危险与苏联进行核战。但是,由于在今后几年英法的潜射弹道导弹会大量增加,这两个中等强国对苏联的杀伤能力将提高数倍。例如,采购携带“三叉戟-Ⅱ”型导弹系统的潜艇(因其价格昂贵、攻击力强而被《经济学人》杂志称为“核导弹的劳斯莱斯”)后,英国将拥有一支几乎战无不胜的威慑力量,可摧毁的苏联目标将从16个,增加到350余个。同样,法国携带M-4型多弹头远程导弹的“灵敏”号新式潜艇,可摧毁96个苏联目标。这个数字比法国5艘老式核潜艇(法国只有5艘核潜艇)所能摧毁的目标总数还要多。当其他几艘核潜艇也装上M-4型导弹后,法国的战略核弹头将增加5倍,并在理论上获得从数千英里的距离外攻击数百个苏联目标的能力。

What this means in real terms it is, of course, impossible to forecast. In Britain itself many prominent figures have found the idea that their country would independently use its nuclear weapons against Russia to be, literally, “incredible”;184 and such critics are unlikely to be swayed by the counterargument that the country’s own suicide would at least be attended by inflicting much heavier damage upon the USSR than was possible hitherto. In France, too, public opinion—and some strategic commentators—find its declared deterrent policy to be scarcely credible. 185 On the other hand, it seems fair to assume that Russian military planners, who take nuclear-war-fighting possibilities very seriously indeed, must find these recent developments disturbing. Not only will they face four countries—instead of the United States alone—with the potential to inflict heavy (perhaps extraordinarily heavy) damage upon the Soviet heartland, but they must consider what the subsequent world military balances would look like if Russia was involved in a nuclear interchange with one of these Powers (say, China) while the others were neutral observers of such mutually inflicted devastation. Hence the Soviets’ repeated insistence that in any overall Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty with the United States the Anglo-French systems have to be taken into account, and that the USSR must have a certain margin of nuclear force to take care of China. All this, it seems reasonable to suggest, makes nuclear weapons an ever more dubious instrument of rational military policy from the Kremlin’s viewpoint.

当然,英法核力量的增强到底意味着什么是无法预测的。在英国,许多知名人士指出,那种认为英国可以独立地使用核武器抗击苏联的想法实际上是不足取的。持另一种意见的人却反驳说,英国的“自杀”至少能给苏联造成巨大的损失。法国公众和一些战略评论家感到法国政府所宣称的威慑政策作用也不大。但另一方面,人们有理由相信,非常认真地对待核战争可能性的苏联军事计划人员,肯定会对最近的事态发展感到头疼。他们不仅面临4个可给苏联心脏地区造成巨大破坏的国家(已不仅是美国一国),而且还必须考虑,如果苏联与4国中的一国(如中国)进行核交战,其余三国保持中立,坐视它们相互残杀,战后的世界军事力量对比会有何变化。正因为如此,苏联人才反复强调说,苏联在与美国签订《全面限制战略武器条约》时,不仅要考虑英法两国的核系统,还要考虑留出一定的力量对付中国。在克里姆林宫看来,所有这些情况已使核武器变为在执行合理的军事打击政策时无法使用的手段。

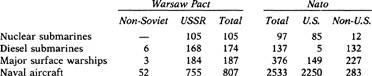

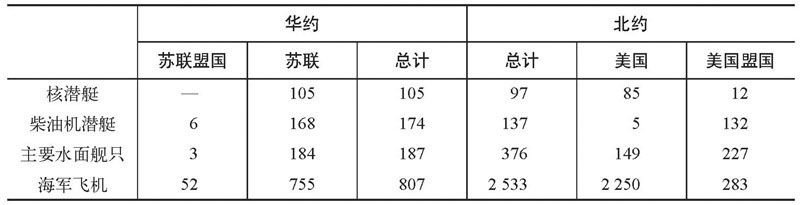

If, however, this leaves conventional weapons as the chief measure of Soviet military power—and the chief tool for securing the political aims of the Soviet state —it is difficult to believe that Russian planners can feel much more assured at the present state of the international military balance. This may seem a bold statement to make in view of the very extensive publicity which has been given to the far larger totals of Soviet aircraft, tanks, artillery, and infantry divisions in assessments of the U. S. -USSR “military balance”—not to mention the frequent assertion that NATO forces, unable to hold their own in a large-scale conventional war in Europe, would be compelled to “go nuclear” within a matter of days. Yet an increasing number of the most recent academic studies of the “balance” are now suggesting that that is precisely what exists—namely, a situation in which “there still appears to be insufficient overall strength on either side to guarantee victory. ”186 To reach this conclusion involves both very detailed comparative analyses (e. g. , of the composition of the U. S. as opposed to Russian tank divisions) and considerations of certain larger and intangible factors (e. g. , the role of China, the reliability of the Warsaw Pact), and only a summary of these arguments can be provided here. If, however, this evidence is even roughly correct, it also cannot be very comforting to Soviet planners.

即使常规武器是衡量苏联军事力量的主要标准,是苏联实现其政治目标的主要手段,我们也很难相信苏联人对目前国际军事力量对比会感到心中有数。这似乎是一个非常大胆的看法,因为人们经常听到的是,在美苏“军事力量对比”中,苏联的飞机、坦克、火炮、步兵师的总数远远多于美国。人们还经常宣称,北约部队在欧洲大规模常规战争中,将无力坚守阵地,在几天后就不得不使用核武器。但是,近来越来越多的学术研究报告认为,目前的真实情况是“双方的力量都不足以保证自己取得胜利”。这一结论是进行了详尽的比较分析(例如对美国装甲师与苏联坦克师的编成进行比较分析),研究了某些影响更大但难以预测的因素(例如中国的作用、华沙条约的可靠性)后得出的。在此,我们只能加以简要说明。这一结论的根据即使大致属实,也会令苏联的参谋人员极不舒服。

The first and most obvious point to be made is that any analysis of the conventional balance of forces needs to measure the rival alliances as a whole, especially in their European context. As soon as that is done, it becomes evident that the non-American parts of NATO are much more significant than the non-Russian parts of the Warsaw Pact. Indeed, as the 1985 British Defence White Paper made pains to point out, “European countries were providing the major part of the ready [NATO] forces stationed in Europe: 90 percent of the manpower, 85 percent of the tanks, 95 percent of the artillery and 80 percent of the combat aircraft; and over 70 percent of the major warships in Atlantic and European waters. … The full mobilized strength of European forces was nearly 7 million men as against 3. 5 million for the United States. ”187 It is, of course, also true that the United States has deployed 250,000 men in situ in Germany, that the army divisions and air squadrons which it plans to pour across the Atlantic in the event of a European war would be critical reinforcements, and that NATO as a whole depends upon the American nuclear deterrent and upon American sea power. But the point is that the North Atlantic Alliance is much more evenly balanced between, as it were, the twin pillars of the “arch,” than is the Warsaw Pact, which is top-heavy and skewed toward Moscow. It is also worth noting that America’s NATO allies spend six times more on defense than Russia’s Warsaw Pact allies; indeed, Britain, France, and West Germany each spend more than the non-Russian Warsaw Pact countries together. 188

首先要说清楚的一点是,任何关于常规力量的对比分析,都应将两个敌对联盟视为一个整体来衡量,在欧洲尤其如此。只要这样观察问题,我们就会发现,北约不包括美国的部分要比华约不包括俄国的部分重要得多。的确,正像《1985年度英国国防白皮书》所指出的:“驻在欧洲的北约一线部队大部分来自欧洲国家,即欧洲国家提供90%的兵力、85%的坦克、95%的火炮、80%的战斗机以及在大西洋和欧洲海域70%以上的主力舰只……欧洲可动员兵力近700万人,而美国只有350万人。”当然,美国也在德国部署了25万人,一旦欧洲燃起战火就准备跨过大西洋的美国陆军师、空军中队也是必不可少的增援部队,且总的来看北约还要依赖美国的核威慑和美国的海上力量。但重要的是,北约这座大厦的基础较为牢固,不像华约那样头重脚轻、需要靠苏联。还值得注意的一点是,美国北约盟国的防务开支比苏联的华约盟国高6倍;英国、法国和联邦德国每个国家的国防开支,比苏联以外华约各国军费的总和还要多。

If, then, the strength of the two alliances is measured as a whole, and without the curious omissions and provisos which have characterized some of the more alarmist western assessments,* a picture emerges of strategical parity in most respects; and even where the Warsaw Pact has the edge in numbers, that does not look decisive. For example, each alliance appears to have roughly similar “total ground forces in Europe”; they also have similar “total ground forces” and “total ground force reserves. ”189 In the roundest sense of all, the Warsaw Pact’s 13. 9 million men (6. 4 million “main forces” and 7. 5 million reserves) is not vastly greater than NATO’s 11. 9 million men (5 million “main forces” and 6. 8 million reserves), the more especially since a large proportion of the Warsaw Pact total consists of Category III units and reserve forces of the Red Army. Even on the critically important Central Front, where NATO forces are most seriously outnumbered by the masses of Russian armored and motor-rifle divisions, the Warsaw Pact’s advantage is not a very comforting one—especially when it is recalled how difficult it would be to conduct fast, offensive, “maneuver warfare” in the crowded terrain of northern Germany and when it is realized how many of Russia’s 52,000 “main battle tanks” are the obsolescent T-54s—which would simply clog up the roads. Provided NATO has sufficient reserves of ammunition, fuel, replacement weaponry, etc. , it certainly seems to be in a much better position to blunt a Soviet conventional offensive than it was in the 1950s. 190

如果全面衡量两大集团的力量,而不像西方人那样为了使自己的评估结果耸人听闻进行毫无道理的删节,我们就会发现,两个集团在多数方面处于战略均势。华约在某些方面虽有数量优势,但并不举足轻重。例如,双方在欧洲的地面部队数量大体相当,地面部队总数及后备役地面部队总数也大体相同。根据最准确的估计,华约的兵力为1390万人(其中640万为主力部队,750人为预备役),没有大大超过北约1190万人的总兵力(其中500万人为主力部队,680万人为预备役)。况且,华约军队中还有相当一部分是三类师和红军的预备役部队。在极其重要的中欧战场,北约军队与大量的苏联装甲师和摩托步兵师相比,数量上的差距最为严重。但即使如此,如果想想在城镇林立、人口稠密的德国北部实施“快速机动进攻战”是多么困难,看看苏联5.2万辆主战坦克中有那么多是只能堵塞道路的老式T-54型坦克,我们就会感到华约的优势并非很令人不安。只要在弹药、燃料和武器等方面有充足的储备,北约就会比20世纪50年代更容易挫败苏联的常规进攻。

In addition, there is the incalculable element of the integrity and cohesion of the respective military alliances. That NATO has many weaknesses is undeniable: from the frequent transatlantic disputes over “burden sharing” to the tricky issue of intergovernmental consultation in the event of pressure to launch nuclear missiles. Neutralist and anti-NATO sentiment, detectable in left-of-center parties from West Germany and Britain to Spain and Greece, is also a cause of periodic concern. 191 And if there were to be, at some future time, a “Finlandization” of any of the states lying along the Warsaw Pact’s western boundary (especially, of course, West Germany itself), then that would be a massive strategical gain to the USSR as well as providing economic relief. Yet even if such a scenario is possible in theory, that can hardly compare with the worries which Moscow must presently entertain about the reliability of its “empire” in eastern Europe. The broad-based popularity of the Solidarity movement in Poland, the evident East German wishes to improve relations with Bonn, the “creeping capitalism” of the Hungarians, the economic woes which are affecting not merely Poland and Rumania but all of eastern Europe, pose extraordinarily difficult problems for the Soviet leadership. They are not issues which can be readily solved by the use of the Red Army; nor, however, does it appear that fresh doses of “scientific socialism” would provide an answer satisfactory to the eastern Europeans. Despite the Kremlin’s recent rhetoric about the modernization and reexamination of Marxist economic and social policies, it is difficult to see Russia relinquishing its many controls over eastern Europe. Yet these varied signs of political discontent and economic distress must call ever more into question the reliability of the non-Russian armies in the Warsaw Pact. 192 The Polish armed forces, for example, can hardly be reckoned as an addition to the pact’s strength; if anything, the reverse is true, since they—and the critically important Polish road and rail lines—would need close Red Army supervision in wartime. 193 Similarly, it is difficult to imagine the Czech and Hungarian armies enthusiastically rushing forward to assault NATO positions upon Moscow’s orders. Even the attitudes of East German forces, probably the most effective and modernized of Russia’s allies, may be affected by the order to attack westward. It is true that the great bulk (four-fifths) of the Warsaw Pact’s forces are Russians, and that Soviet divisions would be the real spearhead in any conventional war with the West; but it will be a considerable task for Red Army commanders both to conduct such a war and to keep an eye upon the million or more eastern European soldiers, most of them not very efficient and some of them not very reliable. 194 The possibility (however remote) that NATO may even seek to respond to a Warsaw Pact offensive by mounting its own counteroffensive, into, say, Czechoslovakia,195 can only increase an unease which is probably as much political as it is military.

此外,在比较两大军事集团时,还要考虑团结、凝聚力等无法用数量表达的因素。北约的弱点是不容否认的。大西洋两岸经常为“军费负担”问题争论不休;出现危机时,各国政府为发射核导弹而必须进行反复协商也是个棘手的问题。联邦德国、英国、西班牙、希腊等国的“中左”政党内,有许多人主张中立并有反北约情绪,这些都不时引起焦虑。如果有朝一日,某个与华约西部边界接壤的国家(特别是联邦德国)实行“芬兰化”,这不仅可使苏联在战略上得到重大利益,还可减轻苏联的经济负担。但是,即使这种情况的发生在理论上是可能的,它也无法与苏联对东欧各国可靠性的担心相比。具有广泛群众基础的波兰团结工会运动,民主德国希望与波恩改善关系的迹象,“蹑手蹑脚地走向资本主义”的匈牙利,波及波兰、罗马尼亚以及整个东欧的经济困难,都是苏联领导人必须正视而又很难解决的问题。这些问题不是动用苏联红军就能解决的,对“科学社会主义”的新解释看来也不能使东欧人满意。尽管苏联领导人最近发表了一些关于现代化和对马克思主义经济政策进行重新审视的言论,但是人们还难以看到苏联要取消对东欧的控制。然而,这种种政治不满和经济困难的情况必然使人们更加怀疑华约非苏联军队的可靠性。例如,人们几乎都认为,波兰军队不会增强华约的力量,因为在战时苏联红军须对波兰军队及波兰境内至关重要的公路和铁路进行了严密的监视。同样,人们也难以想象,捷克斯洛伐克军队和匈牙利军队会按照莫斯科的命令,去积极主动地进攻北约阵地。甚至苏联盟军中战斗力最强、最现代化的民主德国军队的态度,在得到向西进攻的命令时也可能发生变化。的确,华约军队中大部分是苏联人(占4/5),苏军师在与西方的常规战争中将是真正的先头突击部队。不过,如果苏联红军指挥官在进行这样一场战争的同时,又要监视100多万战斗力不强而又不太可靠的东欧士兵,这任务可能不会轻松。北约以反攻(譬如攻入捷克斯洛伐克)来回敬华约进攻的可能性无论多么小,也能使苏联的政治和军事领导人更加心神不安。