The United States: The Problem of Number One in Relative Decline

相对衰落的美国

It is worth bearing in mind the Soviet Union’s difficulties when one turns to analyze the present and the future circumstances of the United States, because of two important distinctions. The first is that while it can be argued that the American share of world power has been declining relatively faster than Russia’s over the past few decades, its problems are probably nowhere near as great as those of its Soviet rival. Moreover, its absolute strength (especially in industrial and technological fields) is still much larger than that of the USSR. The second is that the very unstructured, laissez-faire nature of American society (while not without its weaknesses) probably gives it a better chance of readjusting to changing circumstances than a rigid and dirigiste power would have. But that in turn depends upon the existence of a national leadership which can understand the larger processes at work in the world today, and is aware of both the strong and the weak points of the U. S. position as it seeks to adjust to the changing global environment.

当你致力于分析美国的现实境况并探索它的未来时,由于两个重要的区别,有必要牢记苏联所面临的困难。这两个区别是:第一,尽管有人会说,在已往的几十年里,美国作为一个世界大国比苏联衰落得相对快些,但它的问题远不如它的对手苏联严重。况且,美国的绝对实力(特别是在工业和技术领域)远比苏联雄厚。第二,同一个僵化且控制甚严的大国相比,美国社会那种结构松散和自由放任的特性(尽管不无缺点),有可能在适应变化的环境方面赋予它更好的机会。但是,反过来,这又要求美国领导人能理解当今世界正在进行的更大的变动进程,要求他们在适应全球环境变化的过程中意识到美国自身的优势和弱点。

Although the United States is at present still in a class of its own economically and perhaps even militarily, it cannot avoid confronting the two great tests which challenge the longevity of every major power that occupies the “number one” position in world affairs: whether, in the military/strategical realm, it can preserve a reasonable balance between the nation’s perceived defense requirements and the means it possesses to maintain those commitments; and whether, as an intimately related point, it can preserve the technological and economic bases of its power from relative erosion in the face of the ever-shifting patterns of global production. This test of American abilities will be the greater because it, like Imperial Spain around 1600 or the British Empire around 1900, is the inheritor of a vast array of strategical commitments which had been made decades earlier, when the nation’s political, economic, and military capacity to influence world affairs seemed so much more assured. In consequence, the United States now runs the risk, so familiar to historians of the rise and fall of previous Great Powers, of what might roughly be called “imperial overstretch”: that is to say, decision-makers in Washington must face the awkward and enduring fact that the sum total of the United States’ global interests and obligations is nowadays far larger than the country’s power to defend them all simultaneously.

尽管就目前来讲美国在经济上甚至军事上仍是天下无双,但它迟早逃脱不了两种重大考验,这两种考验对任何在世界事务中占据“第一”的大国的寿命都曾构成严峻挑战。这两种考验是:在军事或战略领域,该大国能否在其预期的国防需求和它所拥有的履行所承担义务的手段之间,保持适度的平衡;同这一点密切相关的是,面对不断变化的全球生产格局,该大国能否在相对的衰落中保持其实力的科技和经济基础。这种对美国能力的挑战将会更加严峻,因为正像1600年前后的西班牙帝国或者1900年前后的大英帝国一样,美国是大量战略义务的继承者,而这些义务都是在几十年前国家影响世界事务的政治、经济和军事能力如此毋庸置疑的时候所承担下来的。结果是,同以往大国的兴衰史十分相像,美国也正面临着“帝国战线过长”的危险,也就是说,华盛顿的决策者不得不正视这样一种棘手而持久的现实,即美国全球利益和它所承担的义务总和,已远远超过它能同时保卫的能力。

Unlike those earlier Powers that grappled with the problem of strategical overextension, the United States also confronts the possibility of nuclear annihilation—a fact which, many people feel, has changed the entire nature of international power politics. If indeed a large-scale nuclear exchange were to occur, then any consideration of the United States’ “prospects” becomes so problematical as to make it pointless—even if it also is the case that the American position (because of its defensive systems, and geographical extent) is probably more favorable than, say, France’s or Japan’s in such a conflict. On the other hand, the history of the post-1945 arms race so far suggests that nuclear weapons, while mutually threatening to East and West, also seem to be mutually unusable—which is the chief reason why the Powers continue to increase expenditures upon their conventional forces. If, however, the possibility exists of the major states someday becoming involved in a nonnuclear war (whether merely regional or on a larger scale), then the similarity of strategical circumstances between the United States today and imperial Spain or Edwardian Britain in their day is clearly much more appropriate. In each case, the declining number-one power faced threats, not so much to the security of its own homeland (in the United States’ case, the prospect of being conquered by an invading army is remote), but to the nation’s interests abroad—interests so widespread that it would be difficult to defend them all at once, and yet almost equally difficult to abandon any of them without running further risks.

同以往被战略上的过度扩展所困扰的大国不同的是,美国还面临着核毁灭的危险。很多人认为,正是这一点完全改变了国际强权政治的性质。如果一场大规模的核战争真的发生,那么有关美国“前途”的任何考虑都将值得怀疑,以至于使这种考虑本身毫无意义;即使美国在这样一场冲突中(因其防御系统和地理优势)处于比法国或日本更有利的地位,情况也完全一样。另一方面,1945年以后军备竞赛的历史已经表明,尽管核武器对东方和西方都构成巨大威胁,但它们对谁都显得难以使用,这正是大国之所以增加常规力量方面的开支的一个主要原因。然而,如果存在大国之间有朝一日卷入一场非核战争(不论是纯地区性的还是较大规模的)的可能性,那么今日美国同昔日的西班牙帝国或爱德华七世时的大英帝国在战略环境上的相似之处,就变得十分明显而且恰如其分。在每一种情况下,衰落中的头号强国都面临着众多威胁,而且这些威胁对其本土安全(就美国来讲,被一支入侵军队征服的前景十分遥远)来说算不了什么,但对国家的海外利益来说却是十分严峻,因为它们的海外利益如此广泛,以致很难同时保卫;并且要想放弃其中任何一种利益而又不冒更大的风险,几乎同样困难。

Each of those interests abroad, it is fair to remark, was undertaken by the United States for what seemed very plausible (often very pressing) reasons at the time, and in most instances the reason for the American presence has not diminished; in certain parts of the globe, U. S. interests may now appear larger to decision-makers in Washington than they were a few decades ago.

应当指出,美国的每一种海外利益都是因它在当时看来似乎很有道理(常常又颇为紧迫)的理由承担起来的,而且在绝大多数情况下,需要美国出面的这些理由尚未消失。对华盛顿的决策者来讲,美国在世界某些地方的利益比几十年前甚至更为重大了。

That, it can be argued, is certainly true of American obligations in the Middle East. Here is a region, from Morocco in the west to Afghanistan in the east, where the United States faces a number of conflicts and problems whose mere listing (as one observer put it) “leaves one breathless. ”208 It is an area which contains so much of the world’s surplus oil supply; which seems so susceptible (at least on the map) to Soviet penetration; toward which a powerfully organized domestic lobby presses for unflinching support for an isolated but militarily efficient Israel; in which Arab states of a generally pro-western inclination (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the Gulf emirates) are under pressure from their own Islamic fundamentalists as well as from external threats such as Libya; and in which all the Arab states, whatever their own rivalries, oppose Israel’s policy toward the Palestinians. This makes the region very important to the United States, but at the same time bewilderingly resistant to any simple policy option. It is, in addition, the region in the world which, at least in some parts of it, seems most frequently to resort to war. Finally, it contains the only territory—Afghanistan—which the Soviet Union is attempting to conquer by means of armed force. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the Middle East has been viewed as requiring constant American attention, whether of a military or a diplomatic kind. Yet the memory of the 1979 debacle in Iran and of the ill-fated Lebanon venture of 1983, the diplomatic complexities of the antagonisms (how to assist Saudi Arabia without alarming Israel), and the unpopularity of the United States among the Arab masses all make it extremely difficult for an American government to conduct a coherent, long-term policy in the Middle East.

就美国在中东所承担的义务而言,这一点非常正确。这是一个西自摩洛哥、东到阿富汗的广阔地带;正是在这里,美国面临着一系列的冲突和难题,仅这些问题本身(正如一位观察家所指出的那样)就足以使人“喘不过气来”,望而却步。中东既控制着世界石油供应量的绝大部分,又很容易受到苏联的渗透;美国国内有一个强大的、有组织的院外集团,在坚定不移地为孤立但在军事上却卓有成效的以色列奔走呼号;这里的那些有亲西方倾向的阿拉伯国家(埃及、沙特阿拉伯、约旦和海湾的阿拉伯联合酋长国)既受到来自内部的伊斯兰宗教激进主义者的压力,又面临来自外部如利比亚之类的威胁;这里的所有阿拉伯国家,不管它们之间如何争斗,都一致反对以色列对巴勒斯坦的政策。所有这些都使该地区对美国至关重要。然而,与此同时,任何简单的政策选择都难以适用于该地区,这又使人手足无措。另外,该地区又是世界上最有可能经常发生战事的地区(至少一些地方是如此)。最后,该地区还有一个苏联试图以武力征服的阿富汗。因此,毫不奇怪,中东一直被美国视为需要持久关注——不论通过外交方式,还是通过军事行动——的重点地区。然而,1979年在伊朗解救人质行动的失败和1983年在黎巴嫩冒险的厄运,仍然记忆犹新,加之该地区矛盾的外交复杂性(如何既支持沙特阿拉伯又不使以色列担惊受怕)和美国在阿拉伯世界的不得人心,都使美国政府要想推行一项连贯的、长期的中东政策非常困难。

In Latin America, too, there are seen to be growing challenges to the United States’ national interests. If a major international debt crisis is to occur anywhere in the world, dealing a heavy blow to the global credit system and especially to U. S. banks, it is likely to begin in this region. As it is, Latin America’s economic problems have not only lowered the credit rating of many eminent American banking houses, but they have also contributed to a substantial decline in U. S. manufacturing exports to that region. Here, as in East Asia, the threat that the advanced, prosperous countries of the world will steadily increase tariffs against imported, low-labor-cost manufactures, and be ever less generous in their overseas-aid programs, is a cause for deep concern. All this is compounded by the fact that, economically and socially, Latin America has been changing remarkably swiftly over the past few decades;209 at the same time, its demographic explosion is pressing ever harder upon the available resources, and upon the older conservative governing structures, in a considerable number of states. This has led to broad-based movements for social and constitutional reforms, or even for outright “revolution”— the latter being influenced by the present radical regimes in Cuba and Nicaragua. In turn, these movements have produced a conservative backlash, with reactionary governments proclaiming the need to eradicate all signs of domestic Communism, and appealing to the United States for help to achieve that goal. These social and political fissures often compel the United States to choose between its desire to enhance democratic rights in Latin America and its wish to defeat Marxism. It also forces Washington to consider whether it can achieve its own purposes by political and economic means alone, or whether it may have to resort to military action (as in the case of Grenada).

在拉丁美洲,也可看到对美国国家利益的日益增长的挑战。如果世界上发生一场大规模的国际债务危机,并给全球的信贷体系,特别是给美国的银行以沉重打击,那么这场危机最有可能从拉美开始。事实上,拉美的经济问题不仅降低了美国许多著名银行对客户信贷分类的等级,而且还导致了美国制品对该地区出口的持续下降。在这里也正如在东亚一样,世界上先进的富裕国家提高对进口的低劳动成本制品的关税,并对海外援助计划表示冷淡。这本身就是一种不小的威胁,足以引起人们的担心。所有这些问题又同拉美地区几十年来在经济上和社会上所发生的巨大变化掺杂在一起;同时,拉美地区的人口爆炸正日益压迫着它所能获得的资源,也对大多数拉美国家陈旧的、保守的统治体系产生了强大压力。这导致了种种基础广泛的社会和宪法改革运动,甚至还有彻底的“革命”运动,而后者又受到了来自古巴和尼加拉瓜激进政权的影响。由于反对革命的政府宣称要铲除国内所有的共产主义苗头,并请求美国帮助实现这一目的,这些运动反而又导致了保守主义的回潮。拉美地区所存在的这些社会和政治裂痕,常常迫使美国在两种愿望之间进行选择:是在拉美各国提携民主权利,还是战胜各国的马克思主义。拉美地区的问题也使得美国在以下两种策略之间进行权衡——能否仅通过政治和经济手段达到自己的目的,或者能否诉诸武力行动(像格林纳达事件那样),它为此而煞费苦心。

By far the most worrying situation of all, however, lies just to the south of the United States, and makes the Polish “crisis” for the USSR seem small by comparison. There is simply no equivalent in the world for the present state of Mexican-United States relations. Mexico is on the verge of economic bankruptcy and default, its internal economic crisis forces hundreds of thousands to drift illegally to the north each year, its most profitable trade with the United States is swiftly becoming a brutally managed flow of hard drugs, and the border for all this sort of traffic is still extraordinarily permeable. 210

然而,最令人忧虑的问题还在美国的南边,这一问题使得苏联面临的波兰“危机”都显得黯然失色。美墨关系的现状简直是世界上独一无二的。墨西哥已处于经济崩溃和违约赖账的边缘,它国内的经济危机使得每年都有10多万墨西哥人非法流入美国,它同美国之间最有利可图的贸易突然成了残忍、野蛮地经营毒品走私,而美墨边界对于这类贩运活动仍然非常容易渗透。

If the challenges to American interests in East Asia are farther away, that does not diminish the significance of this vast area today. The largest share of the world’s population lives there; a large and increasing proportion of American trade is with countries on the “Pacific rim”; two of the world’s future Great Powers, China and Japan, are located there; the Soviet Union, directly and (through Vietnam) indirectly, is also there. So are those Asian newly industrializing countries, delicate quasi-democracies which on the one hand have embraced the capitalist laissez-faire ethos with a vengeance, and on the other are undercutting American manufacturing in everything from textiles to electronics. It is in East Asia, too, that a substantial number of American military obligations exist, usually as creations of the early Cold War.

如果说对美国远东利益的挑战还很遥远的话,那么这并不能削弱东亚这一广大地区在今天的重大意义。远东居住着世界上最多的人口,美国对外贸易中最重要的并且日益增长的部分,正是同“太平洋周边”国家进行的;世界上未来的两大国——中国和日本就位于此地;苏联也直接和间接(通过越南)地属于远东地区。该地区还有一些新兴的工业化国家,一方面,它们脆弱的准民主制度彻底地接受了资本主义的自由主义经济原则;另一方面,它们又都削低价格与美国的工业制品进行竞争,从纺织到电子无不如此。正是在远东地区,美国一直承担着大量的军事义务,这作为早期“冷战”的产物一直存在着。

Even a mere listing of those obligations cannot fail to suggest the extraordinarily wide-ranging nature of American interests in this region. A few years ago, the U. S. Defense Department attempted a brief summary of American interests in East Asia, but its very succinctness pointed, paradoxically, to the almost limitless extent of those strategical commitments:

即使仅仅把这些义务列一个清单,也能揭示出美国远东利益的那种非同寻常和范围广泛的特点。几年以前,美国国防部试图就其在远东的利益问题准备一份概要文件,而它那十分简洁的文字却披露出那些战略义务的无限范围:

The importance to the United States of the security of East Asia and the Pacific is demonstrated by the bilateral treaties with Japan, Korea, and the Philippines; the Manila Pact, which adds Thailand to our treaty partners; and our treaty with Australia and New Zealand—the ANZUS Treaty. It is further enhanced by the deployment of land and air forces in Korea and Japan, and the forward deployment of the Seventh Fleet in the Western Pacific. Our foremost regional objectives, in conjunction with our regional friends and allies, are:

东亚和太平洋地区的安全对于美国的重要意义已通过以下诸条约正式申明:同日本、韩国和菲律宾的双边条约,使泰国成为我条约成员的《马尼拉条约》,同澳大利亚和新西兰的《澳新美安全条约》。我们还通过在朝鲜和日本驻守陆空部队,将我第七舰队部署于西太平洋前沿而进一步扩大了它的意义。我们在该地区的最高目标是与友国和盟国协力做到:

—To maintain the security of our essential sea lanes and of the United States’ interests in the region; to maintain the capability to fulfill our treaty commitments in the Pacific and East Asia; to prevent the Soviet Union, North Korea, and Vietnam from interfering in the affairs of others; to build a durable strategic relationship with the People’s Republic of China; and to support the stability and independence of friendly countries. 211

——维护我重要海上航线和我在该地区利益之安全,保持我履行在太平洋和东亚所承担的义务之能力;阻止苏联、朝鲜和越南干涉他国事务;与中国建立持久的战略关系;支持友好国家的稳定和独立。

Moreover, this carefully selected prose inevitably conceals a considerable number of extremely delicate political and strategical issues: how to build a good relationship with the PRC without abandoning Taiwan; how to “support the stability and independence of friendly countries” while trying to control the flood of their exports to the American market; how to make the Japanese assume a larger share of the defense of the western Pacific without alarming its various neighbors; how to maintain U. S. bases in, for example, the Philippines without provoking local resentments; how to reduce the American military presence in South Korea without sending the wrong “signal” to the North …

进一步讲,这一段精心挑选的文字难免会掩盖很多十分微妙的政治和战略问题,比如如何同中国建立良好关系而又不放弃中国台湾;如何在尽力控制友好国家的产品流入美国市场的同时,“支持友好国家的稳定和独立”;如何使日本为保卫西太平洋的安全承担更多责任,而又不致引起日本邻国的不安;如何维持美国的海外基地(比如在菲律宾的基地),而又不激起当地人民的反美情绪;如何减少美国在韩国的军事存在,而又不至于向朝鲜传递错误“信号”……

Larger still, at least as measured by military deployments, is the American stake in western Europe—the defense of which is, more than anything else, the strategic rationale of the American army and of much of the air force and the navy. According to some arcane calculations, in fact, 50 or 60 percent of American general-purpose forces are allocated to NATO, an organization in which (critics repeatedly point out) the other members contribute a significantly lower share of their GNP to defense spending even though Europe’s total population and income are now larger than the USA’s own. 212 This is not the place to rehearse the various European counterarguments in the “burden-sharing” debate (such as the social cost which countries like France and West Germany pay in maintaining conscription), or to develop the point that if western Europe was “Finlandized” the USA would probably spend even more on defense than at the moment. 213 From an American strategical perspective, the unavoidable fact is that this region has always seemed more vulnerable to Russian pressure than, say, Japan—partly because it is not an island, and partly because on the other side of the European land frontier the USSR has concentrated the largest proportion of its land and air forces, significantly greater than what may be reasonably needed for internal-security purposes. This still may not give Russia the military capacity to overrun western Europe (see pp. 507–9), but it is not a situation in which it would be prudent to withdraw substantial U. S. ground and air forces unilaterally. Even the outside possibility that the world’s largest concentration of manufacturing production might fall into the Soviet orbit is enough to convince the Pentagon that “the security of western Europe is particularly vital to the security of the United States. ”214

更为重要的——至少按军事部署来衡量如此——还是美国在西欧的利害关系。保卫西欧是美国陆军和大部分海空力量高于一切的战略原则。根据一些秘密的统计数字,美国实际上将其一般常规部队的50%或60%派驻在北约国家,而(批评家们反复指出)北约组织的其他成员国仅仅将其国民生产总值的很小一部分用于国防开支,尽管欧洲的全部人口和总收入现已超过美国。在这里,笔者不打算重复“分摊负担”讨论中欧洲所提出的种种反对意见(诸如法国和德国这样的国家为维持征兵制所付出的社会代价之类),也不想讨论这样一种观点,即假如西欧“芬兰化”,那么美国可能会为保卫西欧拿出比现在更多的军费。从美国的战略观点来看,一个无法回避的事实是,西欧比日本似乎永远都较易受到苏联的压力,部分原因是西欧不是一个岛国,部分原因是苏联在欧洲的东部前线集中了它陆空力量的最大部分,而且明显地超过了其内部安全的合理需要。尽管如此,这仍不可能使苏联拥有横扫西欧的军事能力,但在这种情况下,要单方面陆续撤走美国的地面和空军部队,则要谨慎从事。即使西欧这一世界上工业生产最为集中的基地可能落入苏联手中的微小可能,也足以使五角大楼相信,“西欧安全对于美国的安全特别重要”。

Yet however logical the American commitment to Europe may be strategically, that fact itself is no guarantee against certain military and political complications which have led to transatlantic discord. Although the NATO alliance brings the United States and western Europe close together at one level, the EEC itself is, like Japan, a rival in economic terms, especially in the shrinking markets for agricultural products. More significantly, while official European policy has always been to stress the importance of being under the American “nuclear umbrella,” a broad-based unease exists among the general publics at the implications of siting U. S. weapons (cruise missiles, Pershing lis, Trident-bearing submarines—let alone neutron bombs) on European soil. But if, to return to an earlier point, both superpowers would try to avoid “going nuclear” in the event of a major clash, that still leaves considerable problems in guaranteeing the defense of western Europe by conventional means. In the first place, that is a very expensive proposition. Secondly, even if one accepts the evidence which is beginning to suggest that the Warsaw Pact’s land and air forces could in fact be held in check, such an argument is predicated upon a certain enhancement of NATO’s current strength. From that perspective, nothing could be more upsetting than proposals to reduce or withdraw U. S. forces in Europe— however pressing that might be for economic reasons or for the purpose of buttressing American deployments elsewhere in the world. Yet carrying out a grand strategy which is both global and flexible is extremely difficult when so large a portion of the American armed forces are committed to one particular region.

但是,不管美国对欧洲所承担的义务在战略上多么合乎逻辑,这一事实本身并不能保证某种军事和政治纠纷不会导致大西洋两岸的不和。虽然北约组织在某种程度上把美国和西欧紧密联在一起,但是从经济上讲,尤其是在农产品市场日益缩小的情况下,欧共体本身也像日本一样,是美国的竞争对手。意义更为深远的是,尽管欧洲官方政策一直强调躲在美国“核保护伞”下的重要性,但是欧洲公众对于在自己的土地上部署美国武器(巡航导弹、潘兴Ⅱ式导弹、载有三叉戟导弹的潜艇,更不消说中子弹)的后果,仍然深感不安。但是,(又回到前面谈过的问题)假如两个超级大国在一场大规模的冲突中避免“跨越核门槛”,那么这对于使用常规手段保卫西欧仍然存在许多难题。首先,使用常规手段费用十分昂贵。其次,即使有根据表明华约的地面和空中部队事实上可以被牵制住,这种观点也意味着北约现有兵力必须得到加强。依照这种观点,没有任何事情能比减少或撤走美国驻欧军队更令人担心的了,不管这么做的经济理由和加强美国在世界其他地区的军事部署的要求多么迫切。但是,在美国如此众多的武装部队投入西欧这一特定地区的情况下,要想推行一种既是全球性又具灵活性的大战略,确实极其困难。

In view of the above, it is not surprising that the circles most concerned about the discrepancy between American commitments and American power are the armed services themselves, simply because they would be the first to suffer if strategical weaknesses were exposed in the harsh test of war. Hence the frequent warnings by the Pentagon against being forced to carry out a global logistical juggling act, switching forces from one “hot spot” to another as new troubles emerge. If this was particularly acute in late 1983, when additional U. S. deployments in Central America, Grenada, Chad, and the Lebanon caused the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to proclaim that the “mismatch” between American forces and strategy “is greater now than ever before,”215 the problem had been implicit for years beforehand. Interestingly, such warnings about the American armed forces being “at full stretch” are attended by maps of “Major U. S. Military Deployment Around the World”216 which, to historians, look extraordinarily similar to the chain of fleet bases and garrisons possessed by that former world power, Great Britain, at the height of its strategic overstretch. 217

考虑到上述情况,最关心美国力量与其所承担的义务之间脱节现象的,竟是武装部队本身,这就毫不奇怪了。因为,如果美国的战略弱点在一场战争的严酷考验中暴露无遗,那么他们将是第一个受害者。有鉴于此,五角大楼不时发出这样的警告,即它正被迫从事一场全球范围的“后勤供应大搬家”的游戏,一有新的麻烦,它就将部队从一个“热点”转移到另一个“热点”。1983年,美国在中美、格林纳达、乍得和黎巴嫩进行的重新部署,致使前参谋长联席会议主席疾呼美国兵力与战略之间的“搭配不当”,“比以往任何时候都更加严重”。果真如此,那么问题也是在多年以前就已存在了。对于历史学家来说,有趣的是,给美国武装部队“伸展过度”的警告配上“美国全球主要军事部署图”,酷似以前的世界大国——大英帝国在其战略扩张达到顶峰时期所拥有的遍布全球的海军基地和驻军分布。

On the other hand, it is hardly likely that the United States would be called upon to defend all of its overseas interests simultaneously and without the aid of a significant number of allies—the NATO members in western Europe, Israel in the Middle East, and, in the Pacific, Japan, Australia, possibly China. Nor are all the regional trends becoming unfavorable to the United States in defense terms; for example, while aggression by the unpredictable North Korean regime is always possible, that would hardly be welcomed by Peking nowadays—and, in addition, South Korea itself has grown to possess over twice the population and four times the GNP of North Korea. In the same way, while the expansion of Russian forces in the Far East is alarming to Washington, that is considerably balanced off by the growing threat posed by the PRC to Russia’s land and sea lines of communication with the Orient. The recent, sober admission by the U. S. defense secretary that “we can never afford to buy the capabilities sufficient to meet all of our commitments with one hundred percent confidence”218 is surely true; but it may be less worrying than at first appears if it is also recalled that the total of potential anti-Soviet resources in the world (United States, western Europe, Japan, PRC, Australasia) is far greater than the total of resources lined up on Russia’s side.

从另一方面来讲,要求美国同时保卫其所有海外利益而又没有一些盟友的帮助——比如说西欧的北约成员国,中东的以色列,太平洋的日本、澳大利亚,可能的话还有中国——几乎是不可能的。而所有的地区性倾向在防卫方面也不可能都对美国不利,比如说,尽管捉摸不定的朝鲜对南方进攻的可能性一直存在,但这种行为将不会受到中国的欢迎;另外,韩国本身已经拥有了两倍于朝鲜的人口和4倍于朝鲜的国民生产总值这样雄厚的实力。同样,虽然苏联在远东的势力扩张总是引起华盛顿的大惊小怪,但是中国对苏联通往远东的海陆交通线已构成越来越大的威胁,这在很大程度上可以抵消苏联扩张的威胁。美国国防部长已清醒地承认:“我们永远也不能以百分之百的信心有效地满足我们承担的所有义务。”这一认识是十分正确的,但是,假如我们能够考虑到世界上潜在的反苏力量(美、西欧、日、中、澳)的总和远远大于站在苏联一边的力量总和,那么问题就可能不像初看起来那样令人担忧了。

Despite such consolations, the fundamental grand-strategical dilemma remains: the United States today has roughly the same massive array of military obligations across the globe as it had a quarter-century ago, when its shares of world GNP, manufacturing production, military spending, and armed forces personnel were so much larger than they are now. 219 Even in 1985, forty years after its triumphs of the Second World War and over a decade after its pull-out from Vietnam, the United States had 520,000 members of its armed forces abroad (including 65,000 afloat). 220 That total is, incidentally, substantially more than the overseas deployments in peacetime of the military and naval forces of the British Empire at the height of its power. Nevertheless, in the strongly expressed opinion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and of many civilian experts,221 it is simply not enough. Despite a near-trebling of the American defense budget since the late 1970s, there has occurred a “mere 5 percent increase in the numerical size of the armed forces on active duty. ”222 As the British and French military found in their time, a nation with extensive overseas obligations will always have a more difficult “manpower problem” than a state which keeps its armed forces solely for home defense; and a politically liberal and economically laissez-faire society—aware of the unpopularity of conscription—will have a greater problem than most. 223

尽管有此安慰,美国大战略的基本困境仍然存在:今日美国几乎承担着同它在1/4世纪以前同样多的义务,而当时它在世界国民生产总值、工业产量、军费开支和武装部队总人数中所占的比重,都比现在要大得多。即使在它赢得第二次世界大战40年后和它从越南脱身10多年后的1985年,美国在国外驻守的武装部队仍达52万人(包括6.5万名海军人员)。顺便指出,这个总数实质上已大大超过了鼎盛时期的大英帝国在平时的海外陆海军驻军总数。然而,按照参谋长联席会议和许多文职专家所强烈陈述的意见,这点儿人根本不够。尽管从20世纪70年代末以来美国的国防预算已增加了两倍,但是它的“现役武装部队的人数只增加了5%”。正如英国和法国在其帝国时期所发现的那样,一个承担有广泛海外义务的国家,比起一个只是为了本土防御而保持武装部队的国家来说,始终都面临一个更为难办的“人力问题”;而且,在一个政治上自由和经济上放任的社会里,由于征兵不得人心,这一问题也就格外严重。

Possibly this concern about the gap between American interests and capabilities in the world would be less acute had there not been so much doubt expressed— since at least the time of the Vietnam War—about the efficiency of the system itself. Since those doubts have been repeatedly aired in other studies, they will only be summarized here; this is not a further essay on the hot topic of “defense reform. ”224 One major area of contention, for example, has been the degree of interservice rivalry, which is of course common to most armed forces but seems more deeply entrenched in the American system—possibly because of the relatively modest powers of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, possibly because so much more energy appears to be devoted to procurement as opposed to strategical and operational issues. In peacetime, this might merely be dismissed as an extreme example of “bureaucratic politics”; but in actual wartime operations—say, in the emergency dispatch of the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force, which contains elements from all four services—a lack of proper coordination could be fatal.

如果没有对美国制度本身的效率提出——至少是从越战以来——如此众多的怀疑,那么这种对它在世界范围内利益和能力之间存在的差距的担心,也许还不太强烈。由于这些问题在其他的研究中都被反复讨论过,这里只对它们进行简要的概括,也不对“国防改革”这一热门话题作进一步讨论。例如,长期以来争论的一个主要领域一直是军种之间的竞争程度,尽管这一问题在许多国家的军队中普遍存在,但在美国体制中似乎根深蒂固。原因可能在于参谋长联席会议主席的权力相对微弱,还可能在于同战略和作战领域相比,要把大量的精力用于武器采购。在和平时期,我们可以把它作为“官僚政治”的一个极端典型而不予重视,但在实际的战争时期,比如说,在紧急情况下派遣包括4个军种的快速部署联合特混编队,如没有适当的协调,就可能造成致命后果。

In the area of military procurement itself, allegations of “waste, fraud and abuse”225 have been commonplace. The various scandals over horrendously expensive, underperforming weapons which have caught the public’s attention in recent years have plausible explanations: the lack of proper competitive bidding and of market forces in the “military-industrial complex,” and the tendency toward “gold-plated” weapon systems, not to mention the striving for large profits. It is difficult, however, to separate those deficiencies in the procurement process from what is clearly a more fundamental happening: the intensification of the impacts which new technological advances make upon the art of war. Given that it is in the high-technology field that the USSR usually appears most vulnerable—which suggests that American quality in weaponry can be employed to counter the superior Russian quantity of, say, tanks and aircraft—there is an obvious attraction in what Caspar Weinberger termed “competitive strategies” when ordering new armaments. 226 Nevertheless, the fact that the Reagan administration in its first term spent over 75 percent more on new aircraft than the Carter regime but acquired only 9 percent more planes points to the appalling military-procurement problem of the late twentieth century: given the technologically driven tendency toward spending more and more money upon fewer and fewer weapon systems, would the United States and its allies really have enough sophisticated and highly expensive aircraft and tanks in reserve after the early stages of a ferociously fought conventional war? Does the U. S. Navy possess enough attack submarines, or frigates, if heavy losses were incurred in the early stages of a third Battle of the Atlantic? If not, the results would be grim; for it is clear that today’s complex weaponry simply cannot be replaced in the short times which were achieved during the Second World War.

就军事采购这一领域来讲,所谓“浪费、弄虚作假和滥用职权”的批评也是司空见惯的。近年来造价昂贵但性能不合要求的武器引起公众关注,出现了种种丑闻,其原因有诸多合理的解释,例如在“军工部门”中缺乏适当的投标竞争和市场力量,武器系统本身“日益昂贵”的倾向,何况还有军火商对高额利润的追求等。但是,把采购过程中的缺陷同正在发生的明显而根本的变革——新的技术进步对战争艺术带来的广泛影响——割裂开来是很困难的。尽管在高科技领域苏联通常是最脆弱的——这表明美国武器的质量可以抵消苏联武器如坦克和飞机数量的优势——但是,卡斯帕·温伯格就采购新的武器装备而提出的“竞争战略”,仍具有明显的诱人之处。不过,里根政府在其第一任期内比卡特政府在飞机上多支出75%的军费而最终只多得了9%的飞机这一事实,揭示了20世纪末期美国军事采购中存在的这一令人震惊的问题:假使技术进步的逻辑迫使人们花费越来越多的金钱,却只能得到越来越少的武器系统。那么在一场激烈的常规战争初期过后,美国及其盟国是否还真能准备起充足的、先进而造价昂贵的飞机和坦克呢?如果美国海军在一场第三次大西洋海战中的初期阶段就遭受惨重损失,它是否还有足够的攻击潜艇或护卫舰呢?如果没有,结果将是不堪设想的,因为十分明显,当今武器的复杂性使得武器本身难以像第二次世界大战时期那样在短期内就得到更换。

This dilemma is accentuated by two other elements in the complicated calculus of evolving an effective American defense policy. The first is the issue of budgetary constraints. Unless external circumstances became much more threatening, it would be a remarkable act of political persuasion to get national defense expenditures raised much above, say, 7. 5 percent of GNP—the more especially since the size of the federal deficit (see below, pp. 527–28) points to the need to balance governmental spending as the first priority of state. But if there is a slowing-down or even a halt in the increase in defense spending, coinciding with the continuous upward spiral in weapons costs, then the problem facing the Pentagon will become much more acute.

这一困境又因制定美国国防政策这一复杂过程中的两个因素而更显严重。首先是预算的限制,除非外部环境对自身构成了日益严重的威胁,否则要想争取国防开支有比以往较大的提高,比如增加到国民生产总值的7.5%,那将是一场异乎寻常的政治游说;特别是由于联邦赤字的规模迫使美国将平衡政府开支作为首要问题之后,增加军费开支更为困难。但是,假如国防开支增长速度的下降或者干脆停止,恰好同武器费用的攀升碰到一起,那么五角大楼面临的困难将会雪上加霜。

The second factor is the sheer variety of military contingencies that a global superpower like the United States has to plan for—all of which, in their way, place differing demands upon the armed forces and the weaponry they are likely to employ. This again is not without precedent in the history of the Great Powers; the British army was frequently placed under strain by having to plan to fight on the Northwest Frontier of India or in Belgium. But even that challenge pales beside the task facing today’s “number one. ” If the critical issue for the United States is preserving a nuclear deterrent against the Soviet Union, at all levels of escalation, then money will inevitably be poured into such weapons as the MX missile, the B-l and “Stealth” bombers, Pershing lis, cruise missiles, and Trident-bearing submarines. If a large-scale conventional war against the Warsaw Pact is the most probable scenario, then the funds presumably need to go in quite different directions: tactical aircraft, main battle tanks, large carriers, frigates, attack submarines, and logistical services. If it is likely that the United States and the USSR will avoid a direct clash, but that both will become more active in the Third World, then the weapons mix changes again: small arms, helicopters, light carriers, an enhanced role for the U. S. Marine Corps become the chief items on the list. Already it is clear that a large part of the controversy over “defense reform” stems from differing assumptions about the type of war the United States might be called upon to fight. But what if those in authority make the wrong assumption?

其次,像美国这样一个全球超级大国所必须应付的军事突发事件错综复杂、多种多样;每一种不同的事件对所需的武装部队和武器都有不同的要求。这一点在大国的历史上不是没有先例。当年的英国陆军由于不得不在印度东北边境或在比利时作战,曾经常处于捉襟见肘的困境之中。但是这种挑战比起今日“头号”强国所面临的艰难任务,只能是小巫见大巫。如果美国的关键问题是在各种水平上保持对苏联的核威慑,那么它就必然会把大量金钱投在诸如MX导弹、B-I和“隐形”轰炸机、潘兴Ⅱ式导弹、巡航导弹、载三叉戟导弹的潜艇之类的武器上。如果同华沙条约集团打一场大规模的常规战争是最有可能的方案,那么资金大概就要流向完全不同的方向:战术飞机、主战坦克、大型航母、护卫舰、攻击潜艇以及后勤保障建设。假如美苏避免直接相撞但有可能在第三世界激烈角逐,则所需武器就会混合搭配:小型武器、直升机、轻型航母以及美国海军陆战队将得到加强并成为中坚力量。由此可见,有关“国防改革”的大量争论来自对美国可能应付的战争类型的不同估计。但是,如果政府决策人士估计错误,后果又将如何呢?

A further major concern about the efficiency of the system, and one voiced even by strong supporters of the campaign to “restore” American power,227 is whether the present decision-making structure permits a proper grand strategy to be carried out. This would not merely imply achieving a greater coherence in military policies, so that there is less argument about “maritime strategy” versus “coalition warfare,”228 but would also involve effecting a synthesis of the United States’ longterm political, economic, and strategical interests, in place of the bureaucratic infighting which seems to have characterized so much of Washington’s policymaking. A much-quoted example of this is the all-too-frequent public dispute about how and where the United States should employ its armed forces abroad to enhance or defend its national interests—with the State Department wanting clear and firm responses made to those who threaten such interests, but the Defense Department being unwilling (especially after the Lebanon debacle) to get involved overseas except under special conditions. 229 But there also have been, and by contrast, examples of the Pentagon’s preference for taking unilateral decisions in the arms race with Russia (e. g. , SDI program, abandoning SALT II) without consulting major allies, which leaves problems for the State Department. There have been uncertainties attending the role played by the National Security Council, and more especially individual national security advisers. There have been incoherencies of policy in the Middle East, partly because of the in-tractibility of, say, the Palestine issue, but also because the United States’ strategical interest in supporting the conservative, pro-Western Arab states against Russian penetration in that area has often foundered upon the well-organized opposition of its own pro-Israel lobby. There have been interdepartmental disputes about the use of economic tools—from boycotts on trade and embargoes on technology transfer to foreign-aid grants and weapons sales and grain sales—in support of American diplomatic interests, which affect policies toward the Third World, South Africa, Russia, Poland, the EEC, and so on, and which have sometimes been uncoordinated and contradictory. No sensible person would maintain that the many foreign-policy problems afflicting the globe each possess an obvious and ready “solution”; on the other hand, the preservation of long-term American interests is certainly not helped when the decision-making system is attended by frequent disagreements within.

进一步讲,对美国这种体制效率的主要担心——甚至“重振”国威的坚决支持者们都如此表示——在于现行的决策体系能否保证推行一个适当的大战略。这不仅意味着要实现军事政策上更大的连贯性,以减少“海洋战略”和“联盟作战”之间的争吵,而且还要求实现美国长远的政治经济和战略利益之间的协调一致,以取代已成为华盛顿决策重要特点的官僚内斗。关于这一点,一个常被引用的例子就是,决策部门之间对于美国在海外怎样和在何地使用其武装部队,以加强或是保卫其国家利益的频繁的公开争执——国务院要求对威胁到这些利益的行为做出明确而坚决的反应,而国防部则不情愿(特别是在黎巴嫩的冒险失败以后)卷入海外麻烦,除非有特殊情况。但是,五角大楼也有过与此相反的例子,即它偏爱在同苏联的军备竞赛中事先不同主要盟国协商就单方面做出决定(比如战略防御计划SDI和主动违反第二阶段限制战略武器条约),这却给国务院留下不少难题。对于国家安全委员会,尤其是国家安全顾问个人的地位,也有不少使人难以捉摸的问题。美国对中东的政策也常常是零打碎敲、前后不一,这部分是由于存在十分棘手的巴勒斯坦问题,部分是由于美国在支持保守的、亲西方的阿拉伯国家以抵制苏联对该地区的渗透方面的战略利益,常常受到其国内亲以色列院外集团有组织的激烈反对和冲击。在如何运用经济手段(从贸易制裁、禁止转让技术到外援许可证、武器销售和粮食出口)支持美国的外交利益方面(这些利益影响到对第三世界、南非、苏联、波兰、欧共体等国家和地区的政策),各部门、机构之间经常争执不下,致使各项政策之间有时互不协调、相互矛盾。一方面,任何明智的人都不会坚持认为,每一个困扰世界的对外政策问题都有一个明显而现成的“解决办法”;另一方面,决策体制内部经常发生分歧,对保护美国的长远利益肯定没有帮助。

All this has led to questions by gloomier critics about the overall political culture in which Washington decision-makers have to operate. This is far too large and complex a matter to be explored in depth here. But it has been increasingly suggested that a country needing to reformulate its grand strategy in the light of the larger, uncontrollable changes taking place in world affairs may not be well served by an electoral system which seems to paralyze foreign-policy decision-making every two years. It may not be helped by the extraordinary pressures applied by lobbyists, political action committees, and other interest groups, all of which, by definition, are prejudiced in respect to this or that policy change; nor by an inherent “simplification” of vital but complex international and strategical issues through a mass media whose time and space for such things are limited, and whose raison d’être is chiefly to make money and secure audiences, and only secondarily to inform. It may also not be helped by the still-powerful “escapist” urges in the American social culture, which may be understandable in terms of the nation’s “frontier” past but is a hindrance to coming to terms with today’s more complex, integrated world and with other cultures and ideologies. Finally, the country may not always be assisted by its division of constitutional and decision-making powers, deliberately created when it was geographically and strategically isolated from the rest of the world two centuries ago, and possessed a decent degree of time to come to an agreement on the few issues which actually concerned “foreign” policy, but which may be harder to operate when it has become a global superpower, often called upon to make swift decisions vis-à-vis countries which enjoy far fewer constraints. No single one of these presents an insuperable obstacle to the execution of a coherent, long-term American grand strategy; their cumulative and interacting effect is, however, to make it much more difficult than otherwise to carry out needed changes of policy if that seems to hurt special interests and occurs in an election year. It may therefore be here, in the cultural and domestic-political realms, that the evolution of an effective overall American policy to meet the twenty-first century will be subjected to the greatest test.

所有这些问题使得那些悲观的批评家对华盛顿决策者活动于其中的整个政治体制提出怀疑。这是一个过于庞大而复杂的问题,难以在这里深入探讨。但它日益表明,对于一个需要依据世界事务中难以驾驭的巨大变化来修订其大战略的国家来说,每隔两年都可能造成外交决策停顿的这种选举制度,可能没有多大好处;由院外集团、政治行动委员会及其他利益集团这些对不同的政策变化明显抱有偏见的团体所施加的强大压力,也可能于事无补。大众传播媒介对重要而复杂的国际和战略问题所固有的“简单化”倾向——它们关注这些问题的时间和空间有限;其存在的目的主要在于赚钱和招徕读者和听众,报道本身的客观性并不重要——恐怕也无助于国家。在美国社会文化中势力仍然强大的“逃避现实责任”的心理倾向,对当今美国更不会有什么裨益,尽管就美国昔日的“边疆”眼光来看是可以理解的,但对于适应今日日益复杂和一体化的世界以及同其他文化和意识形态的交往,却是一个障碍。最后,美国也不可能永远受其分权体制,即立法权与决策权分立这种体制的帮助,因为分权原则是200多年前美国在地理和战略上尚与世隔绝的情况下谨慎确立的;而且当时有充裕的时间,能对寥寥无几的真正算得上“对外”政策的问题达成一致意见。但是,在它已成为一个全球超级大国,又常常不得不迅速调整对那些几乎不受什么束缚的独立国家的政策的今天,要做到这一点已是日益困难。在这些难题中,对实施一项前后一致的、长远的美国大战略构成难以克服的障碍的已不止一个;而它们的不断积累和相互作用的结果,则使得在选举年对那些看来有损于某些特殊利益的政策进行必要的调整,比不作调整更加困难。因此,也许正是在文化和国内政治领域里,为迎接21世纪而发展和完善一项有效的美国总体政策,将受到最大的考验。

The final question about the proper relationship of “means and ends” in the defense of American global interests relates to the economic challenges bearing down upon the country, which, because they are so various, threaten to place immense strains upon decision-making in national policy. The extraordinary breadth and complexity of the American economy makes it difficult to summarize what is happening to all parts of it—especially in a period when it is sending out such contradictory signals. 230 Nonetheless, the features which were described in the preceding chapter (pp. 432–35) still prevail.

有关保卫美国全球利益的“手段与目的”之间适当关系的最后一个问题,同逼近美国的经济挑战密切相关,因为经济方面的问题复杂多样,已对制定国家政策构成无比的压力和威胁。美国经济的广泛性和复杂性使我们很难对各个方面所发生的变化做一概括,特别是在它不断发出矛盾信号的时期里,尤为困难。尽管如此,在上一篇中所描述的一切特征仍然适用。

The first of these is the country’s relative industrial decline, as measured against world production, not only in older manufactures such as textiles, iron and steel, shipbuilding, and basic chemicals, but also—although it is far less easy to judge the final outcome of this level of industrial-technological combat—in global shares of robotics, aerospace, automobiles, machine tools, and computers. Both of these pose immense problems: in traditional and basic manufacturing, the gap in wage scales between the United States and newly industrializing countries is probably such that no “efficiency measures” will close it; but to lose out in the competition in future technologies, if that indeed should occur, would be even more disastrous. In late 1986, for example, a congressional study reported that the U. S. trade surplus in high-technology goods had plunged from $27 billion in 1980 to a mere $4 billion in 1985, and was swiftly heading into a deficit. 231

第一个特征是,与世界生产相比,美国工业相对衰落。不仅在旧的制造业(如纺织、钢铁、造船)和基础化学领域是这样,而且在世界的人工智能、航天、汽车、机床和计算机领域所占的比重中也是如此,尽管现在很难判断经济技术领域里竞争的最后结果。在以上两个领域里,美国都存在大量问题:在传统的基础工业方面,美国同新兴的工业化国家之间在工资水准上的差别很大,任何“提高效率的措施”恐怕都难以奏效;如果美国在未来技术的竞争中真的输掉(如果这种情况真的发生),那么情况就会更加糟糕。例如,1986年末,美国国会的一份研究报告曾经指出,美国在高科技产品方面的贸易盈余已从1980年的270亿美元减少到1985年的40亿美元,而且正在迅速走向亏损。

The second, and in many ways less expected, sector of decline is agriculture. Only a decade ago, experts in that subject were predicting a frightening global imbalance between feeding requirements and farming output. 232 But such a scenario of famine and disaster stimulated two powerful responses. The first was a massive investment into American farming from the 1970s onward, fueled by the prospect of ever-larger overseas food sales; the second was the enormous (western-world-funded) investigation into scientific means of increasing Third World crop outputs, which has been so successful as to turn growing numbers of such countries into food exporters, and thus competitors of the United States. These two trends are separate from, but have coincided with, the transformation of the EEC into a major producer of agricultural surpluses, because of its price-support system. In consequence, experts now refer to a “world awash in food,” 233 which in turn leads to sharp declines in agricultural prices and in American food exports—and drives many farmers out of business.

衰落的第二个部门(一般也是人们很少料到的)就是农业。仅10年前,农业专家们还在预言,在粮食需求和农业产量之间将会出现全球性的不平衡。但是,他们所预测的这种饥荒和灾难的前景,反而招致两种强烈的反应。其一是在海外食物销售无限广阔的前景刺激下,美国从20世纪70年代开始对农业进行大规模投资;其二就是,在西方世界的资助下,进行大量研究,以便用科学方法提高第三世界的谷物产量。这项工作十分成功,以至于使越来越多的第三世界国家成了粮食出口国,因而也自然成了美国的竞争者。这两种趋势同欧共体因其价格补贴体制而成为过剩农产品生产者的过程殊途同归。结果专家们现在转而提出了“世界充满着食物”之说,这又反过来导致了农产品价格和美国粮食出口的急剧下跌,也迫使许多农场主停产歇业。

It is not surprising, therefore, that these economic problems have led to a surge in protectionist sentiment throughout many sectors of the American economy, and among businessmen, unions, farmers, and their congressmen. As with the “tariff reform” agitation in Edwardian Britain,234 the advocates of increased protection complain of unfair foreign practices, of “dumping” below-cost manufactures on the American market, and of enormous subsidies to foreign farmers—which, they maintain, can only be answered by U. S. administrations abandoning their laissezfaire policy on trade and instituting tough counter measures. Many of those individual complaints (e. g. , of Japan shipping below-cost silicon chips to the American market) have been valid. More broadly, however, the surge in protectionist sentiment is also a reflection of the erosion of the previously unchallenged U. S. manufacturing supremacy. Like mid-Victorian Britons, Americans after 1945 favored free trade and open competition, not just because they held that global commerce and prosperity would be boosted in the process, but also because they knew that they were most likely to benefit from the abandonment of protectionism. Forty years later, with that confidence ebbing, there is a predictable shift of opinion in favor of protecting the domestic market and the domestic producer. And, just as in that earlier British case, defenders of the existing system point out that enhanced tariffs might not only make domestic products less competitive internationally, but that there also could be various external repercussions—a global tariff war, blows against American exports, the undermining of the currencies of certain newly industrializing countries, and a return to the economic crisis of the 1930s.

因此毫不奇怪,正是这些经济问题导致了遍及美国经济各部门和弥漫于商人、工会、农场主及其各自的国会议员之间的保护主义浪潮。正如英国爱德华七世时期的“关税改革”之争一样,加强保护措施的辩护者抱怨外国所进行的不公正行为和低成本制品在美国的倾销,谴责国外对农场主的大量补贴;而且坚持认为,只有美国政府放弃对贸易的不干涉政策并实行强硬的反倾销措施,才能应对这些国外竞争的压力。他们的许多怨言(比如日本廉价硅片充斥美国市场)都是有道理的。广义上说,这种保护主义情绪恰恰反映了曾是天下无敌的美国制造业优势地位的衰落。犹如维多利亚时期的英国一样,1945年后的美国支持自由贸易和公开竞争,不仅是由于他们垄断了全球商业以及由此带来了繁荣,而且因为他们懂得,如果消除保护主义,那么最有可能受惠的是他们自己。但是40年后,随着这种自信心的下降,美国的观点将转向保护国内市场和国内生产者。总之,正像英帝国早期的情况一样,现存制度的保护者总会提出,提高关税不仅可能削弱国内产品在国际上的竞争能力,而且还可能导致种种外来的不利反应,比如全球关税战、抵制美国货、一些新兴工业化国家的货币贬值,以及再次出现20世纪30年代的经济危机。

Along with these difficulties affecting American manufacturing and agriculture there are unprecedented turbulences in the nation’s finances. The uncompetitiveness of U. S. industrial products abroad and the declining sales of agricultural exports have together produced staggering deficits in visible trade—$160 billion in the twelve months to May 1986—but what is more alarming is that such a gap can no longer be covered by American earnings on “invisibles,” which is the traditional recourse of a mature economy (e. g. , Great Britain before 1914). On the contrary, the only way the United States can pay its way in the world is by importing ever-larger sums of capital, which has transformed it from being the world’s largest creditor to the world’s largest debtor nation in the space of a few years.

伴随着这些影响美国制造业和农业的问题而来的,还有国家金融领域里前所未有的动荡。美国工业制品在国外竞争力的削弱和农产品出口的下降,共同造成了美国在有形贸易方面的巨额逆差——到1986年5月为止的12个月里,逆差额为l600亿美元;更使人担心的是,这一贸易赤字再也不能用美国在“无形”贸易方面的收益来抵偿,而后者通常是成熟经济的依靠(比如1914年前的大英帝国)。恰恰相反,要维持美国在世界上的经济地位的唯一办法,只能是前所未有地大规模吸收外资,在短短几年之内,将自己从世界上最大的债权国变成最大的债务国。

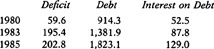

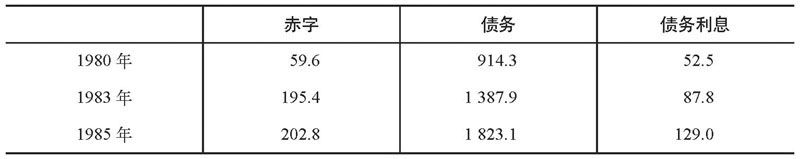

Compounding this problem—in the view of many critics, causing this problem235 —have been the budgetary policies of the U. S. government itself. Even in the 1960s, there was a tendency for Washington to rely upon deficit finance, rather than additional taxes, to pay for the increasing cost of defense and social programs. But the decisions taken by the Reagan administration in the early 1980s—i. e. , largescale increases in defense expenditures, plus considerable decreases in taxation, but without significant reductions in federal spending elsewhere—have produced extraordinary rises in the deficit, and consequently in the national debt, as shown in Table 49.

使这一问题更加复杂的是——按照某些批评家的看法,这一问题的根源是——长期以来美国政府本身的预算政策。即使在20世纪60年代,华盛顿已有这样的倾向,即依靠赤字财政而不是依靠增加税收,来支付日益庞大的国防和社会计划的开支。但是,里根政府在80年代早期的政策——如大规模地增加国防开支,大量降低税收,而在联邦开支的其他方面没有相应减少——导致了赤字的超常上升,从而也使国家债台高筑(如表49所表明的那样)。

Table 49. U.S. Federal Deficit, Debt, and Interest, 1980–1985236

表49 1980~1985年联邦赤字、债务和利息

(billions of dollars)

(单位:10亿美元)

The continuation of such trends, alarmed voices have pointed out, would push the U. S. national debt to around $13 trillion by the year 2000 (fourteen times that of 1980), and the interest payments on such debt to $1. 5 trillion (twenty-nine times that of 1980). 237 In fact, a lowering of interest rates could bring down those estimates,238 but the overall trend is still very unhealthy. Even if federal deficits could be reduced to a “mere” $100 billion annually, the compounding of national debt and interest payments by the early twenty-first century will still cause quite unprecedented totals of money to be diverted in that direction. Historically, the only other example which comes to mind of a Great Power so increasing its indebtedness in peacetime is France in the 1780s, where the fiscal crisis contributed to the domestic political crisis.

很多警告指出,这种趋势的继续发展,将使美国债务在2000年以前跃至13万亿美元(为1980年债务的14倍),为此所付的利息将上升到1.5万亿美元(为1980年的29倍)。事实上,降低利率虽可能减少这些估计数字,但整个趋势仍然十分不利。即使联邦赤字能够降到“只有”1000亿美元,到21世纪早期,国债加上利息付款仍将使美国数额空前的金钱流向同一方向。从历史上讲,大国在和平时期如此增加其负债程度的仅有的另一例子,就是18世纪80年代的法国,而当时的财政危机加速了其国内政治危机的爆发。

These American trade and federal deficits are now interacting with a new phenomenon in the world economy—what is perhaps best described as the “dislocation” of international capital movements from the trade in goods and services. Because of the growing integration of the world economy, the volume of trade both in manufactures and in financial services is much larger than ever before, and together may amount to some $3 trillion a year; but that is now eclipsed by the stupendous level of capital flows pouring through the world’s money markets, with the London-based Eurodollar market alone having a volume “at least 25 times that of world trade. ”239 While this trend was fueled by events in the 1970s (the move from fixed to floating exchange rates, the surplus funds flowing from OPEC countries), it has also been stimulated by the U. S. deficits, since the only way the federal government has been able to cover the yawning gap between its expenditures and its receipts has been to suck into the country tremendous amounts of liquid funds from Europe and (especially) Japan—turning the United States, as mentioned above, into the world’s largest debtor country by far. 240 It is, in fact, difficult to imagine how the American economy could have got by without the inflow of foreign funds in the early 1980s, even if that had the awkward consequence of sending up the exchange value of the dollar, and further hurting U. S. agricultural and manufacturing exports. But that in turn raises the troubling question about what might happen if those massive and volatile funds were pulled out of the dollar, causing its value to drop precipitously.

美国的贸易和联邦赤字现时已同世界经济中的一种新现象相互影响、相互推动,这种现象可以表述为国际资本运动同商品贸易和劳务的“脱臼”。由于世界经济日趋一体化,制成品和金融服务业的贸易量比以前任何时候都大得多,其贸易金额每年可达3万亿美元。但是,这同今日世界货币市场上资本流动的惊人规模——比如,仅伦敦的欧洲美元市场的流通量就“至少相当于世界贸易额的25倍”——比较起来,就大为逊色了。这一趋势曾受到70年代一些事态(比如固定汇率转变为浮动汇率,欧佩克成员国大量过剩的石油美元等)的刺激,也受到美国赤字的推动,因为联邦政府消除支出和收入悬殊的唯一办法,就是从欧洲和(特别是)日本吸收大量的流动资金,像上面讲过的那样,把美国变成世界上最大的债务国。事实上,没有80年代早期的外资流入,很难想象美国经济能维持下去,尽管这会引起美元汇率上升这一难以对付的后果,并进而损害美国农业和制造业产品的出口。但是,外资流入又提出了这么一个使人担心的问题:一旦数额如此巨大而又十分活跃的外资撤出美国,致使美元汇率急剧下跌,会造成什么后果呢?

The trends have, in turn, produced explanations which suggest that alarmist voices are exaggerating the gravity of what is happening to the U. S. economy and failing to note the “naturalness” of most of these developments. For example, the midwestern farm belt would be much less badly off had not so many individuals bought land at inflated prices and excessive interest rates in the late 1970s. Again, the move from manufacturing into services is an understandable one, which is occurring in all advanced countries; and it is also worth recalling that U. S. manufacturing output has been rising in absolute terms, even if employment (especially blue-collar employment) in manufacturing industry has been falling—but that again is a “natural” trend, as the world increasingly moves from material-based to knowledge-based production. Similarly, there is nothing wrong in the metamorphosis of American financial institutions into world financial institutions, with a triple base in Tokyo, London, and New York, to handle (and profit from) the great volume of capital flows; that can only boost the nation’s earnings from services. Even the large annual federal deficits and the mounting national debt are sometimes described as being not too serious, after allowance is made for inflation; and there exists in some quarters a belief that the economy will “grow its way out” of these deficits, or that measures will be taken by the politicians to close the gap, whether by increasing taxes or cutting spending or a combination of both. A toohasty attempt to slash the deficit, it is pointed out, could well trigger off a major recession.

这种种趋势反而说明,那种危言耸听之说夸大了美国经济问题的严重性,同时也没能指明这些发展变化的“正常性”。比如,倘若在70年代末没有这么多人以飞涨的价格和很高的利率购买土地,美国中西部农业区的经济情况可能不会太糟。另外,从制造业向服务业的转移是可以理解的,也是发生在所有发达国家里的共同现象;同时还应想到,即使制造业中的雇佣劳动力(尤其是蓝领工人)的数量一直在下降,美国制造业的绝对产量还是一直上升的。就制造业中的雇佣劳动力的减少而言,也是—种“正常”的趋势,因为世界生产正日益从材料密集型向知识密集型转变。与此相似,美国的金融机构日益转变成世界性的金融机构——世界上共有3个国际金融中心(东京、伦敦和纽约)——也没什么不好,因为它操纵着(也得益于)大量的流动资本,这只会提高美国服务业的收入。只要通货膨胀为一国特定时期所需要且允许,即使每年有大量的联邦赤字和巨额国债,问题也不会过于严重;甚至有些人还持这样的看法,认为经济自会“按自己的方式摆脱”赤字,或者政治家们会采取适当措施来减少赤字,要么提高税收,要么压缩开支,或者二者兼施。他们指出,过于草率地削减赤字的努力很可能引起大规模的衰退。

Even more reassuring are said to be the positive signs of growth in the American economy. Because of the boom in the services sector, the United States has been creating jobs over the past decade faster than at any time in its peacetime history— and certainly a lot faster than in western Europe. As a related point, its far greater degree of labor mobility eases such transformations in the job market. Furthermore, the enormous American commitment in high technology—not just in California, but in New England, Virginia, Arizona, and many other parts of the land—promises ever greater outputs of production, and thus of national wealth (as well as ensuring a strategical edge over the USSR). Indeed, it is precisely because of the opportunities that exist in the American economy that it continues to attract millions of immigrants, and to stimulate thousands of new entrepreneurs; while the floods of capital which pour into the country can be tapped for further investment, especially into R&D. Finally, if the shifts in the global terms of trade are indeed leading to lower prices for foodstuffs and raw materials, that ought to benefit an economy which still imports enormous amounts of oil, metal ores, and so on (even if it hurts particular American producers, like farmers and oilmen).

更使人宽心的,据说是美国经济中积极的增长信号。由于服务行业的繁荣,美国在过去10年中比其在和平时期的任何时候都更迅速地创造了新的就业机会——当然也比欧洲要快。与此相联系,更大规模的劳工流动也有利于就业市场的这种变化。进一步讲,美国不仅在加利福尼亚,也在新英格兰、弗吉尼亚、亚利桑那以及许多其他地方对高技术大量投资,保证了更高的产量,同时也创造了更多的国家财富(也确保了美国对苏联的某种战略优势)。事实上,正是美国经济中存在着大量的机会继续吸引着数百万的移民,激励着成千上万的企业家;而汇入美国的资本洪流也要求进一步投资,特别是在研究和开发领域。最后,如果全球贸易中的这种变化确实导致了粮食和原材料价格的下跌,那么这也应该有利于仍进口大量石油、金属矿石及其他原料的美国经济(尽管会损害像农场主和石油大王这样一些生产者)。

Many of these individual points may be valid. Since the American economy is so large and variegated, some sectors and regions are likely to be growing at the same time as others are in decline—and to characterize the whole with sweeping generalizations about “crisis” or “boom” is therefore inappropriate. Given the decline in raw-materials prices, the ebbing of the dollar’s unsustainably high exchange value of early 1985, the general fall in interest rates—and the impact of all three trends upon inflation and upon business confidence—it is not surprising to find some professional economists being optimistic about the future. 241

以上许多观点可能都有道理。因为美国经济的规模如此宏大而且多样化,因此,在一些经济部门和地区衰落的同时,其他部门和地区则可能欣欣向荣。这就使得对美国经济进行“危机”或“繁荣”的笼统概括很不恰当。因此,即使在原材料价格下降、美元难以长久支撑的高比值在1985年早期下跌和利率降低——这三种趋势都会对通货膨胀和企业界的信心产生很大影响——的情况下,你仍会发现一些经济学家对未来充满信心,这一点并不奇怪。

Nevertheless, from the viewpoint of American grand strategy, and of the economic foundation upon which an effective, long-term strategy needs to rest, the picture is much less rosy. In the first place, given the worldwide array of military liabilities which the United States has assumed since 1945, its capacity to carry those burdens is obviously less than it was several decades ago, when its share of global manufacturing and GNP was much larger, its agriculture was not in crisis, its balance of payments was far healthier, the government budget was also in balance, and it was not so heavily in debt to the rest of the world. In that larger sense, there is something in the analogy which is made by certain political scientists between the United States’ position today and that of previous “declining hegemons. ”242

不过,从美国大战略和一种有效的、长远战略必须依靠的经济基础的角度来看,前景并不那么美好。首先,美国1945年以来在全球范围内承担了大量的军事义务,但是现在它肩负这些包袱的能力明显地不如几十年前,当时它在世界工业和国民生产总值中所占的比重远远大于今天;它的农业也未陷入危机,它的国际收支也比今日健康得多,政府预算尚保持平衡,对世界其他国家所欠债务也远不如今日沉重。从这一较广的意义上来讲,一些政治科学家把今日美国的地位同往昔“衰落的霸权”相提并论是有道理的。

Here again, it is instructive to note the uncanny similarities between the growing mood of anxiety among thoughtful circles in the United States today and that which pervaded all political parties in Edwardian Britain and led to what has been termed the “national efficiency” movement: that is, a broad-based debate within the nation’s decision-making, business, and educational elites over the various measures which could reverse what was seen to be a growing uncom-petitiveness as compared with other advanced societies. In terms of commercial expertise, levels of training and education, efficiency of production, standards of income and (among the less well-off) of living, health, and housing, the “number-one” power of 1900 seemed to be losing its position, with dire implications for the country’s long-term strategic position; hence the fact that the calls for “renewal” and “reorganization” came at least as much from the Right as from the Left. 243 Such campaigns usually do lead to reforms, here and there; but their very existence is, ironically, a confirmation of decline, in that such an agitation simply would not have been necessary a few decades earlier, when the nation’s lead was unquestioned. A strong man, the writer G. K. Chesterton sardonically observed, does not worry about his bodily efficiency; only when he weakens does he begin to talk about health. 244 In the same way, when a Great Power is strong and unchallenged, it will be much less likely to debate its capacity to meet its obligations than when it is relatively weaker.

在此着重指出这一点是有益的,即今日美国知识界日益强烈的不安心情,同英国爱德华七世时期遍及各政党的忧虑心情,以及由此引起的所谓“国家效率”运动之间,存在着惊人的相似之处。这就是国家的决策、企业和教育界之间,就如何扭转与其他发达国家相比已日渐削弱的竞争力这一问题,展开的基础广泛的论争。就商业技能、训练和教育水平、生产效率、收入(不甚富裕的家庭)和生活水平、健康状况、住房以及1900年的实力“第一”几个方面来看,它正在丧失其原来的优势地位,伴随而来的还有国家长远战略地位的灾难性后果;因此,要求“重振”和“重组”的呼声在左派中至少同在右派中一样强烈。这种运动通常都会在社会各处导致改革;但是有讽刺意味的是,这种运动本身就是衰落的证明;而这种改革的鼓动在几十年前美国的领导地位毋庸置疑的时候是完全没有必要的。非常有影响的作家G·K·切斯特顿具有讽刺意味地评论说,一个强壮的人是不担心自己身体的,只有到了衰弱不堪时,他才开始谈论自己的健康。同样,一个世界大国在其强大而又不受任何挑战之时,比其相对衰落之时,更不可能对自己履行义务的能力展开辩论。

More narrowly, there could be serious implications for American grand strategy if its industrial base continued to shrink. Were there ever to be a large-scale future war which remained conventional (because of the belligerents’ mutual fear of triggering a nuclear holocaust), then one is bound to wonder what the impact upon U. S. productive capacities would be after years of decline in certain key industries, the erosion of blue-collar employment, and so on. In this connection, one is reminded of Hewins’s alarmed cry in 1904 about the impact of British industrial decay upon that country’s power:245

更严格地讲,如果美国的工业基础继续受到削弱,它的大战略将会受到严重影响。假如一场未来的大规模战争仍是常规性质的(由于交战双方都惧怕发生核毁灭),那么我们不禁要问:在美国某些重要工业衰退、蓝领工作减少等情况持续若干年后,美国的生产能力将会受到什么影响?与此相联系,使人不禁想起海因斯在1904年对英国工业衰退给这个国家的实力造成的影响所发出的警告:

Suppose an industry which is threatened [by foreign competition] is one which lies at the very root of your system of National defence, where are you then? You could not get on without an iron industry, a great Engineering trade, because in modern warfare you would not have the means of producing, and maintaining in a state of efficiency, your fleets and armies.

假若作为一国国防基石的工业受到(外国竞争的)威胁,那么国家处境将会怎样?没有钢铁工业,没有庞大的工程技术行业,国家就无法生存。因为在现代战争中,缺乏这些就等于丧失了生产的手段,也无法保持一支有战斗力的舰队和陆军。

It is hard to imagine that the decline in American industrial capacity could be so severe: its manufacturing base is simply that much broader than Edwardian Britain’s was; and—an important point—the “defense-related industries” have not only been sustained by repeated Pentagon orders, but have paralleled the shift from materialsintensive into knowledge-intensive (high-technology) manufacturing, which over the longer term will also reduce the West’s reliance upon critical raw materials. Even so, the very high proportion of, say, semiconductors which are assembled in foreign countries and then shipped to the United States,246 or—to think of a product as far removed from semiconductors as possible—the erosion of the American shipping and shipbuilding industry, or the closing down of so many American mines and oilfields—such trends cannot but be damaging in the event of another longlasting, Great Power, coalition war. If, moreover, historical precedents are of any validity at all, the most critical constraint upon any “surge” in wartime production has usually been in the area of skilled craftsmen247—which, once again, causes one to wonder about the massive long-term decline in American blue-collar (i. e. , usually skilled-craftsmen) employment.

很难想象美国工业能力的衰退会如此严重,因为它的工业基础比爱德华七世时期的英国要雄厚得多;而且重要的一点是,美国“与国防有关的工业”不仅受到五角大楼订货单的支撑,而且也同整个工业从材料密集型向知识密集型(即高科技)的转变并行不悖;从长远来讲,这也会减少西方对重要原料的依赖。尽管如此,大量的半导体(或者从半导体想到其他产品)在国外装配而后运回美国市场,美国的海运和造船工业衰退,许多矿井和油田关闭。一旦发生一场持久的大国之间的联盟战争,所有这些肯定会产生破坏作用。进一步讲,如果历史的先例还可供借鉴的话,那么对战时生产的“高涨”造成最严重束缚的通常是技术工人短缺问题——这又使人对美国蓝领(往往是有技术的工人)工作的大规模减少不禁疑虑重重。

A quite different problem, but one equally important for the sustaining of a proper grand strategy, concerns the impact of slow economic growth upon the American social/political consensus. To a degree which amazes most Europeans, the United States in the twentieth century has managed to avoid ostensible “class” politics. This is due, one imagines, to the facts that so many of its immigrants were fleeing from socially rigid circumstances elsewhere; that the sheer size of the country allowed those who were disillusioned with their economic position to “escape” to the West, and simultaneously made the organization of labor much more difficult than in, say, France or Britain; and that those same geographical dimensions, and the entrepreneurial opportunities within them, encouraged the development of a largely unreconstructed form of laissez-faire capitalism which has dominated the political culture of the nation (despite occasional counterattacks from the left). In consequence, the “earnings gap” between rich and poor in the United States is significantly larger than in any other advanced industrial society; and, by the same token, state expenditures upon social services form a lower share of GNP than in comparable countries (except Japan, which appears to have a much stronger family-based form of support for the poor and the aged).

另一个与支持适当的大战略同样重要的问题,涉及到经济增长缓慢对美国社会和政治一致性的影响。在某种程度上使大多数欧洲人十分惊奇的是,美国在20世纪竟然避免了公开的“阶级”政治的出现。任何人都能想到,这应归功于下列事实:大量的移民都是从世界各地严酷的社会环境中逃离出来的;美国庞大的版图容许那些对其经济地位全然绝望的人们“逃避”到美国西部,同时也使得劳工组织比在法国或英国都困难得多;同样的地理因素以及这片沃土提供给企业家的机会,鼓励了在很大程度上不受限制的自由资本主义的发展,而正是这种自由资本主义决定了美国的政治体制(除了偶尔出现的来自左派的攻击以外)。结果是,美国贫富之间的“收入差距”比任何其他发达的工业社会都大;由于同样的原因,美国用于社会公益事业的开支在其国民生产总值中所占的比例,比其他类似的国家都低(日本除外,它好像有一个很强大的以家庭为基础的、资助穷人和老人的计划)。

This lack of “class” politics despite the obvious socioeconomic disparities has obviously been helped by the fact that the United States’ overall growth since the 1930s offered the prospect of individual betterment to a majority of the population; and by the more disturbing fact that the poorest one-third of American society has not been “mobilized” to become regular voters. But given the differentiated birthrate between the white ethnic groups on the one hand and the black and Hispanic groups on the other—not to mention the changing flow of immigrants into the United States, and given also the economic metamorphosis which is leading to the loss of millions of relatively high-earning jobs in manufacturing, and the creation of millions of poorly paid jobs in services, it may be unwise to assume that the prevailing norms of the American political economy (low government expenditures, low taxes on the rich) would be maintained if the nation entered a period of sustained economic difficulty caused by a plunging dollar and slow growth. What this also suggests is that an American polity which responds to external challenges by increasing defense expenditures, and reacts to the budgetary crisis by slashing the existing social expenditures, may run the risk of provoking an eventual political backlash. As with all of the other Powers surveyed in this chapter, there are no easy answers in dealing with the constant three-way tension between defense, consumption, and investment in settling national priorities.

尽管存在着社会经济上的明显差异,但并不存在“阶级”政治,这一点显然得益于以下事实:20世纪30年代以来,美国的全面发展为大多数公民的个人生活改善提供了广阔的前景;美国社会中最穷的1/3人口没有被“动员”起来成为正式的选民。但是,假定白人同黑人和西班牙人在出生率上存在差异——何况还有流入美国的大量移民的变动,假定经济变化导致制造业中数百万高收入工作者的岗位丧失,以及服务业中低收入工作者大量涌现,在这种情况下,再得出以下结论就显得不明智了,即使美国进入一个由美元贬值和低增长造成的持续的经济困难时期,它仍能保持其主要的政治经济模式(政府低开支和富人低赋税)。这还意味着,通过增加国防开支来迎接外来挑战,通过削减现有的社会开支来对付预算危机的这种美国政体,可能要冒最终引起政治动乱的风险。考虑到本篇中所考察的其他所有大国的情况,在确定国家的优先次序过程中,如何对付国防、消费和投资之间的三重经常的紧张关系,尚没有简单易行的答案。

This brings us, inevitably, to the delicate relationship between slow economic growth and high defense spending. The debate upon “the economics of defense spending” is a highly controversial one, and—bearing in mind the size and variety of the American economy, the stimulus which can come from large government contracts, and the technical spin-offs from weapons research—the evidence does not point simply in one direction. 248 But what is significant for our purposes is the comparative dimension. Even if (as is often pointed out) defense expenditures formed 10 percent of GNP under Eisenhower and 9 percent under Kennedy, the United States’ relative share of global production and wealth was at that time around twice what it is today; and, more particularly, the American economy was not then facing the challenges to either its traditional or its high-technology manufactures. Moreover, if the United States at present continues to devote 7 percent or more of its GNP to defense spending while its major economic rivals, especially Japan, allocate a far smaller proportion, then ipso facto the latter have potentially more funds “free” for civilian investment; if the United States continues to invest a massive amount of its R&D activities into military-related production while the Japanese and West Germans concentrate upon commercial R&D; and if the Pentagon’s spending drains off the majority of the country’s scientists and engineers from the design and production of goods for the world market while similar personnel in other countries are primarily engaged in bringing out better products for the civilian consumer, then it seems inevitable that the American share of world manufacturing will steadily decline, and also likely that its economic growth rates will be slower than in those countries dedicated to the marketplace and less eager to channel resources into defense. 249

这种情况势必使我们面对低经济增长和高国防开支之间的微妙关系。对“国防开支经济学”的争论确实众说纷纭;而且——考虑到美国经济的规模和多样性,来自政府大量合同的刺激以及武器研究带来的技术进步——论据都不是简单地指向一个方向。但对我们的目的来说,最重要的是进行比较。即使美国的国防开支(正如人们常常指出的那样)在艾森豪威尔政府时期占其国民生产总值的10%,在肯尼迪政府时期占9%,当时美国在世界生产和财富中所占的比重也大约是今天的2倍;而且特别重要的是,当时美国的经济无论是传统制造业还是高科技制造业,都未遇到任何挑战。进而言之,假如美国现在继续将其国民生产总值的7%或更多一些用于国防,而它主要的经济竞争对手,特别是日本用于国防的开支仅占其国民生产总值的微小部分,那么依据这一事实,后者就可能拥有更多的“自由”资金用于民用投资;假如美国继续把大量的研究和开发工作投入与军事有关的生产,而日本和联邦德国将同样的力量集中于商业的研究和开发,而且五角大楼从商品的设计到生产过程占用了大部分的科学家和工程师,而其他国家则使同类的专业人员致力于为民用消费者研制更好的产品,那么美国在世界生产中所占的比重必定会继续下降,而且它的经济增长率将低于那些致力于市场活动且不急于将人力和财力投入国防的国家。

It is almost superfluous to say that these tendencies place the United States on the horns of a most acute dilemma over the longer term. Simply because it is the global superpower, with far more extensive military commitments than a regional Power like Japan or West Germany, it requires much larger defense forces—in just the same way as imperial Spain felt it needed a far larger army than its contemporaries and Victorian Britain insisted upon a much bigger navy than any other country. Furthermore, since the USSR is seen to be the major military threat to American interests across the globe and is clearly devoting a far greater proportion of its GNP to defense, American decision-makers are inevitably worried about “losing” the arms race with Russia. Yet the more sensible among these decision-makers can also perceive that the burden of armaments is debilitating the Soviet economy; and that if the two superpowers continue to allocate ever-larger shares of their national wealth into the unproductive field of armaments, the critical question might soon be: “Whose economy will decline fastest, relative to such expanding states as Japan, China, etc. ?” A low investment in armaments may, for a globally overstretched Power like the United States, leave it feeling vulnerable everywhere; but a very heavy investment in armaments, while bringing greater security in the short term, may so erode the commercial competitiveness of the American economy that the nation will be less secure in the long term. 250

从长远来看,这些趋势使美国处于进退维谷的困境,不过这个说法几乎是多余的。道理很简单,因为美国是一个全球超级大国,比日本或联邦德国这样地区性的大国承担着大得多的军事义务,需要更为强大的国防力量,正像西班牙帝国深感要有一支比同时代其他国家更为强大的陆军一样;而维多利亚时代的大英帝国坚持要有一支比其他任何国家都强大的海军,也说明了同一道理。不仅如此,由于苏联被美国视为其全球利益的主要威胁,而且众所周知,它正将其国民生产总值的相当大一部分投入国防,因此美国决策者势必会担心“输掉”同苏联进行的这场军备竞赛。然而,更为明智的决策者也认识到,军备的负担正把苏联的经济拖向衰败;而且认为,倘若这两个超级大国继续把更多的国家财富虚掷于军备这一非生产性领域,那么关键的问题不久将成为:“同诸如日本、中国这样迅速发展的国家相比,美苏哪个国家的经济衰退得更快?”对于像美国这样全球战线过长的大国来讲,在军备上的低投资可能使其感到危机四伏,处处易受攻击;而在军备上的大量开支尽管可能带来短期的安全,但却可能损害其经济的商业竞争能力,从而将长期地削弱美国的安全。

Here, too, the historical precedents are not encouraging. For it has been a common dilemma facing previous “number-one” countries that even as their relative economic strength is ebbing, the growing foreign challenges to their position have compelled them to allocate more and more of their resources into the military sector, which in turn squeezes out productive investment and, over time, leads to the downward spiral of slower growth, heavier taxes, deepening domestic splits over spending priorities, and a weakening capacity to bear the burdens of defense. 251 If this, indeed, is the pattern of history, one is tempted to paraphrase Shaw’s deadly serious quip and say: “Rome fell; Babylon fell; Scarsdale’s turn will come. ”252

在这里,历史的先例也不怎么鼓舞人心,因为昔日的“头号”强国都面临着共同的困境,这就是:尽管它们的相对经济实力都在下降,但对其地位日益增多的挑战却又迫使它们拿出越来越多的人力和财力投入军事领域,从而挤掉了生产性投资;随着时间的流逝,还将导致低增长和重赋税的徘徊不去,加深国内对重点开支项目的分歧,削弱其承担防卫负担的能力。如果这确实是历史发展的一种模式,那么我们禁不住要用萧伯纳的警言妙语对上述论点作如下诠释:“罗马衰落了,巴比伦衰落了,现在轮到斯卡斯代尔了。”[8]

In the largest sense of all, therefore, the only answer to the question increasingly debated by the public of whether the United States can preserve its existing position is “no”—for it simply has not been given to any one society to remain permanently ahead of all the others, because that would imply a freezing of the differentiated pattern of growth rates, technological advance, and military developments which has existed since time immemorial. On the other hand, this reference to historical precedents does not imply that the United States is destined to shrink to the relative obscurity of former leading Powers such as Spain or the Netherlands, or to disintegrate like the Roman and Austro-Hungarian empires; it is simply too large to do the former, and presumably too homogeneous to do the latter. Even the British analogy, much favored in the current political-science literature, is not a good one if it ignores the differences in scale. This can be put another way: the geographical size, population, and natural resources of the British Isles would suggest that it ought to possess roughly 3 or 4 percent of the world’s wealth and power, all other things being equal; but it is precisely because all other things are never equal that a peculiar set of historical and technological circumstances permitted the British Isles to expand to possess, say, 25 percent of the world’s wealth and power in its prime; and since those favorable circumstances have disappeared, all that it has been doing is returning down to its more “natural” size. In the same way, it may be argued that the geographical extent, population, and natural resources of the United States suggest that it ought to possess perhaps 16 or 18 percent of the world’s wealth and power, but because of historical and technical circumstances favorable to it, that share rose to 40 percent or more by 1945; and what we are witnessing at the moment is the early decades of the ebbing away from that extraordinarily high figure to a more “natural” share. That decline is being masked by the country’s enormous military capabilities at present, and also by its success in “internationalizing” American capitalism and culture. 253 Yet even when it declines to ocits “natural” share of the world’s wealth and power, a long time into the future, the United States will still be a very significant Power in a multipolar world, simply because of its size.

因此,从最广泛的意义上讲,对美国能否保持其现有的地位这一引起公众日益广泛争论的问题的唯一回答,只能是否定的,因为历史从来不曾赋予任何国家永久地超越其他社会的权利,那样将意味着冻结自远古时代以来就存在的增长率、技术进步和军事发展这种种不同模式之间的差异。另一方面,历史先例的参照并不意味着美国注定要步诸如西班牙或者荷兰这些昔日主要大国的后尘而湮没无闻,或者像罗马帝国和奥匈帝国那样土崩瓦解。美国社会太庞大了,使之不可能效法前者;美国社会内在的共生凝聚性,也使之难以重蹈后者覆辙。即使许多当代政治科学著述都将美国同英国进行类比,但是,假如它们忽视了二者在规模上的不同,那么这种类比也不会有太多的说服力。这一点可以通过以下方式加以说明:不列颠诸岛的地理面积、人口和自然资源可能表明,在其他条件都相同的情况下,它应该大致拥有世界财富和力量的3%或4%;然而恰恰由于其他条件不会相同,历史和技术环境的特殊安排才使英国在其鼎盛时期占有了世界财富和力量的25%;而自从那些有利条件一去不返之后,它的一切作为又都回到较为“正常”的规模。同样道理,人们会说美国的地理版图、人口和资源,使它本应拥有世界财富和力量的16%或18%,但是由于有利的历史和技术环境,使它在世界财富和力量中所占的比重在1945年高达40%或许更多。而我们现在所目睹的一切,也不过是它从那一非常高的地位降到一个较为“正常”位置的早期阶段而已。美国的衰落被其目前拥有的强大军事能力及其资本主义和文化在“国际化”方面的成功所掩盖。然而,即使美国衰落到占有世界财富和力量的“正常”比重,在未来相当长一段时间内,仅仅由于它的规模,美国在一个多极世界中仍将是个十分重要的大国。

The task facing American statesmen over the next decades, therefore, is to recognize that broad trends are under way, and that there is a need to “manage” affairs so that the relative erosion of the United States’ position takes place slowly and smoothly, and is not accelerated by policies which bring merely short-term advantage but longer-term disadvantage. This involves, from the president’s office downward, an appreciation that technological and therefore socioeconomic change is occurring in the world faster than ever before; that the international community is much more politically and culturally diverse than has been assumed, and is defiant of simplistic remedies offered either by Washington or Moscow to its problems; that the economic and productive power balances are no longer as favorably tilted in the United States’ direction as in 1945; and that, even in the military realm, there are signs of a certain redistribution of the balances, away from a bipolar to more of a multipolar system, in which the conglomeration of American economic-cum-military strength is likely to remain larger than that possessed by any one of the others individually, but will not be as disproportionate as in the decades which immediately followed the Second World War. This, in itself, is not a bad thing if one recalls Kissinger’s observations about the disadvantages of carrying out policies in what is always seen to be a bipolar world (see pp. 407–8); and it may seem still less of a bad thing when it is recognized how much more Russia may be affected by the changing dynamics of world power. In all of the discussions about the erosion of American leadership, it needs to be repeated again and again that the decline referred to is relative not absolute, and is therefore perfectly natural; and that the only serious threat to the real interests of the United States can come from a failure to adjust sensibly to the newer world order.

因此,在未来几十年里,美国领导者所面临的任务是清醒地认识到正在发展的广泛趋势,意识到必须很好地“处理”所有事态,以便使美国的相对衰落进行得缓慢、平稳,不致仅仅为了近利却招致远损的政策的冲击而加速。这就需要美国从上到下一致认识到,世界上正在发生的技术以及由此而来的社会经济变化,比以往任何时候都更为迅速,国际社会在政治上和文化上比以前更加多样化;这对于不论是华盛顿还是莫斯科对各自问题所提出的简单解决办法都是一种挑战;认识到世界经济和生产力的天平不会再像1945年那样倒向美国;即使在军事领域,也有迹象表明,世界的力量正在重新组合,国际格局正从两极向多极体制发展,而在这一多极化进程中,美国经济和军事的综合实力可能仍比其他任何一个国家都强大,但这种差距不会像第二次世界大战结束后的几十年里那样悬殊。如果想到基辛格对实施以两极世界为基础所制定的政策可能带来的不利影响而作的评论,那么这种变化本身并不是一件坏事;如果认识到苏联可能受到世界力量变化影响的程度,那么这更不是一件坏事。在对美国领导地位的衰落进行讨论时,有必要反复强调,这里所说的衰落是相对的,不是绝对的,因而也是完全正常的;对美国实际利益的唯一严重威胁,反倒可能来自不能明智地适应新的世界秩序。

Given the considerable array of strengths still possessed by the United States, it ought not in theory to be beyond the talents of successive administrations to arrange the diplomacy and strategy of this readjustment so that it can, in Walter Lippmann’s classic phrase, bring “into balance … the nation’s commitments and the nation’s power. ”254 Although there is no obvious, single “successor state” which can take over America’s global burdens in the way that the United States assumed Britain’s role in the 1940s, it is nonetheless also true that the country has fewer problems than an imperial Spain besieged by enemies on all fronts, or a Netherlands being squeezed between France and England, or a British Empire facing a bevy of challengers. The tests before the United States as it heads toward the twenty-first century are certainly daunting, perhaps especially in the economic sphere; but the nation’s resources remain considerable, // they can be properly organized, and if there is a judicious recognition of both the limitations and the opportunities of American power.

考虑到美国仍有相当雄厚的国家实力,要处理好这一重新调整时期的外交和战略以实现沃尔特·李普曼所讲的“国家义务和国家力量之间的平衡”,从理论上讲不应该是美国今后历届政府中精英人才力所不及的。虽然还没有一个明显的“继承国”能接过美国的全球担子,就像在20世纪40年代美国承担英国的角色那样,但是,同四面受敌的西班牙帝国相比,或者同遭受法、英夹击的荷兰相比,或是与面临一群挑战者的大英帝国相比,美国所遇到的问题确实要少得多。美国迈向2l世纪所面临的考验肯定严峻异常,尤其是在经济领域。但是,如果美国的资源能组织使用得当,对美国这个大国的局限性和机会有明智的认识,那么美国的国家力量仍是相当强大的。

Viewed from one perspective, it can hardly be said that the dilemmas facing the United States are unique. Which country in the world, one it tempted to ask, is not encountering problems in evolving a viable military policy, or in choosing between guns and butter and investment? From another perspective, however, the American position is a very special one. For all its economic and perhaps military decline, it remains, in Pierre Hassner’s words, “the decisive actor in every type of balance and issue. ”255 Because it has so much power for good or evil, because it is the linchpin of the western alliance system and the center of the existing global economy, what it does, or does not do, is so much more important than what any of the other Powers decides to do.

从某一方面来看,美国面临的困境很难说是独一无二的。我们不禁要问:世界上哪个国家在制定一项可行的军事政策,或者在大炮、黄油和投资之间进行选择的时候,不曾遇到一系列难题?但是从另一个角度讲,美国所处的地位又是十分特殊的。尽管它的经济或许还有军事都在衰落,但是,用皮埃尔·哈斯纳的话说,“在每一种平衡和重大问题上”,它仍然是“决定性的角色”。因为无论如何,美国毕竟拥有如此强大的力量(不管是好事还是坏事),因为它是西方联盟体系的柱石和目前世界经济的中心,它有所作为,或者无所作为,比任何其他大国决定干什么都重要得多。

*Which is why even Japanese firms are building factories there.

[1]?爱德华七世(1841~1910年),英国国王,维多利亚女王之子,在位期间为1901~1910年。——审校者注

*Assuming that to be the case, it is still difficult for technical reasons to suggest what that means in exact figures. Many of the statistics commonly used (e. g. , by the CIA) in international comparisons are based upon U. S. dollars and market exchange rates; thus the tumbling of the value of the dollar vis-à-vis the yen by nearly 40 percent in 1985–1986 could, by that reckoning, massively boost Japan’s GNP total as compared with the United States’ (and also as compared with the USSR’s, since its GNP is often calculated in “geometric mean dollars”). 76 Simply a rise in the yen from its present exchange value to 120 or even 100 to the dollar—which some economic experts think is its “true” rate77—would give Japan a total GNP close to the United States’ and well in excess of Russia’s. It is because of the problems caused by rapidly fluctuating exchange rates that some economists prefer to use “purchasing parity ratios,” although that measurement also has its problems.

[2]?柯尔贝尔(1619~1683年),法王路易十四即位后,柯尔贝尔任财政总监,推行重商主义政策,建树颇多。——审校者注

*It is, for example, all too easy to show the Warsaw Pact as massively superior by including, say, all of Russia’s armed forces (even those deployed against China), and by excluding, say, France’s.

[3]?腓特烈大帝(1712~1786年),普鲁士国王(1740~1786年),史称腓特烈大帝,因其整顿财政和司法,推行一系列改革,加强了普鲁士在欧洲的地位。——审校者注

[4]?这是日本公司在那里兴建工厂的原因之一。

[5]?假设情况果真如此,人们仍难以从技术上断定准确的数字意味着什么。许多通常用来进行国际比较的统计方法(如中央情报局用的),是以美元汇率为依据的。因而,1985~1986年美元兑日元的汇率曾猛跌近40%。这一情况要是应用于上述计算,同美国相比较,就会使日本的国民生产总值激增(同苏联比较也是如此,因为人们也常常以“几何式的平均美元换算数”来计算苏联的国民生产总值)。仅把日元从其目前兑美元的汇率提高到120日元(或100日元)比1美元——某些经济学家就把这一汇率看成是它的“真正的”汇率——就会使日本的国民生产总值接近美国的,大大超过苏联的。正是因为汇率的急剧变动,某些经济学家才更愿意使用“购买力平价比率”来进行计算,尽管这种计算方法也存在着问题。

[6]?理查德·科布登(1804~1865年),英国政治家和经济学家。——译者注

[7]?尼尼微为古代亚述帝国之首都,其废墟在伊拉克境内。泰尔为古代腓尼基南部的一个海港,在今黎巴嫩境内。作者在此引述这两个地方喻空无一人,已被弃置之意。——译者注

[8]?斯卡斯代尔,美国地名,此处寓意指美国。——译者注