The “European Miracle”15

四“欧洲的奇迹”

Why was it among the scattered and relatively unsophisticated peoples inhabiting the western parts of the Eurasian landmass that there occurred an unstoppable process of economic development and technological innovation which would steadily make it the commercial and military leader in world affairs? This is a question which has exercised scholars and other observers for centuries, and all that the following paragraphs can do is to present a synthesis of the existing knowledge. Yet however crude such a summary must be, it possesses the incidental advantage of exposing the main strands of the argument which permeate this entire work: namely, that there was a dynamic involved, driven chiefly by economic and technological advances, although always interacting with other variables such as social structure, geography, and the occasional accident; that to understand the course of world politics, it is necessary to focus attention upon the material and long-term elements rather than the vagaries of personality or the week-by-week shifts of diplomacy and politics; and that power is a relative thing, which can only be described and measured by frequent comparisons between various states and societies.

在定居于欧亚大陆西部的分散的、相对说来缺乏经验的民族中,发生了一场不可阻挡的经济发展和技术创新。这一过程使其在世界事务中稳固地成为商业和军事先驱,这是什么原因呢?这个问题引起学者和其他评论家们的注意已达几个世纪之久。以下段落能做的仅仅是对有关知识作一综述。但不管这个综述是多么粗略,它还是具有揭示渗透全书论据的主要线索的功能,即:有一种主要由经济和技术进步所引起和驱动的机制,虽然这种发展总是同其他可变因素,例如社会结构、地理和偶然事件发生交互作用;要理解世界政治的进程就必须把注意力集中到物质和长期起作用的因素,而不是人物的更换或外交和政治的短期变化;实力是一种相对的事物,只有通过各个国家和社会之间的经常比较才能加以描述和衡量。

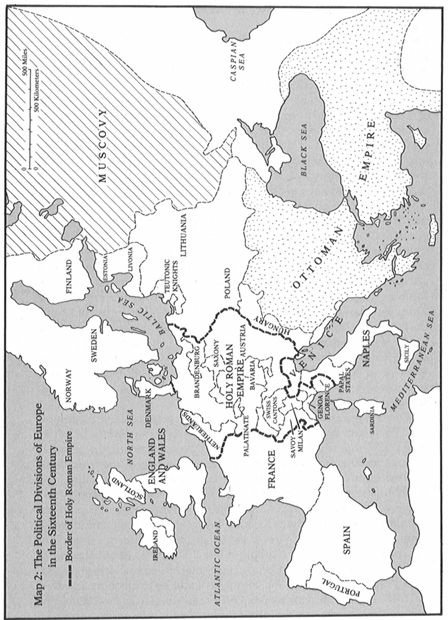

The one feature of Europe which immediately strikes the eye when looking at a map of the world’s “power centers” in the sixteenth century is its political fragmentation (see Maps 1 and 2). This was not an accidental or short-lived state of affairs, such as occurred briefly in China after the collapse of one empire and before its successor dynasty could gather up again the strings of centralized power. Europe had always been politically fragmented, despite even the best efforts of the Romans, who had not managed to conquer much farther north of the Rhine and the Danube; and for a thousand years after the fall of Rome, the basic political power unit had been small and localized, in contrast to the steady expansion of the Christian religion and culture. Occasional concentrations of authority, like that of Charlemagne in the West or of Kievan Russia in the East, were but temporary affairs, terminated by a change of ruler, internal rebellion, or external invasions.

当你观看16世纪世界“实力中心”的地图时,欧洲有一个特征会立刻引起注意,这就是政治上的分裂。这并不是像中国在一个帝国崩溃之后和在其后继王朝得以重新收紧中央集权政权的绳索以前的一个短时期内出现的偶发或短命的事态。欧洲在政治上总是四分五裂,尽管罗马帝国做过最大的努力,他们的征服也未能超过莱茵河和多瑙河以北多少;在罗马陷落后的1000年里,主要政治权力单位同基督教信仰和文化的稳步扩张比较起来,都是既小而又局限在个别地方。像西方查理大帝时期或东方基辅罗斯时期那样政权的偶然集中,只是暂时的事情,会因统治者的更换、国内起义或外部入侵而随即结束。

For this political diversity Europe had largely to thank its geography. There were no enormous plains over which an empire of horsemen could impose its swift dominion; nor were there broad and fertile river zones like those around the Ganges, Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, Yellow, and Yangtze, providing the food for masses of toiling and easily conquerable peasants. Europe’s landscape was much more fractured, with mountain ranges and large forests separating the scattered population centers in the valleys; and its climate altered considerably from north to south and west to east. This had a number of important consequences. For a start, it both made difficult the establishment of unified control, even by a powerful and determined warlord, and minimized the possibility that the continent could be overrun by an external force like the Mongol hordes. Conversely, this variegated landscape encouraged the growth, and the continued existence, of decentralized power, with local kingdoms and marcher lordships and highland clans and lowland town confederations making a political map of Europe drawn at any time after the fall of Rome look like a patchwork quilt. The patterns on that quilt might vary from century to century, but no single color could ever be used to denote a unified empire. 16

欧洲政治上的这种多样性主要是它的地理状况造成的。这里没有骑兵帝国可以把它的快速动力强加其上的大平原;这里也没有像恒河、尼罗河、底格里斯河和幼发拉底河、黄河和长江周围那样广阔而肥沃的流域可以为勤劳而易于征服的农民群众提供粮食。欧洲的地形更为支离破碎,众多的山脉和大森林把分散在各地的人口中心隔离开来;欧洲的气候从北到南和从西到东有很大变化,这导致很多重要后果。首先,它使统一控制变得很困难,甚至强有力的、坚决果断的军阀也难以做到,这就减少了大陆遭受像蒙古游牧部落那样的外部势力蹂躏的可能性。相反,这种多样化的地形促进了分散政权的发展和继续存在,地区王国、边境贵族领地、高地氏族和低地城镇联盟构成了欧洲的政治地图,罗马陷落后任何时期绘制的地图,看起来都像一块用杂色布片补缀起来的被单,这块被单的图案每个世纪都可能不同,但从来没有一种单一的颜色可以用来标明一个统一的帝国。

Europe’s differentiated climate led to differentiated products, suitable for exchange; and in time, as market relations developed, they were transported along the rivers or the pathways which cut through the forests between one area of settlement and the next. Probably the most important characteristic of this commerce was that it consisted primarily of bulk products—timber, grain, wine, wool, herrings, and so on, catering to the rising population of fifteenth-century Europe, rather than the luxuries carried on the oriental caravans. Here again geography played a crucial role, for water transport of these goods was so much more economical and Europe possessed many navigable rivers. Being surrounded by seas was a further incentive to the vital shipbuilding industry, and by the later Middle Ages a flourishing maritime commerce was being carried out between the Baltic, the North Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea. This trade was, predictably, interrupted in part by war and affected by local disasters such as crop failures and plagues; but in general it continued to expand, increasing Europe’s prosperity and enriching its diet, and leading to the creation of new centers of wealth like the Hansa towns or the Italian cities. Regular long-distance exchanges of wares in turn encouraged the growth of bills of exchange, a credit system, and banking on an international scale. The very existence of mercantile credit, and then of bills of insurance, pointed to a basic predictability of economic conditions which private traders had hitherto rarely, if ever, enjoyed anywhere in the world. 17

欧洲不同的气候条件造成了适于交换的不同产品,最后,随着市场关系的发展,这些产品沿着河流或通过林间小道从一个村落区运送到另一个村落区。这种贸易的最主要特点或许是它主要由大宗货物组成——木材、粮食、酒类、羊毛、鲱鱼等等,它们是为了满足欧洲15世纪日益增长的人口的需要,而不是东方商队贸易运输的奢侈品。这里地理又起了关键的作用,因为这些商品用水上运输要经济得多,而欧洲又有许多可通航的河流。周围环海对至关重要的造船工业是又一种刺激,而到中世纪末期时,繁荣的海上贸易就在波罗的海、北海、地中海和黑海之间进行。虽然这种贸易部分地被战争中断,并受局部地区的灾害,例如歉收和瘟疫的影响,但总的说来它还是在继续发展,促进着欧洲的繁荣,丰富其食物并导致建立新的财富中心,如汉莎诸城镇或意大利城邦。定期的远距离商品交易必然会促进国际范围内的汇票、信贷制度和银行业的发展。商业信贷、还有保险单的存在本身就表明经济形势基本上是可预见的,而这以前世界任何地方的私商几乎都没有享有过这种条件。

In addition, because much of this trade was carried through the rougher waters of the North Sea and Bay of Biscay—and also because long-range fishing became an important source of nutrient and wealth—shipwrights were forced to build tough (if rather slow and inelegant) vessels capable of carrying large loads and finding their motive power in the winds alone. Although over time they developed more sail and masts, and stern rudders, and therefore became more maneuverable, North Sea “cogs” and their successors may not have appeared as impressive as the lighter craft which plied the shores of the eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean; but, as we shall see below, they were going to possess distinct advantages in the long run. 18

此外,因为许多贸易都是经过北海和比斯开湾波涛汹涌的海面运输来进行,而且也因为远洋渔业已成为营养和财富的一个重要来源,促使造船工业建造坚固(即使速度还慢,且嫌粗糙)的船舶,以便能运载大量货物并能利用风向航行。虽然在一个时期船只加大了帆、桅杆和尾舵,因而变得更加灵巧,但北海的“小船”和后来取代它们的船舶,可能没有像定期往返于东地中海和印度洋沿岸的轻型船那样给人以深刻印象,但在下面我们将看到,从长远的观点来看,它们将具有特别的优势。

The political and social consequences of this decentralized, largely unsupervised growth of commerce and merchants and ports and markets were of the greatest significance. In the first place, there was no way in which such economic developments could be fully suppressed. This is not to say that the rise of market forces did not disturb many in authority. Feudal lords, suspicious of towns as centers of dissidence and sanctuaries of serfs, often tried to curtail their privileges. As elsewhere, merchants were frequently preyed upon, their goods stolen, their property seized. Papal pronouncements upon usury echo in many ways the Confucian dislike of profit-making middlemen and moneylenders. But the basic fact was that there existed no uniform authority in Europe which could effectively halt this or that commercial development; no central government whose changes in priorities could cause the rise and fall of a particular industry; no systematic and universal plundering of businessmen and entrepreneurs by tax gatherers, which so retarded the economy of Mogul India. To take one specific and obvious instance, it was inconceivable in the fractured political circumstances of Reformation Europe that everyone would acknowledge the pope’s 1494 division of the overseas world into Spanish and Portuguese spheres—and even less conceivable that an order banning overseas trade (akin to those promulgated in Ming China and Tokugawa Japan) would have had any effect.

这种分散的、主要是不受压抑的贸易,以及由商人、港口和市场发展形成的政治和社会后果,具有重大意义。首先,是没有办法完全压制这种经济发展。这并不是说市场势力的兴起没有使许多当权人物担心。封建主们怀疑城市是异端的中心和农奴的避难所,经常试图削减其特权。像其他地方一样,商人常遭抢劫,他们的商品被盗,财产被占。罗马教皇对高利贷的看法,对赢利的中间人和放债人的厌恶,在许多方面与孔子学说发生了共鸣。但基本事实是,在欧洲不存在一个可以有效地阻止这种或那种贸易发展的统一政权;没有一个中央政府由于它改变了发展的进程而造成某一特定工业的兴起或衰落,曾经严重阻碍莫卧儿帝国经济的税收官对商人和企业家进行的全面的掠夺也没有发生。举一个特别明显的例子,在基督教改革时代欧洲政治分裂的环境下,要使每个人都承认教皇1494年把海外世界划分为西班牙和葡萄牙的势力范围,是不可想像的,甚至更难想像禁止海外贸易的命令(如中国明朝和幕府时代的日本所颁布的)会取得什么效果。

The fact was that in Europe there were always some princes and local lords willing to tolerate merchants and their ways even when others plundered and expelled them; and, as the record shows, oppressed Jewish traders, ruined Flemish textile workers, persecuted Huguenots, moved on and took their expertise with them. A Rhineland baron who overtaxed commercial travelers would find that the trade routes had gone elsewhere, and with it his revenues. A monarch who repudiated his debts would have immense difficulties raising a loan when the next war threatened and funds were quickly needed to equip his armies and fleets. Bankers and arms dealers and artisans were essential, not peripheral, members of society. Gradually, unevenly, most of the regimes of Europe entered into a symbiotic relationship with the market economy, providing for it domestic order and a nonarbitrary legal system (even for foreigners), and receiving in taxes a share of the growing profits from trade. Long before Adam Smith had coined the exact words, the rulers of certain societies of western Europe were tacitly recognizing that “little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and tolerable administration of justice. … ”19 From time to time the less percipient leaders—like the Spanish administrators of Castile, or an occasional Bourbon king of France—would virtually kill the goose that laid the golden eggs; but the consequent decline in wealth, and thus in military power, was soon obvious to all but the most purblind.

事实是,即使别人在掠夺和驱逐商人的时候,欧洲总有一些王公和地方贵族愿意容忍商人及其行为方式,而且如文献所载,受压迫的犹太商人、破了产的佛兰芒纺织工人和受迫害的胡格诺教徒,迁移时都随身带着他们的专门技艺。一个莱茵兰的男爵因对商旅过度征税而发现,商路改到别的地方,他的收益不翼而飞了。一位赖债的君主,在面临下一次战争威胁并急需资金去装备他的陆军和舰队时,很难再借到一笔贷款。银行家、军火商人和手工工匠都是社会的重要成员,而不是敲边鼓的。大部分欧洲政权逐渐地、不平衡地与市场经济形成了一种共生的关系,为市场经济提供了国内秩序和非独断专行的法律制度(甚至也对外国人提供),并以税收形式得到日益增长的商业利润的一部分。在亚当·斯密创造出准确词句以前很久,西欧某些社会的统治者就已默认,“为了把一个国家从最低级的野蛮状态发展到最大限度的繁盛,除了和平、轻税和宽容公正的政府以外,就不再需要什么了……”有时那些较少洞察力的领导者,如西班牙卡斯蒂利亚的君主或法国一个偶尔上台的波旁国王,企图杀掉下金蛋的鹅,但结果便是财富减少,以及随之而来的军事实力的衰退。

Probably the only factor which might have led to a centralization of authority would have been such a breakthrough in firearms technology by one state that all opponents were crushed or overawed. In the quickening pace of economic and technical development which occurred in fifteenth-century Europe as the continent’s population recovered from the Black Death and the Italian Renaissance blossomed, this was by no means impossible. It was, as noted above, in this broad period from 1450 to 1600 that “gunpowder empires” were established elsewhere. Muscovy, Tokugawa Japan, and Mogul India provide excellent examples of how great states could be fashioned by leaders who secured the firearms and the cannon with which to compel all rivals to obedience.

可能导致政权中央集权化的唯一因素,是一个国家的火器技术取得非常重大的突破,以致所有敌人都被压垮或慑服。在15世纪欧洲经济和技术发展速度加快的同时,大陆的人口从黑死病的打击下刚刚恢复过来,意大利文艺复兴正在欣欣向荣,这种情况是不可能发生的。如前所述,正是在从1450年至1600年这一相当长的时期内,“火药帝国”在其他地方确立起来。俄罗斯、德川时期的日本和莫卧儿的印度提供了很好的例子,它们说明大国领袖一旦掌握了火器和大炮,就能迫使所有的对手臣服,这样的一些领袖的确能使大国改变形象。

Since, furthermore, it was in late-medieval and early modern Europe that new techniques of warfare occurred more frequently than elsewhere, it was not implausible that one such breakthrough could enable a certain nation to dominate its rivals. Already the signs pointed to an increasing concentration of military power. 20 In Italy the use of companies of crossbowmen, protected when necessary by soldiers using pikes, had brought to a close the age of the knight on horseback and his accompanying ill-trained feudal levy; but it was also clear that only the wealthier states like Venice and Milan could pay for the new armies officered by the famous condottieri. By around 1500, moreover, the kings of France and England had gained an artillery monopoly at home and were thus able, if the need arose, to crush an overmighty subject even if the latter sheltered behind castle walls. But would not this tendency finally lead to a larger transnational monopoly, stretching across Europe? This must have been a question many asked around 1550, as they observed the vast concentration of lands and armies under the Emperor Charles V.

此外,因为新的作战技术较多地发生在中世纪晚期和近代早期的欧洲,而不是在别的地方,一项这样的突破可能帮助某一个国家压倒其竞争对手,这并非难以置信。已有迹象说明军事实力在日益集中。在意大利,使用弩手队(必要时由矛兵保护)结束了骑士以及随其出征的训练不良的封建民兵时代;但同样清楚的是,只有像威尼斯和米兰这样比较富裕的国家才能养得起由有名的雇佣兵队长指挥的新式军队。其次,到大约1500年,法国和英国的国王已经在国内获得大炮垄断权,因而如有必要,能够粉碎特别强大的臣属,即便后者躲到城堡高墙后面也在所难免。但是这种趋势是否最终会导致更大的、横跨欧洲的超国家的垄断呢?这必定是1550年前后许多人提出的一个问题,因为他们当时看到在皇帝查理五世统治下发生了领土和军队的广泛集中。

A fuller discussion of that specific Habsburg attempt, and failure, to gain the mastery of Europe will be presented in the next chapter. But the more general reason why it was impossible to impose unity across the continent can briefly be stated here. Once again, the existence of a variety of economic and military centers of power was fundamental. No one Italian city-state could strive to enhance itself without the others intervening to preserve the equilibrium; no “new monarchy” could increase its dominions without stirring rivals to seek compensation. By the time the Reformation was well and truly under way, religious antagonisms were added to the traditional balance-of-power rivalries, thus making the prospects of political centralization even more remote. Yet the real explanation lies a little deeper; after all, the simple existence of competitors, and of bitter feelings between warring groups, was evident in Japan, India, and elsewhere, but that of itself had not prevented eventual unification. Europe was different in that each of the rival forces was able to gain access to the new military techniques, so that no single power ever possessed the decisive edge. The services of the Swiss and other mercenaries, for example, were on offer to anyone who was able to pay for them. There was no single center for the production of crossbows, nor for that of cannon— whether of the earlier bronze guns or of the later, cheaper cast-iron artillery; instead, such armaments were being made close to the ore deposits on the Weald, in central Europe, in Málaga, in Milan, in Liège, and later in Sweden. Similarly, the proliferation of shipbuilding skills in various ports ranging from the Baltic to the Black Sea made it extremely difficult for any one country to monopolize maritime power, which in turn helped to prevent the conquest and elimination of rival centers of armaments production lying across the sea.

对哈布斯堡称霸欧洲这一特别企图及其失败的详细论述将在下一章进行。但这里将它不可能把统一强加给整个欧洲大陆的较一般性原因,做一简单说明。多个经济和军事实力中心的存在再次成为基本原因。没有一个意大利城邦可以在不受他国为维持均势而进行干预的情况下加强自己;没有一个“新君主政体”可以在不刺激竞争对手寻求补偿的情况下扩大自己的领地。到宗教改革顺利地、确实地进行时,在传统的均势竞争之外又增加了宗教对抗,这就使政治集权的前景变得更加渺茫。然而,真正的解释要深一步,毕竟竞争者和交战集团之间存在着恶感这一简单的事实,在日本、印度和其他地方都能见到,但并没有妨碍最终的统一。欧洲的不同之处在于,每一支竞争力量都可以接触新的军事技术,所以没有一个政权具有决定性的优势。例如,瑞士军队和其他雇佣兵都准备为任何能够付款的人效力。没有独一无二的生产弩机的中心或生产炮的中心,不管是早期的铜炮或晚期较便宜的铸铁炮。这些武器可以在接近森林地带矿床的地方,如中欧、马拉加、米兰、列日,后来在瑞典生产。同样,造船技术在从波罗的海到黑海各个港口的传播,使一个国家极难垄断海上实力,这必然有助于防止征服和消灭坐落在海那边的武器生产竞争中心。

To say that Europe’s decentralized states system was the great obstacle to centralization is not, then, a tautology. Because there existed a number of competing political entities, most of which possessed or were able to buy the military means to preserve their independence, no single one could ever achieve the breakthrough to the mastery of the continent.

那么,如果说欧洲分散的国家体系是集权化的巨大障碍,那就不是同义语的重复了。因为存在着许多竞争的政治实体,它们大多具有或能够购买维护自己独立的军事手段,没有一个国家可以在称霸大陆方面取得突破。

While this competitive interaction between the European states seems to explain the absence of a unified “gunpowder empire” there, it does not at first sight provide the reason for Europe’s steady rise to global leadership. After all, would not the forces possessed by the new monarchies in 1500 have seemed puny if they had been deployed against the enormous armies of the sultan and the massed troops of the Ming Empire? This was true in the early sixteenth century and, in some respects, even in the seventeenth century; but by the latter period the balance of military strength was tilting rapidly in favor of the West. For the explanation of this shift one must again point to the decentralization of power in Europe. What it did, above all else, was to engender a primitive form of arms race among the city-states and then the larger kingdoms. To some extent, this probably had socioeconomic roots. Once the contending armies in Italy no longer consisted of feudal knights and their retainers but of pikemen, crossbowmen, and (flanking) cavalry paid for by the merchants and supervised by the magistrates of a particular city, it was almost inevitable that the latter would demand value for money—despite all the best maneuvers of condottieri not to make themselves redundant; the cities would require, in other words, the sort of arms and tactics which might produce a swift victory, so that the expenses of war could then be reduced. Similarly, once the French monarchs of the late fifteenth century had a “national” army under their direct control and pay, they were anxious to see this force produce decisive results. 21

虽然欧洲国家间这种相互竞争的作用,似乎可以说明缺乏统一的“火药帝国”的原因,但乍看起来不能说明欧洲稳步兴起而占全球领先地位的原因。如果把1500年新君主国家掌握的军队,用来同苏丹的庞大军队和明帝国的众多军队作战,究竟是否会显得太弱了呢?在16世纪早期甚至17世纪,在某些方面是这样的;但在这后一时期,军事实力的均势迅速地朝着有利于西方的方向变化。为解释这种变化,必须再次说明欧洲权力的分散。首先在城邦和随后在较大王国之间进行的原始形式的军备竞赛产生了什么,最重要的是将要产生什么。这或许在某种程度上有社会经济根源。既然意大利交战的军队不再由封建骑士及其侍从组成,而是由商人支付和特定城市的行政长官监督的长矛兵、弩手和(侧翼)骑兵组成,因此该城市会几乎不可避免地要求实现所付金钱的价值,尽管雇佣兵队长们耍尽花招,以免自己成为冗员;换句话说,城市需要能迅速取胜的那种武器和战术,以使军费降下来。同样,既然法国15世纪末期的君主有了一支自己直接控制和支付的“全国性”军队,他们就急于看到这支力量产生决定性的结果。

By the same token, this free-market system not only forced the numerous condottieri to compete for contracts but also encouraged artisans and inventors to improve their wares, so as to obtain new orders. While this armaments spiral could already be seen in the manufacture of crossbows and armor plate in the early fifteenth century, the principle spread to experimentation with gunpowder weapons in the following fifty years. It is important to recall here that when cannon were first employed, there was little difference between the West and Asia in their design and effectiveness. Gigantic wrought-iron tubes that fired a stone ball and made an immense noise obviously looked impressive and at times had results; it was that type which was used by the Turks to bombard the walls of Constantinople in 1453. Yet it seems to have been only in Europe that the impetus existed for constant improvements: in the gunpowder grains, in casting much smaller (yet equally powerful) cannon from bronze and tin alloys, in the shape and texture of the barrel and the missile, in the gun mountings and carriages. All of this enhanced to an enormous degree the power and the mobility of artillery and gave the owner of such weapons the means to reduce the strongest fortresses—as the Italian city-states found to their alarm when a French army equipped with formidable bronze guns invaded Italy in 1494. It was scarcely surprising, therefore, that inventors and men of letters were being urged to design some counter to these cannon (and scarcely less surprising that Leonardo’s notebooks for this time contain sketches for a machine gun, a primitive tank, and a steam-powered cannon). 22

根据同样的理由,这种自由市场制度不仅迫使大量雇佣兵队长为签订合同而进行竞争,也促进手工工匠和发明者改进他们的产品,以争取新的订货。虽然武器的这种螺旋上升在15世纪早期的弩机和盔甲片生产中已经可以见到,但在以后50年该原则又扩大到火药武器的实验。这里回顾一下以下事实是重要的:当最初使用大炮时,西方和亚洲在大炮的设计和效力方面都没有多大差别。发射石球和产生轰然巨响的巨大炮管显然看起来很了不起,并曾起过作用,就是土耳其人曾用于轰击君士坦丁堡城墙的那种炮。然而,似乎只有欧洲才存在不断在技术上进行改进的动力:在火药粒方面,在用铜和锡合金铸造小得多(但火力同样强大)的大炮方面,在炮管和炮弹的形状及结构方面,在炮架和炮车方面。这一切极大地提高了大炮的火力和机动性,给了这种武器的所有者摧毁最坚固堡垒的手段,用强大铜炮装备起来的法军1494年入侵意大利时,意大利城邦惊恐地领教了它们的威力。所以毫不奇怪,发明家和有学问的人都被怂恿去设计某种能抵消这种大炮威力的东西(同样令人惊奇的是,这一时期列奥那多[7]的笔记里就有一种机关枪、原始坦克和蒸汽动力炮的草图)。

This is not to say that other civilizations did not improve their armaments from the early, crude designs; some of them did, usually by copying from European models or persuading European visitors (like the Jesuits in China) to lend their expertise. But because the Ming government had a monopoly of cannon, and the thrusting leaders of Russia, Japan, and Mogul India soon acquired a monopoly, there was much less incentive to improve such weapons once their authority had been established. Turning in upon themselves, the Chinese and the Japanese neglected to develop armaments production. Clinging to their traditional fighting ways, the janissaries of Islam scorned taking much interest in artillery until it was too late to catch up to Europe’s lead. Facing less-advanced peoples, Russian and Mogul army commanders had no compelling need for improved weaponry, since what they already possessed overawed their opponents. Just as in the general economic field, so also in this specific area of military technology, Europe, fueled by a flourishing arms trade, took a decisive lead over the other civilizations and power centers.

这并不是说其他文明没有改进他们早期的、构造简单的武器。它们经常通过模仿欧洲样式或说服欧洲来访者(如在中国的耶稣会会员)出让他们的专长,来进行改进。但因为明朝政府享有大炮的垄断权,而且俄国、日本和莫卧儿印度不久也取得了这种垄断权,既然它们的政权已经确立起来,改进这种垄断权的诱因就要小得多。中国人和日本人转向闭关自守以后,就忽视了发展武器生产。伊斯兰兵因固守传统的作战方式,对大炮的兴趣比较冷淡,直到后来为时已晚,难以赶上欧洲的领先地位。面对不太发达的民族,俄国和莫卧儿军队的指挥官们没有改进武器的迫切需要,因为他们已经拥有压倒敌人的军队。正像在一般经济领域一样,欧洲在军事技术这个特别领域受到繁荣武器贸易的刺激,取得了对其他文明和实力中心的决定性领先地位。

Two further consequences of this armaments spiral need to be mentioned here. One ensured the political plurality of Europe, the other its eventual maritime mastery. The first is a simple enough story and can be dealt with briefly. 23 Within a quarter-century of the French invasion of 1494, and in certain respects even before then, some Italians had discovered that raised earthworks inside the city walls could greatly reduce the effects of artillery bombardment; when crashing into the compacted mounds of earth, cannonballs lost the devastating impact they had upon the outer walls. If these varied earthworks also had a steep ditch in front of them (and, later, a sophisticated series of protected bastions from which muskets and cannon could pour a crossfire), they constituted a near-insuperable obstacle to the besieging infantry. This restored the security of the Italian city-states, or at least of those which had not fallen to a foreign conqueror and which possessed the vast amounts of manpower needed to build and garrison such complex fortifications. It also gave an advantage to the armies engaged in holding off the Turks, as the Christian garrisons in Malta and in northern Hungary soon discovered. Above all, it hindered the easy conquest of rebels and rivals by one overweening power in Europe, as the protracted siege warfare which accompanied the Revolt of the Netherlands attested. Victories attained in the open field by, say, the formidable Spanish infantry could not be made decisive if the foe possessed heavily fortified bases into which he could retreat. The authority acquired through gunpowder by the Tokugawa shogunate, or by Akbar in India, was not replicated in the West, which continued to be characterized by political pluralism and its deadly concomitant, the arms race.

这种武器螺旋上升的两个进一步后果需要在这里提一下,一个后果是确保了欧洲政治的多元化,另一个后果是它最终获得了海上霸权。第一个后果很简单,可以简单叙述。在1494年法国入侵后的1/4世纪以内,甚至在此之前,意大利人就已发现,城墙以内突起的土木工事可以大大地减少大炮轰击的效果;当炮弹射进坚实的土堆时便失去对外墙的那种破坏作用。如果在各种这类土木工事前面再有一条深壕(后来又有一系列构造复杂的设防棱堡,滑膛枪和大炮可以从这里发射交叉火力),它们就会形成围城步兵几乎不可逾越的障碍。这就恢复了意大利城邦的安全,或者至少是那些未落入外国征服者之手的,以及那些拥有建造和守卫这种综合防御体系所需要的人力资源的城邦之安全。这也给了那些参与防御土耳其人的军队一种优越性,如马耳他和匈牙利北部的基督教守卫部队很快发现的那样。首先它阻碍了欧洲一个傲慢强国对叛乱者和竞争者的轻易征服,这就像伴随尼德兰起义的持久包围战所证实的那样。如果敌人有可以退守的坚固设防基地,在开阔战场获得的胜利就不能成为决定性的。德川幕府或印度的阿克巴通过火药所取得的权威,在西方没有被模仿,西方的特点仍旧是政治的多元化及伴随发生的、你死我活的武器竞赛。

The impact of the “gunpowder revolution” at sea was even more wide-ranging. 24 As before, one is struck by the relative similarity of shipbuilding and naval power that existed during the later Middle Ages in northwest Europe, in the Islamic world, and in the Far East. If anything, the great voyages of Cheng Ho and the rapid advance of the Turkish fleets in the Black Sea and eastern Mediterranean might well have suggested to an observer around 1400 and 1450 that the future of maritime development lay with those two powers. There was also little difference, one suspects, between all three regions in regard to cartography, astronomy, and the use of instruments like the compass, astrolabe, and quadrant. What was different was sustained organization. Or, as Professor Jones observes, “given the distances covered by other seafarers, the Polynesians for example, the [Iberian] voyages are less impressive than Europe’s ability to rationalize them and to develop the resources within her reach. ”25 The systematic collection of geographical data by the Portuguese, the repeated willingness of Genoese merchant houses to fund Atlantic ventures which might ultimately compensate for their loss of Black Sea trade, and— farther north—the methodical development of the Newfoundland cod fisheries all signified a sustained readiness to reach outward which was not evident in other societies at that time.

海上“火药革命”的影响甚至更为广泛。以前,北欧、伊斯兰世界和远东在中世纪末期的造船和海军装备上实力相当。如果郑和的远航和土耳其舰队在黑海和东地中海的迅速发展或许对1400年和1450年前后的观察家有什么暗示的话,那就是海运发展的未来在于这两个强国。人们猜测,在有关制图学、天文学以及罗盘、星象仪等仪器的运用这三方面他们很少区别。区别在于持续不变的组织。或者如琼斯教授所说:“假定其他航海家,例如波利尼西亚人都能航行很远的距离,但欧洲在合理地组织航行和在一个航程内开发资源的能力,却比伊比利亚人给人留下更深刻的印象。”葡萄牙人对地理资料进行系统搜集,热那亚商行多次想为大西洋探险提供资金,这种探险最终可能弥补失去黑海贸易的损失,以及再往北依次发展纽芬兰的鳕鱼渔场,这一切都说明一种向外发展的持续意愿,这在这个时期的其他社会是不易见到的。

But perhaps the most important act of “rationalization” was the steady improvement in ships’ armaments. The siting of cannon on sailing vessels was a natural enough development at a time when sea warfare so resembled that on land; just as medieval castles contained archers along the walls and towers in order to drive off a besieging army, so the massive Genoese and Venetian and Aragonese trading vessels used men, armed with crossbows and sited in the fore and aft “castles,” to defend themselves against Muslim pirates in the Mediterranean. This could cause severe losses among galley crews, although not necessarily enough to save a becalmed merchantman if its attackers were really determined.

但是,最重要的“合理化”措施,也许是船上武器装备的不断改善。在海战极力模仿陆战的时代,在帆船上安装大炮是非常自然的发展。正像中世纪的城堡沿城墙和堡垒配置弓箭手以击退包围的军队一样,热那亚、威尼斯和阿拉贡的大商船也以弩机武装起来,守在船头船尾的“堡垒”中,以保卫自己免受地中海穆斯林海盗的侵犯。这会造成船员的严重伤亡,尽管这不一定真能拯救和平的商人,如果进攻者果真下了决心的话。

However, once sailors perceived the advances which had been made in gun design on land— that is, that the newer bronze cannon were much smaller, more powerful, and less dangerous to the gun crew than the enormous wrought-iron bombards—it was predictable that such armaments would be placed on board. After all, catapults, trebuchets, and other sorts of missile-throwing instruments had already been mounted on warships in China and the West. Even when cannon became less volatile and dangerous to their crews, they still posed considerable problems; given the more effective gunpowder, the recoil could be tremendous, sending a gun backward right across the deck if not restrained, and these weapons were still weighty enough to unbalance a vessel if sufficient numbers of them were placed on board (especially on the castles). This was where the stoutly built, rounder-hulled, all-weather three-masted sailing vessel had an inherent advantage over the slim oared galleys of the inland waters of the Mediterranean, Baltic, and Black seas, and over the Arab dhow and even the Chinese junk. It could in any event fire a larger broadside while remaining stable, although of course disasters also occurred from time to time; but once it was realized that the siting of such weapons amidships rather than on the castles provided a much safer gun platform, the potential power of these caravels and galleons was formidable. By comparison, lighter craft suffered from the twin disadvantage of less gun-carrying capacity and greater vulnerability to cannonballs.

然而,一旦水手们领略到陆上大炮设计方面所取得的进步(即,新的铜炮要小得多,威力却要大一些,对炮手的危险要比笨重的锻铁炮小),就会很快将这种武器装在船上,尽管中国和西方的军舰上已经装上了石弩、投石机和其他类型的投掷器械。即使大炮已变得不那么容易爆炸,对船员已不那么危险,它们仍然存在很大的问题:假如使用威力较大的火药,后坐力就会很大,如果大炮未加固定,就会被反作用力弹回甲板,而且这种武器仍然很重,如果船舷上(特别是在炮台上)装的炮很多,足可使船失去平衡。这时,欧洲坚固的、船壳略呈圆形的三桅全天候帆船所固有的优越性显示出来,它们使在地中海、波罗的海和黑海等内海航行的窄条划桨单层平底帆船、阿拉伯人的独桅三角帆船、甚至中国人的平底帆船都相形见绌。它们可以在任何情况下用更大的舷炮开火,而使船保持稳定,当然事故还是不时发生;但人们很快认识到,把这种武器安置在船舰中部而不是炮台上,可以提供安全得多的炮床时,这种轻快帆船和大帆船的潜在威力就变得很强大。相形之下,轻便小船受到双重劣势的不利影响,携带炮火的能力小,更容易受到炮弹的损伤。

One is obliged to stress the words “potential power” because the evolution of the gunned long-range sailing ship was a slow, often uneven development. Many hybrid types were constructed, some carrying multiple masts, guns, and rows of oars. Galley-type vessels were still to be seen in the English Channel in the sixteenth century. Moreover, there were considerable arguments in favor of continuing to deploy galleys in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea; they were swifter on many occasions, more maneuverable in inshore waters, and thus easier to use in conjunction with land operations along the coast—which, for the Turks, outweighed the disadvantages of their being short-ranged and unable to act in heavy seas. 26

有必要强调“潜在威力”一词,因为带炮远洋帆船的演进是一种缓慢而不平衡的发展。建造过许多混合型的舰船,有些装有多根桅杆、多门大炮和多排的桨。16世纪在英吉利海峡仍能见到单层平底大帆船型的船只,此外,有大量证据说明,在地中海和黑海也在继续使用这种船。在很多情况下这种船航速较快,在近海操作比较灵便,因而比较容易用来与沿海陆地运输相衔接,对土耳其人来说,这些船要优于那些只能作短程航行而不能远海航行的船。

In just the same way, we should not imagine that as soon as the first Portuguese vessels rounded the Cape of Good Hope, the age of unchallenged western dominance had begun. What historians refer to as the “Vasco da Gama epoch” and the “Columbian era”—that is, the three or four centuries of European hegemony after 1500—was a very gradual process. Portuguese explorers might have reached the shores of India by the 1490s, but their vessels were still small (often only 300 tons) and not all that well armed—certainly not compared with the powerful Dutch East Indiamen which sailed in those waters a century later. In fact, the Portuguese could not penetrate the Red Sea for a long while, and then only precariously, nor could they gain much of a footing in China; and in the late sixteenth century they lost some of their East African stations to an Arab counteroffensive. 27

同样,我们不能设想,第一批葡萄牙船一绕过好望角就立即开始了没有争议的西方制海权时代。历史学家提到的“瓦斯科·达·伽马时代”和“哥伦布时代”(即1500年以后300年或400年的欧洲霸权),是一个非常缓慢的过程。葡萄牙探险家在15世纪90年代以前或许已经抵达印度海岸,但他们的船舶仍然很少(经常只有300吨),而且并非所有船都配有很好的武器装备,当然不能同一个世纪后航行于这些水域的强大的荷兰东印度公司的商船相比。事实上葡萄牙人不能长期渗入红海,也不能频繁涉足中国,只是偶尔到过那里;而在16世纪末期,他们的一些东非停靠站就在一次阿拉伯的反攻中失落了。

It would be erroneous, too, to assume that the non-European powers simply collapsed like a pack of cards at the first signs of western expansionism. This was precisely what did happen in Mexico, Peru, and other less developed societies of the New World when the Spanish adventurers landed. Elsewhere, the story was very different. Since the Chinese government had voluntarily turned its back upon maritime trade, it did not really care if that commerce fell into the hands of the barbarians; even the quasi-official trading post which the Portuguese set up at Macao in 1557, lucrative though it must have been to the local silk merchants and conniving administrators, does not seem to have disturbed Peking’s equanimity. The Japanese, for their part, were much more blunt. When the Portuguese sent a mission in 1640 to protest against the expulsion of foreigners, almost all its members were killed; there could be no attempt at retribution from Lisbon. Finally, Ottoman sea power was holding its own in the eastern Mediterranean, and Ottoman land power remained a massive threat to central Europe. In the sixteenth century, indeed, “to most European statesmen the loss of Hungary was of far greater import than the establishment of factories in the Orient, and the threat to Vienna more significant than their own challenges at Aden, Goa and Malacca; only governments bordering the Atlantic could, like their later historians, ignore this fact. ”28

如果设想非欧洲的强国一见到西方的扩张主义就像一沓纸牌一样倒塌了,那也是错误的。墨西哥、秘鲁和新世界其他不太发达的社会在西班牙探险家登陆时,的确发生过这种情况。既然中国政府曾自动地忽视海上贸易,如果商业落入蛮人之手,它不会真正关心;甚至葡萄牙人1557年在厦门建立半官方商站,似乎也没有搅扰北京的平静,虽然这个商站对地方丝商和纵容它的行政官员们必定有利可图。日本人方面要率直得多。当葡萄牙人1640年派遣一个使团去日本抗议其驱逐外国人时,几乎所有团员都被杀害;里斯本却无法对其进行惩罚。最后,奥斯曼的海军实力坚守着东地中海,而奥斯曼的陆军实力仍然对中欧构成重大威胁。实际上,在16世纪,“对大多数欧洲政治家来说,丢失匈牙利比在东方建立工厂的重要性要大得多,而对维也纳的威胁要比他们自己在亚丁、果阿和马六甲进行的挑衅重要得多;只有那些濒临大西洋的政府像它们后来的历史学家一样,可以忽视这一事实”。

Yet when all these reservations are made, there is no doubt that the development of the long-range armed sailing ship heralded a fundamental advance in Europe’s place in the world. With these vessels, the naval powers of the West were in a position to control the oceanic trade routes and to overawe all societies vulnerable to the workings of sea power. Even the first great clashes between the Portuguese and their Muslim foes in the Indian Ocean made this clear. No doubt they exaggerated in retrospect, but to read the journals and reports of da Gama and Albuquerque, describing how their warships blasted their way through the massed fleets of Arab dhows and other light craft which they encountered off the Malabar coast and in the Ormuz and Malacca roads, is to gain the impression that an extraterrestrial, superhuman force had descended upon their unfortunate opponents. Following the new tactic that “they were by no means to board, but to fight with the artillery,” the Portuguese crews were virtually invincible at sea. 29 On land it was quite a different matter, as the fierce battles (and occasional defeats) at Aden, Jiddah, Goa, and elsewhere demonstrated; yet so determined and brutal were these western invaders that by the mid-sixteenth century they had carved out for themselves a chain of forts from the Gulf of Guinea to the South China Sea. Although never able to monopolize the spice trade from the Indies—much of which continued to flow via the traditional channels to Venice—the Portuguese certainly cornered considerable portions of that commerce and profited greatly from their early lead in the race for empire. 30

无疑,远距离武装帆船的发展预示了欧洲在世界上地位的重要推进。西方海军强国利用这些舰船使自己处于一种非常有利的地位:控制大西洋商路,慑服所有容易受到海上实力攻击的社会。葡萄牙人同他们的穆斯林敌人在印度洋上的头几次重大冲突,就使这一点清楚无疑。达·伽马和阿布奎基在他们的航海日志和报告中,描述了他们的战舰如何冲杀和摧毁在马拉巴尔海岸附近、霍尔木兹海峡和马六甲路上遇到的由阿拉伯独桅三角帆船和其他轻型船组成的庞大舰队,为自己开辟道路。无疑,他们在回忆中有所夸大,但读这些航海日志和报告可以得到这样一种印象,似乎一种天外超人的力量突然袭击了它们不幸的敌人。葡萄牙船员遵循新的战术,即“他们决不能登船,只能同大炮战斗”,他们在海上实际上是不可战胜的。在陆上,如在亚丁、吉达、果阿和其他地方进行的激烈战斗(并偶尔战败)所表明的,情况全然不同。然而,这些西方入侵者的决心如此之大,又如此残忍,到16世纪中叶,他们已经为自己开辟了从几内亚湾到南中国海的一系列要塞。虽然葡萄牙人从未能垄断印度的香料贸易(其中很大一部分继续经传统渠道运到威尼斯),但他们也操纵了这种贸易的相当大一部分,并从他们争夺帝国的早期领先地位中得到很大好处。

The evidence of profit was even greater, of course, in the vast land empire which the conquistadores swiftly established in the western hemisphere. From the early settlements in Hispaniola and Cuba, Spanish expeditions pushed toward the mainland, conquering Mexico in the 1520s and Peru in the 1530s. Within a few decades this dominion extended from the River Plate in the south to the Rio Grande in the north. Spanish galleons, plying along the western coast, linked up with vessels coming from the Philippines, bearing Chinese silks in exchange for Peruvian silver. In their “New World” the Spaniards made it clear that they were there to stay, setting up an imperial administration, building churches, and engaging in ranching and mining. Exploiting the natural resources—and, still more, the native labor—of these territories, the conquerors sent home a steady flow of sugar, cochineal, hides, and other wares. Above all, they sent home silver from the Potosí mine, which for over a century was the biggest single deposit of that metal in the world. All this led to “a lightning growth of transatlantic trade, the volume increasing eightfold between 1510 and 1550, and threefold again between 1550 and 1610. ”31

当然,征服者在西半球迅速建立的广大陆上帝国内获利的证据更多。西班牙远征军从伊斯帕尼奥拉和古巴的早期居留地出发,向大陆推进,于16世纪20年代征服墨西哥,30年代征服秘鲁。在几十年内,这块领地从南部的拉普拉塔河扩展到北部的里奥格兰德。西班牙大帆船沿着西海岸定期往返,与来自菲律宾群岛的船相衔接,后者载来中国丝绸以交换秘鲁的白银。在“新世界”,西班牙人建立帝国行政机构、建筑教堂并经营牧场和矿山,明确表示要在那里待下去。征服者通过开发这些领土上的自然资源,而且更多的是利用土著劳动力,把源源不断的糖、胭脂红、皮革和其他商品运送回国。最重要的是把波多西矿中的白银运送回国,该矿在100多年的时间里是世界上最大的单一银矿。这一切导致“跨越大西洋贸易的飞速增长,其贸易额在1510年和1550年之间增长了7倍,而在1550年和1610年之间又增长了2倍”。

All the signs were, therefore, that this imperialism was intended to be permanent. Unlike the fleeting visits paid by Cheng Ho, the actions of the Portuguese and Spanish explorers symbolized a commitment to alter the world’s political and economic balances. With their ship-borne cannon and musket-bearing soldier, they did precisely that. In retrospect it sometimes seems difficult to grasp that a country with the limited population and resources of Portugal could reach so far and acquire so much. In the special circumstances of European military and naval superiority described above, this was by no means impossible. Once it was done, the evident profits of empire, and the desire for more, simply accelerated the process of aggrandizement.

因此,所有迹象表明,这个帝国主义企图永远待下去。葡萄牙和西班牙探险家的行动与郑和的短暂访问不同,他们象征着承担改变该大陆政治和经济平衡的使命。他们用舰载大炮和带滑膛枪的士兵所作的正是这件事。回顾历史时,有时似乎很难理解:一个像葡萄牙这样人口和资源都很有限的国家,怎么能航行如此之远并取得如此之多。在上述欧洲陆军和海军优势的特殊情况下,这绝非不可能。这一步一经迈出,帝国的丰厚利润以及获取更多利润的愿望更加快了扩张的过程。

There are elements in this story of “the expansion of Europe” which have been ignored, or but briefly mentioned so far. The personal aspect has not been examined, and yet—as in all great endeavors—it was there in abundance: in the encouragements of men like Henry the Navigator; in the ingenuity of ship craftsmen and armorers and men of letters; in the enterprise of merchants; above all, in the sheer courage of those who partook in the overseas voyages and endured all that the mighty seas, hostile climates, wild landscapes, and fierce opponents could place in their way. For a complex mixture of motives—personal gain, national glory, religious zeal, perhaps a sense of adventure—men were willing to risk everything, as indeed they did in many cases. Nor has there been much dwelling upon the awful cruelties inflicted by these European conquerors upon their many victims in Africa, Asia, and America. If these features are hardly mentioned here, it is because many societies in their time have thrown up individuals and groups willing to dare all and do anything in order to make the world their oyster. What distinguished the captains, crews, and explorers of Europe was that they possessed the ships and the firepower with which to achieve their ambitions, and that they came from a political environment in which competition, risk, and entrepreneurship were prevalent.

“欧洲扩张”史中有些因素以前被忽略了,或仅简单提到。没有对个人作用方面进行考查,然而(如在一切重要努力中)这方面的内容是很丰富的:亨利(航海家)等人的鼓励;造船工匠、武器制造者和学者们的天才;商人的进取精神;最重要的是那些参与远航,沿途经受浩瀚大海、恶劣气候、荒凉地形和残暴敌人可能造成的种种艰难困苦的绝对勇气。由于个人得失、国家荣誉、宗教狂热,或许还有冒险意识等各种动机的结合,人们甘冒一切风险,在许多情况下他们的确冒了风险。对于欧洲征服者强加给他们在非洲、亚洲和美洲的牺牲者的可怕残忍,一般很少叙及。如果说这些特点很少提及的话,是因为那时的许多社会都把这样一些个人和集团推上前台:他们为把世界变成自己的囊中物而敢冒一切风险并愿做任何事情。欧洲的船长、船员和探险家们最杰出的地方在于,他们拥有可以用来实现其野心的船舶和火力,他们来自笼罩着竞争、冒险和企业家精神的一种政治环境。

The benefits accruing from the expansion of Europe were widespread and permanent, and—most important of all—they helped to accelerate an alreadyexisting dynamic. The emphasis upon the acquisition of gold, silver, precious metals, and spices, important though such valuables were, ought not to obscure the worth of the less glamorous items which flooded into Europe’s ports once its sailors had breached the oceanic frontier. Access to the Newfoundland fisheries brought an apparently inexhaustible supply of food, and the Atlantic Ocean also provided the whale oil and seal oil vital for illumination, lubrication, and many other purposes. Sugar, indigo, tobacco, rice, furs, timber, and new plants like the potato and maize were all to boost the total wealth and well-being of the continent; later on, of course, there was to come the flow of grain and meats and cotton. But one does not need to anticipate the cosmopolitan world economy of the later nineteenth century to understand that the Portuguese and Spanish discoveries were, within decades, of great and ever-growing importance in enhancing the prosperity and power of the western portions of the continent. Bulk trades like the fisheries employed a large number of hands, both in catching and in distribution, which further boosted the market economy. And all of this gave the greatest stimulus to the European shipbuilding industry, attracting around the ports of London, Bristol, Antwerp, Amsterdam, and many others a vast array of craftsmen, suppliers, dealers, insurers. The net effect was to give to a considerable proportion of western Europe’s population—and not just to the elite few—an abiding material interest in the fruits of overseas trade.

欧洲扩张的好处是广泛而持久的,而最重要的是它们有助于促进已经存在的机制。虽然重点在于获取金、银等贵金属和香料,但不管这些贵重物品多么重要,也不能忽视欧洲海员横跨大西洋以后大量涌进欧洲港口的次要商品的价值。进入纽芬兰渔场带来了用之不竭的食物供应,而且大西洋还提供了照明、润滑和其他用途迫切需要的鲸鱼油和海豹油。糖、靛蓝、烟草、大米、毛皮、木材和像土豆、玉米那样的新植物,都增加了欧洲大陆总的财富和福利,当然,后来还有源源不断的粮食、肉和棉花到来。但要理解葡萄牙人和西班牙人的发现在几十年内对增强大陆西部的繁荣和实力的巨大的、日益增加的重要性,人们无需过早谈论后来19世纪的全球性世界经济。像渔业这种大宗贸易在捕鱼和销售方面都需要雇佣大量人手,这进一步促进了市场经济。而这一切对欧洲造船工业造成了最大的刺激,把大量手工工匠、供应厂商、商人和承保人等都吸引到伦敦、布里斯托尔、安特卫普、阿姆斯特丹及其他许多港口周围。其直接效果是使很大一部分西欧居民、而不仅是少数上层代表人物,对海外贸易成果发生了一种持续的物质兴趣。

When one adds to this list of commodities the commerce which attended the landward expansion of Russia—the furs, hides, wood, hemp, salt, and grain which came from there to western Europe—then scholars have some cause in describing this as the beginnings of a “modern world system. ”32 What had started as a number of separate expansions was steadily turning into an interlocking whole: the gold of the Guinea coast and the silver of Peru were used by the Portuguese, Spaniards, and Italians to pay for spices and silks from the Orient; the firs and timber of Russia helped in the purchase of iron guns from England; grain from the Baltic passed through Amsterdam on its way to the Mediterranean. All this generated a continual interaction—of further European expansion, bringing fresh discoveries and thus trade opportunities, resulting in additional gains, which stimulated still more expansion. This was not necessarily a smooth upward progression: a great war in Europe or civil unrest could sharply reduce activities overseas. But the colonizing powers rarely if ever gave up their acquisitions, and within a short while a fresh wave of expansion and exploration would begin. After all, if the established imperial nations did not exploit their positions, others were willing to do it instead.

如果在这一个商品单子上再加上俄国向大陆发展的贸易,即从俄国运到西欧的毛皮、皮革、木材、麻、盐和粮食,那么学者就有理由把这描绘为一种“现代世界体系”的发端。开始时是许多单独的扩张,它们确定不移地汇合为一个连锁体:几内亚沿岸的黄金和秘鲁的白银被葡萄牙人、西班牙人和意大利人用于支付从东方来的香料和丝绸;俄国的冷杉和木材帮助它从英国采购铁炮;粮食从波罗的海途经阿姆斯特丹运到地中海。这一切造成一种持续的相互作用——欧洲的进一步扩张,带来新的发现,因而带来贸易机会,结果是额外的收获,这又刺激了更大的扩张。这不一定就是一帆风顺的,欧洲的大战或内乱会急剧减少海外活动。但殖民强国几乎从不放弃自己的囊中物,而且在短期内新的扩张浪潮和探险又会开始。如果已经确立起来的帝国主义国家没有开发它们占有的阵地,毕竟还有别的国家想取而代之。

This, finally, was the greatest reason why the dynamic continued to operate as it did: the manifold rivalries of the European states, already acute, were spilling over into transoceanic spheres. Try as they might, Spain and Portugal simply could not keep their papally assigned monopoly of the outside world to themselves, the more especially when men realized that there was no northeast or northwest passage from Europe to Cathay. Already by the 1560s, Dutch, French, and English vessels were venturing across the Atlantic, and a little later into the Indian and Pacific oceans—a process quickened by the decline of the English cloth trade and the Revolt of the Netherlands. With royal and aristocratic patrons, with funding from the great merchants of Amsterdam and London, and with all the religious and nationalist zeal which the Reformation and Counter-Reformation had produced, new trading and plundering expeditions set out from northwest Europe to secure a share of the spoils. There was the prospect of gaining glory and riches, of striking at a rival and boosting the resources of one’s own country, and of converting new souls to the one true faith; what possible counterarguments could hold out against the launching of such ventures?33

最后,这是为什么这个机制如同以前一样继续起作用的最大原因:欧洲国家已经很尖锐的多重竞争,更发展到大洋彼岸的领域。西班牙和葡萄牙人虽曾极力保住罗马教皇分配给它们的对外部世界的垄断地位,但它们简直就不可能保住,特别是当人们认识到并不存在从欧洲通向中国的东北通道或西北通道以后。还在1560年以前,荷兰人、法国人和英国人的船只已冒险穿越大西洋,稍后进入印度洋和太平洋,英国呢绒业的衰落和尼德兰起义加快了这一过程。在国王和贵族的庇护下,在阿姆斯特丹和伦敦大商人的资助下,以及在宗教改革和反宗教改革造成的一切宗教和民族主义狂热的推动下,新的商业和掠夺性远征从西北欧出发,以获取一份赃物。既然有获得荣耀和财富、打击竞争者和增进本国资源,以及把新的精神变成真诚信仰的前景,还可能有什么相反的论据提出来反对进行这种冒险呢?

The fairer aspect of this increasing commercial and colonial rivalry was the parallel upward spiral in knowledge—in science and technology. 34 No doubt many of the advances of this time were spinoffs from the arms race and the scramble for overseas trade; but the eventual benefits transcended their inglorious origins. Improved cartography, navigational tables, new instruments like the telescope, barometer, backstaff, and gimbaled compass, and better methods of shipbuilding helped to make maritime travel a less unpredictable form of travel. New crops and plants not only brought better nutrition but also were a stimulus to botany and agricultural science. Metallurgical skills, and indeed the whole iron industry, made rapid progress; deep-mining techniques did the same. Astronomy, medicine, physics, and engineering also benefited from the quickening economic pace and the enhanced value of science. The inquiring, rationalist mind was observing more, and experimenting more; and the printing presses, apart from producing vernacular Bibles and political treatises, were spreading these findings. The cumulative effect of this explosion of knowledge was to buttress Europe’s technological—and therefore military—superiority still further. Even the powerful Ottomans, or at least their frontline soldiers and sailors, were feeling some of the consequences of this by the end of the sixteenth century. On other, less active societies, the effects were to be far more serious. Whether or not certain states in Asia would have taken off into a self-driven commercial and industrial revolution had they been left undisturbed seems open to considerable doubt;35 but what was clear was that it was going to be extremely difficult for other societies to ascend the ladder of world power when the more advanced European states occupied all the top rungs.

This difficulty would be compounded, it seems fair to argue, because moving up that ladder would have involved not merely the acquisition of European equipment or even of European techniques: it would also have implied a wholesale borrowing of those general features which distinguished the societies of the West from all the others. It would have meant the existence of a market economy, if not to the extent proposed by Adam Smith then at least to the extent that merchants and entrepreneurs would not be consistently deterred, obstructed, and preyed upon. It would also have meant the existence of a plurality of power centers, each if possible with its own economic base, so that there was no prospect of the imposed centralization of a despotic oriental-style regime—and every prospect of the progressive, if turbulent and occasionally brutal, stimulus of competition. By extension, this lack of economic and political rigidity would imply a similar lack of cultural and ideological orthodoxy—that is, a freedom to inquire, to dispute, to experiment, a belief in the possibilities of improvement, a concern for the practical rather than the abstract, a rationalism which defied mandarin codes, religious dogma, and traditional folklore. 36 In most cases, what was involved was not so much positive elements, but rather the reduction in the number of hindrances which checked economic growth and political diversity. Europe’s greatest advantage was that it had fewer dis advantages than the other civilizations.

似乎可以这样说,这种困难是多方面的,因为向上攀登阶梯不仅需要获取欧洲的装备甚至欧洲的技术,而且要全面借鉴使西方社会不同于其他一切社会的那些一般特征。这意味着有一种市场经济,即便不是亚当·斯密提出的那种程度的市场经济,至少商人和企业家不会经常受到威慑、阻挠和掠夺。这同样意味着要有一种权力中心的多元化,每个中心都应尽可能有自己的经济基础,以免出现一种强加的东方式专制制度的集权化前景,而创造出进步的刺激竞争的一切可能前景,尽管会有骚动,偶尔伴有残忍。推而广之,这种削弱经济和政治的僵化会意味着同样削弱文化和思想的正统观念,这是一种探索、争论和实验的自由,是信仰改进的可能性,是关心实际而不是抽象的事物,是一种蔑视达官贵人的信条、宗教教条和传统民俗的理性主义。在多数情况下并不牵扯许多积极因素,而是阻碍经济增长和政治多样化障碍的减少。欧洲的最大优势是它较少被其他文化所羁绊。

Although it is impossible to prove it, one suspects that these various general features related to one another, by some inner logic as it were, and that all were necessary. It was a combination of economic laissez-faire, political and military pluralism, and intellectual liberty—however rudimentary each factor was compared with later ages—which had been in constant interaction to produce the “European miracle. ” Since the miracle was historically unique, it seems plausible to assume that only a replication of all its component parts could have produced a similar result elsewhere. Because that mix of critical ingredients did not exist in Ming China, or in the Muslim empires of the Middle East and Asia, or in any other of the societies examined above, they appeared to stand still while Europe advanced to the center of the world stage.

虽然不可能对此加以证明,人们会猜想,根据它固有的某种内部逻辑,这种种一般特征是相互关联的,而且都是必然的。欧洲的优势是经济自由放任、政治和军事的多元化以及智力活动自由的一种结合,这些因素在经常的相互作用中产生了“欧洲的奇迹”。因为这种奇迹在历史上是独特的,似乎可以合理地假定,只要模仿其全部组成部分,就可以在别的地方产生同样的结果。因为在明代中国、中东和亚洲的穆斯林帝国或上面考查过的任何其他社会都不存在这种关键成分的融合,于是,当欧洲已发展为世界舞台的中心时,它们却似乎仍停滞不前。

* For a brief while, in the 1590s, a somewhat revived Chinese coastal fleet helped the Koreans to resist two Japanese invasion attempts; but even this rump of the Ming navy declined thereafter.

【注】

[1]指穆罕默德。——译者

[2]休达,在摩洛哥最北端,即直布罗陀海峡东南的一个港口,属西班牙。——审校者注

[3] 在16世纪90年代的一个短暂时期,有所恢复的中国沿海舰队曾协助高丽人抵御了日本人两次入侵的尝试。但即使明朝海军的这部分残余力量随后也衰落了。

[4]1066年10月14日,诺曼底公爵威廉(征服者)在英国哈斯丁斯登陆,后自立为英国国王。

[5]马修·加尔布雷斯·培里(1794—1858),美国海军准将,1853年率舰队到达日本。1854年2月又率一支舰队到日本神奈川,强迫日本签订《日美和好条约》。

[6]普雷斯特·约翰,传说中的一位基督教徒国王和牧师,据说曾统治远东或非洲的某一王国。——审校者注

[7]列奥那多·达·芬奇(1452-1519),意大利美术家、自然科学家、工程师和哲学家。——审校者注