The Meaning and Chronology of the Struggle

一 角逐的目标与纪年

Although there were always specific reasons why any particular state was drawn into this larger context, two more general causes were chiefly responsible for the transformation in both the intensity and geographical scope of European warfare. The first of these was the coming of the Reformation—sparked off by Martin Luther’s personal revolt against papal indulgences in 1517—which swiftly added a fierce new dimension to the traditional dynastic rivalries of the continent. For particular socioeconomic reasons, the advent of the Protestant Reformation—and its response, in the form of the Catholic Counter-Reformation against heresy—also tended to divide the southern half of Europe from the north, and the rising, citybased middle classes from the feudal orders, although there were, of course, many exceptions to such general alignments. 2 But the basic point was that “Christendom” had fractured, and that the continent now contained large numbers of individuals drawn into a transnational struggle over religious doctrine. Only in the midseventeenth century, when men recoiled at the excesses and futility of religious wars, would there arrive a general, if grudging, acknowledgment of the confessional division of Europe.

虽然任何卷入这场大规模斗争的国家都各有其特殊原因,但造成欧洲战争升级和扩大范围的普遍原因有二。其一,是宗教改革,导火线是1517年马丁·路德对教皇专权的反抗。这为传统的王朝斗争增加了凶险的新内容。由于特定的社会经济原因,宗教改革以及它的对立面,即天主教对异教运动的反改革,都倾向于将欧洲南半部与北半部分开,把新兴的、以城市为基础的中产阶级与封建贵族分开。在这一大分化及归类中,当然会有不少例外情况。但基本的一点是,基督教社会分裂了,欧洲大陆有许多人被拉入了为教义而进行的超国界的斗争。直到17世纪中叶,当宗教战争的过火行为和徒劳无益使人们消极退缩下来时,他们才普遍地或许亦是勉强地承认对欧洲教派的分裂。

The second reason for the much more widespread and interlinked pattern of warfare after 1500 was the creation of a dynastic combination, that of the Habsburgs, to form a network of territories which stretched from Gibraltar to Hungary and from Sicily to Amsterdam, exceeding in size anything which had been seen in Europe since the time of Charlemagne seven hundred years earlier. Stemming originally from Austria, Habsburg rulers had managed to get themselves regularly elected to the position of Holy Roman emperor—a title much diminished in real power since the high Middle Ages but still sought after by princes eager to play a larger role in German and general European affairs.

使得1500年以后的战争更为广泛和复杂的第二个原因,是哈布斯堡家族的王朝联合体。该联合体的领土,从直布罗陀到匈牙利,从西西里到阿姆斯特丹,形成一个网络。欧洲自700年前查理大帝时代以后,再没有过如此庞大的家族王朝。哈布斯堡王室家族起源于奥地利,这些统治者不断地想方设法当选为神圣罗马帝国的皇帝。虽然中世纪盛世以来,此一头衔已大失实权,但仍有不少王公孜孜以求,以便在德国乃至整个欧洲发挥更大作用。

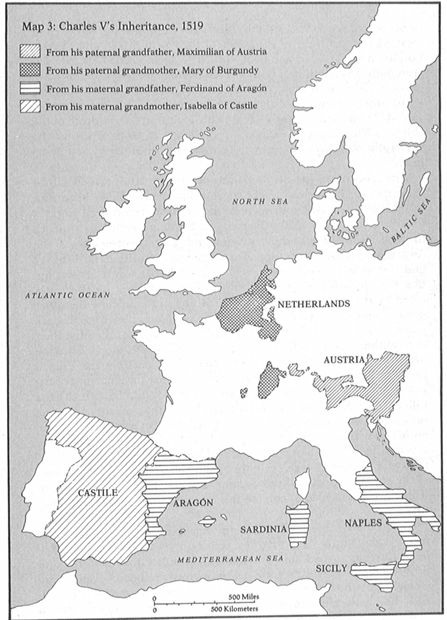

More practically, the Habsburgs were without equal in augmenting their territories through marriage and inheritance. One such move, by Maximilian I of Austria (1493–1519, and Holy Roman emperor 1508–1519), had brought in the rich hereditary lands of Burgundy and, with them, the Netherlands in 1477. Another, consequent upon a marriage compact of 1515, was to add the important territories of Hungary and Bohemia; although the former was not within the Holy Roman Empire and possessed many liberties, this gave the Habsburgs a great bloc of lands across central Europe. But the most far-reaching of Maximilian’s dynastic link-ups was the marriage of his son Philip to Joan, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, whose own earlier union had brought together the possessions of Castile and Aragon (which included Naples and Sicily). The “residuary legatee”3 to all these marriage compacts was Charles, the eldest son of Philip and Joan. Born in 1500, he became Duke of Burgundy at the age of fifteen and Charles I of Spain a year later, and then—in 1519—he succeeded his paternal grandfather Maximilian I both as Holy Roman emperor and as ruler of the hereditary Habsburg lands in Austria. As the Emperor Charles V, therefore, he embodied all four inheritances until his abdications of 1555–1556 (see Map 3). Only a few years later, in 1526, the death of the childless King Louis of Hungary in the battle of Mohacs against the Turks allowed Charles to claim the crowns of both Hungary and Bohemia.

实际上,哈布斯堡家族是通过婚姻和继承权来扩大领土的,这种做法举世无双。一个例证是,奥地利的马克西米利安一世(1493—1519年任神圣罗马帝国皇帝),在1477年通过这种做法一举获取勃艮第的富饶土地遗产,另取得尼德兰。另一例证是,在1515年通过一纸婚约,取得匈牙利和波希米亚。虽然前者不在神圣罗马帝国疆域内,且拥有相当多的自由权,但哈布斯堡王朝因之获得横跨中欧的大片土地。马克西米利安影响最为深远的王朝联姻,是其子费利普娶西班牙国王之女胡安娜,而胡安娜的父母斐迪南和伊莎贝拉已通过自己的联姻把卡斯提尔和阿拉贡的领地(包括那不勒斯和西西里)联为一体,这些婚姻的“遗产继承人”是查理,即费利普和胡安娜的长子。他生于1500年,15岁时成为勃艮第大公;一年后成为西班牙国王查理一世;1519年,更继承祖父马克西米利安一世的大业,成为神圣罗马帝国皇帝和哈布斯堡家族在奥地利世袭领地的统治者。因此,他作为皇帝查理五世,到1555—1556年间退位时止,一直领有全部四份世袭领地(见地图3)。1526年,无嗣的匈牙利国王路易在与土耳其人进行的摩哈赤之役中阵亡,查理又戴上了匈牙利和波希米亚的王冠。

The sheer heterogeneity and diffusion of these lands, which will be examined further below, might suggest that the Habsburg imperium could never be a real equivalent to the uniform, centralized empires of Asia. Even in the 1520s, Charles was handing over to his younger brother Ferdinand the administration and princely sovereignty of the Austrian hereditary lands, and also of the new acquisitions of Hungary and Bohemia—a recognition, well before Charles’s own abdication, that the Spanish and Austrian inheritances could not be effectively ruled by the same person. Nonetheless, that was not how the other princes and states viewed this mighty agglomeration of Habsburg power. To the Valois kings of France, fresh from consolidating their own authority internally and eager to expand into the rich Italian peninsula, Charles V’s possessions seemed to encircle the French state—and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that the chief aim of the French in Europe over the next two centuries would be to break the influence of the Habsburgs. Similarly, the German princes and electors, who had long struggled against the emperor’s having any real authority within Germany itself, could not but be alarmed when they saw Charles V’s position was buttressed by so many additional territories, which might now give him the resources to impose his will. Many of the popes, too, disliked this accumulation of Habsburg power, even if it was often needed to combat the Turks, the Lutherans, and other foes.

这些领地的多样性及其分散状况将在下面具体讨论。哈布斯堡主权的状况使人联想到它绝不是亚洲式的真正统一的中央集权帝国。甚至在16世纪20年代,查理就已把奥地利的世袭地产和刚得到的匈牙利及波希米亚行政管理权——亲王主权交给了他弟弟斐迪南。也就是说,早在查理退位之前,他已承认,西班牙和奥地利的世袭领地不可能由一个人有效地统治。尽管如此,其他王公和国家并不这样看待哈布斯堡政权的大规模兼并。法兰西瓦罗亚家族的国王们刚刚巩固了在国内的地位,便急欲将其势力侵入富饶的意大利半岛,在他们看来,查理五世的产业包围了法兰西国家。不夸张地讲,在以后的两个世纪里,法国在欧洲的目标就是要打破哈布斯堡家族的势力。同样,德意志的王公和帝侯长期以来一直就反对让皇帝在德意志本土有任何实权。他们看到,查理五世由于新添领土而实力大增,他可能会运用这些资源推行自己的主张,因而不能不警觉。许多教皇也如此,尽管他们经常需要利用哈布斯堡家族的势力,去同土耳其人、路德派及其他敌人战斗,但他们仍不愿让其权力扩大。

Given the rivalries endemic to the European states system, therefore, it was hardly likely that the Habsburgs would remain unchallenged. What turned this potential for conflict into a bitter and prolonged reality was its conjunction with the religious disputes engendered by the Reformation. For the fact was that the most prominent and powerful Habsburg monarchs over this century and a half—the Emperor Charles V himself and his later successor, Ferdinand II (1619–1637), and the Spanish kings Philip II (1556–1598) and Philip IV (1621–1665)—were also the most militant in the defense of Catholicism. As a consequence, it became virtually impossible to separate the power-political from the religious strands of the European rivalries which racked the continent in this period. As any contemporary could appreciate, had Charles V succeeded in crushing the Protestant princes of Germany in the 1540s, it would have been a victory not only for the Catholic faith but also for Habsburg influence—and the same was true of Philip II’s efforts to suppress the religious unrest in the Netherlands after 1566; and true, for that matter, of the dispatch of the Spanish Armada to invade England in 1588. In sum, national and dynastic rivalries had now fused with religious zeal to make men fight on where earlier they might have been inclined to compromise.

由于欧洲国家体系所固有的竞争机制,很难想像哈布斯堡王朝会不受挑战。这种冲突的可能性与宗教改革引起的教派纠纷相结合,就变成了旷日持久的、灾难性的现实冲突。事实是,在一个半世纪里,最为出色、最有权力的哈布斯堡君主,也是保卫天主教的最顽强的斗士。如查理五世及其继承人斐迪南二世(1619—1637年在位)、西班牙国王费利普二世(1556—1598年在位)、费利普四世(1621—1665年在位)都是如此。结果,企图把这个时期折磨欧洲大陆的竞争中的政治权力和宗教派系分离的想法全部落空。当时任何人都可以体会到,如果查理五世能在16世纪40年代打垮德国新教王公,那将不仅是天主教信仰的胜利,而且是哈布斯堡势力的胜利。同样情形还有,费利普二世在1566年以后镇压尼德兰宗教动乱;1588年,西班牙舰队入侵英格兰。简言之,民族和王朝的竞争现在与宗教狂热融为一体,使得人们不断寻求战争,而在以往,他们是可以妥协的。

Even so, it may appear a little forced to use the title “The Habsburg Bid for Mastery” to describe the entire period from the accession of Charles V as Holy Roman emperor in 1519 to the Spanish acknowledgment of defeat at the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659. Obviously, their enemies did firmly believe that the Habsburg monarchs were bent upon absolute domination. Thus, the Elizabethan writer Francis Bacon could in 1595 luridly describe the “ambition and oppression of Spain”:

即使如此,使用“哈布斯堡家族争霸”这个标题,概括从1519年查理五世当上神圣罗马帝国皇帝到1659年西班牙在《比利牛斯和约》上认输的整个时期,仍有些过分。显然,他们的敌人确实认为哈布斯堡家族想要掌握绝对的控制权。伊丽莎白时代的作家弗兰西斯·培根在1595年就曾伤感地描述了“西班牙的野心与压迫”:

France is turned upside down. … Portugal usurped. … The Low Countries warred upon. … The like at this day attempted upon Aragon. … The poor Indians are brought from free men to be slaves. 4

法兰西已被颠覆,……葡萄牙也被篡夺,……低地国家遭战火,……阿拉贡终难放过,……自由人沦为奴隶,印第安人悲惨啊!

But despite the occasional rhetoric of some Habsburg ministers about a “world monarchy,”5 there was no conscious plan to dominate Europe in the manner of Napoleon or Hitler. Some of the Habsburg dynastic marriages and successions were fortuitous, at the most inspired, rather than evidence of a long-term scheme of territorial aggrandizement. In certain cases—for example, the frequent French invasions of northern Italy—Habsburg rulers were more provoked than provoking. In the Mediterranean after the 1540s, Spanish and imperial forces were repeatedly placed on the defensive by the operations of a revived Islam.

尽管有些哈布斯堡大臣夸夸其谈,偶尔提到“世界君主”,但从没有一个像拿破仑或希特勒那样有意识、有计划地控制欧洲。有些哈布斯堡王朝的联姻和继承权属于幸运,最多不过是出于灵感,尚无证据说明是一个长期的领土扩张计划。在有些情况下,哈布斯堡统治者是受到挑衅,而不是去挑起事端。例如法国对意大利北部频繁的进攻。16世纪40年代以后,在地中海地区,西班牙及其帝国的部队因不断遭受复兴起来的伊斯兰国家的进攻而处于守势。

Nevertheless, the fact remains that had the Habsburg rulers achieved all of their limited, regional aims—even their defensive aims—the mastery of Europe would virtually have been theirs. The Ottoman Empire would have been pushed back, along the North African coast and out of eastern Mediterranean waters. Heresy would have been suppressed within Germany. The revolt of the Netherlands would have been crushed. Friendly regimes would have been maintained in France and England. Only Scandinavia, Poland, Muscovy, and the lands still under Ottoman rule would not have been subject to Habsburg power and influence—and the concomitant triumph of the Counter-Reformation. Although Europe even then would not have approached the unity enjoyed by Ming China, the political and religious principles favored by the twin Habsburg centers of Madrid and Vienna would have greatly eroded the pluralism that had so long been the continent’s most important feature.

无论如何,事实仍然是,只要哈布斯堡统治者达到他们有限的、地区性的目标,甚至是防御性的目标,欧洲霸权就在他们的掌握之中。奥斯曼帝国将被挡回去,沿北非海岸退出地中海;德国内部异教派将被压制下去,尼德兰起义将被扑灭;法兰西和英格兰的友好政权会保持下去。只有斯堪的纳维亚、波兰、莫斯科公国和奥斯曼帝国的残余领土不服从哈布斯堡政权。同时还有反宗教改革的胜利。虽然如此,那时的欧洲与明代中国所达到的统一程度相比仍是望尘莫及的。然而,哈布斯堡王朝的两个中心(马德里和维也纳)所主张的政治和宗教原则,将严重侵蚀欧洲大陆的多元性,而长期以来,这种多元性正是欧洲最重要的特点。

The chronology of this century and a half of warfare can be summarized briefly in a work of analysis like this. What probably strikes the eye of the modern reader much more than the names and outcome of various battles (Pavia, Lützen, etc. ) is the sheer length of these conflicts. The struggle against the Turks went on decade after decade; Spain’s attempt to crush the Revolt of the Netherlands lasted from the 1560s until 1648, with only a brief intermission, and is referred to in some books as the Eighty Years War; while the great multidimensional conflict undertaken by both Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs against successive coalitions of enemy states from 1618 until the 1648 Peace of Westphalia has always been known as the Thirty Years War. This obviously placed a great emphasis upon the relative capacities of the different states to bear the burdens of war, year after year, decade after decade. And the significance of the material and financial underpinnings of war was made the more critical by the fact that it was in this period that there took place a “military revolution” which transformed the nature of fighting and made it much more expensive than hitherto. The reasons for that change, and the chief features of it, will be discussed shortly. But even before going into a brief outline of events, it is as well to know that the military encounters of (say) the 1520s would appear very small-scale, in terms of both men and money deployed, compared with those of the 1630s.

在此简要分析上述一个半世纪的战争年表,对现代读者来说,引人注目的不是各个战役的名称和结果(如帕维亚、吕岑等),而是这些冲突所拖延的时间。与土耳其的战争拖了几十年;西班牙从16世纪60年代到1648年镇压尼德兰起义,其间只有一小段间歇,史称“八十年战争”;由奥地利和西班牙的哈布斯堡王室为一方、以敌对国家不断组成的联盟为另一方的范围广泛的冲突,从1618年拖到1648年签订威斯特伐利亚和平协定,则被人们称为“三十年战争”。在这种冲突中,每个国家承受一年复一年、十年复十年的战争负担的相对能力十分重要。正是在此时期,发生了一场“军事革命”,改变了战斗的性质,使以后战争耗费猛增,支撑战争的物质与财政的重要性更为突出。这个变化的原因及其主要特点,下面很快就要讨论到。但在我们对事件进行简略的描述之前,也应该知道,16世纪20年代的军事冲突,比17世纪30年代的军事冲突,无论在投入的人力,还是在使用的物力方面,其规模都要小得多。

The first series of major wars focused upon Italy, whose rich and vulnerable citystates had tempted the French monarchs to invade as early as 1494—and, with equal predictability, had produced various coalitions of rival powers (Spain, the Austrian Habsburgs, even England) to force the French to withdraw. 6 In 1519, Spain and France were still quarreling over the latter’s claim to Milan when the news arrived of Charles V’s election as Holy Roman emperor and of his combined inheritance of the Spanish and Austrian territories of the Habsburg family. This accumulation of titles by his archrival drove the ambitious French king, Francis I (1515–1547), to instigate a whole series of countermoves, not just in Italy itself, but also along the borders of Burgundy, the southern Netherlands, and Spain. Francis I’s own plunge into Italy ended in his defeat and capture at the battle of Pavia (1525), but within another four years the French monarch was again leading an army into Italy—and was again checked by Habsburg forces. Although Francis once more renounced his claims to Italy at the 1529 Treaty of Cambrai, he was at war with Charles V over those possessions both in the 1530s and in the 1540s.

第一系列的主要战争集中在意大利。早在1494年,意大利富饶而脆弱的城邦国家已遭致法国君主的入侵。同样可以预料的是,它们也促使各种竞争势力(西班牙、奥地利的哈布斯堡,甚至于英格兰)组成联盟,逼迫法国人后退。1519年,正当西班牙和法国还在为后者对米兰的权力争执时,传来了消息:查理五世当选为神圣罗马帝国皇帝,并继承哈布斯堡王朝在西班牙和奥地利的遗产。于是,野心勃勃的法兰西国王弗兰西斯一世(1515—1547年在位)看到自己的劲敌有如此之多的头衔,就极力在意大利本土并沿勃艮第边境、西班牙和南尼德兰挑起一系列反对活动。弗兰西斯一世进入意大利的结果是,在帕维亚战役中兵败就擒。不到4年,这位法国君主又率军开赴意大利,同样被哈布斯堡军队挫败。尽管弗兰西斯在1529年的康布雷条约上再一次宣布放弃对意大利的权利,但是在16世纪30年代和40年代,他仍与查理五世为这些领地进行战争。

Given the imbalance in forces between France and the Habsburg territories at this time, it was probably not too difficult for Charles V to keep blocking these French attempts at expansion. The task became the harder, however, because as Holy Roman emperor he had inherited many other foes. Much the most formidable of these were the Turks, who not only had expanded across the Hungarian plain in the 1520s (and were besieging Vienna in 1529), but also posed a naval threat against Italy and, in conjunction with the Barbary corsairs of North Africa, against the coasts of Spain itself. 7 What also aggravated this situation was the tacit and unholy alliance which existed in these decades between the Ottoman sultan and Francis I against the Habsburgs: in 1542, French and Ottoman fleets actually combined in an assault upon Nice.

由于法兰西与哈布斯堡的领土、实力大不一样,按说查理五世不难挡住法国的扩张。但作为神圣罗马帝国的皇帝,查理五世也承继了很多其他敌人,因而使这项使命难以完成。其中最为可怕的是土耳其人,他们在16世纪20年代扩张到匈牙利平原(在1529年包围了维也纳),并对意大利构成海上威胁;此外,他们与北非海盗勾结,袭击西班牙海岸。更为严重的是,奥斯曼帝国与弗兰西斯一世达成默契,组建反哈布斯堡的非神圣联盟:1542年,法国和奥斯曼的舰队联合进攻尼斯。

Charles V’s other great area of difficulty lay in Germany, which had been torn asunder by the Reformation and where Luther’s challenge to the old order was now being supported by a league of Protestant princely states. In view of his other problems, it was scarcely surprising that Charles V could not concentrate his energies upon the Lutheran challenge in Germany until after the mid-1540s. When he did so, he was at first quite successful, especially by defeating the armies of the leading Protestant princes at the battle of Mühlberg (1547). But any enhancement of Habsburg and imperial authority always alarmed Charles V’s rivals, so that the northern German princes, the Turks, Henry II of France (1547–1559), and even the papacy all strove to weaken his position. By 1552, French armies had moved into Germany, in support of the Protestant states, who were thereby able to resist the centralizing tendencies of the emperor. This was acknowledged by the Peace of Augsburg (1555), which brought the religious wars in Germany to a temporary end, and by the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis (1559), which brought the Franco-Spanish conflict to a close. It was also acknowledged, in its way, by Charles V’s own abdications—in 1555 as Holy Roman emperor to his brother Ferdinand I (emperor, 1555–1564), and in 1556 as king of Spain in favor of his son Philip II (1556–1598). If the Austrian and Spanish branches remained closely related after this time, it now was the case (as the historian Mamatey puts it) that “henceforth, like the doubleheaded black eagle in the imperial coat of arms, the Habsburgs had two heads at Vienna and at Madrid, looking east and west. ”8

查理五世的另一困境在德意志。这里已被宗教改革所分裂,路德对旧秩序的挑战得到新教公国同盟的支持。考虑到查理五世的其他困难,就不奇怪为什么他到16世纪40年代中期才集中力量对付路德派在德意志的挑战。查理五世的行动,开始十分成功,特别是在米尔贝格战役(1547)中击败由新教公国指挥的军队。但只要哈布斯堡和帝国权威一扩大,查理五世的竞争者就立刻紧张起来,于是德意志内部的公国、土耳其人、法兰西的亨利二世(1547—1559年在位)、甚至于教皇,全都力图削弱他的势力。1552年,法军开进德意志,以支持新教国,这些新教国得以抵制皇帝的中央集权倾向。这一点在暂时结束德国宗教战争的奥格斯堡和约(1555)和结束法、西冲突的卡托·坎布雷奇条约(1559)上都得到承认。查理五世退位本身也表明了这一点。他在1555年把神圣罗马帝国的皇位让给弟弟斐迪南一世(1555—1564年在位);1556年将西班牙王位让给儿子费利普二世(1556—1598年在位)。如果说此后奥地利和西班牙的两个支系仍然密切相关,那么,其情形恰如历史学家马玛泰所言:从此,犹如帝国纹章上的黑色双头鹰,哈布斯堡拥有两个头,一个在维也纳,一个在马德里;一个窥视东方,一个窥视西方。

While the eastern branch under Ferdinand I and his successor Maximilian II (emperor, 1564–1576) enjoyed relative peace in their possession (save for a Turkish assault of 1566–1567), the western branch under Philip II of Spain was far less fortunate. The Barbary corsairs were attacking the coasts of Portugal and Castile, and behind them the Turks were resuming their struggle for the Mediterranean. In consequence, Spain found itself repeatedly committed to major new wars against the powerful Ottoman Empire, from the 1560 expedition to Djerba, through the tussle over Malta in 1565, the Lepanto campaign of 1571, and the dingdong battle over Tunis, until the eventual truce of 1581. 9 At virtually the same time, however, Philip’s policies of religious intolerance and increased taxation had kindled the discontents in the Habsburg-owned Netherlands into an open revolt. The breakdown of Spanish authority there by the mid-1560s was answered by the dispatch northward of an army under the Duke of Alba and by the imposition of a military despotism—in turn provoking full-scale resistance in the seagirt, defensible Dutch provinces of Holland and Zee-land, and causing alarm in England, France, and northern Germany about Spanish intentions. The English were even more perturbed when, in 1580, Philip II annexed neighboring Portugal, with its colonies and its fleet. Yet, as with all other attempts of the Habsburgs to assert (or extend) their authority, the predictable result was that their many rivals felt obliged to come in, to prevent the balance of power becoming too deranged. By the 1580s, what had earlier been a local rebellion by Dutch Protestants against Spanish rule had widened into a new international struggle. 10 In the Netherlands itself, the warfare of siege and countersiege continued, without spectacular results. Across the Channel, in England, Elizabeth I had checked any internal (whether Spanish or papal-backed) threats to her authority and was lending military support to the Dutch rebels. In France, the weakening of the monarchy had led to the outbreak of a bitter religious civil war, with the Catholic League (supported by Spain) and their rivals the Huguenots (supported by Elizabeth and the Dutch) struggling for supremacy. At sea, Dutch and English privateers interrupted the Spanish supply route to the Netherlands, and took the fight farther afield, to West Africa and the Caribbean.

正当东部支系斐迪南一世及其承继人马克西米利安二世(1564—1576年任皇帝)在领地上享受相对和平的时候(不算土耳其人在1566年至1567年的进攻),西部支系西班牙的统治者费利普却十分不幸。北非海盗进攻葡萄牙和卡斯提尔海岸,土耳其人随后开始重新争夺地中海。结果,西班牙不得不与强大的奥斯曼帝国进行大规模的新战争,从1560年出征杰尔巴,经1565年在马耳他的搏斗,1571年勒班陀战役,以及各有胜负的突尼斯争夺战,直至1581年方实现最后的停战。与此同时,费利普的宗教褊狭政策和日益增加的赋税使尼德兰的哈布斯堡属民由愤愤不满变成公开起义。16世纪60年代中期,尼德兰的西班牙政权崩溃,导致阿尔巴公爵率军北上,实行军事专制。这反而导致四面环海,易于防卫,由荷兰和西兰岛所组成的荷兰人省份的全面抵抗,造成英国、法国和北德意志对西班牙人所怀意图的不安。1580年当费利普二世兼并邻国葡萄牙连同它的殖民地和舰队时,英国人更加心慌意乱。然而,正像哈布斯堡家族要强化(或扩展)权力的所有企图一样,其结果只能是他们的众多竞争对手觉得有责任进行干预,以防止权力平衡过于失调。到16世纪80年代,原本是荷兰新教徒反抗西班牙统治的地方性起义,已经扩展成一场新的国际斗争。在尼德兰本土,攻城和反攻城持续不断,毫无惊人结果。海峡彼岸的英格兰,伊丽莎白一世顶住内部对其权威的所有挑战(不论支持来自西班牙还是教皇),坚定地向荷兰起义者提供军事援助。在法国,君主政权的削弱导致一场激烈的宗教内战,由西班牙支持的天主教同盟与其对手——受伊丽莎白和荷兰人支持的胡格诺派拼死相争。在海上,荷兰、英国的私掠船则切断西班牙对尼德兰的补给线,并将战火引到西非和加勒比海。

At some periods in the struggle, especially in the late 1580s and early 1590s, it looked as if the powerful Spanish campaign would succeed; in September 1590, for example, Spanish armies were operating in Languedoc and Britanny, and another army under the outstanding commander the Duke of Parma was marching upon Paris from the north. Nevertheless, the lines of the anti-Spanish forces held, even under that sort of pressure. The charismatic French Huguenot claimant to the crown of France, Henry of Navarre, was flexible enough to switch from Protestantism to Catholicism to boost his claims—and then to lead an ever-increasing part of the French nation against the invading Spaniards and the discredited Catholic League. By the 1598 Peace of Vervins—the year of the death of Philip II of Spain—Madrid agreed to abandon all interference in France. By that time, too, the England of Elizabeth was also secure. The great Armada of 1588, and two later Spanish invasion attempts, had failed miserably—as had the effort to exploit a Catholic rebellion in Ireland, which Elizabeth’s armies were steadily reconquering. In 1604, with both Philip II and Elizabeth dead, Spain and England came to a compromise peace. It would take another five years, until the truce of 1609, before Madrid negotiated with the Dutch rebels for peace; but well before then it had become clear that Spanish power was insufficient to crush the Netherlands, either by sea or through the strongly held land (and watery) defenses manned by Maurice of Nassau’s efficient Dutch army. The continued existence of all three states, France, England, and the United Provinces of the Netherlands, each with the potential to dispute Habsburg pretensions in the future, again confirmed that the Europe of 1600 would consist of many nations, and not of one hegemony.

这场斗争的某些阶段,特别是16世纪80年代后期和16世纪90年代初期,声势浩大的西班牙战役看来就要胜利了。例如1590年9月,西班牙军队在朗格多克和布列塔尼作战;另一支军队在帕尔马公爵出色指挥下由北方进军巴黎。尽管有这样的压力,反西班牙的部队还是顶住了。法兰西王冠的竞争者、颇具魅力的法国胡格诺教徒、纳瓦尔的亨利,为了争取对他的王位的支持,在教派归属上灵活到可从新教徒转信天主教;然后,又领导越来越多的法兰西民众去反对入侵的西班牙人和声名狼藉的天主教同盟。到1598年,《韦尔芬和平协议》达成,正值西班牙国王费利普二世去世,马德里同意放弃对法兰西的一切干涉。到这个时候,伊丽莎白的英国也保住了。1588年西班牙的无敌舰队的两次入侵均遭惨败,在爱尔兰挑动天主教起义的企图也破灭了,伊丽莎白的军队稳固地重新征服了爱尔兰。1604年费利普二世和伊丽莎白都已去世,西班牙同英格兰妥协言和。又经过5年,直到1609年,马德里才与荷兰起义者停战,谈判和平协议。虽然在此之前,局势早已清楚:无论是从海上,还是经由莫里斯指挥的战斗力极强的荷兰军队坚守的拿骚陆地(和水路),西班牙政权都无法击溃尼德兰。法兰西、英格兰和尼德兰联合省这三个国家继续存在,而每个国家都有潜力干扰哈布斯堡家族未来统治的事实,再一次肯定了1600年的欧洲是由众多国家组成的,而不是只有一个霸主。

The third great spasm of wars which convulsed Europe in this period occurred after 1618, and fell very heavily upon Germany. That land had been spared an allout confessional struggle in the late sixteenth century, but only because of the weakening authority and intellect of Rudolf II (Holy Roman emperor, 1576–1612) and a renewal of a Turkish threat in the Danube basin (1593–1606). Behind the facade of German unity, however, the rival Catholic and Protestant forces were maneuvering to strengthen their own position and to weaken that of their foes. As the seventeenth century unfolded, the rivalry between the Evangelical Union (founded in 1608) and the Catholic League (1609) intensified. Moreover, because the Spanish Habsburgs strongly supported their Austrian cousins, and because the head of the Evangelical Union, the Elector Palatine Frederick IV, had ties with both England and the Netherlands, it appeared as if most of the states of Europe were lining up for a final settlement of their political-religious antagonisms. 11

这一时期震撼欧洲的第三次大交战发生在1618年以后,德意志身遭重创。仅仅因为鲁道夫二世(1576—1612年任神圣罗马帝国皇帝)的权力削弱和他个人的才智,以及土耳其对多瑙河流域的再次威胁(1593—1606),德意志在16世纪后期才幸免于一场全面的教派战争。然而,在德意志团结一致的表象背后,敌对的天主教和新教势力都在想方设法加强自己的实力,削弱敌方的力量。17世纪初,福音派联盟(建于1608年)和天主教同盟(建于1609年)的斗争加剧。况且,西班牙的哈布斯堡家族坚决支持他们在奥地利的表兄弟,而福音派联盟的首领,即帕拉泰恩·弗莱德里克第四选侯与英格兰和尼德兰都有关系,于是,欧洲多数国家都加入各自阵线,似乎准备为他们的政治、宗教矛盾决一死战。

The 1618 revolt of the Protestant estates of Bohemia against their new Catholic ruler, Ferdinand II (emperor 1619–1637), therefore provided the spark needed to begin another round of ferocious religious struggles: the Thirty Years War of 1618– 1648. In the early stages of this contest, the emperor’s forces fared well, ably assisted by a Spanish-Habsburg army under General Spinola. But, in consequence, a heterogeneous combination of religious and worldly forces entered the conflict, once again eager to adjust the balances in the opposite direction. The Dutch, who ended their 1609 truce with Spain in 1621, moved into the Rhineland to counter Spinola’s army. In 1626, a Danish force under its monarch Christian IV invaded Germany from the north. Behind the scenes, the influential French statesman Cardinal Richelieu sought to stir up trouble for the Habsburgs wherever he could. However, none of these military or diplomatic countermoves were very successful, and by the late 1620s the Emperor Ferdinand’s powerful lieutenant, Wallenstein, seemed well on the way to imposing an all-embracing, centralized authority on Germany, even as far north as the Baltic shores. 12

1618年波希米亚的新教集团反对新的天主教统治者斐迪南二世(1619—1637年在位)的起义,为另一轮残酷的宗教战争,即1618年至1648年的“三十年战争”的爆发提供了所需的导火索。斗争开始,皇帝的军队进展顺利,斯帕诺拉率领的西班牙哈布斯堡军队有效地支援了他们。然而结果却是,一群成分复杂的宗教和世俗军事力量卷入冲突,于是又一次急切地需要改变力量对比的方向。荷兰人在1621年终止了与西班牙在1609年达成的停战,开进莱茵兰与斯帕诺拉的军队对抗。1626年,一支丹麦军队在它的君主克里斯琴四世的率领下,从北方进攻德意志。在幕后,颇具影响力的法国政治家、红衣主教黎塞留想尽一切办法给哈布斯堡家族制造麻烦。不过,这些军事的和外交的反攻均未奏效。到17世纪20年代末期,斐迪南皇帝的有权势的副官华伦斯坦简直就要把包容一切的中央集权的政府强加到德意志身上,其范围甚至远及北部波罗的海沿岸。

Yet this rapid accumulation of imperial power merely provoked the House of Habsburgs many enemies to strive the harder. In the early 1630s by far the most decisive of them was the attractive and influential Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus II (1611–1632), whose well-trained army moved into northern Germany in 1630 and then burst southward to the Rhineland and Bavaria in the following year. Although Gustavus himself was killed at the battle of Lützen in 1632, this in no way diminished the considerable Swedish role in Germany—or, indeed, the overall dimensions of the war. On the contrary, by 1634 the Spaniards under Philip IV (1621–1665) and his accomplished first minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares, had decided to aid their Austrian cousins much more thoroughly than before; but their dispatch into the Rhineland of a powerful Spanish army under its general, Cardinal- Infante, in turn forced Richelieu to decide upon direct French involvement, ordering troops across various frontiers in 1635. For years beforehand, France had been the tacit, indirect leader of the anti-Habsburg coalition, sending subsidies to all who would fight the imperial and Spanish forces. Now the conflict was out in the open, and each coalition began to mobilize even more troops, arms, and money. The language correspondingly became stiffen “Either all is lost, or else Castile will be head of the world,” wrote Olivares in 1635, as he planned the triple invasion of France in the following year. 13

帝国政权的迅速强化,激起哈布斯堡家族的众多仇敌更加奋力地与之拼搏。17世纪30年代初期,最坚决果敢的人当属引人注目、有影响的瑞典国王古斯塔夫·阿道弗斯二世(1611—1632年在位),1630年,其训练有素的军队挺进德意志北部,翌年,向南冲入莱茵兰和巴伐利亚。虽然古斯塔夫在1632年的吕岑战役中阵亡,但绝不能就此抵消瑞典对德意志的举足轻重的作用,或者说,抵消这场战争的巨大规模。反之,到1634年,费利普四世(1621—1665年在位)和其才华不凡的首相奥里瓦列斯公爵所率领的西班牙人,决定给他们的奥地利表兄弟以更全面的支援,但他们派往莱茵兰的、以红衣主教茵凡特为主将的军队,反而促使黎塞留决定法国直接卷入,于1653年命令军队在多处跨过边界。多年以来,法兰西一直是反哈布斯堡联盟的默契的、间接的领袖,向所有反帝国和西班牙的人送去津贴。现在冲突已公开,每个联盟开始动员更多的军队、武器、钱财。讲话的语言也相应地变得更加强硬。奥里瓦列斯在1635年制定下一年三路进攻法国的计划时曾写道:“要么丧失一切,要么使卡斯提尔居世界之首。”

The conquest of an area as large as France was, however, beyond the military capacities of the Habsburg forces, which briefly approached Paris but were soon hard stretched across Europe. Swedish and German troops were pressing the imperial armies in the north. The Dutch and the French were “pincering” the Spanish Netherlands. Moreover, a revolt by the Portuguese in 1640 diverted a steady flow of Spanish troops and resources from northern Europe to much nearer home, although they were never enough to achieve the reunification of the peninsula. Indeed, with the parallel rebellion of the Catalans—which the French gladly aided—there was some danger of a disintegration of the Spanish heartland by the early 1640s. Overseas, Dutch maritime expeditions struck at Brazil, Angola, and Ceylon, turning the conflict into what some historians describe as the first global war. 14 If the latter actions brought gains to the Netherlands, most of the other belligerents were by this time suffering heavily from the long years of military effort; the armies of the 1640s were becoming smaller than those of the 1630s, the financial expedients of governments were the more desperate, the patience of the people was much thinner and their protests much more violent. Yet precisely because of the interlinked nature of the struggle, it was difficult for any one participant to withdraw. Many of the Protestant German states would have done just that, had they been certain that the Swedish armies would also cease fighting and go home; and Olivares and other Spanish statesmen would have negotiated a truce with France, but the latter would not desert the Dutch. Secret peace negotiations at various levels were carried out in parallel with military campaigns on various fronts, and each power consoled itself with the thought that another victory would buttress its claims in the general settlement.

然而,征服法兰西这样一个大国是哈布斯堡的军事力量所力不能及的。其军队刚刚接近巴黎,就被迫拉长战线,横跨欧洲。瑞典和德意志军队在北方进逼帝国军队。荷兰和法国“钳住”西属尼德兰。更糟的是,1640年葡萄牙起义使一部分西班牙军队和物资不得不源源不断地从北欧转移到本土,尽管这些兵力和资源还不足以重新统一这个半岛。实际上,同时发生的加泰罗尼亚人的起义受到法国人热情的支持,希望它在17世纪40年代初期有可能造成西班牙腹地的分裂。在海外,荷兰远征舰队袭击巴西、安哥拉和锡兰,将冲突转变成某些历史学家所说的第一次全球性战争。如果说尼德兰在后几项活动中获得好处,那么,其他交战国这时大都因多年的军事活动而损失惨重。17世纪40年代的军队比30年代要少些,各国政府的财政应急措施更加不顾一切,人民已失去耐心,抗议日趋猛烈。然而,正因为这是一场相互牵连的斗争,参加的任何一方都难于退出。很多德意志的新教国家要是知道瑞典也愿停战回家,他们就会退出。奥里瓦列斯和其他西班牙政治家有可能与法国谈判停火,但后者不肯抛弃荷兰。不同级别的秘密谈判与各条战线上的军事行动在同时并进,每方都私下安慰自己说,再打一次胜仗就能加强自己在总体和解中的地位。

The end of the Thirty Years War was, in consequence, an untidy affair. Spain suddenly made peace with the Dutch early in 1648, finally recognizing their full independence; but this was done to deprive France of an ally, and the Franco- Habsburg struggle continued. It became purely a Franco-Spanish one later in the year when the Peace of Westphalia (1648) at last brought tranquillity to Germany, and allowed the Austrian Habsburgs to retire from the conflict. While individual states and rulers made certain gains (and suffered certain losses), the essence of the Westphalian settlement was to acknowledge the religious and political balance within the Holy Roman Empire, and thus to confirm the limitations upon imperial authority. This left France and Spain engaged in a war which was all to do with national rivalries and nothing to do with religion—as Richelieu’s successor, the French minister, Mazarin, clearly demonstrated in 1655 by allying with Cromwell’s Protestant England to deliver the blows which finally caused the Spaniards to agree to a peace. The conditions of the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) were not particularly harsh, but in forcing Spain to come to terms with its great archenemy, they revealed that the age of Habsburg predominance in Europe was over. All that was left as a “war aim” for Philip IV’s government then was the preservation of Iberian unity, and even this had to be abandoned in 1668, when Portugal’s independence was formally recognized. 15 The continent’s political fragmentation thus remained in much the same state as had existed at Charles V’s accession in 1519, although Spain itself was to suffer from further rebellions and losses of territory as the seventeenth century moved to its close (see Map 4)—paying the price, as it were, for its original strategical overextension.

因而“三十年战争”的结局并不干脆利落。西班牙之所以突然在1648年初与荷兰和解,承认后者的完全独立,不过是为了剥夺法国的一个盟友。法兰西与哈布斯堡的斗争仍在继续。同年,当《威斯特伐利亚和约》(1648)终于给德意志带来平静时,奥地利的哈布斯堡家族退出了冲突。余下的纯粹是法、西冲突。《威斯特伐利亚和约》使个别国家和统治者有失有得,其精髓是要承认神圣罗马帝国内部的宗教与政治的均势,确认帝国权威的局限性。这就使得西班牙和法兰西留下来进行一场民族战争,而与宗教毫无关系。黎塞留的继承人、法国首相马扎林清楚地证实了这一点。1655年,他与克伦威尔的新教英国结盟,打击西班牙,迫使它同意和谈。《比利牛斯和约》(1659)的条款并不苛刻,但西班牙被迫与自己的劲敌和解,足以说明哈布斯堡家族已在欧洲丧失了优势。费利普四世政府所剩下的“战争目标”只是保全伊比利亚半岛的统一,甚至这个目标也不得不在1688年放弃。因为那时葡萄牙的独立已获得正式承认。欧洲大陆的政治分裂仍然保持着查理五世1519年继位时的大致状况,尽管西班牙本身在17世纪末仍需为它最初过分的战略扩张付出代价,遭受更多的起义和领土损失的折磨(见地图4)。