Strengths and Weaknesses of the Habsburg Bloc

二 实力与弱点

Why did the Habsburgs fail?16 This issue is so large and the process was so lengthy that there seems little point in looking for personal reasons like the madness of the Emperor Rudolf II, or the incompetence of Philip III of Spain. It is also difficult to argue that the Habsburg dynasty and its higher officers were especially deficient when one considers the failings of many a contemporary French and English monarch, and the venality or idiocy of some of the German princes. The puzzle appears the greater when one recalls the vast accumulation of material power available to the Habsburgs:

哈布斯堡家族为什么会失败?这个问题如此复杂,过程又如此漫长,看来很难用个人因素来解释,比如说鲁道夫二世皇帝的疯狂,或者西班牙费利普三世的无能。也很难说哈布斯堡王朝和它的官员们特别无能,看看同时代法国和英国许多君主的失败,以及某些德意志王公的贪赃愚昧就足矣了。回想一下哈布斯堡家族所能积聚和掌握的大量物质力量就更令人困惑费解。

Charles V’s inheritance of the crowns of four major dynasties, Castile, Aragon, Burgundy, and Austria, the later acquisitions by his house of the crowns of Bohemia, Hungary, Portugal, and, for a short time, even of England, and the coincidence of these dynastic events with the Spanish conquest and exploitation of the New World—these provided the house of Habsburg with a wealth of resources that no other European power could match. 17

查理五世继承了四个主要王朝的王冠,卡斯提尔、阿拉贡、勃艮第和奥地利,后来他的家族又得到波希米亚、匈牙利和葡萄牙,有一小段时间里甚至还得到英格兰的王冠。这些王朝事件的发生,加上同时西班牙在新世界的征服与掠夺——都给哈布斯堡家族带来了其他欧洲国家所不能比拟的财富和资源。

Given the many gaps and inaccuracies in available statistics, one should not place too much reliance upon the population figures of this time; but it would be fair to assume that about one-quarter of the peoples of early modern Europe were living in Habsburg-ruled territory. However, such crude totals* were less important than the wealth of the regions in question, and here the dynastic inheritance seemed to have been blessed with riches.

尽管现有统计数字有许多漏洞和不精确之处,那个时期的人口数字又不那么可靠,但假定居住在哈布斯堡统治的领土上的居民占近代早期欧洲人口的1/4,是不会大错的。然而,这些概略的总数[2]比起这些地区的财富并不那么重要,这里的王朝遗产看似得天独厚、非常富饶。

There were five chief sources of Habsburg finance, and several smaller ones. By far the most important was the Spanish inheritance of Castile, since it was directly ruled and regular taxes of various sorts (the sales tax, the “crusade” tax on religious property) had been conceded to the crown by the Cortes and the church. In addition, there were the two richest trading areas of Europe—the Italian states and the Low Countries—which could provide comparatively large funds from their mercantile wealth and mobile capital. The fourth source, increasingly important as time went on, was the revenue from the American empire. The “royal fifth” of the silver and gold mined there, together with the sales tax, customs duties, and church levies in the New World, provided a vast bonus to the kings of Spain, not only directly but also indirectly, for the American treasures which went into private hands, whether Spanish or Flemish or Italian, helped those individuals and concerns to pay the increasing state taxes levied upon them, and in times of emergency, the monarch could always borrow heavily from the bankers in the expectation of paying off his debts when the silver fleet arrived. The fact that the Habsburg territories contained the leading financial and mercantile houses—those of southern Germany, of certain of the Italian cities, and of Antwerp)—must be counted as an additional advantage, and as the fifth major source of income. 18 It was certainly more readily accessible than, say, revenues from Germany, where the princes and free cities represented in the Reichstag voted money to the emperor only if the Turks were at the door. 19

哈布斯堡家族有五项主要的财政来源,另有一些小项进款。其中最为重要的是西班牙的卡斯提尔遗产。此地由王室直接统治,议会和教会把各种定期的捐税让给王室(营业税、宗教财产“十字军税”)。此外,欧洲的两个贸易区——意大利城邦和低地国家——的商业财富和流动资本能够提供相当多的资金。第4项来源,随着时间的推移越来越重要,即来自美洲国家的收入。在美洲开采白银和黄金的“五分之一王室税”,加上营业税、关税,以及教会的征收,使得新世界为西班牙国王们提供了大笔红利,不仅是直接的,还有间接的,因为流进私人手里的美洲财富,不管是西班牙人、佛兰芒人或意大利人,都有助于这些个人或公司交纳越来越重的国税,而且在紧急情况下,君主还可以向银行家大量借款,因为运送白银的船队一到,他就可以付清债务。哈布斯堡家族领土内拥有很多重要的金融和商业大家族,例如住在德意志南部、意大利城市和安特卫普的那些富商巨贾,也应算作一种优势,这是第5项主要财政来源。举例来说,这项来源肯定比来自德意志的赋税更容易到手,因为德意志国会里的那些王公和自由城市的代表,只有在土耳其人攻到门口时,才肯投票给皇帝拨款。

In the postfeudal age, when knights were no longer expected to perform individual military service (at least in most countries) nor coastal towns to provide a ship, the availability of ready cash and the possession of good credit were absolutely essential to any state engaged in war. Only by direct payment (or promise of payment) could the necessary ships and naval stores and armaments and foodstuffs be mobilized within the market economy to furnish a fleet ready for combat; only by the supply of provisions and wages on a reasonably frequent basis could one’s own troops be steered away from mutiny and their energies directed toward the foe. Moreover, although this is commonly regarded as the age when the “nation-state” came into its own in western Europe, all governments relied heavily upon foreign mercenaries to augment their armies. Here the Habsburgs were again blessed, in that they could easily recruit in Italy and the Low Countries as well as in Spain and Germany; the famous Army of Flanders, for example, was composed of six main nationalities, reasonably loyal to the Catholic cause but still requiring regular pay. In naval terms, the Habsburg inheritance could produce an imposing conglomeration of fighting vessels: in Philip II’s later years, for example, Mediterranean galleys, great carracks from Genoa and Naples, and the extensive Portuguese fleet could reinforce the armadas of Castile and Aragon.

封建社会末期,骑士们已不可能再履行个人的军事服务(至少多数国家如此),沿海城镇也不可能提供船舶。对一个交战国家来说,拥有现金和可靠的信贷是绝对必要的。只有直接支付(或者承付)才能在市场经济的限度内购到必要的船只、海军设备、武器和食品来装备一支随时可以出战的舰队;只有相当频繁地向自己的军队提供给养和薪饷才能避免发生哗变,从而把军人的能量指向敌人。再说,此一时期虽是人们称之为西欧“民族国家”的产生时期,但所有的政府都大量依靠外国雇佣军来加强军事力量。这一点哈布斯堡家族又占了便宜,他们可以轻而易举地从意大利、低地国家以及西班牙和南德意志招兵。例如著名的佛兰德军就是由6个主要民族构成的,都相当忠实于天主教的事业,但需要按时付薪。说到海军,哈布斯堡的遗产可以组建一群五花八门的舰队,例如在费利普二世的晚年,地中海式军舰、热那亚和那不勒斯的大型西班牙式帆船、数量庞大的葡萄牙舰队,都可壮大卡斯提尔和阿拉贡的舰队。

But perhaps the greatest military advantage possessed by the Habsburgs during these 140 years was the Spanish-trained infantry. The social structure and the climate of ideas made Castile an ideal recruiting ground; there, notes Lynch, “soldiering had become a fashionable and profitable occupation not only for the gentry but for the whole population. ”20 In addition, Gonzalo de Córdoba, the “Great Captain,” had introduced changes in the organization of infantry early in the sixteenth century, and from then until the middle of the Thirty Years War the Spanish tercio was the most effective unit on the battlefields of Europe. With these integrated regiments of up to 3,000 pikemen, swordsmen, and arquebusiers, trained to give mutual support, the Spanish army swept aside innumerable foes and greatly reduced the reputation—and effectiveness—of French cavalry and Swiss pike phalanxes. As late as the battle of N?rdlingen (1634), Cardinal-Infante’s infantry resisted fifteen charges by the formidable Swedish army and then, like Wellington’s troops at Waterloo, grimly moved forward to crush their enemy. At Rocroi (1643), although surrounded by the French, the Spaniards fought to the death. Here, indeed, was one of the strongest pillars in the Habsburg edifice; and it is significant that Spanish power visibly cracked only in the mid-seventeenth century, when its army consisted chiefly of German, Italian, and Irish mercenaries with far fewer warriors from Castile.

不过,在这140年里,哈布斯堡家族最大的军事优势恐怕是西班牙训练的步兵。卡斯提尔的社会结构和思想氛围造就了一个理想的招兵场地,恰如林奇所指出的,在那儿“当兵是一种合乎时尚而又有利可图的行业,不仅对绅士而言如此,而且对全体人民亦然”。况且,那位“伟大的上尉”贡萨洛·德·科尔多瓦在16世纪初期对步兵的编制进行了改组,从那时起直到“三十年战争”中期,西班牙的“三重军”是欧洲战场上最具战斗力的军队。每团3 000人,枪兵、剑兵和火绳钩枪兵编制在一起,训练相互支援配合。西班牙运用这种兵团扫荡了无数敌人,大大降低了法国骑兵和瑞士枪兵方阵的名声和战斗力。一直到讷德林根战役(1634),茵凡特红衣主教的步兵还顶住了瑞士军队的15次强大攻势,然后,就像惠灵顿的军队在滑铁卢战场上那样,坚定地向前推进,粉碎敌人。在罗克鲁瓦(1643),西班牙人虽被法军包围,仍然战斗至死,这当然是哈布斯堡大厦中最坚固的支柱之一。值得注意的是,西班牙的军力直到17世纪中叶才明显地出现裂痕,那时的军队主要由德意志、意大利和爱尔兰的雇佣军组成,来自卡斯提尔的武士已大大减少。

Yet, for all these advantages, the Spanish-Austrian dynastic alliance could never prevail. Enormous though its financial and military resources appeared to contemporaries, there was never sufficient to meet requirements. This critical deficiency was itself due to three factors which interacted with each other over the entire period—and which, by extension, provide major lessons for the study of armed conflict.

尽管拥有上述优势,但西班牙-奥地利王朝同盟却绝不可能取胜。这是由于它的财政和军事资源虽然在当时的人看来极其雄厚,却从没有满足过要求。这个致命的缺陷来源于三个始终相互作用的因素。从广义上讲,它为研究军事冲突提供了主要素材。

The first of these factors, mentioned briefly above, was the “military revolution” of early modern Europe: that is to say, the massive increase in the scale, costs and organization of war which occurred in the 150 years roughly following the 1520s. 21 This change was itself the result of various intertwined elements, tactical, political, and demographic. The blows dealt to the battlefield dominance of cavalry—first by the Swiss pikemen and then by mixed formations of men bearing pikes, swords, crossbows, and arquebuses—meant that the largest and most important part of an army was now its infantry. This conclusion was reinforced by the development of the tracé italien, that sophisticated system of city fortifications and bastions mentioned in the previous chapter. To man such defensive systems, or to besiege them, required a very large number of troops. Of course, in a major campaign a well-organized commander would be successfully employing considerable numbers of cavalry and artillery as well, but those two arms were much less ubiquitous than regiments of foot soldiers. It was not the case, then, that nations scrapped their cavalry forces, but that the infantry proportion in their armies rose markedly; being cheaper to equip and feed, foot soldiers could be recruited in larger numbers, especially since Europe’s population was rising. Naturally, all this placed immense organizational strains upon governments, but not so great that they would necessarily overwhelm the bureaucracies of the “new monarchies” of the West—just as the vast increase in the size of the armies would not inevitably make a general’s task impossible, provided that his forces had a good command structure and were well drilled.

第一个因素,前面已简略地提过,即近代欧洲早期的“军事革命”,亦即约16世纪20年代以后的150年里,战争的规模、费用以及组织剧烈膨胀,这种变化本身是由几种交错因素造成的,有战术上的、政治上的和人口的因素。骑兵控制战场的格局受到打击,打击首先来自瑞士枪兵,然后是操长枪、剑、弩和火绳枪的混合部队,这意味着一个军队最大最重要的组成部分是步兵。“意大利式略图”的发展更加强了这个结论,也就是前面一章提到的高级复杂的城防梭堡系统。部署这样一个防卫系统或者围困它都需要数目庞大的军队。当然,在一场大战役中,一个有组织能力的指挥官同样能很好地部署相当数量的骑兵和炮兵,但这两种部队毕竟不像步兵团队那样无处不在。因此,并不是国家削弱它们的骑兵力量,而是步兵在军队中的比例显著增加;步兵的装备和给养都比较便宜,可以大量招收,特别是因为欧洲的人口在增长。当然,这些因素极大地增强了对政府组织工作的压力,但不会压垮西方“新式君主”的官僚体系,正如军队人员的大量增加并不一定能使一个将领丧失指挥能力一样,只要他的军队有一个出色的指挥机构,且受过良好训练就足矣。

The Spanish Empire’s army probably provides the best example of the “military revolution” in action. As its historian notes, “there is no evidence that any one state fielded more than 30,000 effectives” in the Franco-Spanish struggle for Italy before 1529; but:

西班牙帝国的军队也许为“军事革命”的实现提供了最好的榜样。正如研究它的历史学家所说,1529年以前,法国和西班牙在争夺意大利的斗争中,“没有证据说明任何一方使用3万以上的兵力”,但是:

In 1536–7 the Emperor Charles V mobilized 60,000 men in Lombardy alone for the defense of his recent conquest, Milan, and for the invasion of French Provence. In 1552, assailed on all fronts at once—in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain, in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean—Charles V raised 109,000 men in Germany and the Netherlands, 24,000 more in Lombardy and yet more in Sicily, Naples and Spain. The emperor must have had at his command, and therefore at his cost, about 150,000 men. The upward trend continued. In 1574 the Spanish Army of Flanders alone numbered 86,000 men, while only half a century later Philip IV could proudly proclaim that the armed forces at his command in 1625 amounted to no less than 300,000 men. In all these armies the real increase in numbers took place among the infantry, especially among the pikemen. 22

在1536—1537年,皇帝查理五世仅在伦巴底一地就征集6万人,保卫新占领的米兰,并入侵法国的普罗旺斯。1552年,为同时从所有战线进攻——在意大利、德意志、尼德兰和西班牙,在大西洋和地中海——查理五世在德意志和尼德兰征兵10.9万人,又从伦巴底征兵2.4万人,此外,还有从西西里、那不勒斯和西班牙征来的兵。这样,皇帝指挥下的、因而也是他供养的军队一定有15万人左右。这种上升趋势仍在继续。1574年,仅西班牙的佛兰德军就有8.6万人。而仅仅半个世纪以后,费利普四世也可以高傲地宣称,他在1625年指挥的军队不下3万人。在所有这些军队中,真正增长的部分是步兵,特别是枪兵。

What was happening on land was to a large extent paralleled at sea. The expansion in maritime (especially transoceanic) commerce, the rivalries among the contending fleets in the Channel, the Indian Ocean, or off the Spanish Main, the threats posed by the Barbary corsairs and the Ottoman galley fleets, all interacted with the new technology of shipbuilding to make vessels bigger and much better armed. In those days there was no strict division between a warship and a merchantmen; virtually all fair-sized trading vessels would carry guns, in order to beat off pirates and other predators. But there was a trend toward the creation of royal navies, so that the monarch would at least possess a number of regular warships to form the core around which a great fleet of armed merchantmen, galleasses, and pinnaces could gather in time of war. Henry VIII of England gave considerable support to this scheme, whereas Charles V tended to commandeer the privately owned galleons and galleys of his Spanish and Italian possessions rather than to build his own navy. Philip II, under far heavier pressure in the Mediterranean and then in the Atlantic, could not enjoy that luxury. He had to organize, and pay for, a massive program of galley construction, in Barcelona, Naples, and Sicily; by 1574 he was supporting a total of 146 galleys, nearly three times the number a dozen years before. 23 The explosion of warfare in the Atlantic during the following decade necessitated an even greater effort there: oceangoing warships were needed to protect the routes to the West Indies and (after Portugal was absorbed in 1580) to the East, to defend the Spanish coastline from English raids, and, ultimately, to convey an invading army to the British Isles. After the Anglo-Spanish peace of 1604, a large fleet was still required by Spain to ward off Dutch attacks on the high seas and to maintain communications with Flanders. And, decade by decade, such warships became heavier-armed and much more expensive.

在陆上所发生的事情,在海上以更大的规模发生了。海上贸易(特别是漂洋过海的贸易)的扩大,贸易国舰队在英吉利海峡、印度洋或西班牙本土沿海的竞争,北非海盗船和奥斯曼大型帆船舰队构成的威胁,都与新的造船技术相互作用,使得舰船造得越来越大,装备越来越先进。那个时代,战舰和商船并无明显界限,一定规格的商船基本上都装配枪炮,以对付海盗和其他掠夺者。但有一股建立皇家海军的潮流,君主可以借此占有一定数量的正规海军,形成一个核心。战时,武装的商船、三桅军舰以及二桅小型舰只可向这个核心集中靠拢。英格兰的亨利八世尤为支持这个方案,而查理五世却不愿自建海军,他更倾向于征用其西班牙和意大利领地上的私人西班牙式大帆船和单甲板大帆舰。费利普二世在地中海、接着在大西洋受到沉重压力,不可能享受这种奢侈,他不得不出钱在巴塞罗那、那不勒斯和西西里实施一个庞大的造船计划;到1574年,他供养了146只大帆船,几乎是十几年前的3倍。以后10年里,大西洋爆发的战争迫使他付出更大努力,以确保通往西印度群岛(1580年葡萄牙被吞并以后)和东印度群岛的海路,保护西班牙海岸免遭英国的袭击,以及把侵略军送往不列颠,这一切,都急需远洋舰队。1604年英西签订和约后,西班牙仍需一支庞大舰队,用以抵御荷兰人的海上进攻,保卫同佛兰德的交通。而且,天长日久、时光飞逝,这些战舰的装备越来越多,费用也越来越昂贵。

It was these spiraling costs of war which exposed the real weakness of the Habsburg system. The general inflation, which saw food prices rise fivefold and industrial prices threefold between 1500 and 1630, was a heavy enough blow to government finances; but this was compounded by the doubling and redoubling in the size of armies and navies. In consequence, the Habsburgs were involved in an almost continual struggle for solvency. Following his various campaigns in the 1540s against Algiers, the French, and the German Protestants, Charles V found that his ordinary and extraordinary income could in no way match expenditures, and his revenues were pledged to the bankers for years ahead. Only by the desperate measure of confiscating the treasure from the Indies and seizing all specie in Spain could the monies be found to support the war against the Protestant princes. His 1552 campaign at Metz cost 2. 5 million ducats alone—about ten times the emperor’s normal income from the Americas at that time. Not surprisingly, he was driven repeatedly to raise fresh loans, but always on worse terms: as the crown’s credit tumbled, the interest rates charged by the bankers spiraled upward, so that much of the ordinary revenue had to be used simply to pay the interest on past debts. 24 When Charles abdicated, he bequeathed to Philip II an official Spanish debt of some 20 million ducats.

正是这种螺旋式上升的战争费用暴露了哈布斯堡政权的真正弱点。普遍的通货膨胀使得食品价格从1500年到1630年上涨4倍,工业品价格上升2倍,这对政府的财政是一个极为沉重的打击,陆军和海军两倍、三倍地扩充规模,更是火上加油。结果,哈布斯堡家族总是不断地为具有偿付能力而挣扎。16世纪40年代,在对付了阿尔及尔、法国和德意志新教徒的种种战役之后,查理五世发现他的正常和非常收入,根本不能支付开销,他的赋税早已提前多年抵押给了银行家。只有采取断然措施,没收西印度群岛的财富,抓住西班牙所有的硬币,才能找到金钱,支撑对付新教王公的战争。1552年,他在梅斯一役中就花掉250万达卡,约为皇帝当时征自美洲的正常收入的10倍。不足为奇的是,他被迫不断地举借新债,但是条件越来越苛刻;王室的信用在下降,银行家征收的利息却越来越高,于是,正常收入的很大部分只能用来偿付以往债务的利息。查理退位时,留给费利普二世的国债已约有2 000万达卡。

Philip also inherited a state of war with France, but one which was so expensive that in 1557 the Spanish crown had to declare itself bankrupt. At this, great banking houses like the Fuggers were also brought to their knees. It was a poor consolation that France had been forced to admit its own bankruptcy in the same year—the major reason for each side agreeing to negotiate at Cateau-Cambresis in 1559—for Philip had then immediately to meet the powerful Turkish foe. The twenty-year Mediterranean war, the campaign against the Moriscos of Granada, and then the interconnected military effort in the Netherlands, northern France, and the English Channel drove the crown to search for all possible sources of income. Charles V’s revenues had tripled during his reign, but Philip II’s “doubled in the period 1556–73 alone, and more than redoubled by the end of the reign. ”25

费利普还承继了同法国的战争,而这场战争的花费是如此之大,1557年西班牙王室不得不自行宣布破产,当时,像富杰尔那样的大银行家族也只好屈服。能够聊以自慰的是,同一年,法国也被迫宣告破产,这是1559年双方同意在沙托·坎布雷齐和谈的主要原因。紧接着,费利普马上要对付强大的土耳其敌军,20年的地中海战争,对格林纳达摩尔人的战役,在荷兰、法国北部和英吉利海峡的错综复杂的军事行动逼迫王室寻求一切可能的收入来源。查理五世在位期间赋税增加了2倍,而费利普二世仅在1556—1573年间就增税1倍,到他统治的末年,几乎又翻了一番。

His outgoings, however, were far larger. In the Lepanto campaign (1571), it was reckoned that the maintenance of the Christian fleets and soldiers would cost over 4 million ducats annually, although a fair part of this burden was shared by Venice and the papacy. 26 The payments to the Army of Flanders were already enormous by the 1570s, and nearly always overdue: this in turn provoking the revolts of the troops, particularly after Philip’s 1575 suspension of payments of interest to his Genoese bankers. 27 The much larger flow of income from American mines—around 2 million ducats a year by the 1580s compared with one-tenth of that four decades earlier—rescued the crown’s finances, and credit, temporarily; but the armada of 1588 cost 10 million ducats and its sad fate represented a financial as well as a naval disaster. By 1596, after floating loans at an epic rate, Philip again defaulted. At his death two years later his debts totaled the enormous sum of 100 million ducats, and interest payments on this sum equaled about two-thirds of all revenues. 28 Although peace with France and England soon followed, the war against the Dutch ground away until the truce of 1609, which itself had been precipitated by Spanish army mutinies and a further bankruptcy in 1607.

费利普的开支更大,在勒班陀战役中,据估计维持基督教舰队和士兵的费用每年需要超出400万达卡,虽然威尼斯和教皇分担了一大部分。佛兰德军的费用到16世纪70年代已十分庞大,而且总是不能按期支付,结果激起军队暴动。1557年,费利普停止向热那亚银行家偿还利息后,形势更趋恶化。虽然来自美洲矿产收入的猛增,暂时缓解了王室的财政和信用危机,16世纪80年代,每年约有200万达卡,而大约40年前只有1/10的样子;但是,1588年的无敌舰队的花费竟达1 000万达卡,而它的悲惨命运,不仅仅是一场海军灾难,也是王室财政的灾难。1596年,费利普以空前的额数大借公债之后,再一次拒付。两年后,他去世的时候,总债务高达1亿达卡。这笔巨债的利息差不多等于全部赋税的2/3。尽管西班牙很快与法、英两国达成和议,但与荷兰的战争仍然继续艰苦地进行着,直到1609年,才实现停火,且停火本身也是1607年西班牙兵变并进一步瓦解而紧急促成的。

During the few years of peace which followed, there was no substantial reduction in Spanish governmental expenditures. Quite apart from the massive interest payments, there was still tension in the Mediterranean (necessitating a grandiose scheme for constructing coastal fortifications), and the far-flung Spanish empire was still subject to the depredations of privateers (necessitating considerable defense outlays in the Philippines and the Caribbean as well as on the high seas fleet). 29 The state of armed truce in Europe which existed after 1610 hardly suggested to Spain’s proud leaders that they could reduce arms expenditures. All that the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618 did, therefore, was to convert a cold war into a hot one, and to produce an increased flow of Spanish troops and money into Flanders and Germany. It is interesting to note that the run of early Habsburg victories in Europe and the successful defense of the Americas in this period largely coincided with— and was aided by—significant increases in bullion deliveries from the New World. But by the same token, the reduction in treasure receipts after 1626, the bankruptcy declaration of the following year, and the stupendous Dutch success in seizing the silver fleet in 1628 (costing Spain and its inhabitants as much as 10 million ducats) caused the war effort to peter out for a while. And despite the alliance with the emperor, there was no way (except under Wallenstein’s brief period of control) that German revenues could make up for this Spanish deficiency.

在以后几年的和平时期,西班牙政府的开支没有实质性减少。先暂且不谈巨额利息问题,仅地中海局势的持续紧张,就需要大笔经费以修筑一个沿海防御工事;地域辽阔的西班牙海岸屡遭私掠船的抢劫,也需要在菲律宾、加勒比以及公海舰队上花费相当大的防御费用。1610年以后,欧洲的停火局面并没有使高傲的西班牙领袖们考虑减少军费开支。1618年爆发的三十年战争不过将一场冷战变为热战,使越来越多的西班牙军队和钱财流入佛兰德和德意志。值得注意的是,哈布斯堡家族这一时期在欧洲的最初胜利和在美洲有效的防御,很大程度上与其从新世界运来的金锭、银锭的显著增加相吻合,并受它的支持。但出于同样的原因,1626年以后财政收入减少,翌年宣告破产,1628年荷兰人劫持运银舰队的惊人之举(使西班牙及其居民失去1 000万达卡之多),使得战争努力中止了一段时间。尽管德意志与皇帝结盟,但其收入却绝对难以弥补西班牙的亏空(除去华伦斯坦当权的那段时间)。

This, then, was to be the Spanish pattern for the next thirty years of war. By scraping together fresh loans, imposing new taxes, and utilizing any windfall from the Americas, a major military effort like, say, Cardinal-Infante’s intervention in Germany in 1634–1635 could be supported; but the grinding costs of war always eventually eroded these short-term gains, and within a few more years the financial position was worse than ever. By the 1640s, in the aftermath of the Catalan and Portuguese revolts, and with the American treasure flow much reduced, a long, slow decline was inevitable. 30 What other fate was due to a nation which, although providing formidable fighters, was directed by governments which consistently spent two or three times more than the ordinary revenues provided?

这就是后来30年西班牙应付战争的情形,把新借到的债款凑到一起,加上新税,并利用任何来自美洲的意外收入,就可支持一场重要的军事行动,诸如,茵凡特红衣主教在1634—1635年对德意志的干涉。但是耗竭财力的战争总是最终侵蚀掉这些短期收入,不出几年财政状况就更加恶化。17世纪40年代在加泰罗尼亚人和葡萄牙人的起义之后,来自美洲的财富大大减少,一个长期的、缓慢的衰落已经不可避免。纵使一个国家拥有极好的士兵,一旦由一个支出超出正常收入二三倍的政府来管理,还能指望有什么好结果吗?

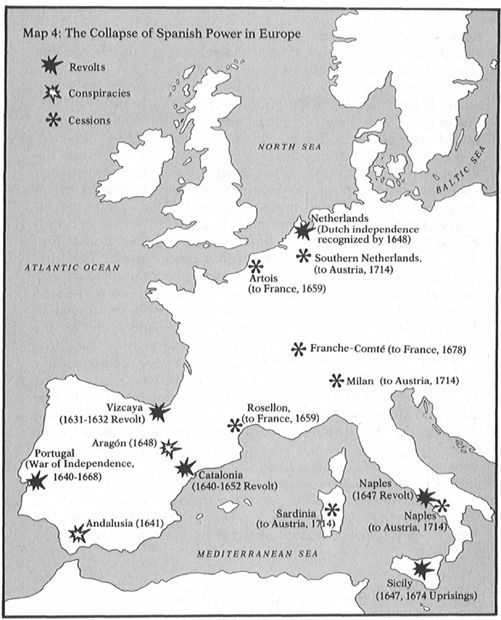

The second chief cause of the Spanish and Austrian failure must be evident from the narrative account given above: the Habsburgs simply had too much to do, too many enemies to fight, too many fronts to defend. The stalwartness of the Spanish troops in battle could not compensate for the fact that these forces had to be dispersed, in homeland garrisons, in North Africa, in Sicily and Italy, and in the New World, as well as in the Netherlands. Like the British Empire three centuries later, the Habsburg bloc was a conglomeration of widely scattered territories, a political-dynastic tour de force which required enormous sustained resources of material and ingenuity to keep going. As such, it provides one of the greatest examples of strategical overstretch in history; for the price of possessing so many territories was the existence of numerous foes, a burden also carried by the contemporaneous Ottoman Empire. 31

西班牙和奥地利失败的第二个主要原因从以上简述中已不难看出:哈布斯堡要管的事太多了,要对付的敌人太多了,要防卫的阵线太多了。虽说西班牙军队在战场上很坚强,但把他们分散到国内守备,分散到北非、西西里、意大利、新大陆和荷兰,就力不从心、难于胜任了。正像3个世纪以后的英帝国一样,哈布斯堡集团把分布广泛的领土糅合在一起,是一个政治王朝的惊人绝技,需要极大的物质来源和心计维持其运转。这种情况是历史上战略过分扩张的最大例证之一;占领广大领土,代价就是树立众多的仇敌,同时代的奥斯曼帝国也背着同样包袱。

Related to this is the very significant issue of the chronology of the Habsburg wars. European conflicts in this period were frequent, to be sure, and their costs were a terrible burden upon all societies. But all the other states—France, England, Sweden, even the Ottoman Empire—enjoyed certain periods of peace and recovery. It was the Habsburg’s, and more especially Spain’s, fate to have to turn immediately from a struggle against one enemy to a new conflict against another; peace with France was succeeded by war with the Turks; a truce in the Mediterranean was followed by extended conflict in the Atlantic, and that by the struggle for northwestern Europe. During some awful periods, imperial Spain was fighting on three fronts simultaneously, and with her enemies consciously aiding each other, diplomatically and commercially if not militarily. 32 In contemporary terms, Spain resembled a large bear in the pit: more powerful than any of the dogs attacking it, but never able to deal with all of its opponents and growing gradually exhausted in the process.

与此相关的是哈布斯堡战争年表这个不容忽视的问题。欧洲冲突频频爆发,其费用对每个社会都是难于承受的负担。但是,所有其他国家,法国、英国、瑞典,甚至奥斯曼帝国,都享有一段和平与恢复的时期。只有哈布斯堡,特别是西班牙,总是不停地从对付一个敌人的斗争转向对付另一个敌人的斗争。刚刚与法国媾和,接着就是同土耳其人交战;地中海停战,接着就是大西洋上的广泛冲突和西北欧战争。在某些困难时期,西班牙帝国同时三面受敌,而敌人即使没有军事援助,也有意识地在外交和商业上相互支援。用当时人的话来说,西班牙像一只掉在坑里的大熊,比任何一条进攻它的狗都强大,然而,它终究敌不过所有的对手,结果在这个过程中逐渐精疲力竭。

Yet how could the Habsburgs escape from this vicious circle? Historians have pointed to the chronic dispersion of energies, and suggested that Charles V and his successors should have formulated a clear set of defense priorities. 33 The implication of this is that some areas were expendable; but which ones?

那么,哈布斯堡如何才能逃脱这种恶性循环呢?历史学家指出了长期分散力量的状况,提出查理五世和他的继承人应制定一套清楚明确的优先防御计划。这就暗示了某些地区是可以放弃的,但是,指的是哪些地区呢?

In retrospect, one can argue that the Austrian Habsburgs, and Ferdinand II in particular, would have been wiser to have refrained from pushing forward with the Counter-Reformation in northern Germany, for that brought heavy losses and few gains. Yet the emperor would still have needed to keep a considerable army in Germany to check princely particularism, French intrigues, and Swedish ambition; and there could also be no reduction in this Habsburg armed strength so long as the Turks stood athwart Hungary, only 150 miles from Vienna. The Spanish government, for its part, could allow the demise of their Austrian cousins neither at the hands of the French and Lutherans nor at the hands of the Turks, because of what it might imply for Spain’s own position in Europe. This calculation, however, did not seem to have applied in reverse. After Charles V’s retirement in 1556 the empire did not usually feel bound to aid Madrid in the latter’s wars in western Europe and overseas; but Spain, conscious of the higher stakes, would commit itself to the empire. 34 The long-term consequences of this disparity of feeling and commitment are interesting. The failure of Habsburg Spain’s European aims by the mid-seventeenth century was clearly related to its internal problems and relative economic decline; having overstrained itself in all directions, it was now weak at heart. In Habsburg Austria’s case, on the other hand, although it failed to defeat Protestantism in Germany, it did achieve a consolidation of powers in the dynastic lands (Austria, Bohemia, and so on)—so much so that on this large territorial base and with the later creation of a professional standing army,35 the Habsburg Empire would be able to reemerge as a European Great Power in the later decades of the seventeenth century, just as Spain was entering a period of even steeper decline. 36 By that stage, however, Austria’s recuperation can hardly have been much of a consolation to the statesmen in Madrid, who felt they had to look elsewhere for allies.

回过头来反思,人们可以说奥地利,特别是斐迪南二世,要是聪明一点就不会随着德意志北部的反改革势力向前推进,因为这样做得不偿失。然而,皇帝硬是要在德意志保留一支强大的军队,以防止王公的派系倾向、法国人的诡计和瑞典人的野心;而且只要土耳其人骄横地站在匈牙利,相距维也纳150英里,哈布斯堡的军队就不能减少。对西班牙政府来说,它不能让奥地利表兄弟落入法国人和路德派手里,也不能让他们落入土耳其人手里,因为这对西班牙自己在欧洲的地位至关重要。不过,奥地利似乎并没有这么想。查理五世在1556年退位后,帝国目睹马德里在西欧和海上作战时,并未感到有义务帮忙;而西班牙意识到这个更高的利益,总是愿为帝国效忠。此种不同感觉和义务所造成的长远结果很有意思。17世纪中叶哈布斯堡西班牙在欧洲的失败与它内部的问题和相对的经济衰退有明显的关系;它在各个方面过于疲劳之后,现在心脏衰弱了。而哈布斯堡的奥地利,虽然没有击退德意志的新教主义,却在王朝土地上(奥地利、波希米亚等)达到一种权力的巩固,在这个广阔的领地上,随着后来建立起一支职业常备军,哈布斯堡家族在17世纪最后几十年有能力再度成为欧洲大国,而此时西班牙的国势却更趋衰微。然而,到了那个阶段,奥地利的元气复苏对马德里的政治家们已谈不上什么安慰了,他们感觉要到别处寻找盟友了。

It is easy to see why the possessions in the New World were an area of vital importance to Spain. For well over a century, they provided that regular addition to Spain’s wealth, and thus to its military power, without which the Habsburg effort could not have been so extensively maintained. Even when the English and Dutch attacks upon the Hispano-Portuguese colonial empire necessitated an everincreasing expenditure on fleets and fortifications overseas, the direct and indirect gains to the Spanish crown from those territories remained considerable. To abandon such assets was unthinkable.

人们很容易看到为什么新世界的领土对西班牙是一个至关重要的地区。在一个多世纪里,它们如期补充西班牙的财富,以及军事力量。没有这些补充,哈布斯堡家族的军事行动就不可能在如此大的范围内继续维持。甚至当英国人和荷兰人进攻西班牙-葡萄牙的殖民帝国,致使海外的舰队和防御工事费用越来越膨胀时,西班牙王室从这些领土获取的直接和间接收益仍然相当可观,放弃这种好处是不可思议的事情。

This left for consideration the Habsburg possessions in Italy and those in Flanders. Of the two, a withdrawal from Italy had less to recommend itself. In the first half of the sixteenth century, the French would have filled the Great Power vacuum there, and used the wealth of Italy for their own purposes—and to Habsburg detriment. In the second half of that century Italy was, quite literally, the outer bulwark of Spain’s own security in the face of Ottoman expansion westward. Quite apart from the blow to Spanish prestige and to the Christian religion which would have accompanied a Turkish assault upon Sicily, Naples, and Rome, the loss of this bulwark would have been a grave strategical setback. Spain would then have had to pour more and more money into coastal fortifications and galley fleets, which in any case were consuming the greater part of the arms budget in the early decades of Philip II’s reign. So it made good military sense to commit these existing forces to the active defense of the central Mediterranean, for that kept the Turkish enemy at a distance; and it had the further advantage that the costs of such campaigning were shared by the Habsburg possessions in Italy, by the papacy, and, on occasions, by Venice. Withdrawal from this front brought no advantages and many potential dangers.

值得考虑的还有哈布斯堡家族在意大利和佛兰德的领地。关于这两个地方,从意大利撤军这件事本身就显得不妙。16世纪前半叶,法国已想到要填补这块霸权真空,攫取意大利的财富为自己的目标服务,这当然要伤害哈布斯堡的利益。在16世纪后半叶,意大利实际上是西班牙抵御奥斯曼向西扩张的屏障。土耳其人对西西里、那不勒斯和罗马的攻击也是对西班牙的威信以及基督教的打击,失去意大利将会是一个战略上的严重倒退,那样一来,西班牙就得把越来越多的金钱用于海岸防御和大帆船舰队的建造上,而这些活动在费利普二世统治下的早期已经占了更大一部分预算。因此,利用现存力量保卫地中海的中段在军事上是合理的,可以拒土耳其敌人于一定距离之外;另一个有利点在于,这场战争的费用将由哈布斯堡在意大利的领地和教皇乃至威尼斯分担。而从这条战线撤退就将无利可图,其潜在危险更不在话下。

By elimination, then, the Netherlands was the only area in which Habsburg losses might be cut; and, after all, the costs of the Army of Flanders in the “Eighty Years War” against the Dutch were, thanks to the difficulties of the terrain and the advances in fortifications,37 quite stupendous and greatly exceeded those on any other front. Even at the height of the Thirty Years War, five or six times as much money was allocated to the Flanders garrison as to forces in Germany. “The war in the Netherlands,” observed one Spanish councillor, “has been the total ruin of this monarchy. ” In fact, between 1566 and 1654 Spain sent at least 218 million ducats to the Military Treasury in the Netherlands, considerably more than the sum total (121 million ducats) of the crown’s receipts from the Indies. 38 Strategically, too, Flanders was much more difficult to defend: the sea route was often at the mercy of the French, the English, and the Dutch—as was most plainly shown when the Dutch admiral Tromp smashed a Spanish fleet carrying troop reinforcements in 1639—but the “Spanish Road” from Lombardy via the Swiss valleys or Savoy and Franche- Comté up the eastern frontiers of France to the lower Rhine also contained a number of very vulnerable choke points. 39 Was it really worthwhile to keep attempting to control a couple of million recalcitrant Netherlanders at the far end of an extensive line of communications, and at such horrendous cost? Why not, as the representatives of the overtaxed Cortes of Castile slyly put it, let the rebels rot in their heresy? Divine punishment was assured them, and Spain would not have to carry the burden any longer. 40

如此权衡以后,尼德兰就是哈布斯堡可以减少损失的唯一地区了,而且归根到底,佛兰德军在对荷兰的“八年战争中的费用支出极其惊人,大大超过了其他任何战线”。这是由于地形复杂、防御工事先进的原故。甚至当“三十年战争”进入高峰期,用在佛兰德驻军身上的金钱,仍相当于德意志驻军的5到6倍。一位西班牙参议员评论说:“荷兰的战争是毁灭这个王国的祸害。”事实上,从1566年到1654年,西班牙至少向荷兰军用财库输送21 800万达卡,这比王室从印度群岛得到的总数12 100万达卡要多得多。从战略上讲,佛兰德的防御也更加困难;海路经常处在法国人、英国人和荷兰人的控制之下,1639年荷兰舰队司令特隆普击溃一支装载增援部队的西班牙舰队就是明证。但是,从伦巴第经瑞士山谷或萨伏依和弗朗什孔泰,北上法国东部边境,到莱茵河下游的这条“西班牙路”,也有几处非常脆弱的咽喉部。难道值得用如此巨大的代价来力图控制处于漫长交通线顶端的两百万顽固的尼德兰人吗?为什么不能像卡斯蒂利亚担负着沉重税务的国会代表们狡猾地指出的那样,让那些反叛者在异教中堕落呢?上帝肯定会惩罚他们,西班牙用不着再担这副担子了。

The reasons given against an imperial retreat from that theater would not have convinced those complaining of the waste of resources, but they have a certain plausibility. In the first place, if Spain no longer possessed Flanders, it would fall either to France or to the United Provinces, thereby enhancing the power and prestige of one of those inveterate Habsburg enemies; the very idea was repellent to the directors of Spanish policy, to whom “reputation” mattered more than anything else. Secondly, there was the argument advanced by Philip IV and his advisers that a confrontation in that region at least took hostile forces away from more sensitive places: “Although the war which we have fought in the Netherlands has exhausted our treasury and forced us into the debts that we have incurred, it has also diverted our enemies in those parts so that, had we not done so, it is certain that we would have had war in Spain or somewhere nearer. ”41 Finally, there was the “domino theory”—if the Netherlands were lost, so also would be the Habsburg cause in Germany, smaller possessions like Franche-Comté, perhaps even Italy. These were, of course, hypothetical arguments; but what is interesting is that the statesmen in Madrid, and their army commanders in Brussels, perceived an interconnected strategical whole, which would be shattered if any one of the parts fell:

尽管反对从那个战区撤出帝国军队的人所提出的理由不足以说服那些埋怨浪费资源的人,但也不乏某些道理。首先,如果西班牙不占领佛兰德,它就会落到法国或联合省手里,从而加强哈布斯堡那两个不共戴天的仇敌的力量和威信;这种念头是西班牙决策者所不能接受的。对他们说来,“威望”比其他任何东西都重要。其二,费利普四世和他的顾问所提出的一个理由是,那个地区的对抗起码能把敌军的力量从敏感地区调开:“虽然我们在尼德兰进行的战争耗尽了我们的国库,迫使我们举债,但也把我们的敌人调到了那些地区,否则,肯定会在西班牙或其他附近地区发生战争。”最后,是“多米诺骨牌理论”,如果丢失尼德兰,那么,哈布斯堡在德意志的利益,弗朗什孔泰这类小领地,甚至于意大利都会相继失去。这当然只是些假设性的理由,有趣的是马德里的政治家和他们在布鲁塞尔的军事指挥官已看到一个相互关联的战略整体,如果其中任何一部分陷落,整体就会随之动摇。

The first and greatest dangers [so the reasoning went in the critical year of 1635] are those that threaten Lombardy, the Netherlands and Germany. A defeat in any of these three is fatal for this Monarchy, so much so that if the defeat in those parts is a great one, the rest of the monarchy will collapse; for Germany will be followed by Italy and the Netherlands, and the Netherlands will be followed by America; and Lombardy will be followed by Naples and Sicily, without the possibility of being able to defend either. 42

首要的危险(在1635年危机中人们这样解释)是来自对伦巴底、尼德兰和德意志的威胁。三处中任何一方的失败都是对王国的致命打击。如果在这些地方的失败是一次大失败,王国的其余部分就会土崩瓦解;因为德意志完了,接着就会是意大利和尼德兰,尼德兰之后就是美洲;伦巴底之后就是那不勒斯和西西里,要想保全哪一方都是不可能的。

In accepting this logic, the Spanish crown had committed itself to a widespread war of attrition, which would last until victory was secured, or a compromise peace was effected, or the entire system was exhausted.

西班牙接受了这个逻辑,把自己拖进一场广泛持久的消耗战,或拖到胜利的到来,或等到和平妥协的实现,或使整个体系衰竭崩溃。

Perhaps it is sufficient to show that the sheer costs of continuous war and the determination not to abandon any of the four major fronts were bound to undermine Spanish-Imperial ambitions in any case. Yet the evidence suggests that there was a third, related cause: namely, that the Spanish government in particular failed to mobilize available resources in the most efficient way and, by acts of economic folly, helped to erode its own power.

不断开战的巨额费用以及不愿放弃四大战场中的任何一方,可能已足以表明西班牙帝国的野心是肯定实现不了的。而且,还有另外一个联系紧密、证据充分的原因:即西班牙政府没有把可利用的资源有效地利用起来,其经济上的愚蠢导致权力的腐败。

Although foreigners frequently regarded the empire of Charles V or that of Philip II as monolithic and disciplined, it was in fact a congeries of territories, each of which possessed its own privileges and was proud of its own distinctiveness. 43 There was no central administration (let alone legislature or judiciary), and the only real connecting link was the monarch himself. The absence of such institutions which might have encouraged a sense of unity, and the fact that the ruler might never visit the country, made it difficult for the king to raise funds in one part of his dominions in order to fight in another. The taxpayers of Sicily and Naples would willingly pay for the construction of a fleet to resist the Turks, but they complained bitterly at the idea of financing the Spanish struggle in the Netherlands; the Portuguese saw the sense of supporting the defense of the New World, but had no enthusiasm for German wars. This intense localism had contributed to, and was reflected by, jealously held fiscal rights. In Sicily, for example, the estates resisted early Habsburg efforts to increase taxation and had risen against the Spanish viceroy in 1516 and 1517; being poor, anarchical, and possessing a parliament, Sicily was highly unlikely to provide much for the general defense of Habsburg interests. 44 In the kingdom of Naples and in the newer acquisition of Milan, there were fewer legislative obstacles to Spanish administrators under pressure from Madrid to find fresh funds. Both therefore could provide considerable financial aid during Charles V’s reign; but in practice the struggle to retain Milan, and the wars against the Turks, meant that this flow was usually reversed. To hold its Mediterranean “bulwark,” Spain had to send millions of ducats to Italy, to add to those raised there. During the Thirty Years War the pattern was reversed again, and Italian taxes helped to pay for the wars in Germany and the Netherlands; but, taking this period 1519–1659 as a whole, it is hard to believe that the Habsburg possessions in Italy contributed substantially more—if at all—to the common fund than they themselves took out for their own defense. 45

外国人通常把查理五世或费利普二世的帝国视为律令严明的整体,然而,事实并非如此,它不过是一片分散的领土,各自都有自己的特权及其引以自豪的特殊性。没有真正的中央管理机构(立法或司法除外),唯一的实际联系是君主本人。这里缺乏一个使人产生整体感的机构,统治者可能从来就没有视察过整个国家,国王很难从他的一部分领土筹款到另一部分去作战。西西里和那不勒斯的纳税人情愿为抵抗土耳其人建立一支舰队,但一想到要用钱支持西班牙在尼德兰的战争就怒气冲天;而葡萄牙人懂得保卫新世界的意义,但对德意志的战争毫无热情。这种强烈的地方主义助长并反映在各地紧抓着自己的财政权上。例如,西西里的领地抵制哈布斯堡家族早期增加赋税的做法,于1516年和1517年起来反抗西班牙总督;西西里既穷又有无政府倾向,并有一个议会,当然不能为哈布斯堡的整体防卫利益作出多大贡献。在那不勒斯王国和新占领的米兰,迫于马德里的压力的西班牙行政官筹集新款项所遇到的立法障碍较少,因此两者都能在查理五世时期提供相当的财政援助,但实际上在为保住米兰而进行的战争和反土耳其的战争中,钱是朝相反方向流去的。西班牙为了守住地中海这个“屏障”,不得不向意大利送去数百万达卡,以补充从当地征得的款项。“三十年战争”期间,这种模式被颠倒过来,意大利纳税人资助在尼德兰和德意志的战争。不过,如果把1519年到1659年作为一个整体来考察,很难相信哈布斯堡家族在意大利的领地对公共基金所作的贡献,会大大超过他们为自己的防御而从公共基金中支出的部分。

The Netherlands became, of course, an even greater drain upon general imperial revenues. In the early part of Charles V’s reign, the States General provided a growing amount of taxes, although always haggling over the amount and insisting upon recognition of their privileges. By the emperor’s later years, the anger at the frequent extraordinary grants which were demanded for wars in Italy and Germany had fused with religious discontents and commercial difficulties to produce a widespread feeling against Spanish rule. By 1565 the state debt of the Low Countries reached 10 million florins, and debt payments plus the costs of normal administration exceeded revenues, so that the deficit had to be made up by Spain. 46 When, after a further decade of mishandling from Madrid, these local resentments burst into open revolt, the Netherlands became a colossal drain upon imperial resources, with the 65,000 or more troops of the Army of Flanders consuming onequarter of the total outgoings of the Spanish government for decade after decade.

尼德兰当然是帝国总收入更大的耗费之地。查理五世统治初期,国会提供的税款不断增加,尽管总要为数字讨价还价,并坚持要承认他们的特权。到了这个皇帝的晚年,他们为在意大利和德意志进行战争而需要频繁地拿出额外款项而愤怒,这与宗教不满情绪和商业上的困难结合起来,产生了普遍的反对西班牙统治的情绪。到1565年,低地国家的国债达1 000万佛罗林,债务加上一般行政费用已超过赋税,于是西班牙就得弥补这个差额。又经过马德里的十年瞎指挥,地方性反感演变成公开暴动,尼德兰成为帝国资源的一大漏洞,6.5万人以上的佛兰德军在一个又一个十年里消耗着西班牙政府总支出的1/4。

But the most disastrous failure to mobilize resources lay in Spain itself, where the crown’s fiscal rights were in fact very limited. The three realms of the crown of Aragon (that is, Aragon, Catalonia, and Valencia) had their own laws and tax systems, which gave them a quite remarkable autonomy. In effect, the only guaranteed revenue for the monarch came from royal properties; additional grants were made rarely and grudgingly. When, for example, a desperate ruler like Philip IV sought in 1640 to make Catalonia pay for the troops sent there to defend the Spanish frontier, all this did was to provoke a lengthy and famous revolt. Portugal, although taken over from 1580 until its own 1640 rebellion, was completely autonomous in fiscal matters and contributed no regular funds to the general Habsburg cause. This left Castile as the real “milch cow” in the Spanish taxation system, although even here the Basque provinces were immune. The landed gentry, strongly represented in the Castilian Cortes, was usually willing to vote taxes from which they were exempt. Furthermore, taxes such as the alcabala (a 10 percent sales tax) and the customs duties, which were the ordinary revenues, together with the servicios (grants by the Cortes), millones (a tax on foodstuffs, also granted by the Cortes), and the various church allocations, which were the main extraordinary revenues, all tended to hit at trade, the exchange of goods, and the poor, thus spreading impoverishment and discontent, and contributing to depopulation (by emigration). 47

但是,在动员资源方面最惨重的失败发生在西班牙本土。那里,王室的财政权实际上极其有限,阿拉贡的三块领地(阿拉贡、卡泰罗尼亚和瓦伦西亚)都有自己的法律和税务制度,拥有相当大的自主权。结果,国王唯一有保障的收入是来自王室的财产,额外的款项既数目微少,又很不情愿。例如,费利普四世这样不顾一切的统治者,在1640年想要卡泰罗尼亚为派到那里保卫西班牙前线的军队拨款时,结果只是引起一场历时经久的著名暴动。葡萄牙虽然从1580年直到1640年起义时期被接管,但在财政上完全自治,从不为哈布斯堡的整个利益提供定期款项。剩下的卡斯提尔是西班牙税务体系中的真正“奶牛”,尽管这里的巴斯克诸省也都是免税的。乡绅们在卡斯提尔议会中拥有强有力的代表,通常很愿意为他们免交的税款投票。况且,1/10的营业税、关税这类正常赋税,加上服务税(议会特批)、食品税(也是议会特批)以及各种教会摊派等(这些都是主要的额外赋税),很容易伤害商业、物品交换和穷人,因而造成普遍贫困化和不满,致使人口下降(通过向国外移民)。

Until the flow of American silver brought massive additional revenues to the Spanish crown (roughly from the 1560s to the late 1630s), the Habsburg war effort principally rested upon the backs of Castilian peasants and merchants; and even at its height, the royal income from sources in the New World was only about onequarter to one-third of that derived from Castile and its six million inhabitants. Unless and until the tax burdens could be shared more equitably within that kingdom and indeed across the entirety of the Habsburg territories, this was virtually bound to be too small a base on which to sustain the staggering military expenditures of the age.

直到美洲白银的流入给西班牙王室带来大量的额外收入之前(大约为16世纪60年代至17世纪30年代后期),哈布斯堡的战争费用主要由卡斯提尔的农民和商人承担;即使是白银流入的高峰期,王室从新世界得到的收入,也只有从卡斯提尔及其600万居民中榨取的1/4到1/3。除非将捐税负担较平均地分摊给整个王国,换言之,就是分摊到哈布斯堡的全部领土,否则,仅靠卡斯提尔来维持那个时代压死人的军事开支,确实是杯水车薪。

What made this inadequacy absolutely certain was the retrograde economic measures attending the exploitation of the Castilian taxpayers. 48 The social ethos of the kingdom had never been very encouraging to trade, but in the early sixteenth century the country was relatively prosperous, boasting a growing population and some significant industries. However, the coming of the Counter-Reformation and of the Habsburgs’ many wars stimulated the religious and military elements in Spanish society while weakening the commercial ones. The economic incentives which existed in this society all suggested the wisdom of acquiring a church benefice or purchasing a patent of minor nobility. There was a chronic lack of skilled craftsmen —for example, in the armaments industry—and mobility of labor and flexibility of practice were obstructed by the guilds. 49 Even the development of agriculture was retarded by the privileges of the Mesta, the famous guild of sheep owners whose stock were permitted to graze widely over the kingdom; with Spain’s population growing in the first half of the sixteenth century, this simply led to an increasing need for imports of grain. Since the Mesta’s payments for these grazing rights went into the royal treasury, and a revocation of this practice would have enraged some of the crown’s strongest supporters, there was no prospect of amending the system. Finally, although there were some notable exceptions—the merchants involved in the wool trade, the financier Simon Ruiz, the region around Seville—the Castilian economy on the whole was also heavily dependent upon imports of foreign manufactures and upon the services provided by non-Spaniards, in particular Genoese, Portuguese, and Flemish entrepreneurs. It was dependent, too, upon the Dutch, even during hostilities; “by 1640 three-quarters of the goods in Spanish ports were delivered in Dutch ships,”50 to the profit of the nation’s greatest foes. Not surprisingly, Spain suffered from a constant trade imbalance, which could be made good only by the re-export of American gold and silver.

在剥削卡斯提尔纳税人时所采用的经济倒退手段,使得这种不合比例的情况更趋严重。这个王国的社会思潮从来就不利于商业,但是在16世纪初期,那里有过相对的经济繁荣、人口增长,并出现一些重要的工业。然而,反宗教改革的到来和哈布斯堡的频繁战争,刺激了西班牙社会的许多军事部门而减弱了商业成分。这个社会存在的经济刺激因素,全都使人感到求一份教会有俸圣职或买一份小贵族的特权是明智的。这里长期缺乏熟练的手工业工人,例如在武器制造业,劳动力的流动和就业的灵活性受到行会的阻碍。甚至农业的发展也受到有名的牧羊主行会,即麦斯塔的特权的妨害,这些人的羊群可以在全国到处放牧。由于16世纪前半叶西班牙人口的增长,导致进口更多的粮食。因为麦斯塔为这些放牧权付出的钱进入王室金库,而要废除这种做法就会激怒王室的一些强有力的支持者,因而没有可能改变这种制度。最后,虽然存在一些显著的例外,如从事羊毛贸易的商人金融家西蒙·鲁伊兹,以及塞维利亚地区,但卡斯提尔的经济整个来说还是大量依靠进口外国工业品,依靠非西班牙人,特别是热那亚、葡萄牙和佛兰德企业家提供的服务。它也依靠荷兰人,即使是在敌对期间:“到1640年,西班牙海港3/4的货物都是荷兰船运来的”,让这个国家的最大敌人占便宜。毫不奇怪,西班牙一直不能维持贸易平衡,唯一的补救办法就是再出口来自美洲的金银。

The horrendous costs of 140 years of war were, therefore, imposed upon a society which was economically ill-equipped to carry them. Unable to raise revenues by the most efficacious means, Habsburg monarchs resorted to a variety of expedients, easy in the short term but disastrous for the long-term good of the country. Taxes were steadily increased by all manner of means, but rarely fell upon the shoulders of those who could bear them most easily, and always tended to hurt commerce. Various privileges, monopolies, and honors were sold off by a government desperate for ready cash. A crude form of deficit financing was evolved, in part by borrowing heavily from the bankers on the credit of future Castilian taxes or American treasure, in part by selling interest-bearing government bonds (juros), which in turn drew in funds that might otherwise have been invested in trade and industry. But the government’s debt policy was always done in a hand-to-mouth fashion, without regard for prudent limitations and without the control which a central bank arguably might have imposed. Even by the later stages of Charles V’s reign, therefore, government revenues had been mortgaged for years in advance; in 1543, 65 percent of ordinary revenue had to be spent paying interest on the juros already issued. The more the crown’s “ordinary” income became alienated, the more desperate was its search for extraordinary revenues and new taxes. The silver coinage, for example, was repeatedly debased with copper vellon. On occasions, the government simply seized incoming American silver destined for private individuals and forced the latter to accept juros in compensation; on other occasions, as has been mentioned above, Spanish kings suspended interest repayments and declared themselves temporarily bankrupt. If this latter action did not always ruin the financial houses themselves, it certainly reduced Madrid’s credit rating for the future.

140年战争造成的可怕巨额费用,就这样强加到一个在经济上无力承担的社会身上。哈布斯堡的君主们没有能力用最有效的方式征集赋税,只得求助于各种权宜之计,这样做短期内方便,对国家的长远利益却极其有害。税额以各种方式不断上升,很少落到那些最容易担负的人的肩上,而总是要伤害商业。一个急于得到现款的政府出售各种特权、专利和荣誉。一种形式简陋的赤字财政发展起来了,一方面以卡斯提尔将来的赋税和美洲财富作抵押,大量向银行家借款;一方面发放带利息的政府债券,这反过来又抽走了可以投入贸易和工业的资金。而政府的债务政策总是采用过一天算一天的方式,从来没有谨慎的限制,也没有一种由中央银行可能施加的控制来制约。甚至在查理五世统治的后期,政府的赋税就已提前多年抵押了;1543年,普通赋税的65%要用来偿付已经发出的债券利息。王室的“正常”收入被转让出去越多,就越要急切地寻找额外收入和新税。例如,银币就一再用铜币维隆来替代,实行贬值。有的时候,政府干脆扣押运给私人的美洲白银,强迫货主接受债券作为补偿。还有些时候,如前所述,西班牙国王们宣布他们自己暂时破产,停止偿付利息。如果说这种行为经常毁掉金融家族本身,那么也肯定降低了马德里将来的信用。

Even if some of the blows which buffeted the Castilian economy in these years were not man-made, their impact was the greater because of human folly. The plagues which depopulated much of the countryside around the beginning of the seventeenth century were unpredictable, but they added to the other causes— extortionate rents, the actions of the Mesta, military service—which were already hurting agriculture. The flow of American silver was bound to cause economic problems (especially price inflation) which no society of the time had the experience to handle, but the conditions prevailing in Spain meant that this phenomenon hurt the productive classes more than the unproductive, that the silver tended to flow swiftly out of Seville into the hands of foreign bankers and military provision merchants, and that these new transatlantic sources of wealth were exploited by the crown in a way which worked against rather than for the creation of “sound finance. ” The flood of precious metals from the Indies, it was said, was to Spain as water on a roof—it poured on and then was drained away.

虽说这些岁月里打击卡斯提尔经济的某些因素不是人为的,它们却因人为的愚蠢而更具破坏力。17世纪初期造成农村人口税减的瘟疫是不可预料的,它们加剧了别的因素——横征暴敛的租税、麦斯塔的所作所为以及军役,这些因素已经侵害了农业。美洲白银的流入肯定会造成经济问题(特别是价格上涨),那时的社会却没有对付这个问题的经验,但西班牙通行的条件意味着这种现象对生产者阶级的危害超过非生产阶级,白银很容易从塞维利亚流出,迅速流入外国银行家和军火商手里,结果,来自大西洋彼岸的新财富在王室手里不是用来造成“稳定的财政”,而是起了反作用。有人说,来自西印度群岛的贵重金属,对西班牙而言,就像水浇在屋顶上,浇上去就流走了。

At the center of the Spanish decline, therefore, was the failure to recognize the importance of preserving the economic underpinnings of a powerful military machine. Time and again the wrong measures were adopted. The expulsion of the Jews, and later the Moriscos; the closing of contacts with foreign universities; the government directive that the Biscayan shipyards should concentrate upon large warships to the near exclusion of smaller, more useful trading vessels; the sale of monopolies which restricted trade; the heavy taxes upon wool exports, which made them uncompetitive in foreign markets; the internal customs barriers between the various Spanish kingdoms, which hurt commerce and drove up prices—these were just some of the ill-considered decisions which, in the long term, seriously affected Spain’s capacity to carry out the great military role which it had allocated to itself in European (and extra-European) affairs. Although the decline of Spanish power did not fully reveal itself until the 1640s, the causes had existed for decades beforehand.

因此,西班牙衰落的核心问题是,没有认识到保存一个强大的军事机器的经济支柱的重要性。一次又一次地采取错误的决策:驱赶犹太人,后来是驱赶摩尔人;中断与外国大学的联系;政府指示比斯开造船厂集中生产大型战船,而几乎完全排斥较小的、更有用途的商船;出卖专利权、限制了贸易;对羊毛出口课以重税,使其在国外市场上失去竞争力;西班牙各王国之间的内部关卡有害于商业,造成物价上涨。所有这一切只是其中一些不明智的决策,这些决策从长远来看,严重影响了西班牙给自己规定的在欧洲(以及欧洲以外)事务中扮演的重要的军事角色的能力。虽然西班牙大国的衰落直到17世纪40年代才充分暴露出来,但其原因早在几十年以前就已存在了。