International Comparisons

三 国际较量

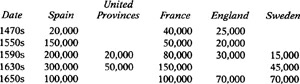

Yet this Habsburg failure, it is important to emphasize, was a relative one. To abandon the story here without examination of the experiences of the other European powers would leave an incomplete analysis. War, as one historian has argued, “was by far the severest test that faced the sixteenth-century state. ”51 The changes in military techniques which permitted the great rise in the size of armies and the almost simultaneous evolution of large-scale naval conflict placed enormous new pressures upon the organized societies of the West. Each belligerent had to learn how to create a satisfactory administrative structure to meet the “military revolution”; and, of equal importance, it also had to devise new means of paying for the spiraling costs of war. The strains which were placed upon the Habsburg rulers and their subjects may, because of the sheer number of years in which their armies were fighting, have been unusual; but, as Table 1 shows, the challenge of supervising and financing bigger military forces was common to all states, many of which seemed to possess far fewer resources than did imperial Spain. How did they meet the test?

强调哈布斯堡的失败是重要的,但这个失败也是相对的。不研究其他欧洲大国的经历而就此驻笔,不能算是全面的分析,正如一位历史学家所论证的,战争“是16世纪国家所面临的最最严峻的考验”。军事技术的变化使得军队大规模扩张,而几乎同时发展起来的大规模的海军冲突,给西方有组织的社会增加了巨大的新压力。每个参战国都要学会怎样组织一个有能力的行政管理机构来对付这场“军事革命”,而且,同样重要的是,要寻求新办法来支付螺旋式上升的战争费用。哈布斯堡统治者及其臣民承受的压力可能是不同寻常的,因为他们的军队作战年头最长;但是,如表1所示,监督和供养大量的武装部队对任何一个国家来说都是一个挑战,它们当中的很多国家看来比西班牙帝国占有的资源要少得多,它们是怎样应付这个考验的呢?

Table 1. Increase in Military Manpower, 1470–166052

表1.1470年—1660年兵力的增长

Omitted from this brief survey is one of the most persistent and threatening foes of the Habsburgs, the Ottoman Empire, chiefly because its strengths and weaknesses were discussed in the previous chapter; but it is worth recalling that many of the problems and deficiencies with which Turkish administrators had to contend— strategical overextension, failure to tap resources efficiently, the crushing of commercial entrepreneurship in the cause of religious orthodoxy or military prestige —appear similar to those which troubled Philip II and his successors. Also omitted will be Russia and Prussia, as nations whose period as great powers in European politics had not yet arrived; and, further, Poland-Lithuania, which despite its territorial extent was too hampered by ethnic diversity and the fetters of feudalism (serfdom, a backward economy, an elective monarchy, “an aristocratic anarchy which was to make it a byword for political ineptitude”53) to commence its own takeoff to becoming a modern nation-state. Instead, the countries to be examined are the “new monarchies” of France, England, and Sweden and the “bourgeois republic” of the United Provinces.

这个简短的概述省略了哈布斯堡家族的最顽强最有威胁性的敌人——奥斯曼帝国,主要是由于它的长处和弱点已在前一章讨论过了。但值得回味的是,土耳其行政官员不得不对付的许多问题和缺陷,看起来类似于费利普二世及其继承人所遇到的,战略扩张过度,未能有效地利用资源,为了宗教的正统或军事威望而压制商人的企业家精神。俄国和普鲁士的状况也被省略了,因为它们成为欧洲政治强国的时代尚未到来。还有波兰-立陶宛,虽然领土广大,但由于民族分散和封建主义的桎梏(农奴制、落后的经济、选举君主制,“一种贵族无政府状况,即俗话所说的政治无能”),妨碍它起步成为现代民族国家。因此,这里要讨论的国家是法国、英国这种“新君主国”,以及瑞典和联合省这个“资产阶级共和国”。

Because France was the state which ultimately replaced Spain as the greatest military power, it has been natural for historians to focus upon the former’s many advantages. It would be wrong, however, to antedate the period of French predominance; throughout most of the years covered in this chapter, France looked —and was—decidedly weaker than its southern neighbor. In the few decades which followed the Hundred Years War, the consolidation of the crown’s territories vis-àvis England, Burgundy, and Britanny, the habit of levying direct taxation (especially the taille, a poll tax), without application to the States General, the steady administrative work of the new secretaries of state, and the existence of a “royal” army with a powerful artillery train made France appear to be a successful, unified, postfeudal monarchy. 54 Yet the very fragility of this structure was soon to be made clear. The Italian wars, besides repeatedly showing how short-lived and disastrous were the French efforts to gain influence in that peninsula (even when allied with Venice or the Turks), were also very expensive: it was not only the Habsburgs but also the French crown which had to declare bankruptcy in the fateful year of 1557. Well before that crash, and despite all the increase in the taille and in indirect taxes like the gabelle and customs, the French monarchy was already resorting to heavy borrowings from financiers at high rates of interest (10–16 percent), and to dubious expedients like selling offices. Worse still, it was in France rather than Spain or England that religious rivalries interacted with the ambitions of the great noble houses to produce a bloody and long-lasting civil war. Far from being a great force in international affairs, France after 1560 threatened to become the new cockpit of Europe, perhaps to be divided permanently along religious borders as was to be the fate of the Netherlands and Germany. 55

因为法国将最终取代西班牙成为最大的军事强国,历史学家们很自然地要强调前者的许多长处。但是,因此而把法国占优势的日期提前就错了;在本章讨论的绝大部分时间里,法国看起来(实际上也如此)比它南边的邻国弱得多。在百年战争后的几十年中,面对英格兰的王室土地——勃艮第和布列塔尼——并入法国,征收直接税(特别是人头税)而不向议会申请的习惯,新国务大臣们的稳妥的行政管理工作,以及拥有一支强大的炮兵辎重队的“王家军队”的存在,都使法兰西似乎要成为一个成功的、统一的、封建后期的王国。然而这个体制的脆弱性很快就清楚了。意大利战争不仅一再显示,法国想在那个半岛争取努力的举动是多么短命和可悲(甚至和威尼斯或土耳其联盟都是如此),付出的代价也极其昂贵:在致命的1557年,不仅哈布斯堡家族,法国王室也宣告破产。早在那次崩溃之前,尽管人头税和间接税如盐税和关税都提高了,法国王室依然从金融家那里以高利(10%—16%)举借重债,而且采取了一些不光彩的权宜之计,如卖官鬻爵。更糟的是,正是在法国,而不是在西班牙或英国,宗教竞争和大贵族的野心相互起作用,造成一场血腥的、长期的内战。1560年以后的法兰西不仅谈不上是一个国际事务中的强国,而且有可能变为欧洲的新斗鸡场,说不定会像尼德兰和德意志那样,按照宗教边界而被永久地分割了。

Only after the accession of Henry of Navarre to the French throne as Henry IV (1589–1610), with his policies of internal compromise and external military actions against Spain, did matters improve; and the peace which he secured with Madrid in 1598 had the great advantage of maintaining France as an independent power. But it was a country severely weakened by civil war, brigandage, high prices, and interrupted trade and agriculture, and its fiscal system was in pieces. In 1596 the national debt was almost 300 million livres, and four-fifths of that year’s revenue of 31 million livres had already been assigned and alienated. 56 For a long time thereafter, France was a recuperating society. Yet its natural resources were, comparatively, immense. Its population of around sixteen million inhabitants was twice that of Spain and four times that of England. While it may not have been as advanced as the Netherlands, northern Italy, and the London region in urbanization, commerce, and finance, its agriculture was diversified and healthy, and the country normally enjoyed a food surplus. The latent wealth of France was clearly demonstrated in the early seventeenth century, when Henry IV’s great minister Sully was supervising the economy and state finances. Apart from the paulette (which was the sale of, and tax on, hereditary offices), Sully introduced no new fiscal devices; what he did do was to overhaul the tax-collecting machinery, flush out thousands of individuals illegally claiming exemption, recover crown lands and income, and renegotiate the interest rates on the national debt. Within a few years after 1600, the state’s budget was in balance. In addition, Sully—anticipating Louis XIV’s minister, Colbert—tried to aid industry and agriculture by various means: reducing the taille, building bridges, roads, and canals to assist the transport of goods, encouraging cloth production, setting up royal factories to produce luxury wares which would replace imports, and so on. Not all of these measures worked to the extent hoped for, but the contrast with Philip III’s Spain was a marked one. 57

只有在纳瓦雷的亨利继承法国王位,成为亨利四世(1589—1610年在位)以后,他的对内妥协、对外以武力反抗西班牙的政策才使情况得以好转。他在1598年与马德里签订的和约非常有利于法国保持为一个独立的国家。但那是一个被内战、盗匪、昂贵的物价、毫无规律的贸易和农业严重削弱的国家,加上其支离破碎的财务制度。1596年国家债务几乎达到3亿里弗尔,那年3 100万里弗尔的赋税有4/5已经派了用场,被事先花出去。因此,在很长一段时间里,法国是一个正在恢复的社会。但是,它的自然资源比较丰富,其人口有1 600万,是西班牙的2倍,英格兰的4倍。虽然在都市化、商业和金融方面比不上尼德兰、北意大利和伦敦地区,但它的农业是多样的、健康的,通常总有剩余食品。法兰西潜在的财富在17世纪初明显地表现出来,那时由亨利四世的得力大臣萨利管理经济和国家财政,萨利除了出卖世袭官爵并向其征税外,没有增加什么新的财务手段;他只是对税收机构进行全面整顿,清除了数千名非法的自称免税的人,恢复王室土地和收入,重新商定国债的利息。1600年以后的几年之内,国家预算已达到平衡,先是萨利,后来则有路易十四的大臣柯尔贝尔想出各种办法支持工业和农业:降低人头税、造桥、修路、开凿运河,以利物资的运输;鼓励纺织工业,建立王室工厂,去生产奢侈品替代进口货等。并非所有这些措施都能满足人们的期望,但比起费利普三世的西班牙却是出色之举。

It is difficult to say whether this work of recovery would have continued had not Henry IV been assassinated in 1610. What was clear was that none of the “new monarchies” could properly function without adequate leadership, and between the time of Henry IV’s death and Richelieu’s consolidation of royal power in the 1630s, the internal politics of France, the disaffection of the Huguenots, and the nobility’s inclination toward intrigue once again weakened the country’s capacity to act as a European Great Power. Furthermore, when France eventually did engage openly in the Thirty Years War it was not, as some historians have tended to portray it, a unified, healthy power but a country still suffering from many of the old ailments. Aristocratic intrigue remained strong and was only to reach its peak in 1648–1653; uprisings by the peasantry, by the unemployed urban workers, and by the Huguenots, together with the obstructionism of local officeholders, all interrupted the proper functioning of government; and the economy, affected by the general population decline, harsher climate, reduced agricultural output, and higher incidence of plagues which seems to have troubled much of Europe at this time,58 was hardly in a position to finance a great war.

很难说,要不是亨利四世在1610年遭到暗杀,这些恢复工作是否还会继续。很明显,这个“新君主国”没有一个能在没有适当的领导的情况下正常运行,从亨利四世之死到17世纪30年代黎塞留巩固王权的这段时间里,法国内部的政治斗争、胡格诺教徒的不满以及贵族的阴谋倾向,再一次削弱了它作为欧洲大国的能力。而且,当法国终于公开加入三十年战争的时候,它并不像某些历史学家描述的那样,是一个统一的、健康的国家,而是一个仍然被老毛病折磨的国家。贵族的阴谋活动仍然很猖狂,在1648—1653年期间达到高潮;农民、城市失业工人以及胡格诺教徒的起义,加上地方官僚对议事进行的阻碍,全都妨害政府机构行使正常职能;人口普遍下降,气候恶化,农业减产,以及那个时期似乎扰乱欧洲许多地方的发生率很高的瘟疫,都影响了它的经济,使之难以支撑一场大的战争。

From 1635 onward, therefore, French taxes had to be increased by a variety of means: the sale of offices was accelerated; and the taille, having been reduced in earlier years, was raised so much that the annual yield from it had doubled by 1643. But even this could not cover the costs of the struggle against the Habsburgs, both the direct military burden of supporting an army of 150,000 men and the subsidies to allies. In 1643, the year of the great French military victory over Spain at Rocroi, government expenditure was almost double its income and Mazarin, Richelieu’s successor, had been reduced to even more desperate sales of government offices and an even stricter control of the taille, both of which were highly unpopular. It was no coincidence that the rebellion of 1648 began with a tax strike against Mazarin’s new fiscal measures, and that such unrest swiftly led to a loss in the government’s credit and to its reluctant declaration of bankruptcy. 59 Consequently, in the eleven years of Franco-Spanish warfare which remained after the general Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the two contestants resembled punchdrunk boxers, clinging to each other in a state of near-exhaustion and unable to finish the other off. Each was suffering from domestic rebellion, widespread impoverishment, and dislike of the war, and was on the brink of financial collapse. It was true that, with generals like d’Enghien and Turenne and military reformers like Le Tellier, the French army was slowly emerging to be the greatest in Europe; but its naval power, built up by Richelieu, had swiftly disintegrated because of the demands of land warfare;60 and the country still needed a solid economic base. In the event, it was France’s good fortune that England, resurgent in its naval and military power under Cromwell, elected to join the conflict, thereby finally tilting the balance against a distressed Spain. The Treaty of the Pyrenees which followed was symbolic less of the greatness of France than of the relative decline of its overstretched southern neighbor, which had fought on with remarkable tenacity. 61

因此,从1635年之后,法国的税收不得不以各种方式增加。官爵出售加快了,早年曾削减的人头税增长到如此之多,以至于到1643年时,年收益已经加倍。即使这样仍不足以弥补反对哈布斯堡的战争费用,直接的军事负担是支持一支15万人的军队,另有给盟国的津贴。1643年是法国在罗克鲁瓦对西班牙战争的大胜之年,政府的开支几乎是收入的两倍,黎塞留的继承人马扎林陷入绝境,只好加紧出售政府官爵,更加严格控制人头税,而这两项政策都很不得人心。1648年的起义从拒绝纳税开始,反对马扎林的新财政措施并非偶然。这类动乱迅速导致政府失去信用和无可奈何地宣布破产。

Consequently, in the eleven years of Franco-Spanish warfare which remained after the general Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the two contestants resembled punchdrunk boxers, clinging to each other in a state of near-exhaustion and unable to finish the other off. Each was suffering from domestic rebellion, widespread impoverishment, and dislike of the war, and was on the brink of financial collapse. It was true that, with generals like d’Enghien and Turenne and military reformers like Le Tellier, the French army was slowly emerging to be the greatest in Europe; but its naval power, built up by Richelieu, had swiftly disintegrated because of the demands of land warfare;60 and the country still needed a solid economic base. In the event, it was France’s good fortune that England, resurgent in its naval and military power under Cromwell, elected to join the conflict, thereby finally tilting the balance against a distressed Spain. The Treaty of the Pyrenees which followed was symbolic less of the greatness of France than of the relative decline of its overstretched southern neighbor, which had fought on with remarkable tenacity. 61

结果,在1648年《威斯特伐利亚和约》以后的法西11年战争中,两个对手就像被打得昏头昏脑的拳击手一样,在几乎耗尽体力的情况下,互相紧紧地抓住对方,而不能将另一方打倒。双方都遭受国内起义、普遍贫困化和厌战情绪的折磨,都处于财政崩溃的边缘。诚然,在东居昂和蒂雷纳这样的将领和勒·泰利埃这样的军事改革家指导下,法国军队逐渐成为欧洲最强大的军队,但是,黎塞留建立的海军由于陆战的需要,很快解体。而这个国家仍需要巩固的经济基础。结果,法国人的好运到来,英国在克伦威尔统治下重振海军和陆军,选择时机加入冲突,终于使天平转向不利于倒霉的西班牙。此后签订的《比利牛斯和约》与其说象征着法兰西的伟大,不如说象征着它那过分扩张的南方邻国的相对衰落,西班牙此时只是在凭借极其顽强的精神而进行战斗了。

In other words, each of the European powers possessed a mixture of strengths and weaknesses, and the real need was to prevent the latter from outweighing the former. This was certainly true of the “flank” powers in the west and north, England and Sweden, whose interventions helped to check Habsburg ambitions on several critical occasions. It was hardly the case, for example, that England stood poised and well prepared for a continental conflict during these 140 years. The key to the English recovery following the Wars of the Roses had been Henry VII’s concentration upon domestic stability and financial prudence, at least after the peace with France in 1492. By cutting down on his own expenses, paying off his debts, and encouraging the wool trade, fishing, and commerce in general, the first Tudor monarch provided a much-needed breathing space for a country hit by civil war and unrest; the natural productivity of agriculture, the flourishing cloth trade to the Low Countries, the increasing use of the rich offshore fishing grounds, and the general bustle of coastal trade did the rest. In the area of national finances, the king’s recovery of crown lands and seizure of those belonging to rebels and rival contenders to the throne, the customs yield from growing trade, and the profits from the Star Chamber and other courts all combined to produce a healthy balance. 62

换句话说,每个欧洲国家都有其优势和弱点,真正需要的是如何防止弱点压倒长处。这点适用于处在西边和北边的“侧翼”国——英国和瑞典,它们的干涉在几个关键时刻有助于打击哈布斯堡的野心。在这140年里,比方说,英国站在那里保持中立,装备好以待大陆上的冲突的情况是几乎没有的。玫瑰战争以后英国元气恢复的关键在于,亨利七世着力于国内稳定和紧缩财政开支,至少是在1492年与法国达成和议后,都铎王朝的第一位君主削减自己的开销,还清债务,鼓励羊毛贸易和渔业,普遍地鼓励商业,为这个饱受内战和动乱之苦的国家提供了一个急需的休养生息的空间;农业的自然高产,与低地国家进行的繁荣的布匹贸易,扩大利用富饶的沿海渔场,热闹不凡的沿海贸易都起了作用。在国家财政方面,这位国王收复王室土地,接管原属于反叛者和王位竞争者的财产,与贸易繁荣带来的关税收入,以及星法院[3]和其他法院的收益合在一起,造成一个健康的入超。

But political and fiscal stability did not necessarily equal power. Compared with the far greater populations of France and Spain, the three to four million inhabitants of England and Wales did not seem much. The country’s financial institutions and commercial infrastructures were crude, compared with those in Italy, southern Germany, and the Low Countries, although considerable industrial growth was to occur in the course of the “Tudor century. ”63 At the military level, the gap was much wider. Once he was secure upon the throne, Henry VII had dissolved much of his own army and forbade (with a few exceptions) the private armies of the great magnates; apart from the “Yeomen of the Guard” and certain garrison troops, there was no regular standing army in England during this period when Franco-Habsburg wars in Italy were changing the nature and dimensions of military conflict. Consequently, such forces as did exist under the early Tudors were still equipped with traditional weapons (longbow, bill) and raised in the traditional way (county militia, volunteer “companies,” and so on). However, this backwardness did not keep his successor, Henry VIII, from campaigning against the Scots or even deter his interventions of 1513 and 1522–1523 against France, since the English king could hire large numbers of “modern” troops—pikemen, arquebusiers, heavy cavalry— from Germany. 64

但是政治和财政稳定并不就等于拥有权力。比起法国和西班牙的众多人口,英格兰和威尔士的300万—400万居民并不算多。这个国家的财政机构和商业基础设施,比起意大利、德意志南部以及低地国家还很粗糙,尽管在都铎世纪里工业有相当的发展。在军事水平上,差距就大多了。一旦亨利七世坐稳王位,他就解散了自己的军队,并禁止大权贵的私人军队(除少数例外);正当法国和哈布斯堡家族在意大利改变军事冲突的性质和规模的时期,英国除了“国王卫队”和某些守备部队以外,没有正规的常备军。结果,都铎王朝初期的武装力量仍沿用传统武器(大弓、长柄矛)装备,用传统方式征集(郡民兵、志愿“联队”等等)。然而,这种落后状况并不能阻止他的继承人亨利八世对苏格兰人发动战争,或妨碍他在1513年和1522—1523年对法国进行干涉,因为英国国王可以从德意志雇佣大量“现代”军队——枪兵、火绳钩枪兵和重骑兵。

If neither these early English operations in France nor the two later invasions in 1528 and 1544 ended in military disaster—if, indeed, they often forced the French monarch to buy off the troublesome English raiders—they certainly had devastating financial consequences. Of the total expenditures of £700,000 by the Treasury of the Chamber in 1513, for example, £632,000 was allocated toward soldiers’ pay, ordnance, warships, and other military outgoings. * Soon, Henry VII’s accumulated reserves were all spent by his ambitious heir, and Henry VIII’s chief minister, Wolsey, was provoking widespread complaints by his efforts to gain money from forced loans, “benevolences,” and other arbitrary means. Only with Thomas Cromwell’s assault upon church lands in the 1530s was the financial position eased; in fact, the English Reformation doubled the royal revenues and permitted largescale spending upon defensive military projects—fortresses along the Channel coast and Scottish border, new and powerful warships for the Royal Navy, the suppression of rebellions in Ireland. But the disastrous wars against France and Scotland in the 1540s cost an enormous £2,135,000, which was about ten times the normal income of the crown. This forced the king’s ministers into the most desperate of expedients: the sale of religious properties at low rates, the seizure of the estates of nobles on trumped-up charges, repeated forced loans, the great debasement of the coinage, and finally the recourse to the Fuggers and other foreign bankers. 65 Settling England’s differences with France in 1550 was thus a welcome relief to a nearbankrupt government.

虽说这两次早期在法国的军事行动以及后来在1528年和1544年的英国入侵没有以军事惨剧告终,虽说他们真的经常迫使法国君主收买这些捣乱的英国进攻者,但这些军事行动确实造成灾难性的财政后果。1513年在内阁财政部70万英镑的总支出中,有63.2万英镑用来支付士兵薪饷、军需、战船和其他军事费用。[4]亨利七世积累的库存很快就被他那野心勃勃的后代花掉了。亨利八世的首相沃尔西因采取强迫借债、“王税”以及其他武断方式筹款而引起普遍不满。只是16世纪30年代托玛斯·克伦威尔夺取教会地产才使财政情况缓和;实际上,英国宗教改革使王室收入加倍,使大规模军事防卫项目的建设成为可能,如沿英吉利海峡和苏格兰边境的要塞、皇家海军新造的大军舰、对爱尔兰起义的镇压等。但是,16世纪40年代对法国、对苏格兰的灾难性战争用掉了213.5万英镑,约为王室正常收入的10倍。这就迫使国王的大臣们采用最不择手段的权宜之计:低价出售宗教财产,捏造罪名没收贵族产业,一再强行借债,货币大贬值,最后是求助于富杰尔斯和其他外国银行家。1550年同法国和解也就成了一个濒于破产的政府的救急良方。

What this all indicated, therefore, was the very real limits upon England’s power in the first half of the sixteenth century. It was a centralized and relatively homogeneous state, although much less so in the border areas and in Ireland, which could always distract royal resources and attention. Thanks chiefly to the interest of Henry VIII, it was defensively strong, with some modern forts, artillery, dockyards, a considerable armaments industry, and a well-equipped navy. But it was militarily backward in the quality of its army, and its finances could not fund a large-scale war. When Elizabeth I became monarch in 1558, she was prudent enough to recognize these limitations and to achieve her ends without breaching them. In the dangerous post-1570 years, when the Counter-Reformation was at its height and Spanish troops were active in the Netherlands, this was a difficult task to fulfill. Since her country was no match for any of the real “superpowers” of Europe, Elizabeth sought to maintain England’s independence by diplomacy and, even when Anglo-Spanish relations worsened, to allow the “cold war” against Philip II to be conducted at sea, which was at least economical and occasionally profitable. 66 Although needing to provide monies to secure her Scottish and Irish flanks and to give aid to the Dutch rebels in the late 1570s, Elizabeth and her ministers succeeded in building up a healthy surplus during the first twenty-five years of her reign— which was just as well, since the queen sorely needed a “war chest” once the decision was taken in 1585 to dispatch an expeditionary force under Leicester to the Netherlands.

这一切都表明,16世纪前半叶的英国实力非常有限。它是一个相对单一的中央集权国家,虽然在边境地区和爱尔兰差得多,并常有可能把王室的资源和注意力吸引去。主要出于亨利八世的兴趣,英国在防御方面很强,拥有一些现代堡垒、炮兵、船坞、相当可观的军火工业,以及一支装备精良的海军。不过,陆军的质量不高,又受财政限制,不可能进行一场大战。当伊丽莎白一世在1558年登上王位时,她的谨慎足以使她认识到这些局限性,并在不超过这些限度的情形下达到她的目的。在1570年以后的危险年代,当反宗教改革达到高峰,西班牙军队活跃在尼德兰时,这是一个难以实现的任务。因为伊丽莎白的国家不是任何一个真正的欧洲“超级大国”的对手,她想办法通过外交保持英国的独立,甚至当英西关系恶化时,她将对付费利普二世的“冷战”施行于海上,这样做至少是便宜的,偶尔还可得利。虽然需要为保住苏格兰和爱尔兰两翼提供款项,在16世纪70年代需要支援荷兰起义者,伊丽莎白和她的大臣们还是在她执政的前25年成功地积累了一笔相当可观的余款,这笔款项的积累恰逢时机,当1585年决定派遣一支由莱斯特指挥的远征军去尼德兰时,这位女王需要的正是一笔“战争基金”。

The post-1585 conflict with Spain placed both strategical and financial demands upon Elizabeth’s government. In considering the strategy which England should best employ, naval leaders like Hawkins, Raleigh, Drake, and others urged upon the queen a policy of intercepting the Spanish silver trade, raiding the enemy’s coasts and colonies, and in general exploiting the advantages of sea power to wage war on the cheap—an attractive proposition in theory, although often difficult to implement in practice. But there was also the need to send troops to the Netherlands and northern France to assist those fighting the Spanish army—a strategy adopted not out of any great love of Dutch rebels or the French Protestants but simply because, as Elizabeth argued, “whenever the last day of France came it would also be the eve of the destruction of England. ”67 It was therefore vital to preserve the European balance, if need be by active intervention; and this “continental commitment” continued until the early seventeenth century, at least in a personal form, for many English troops stayed on when the expeditionary force was merged into the army of the United Provinces in 1594.

1585年以后与西班牙的冲突,给伊丽莎白政府加上战略和财政的双重负担。海军领袖如霍金斯、雷利和德雷克等人,在考虑英国应采取的最佳战略时,敦促女王采用拦截西班牙的白银贸易的政策,进攻敌人的沿海和殖民地。总之,就是利用海上优势打一场实惠的战争——这是一个在理论上很诱人的建议,虽然在实践中很难实行,但是还需要将部队送到尼德兰和法国北部去,以援助那些同西班牙军队作战的部队。采用这个战略并非出于热爱荷兰反抗者或者法国新教徒,其唯一的原因,正如伊丽莎白所解释的:“法国末日到来之时,亦正是英国行将灭亡之日”,因而保持欧洲“均势”至关重要,必要的话就进行实际干涉;这种“对大陆的义务”持续到17世纪初,至少是以个人的形式,因为当远征部队在1594年并入联合省的军队时,很多英国部队留了下来。

In performing the twin function of checking Philip II’s designs on land and harassing his empire at sea, the English made their own contribution to the maintenance of Europe’s political plurality. But the strain of supporting 8,000 men abroad was immense. In 1586 monies sent to the Netherlands totaled over £100,000, in 1587 £175,000, each being about half of the entire outgoings for the year; in the Armada year, allocations to the fleet exceeded £150,000. Consequently, Elizabeth’s annual expenditures in the late 1580s were between two and three times those of the early 1580s. During the next decade the crown spent over £350,000 each year, and the Irish campaign brought the annual average to over £500,000 in the queen’s last four years. 68 Try as it might to raise funds from other sources—such as the selling of crown lands, and of monopolies—the government had no alternative but to summon the Commons on repeated occasions and plead for extra grants. That these (totaling some £2 million) were given, and that the English government neither declared itself bankrupt nor failed to pay its troops, was testimony to the skill and prudence of the monarch and her councillors; but the war years had tested the entire system, left debts to the first Stuart king, and placed him and his successor in a position of dependence upon a mistrustful Commons and a cautious London money market. 69

英国一方面在陆地上阻碍费利普二世的计划,一方面在海上干扰他的帝国,这种双重作用为维持欧洲政治的多元化作出了自己的贡献。但支持8 000人在海外作战是个很大的压力。1586年送往尼德兰的经费总数超过10万英镑,1587年为17.5万英镑,每年相当于当年总支出的一半;西班牙无敌舰队进攻那年,给英国舰队的拨款超过15万英镑。结果,伊丽莎白的年度支出在16世纪80年代末期相当于初期的二三倍。在下一个十年里,王室每年耗费35万英镑以上,女王统治的最后4年里,爱尔兰战争将每年平均支出提到50万英镑以上。政府想尽一切办法从其他来源筹款,如拍卖王室地产、出卖专利,但还是无济于事,只得一再召集下议院开会,请求额外拨款。总共200万英镑左右的款子终于批拨出来,英国政府既没有宣布破产,也没有拒付军队的薪饷,足以证明这位君主和她的大臣们的技巧与谨慎。战争年代考验了这整个制度,给第一位斯图亚特王朝的国王留下债务,使他和他的继承者处于依赖一个不信任的下议院和一个提心吊胆的伦敦金融市场的地位。

There is no space in this story to examine the spiraling conflict between crown and Parliament which was to dominate English politics for the four decades after 1603, in which finance was to play the central part. 70 The inept and occasional interventions by English forces in the great European struggle during the 1620s, although very expensive to mount, had little effect upon the course of the Thirty Years War. The population, trade, overseas colonies, and general wealth of England grew in this period, but none of this could provide a sure basis for state power without domestic harmony; indeed, the quarrels over such taxes as Ship Money— which in theory could have enhanced the nation’s armed strength—were soon to lead crown and Parliament into a civil war which would cripple England as a factor in European politics for much of the 1640s. When England did reemerge, it was to challenge the Dutch in a fierce commercial war (1652–1654), which, whatever the aims of each belligerent, had little to do with the general European balance.

这里没有篇幅探讨王室和议会之间越来越深刻的冲突,这个冲突在1603年以后的40年里居英国政治的统治地位,而财政又是冲突中心。英国军队在17世纪20年代对欧洲大战的不适当的、偶尔的干涉虽然花钱不少,对三十年战争的进程却影响甚微。在此期间,英国的贸易、人口、海外殖民地和一般的财富都增长了,但没有国内的和谐,上述条件都不能为国家权力提供一个坚固的基础;实际上,关于“船款”税这类在理论上可以加强国家武装力量的争吵,很快导致了王室同议会的一场内战,必将削弱英国在17世纪40年代的大部分时间里对欧洲政治的作用。当英国重新出现的时候,是在一场激烈的贸易战中向荷兰人挑战(1652—1654年),这里不管交战者的目标何在,对整个欧洲均势的作用不大。

Cromwell’s England of the 1650s could, however, play a Great Power role more successfully than any previous government. His New Model Army, which emerged from the civil war, had at last closed the gap that traditionally existed between English troops and their European counterparts. Organized and trained on modern lines established by Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus, hardened by years of conflict, well disciplined, and (usually) paid regularly, the English army could be thrown into the European balance with some effect, as was evident in its defeat of Spanish forces at the battle of the Dunes in 1658. Furthermore, the Commonwealth navy was, if anything, even more advanced for the age. Favored by the Commons because it had generally declared against Charles I during the civil war, the fleet underwent a renaissance in the late 1640s: its size was more than doubled from thirty-nine vessels (1649) to eighty (1651), wages and conditions were improved, dockyard and logistical support were bettered, and the funds for all this regularly voted by a House of Commons which believed that profit and power went hand in hand. 71 This was just as well, because in its first war against the Dutch the navy was taking on an equally formidable force commanded by leaders—Tromp and de Ruyter—who were as good as Blake and Monk. When the service was unleashed upon the Spanish Empire after 1655, it was not surprising that it scored successes: taking Acadia (Nova Scotia) and, after a fiasco at Hispaniola, Jamaica; seizing part of the Spanish treasure fleet in 1656; blockading Cádiz and destroying the flota in Santa Cruz in 1657.

克伦威尔的英国在17世纪50年代有可能比任何前一届政府更为成功地扮演了大国角色,从内战中产生的新军,终于消除了英国军队和它的欧洲伙伴之间存在的传统差距。按照拿骚的莫里斯和古斯塔夫·阿道弗斯方式建立的、以现代方法组织和训练出来的英国军队,经过多年战争磨炼,纪律严明,(一般)按期领饷,能够对欧洲的均势发生作用,这已为1658年在迪讷战场上击败西班牙军队所证实。不仅如此,共和国的海军在那个时代更为先进。下议院宠爱它,因为它在内战中一般是宣布反对查理一世的。舰队在17世纪40年代后期经历了一场更新,规模扩大一倍多,从39艘战舰(1649年)增到80艘(1651年),工资和条件改善了,船坞和后勤支援改进了,所有这些款项都由一个深信利益和权力是同步的下议院按期投票批准。这也正恰到好处,因为海军在对荷兰的第一战中就碰上同样的劲旅——指挥官特隆普和德·吕伊特,是同布莱克和基克一样出色的将领。当1655年以后对西班牙帝国进行作战时,无怪乎战果累累:占领阿卡迪亚(新斯科舍),在伊斯帕尼奥拉一场惨败后占领牙买加,1656年夺取西班牙的部分财宝舰队,1657年封锁加的斯并在圣克鲁斯消灭西班牙舰队。

Yet, while these English actions finally tilted the balance and forced Spain to end its war with France in 1659, this was not achieved without domestic strains. The profitable Spanish trade was lost to the neutral Dutch in these years after 1655, and enemy privateers reaped a rich harvest of English merchant ships along the Atlantic and Mediterranean routes. Above all, paying for an army of up to 70,000 men and a large navy was a costly business; one estimate suggests that out of a total government expenditure of £2,878,000 in 1657, over £1,900,000 went on the army and £742,000 on the navy. 72 Taxes were imposed, and efficiently extorted, at an unprecedented level, yet they were never enough for a government which was spending “four times as much as had been thought intolerable under Charles I” before the English Revolution. 73 Debts steadily rose, and the pay of soldiers and sailors was in arrears. These few years of the Spanish war undoubtedly increased the public dislike of Cromwell’s rule and caused the majority of the merchant classes to plead for peace. It was scarcely the case, of course, that England was altogether ruined by this conflict—although it no doubt would have been had it engaged in Great Power struggles as long as Spain. The growth of England’s inland and overseas commerce, plus the profits from the colonies and shipping, were starting to provide a solid economic foundation upon which governments in London could rely in the event of another war; and precisely because England—together with the United Provinces of the Netherlands—had developed an efficient market economy, it achieved the rare feat of combining a rising standard of living with a growing population. 74 Yet it still remained vital to preserve the proper balance between the country’s military and naval effort on the one hand and the encouragement of the national wealth on the other; by the end of the Protectorate, that balance had become a little too precarious.

英国军队终于打破平衡,迫使西班牙在1659年结束同法国的战争,但这个成就并非没有国内的压力。在1655年以后的岁月里,有利可图的西班牙贸易让给了中立的荷兰人,敌人的私掠船沿着大西洋和地中海航线掠夺了不少英国商船。最重要的是,负担一支多至7万人的陆军和庞大的海军是耗资巨大的;有一种估计认为,1657年英国政府支出的287.8万英镑中,有190万镑用于陆军,74.2万镑用于海军。捐税制定了,在史无前例的水平上有效地征收着,但对于一个花费“相当于查理一世时代的4倍”的政府还是不够,而在英国革命以前的查理一世在位时的支出“就被认为令人难以容忍了”。债务不断增加,士兵和水手的薪饷推迟发放。西班牙战争这几年无疑增加了公众对克伦威尔统治的不满,使得大多数商人阶级恳求和平。当然,英国并没有被这场冲突完全摧毁,要是它像西班牙那样长期地争夺大国霸权,那肯定就会毁灭了。英国内陆和海外贸易的发展,加上来自殖民地和航运的利润,开始造就一个坚固的经济基础,使伦敦政府在将来发生战争的情况下可以依赖。确切地说,因为英国和尼德兰联合省已经建立了有效的市场经济,所以在把生活水平提高和人口增长结合起来的方面取得了少有的成就。但是,在国家的军事努力同鼓励国民财富增长这二者之间保持平衡,仍然是至关重要的。在护国时期结束的时候,这个平衡变得太脆弱了。

This crucial lesson in statecraft emerges the more clearly if one compares England’s rise with that of the other “flank” power, Sweden. 75 Throughout the sixteenth century, the prospects for the northern kingdom looked poor. Hemmed in by Lübeck and (especially) by Denmark from free egress to western Europe, engaged in a succession of struggles on its eastern flank with Russia, and repeatedly distracted by its relationship with Poland, Sweden had enough to do simply to maintain itself; indeed, its severe defeat by Denmark in the war of 1611–1613 hinted that decline rather than expansion would be the country’s fate. In addition, it had suffered from internal fissures, which were constitutional rather than religious, and had resulted in confirming the extensive privileges of the nobility. But Sweden’s greatest weakness was its economic base. Much of its extensive territory was Arctic waste, or forest. The scattered peasantry, largely self-sufficient, formed 95 percent of a total population of some 900,000; with Finland, about a million and a quarter— less than many of the Italian states. There were few towns and little industry; a “middle class” was hardly to be detected; and the barter of goods and services was still the major form of exchange. Militarily and economically, therefore, Sweden was a mere pigmy when the youthful Gustavus Adolphus succeeded to the throne in 1611.

如果我们把英国的兴起与另一个“侧翼”国瑞典相比较,在国家管理方面的这个严重教训就更清楚了。在整个16世纪,这个北方王国的形势都不太妙。吕卑克和(特别是)丹麦挡住了它自由进入西欧的通道,东侧不断地同俄国发生战争,与波兰的关系也一再分散注意力,瑞典要维持生存已够忙的了;在1611—1613年的战争中惨败于丹麦,预示着这个国家的命运是衰落而不是扩张,而且还将遭遇内部分裂之苦。这种分裂是立宪性的而不是宗教性的,结果是肯定了贵族的广泛特权。但是瑞典最大的弱点是它的经济基础。它的广大领土多是北极圈内的荒地和森林。分散的农民大多自给自足,占它90万人口的95%;加上芬兰,大约有125万人,比许多意大利的城市国家都要小。城镇和工业太少了,“中产阶级”简直谈不上,以物易物和提供劳务仍是主要的交换形式。因此,年轻的古斯塔夫·阿道弗斯在1611年登上王位时,瑞典在军事上和经济上只不过是一个侏儒。

Two factors, one external, one internal, aided Sweden’s swift growth from these unpromising foundations. The first was foreign entrepreneurs, in particular the Dutch but also Germans and Walloons, for whom Sweden was a promising “undeveloped” land, rich in raw materials such as timber and iron and copper ores. The most famous of these foreign entrepreneurs, Louis de Geer, not only sold finished products to the Swedes and bought the raw ores from them; he also, over time, created timber mills, foundries, and factories, made loans to the king, and drew Sweden into the mercantile “world system” based chiefly upon Amsterdam. Soon the country became the greatest producer of iron and copper in Europe, and these exports brought in the foreign currency which would soon help to pay for the armed forces. In addition, Sweden became self-sufficient in armaments, a rare feat, thanks again to foreign investment and expertise. 76

两个因素——一个外部的、一个内部的,促使瑞典从这个不景气的基础上迅速成长起来。首要的因素是外国企业家,特别是荷兰人,但也有德意志人和华隆人[5],在他们看来,瑞典是一个有前途的“未发展”国家,有丰富的原料如木材、铁矿和铜矿。这些外国企业家中最有名的是路易·德·吉尔,他不仅卖给瑞典人成品和买走矿石,而且时间长了,还建立了木材厂、铸造厂和工厂,向国王贷款,把瑞典人拉进主要以阿姆斯特丹为基地的商业“世界体系”。这个国家很快就变成了欧洲最大的铁和铜的生产地,而这些东西的出口又带进大量外汇,很快就有助于建设武装部队。而且瑞典在军备上也变得自给自足,这种少有的特长还得感谢外国的投资和技术。

The internal factor was the well-known series of reforms instituted by Gustavus Adolphus and his aides. The courts, the treasury, the tax system, the central administration of the chancery, and education were but some of the areas made more efficient and productive in this period. The nobility was led away from faction into state service. Religious solidarity was assured. Local as well as central government seemed to work. On these firm foundations, Gustavus could build a Swedish navy so as to protect the coasts from Danish and Polish rivals and to ensure the safe passage of Swedish troops across the Baltic. Above all, however, the king’s fame rested upon his great military reforms: in developing the national standing army based upon a form of conscription, in training his troops in new battlefield tactics, in his improvements of the cavalry and introduction of mobile, light artillery, and finally in the discipline and high morale which his leadership gave to the army, Gustavus had at his command perhaps the best fighting force in the world when he moved into northern Germany to aid the Protestant cause during the summer of 1630. 77

内部因素就是古斯塔夫及其助手实行的一系列有名的改革。法庭、国库、税收制度、中央管理最高法院以及教育,都是在这个时期变成有效率、有成果的领域,而且这还只是其中的一部分。他把贵族从派系斗争中引开,让他们为国家服务。宗教团结巩固了。地方和中央政府看起来都在发挥职能。在这些坚实的基础上,古斯塔夫可以建立一支瑞典海军用来保护海岸线不受丹麦人和波兰敌手的侵犯,保证瑞典军队安全通过波罗的海。最重要的是,这位国王的名声来自他的军事改革;他以征兵制为基础发展了国家常备军,用新式战术训练部队,改进骑兵,引进机动的轻炮兵,最后,他的指导给部队带来纪律和高昂的士气。当古斯塔夫在1630年夏天开进德意志北部去支援新教运动时,他指挥的可能是世界上最好的战斗部队。

Such advantages were all necessary, since the dimensions of the European conflict were far larger, and the costs far heavier, than anything experienced in the earlier local wars against Sweden’s neighbors. By the end of 1630 Gustavus commanded over 42,000 men; twelve months later, double that number; and just before the fateful battle of Lützen, his force had swollen to almost 150,000. While Swedish troops formed a corps d’élite in all the major battles and were also used to garrison strategic strongpoints, they were insufficient in number to form an army of that size; indeed, four-fifths of that “Swedish” army of 150,000 consisted of foreign mercenaries, Scots, English, and Germans, who were fearfully expensive. Even the struggles against Poland in the 1620s had strained Swedish public finance, but the German war threatened to be far more costly. Remarkably, however, the Swedes managed to make others pay for it. The foreign subsidies, particularly those paid by France, are well known but they covered only a fraction of the costs. The real source was Germany itself: the various princely states, and the free cities, were required to contribute to the cause, if they were friendly; if they were hostile, they had to pay ransoms to avoid plunder. In addition, this vast Swedish-controlled army exacted quarter, food, and fodder from the territories on which it was encamped. To be sure, this system had already been perfected by the emperor’s lieutenant, Wallenstein, whose policy of exacting “contributions” had financed an imperial army of over 100,000 men;78 but the point here is that it was not the Swedes who paid for the great force which helped to check the Habsburgs from 1630 until 1648. In the very month of the Peace of Westphalia itself, the Swedish army was looting in Bohemia; and it was entirely appropriate that it withdrew only upon the payment of a large “compensation. ”

这种优势是完全必要的,因为欧洲战争比起瑞典早期经历过的任何一场对邻国的地区性战争,规模都大得多,代价也大得多。到1630年底,古斯塔夫指挥着一支4.2万人的军队;12个月以后,那个数字翻了一番;在决定命运的吕岑战役之前,他的军队膨胀到15万人。瑞典军队在主要战斗中构成精锐部队,也用来把守战略要地,但没有足够的人力组成那样庞大的军队;实际上,那15万的“瑞典军队”中有4/5是外国雇佣军,苏格兰人、英国人、德意志人,他们的花费是极其昂贵的。早在17世纪20年代对波兰的战争就使瑞典的国家财政感到紧张,而德意志的战争更加费钱。然而瑞典人却出色地想出办法让别人为战争付钱。外国人的资助,特别是法国人的资助是人人皆知的,但那只能补偿一小部分开销。真正的来源是德意志本身;各个公国和自由城市如果是盟友就要资助这一事业;如果是敌对的就得拿出赎金,以避免抢劫。另外,这支由瑞典人控制的庞大军队从他们驻扎的领土上索取驻地、食品和饲料。其实这个制度已由皇帝的助手华伦斯坦完善了,他的索取“资助”的政策养活了一支10万人以上的帝国军队。但这里的关键是,并不是瑞典人出钱在1630年到1648年这一时期用这支大军帮助打击哈布斯堡家族。就在威斯特伐利亚议和谈判的那个月,瑞典军队还在抢掠波希米亚;而它要求一大笔“赔款”才肯撤兵,也是完全正当的。

Although this was a remarkable achievement by the Swedes, in many ways it gave a false picture of the country’s real standing in Europe. Its formidable war machine had been to a large degree parasitic; the Swedish army in Germany had to plunder in order to live—otherwise the troops mutinied, which hurt the Germans more. Naturally, the Swedes themselves had had to pay for their navy, for home defenses, and for forces employed elsewhere than in Germany; and, as in all other states, this had strained governmental finances, which led to desperate sales of crown lands and revenues to the nobility, thus reducing long-term income. The Thirty Years War had also taken a heavy toll in human life, and the extraordinary taxes burdened the peasantry. Furthermore, Sweden’s military successes had given it a variety of trans- Baltic possessions—Estonia, Livonia, Bremen, most of Pomerania—which admittedly brought commercial and fiscal benefits, but the costs of maintaining them in peacetime or defending them in wartime from jealous rivals was to bring a far higher charge upon the Swedish state than had the great campaigning across Germany in the 1630s and 1640s.

虽然这是瑞典人的一个惊人成就,但它在很多方面使人对瑞典在欧洲的地位有一种幻觉。它的强大的战争机器在很大程度上是寄生性的。瑞典军队要在德意志活下去必须抢劫,否则部队就会哗变,那对德意志更有害。当然,瑞典人要自己花钱供养海军,保持国内防御,支持德意志以外的其他地区的军队;像其他国家一样,它消耗了政府的财政,导致不顾一切地向贵族出售王室土地和赋税,因而减少了长期的收入。“三十年战争”也夺走了很多人的生命,极其沉重的税收压在农民身上。加之,瑞典的军事胜利给它带来好几块波罗的海对岸的领地——爱沙尼亚、利沃尼亚、不来梅、大部分波美拉尼亚——应当承认它们带来商业和金融上的利益,但是在和平时期维持它们,在战时保卫它们免入嫉妒的敌人之手,这样给瑞典政府造成的费用大大超过17世纪30年代和40年代在德意志进行的大规模战争。

Sweden was to remain a considerable power, even after 1648, but only at the regional level. Indeed, under Charles X (1654–1660) and Charles XI (1660–1697), it was arguably at its height in the Baltic arena, where it successively checked the Danes and held its own against Poland, Russia, and the rising power of Prussia. The turn toward absolutism under Charles XI augmented the royal finances and thus permitted the upkeep of a large peacetime standing army. Nonetheless, these were measures to strengthen Sweden as it slowly declined from the first ranks. In Professor Roberts’s words:

甚至到1648年以后瑞典仍旧是一个相当强大的国家,但只是属于地区性的。在查理十世(1654—1660年在位)和查理十一世(1660—1697年在位)时,有人争论说它在波罗的海舞台上处于高峰,成功地挡住丹麦人,顶住了波兰、俄国和兴起的普鲁士政权。在查理十一世时转向绝对专制的做法,扩大了王室的财权,有可能维持一支和平时期的庞大常备军。不过,这些都是在瑞典逐渐从一流国家下降时用来加强自己的措施。用罗伯特教授的话说:

For a generation Sweden had been drunk with victory and bloated with booty: Charles XI led her back into the grey light of everyday existence, gave her policies appropriate to her resources and her real interests, equipped her to carry them out, and prepared for her a future of weight and dignity as a second-class power. 79

在一代人的时间里,瑞典沉湎在胜利之中,被战利品所膨胀;查理十一世把她带回日常生活的灰色光线之下,制定适合她的资源和真正利益的政策,给她以实行这些政策的装备,为她准备了符合二等强国的身份和尊严的前途。

These were not mean achievements, but in the larger European context they had limited significance. And it is interesting to note the extent to which the balance of power in the Baltic, upon which Sweden no less than Denmark, Poland, and Brandenburg depended, was being influenced and “manipulated” in the second half of the seventeenth century by the French, the Dutch, and even the English, for their own purposes, by subsidies, diplomatic interventions, and, in 1644 and 1659, a Dutch fleet. 80 Finally, while Sweden could never be called a “puppet” state in this great diplomatic game, it remained an economic midget compared with the rising powers of the West, and tended to become dependent upon their subsidies. Its foreign trade around 1700 was but a small fraction of that possessed by the United Provinces or England; its state expenditure was perhaps only one-fiftieth that of France. 81 On this inadequate material base, and without the possibility of access to overseas colonies, Sweden had little chance—despite its admirable social and administrative stability—of maintaining the military predominance that it had briefly held under Gustavus Adolphus. In the coming decades, in fact, it would have its work cut out merely seeking to arrest the advances of Prussia in the south and Russia in the east.

这些成就并不小,只是在更大的欧洲范围内它们的意义有限。值得注意的是,波罗的海的权力平衡的程度,即瑞典和丹麦、波兰以及勃兰登堡所依赖的权力平衡的程度,在17世纪后半叶是受法国、荷兰,甚至英国(为了它们自己的利益)影响和“操纵”的,手段是财政补助和外交干涉,在1644年和1659年则是一支荷兰舰队。最后,当瑞典在这场外交大战中不再能被称为“傀儡”国家的时候,比起西方兴起的强国,它仍然是一个经济侏儒,总要依靠它们的补贴。在1700年前后,它的外贸不过是联合省或英国的很小的一部分;它的政府开支大概只有法国的1/50。在这个不坚实的物质基础上,又没有可能获得海外殖民地,瑞典尽管有令人羡慕的社会和政治稳定性,却再没有机会保持在古斯塔夫·阿道弗斯统治下所取得的短期军事优势。事实上,在以后的几十年里,它始终要抓紧防备,想办法阻止普鲁士从南方、俄罗斯从东部的进攻。

The final example, that of Dutch power in this period, offers a remarkable contrast to the Swedish case. Here was a nation created in the confused circumstances of revolution, a cluster of seven heterogenous provinces separated by irregular borders from the rest of the Habsburg-owned Netherlands, a mere part of a part of a vast dynastic empire, restricted in population and territorial extent, which swiftly became a great power inside and outside Europe for almost a century. It differed from the other states—although not from its Italian forerunner, Venice—in possessing a republican, oligarchic form of government; but its most distinctive characteristic was that the foundations of its strength were firmly anchored in the world of trade, industry, and finance. It was, to be sure, a formidable military power, at least in defense; and it was the most effective naval power until eclipsed by England in the later seventeenth century. But those manifestations of armed might were the consequences, rather than the essence, of Dutch strength and influence.

最后一个例子是这个时期的荷兰政权,它与瑞典形成鲜明的对比。它是在革命的混乱局面中产生的国家,是由7个各不相同的省份组成的集团,这些省份以不规则的边界与哈布斯堡所属尼德兰的其余部分分割开来,只是一个大王朝帝国中的一小部分,人口和领土都很有限,但迅速变成了欧洲内外的一大强国,并持续几乎一个世纪。它与其他国家的不同之处是,有一个共和式的、寡头政治形式的政府,虽然这点和意大利的前身威尼斯是相同的。但它真正的特点是,它的力量的基础牢固地建立在贸易、工业和金融领域。它当然是一个了不起的军事强国,至少在防御方面是如此。直到17世纪后期英国的海军兴起,它一直是最有力量的海上强国。但这些武装力量的表现只是荷兰的力量和影响的结果,而不是本质。

It was hardly the case, of course, that in the early years of their revolt the 70,000 or so Dutch rebels counted for much in European affairs; indeed, it was not for some decades that they regarded themselves as a separate nation at all, and not until the early seventeenth century that the boundaries were in any way formed. The socalled Revolt of the Netherlands was in the beginning a sporadic affair, during which different social groups and regions fought against each other as well as opposing—and sometimes compromising with—their Habsburg rulers; and there were various moments in the 1580s when the Duke of Parma’s superbly conducted policy of recovering the territories for Spain looked on the verge of success. But for the subsidies and military aid from England and other Protestant states, the importation of large numbers of English guns, and the frequent diversion of the Spanish armies into France, the rebellion then might have been brought to an end. Yet since the ports and shipyards of the Netherlands were nearly all in rebel hands, and Spain found it impossible to gain control of the sea, Parma could reconquer only by slow, landward siege operations which lost their momentum whenever he was ordered to march his armies into France. 82

当然,在他们暴动的早期,这7万余荷兰暴动者在欧洲事务中没起什么作用,实际上几十年后他们才把自己看成一个单独的国家,到17世纪初期边界才形成。所谓尼德兰的起义一开始只是零星分散的事件,这其中不同的社会集团和地区互相争斗,同时也反对他们的哈布斯堡统治者,有时也与哈布斯堡妥协,在16世纪80年代就有好几次。当帕尔玛公爵为西班牙收复领土进行卓越的指挥时,他几乎看到了胜利。要不是来自英国和其他新教国家的补贴和援助,要不是进口了大量的英国枪炮,要不是西班牙军队被频繁地调往法国,暴动在那时可能就被镇压下去了。由于港口和船坞几乎全都在起义者手里,西班牙不可能掌握制海权,帕尔玛只能用慢速的、陆上包围的作战法,一旦他得到命令把军队开往法国,这种作战就失去了力量。

By the 1590s, then, the United Provinces had survived and could, in fact, reconquer most of the provinces and towns which had been lost in the east. Its army was by that stage well trained and led by Maurice of Nassau, whose tactical innovations and exploitation of the watery terrain made him one of the great captains of the age. To call it a Dutch army would be a misnomer: in 1600 it consisted of forty-three English, thirty-two French, twenty Scots, eleven Walloon, and nine German companies, and only seventeen Dutch companies. 83 Despite this large (but by no means untypical) variety of nationalities, Maurice molded his forces into a coherent, standardized whole. He was undoubtedly aided in this, however, by the financial underpinning provided by the Dutch government; and his army, more than most in Europe, was regularly paid, just as the government continually provided for the maintenance of its substantial navy.

于是到了16世纪90年代,联合省留存下来了,而且有可能夺回东部失去的大部分省份和城镇。到这一阶段,它的军队也已训练有素,由拿骚的莫里斯指挥,他的战术发明和利用沼泽地作战的本领使他成为当时最好的指挥官之一。称之为荷兰军队是不恰当的:在1600年它有43个英国人联队,32个法国人联队,20个苏格兰人联队,11个华龙人联队,9个德意志人联队,只有7个荷兰人联队。尽管民族大混杂(但并非不典型),莫里斯却把它铸成一个一致的、标准的整体。毫无疑问,荷兰政府的财政能支持帮助他完成这个任务,他的军队比欧洲大部分军队更能按期得到薪饷,正如政府一贯为支持强大的海军而提供经费一样。

It would be unwise to exaggerate the wealth and financial stability of the Dutch republic or to suggest that it found it easy to pay for the prolonged conflict, especially in its early stages. In the eastern and southern parts of the United Provinces, the war caused considerable damage, loss of trade, and decline in population. Even the prosperous province of Holland found the tax burdens enormous; in 1579 it had to provide 960,000 florins for the war, in 1599 almost 5. 5 million florins. By the early seventeenth century, with the annual costs of the war against Spain rising to 10 million florins, many wondered how much longer the struggle could be maintained without financial strain. Fortunately for the Dutch, Spain’s economy—and its corresponding ability to pay the mutiny-prone Army of Flanders—had suffered even more, and at last caused Madrid to agree to the truce of 1609.

夸大荷兰共和国的财富和财政稳定,或者说它能轻松地支付这场长期冲突是不明智的,特别是在它的早期阶段。在联合省的东部和南部,战争造成相当大的破坏,贸易损失,人口下降,甚至繁荣的荷兰省也感到税收太重;1579年它要为战争拿出96万佛罗林,1595年几乎达550万佛罗林。到17世纪初,反西班牙的年度费用升到1 000万佛罗林,很多人担心,这场战争不用坚持多久就会造成财政困难。荷兰的幸运在于遭受损失更大的西班牙的经济,以及与其相应的、供养爱闹事的佛兰德军的能力,终于迫使马德里同意1609年的停火。

Yet if the conflict had tested Dutch resources, it had not exhausted them; and the fact was that from the 1590s onward, its economy was growing fast, thus providing a solid foundation of “credit” when the government turned—as all belligerent states had to turn—to the money market. One obvious reason for this prosperity was the interaction of a growing population with a more entrepreneurial spirit, once the Habsburg rule had been cast off. In addition to the natural increase in numbers, there were tens (perhaps hundreds) of thousands of refugees from the south, and many others from elsewhere in Europe. It seems clear that many of these immigrants were skilled workers, teachers, craftsmen, and capitalists, with much to offer. The sack of Antwerp by Spanish troops in 1576 gave a boost to Amsterdam’s chances in the international trading system, yet it was also true that the Dutch took every opportunity offered them for commercial advancement. Their domination of the rich herring trade and their reclamation of land from the sea provided additional sources of wealth. Their vast mercantile marine, and in particular their fluyts (simple, robust freighters), earned them the carrying trade of much of Europe by 1600: timber, grain, cloth, salt, herrings were transported by Dutch vessels along every waterway. To the disgust of their English allies, and of many Dutch Calvinist divines, Amsterdam traders would willingly supply such goods to their mortal enemy, Spain, if the profits outweighed the risks. At home, raw materials were imported in vast quantities and then “finished” by the various trades of Amsterdam, Delft, Leyden, and so on. With “sugar refining, melting, distilling, brewing, tobacco cutting, silk throwing, pottery, glass, armament manufacture, printing, paper making”84 among the chief industries, it was hardly surprising that by 1622 around 56 percent of Holland’s population of 670,000 lived in medium-sized towns. Every other region in the world must have seemed economically backward by comparison.

战争考验了荷兰的资源,但并没有耗尽他们。实际情况是,从16世纪90年代开始经济发展迅速,当政府像所有的参战国那样需要向金融市场借债时,它有一个牢固的基础。经济繁荣的一个明显原因是,人口增长与摆脱哈布斯堡统治以后的更旺盛的进取精神相互作用。除了自然人口增长率外,还有来自南边或欧洲其他地区的好几万(或许几十万)难民。看起来很清楚,这些移民大都是技术工人、教师、手艺人和资本家,有很多东西可以贡献。1576年西班牙军队攻陷安特卫普,这给阿姆斯特丹更多的机会在国际贸易体系中起作用,而荷兰人确实也是利用一切可乘之机发展贸易。他们控制有利的鲱鱼贸易,开垦海田,都增加了资源。他们的大型贸易船队,特别是那种简单结实的货船,到1600年包揽了欧洲大部分运输业,木材、粮食、布匹、盐、鲱鱼,由荷兰船只通过每条水路运输。促使他们的英国盟友和荷兰卡尔文派牧师反感的是,阿姆斯特丹的商人竟然愿意把这类物资运给他们的死敌西班牙,只要利润超过风险。国内进口大批原材料,由阿姆斯特丹、德尔夫特和莱登等地的各行各业“加工”。主要的工业有“糖加工、冶金、蒸馏、酿造、制烟、缫丝、制陶、玻璃、军工、印刷、造纸”,不用惊讶,到1622年,荷兰的67万人口中有56%生活在中等城镇里。世界上任何其他地区与之相比都显得落后了。

Two further aspects of the Dutch economy enhanced its military power. The first was its overseas expansion. Although this commerce did not compare with the humbler but vaster bulk trade in European waters, it was another addition to the republic’s resources. “Between 1598 and 1605, on average twenty-five ships sailed to West Africa, twenty to Brazil, ten to the East Indies, and 150 to the Caribbean every year. Sovereign colonies were founded at Amboina in 1605 and Ternate in 1607; factories and trading posts were established around the Indian Ocean, near the mouth of the Amazon and (in 1609) in Japan. ”85 Like England, the United Provinces were now benefiting from that slow shift in the economic balances from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic world which was one of the main secular trends of the period 1500–1700; and which, while working at first to the advantage of Portugal and Spain, was later galvanizing societies better prepared to extract the profits of global commerce. 86

荷兰经济的另外两个方面也增强了它的军事实力。其一是海外扩张。虽然这项贸易与欧洲水域低级的但大宗的买卖不能相比,但也是共和国的另一项来源。“从1598年到1605年,每年有25只船到西非,20只船到巴西,10只船到东印度群岛,150只船到加勒比海。1605年在安汶,1607年在德那地建立有主权的殖民地;在印度洋周围,亚马孙河口和日本(1609年)一带都建立了工厂和贸易站。”联合省和英国一样,在经济活动从地中海向大西洋世界逐渐转移的过程中得到了好处,而这个转移是1500年到1700年期间的主要世俗潮流之一;它开始对葡萄牙人和西班牙人有利,后来就给那些更有能力从全球商业获利的政权以强大的刺激。

The second feature was Amsterdam’s growing role as the center of international finance, a natural corollary to the republic’s function as the shipper, exchanger, and commodity dealer of Europe. What its financiers and institutions offered (receiving deposits at interest, transferring monies, crediting and clearing bills of exchange, floating loans) was not different from practices already established in, say, Venice and Genoa; but, reflecting the United Provinces’ trading wealth, it was on a larger scale and conducted with a greater degree of certainty—the more so since the chief investors were a part of the government, and wished to see the principles of sound money, secure credit, and regular repayment of debt upheld. In consequence of all this, there was usually money available for government loans, which gave the Dutch Republic an inestimable advantage over its rivals; and since its credit rating was firm because it promptly repaid debts, it could borrow more cheaply than any other government—a major advantage in the seventeenth century and, indeed, at all times!

第二个特点是阿姆斯特丹成长为国际金融中心,这是这个共和国充当欧洲的船运商、交换人和商品经济人的必然结果。金融家和机构所能提供的(接受有息存款,转移款项,给汇票记账和结算,发行债券),与威尼斯和热那亚等地已实行的做法没有什么不同。但它反映出联合王国的贸易财富规模更大,可靠性更强,特别是因为主要投资者是政府的一部分,愿意想办法保持货币可靠、有保证的信誉和定期偿还债务的原则。这样的结果是,总是有钱借给政府,这使荷兰共和国比它的敌人具有无可估量的优势;由于它的信用好,还债及时,总可以用比任何其他政府优惠的条件借到钱。这在17世纪是个主要优势,实际上任何时候都是如此。

This ability to raise loans easily was the more important after the resumption of hostilities with Spain in 1621, for the cost of the armed forces rose steadily, from 13. 4 million florins (1622) to 18. 8 million florins (1640). These were large sums even for a rich population to bear, and the more particularly since Dutch overseas trade was being hurt by the war, either through direct losses or by the diversion of commerce into neutral hands. It was therefore politically easier to permit as large a part of the war as possible to be financed from public loans. Although this led to a massive increase in the official debt—the Province of Holland’s debt was 153 million florins in 1651—the economic strength of the country and the care with which interest was repaid meant that the credit system was never in danger of collapse. 87 While this demonstrates that even wealthy states winced at the cost of military expenditures, it also confirmed that as long as success in war depended upon the length of one’s purse, the Dutch were always likely to outstay the others.

1621年与西班牙再次开战以后,这种能够轻易举债的能力就更重要了,因为武装力量的费用不断上升,从1 340万佛罗林(1622年)增至1 880万佛罗林(1640年)。即使对一个人口众多的国家来说,这也是一笔巨款,特别是因为荷兰的海外贸易因战争而受损失,或者是直接损失,或者是贸易转入中立国手中。因此,尽可能让公共贷款支持大部分战争费用在政治上容易些。虽然这是造成公债猛增——荷兰省在1651年的债务为1.53亿佛罗林——这个国家的经济活力以及对偿付利息的谨慎态度意味着信用体系从没有过垮台的危险。虽然它显示了即使富国也在军事支出面前的退缩,它也证实了,战争胜利,取决于各方钱包的大小,而荷兰总能比其他国家耗得长久。