CHAPTER 10

第十章

SPACIOUS SKIES AND TILTED AXES

辽阔的天空与偏斜的轴线

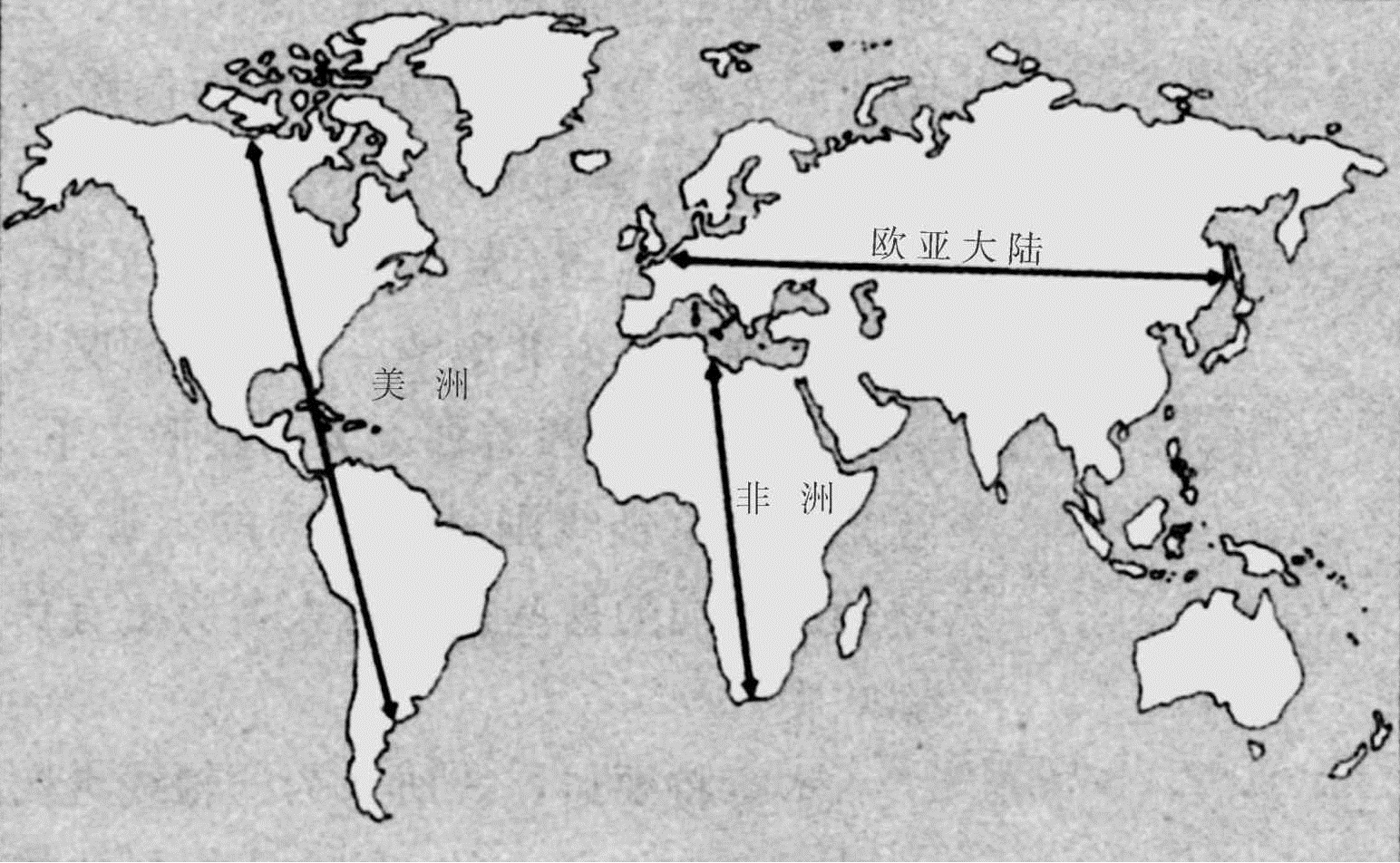

ON THE MAP OF THE WORLD ON CHAPTER 10 177 (FIGURE 10.1), compare the shapes and orientations of the continents. You'll be struck by an obvious difference. The Americas span a much greater distance north-south (9,000 miles) than east-–west: only 3,000 miles at the widest, narrowing to a mere 40 miles at the Isthmus of Panama. That is, the major axis of the Americas is north-–south. The same is also true, though to a less extreme degree, for Africa. In contrast, the major axis of Eurasia is east-–west. What effect, if any, did those differences in the orientation of the continents' axes have on human history?

请在下页的世界地图(图10.1)上比较一下各大陆的形状和轴线走向。你会对一种明显的差异产生深刻的印象。美洲南北向距离(9000英里)比东西向距离大得多:东西最宽处只有3000英里,最窄处在巴拿马地峡,仅为40英里。就是说,美洲的主轴线是南北向的。非洲的情况也是一样,只是程度没有那么大。相形之下,欧亚大陆的主轴线则是东西向的。那么,大陆轴线走向的这些差异对人类历史有什么影响呢?

Figure 10.1. Major axes of the continents

图10.1 各大陆的主轴线

This chapter will be about what I see as their enormous, sometimes tragic, consequences. Axis orientations affected the rate of spread of crops and livestock, and possibly also of writing, wheels, and other inventions. That basic feature of geography thereby contributed heavily to the very different experiences of Native Americans, Africans, and Eurasians in the last 500 years.

本章将要讨论我所认为的轴线走向的差异所产生的巨大的、有时是悲剧性的后果。轴线走向影响了作物和牲口的传播速度,可能还影响文字、车轮和其他发明的传播速度。这种基本的地理特征在过去500年中对印第安人、非洲人和欧亚大陆人十分不同的经验的形成起了巨大的促进作用。

FOOD PRODUCTION'S SPREAD proves as crucial to understanding geographic differences in the rise of guns, germs, and steel as did its origins, which we considered in the preceding chapters. That's because, as we saw in Chapter 5, there were no more than nine areas of the globe, perhaps as few as five, where food production arose independently. Yet, already in prehistoric times, food production became established in many other regions besides those few areas of origins. All those other areas became food producing as a result of the spread of crops, livestock, and knowledge of how to grow them and, in some cases, as a result of migrations of farmers and herders themselves.

粮食生产的传播对于了解在枪炮、病菌和钢铁的出现方面的地理差异,同粮食生产的起源一样证明是决定性的。关于粮食生产的起源问题,我们在前几章已经考察过了。正如我们在第五章中所看到的那样,这是因为地球上独立出现粮食生产的地区多则9个,少则5个。然而,在史前时期,除了这少数几个粮食生产的发源地外,在其他许多地区也已有了粮食生产。所有这些其他地区之所以出现粮食生产,是由于作物、牲口以及栽种作物和饲养牲口的知识的传播,在某些情况下,则是由于农民和牧人本身迁移的结果。

The main such spreads of food production were from Southwest Asia to Europe, Egypt and North Africa, Ethiopia, Central Asia, and the Indus Valley; from the Sahel and West Africa to East and South Africa; from China to tropical Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Korea, and Japan; and from Mesoamerica to North America. Moreover, food production even in its areas of origin became enriched by the addition of crops, livestock, and techniques from other areas of origin.

粮食生产的这种传播的主要路线,是从西南亚到欧洲、埃及和北非、埃塞俄比亚、中亚和印度河河谷;从萨赫勒地带和西非到东非和南非;从中国到热带东南亚、菲律宾、印度尼西亚、朝鲜和日本;以及从中美洲到北美洲。此外,粮食生产甚至在它的发源地由于来自其他发源地的另外一些作物、牲口和技术而变得更加丰富了。

Just as some regions proved much more suitable than others for the origins of food production, the ease of its spread also varied greatly around the world. Some areas that are ecologically very suitable for food production never acquired it in prehistoric times at all, even though areas of prehistoric food production existed nearby. The most conspicuous such examples are the failure of both farming and herding to reach Native American California from the U.S. Southwest or to reach Australia from New Guinea and Indonesia, and the failure of farming to spread from South Africa's Natal Province to South Africa's Cape. Even among all those areas where food production did spread in the prehistoric era, the rates and dates of spread varied considerably. At the one extreme was its rapid spread along east-west axes: from Southwest Asia both west to Europe and Egypt and east to the Indus Valley (at an average rate of about 0.7 miles per year); and from the Philippines east to Polynesia (at 3.2 miles per year). At the opposite extreme was its slow spread along north-south axes: at less than 0.5 miles per year, from Mexico northward to the U.S. Southwest; at less than 0.3 miles per year, for corn and beans from Mexico northward to become productive in the eastern United States around A.D. 900; and at 0.2 miles per year, for the llama from Peru north to Ecuador. These differences could be even greater if corn was not domesticated in Mexico as late as 3500 B.C., as I assumed conservatively for these calculations, and as some archaeologists now assume, but if it was instead domesticated considerably earlier, as most archaeologists used to assume (and many still do).

正如某些地区证明比其他地区更适合于出现粮食生产一样,粮食生产传播的难易程度在全世界也是大不相同的。有些从生态上看十分适合于粮食生产的地区,在史前期根本没有学会粮食生产,虽然史前粮食生产的一些地区就在它们的附近。这方面最明显的例子,是农业和畜牧业没有能从美国西南部传入印第安人居住的加利福尼亚,也没有能从新几内亚和印度尼西亚传入澳大利亚;农业没有能从南非的纳塔尔省传入南非的好望角省。即使在所有那些在史前期传播了粮食生产的地区中,传播的速度和年代也有很大的差异。在一端是粮食生产沿东西轴线迅速传播:从西南亚向西传入欧洲和埃及,向东传入印度河河谷(平均速度为每年约0.7英里);从菲律宾向东传入波利尼西亚(每年3.2英里)。在另一端是粮食生产沿南北轴线缓慢传播:以每年不到0.5英里的速度从墨西哥向北传入美国的西南部;玉米和豆类以每年不到0.3英里的速度从墨西哥向北传播,在公元900年左右成为美国东部的多产作物;美洲驼以每年不到0.2英里的速度从秘鲁向北传入厄瓜多尔。如果不是像我过去的保守估计和某些考古学家现在所假定的那样,迟至公元前3500年玉米才得到驯化,而是像大多数考古学家过去经常假定(其中许多人现在仍这样假定)的那样,玉米驯化的年代要大大提前,那么上述差异甚至可能更大。

There were also great differences in the completeness with which suites of crops and livestock spread, again implying stronger or weaker barriers to their spreading. For instance, while most of Southwest Asia's founder crops and livestock did spread west to Europe and east to the Indus Valley, neither of the Andes' domestic mammals (the llama / alpaca and the guinea pig) ever reached Mesoamerica in pre-Columbian times. That astonishing failure cries out for explanation. After all, Mesoamerica did develop dense farming populations and complex societies, so there can be no doubt that Andean domestic animals (if they had been available) would have been valuable for food, transport, and wool. Except for dogs, Mesoamerica was utterly without indigenous mammals to fill those needs. Some South American crops nevertheless did succeed in reaching Mesoamerica, such as manioc, sweet potatoes, and peanuts. What selective barrier let those crops through but screened out llamas and guinea pigs?

在全套作物和牲口是否得到完整的传播这方面也存在着巨大的差异,从而又一次意味着传播所碰到的障碍有强弱之分。例如,虽然西南亚的大多数始祖作物和牲口的确向西传入了欧洲,向东传入了印度河河谷,但在安第斯山脉驯养的哺乳动物(美洲驼/羊驼和豚鼠)在哥伦布以前没有一种到达过中美洲。这种未能得到传播的令人惊异的现象迫切需要予以解释。毕竟,中美洲已有了稠密的农业人口和复杂的社会,因此毫无疑问,安第斯山脉的家畜(如果有的话)大概是提供肉食、运输和毛绒的重要来源。然而,除狗外,中美洲完全没有土生土长的哺乳动物来满足这些需要。不过,有些南美洲作物还是成功地到达了中美洲,如木薯、甘薯和花生。是什么选择性的阻碍让这些作物通过,却筛选掉美洲驼和豚鼠?

A subtler expression of this geographically varying ease of spread is the phenomenon termed preemptive domestication. Most of the wild plant species from which our crops were derived vary genetically from area to area, because alternative mutations had become established among the wild ancestral populations of different areas. Similarly, the changes required to transform wild plants into crops can in principle be brought about by alternative new mutations or alternative courses of selection to yield equivalent results. In this light, one can examine a crop widespread in prehistoric times and ask whether all of its varieties show the same wild mutation or same transforming mutation. The purpose of this examination is to try to figure out whether the crop was developed in just one area or else independently in several areas.

对于物种传播的这种地理上的难易差别,有一个比较巧妙的说法,叫做抢先驯化现象。大多数后来成为我们的作物的野生植物在遗传方面因地而异,因为在不同地区的野生祖先种群中已经确立了不同的遗传突变体。同样,把野生植物变成作物所需要的变化,原则上可以通过不同的新的突变或产生相同结果的不同的选择过程来予以实现。根据这一点,人们可以考察一下在史前期广泛传播的某种作物,并且问一问它的所有变种是否显示了同样的野生突变或同样的转化突变。这种考察的目的,是要断定这种作物是在一个地区发展起来的,还是在几个地区独立发展起来的。

If one carries out such a genetic analysis for major ancient New World crops, many of them prove to include two or more of those alternative wild variants, or two or more of those alternative transforming mutations. This suggests that the crop was domesticated independently in at least two different areas, and that some varieties of the crop inherited the particular mutation of one area while other varieties of the same crop inherited the mutation of another area. On this basis, botanists conclude that lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus), common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and chili peppers of the Capsicum annuum / chinense group were all domesticated on at least two separate occasions, once in Mesoamerica and once in South America; and that the squash Cucurbita pepo and the seed plant goosefoot were also domesticated independently at least twice, once in Mesoamerica and once in the eastern United States. In contrast, most ancient Southwest Asian crops exhibit just one of the alternative wild variants or alternative transforming mutations, suggesting that all modern varieties of that particular crop stem from only a single domestication.

如果对新大陆的古代主要作物进行这种遗传分析,其中有许多证明是包括两个或更多的不同的野生变种,或两个或更多的不同的转化突变体。这表明,这个作物是在至少两个不同的地区独立驯化的,这个作物的某些变种经遗传而获得了一个地区特有的突变,而同一作物的另一些变种则通过遗传而获得了另一地区的突变。根据这个基本原理,一些植物学家断定说,利马豆、菜豆和辣椒全都在至少两个不同的场合得到驯化,一次是在中美洲,一次是在南美洲;而南瓜属植物和种子植物藜也至少独立驯化过两次,一次是在中美洲,一次是在美国东部。相形之下,西南亚的大多数古代作物显示出只有一个不同的野生变种或不同的转化突变体,从而表明了该作物的所有现代变种都起源于仅仅一次的驯化。

What does it imply if the same crop has been repeatedly and independently domesticated in several different parts of its wild range, and not just once and in a single area? We have already seen that plant domestication involves the modification of wild plants so that they become more useful to humans by virtue of larger seeds, a less bitter taste, or other qualities. Hence if a productive crop is already available, incipient farmers will surely proceed to grow it rather than start all over again by gathering its not yet so useful wild relative and redomesticating it. Evidence for just a single domestication thus suggests that, once a wild plant had been domesticated, the crop spread quickly to other areas throughout the wild plant's range, preempting the need for other independent domestications of the same plant. However, when we find evidence that the same wild ancestor was domesticated independently in different areas, we infer that the crop spread too slowly to preempt its domestication elsewhere. The evidence for predominantly single domestications in Southwest Asia, but frequent multiple domestications in the Americas, might thus provide more subtle evidence that crops spread more easily out of Southwest Asia than in the Americas.

如果这种作物是在其野生产地的几个不同地区反复地、独立地驯化的,而不是仅仅一次和在一个地区驯化的,那么这又意味着什么呢?我们已经看到,植物驯化就是把野生植物加以改变,使它们凭借较大的种子、较少的苦味或其他品质而变得对人类有益。因此,如果已经有了某种多产的作物,早期的农民肯定会去种植它,而不会从头开始去采集它的还不是那样有用的野生亲缘植物来予以重新驯化。支持仅仅一次驯化的证据表明,一旦某种野生植物得到了驯化,那么这种作物就在这种野生植物的整个产地迅速向其他地区传播,抢先满足了其他地区对同一种植物独立驯化的需要。然而,如果我们发现有证据表明,同一种植物的野生祖先在不同地区独立地得到驯化,我们就可以推断出这种作物传播得太慢,无法抢先阻止其他地方对这种植物的驯化。关于在西南亚主要是一次性驯化而在美洲则是频繁的多次驯化的证据,也许因此而提供了关于作物的传播在西南亚比在美洲容易的更巧妙的证据。

Rapid spread of a crop may preempt domestication not only of the same wild ancestral species somewhere else but also of related wild species. If you're already growing good peas, it's of course pointless to start from scratch to domesticate the same wild ancestral pea again, but it's also pointless to domesticate closely related wild pea species that for farmers are virtually equivalent to the already domesticated pea species. All of Southwest Asia's founder crops preempted domestication of any of their close relatives throughout the whole expanse of western Eurasia. In contrast, the New World presents many cases of equivalent and closely related, but nevertheless distinct, species having been domesticated in Mesoamerica and South America. For instance, 95 percent of the cotton grown in the world today belongs to the cotton species Gossypium hirsutum, which was domesticated in prehistoric times in Mesoamerica. However, prehistoric South American farmers instead grew the related cotton Gossypium barbadense. Evidently, Mesoamerican cotton had such difficulty reaching South America that it failed in the prehistoric era to preempt the domestication of a different cotton species there (and vice versa). Chili peppers, squashes, amaranths, and chenopods are other crops of which different but related species were domesticated in Mesoamerica and South America, since no species was able to spread fast enough to preempt the others.

某种作物的迅速传播可能不但抢先阻止了同一植物的野生祖先在其他某个地方的驯化,而且也阻止了有亲缘关系的野生植物的驯化。如果你所种的豌豆已经是优良品种,那么从头开始再去驯化同一种豌豆的野生祖先,当然是毫无意义的,但是去驯化近亲的野豌豆品种也同样是毫无意义的,因为对农民来说,这种豌豆和已经驯化的豌豆实际上是同一回事。西南亚所有的始祖作物抢先阻止了对欧亚大陆西部整个广大地区任何近亲植物的驯化。相比之下,在新大陆有许多例子表明,一些同等重要的、有密切亲缘关系的然而又有区别的植物,是在中美洲和南美洲驯化的。例如,今天全世界种植的棉花有95%属于史前时期在中美洲驯化的短绒棉。然而,史前期南美洲农民种植的却是巴巴多斯棉。显然,中美洲的棉花难以到达南美洲,才使它未能在史前时代抢先阻止那里不同品种的棉花得到驯化(反之亦然)。辣椒、南瓜属植物、苋属植物和藜科植物是另一些作物,它们的一些不同的然而有亲缘关系的品种是在中美洲和南美洲驯化的,因为没有一个品种的传播速度能够快到抢先阻止其他品种的驯化。

We thus have many different phenomena converging on the same conclusion: that food production spread more readily out of Southwest Asia than in the Americas, and possibly also than in sub-Saharan Africa. Those phenomena include food production's complete failure to reach some ecologically suitable areas; the differences in its rate and selectivity of spread; and the differences in whether the earliest domesticated crops preempted redomestications of the same species or domestications of close relatives. What was it about the Americas and Africa that made the spread of food production more difficult there than in Eurasia?

因此,许多不同的现象归结为同一个结论:粮食生产从西南亚向外传播的速度要比在美洲快,而且也可能比在非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南的地区快。这些现象包括:粮食生产完全未能到达某些生态条件适合于粮食生产的地区;粮食生产传播的速度和选择性方面存在着差异;以及最早驯化的作物是否抢先阻止了对同一种植物的再次驯化或对近亲植物的驯化方面也存在着差异。粮食生产的传播在美洲和非洲比在欧亚大陆困难,这又是怎么一回事呢?

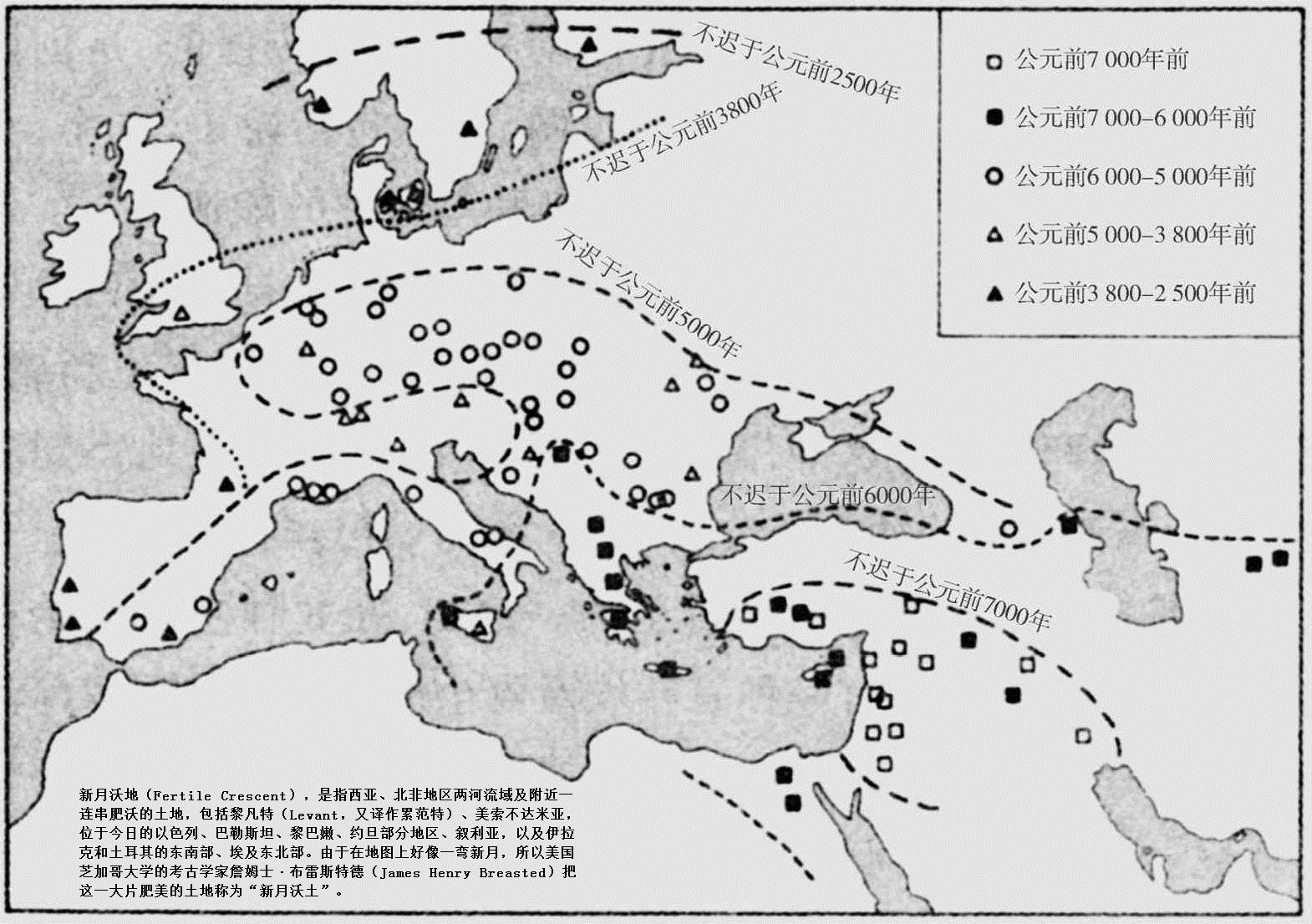

TO ANSWER THIS question, let's begin by examining the rapid spread of food production out of Southwest Asia (the Fertile Crescent). Soon after food production arose there, somewhat before 8000 B.C., a centrifugal wave of it appeared in other parts of western Eurasia and North Africa farther and farther removed from the Fertile Crescent, to the west and east. On this page I have redrawn the striking map (Figure 10.2) assembled by the geneticist Daniel Zohary and botanist Maria Hopf, in which they illustrate how the wave had reached Greece and Cyprus and the Indian subcontinent by 6500 B.C., Egypt soon after 6000 B.C., central Europe by 5400 B.C., southern Spain by 5200 B.C., and Britain around 3500 B.C. In each of those areas, food production was initiated by some of the same suite of domestic plants and animals that launched it in the Fertile Crescent. In addition, the Fertile Crescent package penetrated Africa southward to Ethiopia at some still-uncertain date. However, Ethiopia also developed many indigenous crops, and we do not yet know whether it was these crops or the arriving Fertile Crescent crops that launched Ethiopian food production.

要回答这个问题,让我们先来看一看粮食生产从西南亚(新月沃地)向外迅速传播的情况。在那里出现粮食生产后不久,即稍早于公元前8000年,粮食生产从中心向外扩散的浪潮在欧亚大陆西部和北非的其他地方出现了,它往东西两个方向传播,离新月沃地越来越远。在本页上我画出了遗传学家丹尼尔·左哈利和植物学家玛丽娅·霍普夫汇编的明细图(图10.2),他们用图来说明粮食生产的浪潮到公元前6500年到达希腊、塞浦路斯和印度次大陆,在公元前6000年后不久到达埃及,到公元前5400年到达中欧,到公元前5200年到达西班牙南部,到公元前3500年左右到达英国。在上述的每一个地区,粮食生产都是由最早在新月沃地驯化的同一组动植物中的某些作物和牲口所引发的。另外,新月沃地的整套作物和牲口在某个仍然无法确定的年代进入非洲,向南到了埃塞俄比亚。然而,埃塞俄比亚也发展了许多本地的作物,目前我们还不知道是否就是这些作物或陆续从新月沃地引进的作物开创了埃塞俄比亚的粮食生产。

新月沃地作物向欧亚大陆西部的传播

Figure 10.2. The symbols show early radiocarbon-dated sites where remains of Fertile Crescent crops have been found. □ = the Fertile Crescent itself (sites before 7000 B.C.). Note that dates become progressively later as one gets farther from the Fertile Crescent. This map is based on Map 20 of Zohary and Hopf's Domestication of Plants in the Old World but substitutes calibrated radiocarbon dates for their uncalibrated dates.

图10.2 图中符号表明发现新月沃地作物残骸的用碳-14测定法测定的早期地点。□ = 新月沃地本身(公元前7000年前的地点)。注意:离新月沃地渐远,则年代亦渐晚。本图据左哈利和霍普夫的《旧大陆植物驯化图20》绘制,但以经过校正的碳-14测定法测定的年代代替其未经校正的年代。

Of course, not all pieces of the package spread to all those outlying areas: for example, Egypt was too warm for einkorn wheat to become established. In some outlying areas, elements of the package arrived at different times: for instance, sheep preceded cereals in southwestern Europe. Some outlying areas went on to domesticate a few local crops of their own, such as poppies in western Europe and watermelons possibly in Egypt. But most food production in outlying areas depended initially on Fertile Crescent domesticates. Their spread was soon followed by that of other innovations originating in or near the Fertile Crescent, including the wheel, writing, metalworking techniques, milking, fruit trees, and beer and wine production.

当然,这全部作物和牲口并非全都传播到那些边远地区。例如,埃及太温暖,不利于单粒小麦在那里落户。在有些边远地区,在这全部作物和牲口中,有些是在不同的时期引进的。例如,在西南欧,绵羊引进的时间早于谷物。有些边远地区也着手驯化几种本地的作物,如欧洲西部的罂粟,可能还有埃及的西瓜。但边远地区的大部分粮食生产,在开始时都依赖新月沃地驯化的动植物。紧跟在这些驯化的动植物之后传播的,是创始于新月沃地或其附近地区的其他发明,其中包括轮子、文字、金属加工技术、挤奶、果树栽培以及啤酒和葡萄酒的酿造。

Why did the same plant package launch food production throughout western Eurasia? Was it because the same set of plants occurred in the wild in many areas, were found useful there just as in the Fertile Crescent, and were independently domesticated? No, that's not the reason. First, many of the Fertile Crescent's founder crops don't even occur in the wild outside Southwest Asia. For instance, none of the eight main founder crops except barley grows wild in Egypt. Egypt's Nile Valley provides an environment similar to the Fertile Crescent's Tigris and Euphrates Valleys. Hence the package that worked well in the latter valleys also worked well enough in the Nile Valley to trigger the spectacular rise of indigenous Egyptian civilization. But the foods to fuel that spectacular rise were originally absent in Egypt. The sphinx and pyramids were built by people fed on crops originally native to the Fertile Crescent, not to Egypt.

为什么这一批植物竟能使粮食生产在欧亚大陆整个西部得以开始?这是不是因为在许多地区都有一批这样的野生植物,它们在那里和在新月沃地一样被发现有用,从而独立地得到驯化?不,不是这个原因。首先,新月沃地的始祖作物有许多原来甚至不是在西南亚以外地区野生的。例如,在8种主要的始祖作物中,除大麦外,没有一种是在埃及野生的。埃及的尼罗河流域提供了一种类似于新月沃地的底格里斯河和幼发拉底河流域的环境。因此,在两河流域生长良好的那一批作物,在尼罗河流域也生长得相当良好,从而引发了埃及本土文明的引人注目的兴起。但是,促使埃及文明的这种令人注目的兴起的粮食,在埃及原来是没有的。建造人面狮身像和金字塔的人吃的是新月沃地原生的作物,而不是埃及原生的作物。

Second, even for those crops whose wild ancestor does occur outside of Southwest Asia, we can be confident that the crops of Europe and India were mostly obtained from Southwest Asia and were not local domesticates. For example, wild flax occurs west to Britain and Algeria and east to the Caspian Sea, while wild barley occurs east even to Tibet. However, for most of the Fertile Crescent's founding crops, all cultivated varieties in the world today share only one arrangement of chromosomes out of the multiple arrangements found in the wild ancestor; or else they share only a single mutation (out of many possible mutations) by which the cultivated varieties differ from the wild ancestor in characteristics desirable to humans. For instance, all cultivated peas share the same recessive gene that prevents ripe pods of cultivated peas from spontaneously popping open and spilling their peas, as wild pea pods do.

其次,即使在西南亚以外地区确曾出现过这些作物的野生祖先,我们也能够肯定欧洲和印度的作物大都得自西南亚,而不是在当地驯化的。例如,野生亚麻往西出现在英国和阿尔及利亚,往东出现在里海沿岸,而野生大麦往东甚至出现在西藏。然而,就新月沃地的大多数始祖作物而言,今天世界上所有人工培育的品种的染色体都只有一种排列,而它们野生祖先的染色体却有多种排列;要不,就是它们只产生一种突变(来自许多可能的突变),而由于有了这种突变,人工培育的品种和它们的野生祖先的区别就在于它们有了为人类所向往的一些特点。例如,所有人工培育的豌豆都有相同的隐性基因,这种基因使人工培育的豌豆的成熟豆荚不会像野豌豆的豆荚那样自然爆裂,把豌豆洒落地上。

Evidently, most of the Fertile Crescent's founder crops were never domesticated again elsewhere after their initial domestication in the Fertile Crescent. Had they been repeatedly domesticated independently, they would exhibit legacies of those multiple origins in the form of varied chromosomal arrangements or varied mutations. Hence these are typical examples of the phenomenon of preemptive domestication that we discussed above. The quick spread of the Fertile Crescent package preempted any possible other attempts, within the Fertile Crescent or elsewhere, to domesticate the same wild ancestors. Once the crop had become available, there was no further need to gather it from the wild and thereby set it on the path to domestication again.

显然,新月沃地的大多数始祖作物在它们最初在新月沃地驯化后,就不会在其他地方再次驯化。如果它们是多次独立驯化的,它们的染色体的不同排列或不同的突变就会显示出这种多重起源所遗留的影响。因此,这些就是我们在前面讨论的关于抢先驯化现象的典型例子。新月沃地成批作物的迅速传播,抢先阻止了其他任何可能想要在新月沃地范围内或其他地方驯化同一野生祖先的企图。一旦有了这种作物,就再没有必要把它从野外采集来,使它再一次走上驯化之路。

The ancestors of most of the founder crops have wild relatives, in the Fertile Crescent and elsewhere, that would also have been suitable for domestication. For example, peas belong to the genus Pisum, which consists of two wild species:?Pisum sativum, the one that became domesticated to yield our garden peas, and Pisum fulvum, which was never domesticated. Yet wild peas of Pisum fulvum taste good, either fresh or dried, and are common in the wild. Similarly, wheats, barley, lentil, chickpea, beans, and flax all have numerous wild relatives besides the ones that became domesticated. Some of those related beans and barleys were indeed domesticated independently in the Americas or China, far from the early site of domestication in the Fertile Crescent. But in western Eurasia only one of several potentially useful wild species was domesticated—probably because that one spread so quickly that people soon stopped gathering the other wild relatives and ate only the crop. Again as we discussed above, the crop's rapid spread preempted any possible further attempts to domesticate its relatives, as well as to redomesticate its ancestor.

在新月沃地和其他地方,大多数始祖作物的祖先都有可能也适于驯化的野生亲缘植物。例如,豌豆是豌豆属植物,这个属包括两个野生品种:豌豆和黄豌豆,前者经过驯化而成为我们园圃里的豌豆,后者则从未得到驯化。然而,野生的黄豌豆无论是新鲜的还是干的,味道都很好,而且在野外随处可见。同样,小麦、大麦、兵豆、鹰嘴豆、菜豆和亚麻,除已经驯化的品种外,全都有许多野生的亲缘植物。在这些有亲缘关系的豆类和大麦类作物中,有一些事实上是在美洲或中国独立驯化的,离新月沃地的早期驯化地点已经很远。但在欧亚大陆西部,在几个具有潜在价值的野生品种中,只有一种得到了驯化——这大概是因为这一个品种传播得太快,所以人们停止采集其他的野生亲缘植物,而只以这种作物为食。又一次像我们前面讨论过的那样,这种作物的迅速传播不但抢先阻止了驯化其野生祖先的企图,而且也阻止了任何可能想要进一步驯化其亲缘植物的企图。

WHY WAS THE spread of crops from the Fertile Crescent so rapid? The answer depends partly on that east-west axis of Eurasia with which I opened this chapter. Localities distributed east and west of each other at the same latitude share exactly the same day length and its seasonal variations. To a lesser degree, they also tend to share similar diseases, regimes of temperature and rainfall, and habitats or biomes (types of vegetation). For example, Portugal, northern Iran, and Japan, all located at about the same latitude but lying successively 4,000 miles east or west of each other, are more similar to each other in climate than each is to a location lying even a mere 1,000 miles due south. On all the continents the habitat type known as tropical rain forest is confined to within about 10 degrees latitude of the equator, while Mediterranean scrub habitats (such as California's chaparral and Europe's maquis) lie between about 30 and 40 degrees of latitude.

为什么作物从新月沃地向外传播的速度如此之快?回答部分地决定于我在本章开始时谈到的欧亚大陆的东西向轴线。位于同一纬度的东西两地,白天的长度和季节的变化完全相同。在较小程度上,它们也往往具有类似的疾病、温度和雨量情势以及动植物生境或生物群落区(植被类型)。例如,葡萄牙、伊朗北部和日本在纬度上的位置大致相同,彼此东西相隔各为4000英里,但它们在气候方面都很相似,而各自的气候与其正南方仅仅1000英里处的气候相比反而存在差异。在各个大陆上,被称为热带雨林型的动植物生境都在赤道以南和赤道以北大约10度之内,而地中海型低矮丛林的动植物生境(如加利福尼亚的沙巴拉群落[1]和欧洲的灌木丛林地带)则是在北纬大约30度至40度之间。

But the germination, growth, and disease resistance of plants are adapted to precisely those features of climate. Seasonal changes of day length, temperature, and rainfall constitute signals that stimulate seeds to germinate, seedlings to grow, and mature plants to develop flowers, seeds, and fruit. Each plant population becomes genetically programmed, through natural selection, to respond appropriately to signals of the seasonal regime under which it has evolved. Those regimes vary greatly with latitude. For example, day length is constant throughout the year at the equator, but at temperate latitudes it increases as the months advance from the winter solstice to the summer solstice, and it then declines again through the next half of the year. The growing season—that is, the months with temperatures and day lengths suitable for plant growth—is shortest at high latitudes and longest toward the equator. Plants are also adapted to the diseases prevalent at their latitude.

但是,植物的发芽、生长和抗病能力完全适应了这些气候特点。白天长度、温度和雨量的季节性变化,成了促使种子发芽、幼苗生长以及成熟的植物开花、结子和结果的信号。每一个植物种群都通过自然选择在遗传上作好安排,对它在其中演化的季节性情势所发出的信号作出恰当的反应。这种季节性的情势因纬度的不同而产生巨大的变化。例如,在赤道白天的长度全年固定不变,但在温带地区,随着时间从冬至向夏至推进,白天逐步变长,然后在整个下半年又逐步变短。生长季节——即温度与白天长度适合植物生长的那一段时间——在高纬度地区最短,在靠近赤道地区最长。植物对它们所处地区的流行疾病也能适应。

Woe betide the plant whose genetic program is mismatched to the latitude of the field in which it is planted! Imagine a Canadian farmer foolish enough to plant a race of corn adapted to growing farther south, in Mexico. The unfortunate corn plant, following its Mexico-adapted genetic program, would prepare to thrust up its shoots in March, only to find itself still buried under 10 feet of snow. Should the plant become genetically reprogrammed so as to germinate at a time more appropriate to Canada—say, late June—the plant would still be in trouble for other reasons. Its genes would be telling it to grow at a leisurely rate, sufficient only to bring it to maturity in five months. That's a perfectly safe strategy in Mexico's mild climate, but in Canada a disastrous one that would guarantee the plant's being killed by autumn frosts before it had produced any mature corn cobs. The plant would also lack genes for resistance to diseases of northern climates, while uselessly carrying genes for resistance to diseases of southern climates. All those features make low-latitude plants poorly adapted to high-latitude conditions, and vice versa. As a consequence, most Fertile Crescent crops grow well in France and Japan but poorly at the equator.

那些在遗传安排方面未能配合栽种地区纬度的植物可要遭殃了!请想象一下,一个加拿大农民如果愚蠢到竟会栽种一种适于在遥远的南方墨西哥生长的玉米,那会有什么样的结果。这种玉米按照它那适合在墨西哥生长的遗传安排,应该在三月份就准备好发芽,但结果却发现自己仍被埋在10英尺厚的积雪之下。如果这种玉米在遗传上重新安排,以便使它在一个更适合于加拿大的时间里——如六月份的晚些时候发芽,那么它仍会由于其他原因而碰到麻烦。它的基因会吩咐它从容不迫地生长,只要能在5个月之后成熟就行了。这在墨西哥的温和气候下是一种十分安全的做法,但在加拿大就是一种灾难性的做法了,因为这保证会使玉米在能够长出任何成熟的玉米棒之前就被秋霜杀死了。这种玉米也会缺少抵抗北方气候区的疾病的基因,而空自携带着抵抗南方气候区的疾病的基因。所有这些特点使低纬度地区的植物难以适应高纬度地区的条件,反之亦然。结果,新月沃地的大多数作物在法国和日本生长良好,但在赤道则生长很差。

Animals too are adapted to latitude-related features of climate. In that respect we are typical animals, as we know by introspection. Some of us can't stand cold northern winters with their short days and characteristic germs, while others of us can't stand hot tropical climates with their own characteristic diseases. In recent centuries overseas colonists from cool northern Europe have preferred to emigrate to the similarly cool climates of North America, Australia, and South Africa, and to settle in the cool highlands within equatorial Kenya and New Guinea. Northern Europeans who were sent out to hot tropical lowland areas used to die in droves of diseases such as malaria, to which tropical peoples had evolved some genetic resistance.

动物也一样,能够适应与纬度有关的气候特点。在这方面,我们就是典型的动物,这是我们通过内省知道的。我们中有些人受不了北方的寒冬,受不了那里短暂的白天和特有的病菌,而我们中的另一些人则受不了炎热的热带气候和那里特有的病菌。在近来的几个世纪中,欧洲北部凉爽地区的海外移民更喜欢迁往北美、澳大利亚和南非的同样凉爽的气候区,而在赤道国家肯尼亚和新几内亚,则喜欢住在凉爽的高原地区。被派往炎热的热带低地地区的北欧人过去常常成批地死于疟疾之类的疾病,而热带居民对这类疾病已经逐步形成了某种自然的抵抗力。

That's part of the reason why Fertile Crescent domesticates spread west and east so rapidly: they were already well adapted to the climates of the regions to which they were spreading. For instance, once farming crossed from the plains of Hungary into central Europe around 5400 B.C., it spread so quickly that the sites of the first farmers in the vast area from Poland west to Holland (marked by their characteristic pottery with linear decorations) were nearly contemporaneous. By the time of Christ, cereals of Fertile Crescent origin were growing over the 8,000-mile expanse from the Atlantic coast of Ireland to the Pacific coast of Japan. That west-east expanse of Eurasia is the largest land distance on Earth.

这就是新月沃地驯化的动植物如此迅速地向东西两个方向传播的部分原因:它们已经很好地适应了它们所传播的地区的气候。例如,农业在公元前5400年左右越过匈牙利平原进入中欧后立即迅速传播,所以从波兰向西直到荷兰的广大地区内最早的农民遗址(其标志为绘有线条装饰图案的特有陶器)几乎是同时存在的。到公元元年,原产新月沃地的谷物已在从爱尔兰的大西洋沿岸到日本的太平洋沿岸的8000英里的大片地区内广为种植。欧亚大陆的这片东西向的广阔地区是地球上最大的陆地距离。

Thus, Eurasia's west-east axis allowed Fertile Crescent crops quickly to launch agriculture over the band of temperate latitudes from Ireland to the Indus Valley, and to enrich the agriculture that arose independently in eastern Asia. Conversely, Eurasian crops that were first domesticated far from the Fertile Crescent but at the same latitudes were able to diffuse back to the Fertile Crescent. Today, when seeds are transported over the whole globe by ship and plane, we take it for granted that our meals are a geographic mishmash. A typical American fast-food restaurant meal would include chicken (first domesticated in China) and potatoes (from the Andes) or corn (from Mexico), seasoned with black pepper (from India) and washed down with a cup of coffee (of Ethiopian origin). Already, though, by 2,000 years ago, Romans were also nourishing themselves with their own hodgepodge of foods that mostly originated elsewhere. Of Roman crops, only oats and poppies were native to Italy. Roman staples were the Fertile Crescent founder package, supplemented by quince (originating in the Caucasus); millet and cumin (domesticated in Central Asia); cucumber, sesame, and citrus fruit (from India); and chicken, rice, apricots, peaches, and foxtail millet (originally from China). Even though Rome's apples were at least native to western Eurasia, they were grown by means of grafting techniques that had developed in China and spread westward from there.

因此,欧亚大陆的东西向轴线使新月沃地的作物迅速开创了从爱尔兰到印度河流域的温带地区的农业,并丰富了亚洲东部独立出现的农业。反过来,最早在远离新月沃地但处于同一纬度的地区驯化的作物也能够传回新月沃地。今天,当种子靠船只和飞机在全世界运来运去的时候,我们理所当然地认为我们的一日三餐是个地理大杂烩。美国快餐店的一顿典型的饭食可能包括鸡(最早在中国驯化)和土豆(来自安第斯山脉)或玉米(来自墨西哥),用黑胡椒粉(来自印度)调味,再喝上一杯咖啡(原产埃塞俄比亚)以帮助消化。然而,不迟于2000年前,罗马人也已用多半在别处出产的食物大杂烩来养活自己。在罗马人的作物中,只有燕麦和罂粟是意大利当地生产的。罗马人的主食是新月沃地的一批始祖作物,再加上榅桲(原产高加索山脉)、小米和莳萝(在中亚驯化)、黄瓜、芝麻和柑橘(来自印度),以及鸡、米、杏、桃和粟(原产中国)。虽然罗马的苹果至少是欧亚大陆西部的土产,但对苹果的种植却要借助于在中国发展起来并从那里向西传播的嫁接技术。

While Eurasia provides the world's widest band of land at the same latitude, and hence the most dramatic example of rapid spread of domesticates, there are other examples as well. Rivaling in speed the spread of the Fertile Crescent package was the eastward spread of a subtropical package that was initially assembled in South China and that received additions on reaching tropical Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and New Guinea. Within 1,600 years that resulting package of crops (including bananas, taro, and yams) and domestic animals (chickens, pigs, and dogs) had spread more than 5,000 miles eastward into the tropical Pacific to reach the islands of Polynesia. A further likely example is the east-west spread of crops within Africa's wide Sahel zone, but paleobotanists have yet to work out the details.

虽然欧亚大陆有着世界上处于同一纬度的最广阔的陆地,并由此提供了关于驯化的动植物迅速传播的最引人注目的例子,但还有其他一些例子。在传播速度上堪与新月沃地整批作物相比的是一批亚热带作物的向东传播,这些作物最初集中在华南,在到达热带东南亚、菲律宾、印度尼西亚和新几内亚时又增加了一些新的作物。在1600年内,由此而产生的那一批作物(包括香蕉、芋艿和薯蓣)向东传播了5000多英里,进入热带太平洋地区,最后到达波利尼西亚群岛。还有一个似乎可信的例子,是作物在非洲广阔的萨赫勒地带内从东向西的传播,但古植物学家仍然需要弄清楚这方面的详细情况。

CONTRAST THE EASE of east-west diffusion in Eurasia with the difficulties of diffusion along Africa's north-south axis. Most of the Fertile Crescent founder crops reached Egypt very quickly and then spread as far south as the cool highlands of Ethiopia, beyond which they didn't spread. South Africa's Mediterranean climate would have been ideal for them, but the 2,000 miles of tropical conditions between Ethiopia and South Africa posed an insuperable barrier. Instead, African agriculture south of the Sahara was launched by the domestication of wild plants (such as sorghum and African yams) indigenous to the Sahel zone and to tropical West Africa, and adapted to the warm temperatures, summer rains, and relatively constant day lengths of those low latitudes.

可以把驯化的植物在欧亚大陆东西向传播之易与沿非洲南北轴线传播之难作一对比。新月沃地的大多数始祖作物很快就到达了埃及,然后向南传播,直到凉爽的埃塞俄比亚高原地区,它们的传播也就到此为止。南非的地中海型气候对这些作物来说应该是理想的,但在埃塞俄比亚与南非之间的那2000英里的热带环境成了一道不可逾越的障碍。撒哈拉沙漠以南地区的非洲农业是从驯化萨赫勒地带和热带西非的当地野生植物(如高粱和非洲薯蓣)开始的,这些植物已经适应了这些低纬度地区的温暖气候、夏季的持续降雨和相对固定不变的白天长度。

Similarly, the spread southward of Fertile Crescent domestic animals through Africa was stopped or slowed by climate and disease, especially by trypanosome diseases carried by tsetse flies. The horse never became established farther south than West Africa's kingdoms north of the equator. The advance of cattle, sheep, and goats halted for 2,000 years at the northern edge of the Serengeti Plains, while new types of human economies and livestock breeds were being developed. Not until the period A.D. 1–200, some 8,000 years after livestock were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, did cattle, sheep, and goats finally reach South Africa. Tropical African crops had their own difficulties spreading south in Africa, arriving in South Africa with black African farmers (the Bantu) just after those Fertile Crescent livestock did. However, those tropical African crops could never be transmitted across South Africa's Fish River, beyond which they were stopped by Mediterranean conditions to which they were not adapted.

同样,新月沃地的家畜通过非洲向南的传播也由于气候和疾病(尤其是采采蝇传染的锥虫病)而停止或速度减慢。马匹所到的地方从来没有超过赤道以北的一些西非王国。在2000年中,牛、绵羊和山羊在塞伦格蒂大平原的北缘一直止步不前,而人类的新型经济和牲畜品种却仍在发展。直到公元元年至公元200年这一时期,即牲畜在新月沃地驯化的大约8000年之后,牛、绵羊和山羊才终于到达南非。热带非洲的作物在非洲向南传播时也遇到了困难,它们只是在新月沃地的那些牲畜引进之后才随着黑非洲农民(班图族)到达南非。然而,这些热带非洲的作物没有能够传播到南非的菲什河彼岸,因为它们不能适应的地中海型气候条件阻止了它们的前进。

The result was the all-too-familiar course of the last two millennia of South African history. Some of South Africa's indigenous Khoisan peoples (otherwise known as Hottentots and Bushmen) acquired livestock but remained without agriculture. They became outnumbered and were replaced northeast of the Fish River by black African farmers, whose southward spread halted at that river. Only when European settlers arrived by sea in 1652, bringing with them their Fertile Crescent crop package, could agriculture thrive in South Africa's Mediterranean zone. The collisions of all those peoples produced the tragedies of modern South Africa: the quick decimation of the Khoisan by European germs and guns; a century of wars between Europeans and blacks; another century of racial oppression; and now, efforts by Europeans and blacks to seek a new mode of coexistence in the former Khoisan lands.

这个结果是过去2000年的南非历史中人们非常熟悉的过程。南非土著科伊桑人(亦称霍屯督人和布须曼人)有些已有了牲畜,但仍没有农业。他们在人数上不敌黑非洲农民,并在菲什河东北地区被黑非洲农民取而代之,但这些黑非洲农民的向南扩张也到菲什河为止。只有在欧洲移民于1652年由海路到达,带来新月沃地的一整批作物时,农业才得以在南非的地中海型气候带兴旺发达起来。所有这些民族之间的冲突,造成了现代南非的一些悲剧:欧洲的病菌和枪炮使科伊桑人迅速地大量死亡;欧洲人和黑人之间发生了长达一个世纪的一系列战争;发生了又一个世纪的种族压迫;现在,欧洲人和黑人正在作出努力,在昔日科伊桑人的土地上寻找一种新的共处模式。

CONTRAST ALSO THE ease of diffusion in Eurasia with its difficulties along the Americas' north-south axis. The distance between Mesoamerica and South America—say, between Mexico's highlands and Ecuador's—is only 1,200 miles, approximately the same as the distance in Eurasia separating the Balkans from Mesopotamia. The Balkans provided ideal growing conditions for most Mesopotamian crops and livestock, and received those domesticates as a package within 2,000 years of its assembly in the Fertile Crescent. That rapid spread preempted opportunities for domesticating those and related species in the Balkans. Highland Mexico and the Andes would similarly have been suitable for many of each other's crops and domestic animals. A few crops, notably Mexican corn, did indeed spread to the other region in the pre-Columbian era.

还可以把驯化的植物在欧亚大陆传播之易与沿美洲南北轴线传播之难作一对比。中美洲与南美洲之间的距离——例如墨西哥高原地区与厄瓜多尔高原地区之间的距离——只有1200英里,约当欧亚大陆上巴尔干半岛与美索不达米亚之间的距离。巴尔干半岛为大多数美索不达米亚的作物和牲畜提供了理想的生长环境,并在不到2000年的时间内接受了这一批在新月沃地形成的驯化动植物。这种迅速的传播抢先剥夺了驯化那些动植物和亲缘物种的机会。墨西哥高原地区和安第斯山脉对彼此的许多作物和牲畜来说同样应该是合适的生长环境。有几种作物,特别是墨西哥玉米,确实在哥伦布时代以前就已传播到另一个地区。

But other crops and domestic animals failed to spread between Mesoamerica and South America. The cool highlands of Mexico would have provided ideal conditions for raising llamas, guinea pigs, and potatoes, all domesticated in the cool highlands of the South American Andes. Yet the northward spread of those Andean specialties was stopped completely by the hot intervening lowlands of Central America. Five thousand years after llamas had been domesticated in the Andes, the Olmecs, Maya, Aztecs, and all other native societies of Mexico remained without pack animals and without any edible domestic mammals except for dogs.

但其他一些作物和牲畜未能在中美洲和南美洲之间传播。凉爽的墨西哥高原地区应该是饲养美洲驼、豚鼠和种植马铃薯的理想环境,因为它们全都是在南美安第斯山脉凉爽的高原地区驯化的。然而,安第斯山脉的这些特产在向北传播时被横隔在中间的中美洲炎热的低地完全阻挡住了。在美洲驼于安第斯山脉驯化了5000年之后,奥尔梅克人的、马雅人的、阿兹特克人的以及墨西哥其他所有土著人的社会仍然没有驮畜,而且除狗以外也没有任何可供食用的驯养的哺乳动物。

Conversely, domestic turkeys of Mexico and domestic sunflowers of the eastern United States might have thrived in the Andes, but their southward spread was stopped by the intervening tropical climates. The mere 700 miles of north-south distance prevented Mexican corn, squash, and beans from reaching the U.S. Southwest for several thousand years after their domestication in Mexico, and Mexican chili peppers and chenopods never did reach it in prehistoric times. For thousands of years after corn was domesticated in Mexico, it failed to spread northward into eastern North America, because of the cooler climates and shorter growing season prevailing there. At some time between A.D. 1 and A.D. 200, corn finally appeared in the eastern United States but only as a very minor crop. Not until around A.D. 900, after hardy varieties of corn adapted to northern climates had been developed, could corn-based agriculture contribute to the flowering of the most complex Native American society of North America, the Mississippian culture—a brief flowering ended by European-introduced germs arriving with and after Columbus.

反过来,墨西哥驯养的火鸡和美国东部种植的向日葵本来也是可以在安第斯山脉茁壮生长的,但它们在向南传播时被隔在中间的热带气候区阻挡住了。仅仅这700英里的南北距离就使墨西哥的玉米、南瓜类植物和豆类植物在墨西哥驯化了几千年之后仍然不能到达美国的西南部,而墨西哥的辣椒和藜科植物在史前时期也从未到达那里。在玉米于墨西哥驯化后的几千年中,它都未能向北传播到北美的东部,其原因是那里的气候普遍较冷和生长季节普遍较短。在公元元年到200年之间的某一个时期,玉米终于在美国的东部出现,但还只是一种十分次要的作物。直到公元900年左右,在培育出能适应北方气候的耐寒的玉米品种之后,以玉米为基础的农业才得以为北美最复杂的印第安人社会——密西西比文化作出贡献,不过这种繁荣只是昙花一现,由于同哥伦布一起到来的和在他之后到来的欧洲人带来的病菌而寿终正寝。

Recall that most Fertile Crescent crops prove, upon genetic study, to derive from only a single domestication process, whose resulting crop spread so quickly that it preempted any other incipient domestications of the same or related species. In contrast, many apparently widespread Native American crops prove to consist of related species or even of genetically distinct varieties of the same species, independently domesticated in Mesoamerica, South America, and the eastern United States. Closely related species replace each other geographically among the amaranths, beans, chenopods, chili peppers, cottons, squashes, and tobaccos. Different varieties of the same species replace each other among the kidney beans, lima beans, the chili pepper Capsicum annuum / chinense, and the squash Cucurbita pepo. Those legacies of multiple independent domestications may provide further testimony to the slow diffusion of crops along the Americas' north-south axis.

可以回想一下,根据遗传研究,新月沃地的大多数作物证明只是一次驯化过程的产物,这个过程所产生的作物传播很快,抢先阻止了对相同品种或亲缘品种植物的任何其他的早期驯化。相比之下,许多显然广为传播的印第安作物中,却包含有一些亲缘植物,或甚至属于同一品种但产生了遗传变异的变种,而这些作物又都是在中美洲、南美洲和美国东部独立驯化出来的。从地区来看,在苋属植物、豆类植物、藜科植物、辣椒、棉花、南瓜属植物和烟草中,近亲的品种互相接替。在四季豆、利马豆、中国辣椒和瓠瓜中,同一品种的不同变种互相接替。这种由多次独立驯化所产生的结果,也许可以提供关于作物沿美洲南北轴线缓慢传播的进一步证明。

Africa and the Americas are thus the two largest landmasses with a predominantly north-south axis and resulting slow diffusion. In certain other parts of the world, slow north-south diffusion was important on a smaller scale. These other examples include the snail's pace of crop exchange between Pakistan's Indus Valley and South India, the slow spread of South Chinese food production into Peninsular Malaysia, and the failure of tropical Indonesian and New Guinean food production to arrive in prehistoric times in the modern farmlands of southwestern and southeastern Australia, respectively. Those two corners of Australia are now the continent's breadbaskets, but they lie more than 2,000 miles south of the equator. Farming there had to await the arrival from faraway Europe, on European ships, of crops adapted to Europe's cool climate and short growing season.

于是,非洲和美洲这两个最大的陆块,由于它们的轴线主要是南北走向,故而产生了作物传播缓慢的结果。在世界上的其他一些地区,南北之间的缓慢传播只在较小范围内产生重要的影响。这方面的另一些例子包括作物在巴基斯坦的印度河流域与南印度之间十分缓慢的交流,华南的粮食生产向西马来西亚的缓慢传播,以及热带印度尼西亚和新几内亚的粮食生产未能在史前时期分别抵达澳大利亚西南部和东南部的现代农田。澳大利亚的这两个角落现在是这个大陆的粮仓,但它们却远在赤道以南2000多英里之外。那里的农业得等到适应欧洲凉爽气候和较短生长季节的作物乘坐欧洲人的船只从遥远的欧洲来到的那个时候。

I HAVE BEEN dwelling on latitude, readily assessed by a glance at a map, because it is a major determinant of climate, growing conditions, and ease of spread of food production. However, latitude is of course not the only such determinant, and it is not always true that adjacent places at the same latitude have the same climate (though they do necessarily have the same day length). Topographic and ecological barriers, much more pronounced on some continents than on others, were locally important obstacles to diffusion.

我一直在强调只要看一眼就可容易地在地图上确定的纬度,因为它是气候、生长环境和粮食生产传播难易的主要决定因素。然而,纬度当然不是这方面唯一的决定因素,认为同一纬度上的邻近地区有着同样的气候(虽然它们不一定有着同样的白天长度),这种说法也并不总是正确的。地形和生态方面的界线,在某些大陆比在另一些大陆要明显得多,从而在局部上造成了对作物传播的重大障碍。

For instance, crop diffusion between the U.S. Southeast and Southwest was very slow and selective although these two regions are at the same latitude. That's because much of the intervening area of Texas and the southern Great Plains was dry and unsuitable for agriculture. A corresponding example within Eurasia involved the eastern limit of Fertile Crescent crops, which spread rapidly westward to the Atlantic Ocean and eastward to the Indus Valley without encountering a major barrier. However, farther eastward in India the shift from predominantly winter rainfall to predominantly summer rainfall contributed to a much more delayed extension of agriculture, involving different crops and farming techniques, into the Ganges plain of northeastern India. Still farther east, temperate areas of China were isolated from western Eurasian areas with similar climates by the combination of the Central Asian desert, Tibetan plateau, and Himalayas. The initial development of food production in China was therefore independent of that at the same latitude in the Fertile Crescent, and gave rise to entirely different crops. However, even those barriers between China and western Eurasia were at least partly overcome during the second millennium B.C., when West Asian wheat, barley, and horses reached China.

例如,虽然美国的东南部和西南部处在同一个纬度上,但这两个地区之间的作物传播却是十分缓慢而有选择性的。这是因为横隔在中间的得克萨斯和南部大平原的很大一部分地区干旱而不适于农业。在欧亚大陆也有一个与此相一致的例子,那就是新月沃地的作物向东传播的范围。这些作物很快就向西传播到大西洋,向东传播到印度河流域,而没有碰到任何重大的障碍。然而,在印度如要再向东去,则由于主要是冬季降雨转变为主要是夏季降雨而大大延缓了涉及不同作物和耕作技术的农业向印度东北部恒河平原的扩展。如果还要向东,则有中亚沙漠、西藏高原和喜马拉雅山一起把中国的温带地区同气候相似的欧亚大陆西部地区分隔开来。因此,中国粮食生产的早期发展独立于处在同一纬度的新月沃地的粮食生产,并产生了一些完全不同的作物。然而,当公元前2000年西亚的小麦、大麦和马匹到达中国时,就连中国与欧亚大陆西部地区之间的这些障碍也至少部分地得到了克服。

By the same token, the potency of a 2,000-mile north-south shift as a barrier also varies with local conditions. Fertile Crescent food production spread southward over that distance to Ethiopia, and Bantu food production spread quickly from Africa's Great Lakes region south to Natal, because in both cases the intervening areas had similar rainfall regimes and were suitable for agriculture. In contrast, crop diffusion from Indonesia south to southwestern Australia was completely impossible, and diffusion over the much shorter distance from Mexico to the U.S. Southwest and Southeast was slow, because the intervening areas were deserts hostile to agriculture. The lack of a high-elevation plateau in Mesoamerica south of Guatemala, and Mesoamerica's extreme narrowness south of Mexico and especially in Panama, were at least as important as the latitudinal gradient in throttling crop and livestock exchanges between the highlands of Mexico and the Andes.

而且,这种南北转移2000英里所产生的阻力,也因当地条件的不同而迥异。新月沃地的粮食生产通过这样长的距离传播到埃塞俄比亚,而班图人的粮食生产从非洲的大湖区向南迅速传播到纳塔尔省,因为在这两个例子中,隔在中间的地区有相似的降雨情势,因而适合于农业。相比之下,作物要想从印度尼西亚向南传播到澳大利亚的西南部地区则是完全不可能的,而通过短得多的距离从墨西哥向美国西南部和东南部传播也因中间隔着不利于农业的沙漠地区而速度缓慢。中美洲在危地马拉以南没有高原,中美洲在墨西哥以南尤其是巴拿马地形极狭,这在阻碍墨西哥高原地区和安第斯山脉地区之间作物和牲口的交流方面,至少同纬度的梯度一样重要。

Continental differences in axis orientation affected the diffusion not only of food production but also of other technologies and inventions. For example, around 3,000 B.C. the invention of the wheel in or near Southwest Asia spread rapidly west and east across much of Eurasia within a few centuries, whereas the wheels invented independently in prehistoric Mexico never spread south to the Andes. Similarly, the principle of alphabetic writing, developed in the western part of the Fertile Crescent by 1500 B.C., spread west to Carthage and east to the Indian subcontinent within about a thousand years, but the Mesoamerican writing systems that flourished in prehistoric times for at least 2,000 years never reached the Andes.

大陆轴线走向的差异不仅影响粮食生产的传播,而且也影响其他技术和发明的传播。例如,公元前3000年左右在西南亚或其附近发明的轮子,不到几百年就从东到西迅速传到了欧亚大陆的很大一部分地区,而在史前时代墨西哥独立发明的轮子却未能传到南面的安第斯山脉地区。同样,不迟于公元前1500年在新月沃地西部发展起来的字母文字的原理,在大约1000年之内向西传到了迦太基,向东传到了印度次大陆,但在史前时期即已盛行的中美洲书写系统,经过了至少2000年时间还没有到达安第斯山脉。

Naturally, wheels and writing aren't directly linked to latitude and day length in the way crops are. Instead, the links are indirect, especially via food production systems and their consequences. The earliest wheels were parts of ox-drawn carts used to transport agricultural produce. Early writing was restricted to elites supported by food-producing peasants, and it served purposes of economically and socially complex food-producing societies (such as royal propaganda, goods inventories, and bureaucratic record keeping). In general, societies that engaged in intense exchanges of crops, livestock, and technologies related to food production were more likely to become involved in other exchanges as well.

当然,轮子和文字不像作物那样同纬度和白天长度有直接关系。相反,这种关系是间接的,主要是通过粮食生产系统及其影响来实现的。最早的轮子是用来运输农产品的牛拉大车的一部分。早期的文字只限于由生产粮食的农民养活的上层人士使用,是为在经济上和体制上都很复杂的粮食生产社会的目的服务的(如对王室的宣传、存货清单的开列和官方记录的保存)。一般说来,对作物、牲畜以及与粮食生产有关的技术进行频繁交流的社会,更有可能也从事其他方面的交流。

America's patriotic song “America the Beautiful” invokes our spacious skies, our amber waves of grain, from sea to shining sea. Actually, that song reverses geographic realities. As in Africa, in the Americas the spread of native crops and domestic animals was slowed by constricted skies and environmental barriers. No waves of native grain ever stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast of North America, from Canada to Patagonia, or from Egypt to South Africa, while amber waves of wheat and barley came to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific across the spacious skies of Eurasia. That faster spread of Eurasian agriculture, compared with that of Native American and sub-Saharan African agriculture, played a role (as the next part of this book will show) in the more rapid diffusion of Eurasian writing, metallurgy, technology, and empires.

美国的爱国歌曲《美丽的亚美利加》说到了从大海到闪光的大海,我们的辽阔的天空,我们的琥珀色的谷浪。其实,这首歌把地理的实际情况弄反了。和在非洲一样,美洲本地的作物和牲畜的传播速度由于狭窄的天空和环境的障碍而变得缓慢了。从北美大西洋岸到太平洋岸,从加拿大到巴塔哥尼亚高原,或者从埃及到南非,看不见本地绵延不断的谷浪,而琥珀色的麦浪倒是在欧亚大陆辽阔的天空下从大西洋一直延伸到太平洋。同美洲本地和撒哈拉沙漠以南非洲的农业传播速度相比,欧亚大陆农业的更快的传播速度在对欧亚大陆的文字、冶金、技术和帝国的更快传播方面发挥了作用。

To bring up all those differences isn't to claim that widely distributed crops are admirable, or that they testify to the superior ingenuity of early Eurasian farmers. They reflect, instead, the orientation of Eurasia's axis compared with that of the Americas or Africa. Around those axes turned the fortunes of history.

提出所有这些差异,并不就是说分布很广的作物是值得赞美的,也不是说这些差异证明了欧亚大陆早期农民具有过人的智慧。这些差异只是反映了欧亚大陆轴线走向与美洲或非洲大陆轴线相比较的结果。历史的命运就是围绕这些轴线旋转的。

注释:

1. 沙巴拉群落:美国加利福尼亚州南部由一种能耐干旱和寒冷的灌木植物构成的生态群。——译者