CHAPTER 12

第十二章

BLUEPRINTS AND BORROWED LETTERS

蓝图和借用字母

NINETEENTH-CENTURY AUTHORS TENDED TO INTERPRET history as a progression from savagery to civilization. Key hallmarks of this transition included the development of agriculture, metallurgy, complex technology, centralized government, and writing. Of these, writing was traditionally the one most restricted geographically: until the expansions of Islam and of colonial Europeans, it was absent from Australia, Pacific islands, subequatorial Africa, and the whole New World except for a small part of Mesoamerica. As a result of that confined distribution, peoples who pride themselves on being civilized have always viewed writing as the sharpest distinction raising them above “barbarians” or “savages.”

19世纪的作家往往把历史看作是从野蛮走向文明的进程。这一转变的主要标志,包括农业的发展、冶金、复杂的技术、集中统一的政府和文字。其中文字在传统上是最受地理限制的一种标志:在伊斯兰教和欧洲殖民者向外扩张之前,澳大利亚、太平洋诸岛、非洲赤道以南地区和除中美洲一小部分地区外的整个新大陆,都没有文字。由于囿于一隅,以文明自诩的民族总是把文字看作是使他们比“野蛮人”优越的最鲜明的特点。

Knowledge brings power. Hence writing brings power to modern societies, by making it possible to transmit knowledge with far greater accuracy and in far greater quantity and detail, from more distant lands and more remote times. Of course, some peoples (notably the Incas) managed to administer empires without writing, and “civilized” peoples don't always defeat “barbarians,” as Roman armies facing the Huns learned. But the European conquests of the Americas, Siberia, and Australia illustrate the typical recent outcome.

知识带来力量。因此,文字也给现代社会带来了力量,用文字来传播知识可以做到更准确、更大量和更详尽,在地域上可以做到传播得更远,在时间上可以做到传播得更久。当然,有些民族(引人注目的是印加人)竟能在没有文字的情况下掌管帝国,而且“文明的”民族也并不总是能打败“野蛮人”,面对匈奴人的罗马军队知道这一点。但欧洲人对美洲、西伯利亚和澳大利亚的征服,却为近代的典型结果提供了例证。

Writing marched together with weapons, microbes, and centralized political organization as a modern agent of conquest. The commands of the monarchs and merchants who organized colonizing fleets were conveyed in writing. The fleets set their courses by maps and written sailing directions prepared by previous expeditions. Written accounts of earlier expeditions motivated later ones, by describing the wealth and fertile lands awaiting the conquerors. The accounts taught subsequent explorers what conditions to expect, and helped them prepare themselves. The resulting empires were administered with the aid of writing. While all those types of information were also transmitted by other means in preliterate societies, writing made the transmission easier, more detailed, more accurate, and more persuasive.

文字同武器、病菌和集中统一的行政组织并驾齐驱,成为一种现代征服手段。组织开拓殖民地的舰队的君主和商人的命令是用文字传达的。舰队确定航线要靠以前历次探险所准备的海图和书面的航海说明。以前探险的书面记录描写了等待着征服者的财富和沃土,从而激起了对以后探险的兴趣。这些记录告诉后来的探险者可能会碰到什么情况,并帮助他们作出准备。由此产生的帝国借助文字来进行管理。虽然所有这些信息在文字出现以前的社会里也可以用其他手段来传播,但文字使传播变得更容易、更详尽、更准确、更能取信于人。

Why, then, did only some peoples and not others develop writing, given its overwhelming value? For example, why did no traditional hunters-gatherers evolve or adopt writing? Among island empires, why did writing arise in Minoan Crete but not in Polynesian Tonga? How many separate times did writing evolve in human history, under what circumstances, and for what uses? Of those peoples who did develop it, why did some do so much earlier than others? For instance, today almost all Japanese and Scandinavians are literate but most Iraqis are not: why did writing nevertheless arise nearly four thousand years earlier in Iraq?

既然文字具有这种压倒一切的价值,那么,为什么只有某些民族产生了文字,而其他民族则没有产生文字?例如,传统的狩猎采集族群为什么没有发明出自己的文字,也没有借用别人的文字?在岛屿帝国中,为什么文字出现在说弥诺斯语[1]的克里特,而不是出现在说波利尼西亚语的汤加?文字在人类历史上分别产生过几次?是在什么情况下产生的?因何种需要而产生的?在那些发明文字的民族中,为什么有些民族在这方面比另一些民族早得多?例如,今天几乎所有的日本人和斯堪的纳维亚人都识字,而大多数伊拉克人不识字:可是为什么文字的出现在伊拉克却又早了几乎4000年?

The diffusion of writing from its sites of origin also raises important questions. Why, for instance, did it spread to Ethiopia and Arabia from the Fertile Crescent, but not to the Andes from Mexico? Did writing systems spread by being copied, or did existing systems merely inspire neighboring peoples to invent their own systems? Given a writing system that works well for one language, how do you devise a system for a different language? Similar questions arise whenever one tries to understand the origins and spread of many other aspects of human culture—such as technology, religion, and food production. The historian interested in such questions about writing has the advantage that they can often be answered in unique detail by means of the written record itself. We shall therefore trace writing's development not only because of its inherent importance, but also for the general insights into cultural history that it provides.

文字从其发源地向外传播,同样提出了一些重要的问题。例如,为什么文字从新月沃地向埃塞俄比亚和阿拉伯半岛传播,但却没有从墨西哥向安第斯山脉传播?书写系统是否是通过手抄来传播的?现有的书写系统是否仅仅是启发了邻近的民族去发明他们自己的书写系统?既然一种书写系统只适合一种语言,你又如何去为另一种语言设计这样的一种书写系统呢?如果人们想要了解人类文化的其他许多方面——如技术、宗教和粮食生产的起源和传播,同样的问题也会产生。但对关于文字的这类问题感兴趣的历史学家却拥有一个有利的条件,即这些问题通常可以借助文字记载本身而得到无比详尽的回答。因此,我们可以对文字的发展作一番考查,这不仅是因为文字固有的重要性,而且也因为可以借此对文字所提供的文化史进行普遍而深入的了解。

THE THREE BASIC strategies underlying writing systems differ in the size of the speech unit denoted by one written sign: either a single basic sound, a whole syllable, or a whole word. Of these, the one employed today by most peoples is the alphabet, which ideally would provide a unique sign (termed a letter) for each basic sound of the language (a phoneme). Actually, most alphabets consist of only about 20 or 30 letters, and most languages have more phonemes than their alphabets have letters. For example, English transcribes about 40 phonemes with a mere 26 letters. Hence most alphabetically written languages, including English, are forced to assign several different phonemes to the same letter and to represent some phonemes by combinations of letters, such as the English two-letter combinations sh and th (each represented by a single letter in the Russian and Greek alphabets, respectively).

有3个基本策略构成了书写系统的基础。在由一个书写符号代表的言语单位的大小方面,这些策略是不同的:或者是一个基本的音,一个完整的音节,或者一个完整的词。在这些书写系统中,今天大多数民族使用的系统是字母表,而字母表最好要能为语言的每一个基本的音(音素)提供一个独一无二的符号(称为字母)。但实际上,大多数字母表只有20或30个左右的字母,而大多数语言的音素又多于它们的字母表中的字母。因此,大多数用字母书写的语言,包括英语,不得不给同一个字母规定几个不同的音素,并把字母组合来代表某些音素,如英语中的两个字母的组合sh和th(而在俄语和希腊语字母表中,则分别由一个字母代表一个音素)。

The second strategy uses so-called logograms, meaning that one written sign stands for a whole word. That's the function of many signs of Chinese writing and of the predominant Japanese writing system (termed kanji). Before the spread of alphabetic writing, systems making much use of logograms were more common and included Egyptian hieroglyphs, Maya glyphs, and Sumerian cuneiform.

第二个策略就是利用所谓语标,就是说用一个书写符号来代表一个完整的词。这是中国文字的许多符号的功能,也是流行的日语书写系统(称为日文汉字)的功能。在字母文字传播以前,大量利用语标的书写系统更为普通,其中包括埃及象形文字、马雅象形文字和苏美尔楔形文字。

The third strategy, least familiar to most readers of this book, uses a sign for each syllable. In practice, most such writing systems (termed syllabaries) provide distinct signs just for syllables of one consonant followed by one vowel (like the syllables of the word “fa-mi-ly”), and resort to various tricks in order to write other types of syllables by means of those signs. Syllabaries were common in ancient times, as exemplified by the Linear B writing of Mycenaean Greece. Some syllabaries persist today, the most important being the kana syllabary that the Japanese use for telegrams, bank statements, and texts for blind readers.

第三个策略是本书大多数读者最不熟悉的,也就是用一个符号代表一个音节。其实大多数这样的书写系统(称为音节文字)就是用不同的符号代表一个辅音和后面的一个元音所构成的音节(如“fa-mi-ly”这个词的音节),并采用各种不同的办法以便借助这些符号来书写其他类型的音节。音节文字在古代是很普通的,如迈锡尼时代[2]希腊的B类线形文字。有些音节文字直到今天仍有人使用,其中最重要的就是日本人用于电报、银行结单和盲人读本的假名。

I've intentionally termed these three approaches strategies rather than writing systems. No actual writing system employs one strategy exclusively. Chinese writing is not purely logographic, nor is English writing purely alphabetic. Like all alphabetic writing systems, English uses many logograms, such as numerals, $, %, and + : that is, arbitrary signs, not made up of phonetic elements, representing whole words. “Syllabic” Linear B had many logograms, and “logographic” Egyptian hieroglyphs included many syllabic signs as well as a virtual alphabet of individual letters for each consonant.

我故意把这3个方法称为策略,而不是称为书写系统。现行的书写系统没有一个是只有一种策略的。汉语的文字不是完全由语标组成的,英语的文字也不是全用字母的。同所有字母书写系统一样,英语用了许多语标,如数字、$、%和+:就是说,用了许多任意符号,这些符号代表整个的词,但不是由语音要素构成的。“由音节组成的”B类线形文字有许多语标,而“由语标组成的”埃及象形文字不但有一个含有代表每一个辅音的各别字母的实际上的字母表,而且也包括了许多音节符号。

INVENTING A WRITING system from scratch must have been incomparably more difficult than borrowing and adapting one. The first scribes had to settle on basic principles that we now take for granted. For example, they had to figure out how to decompose a continuous utterance into speech units, regardless of whether those units were taken as words, syllables, or phonemes. They had to learn to recognize the same sound or speech unit through all our normal variations in speech volume, pitch, speed, emphasis, phrase grouping, and individual idiosyncrasies of pronunciation. They had to decide that a writing system should ignore all of that variation. They then had to devise ways to represent sounds by symbols.

从头开始去发明一种书写系统,其困难程度与借用和改造一个书写系统无法相比。最早的抄写员必须拟定一些在我们今天看来是理所当然的基本原则。例如,他们必须想出办法把一连串的声音分解为一些言语单位,而不管这些单位被看作是词、音节或音素。他们必须通过我们说话时的音量、音高、语速、强调、词语组合和个人发音习惯等所有正常变化中去学会辨认相同的音或言语单位。他们必须决定,书写系统应该不去理会所有这些变化。然后,他们还必须设计出用符号来代表语音的方法。

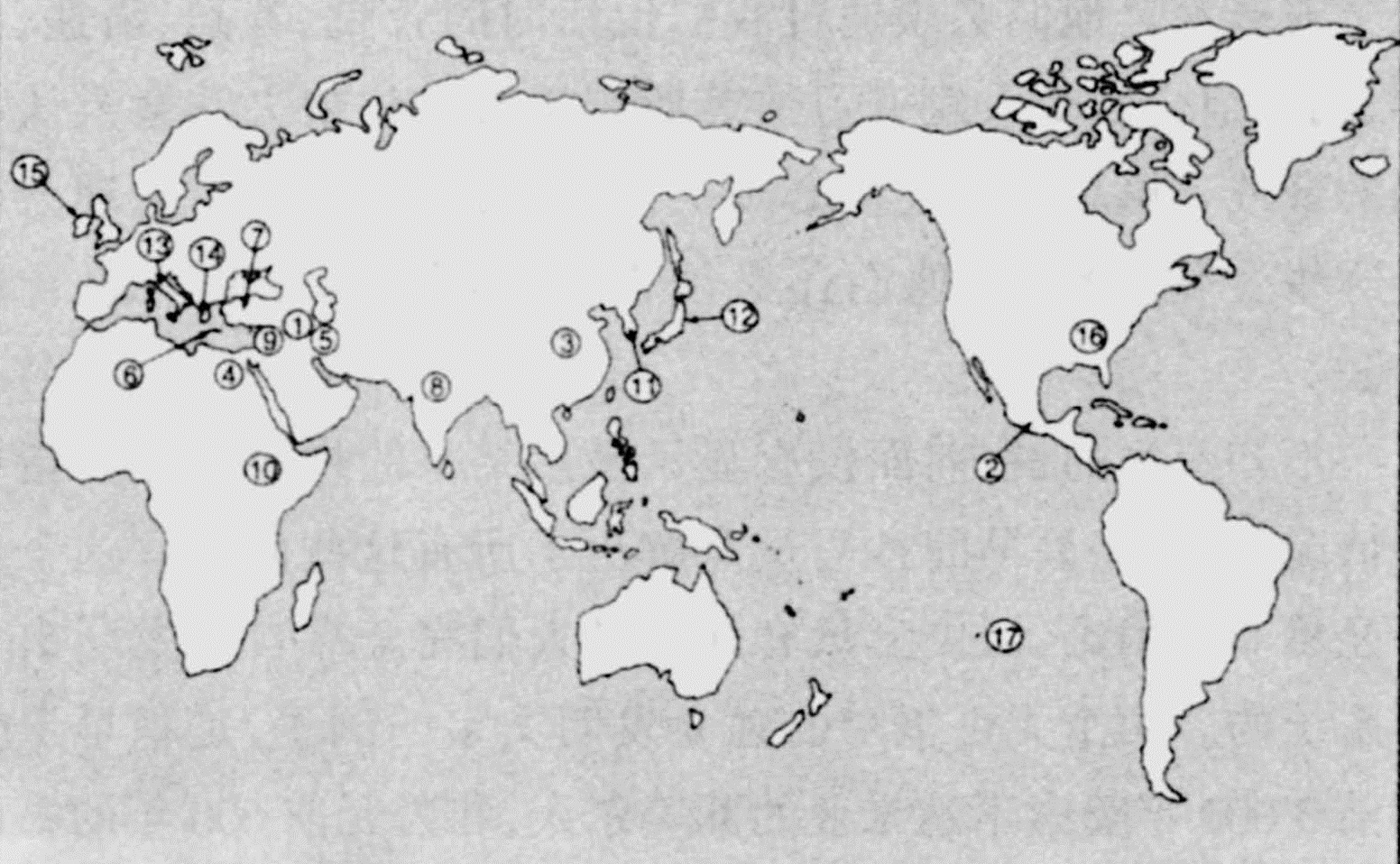

Somehow, the first scribes solved all those problems, without having in front of them any example of the final result to guide their efforts. That task was evidently so difficult that there have been only a few occasions in history when people invented writing entirely on their own. The two indisputably independent inventions of writing were achieved by the Sumerians of Mesopotamia somewhat before 3000 B.C. and by Mexican Indians before 600 B.C. (Figure 12.1); Egyptian writing of 3000 B.C. and Chinese writing (by 1300 B.C.) may also have arisen independently. Probably all other peoples who have developed writing since then have borrowed, adapted, or at least been inspired by existing systems.

不知怎么的,在前面没有显示最后结果的样板来作为指导的情况下,这些最早的抄写员竟解决了所有这些问题。这个任务显然非常困难,历史上只有几次是人们完全靠自己发明出书写系统的。两个无可争辩的独立发明文字的例子,是稍早于公元前3000年美索不达米亚的苏美尔人,和公元前600年的墨西哥印第安人(图12.1);公元前3000年的埃及文字和不迟于公元前1300年的中国文字,可能也是独立出现的。从那以后,所有其他民族可能是通过借用和改造其他文字,或至少受到现有书写系统的启发而发明了自己的文字。

The independent invention that we can trace in greatest detail is history's oldest writing system, Sumerian cuneiform (Figure 12.1). For thousands of years before it jelled, people in some farming villages of the Fertile Crescent had been using clay tokens of various simple shapes for accounting purposes, such as recording numbers of sheep and amounts of grain. In the last centuries before 3000 B.C., developments in accounting technology, format, and signs rapidly led to the first system of writing. One such technological innovation was the use of flat clay tablets as a convenient writing surface. Initially, the clay was scratched with pointed tools, which gradually yielded to reed styluses for neatly pressing a mark into the tablet. Developments in format included the gradual adoption of conventions whose necessity is now universally accepted: that writing should be organized into ruled rows or columns (horizontal rows for the Sumerians, as for modern Europeans); that the lines should be read in a constant direction (left to right for Sumerians, as for modern Europeans); and that the lines should be read from top to bottom of the tablet rather than vice versa.

我们研究得最详尽的独立发明的文字是历史上最古老的书写系统——苏美尔楔形文字(图12.1)。在这种文字定形前的几千年中,新月沃地的一些农业村舍里的人用黏土做成的各种简单形状的记号来计数,如记下羊的头数和谷物的数量。在公元3000年前的最后几百年中,记账技术、格式和符号的发展迅速导致了第一个书写系统。这方面的一个技术革新是把平平的黏土刻写板作为一种方便的书写表面。开始时是用尖器在黏土上刻划,后来这种尖器逐步让位于用芦苇秆做的尖笔,因为这种笔能在黏土板上画出整齐美观的记号。书写格式的发展包括逐步采用了今天普遍认为必不可少的一些惯例:应该把文字整整齐齐地安排在用直线画出来的行列中(苏美尔人的文字同现代欧洲人的文字一样都是横排的);一行行文字读起来应该始终顺着一个方向(苏美尔人同现代欧洲人一样都是从左到右的);以及在黏土板上逐行阅读应该是由上而下,而不是相反。

| independent or possibly independent origins |

alphabetics | others | Syllabaries |

| 独立的或可能 独立的发源地 |

字母文字 | 其他 | 音节文字 |

| 1 Sumer? | 9 West Semitic, Phoenician? | 5 Proto-Elamite | 6 Crete (Linear A and B)? |

| 苏美尔 | 米特语、腓尼基语 | 原始埃兰 | 克里特(A类和B类线形文字) |

| 2 Mesoamerica? | 10 Ethiopian? | 7 Hittite | 12 Japan (kana)? |

| 中美洲 | 埃塞俄比亚语 | 赫梯 | 日本(假名) |

| 3 ? China? | 11 Korea (han'g&l)? | 8 Indus Valley | 16 Cherokee |

| 中国 | 朝鲜(谚文) | 印度河河谷 | 切罗基 |

| 4 ?? Egypt? | 13 Italy (Roman, Etruscan)? | 17 Easter Island | |

| 埃及 | 意大利 (罗马语、伊特鲁亚语) |

复活节岛 | |

| 14 Greece | |||

| 希腊 | |||

| 15 Ireland (ogham)? | |||

| 爱尔兰(欧甘文字) |

Figure 12.1. The question marks next to China and Egypt denote some doubt whether early writing in those areas arose completely independently or was stimulated by writing systems that arose elsewhere earlier. "Other" refers to scripts that were neither alphabets nor syllabaries and that probably arose under the influence of earlier scripts

图12.1 中国和埃及旁边的问号表示这些地区的早期文字究竟是完全独立出现的,还是受到其他地区更早出现的文字的刺激而发明的,还有些疑问。“其他”所指的文字既非字母文字,亦非音节文字,它们可能是在更早的文字的影响下出现的。

But the crucial change involved the solution of the problem basic to virtually all writing systems: how to devise agreed-on visible marks that represent actual spoken sounds, rather than only ideas or else words independent of their pronunciation. Early stages in the development of the solution have been detected especially in thousands of clay tablets excavated from the ruins of the former Sumerian city of Uruk, on the Euphrates River about 200 miles southeast of modern Baghdad. The first Sumerian writing signs were recognizable pictures of the object referred to (for instance, a picture of a fish or a bird). Naturally, those pictorial signs consisted mainly of numerals plus nouns for visible objects; the resulting texts were merely accounting reports in a telegraphic shorthand devoid of grammatical elements. Gradually, the forms of the signs became more abstract, especially when the pointed writing tools were replaced by reed styluses. New signs were created by combining old signs to produce new meanings: for example, the sign for head was combined with the sign for bread in order to produce a sign signifying eat.

但是,至关重要的改变是去解决对几乎所有书写系统来说都带根本性的问题:如何去设计出人人同意的代表实际语言的显而易见的符号,而不仅仅是不顾发音的一些概念或单词。这一解决办法的早期发展阶段,在苏美尔人以前的城市乌鲁克的废墟上出土的几千块黏土板上得到了非同寻常的证明。乌鲁克位于幼发拉底河上,在现今巴格达东南大约200英里处。最早的苏美人的文字符号是一些可以认出来的所指称对象的图形(如鱼和鸟的图形)。当然,这些图形符号主要是由数字加上代表看得见的对象的名词组成的;由此而产生的文本不过是没有语法成分的简短的速记式的流水账。慢慢地,这些符号形式变得比较抽象起来,尤其是在尖头的书写工具被芦苇秆做的尖笔代替之后。把旧的符号结合起来创造出新的符号,产生了新的意义:例如,为了产生一个表示吃的意思的符号,就把代表头的符号和代表面包的符合结合在一起。

The earliest Sumerian writing consisted of nonphonetic logograms. That's to say, it was not based on the specific sounds of the Sumerian language, and it could have been pronounced with entirely different sounds to yield the same meaning in any other language—just as the numeral sign 4 is variously pronounced four, chetwíre, nelj , and empat by speakers of English, Russian, Finnish, and Indonesian, respectively. Perhaps the most important single step in the whole history of writing was the Sumerians' introduction of phonetic representation, initially by writing an abstract noun (which could not be readily drawn as a picture) by means of the sign for a depictable noun that had the same phonetic pronunciation. For instance, it's easy to draw a recognizable picture of arrow, hard to draw a recognizable picture of life, but both are pronounced ti in Sumerian, so a picture of an arrow came to mean either arrow or life. The resulting ambiguity was resolved by the addition of a silent sign called a determinative, to indicate the category of nouns to which the intended object belonged. Linguists term this decisive innovation, which also underlies puns today, the rebus principle.

最早的苏美尔文字是由不表音的语标构成的。就是说,它不是以苏美尔语言的特有发音为基础的,它可以用完全不同的发音来表示任何其他语言中的同一个意思——正如对4这个数字符号,说英语的、说俄语的、说芬兰语的和说印度尼西亚语的都有不同的发音,分别念成four、chetwire(четыре)、nelj和empat。也许整个文字史上最重要的一步是苏美尔人采用了语音符号,开始时是借助代表发音相同而又可以画出来的名词的符号来书写抽象名词。例如,要对弓画出一个可以识别的图形是容易的,但要对生命画出一个可以识别的图形就困难了,但这两者的发音在苏美尔语里都是ti,因此一张弓的图形的意思或者是弓,或者是生命。解决由此而产生的歧义是加上一个叫做义符的无声符号,以表示拟议中的对象所属的名词类别。语言学家把这种决定性的创新称之为画谜原则,也是今天构成双关语的基础。

Once Sumerians had hit upon this phonetic principle, they began to use it for much more than just writing abstract nouns. They employed it to write syllables or letters constituting grammatical endings. For instance, in English it's not obvious how to draw a picture of the common syllable-tion, but we could instead draw a picture illustrating the verb shun, which has the same pronunciation. Phonetically interpreted signs were also used to “spell out” longer words, as a series of pictures each depicting the sound of one syllable. That's as if an English speaker were to write the word believe as a picture of a bee followed by a picture of a leaf. Phonetic signs also permitted scribes to use the same pictorial sign for a set of related words (such as tooth, speech, and speaker), but to resolve the ambiguity with an additional phonetically interpreted sign (such as selecting the sign for two, each, or peak).

苏美尔人一旦偶然发现了这个语音原则,就着手把它不仅仅用来书写抽象名词,而且还用在其他许多方面。他们把它用来书写构成语法词尾的音节或字母。例如,要给英语中的常见音节-tion画出一幅图来可不那么容易,但我们却能为同音动词shun(避开)画出一幅示意图来。用语音来表达的符号也被用来“拼写”较长的词,成为一系列的画面,每一个画面描绘一个音节的发音。这就好像一个说英语的人在写believe(相信)这个词时先画一只蜜蜂(bee)再在后面画一片树叶(leaf)一样。语音符号也使造字的人能够用相同的图形符号来代表一组相关的词(如tooth〔牙齿〕、speech〔说话〕和speaker〔说话者〕),但要解决歧义问题,就得加上一个语音表达符号(如为two〔二〕、each〔每个〕和peak〔山峰〕选择符号)。

Thus, Sumerian writing came to consist of a complex mixture of three types of signs: logograms, referring to a whole word or name; phonetic signs, used in effect for spelling syllables, letters, grammatical elements, or parts of words; and determinatives, which were not pronounced but were used to resolve ambiguities. Nevertheless, the phonetic signs in Sumerian writing fell far short of a complete syllabary or alphabet. Some Sumerian syllables lacked any written signs; the same sign could be pronounced in different ways; and the same sign could variously be read as a word, a syllable, or a letter.

因此,苏美尔文字最后成了3种符号的一种复杂的组合:语标,指称一个完整的词或名字;语音符号,实际上被用来拼写音节、字母、语法成分或部分的词;和义符,不发音,只用来解决歧义问题。尽管如此,苏美尔文字中的语言符号还远远没有达到一种完备的音节表或字母表的标准。苏美尔语的有些音节没有任何书写符号;同一个符号可能有不同的发音;同一个符号可能有各种不同的读法,可以读作一个词、一个音节或一个字母。

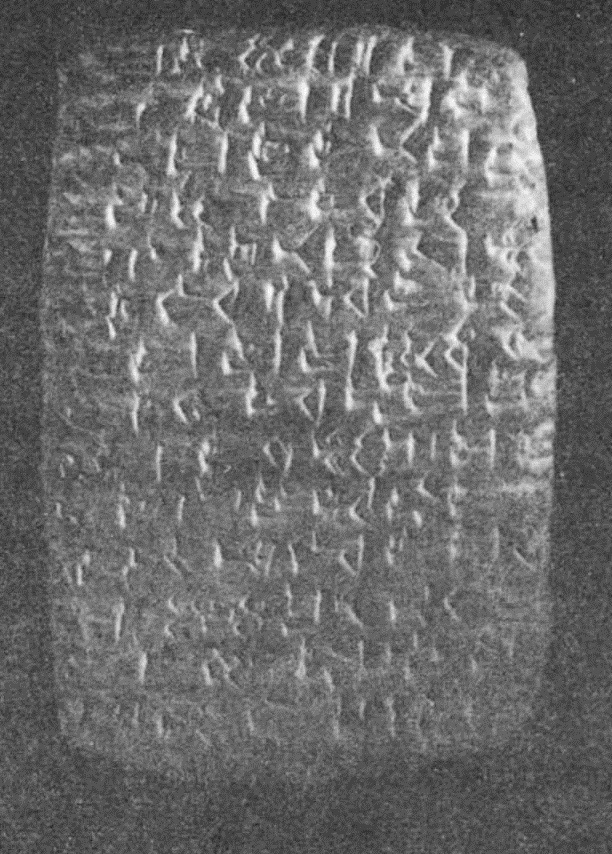

An example of Babylonian cuneiform writing, derived ultimately from Sumerian cuneiform.

巴比伦楔形文字的实例,该文字起源于苏美尔楔形文字。

Besides Sumerian cuneiform, the other certain instance of independent origins of writing in human history comes from Native American societies of Mesoamerica, probably southern Mexico. Mesoamerican writing is believed to have arisen independently of Old World writing, because there is no convincing evidence for pre-Norse contact of New World societies with Old World societies possessing writing. In addition, the forms of Mesoamerican writing signs were entirely different from those of any Old World script. About a dozen Mesoamerican scripts are known, all or most of them apparently related to each other (for example, in their numerical and calendrical systems), and most of them still only partially deciphered. At the moment, the earliest preserved Mesoamerican script is from the Zapotec area of southern Mexico around 600 B.C., but by far the best-understood one is of the Lowland Maya region, where the oldest known written date corresponds to A.D. 292.

除了苏美尔楔形文字外,人类历史上另一个独立发明文字的确然无疑的例子,来自中美洲(可能是墨西哥南部)的印第安社会。有人认为,中美洲文字的出现与旧大陆的文字没有关系,因为没有任何令人信服的证据可以证明在古挪威人之前新大陆的社会就已同拥有文字的旧大陆的社会有了接触。而且,从形式来看,中美洲的书写符号也完全不同于旧大陆的任何一种文字。已知的中美洲文字约有十几种,其中全部或大部分显然有亲缘关系(例如,在它们的数字系统和历法系统方面),它们大多数仍然只是部分得到破译。目前,中美洲保存下来的最早的文字,来自公元前600年左右墨西哥南部的萨波特克地区,但迄今了解得最多的则是马雅人居住的低地地区的文字,那里已知最早的有文字记录的年代相当于公元292年。

Despite its independent origins and distinctive sign forms, Maya writing is organized on principles basically similar to those of Sumerian writing and other western Eurasian writing systems that Sumerian inspired. Like Sumerian, Maya writing used both logograms and phonetic signs. Logograms for abstract words were often derived by the rebus principle. That is, an abstract word was written with the sign for another word pronounced similarly but with a different meaning that could be readily depicted. Like the signs of Japan's kana and Mycenaean Greece's Linear B syllabaries, Maya phonetic signs were mostly signs for syllables of one consonant plus one vowel (such as ta, te, ti, to, tu). Like letters of the early Semitic alphabet, Maya syllabic signs were derived from pictures of the object whose pronunciation began with that syllable (for example, the Maya syllabic sign “ne” resembles a tail, for which the Maya word is neh).

尽管马雅文字是独立发明出来并且具有与众不同的符号形式,但它的组成原则基本上类似于苏美尔文字,也类似于受苏美尔文字启发的欧亚大陆西部其他一些书写系统。同苏美尔文字一样,马雅文字也利用语标和语言符号。代表抽象词的语标通常是根据画谜原则而发明出来的。就是说,一个抽象的词可以用代表另一个词的符号写出来,这个词发音相同,但具有一种不同的然而可以容易画出来的意思。同日本的假名符号和迈锡尼时代希腊的B类线形文字音节表一样,马雅文的语音符号多半是由一个辅音和一个元音构成的音节符号(如ta,te,ti,to,tu)。同早期闪语[3]字母表中的字母一样,马雅文的音节符号来自对所指称事物所画的图像,而对这个事物的发音就是以那个音节开始(例如,马雅文的音节符号“ne”像一个尾巴,而马雅文中表示尾巴的词就是neh)。

All of these parallels between Mesoamerican and ancient western Eurasian writing testify to the underlying universality of human creativity. While Sumerian and Mesoamerican languages bear no special relation to each other among the world's languages, both raised similar basic issues in reducing them to writing. The solutions that Sumerians invented before 3000 B.C. were reinvented, halfway around the world, by early Mesoamerican Indians before 600 B.C.

中美洲文字同欧亚大陆西部古代文字的所有这些相似之处,证明了人类创造力的根本普遍性。虽然在全世界的语言中,苏美尔人的语言和中美洲的语言彼此并没有什么特别的关系,但两者在把语言化为文字方面都提出了一些类似的基本问题。苏美尔人在公元前3000年前首创的解决办法,又在公元前600年前隔着半个地球被早期的中美洲印第安人重新创造出来。

17世纪初印度次大陆拉贾斯坦或古吉拉特画派的一幅画。画上文字与其他大多数现代印度文字一样,源自古印度的婆罗门文字。这种古印度文字可能是由于公元前7世纪左右阿拉姆语字母的思想传播而产生的。印度文字吸收了阿拉姆语字母的原则,但独立地发明了字母形式、字母顺序和对元音的处理,而没有采用蓝图复制的办法。

WITH THE POSSIBLE exceptions of the Egyptian, Chinese, and Easter Island writing to be considered later, all other writing systems devised anywhere in the world, at any time, appear to have been descendants of systems modified from or at least inspired by Sumerian or early Mesoamerican writing. One reason why there were so few independent origins of writing is the great difficulty of inventing it, as we have already discussed. The other reason is that other opportunities for the independent invention of writing were preempted by Sumerian or early Mesoamerican writing and their derivatives.

埃及、中国和复活节岛的文字是可能的例外,留待以后讨论。世界上任何地方任何时候发明出来的所有其他书写系统,似乎都是从一些书写系统派生出来的,这些书写系统或是把苏美尔文字或早期中美洲文字加以修改后为己所用,或至少是受到它们的启发而自行创造出来的。独立发明出来的文字何以如此之少,一个原因是发明文字极其困难,这一点我们已经讨论过了。另一个原因是独立发明文字的其他机会被苏美尔文字或早期中美洲文字以及它们的派生文字抢先得去了。

We know that the development of Sumerian writing took at least hundreds, possibly thousands, of years. As we shall see, the prerequisites for those developments consisted of several features of human society that determined whether a society would find writing useful, and whether the society could support the necessary specialist scribes. Many other human societies besides those of the Sumerians and early Mexicans—such as those of ancient India, Crete, and Ethiopia—evolved these prerequisites. However, the Sumerians and early Mexicans happened to have been the first to evolve them in the Old World and the New World, respectively. Once the Sumerians and early Mexicans had invented writing, the details or principles of their writing spread rapidly to other societies, before they could go through the necessary centuries or millennia of independent experimentation with writing themselves. Thus, that potential for other, independent experiments was preempted or aborted.

我们知道,苏美尔文字的形成至少花去了几百年也许是几千年时间。我们还将看到,文字形成的先决条件是由人类社会的几个特点组成的,正是这些特点决定了一个社会是否会认为文字有用,以及这个社会是否能养活那些专职的抄写员。除了苏美尔人的社会和早期墨西哥人的社会外,其他许多人类社会——如古代印度的社会、克里特岛的社会和埃塞俄比亚的社会——也有了这样的先决条件。然而,苏美尔人和早期墨西哥人碰巧分别是旧大陆和新大陆最早有了这些先决条件的人。一旦苏美尔人和早期墨西哥人发明出文字,他们的文字的细节和原则迅速传播到其他社会,它们可以不必再用几百年甚或几千年的时间去进行造字的实验。因此,其他一些独立的造字实验的可能性就被取消或中止了。

The spread of writing has occurred by either of two contrasting methods, which find parallels throughout the history of technology and ideas. Someone invents something and puts it to use. How do you, another would-be user, then design something similar for your own use, knowing that other people have already got their own model built and working?

文字是通过两种截然不同的方法中的任何一种去传播的,这两种方法在整个技术史和思想史中都可以找到先例。有人发明了一样东西并投入了使用。那么,你作为另一个未来的使用者,既然知道别人已经建造了他们自己的原型并使其发生作用,你又为何要为自己的使用而去设计相同的东西呢?

Such transmission of inventions assumes a whole spectrum of forms. At the one end lies “blueprint copying,” when you copy or modify an available detailed blueprint. At the opposite end lies “idea diffusion,” when you receive little more than the basic idea and have to reinvent the details. Knowing that it can be done stimulates you to try to do it yourself, but your eventual specific solution may or may not resemble that of the first inventor.

此类发明的传播形式多种多样。一头是“蓝图复制”,就是对现有的一幅详尽的蓝图进行复制或修改。另一头是“思想传播”,就是仅仅把基本思想接受过来,然后必须去重新创造细节。知道这能够做到,就会激励你自己努力去干,但你最终的具体解决办法可能像也可能不像第一个发明者的解决办法。

To take a recent example, historians are still debating whether blueprint copying or idea diffusion contributed more to Russia's building of an atomic bomb. Did Russia's bomb-building efforts depend critically on blueprints of the already constructed American bomb, stolen and transmitted to Russia by spies? Or was it merely that the revelation of America's A-bomb at Hiroshima at last convinced Stalin of the feasibility of building such a bomb, and that Russian scientists then reinvented the principles in an independent crash program, with little detailed guidance from the earlier American effort? Similar questions arise for the history of the development of wheels, pyramids, and gunpowder. Let's now examine how blueprint copying and idea diffusion contributed to the spread of writing systems.

举一个最近的例子。历史学家们仍然在争论:蓝图复制或思想传播,到底哪一个对俄国造成原子弹贡献更大。俄国制造原子弹的努力,是否决定性地依赖于由间谍窃取后送到俄国去的已经造好的美国原子弹蓝图?或者这仅仅是美国原子弹在广岛爆炸的启示终于使斯大林相信制造这样的炸弹是可能的,然后由俄国科学家重新创造出用于一项独立的应急计划的原则,而很少从此前美国的努力中得到详尽的指导?对于轮子、金字塔和火药的发展史也存在同样的问题。现在让我们考察一下蓝图复制和思想传播是怎样帮助书写系统的传播的。

TODAY, PROFESSIONAL LINGUISTS design writing systems for unwritten languages by the method of blueprint copying. Most such tailor-made systems modify existing alphabets, though some instead design syllabaries. For example, missionary linguists are working on modified Roman alphabets for hundreds of New Guinea and Native American languages. Government linguists devised the modified Roman alphabet adopted in 1928 by Turkey for writing Turkish, as well as the modified Cyrillic alphabets designed for many tribal languages of Russia.

今天,一些专业语言学家用蓝图复制法为一些没有文字的语言设计书写系统。这种根据特定需要设计的系统,大多数是把现有字母表拿来加以修改,虽然有些也设计出了音节表。例如,一些身为传教士的语言学家,通过修改罗马字母为数以百计的新几内亚和印第安语言设计文字。政府的语言学家不但为俄罗斯的许多部落语言设计出经过修改的西里尔字母,而且也设计出经过修改的罗马字母,于1928年被土耳其采用来书写土耳其语。

In a few cases, we also know something about the individuals who designed writing systems by blueprint copying in the remote past. For instance, the Cyrillic alphabet itself (the one still used today in Russia) is descended from an adaptation of Greek and Hebrew letters devised by Saint Cyril, a Greek missionary to the Slavs in the ninth century A.D. The first preserved texts for any Germanic language (the language family that includes English) are in the Gothic alphabet created by Bishop Ulfilas, a missionary living with the Visigoths in what is now Bulgaria in the fourth century A.D. Like Saint Cyril's invention, Ulfilas's alphabet was a mishmash of letters borrowed from different sources: about 20 Greek letters, about five Roman letters, and two letters either taken from the runic alphabet or invented by Ulfilas himself. Much more often, we know nothing about the individuals responsible for devising famous alphabets of the past. But it's still possible to compare newly emerged alphabets of the past with previously existing ones, and to deduce from letter forms which existing ones served as models. For the same reason, we can be sure that the Linear B syllabary of Mycenaean Greece had been adapted by around 1400 B.C. from the Linear A syllabary of Minoan Crete.

有时候,对于那些在遥远的过去依靠蓝图复制而设计出书写系统的人,我们也有所了解。例如,西里尔字母(今天仍在俄国使用)是公元9世纪时向斯拉夫人传教的希腊传教士圣西里尔通过改造希腊文和希伯来文字母而设计出来的。日耳曼语(包括英语在内的语族)保存完好的最早文本是用乌尔斐拉斯主教创造的哥特文字母写的。乌尔斐拉斯是一个传教士,于公元4世纪同西哥特人一起生活在今天的保加利亚。同圣西里尔的发明一样,乌尔斐拉斯的字母表是从其他来源借用的字母的大杂烩:有大约20个希腊字母,大约5个罗马字母,还有两个字母或是取自如尼文[4]字母,或是他自己创造的。更多的时候,对于那些发明著名的古代字母的人,我们则一无所知。但仍有可能把新出现的古代字母同以前存在的字母加以比较,并从字母的形式推断出是哪些现有的字母被用作模本。由于同样的原因,我们可以肯定,迈锡尼时代希腊的B类线型音节文字是在公元前1400年左右从克里特岛的A类线形音节文字改造而来的。

At all of the hundreds of times when an existing writing system of one language has been used as a blueprint to adapt to a different language, some problems have arisen, because no two languages have exactly the same sets of sounds. Some inherited letters or signs may simply be dropped, when the sounds that those letters represent in the lending language do not exist in the borrowing language. For example, Finnish lacks the sounds that many other European languages express by the letters b, c, f, g, w, x, and z, so the Finns dropped these letters from their version of the Roman alphabet. There has also been a frequent reverse problem, of devising letters to represent “new” sounds present in the borrowing language but absent in the lending language. That problem has been solved in several different ways: such as using an arbitrary combination of two or more letters (like the English th to represent a sound for which the Greek and runic alphabets used a single letter); adding a small distinguishing mark to an existing letter (like the Spanish tilde , the German umlaut , and the proliferation of marks dancing around Polish and Turkish letters); co-opting existing letters for which the borrowing language had no use (such as modern Czechs recycling the letter c of the Roman alphabet to express the Czech sound ts); or just inventing a new letter (as our medieval ancestors did when they created the new letters j, u, and w).

把一种语言的现有书写系统用作蓝图使之适应另一种语言,在几百次这样做的过程中总会出现一些问题,因为没有两种语言的发音是完全相同的。原来的字母和符号有些被舍弃了,如果在借出语言中的那些字母所代表的发音在借入语言中是不存在的,就会出现这种情况。例如,芬兰语中没有其他欧洲语言用b、c、f、g、w、x和z所代表的音,因此芬兰人就从他们的经过改造的罗马字母中舍弃了这些字母。还有一个经常出现的相反问题,即设计出一些字母来代表为借入语言所有而为借出语言所无的一些“新的”发音。这个问题以几种不同的方式获得了解决:如利用一个由两个或两个以上字母构成的任意组合(如英语中的th代表在希腊语和如尼语中只用一个字母代表的音);给一个现有的字母加上一个区别性的记号(如西班牙语字母的腭化符号,德语字母的变音符号,以及那些多出来的在波兰语和土耳其语字母周围跳舞的记号);征用借入语言中用不着的字母(如现代捷克语把罗马字母C重新起用来表示捷克语中的ts音);或者干脆创造出一个新的字母(就像我们中世纪的祖先在创造j、u和w这些新字母时所做的那样)。

The Roman alphabet itself was the end product of a long sequence of blueprint copying. Alphabets apparently arose only once in human history: among speakers of Semitic languages, in the area from modern Syria to the Sinai, during the second millennium B.C. All of the hundreds of historical and now existing alphabets were ultimately derived from that ancestral Semitic alphabet, in a few cases (such as the Irish ogham alphabet) by idea diffusion, but in most by actual copying and modification of letter forms.

罗马字母本身就是长长的一系列蓝图复制的终端产品。在人类历史上,字母显然只产生过一次:是在公元前第二个1000年中从现代叙利亚到西奈半岛这个地区内说闪语的人当中产生的。历史上的和现行的几百种字母,追本溯源全都来自闪语字母这个老祖宗,有些(如爱尔兰的欧甘字母[5])是思想传播的结果,但大多数则是通过对字母形式的实际复制和修改而产生的。

That evolution of the alphabet can be traced back to Egyptian hieroglyphs, which included a complete set of 24 signs for the 24 Egyptian consonants. The Egyptians never took the logical (to us) next step of discarding all their logograms, determinatives, and signs for pairs and trios of consonants, and using just their consonantal alphabet. Starting around 1700 B.C., though, Semites familiar with Egyptian hieroglyphs did begin to experiment with that logical step.

字母的这种演化可以追溯到埃及象形文字,这种文字包含代表埃及语24个辅音的全套24个符号。埃及人没有采取(在我们看来)合乎逻辑的下一步,即抛弃他们所有的语标、义符和代表双辅音和三辅音的符号,而只使用他们的辅音字母。然而,从大约公元前1700年开始,一些精通埃及象形文字的闪米特人着手对这合乎逻辑的一步进行试验。

Restricting signs to those for single consonants was only the first of three crucial innovations that distinguished alphabets from other writing systems. The second was to help users memorize the alphabet by placing the letters in a fixed sequence and giving them easy-to-remember names. Our English names are mostly meaningless monosyllables (“a,” “bee,” “cee,” “dee,” and so on). But the Semitic names did possess meaning in Semitic languages: they were the words for familiar objects ('aleph = ox, beth = house, gimel = camel, daleth = door, and so on). These Semitic words were related “acrophonically” to the Semitic consonants to which they refer: that is, the first letter of the word for the object was also the letter named for the object ('a, b, g, d, and so on). In addition, the earliest forms of the Semitic letters appear in many cases to have been pictures of those same objects. All these features made the forms, names, and sequence of Semitic alphabet letters easy to remember. Many modern alphabets, including ours, retain with minor modifications that original sequence (and, in the case of Greek, even the letters' original names: alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and so on) over 3,000 years later. One minor modification that readers will already have noticed is that the Semitic and Greek g became the Roman and English c, while the Romans invented a new g in its present position.

规定符号只能用来代表单辅音,这是把字母同其他书写系统区别开来的3大改革中的第一项改革。第二项改革是把字母按照一个固定的顺序排列并给它们起一个容易记住的名称,从而帮助使用者来记住这些字母。我们英语字母的名称多半是没有意义的单音节(“a”、“bee”、“cee”、“dee”,等等)。但闪语字母的名称在闪语中是有意义的:它们都是代表人们所熟悉的事物的词('aleph=牛,beth=房子,gimel=骆驼,daleth=门,等等)。这些闪语词“通过截头表音法”同它们所涉及的闪语辅音发生关系:就是说,代表该事物的词的第一个字母,也就是赋予该事物以名称的那个字母('a、b、g、d,等等)。此外,闪语字母的最早形式在许多情况下似乎都是那些事物的图像。所有这些特点使闪语字母的形式、名称和排列顺序容易记住。许多现代语言的字母,包括我们英语的字母,在3000多年后仍然保留了原来的排列顺序,只是发生了一些小小的改变(就希腊语而言,甚至还保留了字母原来的名称:alpha、beta、gamma、delta,等等)。读者们可能已经注意到的一个小小的改变,是闪语和希腊语字母中的g变成了罗马语和英语字母中的c,而罗马人又在现在的位置上创造出一个新的g。

The third and last innovation leading to modern alphabets was to provide for vowels. Already in the early days of the Semitic alphabet, experiments began with methods for writing vowels by adding small extra letters to indicate selected vowels, or else by dots, lines, or hooks sprinkled over the consonantal letters. In the eighth century B.C. the Greeks became the first people to indicate all vowels systematically by the same types of letters used for consonants. Greeks derived the forms of their vowel letters by “co-opting” five letters used in the Phoenician alphabet for consonantal sounds lacking in Greek.

导致现代语言的字母的第三项也是最后一项改革的,是规定了元音。在闪语字母的早期,已经有人着手对书写元音的方法进行实验,或是另外加上一些小字母来表示特定的元音,或是在辅音字母上加上点、线或钩。在公元前8世纪,希腊人成为用代表辅音的那些字母来系统地表示全部元音的第一个民族。希腊人通过“征用”腓尼基语字母中用来代表为希腊语所无的一些辅音的5个字母而得到他们的元音字母α-∈-η-ι-ο。

From those earliest Semitic alphabets, one line of blueprint copying and evolutionary modification led via early Arabian alphabets to the modern Ethiopian alphabet. A far more important line evolved by way of the Aramaic alphabet, used for official documents of the Persian Empire, into the modern Arabic, Hebrew, Indian, and Southeast Asian alphabets. But the line most familiar to European and American readers is the one that led via the Phoenicians to the Greeks by the early eighth century B.C., thence to the Etruscans in the same century, and in the next century to the Romans, whose alphabet with slight modifications is the one used to print this book. Thanks to their potential advantage of combining precision with simplicity, alphabets have now been adopted in most areas of the modern world.

文字演变的一条路线是对这些最早的闪语字母进行蓝图复制和逐步修改,从而发展成早期的阿拉伯字母,再进而发展成现代的埃塞俄比亚语的字母。还有一条重要得多的路线是经由用于波斯帝国官方文件的阿拉姆语[6]字母,演变为现代的阿拉伯语、希伯来语、印度语和东南亚语言的字母。但欧洲和美国读者最为熟悉的一条演变路线到公元前8世纪初经由腓尼基人到达希腊人,在同一世纪内又从希腊人到达伊特鲁斯坎人[7],又过了一个世纪到达罗马人,罗马人的字母稍经修改就成了英文字母。由于精确和简洁相结合的这种潜在优点,字母如今已在现代世界的大部分地区得到采用。

WHILE BLUEPRINT COPYING and modification are the most straightforward option for transmitting technology, that option is sometimes unavailable. Blueprints may be kept secret, or they may be unreadable to someone not already steeped in the technology. Word may trickle through about an invention made somewhere far away, but the details may not get transmitted. Perhaps only the basic idea is known: someone has succeeded, somehow, in achieving a certain final result. That knowledge may nevertheless inspire others, by idea diffusion, to devise their own routes to such a result.

虽然蓝图的复制和修改是传播技术的最直接的选择,但有时候这种选择不一定能够得到。蓝图可能被隐藏起来,而且不是深于此道的人对蓝图也不一定能够读懂。对于在远处某个地方发明了某个东西,人们可能有所耳闻,但详细情况则可能无从知晓。也许所知道的只是这样的基本思想:某人以某种方法成功地取得了某种最后的成果。然而,知道了这一点,可能就是通过思想传播去启发别人设计他们自己的取得此种成果的途径。

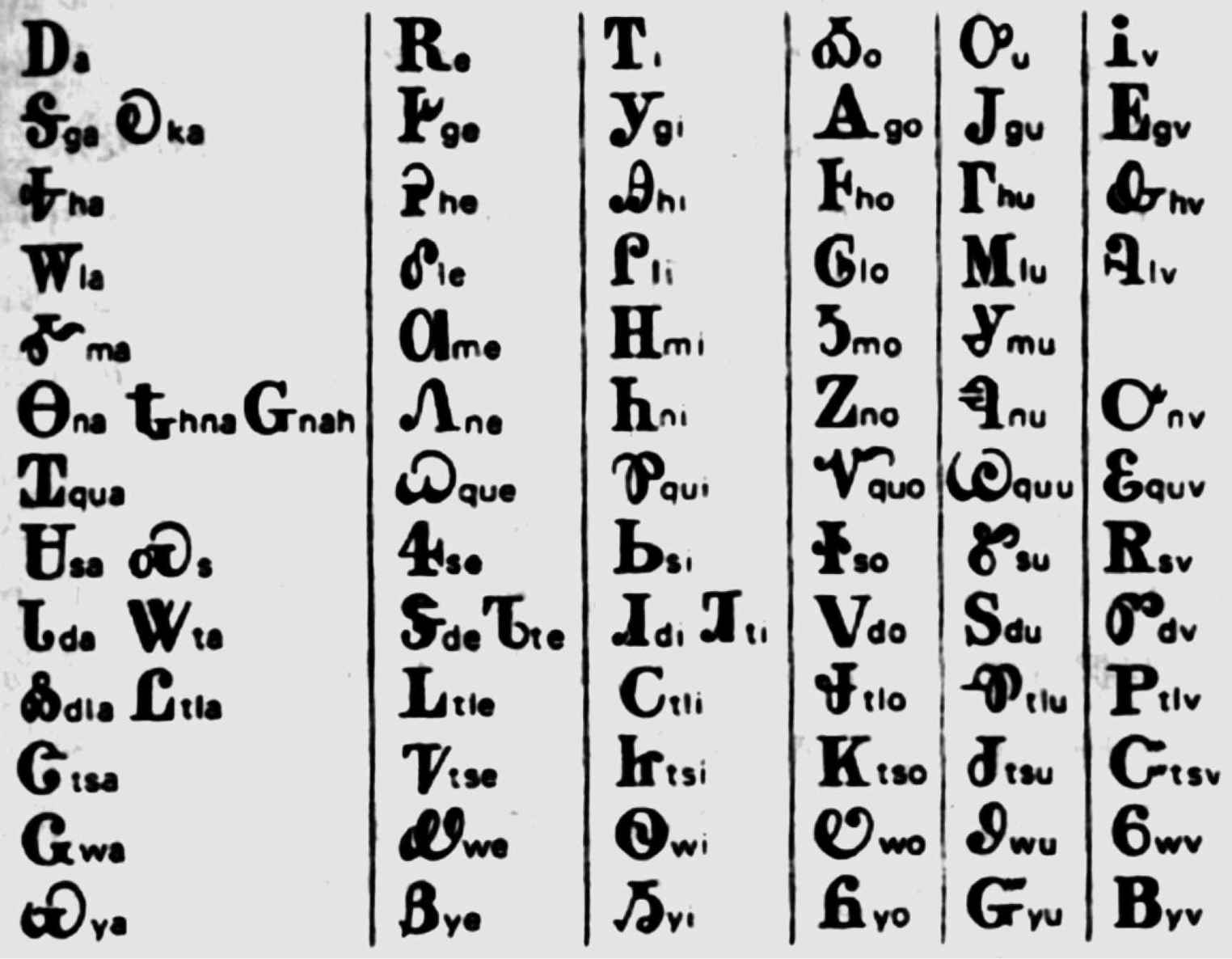

A striking example from the history of writing is the origin of the syllabary devised in Arkansas around 1820 by a Cherokee Indian named Sequoyah, for writing the Cherokee language. Sequoyah observed that white people made marks on paper, and that they derived great advantage by using those marks to record and repeat lengthy speeches. However, the detailed operations of those marks remained a mystery to him, since (like most Cherokees before 1820) Sequoyah was illiterate and could neither speak nor read English. Because he was a blacksmith, Sequoyah began by devising an accounting system to help him keep track of his customers' debts. He drew a picture of each customer; then he drew circles and lines of various sizes to represent the amount of money owed.

文字史上的一个引人注目的例子是:1820年左右阿肯色州的一个名叫塞阔雅的印第安人为了书写切罗基语而发明了音节文字。塞阔雅注意到,白人在纸上做记号,并且用这些记号来记录和复述长篇讲话,能得到很大方便。然而,这些记号的复杂作用对他来说仍是一个谜,因为(同1820年前的大多数切罗基人一样)塞阔雅是个文盲,对英语既不会说,也不会读。因为塞阔雅是个铁匠,他开始时发明了一种记账法帮助他记录顾客的欠账。他给每一个顾客画一幅画;然后他又画了一些大小不一的圆圈和线条来表示所欠钱款的数量。

Around 1810, Sequoyah decided to go on to design a system for writing the Cherokee language. He again began by drawing pictures, but gave them up as too complicated and too artistically demanding. He next started to invent separate signs for each word, and again became dissatisfied when he had coined thousands of signs and still needed more.

1810年左右,塞阔雅决定去为切罗基语设计一种书写系统。他又一次开始画图,但由于画图太复杂,在艺术上要求太高,就放弃了。接下去他为每一个词发明一些单独的符号,但在他创造了几千个符号而仍然不够用时,他又觉得不满意了。

Finally, Sequoyah realized that words were made up of modest numbers of different sound bites that recurred in many different words—what we would call syllables. He initially devised 200 syllabic signs and gradually reduced them to 85, most of them for combinations of one consonant and one vowel.

最后,塞阔雅认识到,词是由一些不同的声音组成的,这些声音在许多不同的词里反复出现——这就是我们所说的音节。他开始时设计出200个音节符号,又逐步减少到85个,大多数符号代表一个辅音和一个元音的组合。

As one source of the signs themselves, Sequoyah practiced copying the letters from an English spelling book given to him by a schoolteacher. About two dozen of his Cherokee syllabic signs were taken directly from those letters, though of course with completely changed meanings, since Sequoyah did not know the English meanings. For example, he chose the shapes D, R, b, h to represent the Cherokee syllables a, e, si, and ni, respectively, while the shape of the numeral 4 was borrowed for the syllable se. He coined other signs by modifying English letters, such as designing the signs  ,

, , and

, and  to represent the syllables yu, sa, and na, respectively. Still other signs were entirely of his creation, such as

to represent the syllables yu, sa, and na, respectively. Still other signs were entirely of his creation, such as  ,

,  , and

, and  for ho, li, and nu, respectively. Sequoyah's syllabary is widely admired by professional linguists for its good fit to Cherokee sounds, and for the ease with which it can be learned. Within a short time, the Cherokees achieved almost 100 percent literacy in the syllabary, bought a printing press, had Sequoyah's signs cast as type, and began printing books and newspapers.

for ho, li, and nu, respectively. Sequoyah's syllabary is widely admired by professional linguists for its good fit to Cherokee sounds, and for the ease with which it can be learned. Within a short time, the Cherokees achieved almost 100 percent literacy in the syllabary, bought a printing press, had Sequoyah's signs cast as type, and began printing books and newspapers.

一位小学老师给了塞阔雅一本英语单词拼写课本,他于是就用这本书来练习抄写字母,这些字母也就成了他的符号的一个来源。他的切罗基语音节符号大约有二十几个直接取自英语字母,当然意义完全改变了,因为塞阔雅并不知道它们在英语中的含意。例如,他挑出D、R、b和h这些符号来分别代表切罗基语的音节a、e、si和ni,而数字4这个符号则被借用来代表音节se。他把一些英语字母加以改变从而创造出其他一些符号,例如他设计出符号  、

、 和

和  来分别代表音节yu、sa和na。还有一些符号则完全是他自己的创造,如分别代表ho、li和nu的

来分别代表音节yu、sa和na。还有一些符号则完全是他自己的创造,如分别代表ho、li和nu的  、

、 和

和  。塞阔雅的音节文字得到专业语言学家的普遍赞赏,因为它非常切合切罗基语的发音,同时学起来也很容易。在很短时间内,切罗基人几乎100%地学会了这种音节文字,他们买来了印刷机,把塞阔雅的符号铸成铅字,并开始印起书报来。

。塞阔雅的音节文字得到专业语言学家的普遍赞赏,因为它非常切合切罗基语的发音,同时学起来也很容易。在很短时间内,切罗基人几乎100%地学会了这种音节文字,他们买来了印刷机,把塞阔雅的符号铸成铅字,并开始印起书报来。

塞阔雅发明的代表切罗基语音节的一组符号

Cherokee writing remains one of the best-attested examples of a script that arose through idea diffusion. We know that Sequoyah received paper and other writing materials, the idea of a writing system, the idea of using separate marks, and the forms of several dozen marks. Since, however, he could neither read nor write English, he acquired no details or even principles from the existing scripts around him. Surrounded by alphabets he could not understand, he instead independently reinvented a syllabary, unaware that the Minoans of Crete had already invented another syllabary 3,500 years previously.

切罗基文字始终是关于思想传播产生文字的得到最充分证明的例子之一。我们知道,塞阔雅得到了纸和其他书写材料,得到了关于书写系统的思想、利用不同符号的思想,并得到了几十种记号形式。然而,由于他对英语既不能读,也不能写,所以他不能从周围现有的各种文字中得到关于造字的细节,甚至也得不到关于造字的原则。虽然他周围语言的字母都是他所不了解的,但他却在不知道3500年前克里特岛已经创造出另一种音节文字的情况下独立地重新创造出一种音节文字。

SEQUOYAH'S EXAMPLE CAN serve as a model for how idea diffusion probably led to many writing systems of ancient times as well. The han'gul alphabet devised by Korea's King Sejong in A.D. 1446 for the Korean language was evidently inspired by the block format of Chinese characters and by the alphabetic principle of Mongol or Tibetan Buddhist writing. However, King Sejong invented the forms of han'gul letters and several unique features of his alphabet, including the grouping of letters by syllables into square blocks, the use of related letter shapes to represent related vowel or consonant sounds, and shapes of consonant letters that depict the position in which the lips or tongue are held to pronounce that consonant. The ogham alphabet used in Ireland and parts of Celtic Britain from around the fourth century A.D. similarly adopted the alphabetic principle (in this case, from existing European alphabets) but again devised unique letter forms, apparently based on a five-finger system of hand signals.

塞阔雅的例子也可被用作说明思想传播如何可能导致古代许多书写系统的样本。公元1446年朝鲜李朝国王世宗为朝鲜语设计的谚文字母,显然受到了中国方块字的启发,同时也受到了蒙古和西藏佛教经文的字母表音原则的启发。然而,世宗国王创造了谚文字母的形式和他的字母的几个独一无二的特点,包括用音节把字母组成方块,用相关的字母形状来代表相关的元音或辅音,以及用描写嘴唇和舌头位置的辅音字母的特有形状来发那个辅音。从公元4世纪左右在爱尔兰和说凯尔特语的不列颠部分地区使用的欧甘字母,同样采用了字母表音原则(此时已有现成的欧洲字母可以采用),但也发明了独一无二的字母形式,而这种形式显然是以手势语的五指法为基础的。

A Korean sign illustrating the remarkable han'gul writing system. Each square block represents a syllable, but each component sign within the block represents a letter.

显示与众不同的谚文书写系统的朝鲜文原文(诗:《山丘上的花》,金素月[8]著)。每一个方块代表一个音节,而方块内的每一个组成符号代表一个字母。

We can confidently attribute the han'gul and ogham alphabets to idea diffusion rather than to independent invention in isolation, because we know that both societies were in close contact with societies possessing writing and because it is clear which foreign scripts furnished the inspiration. In contrast, we can confidently attribute Sumerian cuneiform and the earliest Mesoamerican writing to independent invention, because at the times of their first appearances there existed no other script in their respective hemispheres that could have inspired them. Still debatable are the origins of writing on Easter Island, in China, and in Egypt.

我们可以有把握地把谚文字母和欧甘字母的出现归之于思想的传播,而不是闭门造车式的独立创造,因为我们知道这两个社会与拥有文字的社会保持着密切的交往,同时也因为显而易见是哪些外国文字提供了灵感。相比之下,我们也可以有把握地把苏美尔的楔形文字和中美洲的最早文字归之于独立创造,因为在它们首次出现时,在它们各自所在的半球范围内,不存在任何可以给它们以启发的其他文字。仍然可以争论的是复活节岛、中国和埃及的文字起源问题。

The Polynesians living on Easter Island, in the Pacific Ocean, had a unique script of which the earliest preserved examples date back only to about A.D. 1851, long after Europeans reached Easter in 1722. Perhaps writing arose independently on Easter before the arrival of Europeans, although no examples have survived. But the most straightforward interpretation is to take the facts at face value, and to assume that Easter Islanders were stimulated to devise a script after seeing the written proclamation of annexation that a Spanish expedition handed to them in the year 1770.

生活在太平洋中复活节岛上的波利尼西亚人有一种独特的文字,这种文字保存完好的最早样本只可追溯到公元1851年左右,也就是在欧洲人于1722年到达该岛之后很久。也许,在欧洲人到达之前,文字就已在复活节岛独立出现了,虽然没有任何样本保存下来。但是,最直截了当的解释就是不妨对一些事实信以为真,假定1770年一支西班牙探险队向复活节岛居民递交了书面的并吞声明,正是看了这个声明才促使岛上居民去发明一种文字。

As for Chinese writing, first attested around 1300 B.C. but with possible earlier precursors, it too has unique local signs and some unique principles, and most scholars assume that it evolved independently. Writing had developed before 3000 B.C. in Sumer, 4,000 miles west of early Chinese urban centers, and appeared by 2200 B.C. in the Indus Valley, 2,600 miles west, but no early writing systems are known from the whole area between the Indus Valley and China. Thus, there is no evidence that the earliest Chinese scribes could have had knowledge of any other writing system to inspire them.

至于中国文字,最早有实物证明的是在公元前1300年左右,但也可能还有更早的。中国文字也具有为本地所独有的符号和某些组合原则,所以大多数学者认为,它也是独立发展起来的。文字于公元前3000年在中国早期城市中心以西4000英里的苏美尔发展起来,并在不迟于公元前2200年时在这些城市中心以西2600英里的印度河河谷出现,但在印度河河谷和中国之间的整个地区没有听说过存在早期的书写系统。因此,没有证据可以说明中国最早的抄写员已经知道了其他任何可以给他们以启发的书写系统。

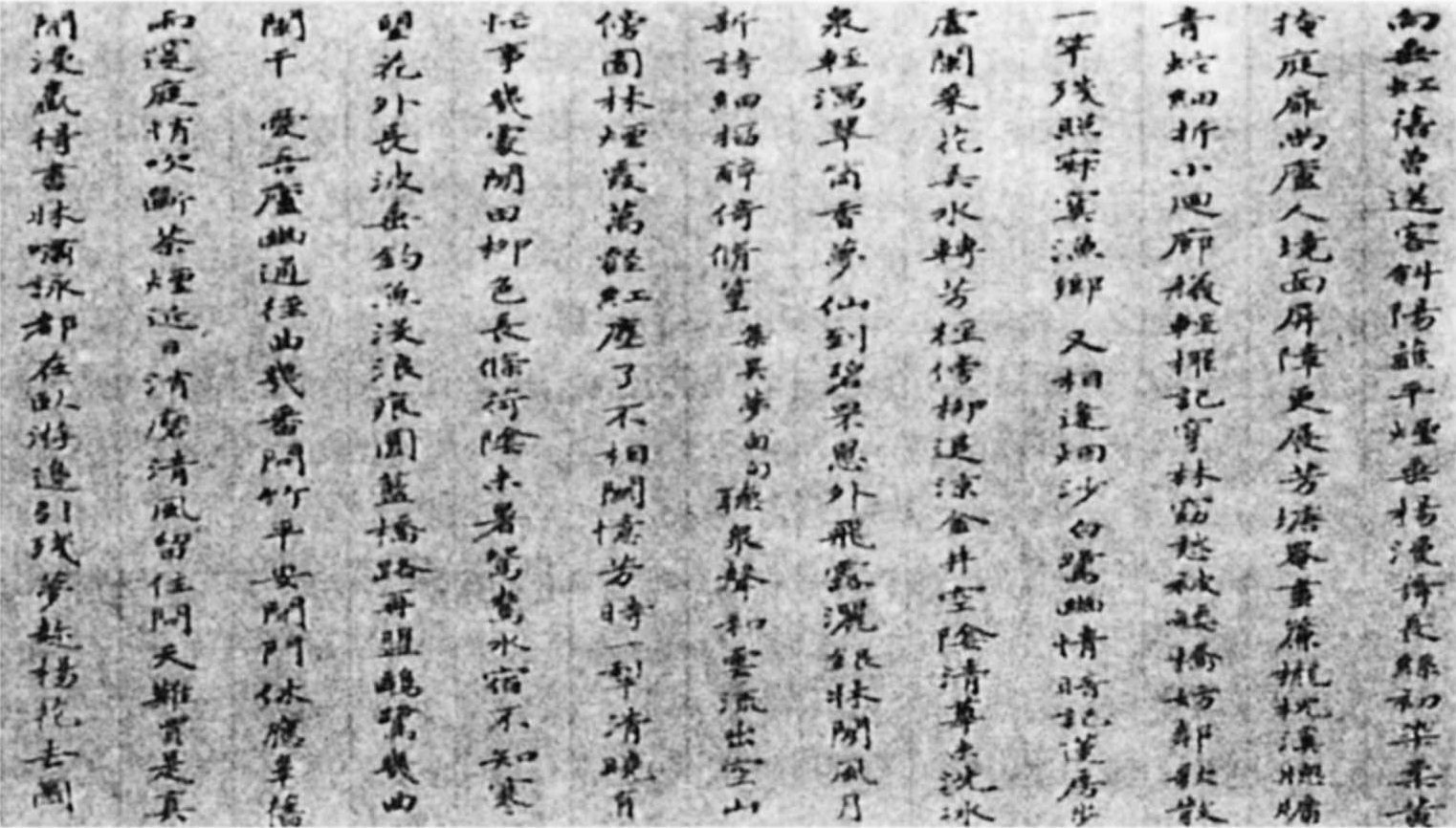

An example of Chinese writing: a handscroll by Wu Li, from A.D. 1679.

中国文字举例:吴历[9]于1679年所书手卷

Egyptian hieroglyphics, the most famous of all ancient writing systems, are also usually assumed to be the product of independent invention, but the alternative interpretation of idea diffusion is more feasible than in the case of Chinese writing. Hieroglyphic writing appeared rather suddenly, in nearly full-blown form, around 3000 B.C. Egypt lay only 800 miles west of Sumer, with which Egypt had trade contacts. I find it suspicious that no evidence of a gradual development of hieroglyphs has come down to us, even though Egypt's dry climate would have been favorable for preserving earlier experiments in writing, and though the similarly dry climate of Sumer has yielded abundant evidence of the development of Sumerian cuneiform for at least several centuries before 3000 B.C. Equally suspicious is the appearance of several other, apparently independently designed, writing systems in Iran, Crete, and Turkey (so-called proto-Elamite writing, Cretan pictographs, and Hieroglyphic Hittite, respectively), after the rise of Sumerian and Egyptian writing. Although each of those systems used distinctive sets of signs not borrowed from Egypt or Sumer, the peoples involved could hardly have been unaware of the writing of their neighboring trade partners.

在所有古代书写系统中最有名的埃及象形文字,通常也被认为是独立创造的产物,但如认为埃及文字和中国文字不同,是思想传播的结果,这种解释似乎更为合理。象形文字于公元3000年左右以几乎完全成熟的形式相当突然地出现。埃及在苏美尔西面仅仅800英里,埃及和苏美尔也一直有贸易往来。使我感到可疑的是,竟然没有关于象形文字逐步发展的任何证据流传下来,尽管埃及的干燥气候可能会有利于保存更早的文字实验成果,尽管苏美尔同样干燥的气候至少在公元前3000年前的几个世纪中已经产生了关于苏美尔楔形文字发展的丰富证据。同样可疑的是,在苏美尔文字和埃及文字出现之后,又在伊朗、克里特和土耳其出现了其他几种显然独立设计出来的书写系统(分别为所谓原始埃兰语文字、克里特形象文字和赫梯象形文字)。虽然这些书写系统的每一种所使用的一套特殊的符号,都不是从埃及或苏美尔借用的,但发明这些书写系统的民族几乎是不可能不知道他们邻近的贸易伙伴的文字的。

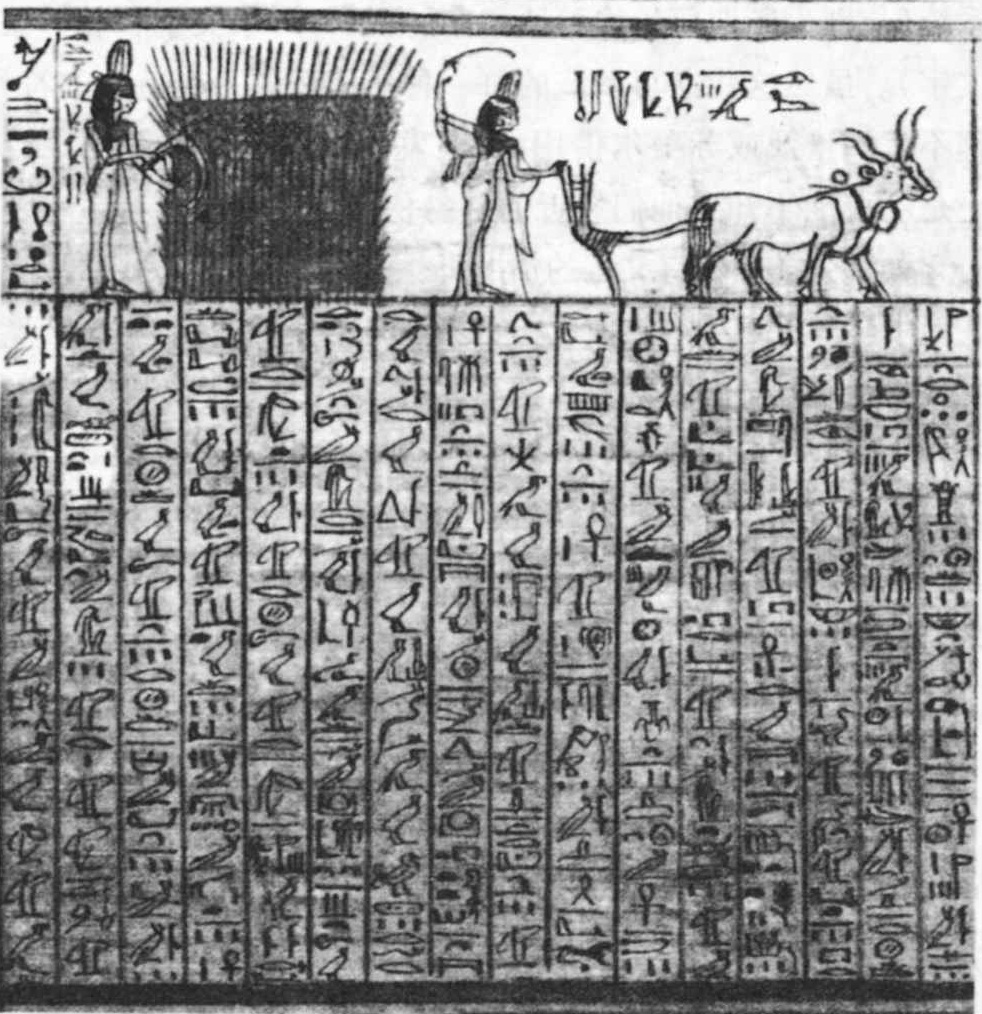

An example of Egyptian hieroglyphs: the funerary papyrus of Princess Entiuny.

埃及象形文字举例:安提优-尼王妃葬礼用纸草卷轴。

It would be a remarkable coincidence if, after millions of years of human existence without writing, all those Mediterranean and Near Eastern societies had just happened to hit independently on the idea of writing within a few centuries of each other. Hence a possible interpretation seems to me idea diffusion, as in the case of Sequoyah's syllabary. That is, Egyptians and other peoples may have learned from Sumerians about the idea of writing and possibly about some of the principles, and then devised other principles and all the specific forms of the letters for themselves.

如果人类在没有文字的情况下生存了几百万年之后,所有这些地中海和近东社会在彼此相距不过几百年的时间内,碰巧竟各自独立地偶然想到发明文字这个主意,这可能是一个非同一般的巧合。因此,在我看来,一个可能的解释就是思想传播,就像塞阔雅的情形一样。这就是说,埃及人和其他民族可能已从苏美尔人那里了解到发明文字的思想,可能还了解到某些造字原则,然后又为自己发明了另外一些原则和全部字母的特有形式。

LET US NOW return to the main question with which we began this chapter: why did writing arise in and spread to some societies, but not to many others? Convenient starting points for our discussion are the limited capabilities, uses, and users of early writing systems.

现在,让我们再回到本章开始时的那个主要问题:为什么文字在某些社会出现并向某些社会传播,但不向其他许多社会传播?我们讨论的方便的起始点是早期书写系统的有限容量、有限用途和有限使用者。

Early scripts were incomplete, ambiguous, or complex, or all three. For example, the oldest Sumerian cuneiform writing could not render normal prose but was a mere telegraphic shorthand, whose vocabulary was restricted to names, numerals, units of measure, words for objects counted, and a few adjectives. That's as if a modern American court clerk were forced to write “John 27 fat sheep,” because English writing lacked the necessary words and grammar to write “We order John to deliver the 27 fat sheep that he owes to the government.” Later Sumerian cuneiform did become capable of rendering prose, but it did so by the messy system that I've already described, with mixtures of logograms, phonetic signs, and unpronounced determinatives totaling hundreds of separate signs. Linear B, the writing of Mycenaean Greece, was at least simpler, being based on a syllabary of about 90 signs plus logograms. Offsetting that virtue, Linear B was quite ambiguous. It omitted any consonant at the end of a word, and it used the same sign for several related consonants (for instance, one sign for both l and r, another for p and b and ph, and still another for g and k and kh). We know how confusing we find it when native-born Japanese people speak English without distinguishing l and r: imagine the confusion if our alphabet did the same while similarly homogenizing the other consonants that I mentioned! It's as if we were to spell the words “rap,” “lap,” “lab,” and “laugh” identically.

早期文字不完整、不明确或复杂难懂,或三者都有。例如,最早的苏美尔楔形文字还不能连缀成文,而只是一种电报式的简略表达方式,它的词汇只限于一些名字、数字、测量单位、代表数过的物件的词以及几个形容词。这情形就好像一个现代的美国法院书记员由于英语里没有必要的词和语法,无法写出“我们命令约翰把欠政府的27头肥羊交来”这样的话,而只能写成“约翰27头肥羊”。后来,苏美尔楔形文字能够写出散文来,但也显得杂乱无章,正如我曾经描绘过的那样,是语标、音符和总数多达几百个不同符号的不发音的义符的大杂烩。迈锡尼时代的希腊的B类线形文字至少要简单一些,因为它根据的是一种大约有90个符号和语标的音节文字。和这个优点相比,B类线形文字的缺点就是很不明确。它把词尾的辅音全都省略,并用同一个符号来代表几个相关的辅音(例如,一个符号代表l和r,另一个符号代表p、b和ph,另有一个符号代表g、k和kh)。我们知道,如果土生土长的日本人连l和r都分不清楚就去讲英语,那会使我们感到多么莫名其妙:请想象一下,如果我们的字母把我刚才提到的其他一些辅音也同样类同起来,那会造成什么样的混乱。这就好像我们把“rap”、“lap”、“lab”和“laugh”这些词拼写成一个词一样。

A related limitation is that few people ever learned to write these early scripts. Knowledge of writing was confined to professional scribes in the employ of the king or temple. For instance, there is no hint that Linear B was used or understood by any Mycenaean Greek beyond small cadres of palace bureaucrats. Since individual Linear B scribes can be distinguished by their handwriting on preserved documents, we can say that all preserved Linear B documents from the palaces of Knossos and Pylos are the work of a mere 75 and 40 scribes, respectively.

一个相关的限制是很少有人学会书写这些早期的文字。只有国王或寺庙雇用的专职抄写员,才掌握关于文字的知识。例如,没有任何迹象表明,除了宫廷官员中很少几个骨干分子外,在迈锡尼时代的希腊人中还有谁使用或了解B类线形文字。由于B类线形文字的各个抄写员可以根据他们留在保存下来的文件上的笔迹区别开来,我们可以说,克诺索斯[10]和派洛斯[11]宫殿保存下来的用B类线形文字抄写的文件分别出自仅仅75个和40个抄写员之手。

The uses of these telegraphic, clumsy, ambiguous early scripts were as restricted as the number of their users. Anyone hoping to discover how Sumerians of 3000 B.C. thought and felt is in for a disappointment. Instead, the first Sumerian texts are emotionless accounts of palace and temple bureaucrats. About 90 percent of the tablets in the earliest known Sumerian archives, from the city of Uruk, are clerical records of goods paid in, workers given rations, and agricultural products distributed. Only later, as Sumerians progressed beyond logograms to phonetic writing, did they begin to write prose narratives, such as propaganda and myths.

对这些简略、笨拙、不明确的早期文字的使用,同它们的使用者的人数一样都受到了限制。任何人如果希望去发现公元前3000年苏美尔人的思想和感情,是注定要失望的。最早的苏美尔文文本只是宫廷和寺庙官员所记的一些毫无感情的账目。在已知最早的乌鲁克城苏美尔档案中,大约90%的刻写板上都是神职人员记下的采购货物、工人配给和农产品分配等事项。只是到了后来,随着苏美人从语标文字逐步过渡到语音文字,他们才开始写作记叙体散文,如宣传资料和神话。

Mycenaean Greeks never even reached that propaganda-and-myths stage. One-third of all Linear B tablets from the palace of Knossos are accountants' records of sheep and wool, while an inordinate proportion of writing at the palace of Pylos consists of records of flax. Linear B was inherently so ambiguous that it remained restricted to palace accounts, whose context and limited word choices made the interpretation clear. Not a trace of its use for literature has survived. The Iliad and Odyssey were composed and transmitted by nonliterate bards for nonliterate listeners, and not committed to writing until the development of the Greek alphabet hundreds of years later.

迈锡尼时代的希腊人甚至没有达到写作宣传资料和神话的阶段。在克诺索斯宫殿出土的全部B类线形文字刻写板中,有三分之一是关于绵羊和羊毛的账目,而在派洛斯宫殿发现的极大部分文字记录的都是亚麻。B类线形文字本来就不明确,所以始终只用来在宫廷中记账,由于有上下文和选词限制的关系,解读起来是很清楚的。关于这种文字用于文学创作,则无迹可寻。《伊利亚特》和《奥德赛》[12]是不识字的行吟诗人为不识字的听众创作而传播开来的,直到几百年后才随着希腊字母的发展而见诸文字。

Similarly restricted uses characterize early Egyptian, Mesoamerican, and Chinese writing. Early Egyptian hieroglyphs recorded religious and state propaganda and bureaucratic accounts. Preserved Maya writing was similarly devoted to propaganda, births and accessions and victories of kings, and astronomical observations of priests. The oldest preserved Chinese writing of the late Shang Dynasty consists of religious divination about dynastic affairs, incised into so-called oracle bones. A sample Shang text: “The king, reading the meaning of the crack [in a bone cracked by heating], said: ‘If the child is born on a keng day, it will be extremely auspicious.'”

同样的使用限制也是早期埃及、中美洲和中国文字的特点。早期的埃及象形文字记录了宗教和国家的宣传材料以及官员们的账目。保存完好的马雅文字也同样专门用于宣传、记录国王的生辰、登基和战争胜利以及祭司的天象观测结果。现存最早的商代晚期的中国文字被用来为朝廷大事占卜吉凶,卜辞就刻写在所谓甲骨上。一个商代文字的样本是:“国王在识读裂纹〔骨头经火灼而产生的裂纹〕的意思后说:‘如果这孩子是在庚日出生的,那将非常吉利。’”

To us today, it is tempting to ask why societies with early writing systems accepted the ambiguities that restricted writing to a few functions and a few scribes. But even to pose that question is to illustrate the gap between ancient perspectives and our own expectations of mass literacy. The intended restricted uses of early writing provided a positive disincentive for devising less ambiguous writing systems. The kings and priests of ancient Sumer wanted writing to be used by professional scribes to record numbers of sheep owed in taxes, not by the masses to write poetry and hatch plots. As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss put it, ancient writing's main function was “to facilitate the enslavement of other human beings.” Personal uses of writing by nonprofessionals came only much later, as writing systems grew simpler and more expressive.

对于今天的我们来说,我们不禁要问:既然早期的书写系统是那样的不明确,使得文字的功能大受限制,只能为少数抄写员所掌握,那么拥有这些文字的社会为什么竟会容忍这种情况?但提出这个问题正好说明了在普及文字方面古人的观点和我们自己的期望之间的差距。早期文字在使用方面所受到的限制乃是蓄意造成的,这种情况对发明不那么含糊的书写系统产生了实实在在的抑制作用。古代苏美尔的国王和祭司们希望文字由专职的抄写员用来记录应完税缴纳的羊的头数,而不是由平民大众用来写诗和图谋不轨的。正如人类学家克劳德·莱维-斯特劳斯所说的那样,古代文字的主要功能是“方便对别人的奴役”。非专职人员个人使用文字只是很久以后的事,因为那时书写系统变得比较简单同时也更富于表现力。

For instance, with the fall of Mycenaean Greek civilization, around 1200 B.C., Linear B disappeared, and Greece returned to an age of preliteracy. When writing finally returned to Greece, in the eighth century B.C., the new Greek writing, its users, and its uses were very different. The writing was no longer an ambiguous syllabary mixed with logograms but an alphabet borrowed from the Phoenician consonantal alphabet and improved by the Greek invention of vowels. In place of lists of sheep, legible only to scribes and read only in palaces, Greek alphabetic writing from the moment of its appearance was a vehicle of poetry and humor, to be read in private homes. For instance, the first preserved example of Greek alphabetic writing, scratched onto an Athenian wine jug of about 740 B.C., is a line of poetry announcing a dancing contest: “Whoever of all dancers performs most nimbly will win this vase as a prize.” The next example is three lines of dactylic hexameter scratched onto a drinking cup: “I am Nestor's delicious drinking cup. Whoever drinks from this cup swiftly will the desire of fair-crowned Aphrodite seize him.” The earliest preserved examples of the Etruscan and Roman alphabets are also inscriptions on drinking cups and wine containers. Only later did the alphabet's easily learned vehicle of private communication become co-opted for public or bureaucratic purposes. Thus, the developmental sequence of uses for alphabetic writing was the reverse of that for the earlier systems of logograms and syllabaries.

例如,随着公元前1200年左右迈锡尼时代希腊文明的衰落,B类线形文字不见了,希腊重新回到了没有文字的时代。当文字在公元前8世纪终于又回到希腊时,这种新的希腊文字、它的使用者和它的用途已十分不同。这种文字不再是一种夹杂语标的含义不明的音节文字,而是一种借用腓尼基人的辅音字母再加上希腊人自己发明的元音而得到改进的字母文字。希腊的字母文字代替了那些只有抄写员看得懂、只在宫中阅读的记录绵羊头数的账目,从问世那一刻起就成了可以在私人家中阅读的诗歌和幽默的传播媒介。例如,希腊字母文字最早保存下来的例子,是刻在大约公元前740年的一只雅典酒罐上的一行宣布跳舞比赛的诗句:“舞姿最曼妙者将奖以此瓶。”第二个例子是刻在一只酒杯上的三行扬抑抑格6步韵诗句:“我是内斯特[13]的酒杯,盛满了玉液琼浆。谁只要飞快的喝上一口,头戴花冠的阿佛洛狄特[14]会使他的爱欲在心中激荡。”现存最早的伊特鲁里亚和罗马字母的例子,也是酒杯和酒罈上的铭文。只是到了后来,字母的这种容易掌握的个人交际媒介,才被用于公共或官方目的。因此,字母文字使用的发展顺序,同较早的语标文字和音节文字使用的发展顺序正好颠倒过来。

THE LIMITED USES and users of early writing suggest why writing appeared so late in human evolution. All of the likely or possible independent inventions of writing (in Sumer, Mexico, China, and Egypt), and all of the early adaptations of those invented systems (for example, those in Crete, Iran, Turkey, the Indus Valley, and the Maya area), involved socially stratified societies with complex and centralized political institutions, whose necessary relation to food production we shall explore in a later chapter. Early writing served the needs of those political institutions (such as record keeping and royal propaganda), and the users were full-time bureaucrats nourished by stored food surpluses grown by food-producing peasants. Writing was never developed or even adopted by hunter-gatherer societies, because they lacked both the institutional uses of early writing and the social and agricultural mechanisms for generating the food surpluses required to feed scribes.

早期文字在使用和使用者方面的限制表明,为什么文字在人类进化中出现得如此之晚。所有可能的对文字的独立发明(在苏美尔、墨西哥、中国和埃及),和所有早期的对这些发明出来的书写系统(如克里特岛、伊朗、土耳其、印度河河谷和马雅地区的书写系统)的采用,都涉及社会等级分明、具有复杂而集中统一的政治机构的社会,这种社会与粮食生产的必然联系,我们将留在下一章探讨。早期的文字是为这些政治机构的需要服务的(如记录的保存和对王室的宣传),而使用文字的人是由生产粮食的农民所种植的多余粮食养活的专职官员。狩猎采集社会没有发明出文字,甚至也没有采用过任何文字,因为它们既没有需要使用早期文字的机构,也没有生产为养活文字专家所必需的剩余粮食的社会机制和农业机制。

Thus, food production and thousands of years of societal evolution following its adoption were as essential for the evolution of writing as for the evolution of microbes causing human epidemic diseases. Writing arose independently only in the Fertile Crescent, Mexico, and probably China precisely because those were the first areas where food production emerged in their respective hemispheres. Once writing had been invented by those few societies, it then spread, by trade and conquest and religion, to other societies with similar economies and political organizations.

因此,粮食生产和采用粮食后几千年的社会进化,对于文字的演进同对于引起人类流行疾病的病菌的演化是同样必不可少的。文字只在新月沃地、墨西哥、可能还有中国独立出现,完全是因为这几个地方是粮食生产在它们各自的半球范围内出现的最早地区。一旦文字在这几个社会发明出来,它接着就通过贸易、征服和宗教向具有同样经济结构和政治组织的社会传播。

While food production was thus a necessary condition for the evolution or early adoption of writing, it was not a sufficient condition. At the beginning of this chapter, I mentioned the failure of some food-producing societies with complex political organization to develop or adopt writing before modern times. Those cases, initially so puzzling to us moderns accustomed to viewing writing as indispensable to a complex society, included one of the world's largest empires as of A.D. 1520, the Inca Empire of South America. They also included Tonga's maritime proto-empire, the Hawaiian state emerging in the late 18th century, all of the states and chiefdoms of subequatorial Africa and sub-Saharan West Africa before the arrival of Islam, and the largest native North American societies, those of the Mississippi Valley and its tributaries. Why did all those societies fail to acquire writing, despite their sharing prerequisites with societies that did do so?

虽然粮食生产就是这样地成为文字演变或早期文字采用的必要条件,但还不是充分的条件。在本章开始时,我曾提到,有些粮食生产的社会虽然已有复杂的政治组织,但在现代之前并未能发明或借用文字。我们现代人习惯于把文字看作是一个复杂社会必不可少的东西,所以这些例子一开始就使我们感到迷惑不解,这些例子还包括到公元1520年止的世界上最大的帝国之一——南美的印加帝国。这些例子还包括汤加的海洋原始帝国、18世纪晚些时候出现的夏威夷王国、赤道非洲和撒哈拉沙漠以南西非地区在伊斯兰教来到前的各个国家和酋长管辖地,以及密西西比河及其支流一带北美最大的印第安人社会。尽管所有这些社会也具有有文字社会的那些必备条件,但为什么它们却未能获得文字呢?

Here we have to remind ourselves that the vast majority of societies with writing acquired it by borrowing it from neighbors or by being inspired by them to develop it, rather than by independently inventing it themselves. The societies without writing that I just mentioned are ones that got a later start on food production than did Sumer, Mexico, and China. (The only uncertainty in this statement concerns the relative dates for the onset of food production in Mexico and in the Andes, the eventual Inca realm.) Given enough time, the societies lacking writing might also have eventually developed it on their own. Had they been located nearer to Sumer, Mexico, and China, they might instead have acquired writing or the idea of writing from those centers, just as did India, the Maya, and most other societies with writing. But they were too far from the first centers of writing to have acquired it before modern times.

这里,我们必须提醒一下自己,大多数有文字的社会之所以获得文字,或是通过向邻近的社会借用,或是由于受到它们的启发而发明出文字,而不是靠自己独立创造出来的。我刚才提到的那些没有文字的社会在粮食生产方面比苏美尔、墨西哥和中国起步晚。(这种说法唯一难以确定的是印加帝国的最后领地墨西哥和安第斯山脉地区粮食生产开始的有关年代问题。)如果假以时日,这些没有文字的社会也可能最后靠自己的力量发明出文字来。如果它们离苏美尔、墨西哥和中国更近一些,它们也会从这些中心得到文字或关于文字的思想,就像印度、马雅和其他大多数有文字的社会一样。但它们距离那些最早的文字中心太远了,所以没有能在现代之前获得文字。

The importance of isolation is most obvious for Hawaii and Tonga, both of which were separated by at least 4,000 miles of ocean from the nearest societies with writing. The other societies illustrate the important point that distance as the crow flies is not an appropriate measure of isolation for humans. The Andes, West Africa's kingdoms, and the mouth of the Mississippi River lay only about 1,200, 1,500, and 700 miles, respectively, from societies with writing in Mexico, North Africa, and Mexico, respectively. These distances are considerably less than the distances the alphabet had to travel from its homeland on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to reach Ireland, Ethiopia, and Southeast Asia within 2,000 years of its invention. But humans are slowed by ecological and water barriers that crows can fly over. The states of North Africa (with writing) and West Africa (without writing) were separated from each other by Saharan desert unsuitable for agriculture and cities. The deserts of northern Mexico similarly separated the urban centers of southern Mexico from the chiefdoms of the Mississippi Valley. Communication between southern Mexico and the Andes required either a sea voyage or else a long chain of overland contacts via the narrow, forested, never urbanized Isthmus of Darien. Hence the Andes, West Africa, and the Mississippi Valley were effectively rather isolated from societies with writing.

这种孤立状态的重要作用对夏威夷和汤加是极其明显的,这两个地方同最近的有文字的社会隔着重洋,相距至少有4000英里之遥。另一些社会则证明了这样一个重要的观点:乌鸦飞过的距离不是人类衡量孤立状态的一种恰当的尺度。安第斯山脉、西非的一些王国和密西西比河口与墨西哥、北非和墨西哥的有文字社会的距离,分别只有大约1200英里、1500英里和700英里。这些距离大大小于字母在其发明后的2000年中从发源地沿地中海东岸到达爱尔兰、埃塞俄比亚和东南亚所传播的距离。但人类前进的脚步却由于乌鸦能够飞越的生态障碍和水域阻隔而慢了下来。北非国家(有文字)和西非国家(没有文字)中间隔着不适于农业和城市的撒哈拉沙漠。墨西哥北部的沙漠同样把墨西哥南部的城市中心和密西西比河河谷的酋长管辖地分隔开来。墨西哥南部与安第斯山脉地区的交通需要靠海上航行,或经由狭窄的、森林覆盖的、从未城市化的达里安地峡的一连串陆路联系。因此,安第斯山脉地区、西非和密西西比河河谷实际上就同有文字的社会隔离了开来。

That's not to say that those societies without writing were totally isolated. West Africa eventually did receive Fertile Crescent domestic animals across the Sahara, and later accepted Islamic influence, including Arabic writing. Corn diffused from Mexico to the Andes and, more slowly, from Mexico to the Mississippi Valley. But we already saw in Chapter 10 that the north-south axes and ecological barriers within Africa and the Americas retarded the diffusion of crops and domestic animals. The history of writing illustrates strikingly the similar ways in which geography and ecology influenced the spread of human inventions.

这并不是说,那些没有文字的社会就是完全与世隔绝的。西非最后接受了撒哈拉沙漠另一边的新月沃地的家畜,后来又接受了伊斯兰教的影响,包括阿拉伯文字。玉米从墨西哥传播到安第斯山脉地区,又比较缓慢地从墨西哥传播到密西西比河河谷。但我们在第十章已经看到,非洲和美洲内的南北轴线和生态障碍阻滞了作物和家畜的传播。文字史引人注目地表明了类似的情况:地理和生态条件影响了人类发明的传播。

注释:

1 弥诺斯语:即古克里特语,古希腊克里特岛居民所使用的语言。——译者

2 迈锡尼时代约在公元前1500—1100年。——译者

3 闪语:指闪语族中的任何一种语言。闪语族属闪含语系,包括古希伯来语、阿拉伯语、阿拉米语、腓尼基语、亚述语、埃塞俄比亚语等。——译者

4 如尼文:北欧等地的一种古文字。——译者

5 欧甘字母:公元4世纪时用以在石碑上刻写爱尔兰语和皮克特语的欧甘文字母。——译者

6 阿拉姆语:属闪语族,公元前9世纪通用于古叙利亚、后来一度成为亚洲西南部的通用语,犹太人文献及早期基督教文学多以此语写成。——译者

7 伊特鲁斯坎人:意大利埃特鲁西亚地区古代民族。——译者

8 金素月(1305—1395):朝鲜诗人,原名廷湜。有乡土诗人和爱国抒情诗人之称。著有诗集《金达莱花》、《素月诗抄》等。——译者

9 吴历(1632—1718):江苏常熟人,清初画家,兼善书法,亦工诗。著有《墨井诗钞》、《三巴集》等。——译者

10 克诺索斯:克里特岛弥诺斯王的首都。1900年开始发掘,发现原来的宫殿及周围城市,公元前2000年左右,为繁荣的弥诺斯文化中心。——译者

11 派洛斯:希腊伯罗奔尼撒半岛西南美塞尼亚湾的古代港口。——译者

12 《伊利亚特》和《奥德赛》:古希腊史诗,相传均为荷马所作。前者主要叙述特洛伊战争最后一年的故事;后者描写奥德修斯于特洛伊城攻陷后回家10年流浪的种种经历。——译者

13 内斯特:希腊派洛斯的国王,希腊的贤明长者,曾参加对特洛伊城的围攻。——译者

14 阿佛洛狄特:希腊神话中爱与美的女神,相当于罗马神话中的维纳斯。——译者