CHAPTER 13

第十三章

NECESSITY'S MOTHER

需要之母

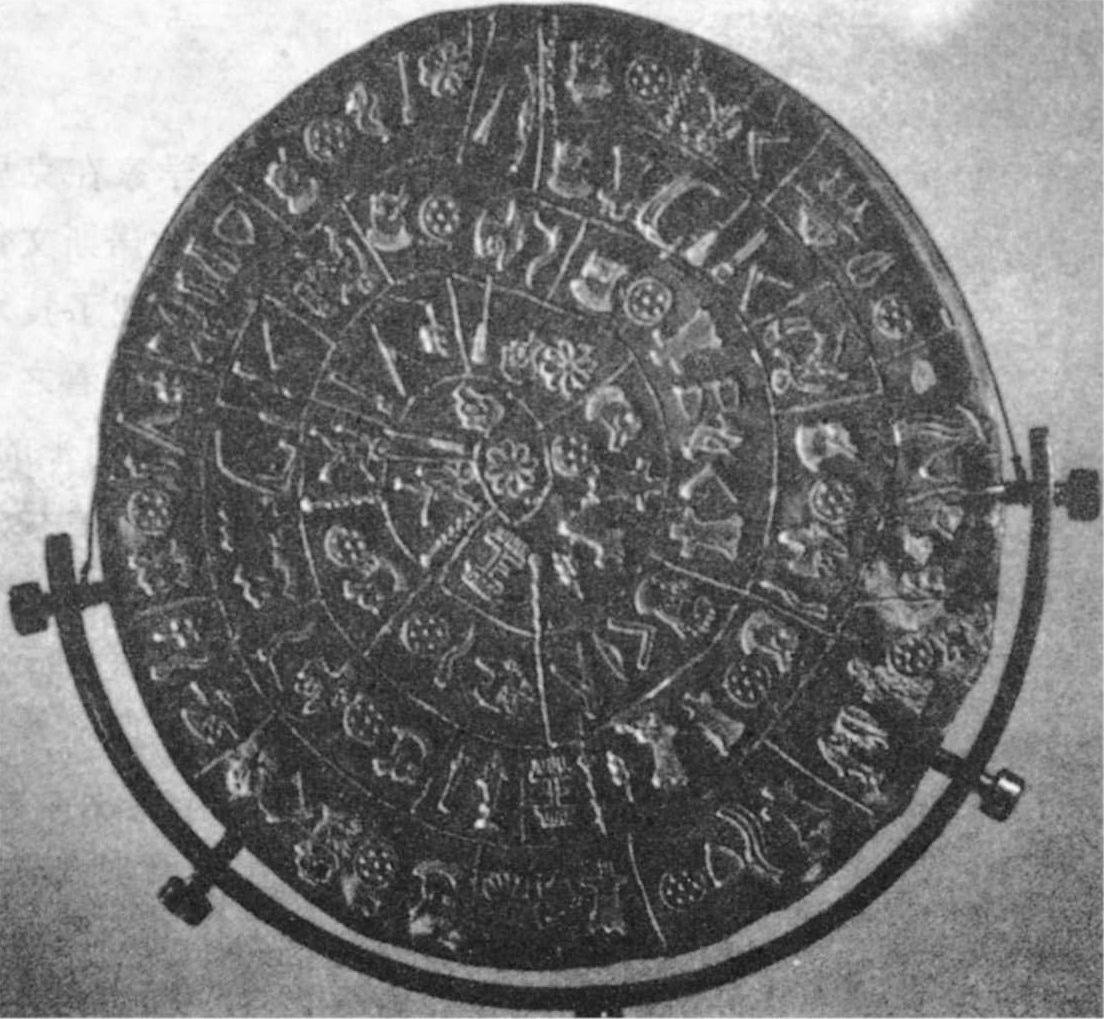

ON JULY 3, 1908, ARCHAEOLOGISTS EXCAVATING THE ancient Minoan palace at Phaistos, on the island of Crete, chanced upon one of the most remarkable objects in the history of technology. At first glance it seemed unprepossessing: just a small, flat, unpainted, circular disk of hard-baked clay, 6 inches in diameter. Closer examination showed each side to be covered with writing, resting on a curved line that spiraled clockwise in five coils from the disk's rim to its center. A total of 241 signs or letters was neatly divided by etched vertical lines into groups of several signs, possibly constituting words. The writer must have planned and executed the disk with care, so as to start writing at the rim and fill up all the available space along the spiraling line, yet not run out of space on reaching the center.

1908年7月3日,一些考古学家在克里特岛上对菲斯托斯的古代弥诺斯文化时期的宫殿进行发掘,无意中发现了技术史上最引人注目的物品之一。它乍看之下似乎貌不惊人,只是一个小小的、扁平的、没有彩绘的圆盘,由黏土烘制而成,直径为6.5英寸。再仔细观察一下,就发现这个圆盘的每一面都布满了文字,文字落在一条曲线上,而曲线则以顺时钟方向从圆盘边缘呈螺旋形通向圆盘中央,一共有5圈。总共241个字母符号由刻出来的垂直线整齐地分成若干组,每组包含几个不同的符号,可能就是这些符号构成了词。作者必定仔细地设计和制作了这个圆盘,这样就可以从圆盘的边缘写起,沿螺旋线写满全部可以利用的空间,然而在到达圆盘中央时空间正好够用(见下图)。

Ever since it was unearthed, the disk has posed a mystery for historians of writing. The number of distinct signs (45) suggests a syllabary rather than an alphabet, but it is still undeciphered, and the forms of the signs are unlike those of any other known writing system. Not another scrap of the strange script has turned up in the 89 years since its discovery. Thus, it remains unknown whether it represents an indigenous Cretan script or a foreign import to Crete.

自出土以来,这个圆盘一直成为文字史家的一个不解之谜。不同符号的数目(45个)表明这是一种音节文字,而不是字母文字,但它仍没有得到解释,而且符号的形式也不同于其他任何已知的书写系统的符号形式。在它发现后的89年中,这种奇怪文字连零星碎片也没有再出现过。因此,它究竟是代表了克里特岛的一种本地文字,还是从外地进入克里特岛的舶来品,这仍然不得而知。

One side of the two-sided Phaistos Disk.

菲斯托斯双面圆盘的一面

For historians of technology, the Phaistos disk is even more baffling; its estimated date of 1700 B.C. makes it by far the earliest printed document in the world. Instead of being etched by hand, as were all texts of Crete's later Linear A and Linear B scripts, the disk's signs were punched into soft clay (subsequently baked hard) by stamps that bore a sign as raised type. The printer evidently had a set of at least 45 stamps, one for each sign appearing on the disk. Making these stamps must have entailed a great deal of work, and they surely weren't manufactured just to print this single document. Whoever used them was presumably doing a lot of writing. With those stamps, their owner could make copies much more quickly and neatly than if he or she had written out each of the script's complicated signs at each appearance.

对技术史家来说,这个菲斯托斯圆盘甚至更加令人困惑;它的年代估计为公元前1700年,这使它成为世界上最早的印刷文件。圆盘上的符号不像克里特岛后来的A类线形文字和B类线形文字所有的文本那样是用手刻写的,而是用带有凸起铅字似的符号的印章在柔软的黏土上压印出来的(黏土随后被烘干硬化)。这位印工显然有一套至少45个印章,一个印章印出圆盘上的一个符号。制作这些印章必然要花费大量的劳动,而它们肯定不是仅仅为了印这一个文件而被制造出来的。使用这些印章的人大概有许多东西要写。有了这些印章,印章的主人就可以迅速得多、整齐得多地去进行复制,这是他或她在每一个地方写出每一个文字的复杂符号所无法比拟的。

The Phaistos disk anticipates humanity's next efforts at printing, which similarly used cut type or blocks but applied them to paper with ink, not to clay without ink. However, those next efforts did not appear until 2,500 years later in China and 3,100 years later in medieval Europe. Why was the disk's precocious technology not widely adopted in Crete or elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean? Why was its printing method invented around 1700 B.C. in Crete and not at some other time in Mesopotamia, Mexico, or any other ancient center of writing? Why did it then take thousands of years to add the ideas of ink and a press and arrive at a printing press? The disk thus constitutes a threatening challenge to historians. If inventions are as idiosyncratic and unpredictable as the disk seems to suggest, then efforts to generalize about the history of technology may be doomed from the outset.

菲斯托斯圆盘开人类下一步印刷业之先河。因为印刷也同样使用字模或印板,但却是直接沾墨水印在纸上,而不是不沾墨水印在黏土上。然而,这些接下去的尝试直到2500年后才在中国出现,在3100年后在中世纪的欧洲出现。圆盘的这种早熟的技术,为什么没有在古代地中海的克里特岛或其他地方得到广泛的采用?为什么它的印刷方法是在公元前1700年左右在克里特岛发明出来,而不是在其他某个时间在美索不达米亚、墨西哥或其他任何一个古代文字中心发明出来?为什么接着又花了几千年时间才又加上用墨水和压印机这个主意从而得到了印刷机?这个圆盘就是这样地成了对历史学家的咄咄逼人的挑战。如果发明创造都像这个圆盘似乎表明的那样独特而难以捉摸,那么想要对技术史进行综合的努力可能一开始就注定要失败的。

Technology, in the form of weapons and transport, provides the direct means by which certain peoples have expanded their realms and conquered other peoples. That makes it the leading cause of history's broadest pattern. But why were Eurasians, rather than Native Americans or sub-Saharan Africans, the ones to invent firearms, oceangoing ships, and steel equipment? The differences extend to most other significant technological advances, from printing presses to glass and steam engines. Why were all those inventions Eurasian? Why were all New Guineans and Native Australians in A.D. 1800 still using stone tools like ones discarded thousands of years ago in Eurasia and most of Africa, even though some of the world's richest copper and iron deposits are in New Guinea and Australia, respectively? All those facts explain why so many laypeople assume that Eurasians are superior to other peoples in inventiveness and intelligence.

表现为武器和运输工具的技术,提供了某些民族用来扩张自己领域和征服其他民族的直接手段。这就使技术成了历史最广泛模式的主要成因。但是,为什么是欧亚大陆人而不是印第安人或撒哈拉沙漠以南的非洲人发明了火器、远洋船只和钢铁设备?这种差异扩大到了从印刷机到玻璃和蒸汽机的其他大多数技术进步。为什么所有这些发明创造都是欧亚大陆人的?虽然世界上一些蕴藏最丰富的铜矿和铁矿分别在新几内亚和澳大利亚,但为什么所有新几内亚人和澳大利亚土著在公元1800年还在使用几千年前就已在欧亚大陆、非洲大部分地区被抛弃了的那种石器?所有这些事实说明,为什么有那么多的外行人想当然地认为,欧亚大陆人在创造性和智力方面要比其他民族高出一筹。

If, on the other hand, no such difference in human neurobiology exists to account for continental differences in technological development, what does account for them? An alternative view rests on the heroic theory of invention. Technological advances seem to come disproportionately from a few very rare geniuses, such as Johannes Gutenberg, James Watt, Thomas Edison, and the Wright brothers. They were Europeans, or descendants of European emigrants to America. So were Archimedes and other rare geniuses of ancient times. Could such geniuses have equally well been born in Tasmania or Namibia? Does the history of technology depend on nothing more than accidents of the birthplaces of a few inventors?

另一方面,如果在人类神经生物学方面没有任何此种差异可以说明各大陆在技术发展方面的差异,那么用什么来说明呢?另外一种观点是以发明创造的英雄理论为基础的。技术进步似乎特别多地依靠少数十分稀有的天才如约翰内斯·谷登堡[1]、詹姆士·瓦特、托马斯·爱迪生和莱特兄弟。他们或是欧洲人,或是移居美国的欧洲人的后代。阿基米德和古代的其他一些稀有天才也是欧洲人。这样的天才会不会也生在塔斯马尼亚岛[2]或纳米比亚呢?难道技术史仅仅决定于几个发明家的出生地这些偶然因素吗?

Still another alternative view holds that it is a matter not of individual inventiveness but of the receptivity of whole societies to innovation. Some societies seem hopelessly conservative, inward looking, and hostile to change. That's the impression of many Westerners who have attempted to help Third World peoples and ended up discouraged. The people seem perfectly intelligent as individuals; the problem seems instead to lie with their societies. How else can one explain why the Aborigines of northeastern Australia failed to adopt bows and arrows, which they saw being used by Torres Straits islanders with whom they traded? Might all the societies of an entire continent be unreceptive, thereby explaining technology's slow pace of development there? In this chapter we shall finally come to grips with a central problem of this book: the question of why technology did evolve at such different rates on different continents.

还有一种观点认为,这不是个人的创造性问题,而是整个社会对新事物的接受性问题。有些社会无可救药地保守、内向、敌视变革。许多西方人都会有这种印象,他们本来想要帮助第三世界人民,最后却落得灰心丧气。第三世界的人作为个人似乎绝对聪明;问题似乎在他们的社会。否则又怎样来解释澳大利亚东北部的土著为什么没有采用弓箭?而他们见过与他们进行贸易的托雷斯海峡的岛上居民在使用弓箭。也许整个大陆的所有社会都不接受新事物,并由此说明那里的技术发展速度缓慢?在本章中,我们最终将要涉及本书的一个中心问题:为什么在不同的大陆上技术以不同的速度演进的问题。

THE STARTING POINT for our discussion is the common view expressed in the saying “Necessity is the mother of invention.” That is, inventions supposedly arise when a society has an unfulfilled need: some technology is widely recognized to be unsatisfactory or limiting. Would-be inventors, motivated by the prospect of money or fame, perceive the need and try to meet it. Some inventor finally comes up with a solution superior to the existing, unsatisfactory technology. Society adopts the solution if it is compatible with the society's values and other technologies.

我们讨论的起始点是“需要乃发明之母”这个格言所表达的普遍观点。就是说,发明的出现可能是由于社会有一种未得到满足的需要:人们普遍承认,某种技术是不能令人满意的,或是作用有限的。想要做发明家的人为金钱和名誉的前景所驱使,察觉到了这种需要,并努力去予以满足。某个发明家最后想出了一个比现有的不能令人满意的技术高明的解决办法。如果这个解决办法符合社会的价值观,与其他技术也能协调,社会就会予以采纳。

Quite a few inventions do conform to this commonsense view of necessity as invention's mother. In 1942, in the middle of World War II, the U.S. government set up the Manhattan Project with the explicit goal of inventing the technology required to build an atomic bomb before Nazi Germany could do so. That project succeeded in three years, at a cost of $2 billion (equivalent to over $20 billion today). Other instances are Eli Whitney's 1794 invention of his cotton gin to replace laborious hand cleaning of cotton grown in the U.S. South, and James Watt's 1769 invention of his steam engine to solve the problem of pumping water out of British coal mines.

相当多的发明都符合需要乃发明之母这个常识性的观点。1942年,当第二次世界大战仍在进行时,美国政府制定了曼哈顿计划,其显而易见的目的就是抢在纳粹之前发明出为制造原子弹所需要的技术。3年后,这个计划成功了,共花去20亿美元(相当于今天的200多亿美元)。其他的例子有,1794年伊莱·惠特尼发明了轧棉机,来代替把美国南部种植的棉花的棉绒剥离下来的繁重的手工劳动,还有1769年詹姆士·瓦特发明了蒸汽机来解决从英国煤矿里抽水的问题。

These familiar examples deceive us into assuming that other major inventions were also responses to perceived needs. In fact, many or most inventions were developed by people driven by curiosity or by a love of tinkering, in the absence of any initial demand for the product they had in mind. Once a device had been invented, the inventor then had to find an application for it. Only after it had been in use for a considerable time did consumers come to feel that they “needed” it. Still other devices, invented to serve one purpose, eventually found most of their use for other, unanticipated purposes. It may come as a surprise to learn that these inventions in search of a use include most of the major technological breakthroughs of modern times, ranging from the airplane and automobile, through the internal combustion engine and electric light bulb, to the phonograph and transistor. Thus, invention is often the mother of necessity, rather than vice versa.

这些人们耳熟能详的例子,使我们误以为其他的重大发明也是为了满足觉察到的需要。事实上,许多发明或大多数发明都是一些被好奇心驱使的人或喜欢动手修修补补的人搞出来的,当初并不存在对他们所想到的产品的任何需要。一旦发明了一种装置,发明者就得为它找到应用的地方。只有在它被使用了相当一段时间以后,消费者才会感到他们“需要”它。还有一些装置本来是只为一个目的而发明出来的,最后却为其他一些意料之外的目的找到了它们的大多数用途。寻求使用的这些发明包括现代大多数重大的技术突破,从飞机和汽车到内燃机和电灯泡再到留声机和晶体管,应有尽有。了解到这一点,也许会令人感到吃惊。因此,发明常常是需要之母,而不是相反。

A good example is the history of Thomas Edison's phonograph, the most original invention of the greatest inventor of modern times. When Edison built his first phonograph in 1877, he published an article proposing ten uses to which his invention might be put. They included preserving the last words of dying people, recording books for blind people to hear, announcing clock time, and teaching spelling. Reproduction of music was not high on Edison's list of priorities. A few years later Edison told his assistant that his invention had no commercial value. Within another few years he changed his mind and did enter business to sell phonographs—but for use as office dictating machines. When other entrepreneurs created jukeboxes by arranging for a phonograph to play popular music at the drop of a coin, Edison objected to this debasement, which apparently detracted from serious office use of his invention. Only after about 20 years did Edison reluctantly concede that the main use of his phonograph was to record and play music.

一个很好的例子就是托马斯·爱迪生的留声机的发明史。留声机是现代最伟大的发明家的最具独创性的发明。爱迪生于1877年创造出了他的第一架留声机时,发表了一篇文章,提出他的发明可以有10种用途。它们包括保存垂死的人的遗言,录下书的内容让盲人来听,为时钟报时以及教授拼写。音乐复制在他列举的用途中并不占有很高的优先地位。几年后,爱迪生对他的助手说,他的发明没有任何商业价值。又过了不到几年,他改变了主意,做起销售留声机的生意来——但作为办公室口述记录机使用。当其他一些企业家把留声改装成播放流行音乐的投币自动唱机时,爱迪生反对这种糟蹋他的发明的做法,因为那显然贬低了他的发明在办公室里的正经用途。只是在过了大约20年之后,爱迪生才勉勉强强地承认他的留声机的主要用途是录放音乐。

The motor vehicle is another invention whose uses seem obvious today. However, it was not invented in response to any demand. When Nikolaus Otto built his first gas engine, in 1866, horses had been supplying people's land transportation needs for nearly 6,000 years, supplemented increasingly by steam-powered railroads for several decades. There was no crisis in the availability of horses, no dissatisfaction with railroads.

机动车是另一个在今天看来用途似乎显而易见的发明。然而,它不是为满足任何需求而发明出来的。当尼古劳斯·奥托于1866年造出了他的第一台4冲程气化器式发动机时,马在满足人们陆上运输需要方面已经有了将近6000年的历史,在最近的几十年里又日益得到蒸汽动力铁路的补充。在获得马匹方面不存在任何危机,人们对于铁路也没有任何不满。

Because Otto's engine was weak, heavy, and seven feet tall, it did not recommend itself over horses. Not until 1885 did engines improve to the point that Gottfried Daimler got around to installing one on a bicycle to create the first motorcycle; he waited until 1896 to build the first truck.

由于奥托的发动机力量小、笨重和高达7英尺,所以它并不比马匹更为可取。直到1885年,发动机的改进使戈特利布·戴姆勒得以在一辆自行车上安装了一台发动机从而制造了第一辆摩托车;他一直等到1896年才制造了第一辆卡车。

In 1905, motor vehicles were still expensive, unreliable toys for the rich. Public contentment with horses and railroads remained high until World War I, when the military concluded that it really did need trucks. Intensive postwar lobbying by truck manufacturers and armies finally convinced the public of its own needs and enabled trucks to begin to supplant horse-drawn wagons in industrialized countries. Even in the largest American cities, the changeover took 50 years.

1905年,机动车仍是有钱人的昂贵而不可靠的玩物。公众对马匹和铁路的满意程度始终很高,直到第一次世界大战时军方认定它的确需要卡车。战后卡车制造商和军队进行了大量游说,使公众相信他们对机动车辆的需要,从而使卡车得以在工业化国家开始取代马车。甚至在美国的最大城市里,这种改变也花了50年时间。

Inventors often have to persist at their tinkering for a long time in the absence of public demand, because early models perform too poorly to be useful. The first cameras, typewriters, and television sets were as awful as Otto's seven-foot-tall gas engine. That makes it difficult for an inventor to foresee whether his or her awful prototype might eventually find a use and thus warrant more time and expense to develop it. Each year, the United States issues about 70,000 patents, only a few of which ultimately reach the stage of commercial production. For each great invention that ultimately found a use, there are countless others that did not. Even inventions that meet the need for which they were initially designed may later prove more valuable at meeting unforeseen needs. While James Watt designed his steam engine to pump water from mines, it soon was supplying power to cotton mills, then (with much greater profit) propelling locomotives and boats.

发明家们常常不得不在没有公众需求的情况下长期坚持他们的修修补补的工作,因为他们的早期样机性能太差,派不了用场。最早的照相机、打字机和电视机同奥托的7英尺高的内燃发动机一样使人不敢领教。这就使发明者难以预知他们发明的可怕的原型最终是否可以得到使用,从而是否应该投入更多的时间和费用来对它进行开发。美国每年要颁发大约7万份专利证书,但只有少数专利最后达到商业性生产阶段。有一项大发明最终得到使用,就会有不计其数的其他发明得不到使用。甚至有些发明当初本来是为了满足特定的需要而设计的,后来可能在满足意外需要方面证明是更有价值的。虽然詹姆士·瓦特设计他的蒸汽机是为了从煤矿里抽水,但它很快就为棉纺厂提供动力,接着又(以大得多的利润)推动着机车和轮船前进。

THUS, THE COMMONSENSE view of invention that served as our starting point reverses the usual roles of invention and need. It also overstates the importance of rare geniuses, such as Watt and Edison. That “heroic theory of invention,” as it is termed, is encouraged by patent law, because an applicant for a patent must prove the novelty of the invention submitted. Inventors thereby have a financial incentive to denigrate or ignore previous work. From a patent lawyer's perspective, the ideal invention is one that arises without any precursors, like Athene springing fully formed from the forehead of Zeus.

因此,被用作我们讨论的起始点的关于发明的常识性观点,把发明的通常作用和需要弄颠倒了。它也夸大了诸如瓦特和爱迪生之类稀有天才的重要性。所谓“发明的英雄理论”之所以得到专利法的鼓励,是因为申请一项专利必须证明所提交的发明具有新意。发明者出于财政的动机而贬低或忽视前人的成果。从专利法律师观点看,最佳的发明就是全无先例的发明,就像雅典娜整个地从宙斯的前额跳出来一样[3]。

In reality, even for the most famous and apparently decisive modern inventions, neglected precursors lurked behind the bald claim “X invented Y.” For instance, we are regularly told, “James Watt invented the steam engine in 1769,” supposedly inspired by watching steam rise from a teakettle's spout. Unfortunately for this splendid fiction, Watt actually got the idea for his particular steam engine while repairing a model of Thomas Newcomen's steam engine, which Newcomen had invented 57 years earlier and of which over a hundred had been manufactured in England by the time of Watt's repair work. Newcomen's engine, in turn, followed the steam engine that the Englishman Thomas Savery patented in 1698, which followed the steam engine that the Frenchman Denis Papin designed (but did not build) around 1680, which in turn had precursors in the ideas of the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens and others. All this is not to deny that Watt greatly improved Newcomen's engine (by incorporating a separate steam condenser and a double-acting cylinder), just as Newcomen had greatly improved Savery's.

实际上,即使对那些最著名的而且显然具有决定意义的现代发明来说,就是“某人发明某物”这种不加掩饰的说法背后有着被忽视了的先例的影子。例如,我们经常听到人们说,“詹姆斯·瓦特于1769年发明了蒸汽机”,据说他是由于看到蒸汽从水壶嘴冒出来而受到了启发。这个故事实在太妙了,但可惜的是,瓦特打算制造自己的蒸汽机的想法,实际上是在他修理托马斯·纽科曼的一台原型蒸汽机时产生的。这种蒸汽机纽科曼在57年前就已发明出来了,到瓦特修理时,英格兰已经制造出100多台。而纽科曼的蒸汽机又是在英国人托马斯·萨弗里于1698年获得专利权之后才有的,但在萨弗里获得专利权之前,法国人丹尼·帕庞已于1680年左右设计出这种蒸汽机(但没有制造),而帕庞的设计思想则来自他的前人荷兰科学家克里斯蒂安·惠更斯和其他人。所有这些并不是要否认瓦特大大改进了纽科曼的蒸汽机(把一个独立的蒸汽冷凝器同一个往复式汽缸合并在一起),就像纽科曼曾经大大改进了萨弗里的蒸汽机一样。

Similar histories can be related for all modern inventions that are adequately documented. The hero customarily credited with the invention followed previous inventors who had had similar aims and had already produced designs, working models, or (as in the case of the Newcomen steam engine) commercially successful models. Edison's famous “invention” of the incandescent light bulb on the night of October 21, 1879, improved on many other incandescent light bulbs patented by other inventors between 1841 and 1878. Similarly, the Wright brothers' manned powered airplane was preceded by the manned unpowered gliders of Otto Lilienthal and the unmanned powered airplane of Samuel Langley; Samuel Morse's telegraph was preceded by those of Joseph Henry, William Cooke, and Charles Wheatstone; and Eli Whitney's gin for cleaning short-staple (inland) cotton extended gins that had been cleaning long-staple (Sea Island) cotton for thousands of years.

对所有有足够文件证明的现代发明都可以讲出类似的发展史。习惯上认为有发明才能的英雄仿效以前的一些发明者,而这些发明者也具有同样的目标,并已作出了一些设计、造出了一些工作样机或(就像纽科曼的蒸汽机一样)可以成功地投入商业使用的样机。爱迪生的1879年10月21日夜间著名的白炽灯泡的“发明”,只是对从1841年到1878年的其他发明者获得专利权的其他许多白炽灯泡的改进。同样,在莱特兄弟的载人飞机之前已有了奥托·利林塔尔的载人无动力滑翔机和塞缪尔·兰利的不载人动力飞机;在塞缪尔·莫尔斯的电报机之前已有了约瑟夫·亨利、威廉·库克和查尔斯·惠斯通的电报机了;而伊莱·惠特尼的短绒(内陆)棉轧棉机不过是几千年来长绒(海岛)棉轧棉机的应用范围的扩大罢了。

All this is not to deny that Watt, Edison, the Wright brothers, Morse, and Whitney made big improvements and thereby increased or inaugurated commercial success. The form of the invention eventually adopted might have been somewhat different without the recognized inventor's contribution. But the question for our purposes is whether the broad pattern of world history would have been altered significantly if some genius inventor had not been born at a particular place and time. The answer is clear: there has never been any such person. All recognized famous inventors had capable predecessors and successors and made their improvements at a time when society was capable of using their product. As we shall see, the tragedy of the hero who perfected the stamps used for the Phaistos disk was that he or she devised something that the society of the time could not exploit on a large scale.

所有这些并不是要否认瓦特、爱迪生、莱特兄弟、莫尔斯和惠特尼作出了巨大的改进,因而增加了或开创了商业成功的机会。如果没有那位公认的发明者的贡献,发明物最后采用的形式可能已有所不同了。但我们所讨论的问题是:如果某些天才发明家不是在某个时候出生在某个地方,世界史的广泛模式会不会因此而产生重大的变化。答案很清楚:从来就没有这样的人。所有公认的著名发明家都有一些有本领的前人和后人,而且他们是在社会有可能使用他们的成果的时候对原来的发明作出改进的。我们将会看到,对用于菲斯托斯圆盘的印章作出改进的那位英雄的悲剧在于,他或她发明了当时社会不能予以大规模利用的东西。

MY EXAMPLES SO far have been drawn from modern technologies, because their histories are well known. My two main conclusions are that technology develops cumulatively, rather than in isolated heroic acts, and that it finds most of its uses after it has been invented, rather than being invented to meet a foreseen need. These conclusions surely apply with much greater force to the undocumented history of ancient technology. When Ice Age hunter-gatherers noticed burned sand and limestone residues in their hearths, it was impossible for them to foresee the long, serendipitous accumulation of discoveries that would lead to the first Roman glass windows (around A.D. 1), by way of the first objects with surface glazes (around 4000 B.C.), the first free-standing glass objects of Egypt and Mesopotamia (around 2500 B.C.), and the first glass vessels (around 1500 B.C.).

到目前为止,我所举的这些例子都来自现代技术,因为现代技术发展史是众所周知的。我的两个主要结论是:技术的发展是长期积累的,而不是靠孤立的英雄行为;技术在发明出来后大部分都得到了使用,而不是发明出来去满足某种预见到的需要。如果把这两个结论用于没有文件证明的古代技术发展史,那就更加有说服力得多。当冰期的狩猎采集族群注意到他们的炉膛里焚烧过的沙子和石灰岩的残留物时,他们不可能预见到这种长期的偶然积累起来的发现会导致最早的罗马的玻璃窗(公元元年左右),而这种积累过程则是从最早的表面有半透明薄涂层的物品(公元前4000年左右),到最早的埃及和美索不达米亚的独立的类似玻璃的物品(公元前2500年左右),再到最早的玻璃器皿(公元前1500年左右)。

We know nothing about how those earliest known surface glazes themselves were developed. Nevertheless, we can infer the methods of prehistoric invention by watching technologically “primitive” people today, such as the New Guineans with whom I work. I already mentioned their knowledge of hundreds of local plant and animal species and each species' edibility, medical value, and other uses. New Guineans told me similarly about dozens of rock types in their environment and each type's hardness, color, behavior when struck or flaked, and uses. All of that knowledge is acquired by observation and by trial and error. I see that process of “invention” going on whenever I take New Guineans to work with me in an area away from their homes. They constantly pick up unfamiliar things in the forest, tinker with them, and occasionally find them useful enough to bring home. I see the same process when I am abandoning a campsite, and local people come to scavenge what is left. They play with my discarded objects and try to figure out whether they might be useful in New Guinea society. Discarded tin cans are easy: they end up reused as containers. Other objects are tested for purposes very different from the one for which they were manufactured. How would that yellow number 2 pencil look as an ornament, inserted through a pierced ear-lobe or nasal septum? Is that piece of broken glass sufficiently sharp and strong to be useful as a knife? Eureka!

对于那些已知最早的表面半透明薄涂层本身是怎么搞出来的,我们则一无所知。不过,通过观察今天在技术上“原始的”族群,如我与之一起工作的那些新几内亚人,我们可以推知史前的发明方法。我已经提起过他们认识几百种当地的植物和动物,知道每一种是否可以食用、它的药用价值和其他用途。新几内亚人同样还把他们周围的几十种石头讲给我听,告诉我每一种的硬度、颜色、在遭到敲打或削凿时的情况以及各种用途。所有这方面的知识都是通过观察和反复试验而获得的。每当我带领新几内亚人到远离他们家乡的地方工作时,我都看到了这种“发明”过程在进行。他们不断地在森林里捡起一些不熟悉的东西,拿在手中摆弄,偶尔发现有用就带回家去。当我放弃了营地,当地人跑来在丢弃物中寻找有用的东西时,我看到了同样的过程。他们把玩我丢弃的东西,设法弄清楚它们在新几内亚社会里是否有用。丢弃的马口铁罐的用途是容易确定的:它们最后被当作容器重新使用。其他东西则经过试验,用于完全不同于当初制造时的目的。把那支黄色的2号铅笔插进穿孔的耳垂和鼻隔做装饰品,看上去会不会很漂亮?那块碎玻璃是否很锋利,很结实,可以当刀来使用?我发现了![4]

The raw substances available to ancient peoples were natural materials such as stone, wood, bone, skins, fiber, clay, sand, limestone, and minerals, all existing in great variety. From those materials, people gradually learned to work particular types of stone, wood, and bone into tools; to convert particular clays into pottery and bricks; to convert certain mixtures of sand, limestone, and other “dirt” into glass; and to work available pure soft metals such as copper and gold, then to extract metals from ores, and finally to work hard metals such as bronze and iron.

古人能够利用的原料都是自然材料,如石头、木头、骨头、兽皮、纤维、黏土、沙子、灰岩和矿物,各种各样,数量众多。人们根据这些材料逐步学会了把某些种类的石头、木头和骨头制成工具;把某些黏土制成陶器和砖;把沙子、灰岩和其他“污物”混合在一起制成玻璃;对现有的纯粹的软金属如铜和金进行加工,后来又从矿石里提炼金属,最后又对硬金属如青铜和铁进行加工。

A good illustration of the histories of trial and error involved is furnished by the development of gunpowder and gasoline from raw materials. Combustible natural products inevitably make themselves noticed, as when a resinous log explodes in a campfire. By 2000 B.C., Mesopotamians were extracting tons of petroleum by heating rock asphalt. Ancient Greeks discovered the uses of various mixtures of petroleum, pitch, resins, sulfur, and quicklime as incendiary weapons, delivered by catapults, arrows, firebombs, and ships. The expertise at distillation that medieval Islamic alchemists developed to produce alcohols and perfumes also let them distill petroleum into fractions, some of which proved to be even more powerful incendiaries. Delivered in grenades, rockets, and torpedoes, those incendiaries played a key role in Islam's eventual defeat of the Crusaders. By then, the Chinese had observed that a particular mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter, which became known as gunpowder, was especially explosive. An Islamic chemical treatise of about A.D. 1100 describes seven gunpowder recipes, while a treatise from A.D. 1280 gives more than 70 recipes that had proved suitable for diverse purposes (one for rockets, another for cannons).

有关反复试验的发展过程的一个很好的例子,是从原料产生火药和汽油。可以燃烧的自然产物必然会引起人们的注意,如富含树脂的圆木在营火中爆燃。到公元前2000年,美索不达米亚平原上的人通过加热天然沥青提炼出大量的石油。古希腊人发现,石油和沥青、树脂、硫磺、生石灰的各种混合物,可以用作由弩炮、弓箭、火焰炸弹和船只来发射的火攻武器。中世纪伊斯兰教的炼金术士为生产酒精和香水而发明的蒸馏技术,也使他们把石油蒸馏成馏分,其中有些证明是威力甚至更加强大的燃烧剂。用手榴弹、火箭和爆炸装置来发射的这些燃烧剂,在伊斯兰教最后打败十字军的战争中起了关键的作用。在这之前,中国人也已观察到硫磺、木炭和硝石的一种特殊混合物的爆炸力特别强,这种混合物就叫做火药。公元1100年左右,伊斯兰教的一篇化学论文介绍了火药的7种配方,而公元1280年的一篇论文则提到了70多种适用于不同目的的配方(一种适用于火箭,另一种适用于大炮)。

As for postmedieval petroleum distillation, 19th-century chemists found the middle distillate fraction useful as fuel for oil lamps. The chemists discarded the most volatile fraction (gasoline) as an unfortunate waste product—until it was found to be an ideal fuel for internal-combustion engines. Who today remembers that gasoline, the fuel of modern civilization, originated as yet another invention in search of a use?

至于中世纪以后的石油蒸馏,19世纪的化学家们发现中间馏分油可以用作油灯的燃料。这些化学家把最易挥发的馏分(汽油)当作一种没有用的废品而予以抛弃——直到后来发现那是内燃机的一种理想的燃料。今天还有谁记得汽油这种现代文明的燃料当初曾是又一个寻求使用的发明呢?

ONCE AN INVENTOR has discovered a use for a new technology, the next step is to persuade society to adopt it. Merely having a bigger, faster, more powerful device for doing something is no guarantee of ready acceptance. Innumerable such technologies were either not adopted at all or adopted only after prolonged resistance. Notorious examples include the U.S. Congress's rejection of funds to develop a supersonic transport in 1971, the world's continued rejection of an efficiently designed typewriter keyboard, and Britain's long reluctance to adopt electric lighting. What is it that promotes an invention's acceptance by a society?

一旦发明家发现了一项新技术的用途,下一步就是说服社会来采用它。仅仅有一种更大、更快、更有效的工作装置还不能保证人们会乐于接受。无数的此类技术要么根本没有被采用,要么只是在长期的抵制之后才被采用。这方面臭名昭著的例子有:1971年美国国会拒绝考虑为发展超音速运输提供资金;全世界继续拒绝一种高效打字机的键盘设计,以及英国长期不愿采用电灯照明。那么,究竟是什么促使社会去接受发明呢?

Let's begin by comparing the acceptability of different inventions within the same society. It turns out that at least four factors influence acceptance.

让我们首先比较一下在同一个社会内对不同发明的接受能力。结果,至少有4个因素影响着对发明的接受。

The first and most obvious factor is relative economic advantage compared with existing technology. While wheels are very useful in modern industrial societies, that has not been so in some other societies. Ancient Native Mexicans invented wheeled vehicles with axles for use as toys, but not for transport. That seems incredible to us, until we reflect that ancient Mexicans lacked domestic animals to hitch to their wheeled vehicles, which therefore offered no advantage over human porters.

第一个也是最明显的因素,是与现有技术相比较的相对经济利益。虽然轮子在现代工业社会里非常有用,但在其他一些社会里情况就并非如此。古代墨西哥土著发明了带车轴和车轮的车子,但那是当玩具用的,而不是用于运输。这在我们看来似乎不可思议,直到我们想起了古代墨西哥人没有可以套上他们的带轮子的车子的牲口,因此这种车子并不比搬运工有任何优势。

A second consideration is social value and prestige, which can override economic benefit (or lack thereof). Millions of people today buy designer jeans for double the price of equally durable generic jeans—because the social cachet of the designer label counts for more than the extra cost. Similarly, Japan continues to use its horrendously cumbersome kanji writing system in preference to efficient alphabets or Japan's own efficient kana syllabary—because the prestige attached to kanji is so great.

第二个考虑是社会价值和声望,这种考虑可以不顾经济利益(或没有经济利益)。今天千百万人去买标名牛仔裤,而这种牛仔裤的价格是同样耐穿的普通牛仔裤的两倍——因为标名商标的社会声望的价值超过了额外的花费。同样,日本继续使用它的麻烦得吓死人的汉字书写系统,而不愿使用效率高的字母或日本自己的效率高的假名音节文字——因为与汉字体系连在一起的社会声望实在太大了。

Still another factor is compatibility with vested interests. This book, like probably every other typed document you have ever read, was typed with a QWERTY keyboard, named for the left-most six letters in its upper row. Unbelievable as it may now sound, that keyboard layout was designed in 1873 as a feat of anti-engineering. It employs a whole series of perverse tricks designed to force typists to type as slowly as possible, such as scattering the commonest letters over all keyboard rows and concentrating them on the left side (where right-handed people have to use their weaker hand). The reason behind all of those seemingly counterproductive features is that the typewriters of 1873 jammed if adjacent keys were struck in quick succession, so that manufacturers had to slow down typists. When improvements in typewriters eliminated the problem of jamming, trials in 1932 with an efficiently laid-out keyboard showed that it would let us double our typing speed and reduce our typing effort by 95 percent. But QWERTY keyboards were solidly entrenched by then. The vested interests of hundreds of millions of QWERTY typists, typing teachers, typewriter and computer salespeople, and manufacturers have crushed all moves toward keyboard efficiency for over 60-years.

另一个因素是是否符合既得利益。本书同你读过的大概每一份别的打印文件一样,都是用标准打字机键盘打印出来的,这种键盘是因其上排最左面的6个字母而得名的。虽然现在听起来令人难以置信,打字机键盘的这种安排是在1873年作为一种反工程业绩而设计出来的。它使用了一系列旨在迫使打字的人尽可能放慢打字速度的故意作对的花招,如把最常用的字母键全都拆散而集中在左边(用惯右手的人必须用他们不习惯的左手)。这些似乎产生相反效果的特点的真实原因是:如果在1873年发明的这种打字机上连续快速敲击相邻的键,会使这些键互相卡在一起,所以制造打字机的人不得不使打字的人把打字的速度放慢。当打字机的改进解决卡键这个问题后,1932年对为提高效率而设计的键盘进行的试验表明,它可以成倍地提高我们的打字速度,把我们打字所花的气力减少95%。但到这时,标准打字机键盘的千百万个打字员、教打字的人、打字机和电脑推销员以及打字机生产厂商的既得利益,60多年来压制了提高打字机键盘效率的所有行动。

While the story of the QWERTY keyboard may sound funny, many similar cases have involved much heavier economic consequences. Why does Japan now dominate the world market for transistorized electronic consumer products, to a degree that damages the United States's balance of payments with Japan, even though transistors were invented and patented in the United States? Because Sony bought transistor licensing rights from Western Electric at a time when the American electronics consumer industry was churning out vacuum tube models and reluctant to compete with its own products. Why were British cities still using gas street lighting into the 1920s, long after U.S. and German cities had converted to electric street lighting? Because British municipal governments had invested heavily in gas lighting and placed regulatory obstacles in the way of the competing electric light companies.

虽然这个关于标准打字机键盘的故事听起来可能有点滑稽,但许多同样的例子却涉及重大得多的经济后果。虽然晶体管是在美国发明和取得专利权的,但为什么现在却是日本控制了世界晶体管化电子消费产品市场,以致破坏了美国与日本的国际收支平衡?因为就在美国的电子器件消费工业拼命生产真空管并且不愿与自己的产品竞争的时候,日本的索尼公司购买了西方电气公司的特许权。为什么英国的城市直到20世纪20年代,在美国和德国城市已经改用电灯为街道照明之后很久,仍在使用煤气为街道照明?因为英国的一些市政府已对煤气照明进行了大量投资,从而对竞争的电灯公司设置了行政管理方面的障碍。

The remaining consideration affecting acceptance of new technologies is the ease with which their advantages can be observed. In A.D. 1340, when firearms had not yet reached most of Europe, England's earl of Derby and earl of Salisbury happened to be present in Spain at the battle of Tarifa, where Arabs used cannons against the Spaniards. Impressed by what they saw, the earls introduced cannons to the English army, which adopted them enthusiastically and already used them against French soldiers at the battle of Crécy six years later.

影响接受新技术的最后一种考虑,是新技术的优点能够很容易地看到。公元1340年,当火器还没有到达欧洲大部分地区时,英格兰的德比伯爵和索尔兹伯里伯爵碰巧遇上了西班牙的塔里法战役,阿拉伯人在战斗中对西班牙人使用了大炮。这两位伯爵对他们所看到的事印象深刻,于是把大炮引进英国军队,而英国军队热情地采用了大炮,并于6年后在克勒西战役中把它们用来对付法国士兵。

THUS, WHEELS, DESIGNER jeans, and QWERTY keyboards illustrate the varied reasons why the same society is not equally receptive to all inventions. Conversely, the same invention's reception also varies greatly among contemporary societies. We are all familiar with the supposed generalization that rural Third World societies are less receptive to innovation than are Westernized industrial societies. Even within the industrialized world, some areas are much more receptive than others. Such differences, if they existed on a continental scale, might explain why technology developed faster on some continents than on others. For instance, if all Aboriginal Australian societies were for some reason uniformly resistant to change, that might account for their continued use of stone tools after metal tools had appeared on every other continent. How do differences in receptivity among societies arise?

因此,轮子、标名牛仔裤和标准打字机键盘说明了同一个社会对所有发明不是同样接受的不同原因。反过来说,对同一发明的接受力在同时代的社会中也是大不相同的。我们全都熟悉那个想象出来的普遍规律,即第三世界农村社会不像西方化了的工业社会那样容易接受新事物。即使在工业化的世界内,某些地区的接受能力要比另一些地区强得多。如果在整个大陆范围内存在着这种差异,那么它们也许能说明为什么某些大陆的技术发展要快于其他大陆。例如,如果澳大利亚的所有土著社会由于某种原因一律抵制变革,那也许能说明为什么当金属工具在其他每一个大陆出现后它们仍然在使用石器。社会之间在接受能力方面的差异是怎样产生的呢?

A laundry list of at least 14 explanatory factors has been proposed by historians of technology. One is long life expectancy, which in principle should give prospective inventors the years necessary to accumulate technical knowledge, as well as the patience and security to embark on long development programs yielding delayed rewards. Hence the greatly increased life expectancy brought by modern medicine may have contributed to the recently accelerating pace of invention.

技术史家们已经提出了一长串至少14个说明性因素。一个因素是预期寿命变长了,这在原则上应能使未来的发明家不仅有耐心和有把握去制订长期的、延期得益的开发计划,而且也使他们可以有多年时间去积累技术知识。因此,现代医药带来的大大延长了的期望寿命,可能加快了近来发明速度的步伐。

The next five factors involve economics or the organization of society: (1) The availability of cheap slave labor in classical times supposedly discouraged innovation then, whereas high wages or labor scarcity now stimulate the search for technological solutions. For example, the prospect of changed immigration policies that would cut off the supply of cheap Mexican seasonal labor to Californian farms was the immediate incentive for the development of a machine-harvestable variety of tomatoes in California. (2) Patents and other property laws, protecting ownership rights of inventors, reward innovation in the modern West, while the lack of such protection discourages it in modern China. (3) Modern industrial societies provide extensive opportunities for technical training, as medieval Islam did and modern Zaire does not. (4) Modern capitalism is, and the ancient Roman economy was not, organized in a way that made it potentially rewarding to invest capital in technological development. (5) The strong individualism of U.S. society allows successful inventors to keep earnings for themselves, whereas strong family ties in New Guinea ensure that someone who begins to earn money will be joined by a dozen relatives expecting to move in and be fed and supported.

其次的5个因素涉及社会的经济和组织:(1)古典时期可以得到廉价的奴隶劳动,这一点大概妨碍了当时的发明创造,而现在的高工资或劳动力短缺,对寻求技术解决办法起了刺激作用。例如,移民政策的改变,可能会切断加利福尼亚农场的廉价的墨西哥季节工的来源,但这种可能性鼓励了在加利福尼亚去开发可以用机器收获的番茄品种。(2)在现代的西方,保护发明者的所有权的专利权和其他财产法奖励发明,而在现代的中国,缺乏这种保护妨碍了发明。(3)现代工业社会提供了大量的技术培训的机会,这一点中世纪的伊斯兰教国家做到了,而现代的扎伊尔则没有做到。(4)和古罗马的经济不同,现代资本主义制度使投资技术开发有可能得到回报。(5)美国社会强烈的个人主义允许有成就的发明者为自己赚钱,而新几内亚牢固的家族关系则确保了一个人一旦开始赚钱就要同十几个指望搬来同吃同住的亲戚一起分享。

Another four suggested explanations are ideological, rather than economic or organizational: (1) Risk-taking behavior, essential for efforts at innovation, is more widespread in some societies than in others. (2) The scientific outlook is a unique feature of post-Renaissance European society that has contributed heavily to its modern technological preeminence. (3) Tolerance of diverse views and of heretics fosters innovation, whereas a strongly traditional outlook (as in China's emphasis on ancient Chinese classics) stifles it. (4) Religions vary greatly in their relation to technological innovation: some branches of Judaism and Christianity are claimed to be especially compatible with it, while some branches of Islam, Hinduism, and Brahmanism may be especially incompatible with it.

另外4个想得到的解释是意识形态方面的,不是经济或组织方面的:(1)为创新努力必不可少的冒险行为,在某些社会里比在另一些社会里普遍。(2)科学观点是文艺复兴后欧洲社会的独有特色,对于欧洲社会现代技术的卓越地位来说,这种特色确是功不可没。(3)对各种观点和异端观点的宽容促进了创新,而浓厚的传统观点(如中国强调中国古代的经典)则扼杀了创新。(4)宗教在其与技术创新的关系上差异很大:犹太教和基督教的某些教派据说与技术创新特别能够相容,而伊斯兰教、印度教和婆罗门教的某些教派可能与技术创新特别不能相容。

All ten of these hypotheses are plausible. But none of them has any necessary association with geography. If patent rights, capitalism, and certain religions do promote technology, what selected for those factors in postmedieval Europe but not in contemporary China or India?

所有这10个假设似乎都说得通。但其中没有一个与地理有任何必然的联系。如果专利权、资本主义和某些宗教真的对技术起了促进作用,那么又是什么决定了这些因素在中世纪后的欧洲出现,而不是在同时代的中国或印度出现?

At least the direction in which those ten factors influence technology seems clear. The remaining four proposed factors—war, centralized government, climate, and resource abundance—appear to act inconsistently: sometimes they stimulate technology, sometimes they inhibit it. (1) Throughout history, war has often been a leading stimulant of technological innovation. For instance, the enormous investments made in nuclear weapons during World War II and in airplanes and trucks during World War I launched whole new fields of technology. But wars can also deal devastating setbacks to technological development. (2) Strong centralized government boosted technology in late-19th-century Germany and Japan, and crushed it in China after A.D. 1500. (3) Many northern Europeans assume that technology thrives in a rigorous climate where survival is impossible without technology, and withers in a benign climate where clothing is unnecessary and bananas supposedly fall off the trees. An opposite view is that benign environments leave people free from the constant struggle for existence, free to devote themselves to innovation. (4) There has also been debate over whether technology is stimulated by abundance or by scarcity of environmental resources. Abundant resources might stimulate the development of inventions utilizing those resources, such as water mill technology in rainy northern Europe, with its many rivers—but why didn't water mill technology progress more rapidly in even rainier New Guinea? The destruction of Britain's forests has been suggested as the reason behind its early lead in developing coal technology, but why didn't deforestation have the same effect in China?

至少,这10个因素影响技术的方向似乎是清楚的。其余4个拟议中的因素——战争、集中统一的政府、气候和丰富的资源——所起的作用似乎是不一致的:有时候它们促进技术,有时候它们抑制技术。(1)在整个历史上,战争常常是促进技术革新的主要因素。例如,在第二次世界大战期间对核武器和第一次世界大战期间对飞机和卡车的巨额投资,开创了整个新的技术领域。但战争也能给技术发展带来破坏性极大的挫折。(2)强有力的集中统一的政府在19世纪后期的德国和日本对技术起了推动作用,而在公元1500年后的中国则对技术起了抑制作用。(3)许多北欧人认为,在气候条件严峻的地方,技术能够繁荣发展,因为在那里没有技术就不能生存,而在温和的气候下,技术则会枯萎凋零,因为那里不需要穿衣,而香蕉大概也会从树上掉下来。一种相反的观点则认为,有利的环境使人们用不着为生存进行不懈的斗争,而可以一门心思地去从事创新活动。(4)人们也一直在争论,促进技术发展的究竟是环境资源的丰富还是环境资源的短缺。丰富的资源可以促进利用这些资源的发明的发展,例如在有许多河流的多雨的北欧地区的水磨技术——但为什么水磨技术却没有在甚至更多雨的新几内亚更迅速地发展起来?有人认为英国森林遭到破坏是它很早就在采煤技术方面领先的原因,但为什么在中国滥伐森林却没有产生同样的结果呢?

This discussion does not exhaust the list of reasons proposed to explain why societies differ in their receptivity to new technology. Worse yet, all of these proximate explanations bypass the question of the ultimate factors behind them. This may seem like a discouraging setback in our attempt to understand the course of history, since technology has undoubtedly been one of history's strongest forces. However, I shall now argue that the diversity of independent factors behind technological innovation actually makes it easier, not harder, to understand history's broad pattern.

关于社会在接受新技术方面为什么会存在差异,上面的讨论并未穷尽为解释这个问题而提出来的各种原因。更糟的是,所有这些大致准确的解释都没有考虑这些解释背后的终极因素。这看起来也许就好像我们想要了解历史进程的尝试遭到了一次令人灰心丧气的挫折,因为技术毫无疑问一直是历史的最强大的推动力之一。然而,现在我要说,影响技术创新的独立因素是多种多样的,而这一点实际上使了解历史的广泛模式变得不是更困难,而是更容易了。

FOR THE PURPOSES of this book, the key question about the laundry list is whether such factors differed systematically from continent to continent and thereby led to continental differences in technological development. Most laypeople and many historians assume, expressly or tacitly, that the answer is yes. For example, it is widely believed that Australian Aborigines as a group shared ideological characteristics contributing to their technological backwardness: they were (or are) supposedly conservative, living in an imagined past Dreamtime of the world's creation, and not focused on practical ways to improve the present. A leading historian of Africa characterized Africans as inward looking and lacking Europeans' drive for expansion.

就本书所讨论的问题而言,这一长串问题中的主要问题是:影响技术创新的这些因素在大陆与大陆之间是否存在着全面的差异,因而导致了各大陆在技术发展方面的差异。大多数外行人和许多历史学家都认为答案是肯定的,有的是明确表示,有的是心照不宣。例如,人们普遍认为,澳大利亚土著作为一个群体,在意识形态方面具有导致他们技术落后的共同特点:他们过去(或现在)大概都是保守的,生活在一种想象中的创造世界的黄金时代,而不去注意改善现在的实际方法。一位研究非洲的主要历史学家则把非洲人说成是性格内向,缺乏欧洲人的那种扩张欲望。

But all such claims are based on pure speculation. There has never been a study of many societies under similar socioeconomic conditions on each of two continents, demonstrating systematic ideological differences between the two continents' peoples. The usual reasoning is instead circular: because technological differences exist, the existence of corresponding ideological differences is inferred.

但是,所有这类说法都是以纯粹的猜测为基础的。对两个大陆中每一个大陆上具有相同社会经济条件的许多社会,还不曾有人进行过研究,以证明这两个大陆民族之间的全面的意识形态差异。人们通常使用的都是循环论证:由于存在技术上的差异,因此可以推断出相应的意识形态上的差异。

In reality, I regularly observe in New Guinea that native societies there differ greatly from each other in their prevalent outlooks. Just like industrialized Europe and America, traditional New Guinea has conservative societies that resist new ways, living side by side with innovative societies that selectively adopt new ways. The result, with the arrival of Western technology, is that the more entrepreneurial societies are now exploiting Western technology to overwhelm their conservative neighbors.

事实上,我经常在新几内亚观察到,那里的土著社会在流行观点上彼此差异很大。就像工业化的欧洲和美国一样,传统的新几内亚也有抵制新的生活方式的保守社会,尽管它们同一些有选择地采纳了新的生活方式的富于创造性的社会生活在一起。结果,随着西方技术的输入,那些比较有创新精神的社会现在正利用西方的技术来征服它们的保守的邻居。

For example, when Europeans first reached the highlands of eastern New Guinea, in the 1930s, they “discovered” dozens of previously uncontacted Stone Age tribes, of which the Chimbu tribe proved especially aggressive in adopting Western technology. When Chimbus saw white settlers planting coffee, they began growing coffee themselves as a cash crop. In 1964 I met a 50-year-old Chimbu man, unable to read, wearing a traditional grass skirt, and born into a society still using stone tools, who had become rich by growing coffee, used his profits to buy a sawmill for $100,000 cash, and bought a fleet of trucks to transport his coffee and timber to market. In contrast, a neighboring highland people with whom I worked for eight years, the Daribi, are especially conservative and uninterested in new technology. When the first helicopter landed in the Daribi area, they briefly looked at it and just went back to what they had been doing; the Chimbus would have been bargaining to charter it. As a result, Chimbus are now moving into the Daribi area, taking it over for plantations, and reducing the Daribi to working for them.

例如,当欧洲人于20世纪30年代第一次到达新几内亚东部高原地区时,他们“发现了”几十个过去从未与外界接触过的石器时代的部落,其中钦布部落在采用西方技术方面特别积极。当钦布人看到白人移民种植咖啡,他们也开始把咖啡当作经济作物来种植。1964年,我遇见了一个50岁的钦布男子,他不识字,穿着传统的草裙。虽然他出生在一个仍然使用石器的社会,但却靠种咖啡发了财。他用赚来的10万美元现款买下了一个锯木厂,还买下了一队卡车,用来把他的咖啡和木材运往市场。相比之下,同我一起工作8年之久的一个毗邻的高原民族——达里比族,就特别保守,对新技术毫无兴趣。当第一架直升机在达里比人的地区降落时,他们只是很快地看了它一眼,然后回去继续干他们的活;如果是钦布人,他们就会为租用它来讨价还价。结果,钦布人现在正迁入达里比人的地区,把他们的土地接收过去改为种植园,并把达里比人变成为他们干活的劳工。

On every other continent as well, certain native societies have proved very receptive, adopted foreign ways and technology selectively, and integrated them successfully into their own society. In Nigeria the Ibo people became the local entrepreneurial equivalent of New Guinea's Chimbus. Today the most numerous Native American tribe in the United States is the Navajo, who on European arrival were just one of several hundred tribes. But the Navajo proved especially resilient and able to deal selectively with innovation. They incorporated Western dyes into their weaving, became silversmiths and ranchers, and now drive trucks while continuing to live in traditional dwellings.

其他每一个大陆都有这种情况,某些土著社会证明有很强的接受力,它们有选择地采纳外来的生活方式和技术,并成功地使之融入自己的社会。在尼日利亚,伊博族同新几内亚的钦布族一样,成了当地富于进取心的族群。今天美国人数最多的印第安部落是纳瓦霍族,在欧洲人来到时,他们不过是几百个部落中的一个。但纳瓦霍人的适应能力特别强,并能有选择地对待新事物。他们把西方的染料和自己的纺织结合起来,他们做银匠和农场工人,现在虽然仍住在传统的住宅里,但已学会了开卡车。

Among the supposedly conservative Aboriginal Australians as well, there are receptive societies along with conservative ones. At the one extreme, the Tasmanians continued to use stone tools superseded tens of thousands of years earlier in Europe and replaced in most of mainland Australia too. At the opposite extreme, some aboriginal fishing groups of southeastern Australia devised elaborate technologies for managing fish populations, including the construction of canals, weirs, and standing traps.

同样,在据称保守的澳大利亚土著中,既有接受能力强的社会,也有保守的社会。一个极端是塔斯马尼亚人,他们仍旧在使用石器,而这种工具在几万年前的欧洲即已为别的工具所代替,就是在澳洲大陆的大部分地区也已不再使用。另一极端是澳大利亚东南部的一些以捕鱼为生的土著群体,他们发明了管理鱼群的复杂技术,包括修建沟渠、鱼梁和渔栅。

Thus, the development and reception of inventions vary enormously from society to society on the same continent. They also vary over time within the same society. Nowadays, Islamic societies in the Middle East are relatively conservative and not at the forefront of technology. But medieval Islam in the same region was technologically advanced and open to innovation. It achieved far higher literacy rates than contemporary Europe; it assimilated the legacy of classical Greek civilization to such a degree that many classical Greek books are now known to us only through Arabic copies; it invented or elaborated windmills, tidal mills, trigonometry, and lateen sails; it made major advances in metallurgy, mechanical and chemical engineering, and irrigation methods; and it adopted paper and gunpowder from China and transmitted them to Europe. In the Middle Ages the flow of technology was overwhelmingly from Islam to Europe, rather than from Europe to Islam as it is today. Only after around A.D. 1500 did the net direction of flow begin to reverse.

因此,即使在同一个大陆上,各社会之间在发展和接受新事物方面也是大不相同的。即使是在同一个社会内,在时间上也会有所不同。现在,中东的伊斯兰社会相对而言比较保守,并不居于技术的最前列。但同一地区的中世纪伊斯兰教社会在技术上却是先进的,是能够接受新事物的。它的识字率比同时代的欧洲高得多;它吸收了古典的希腊文明的遗产,以致许多古典的希腊书籍只是通过阿拉伯文的译本才为我们所知;它发明了或精心制作了风车、用潮水推动的碾磨、三角学和大三角帆;它在冶金术、机械工程、化学工程和灌溉方法等方面取得了重大的进步;它采用了中国的纸和火药,又把它们传到欧洲。在中世纪,技术绝大多数是从伊斯兰世界流向欧洲,而不是像今天那样从欧洲流向伊斯兰世界。只是在公元1500年左右以后,技术的最终流向才开始逆转。

Innovation in China too fluctuated markedly with time. Until around A.D. 1450, China was technologically much more innovative and advanced than Europe, even more so than medieval Islam. The long list of Chinese inventions includes canal lock gates, cast iron, deep drilling, efficient animal harnesses, gunpowder, kites, magnetic compasses, movable type, paper, porcelain, printing (except for the Phaistos disk), sternpost rudders, and wheelbarrows. China then ceased to be innovative for reasons about which we shall speculate in the Epilogue. Conversely, we think of western Europe and its derived North American societies as leading the modern world in technological innovation, but technology was less advanced in western Europe than in any other “civilized” area of the Old World until the late Middle Ages.

中国的发明创造也是引人注目地随着时间而起伏不定。直到公元1450年左右,中国在技术上比欧洲更富于革新精神,也先进得多,甚至也大大超过了中世纪的伊斯兰世界。中国的一系列发明包括运河闸门、铸铁、深钻技术、有效的牲口挽具、火药、风筝、磁罗盘、活字、瓷器、印刷(不算菲斯托斯圆盘)、船尾舵和独轮车。接着,中国就不再富于革新精神,其原因我们将在本书的后记中加以推断。相反,我们倒是把西欧及其衍生的北美社会看作是领导了现代世界的技术创新,但直到中世纪后期,西欧的技术仍然没有旧大陆任何其他“文明”地区那样先进。

Thus, it is untrue that there are continents whose societies have tended to be innovative and continents whose societies have tended to be conservative. On any continent, at any given time, there are innovative societies and also conservative ones. In addition, receptivity to innovation fluctuates in time within the same region.

因此,认为有些大陆的社会总是富于创新精神,有些大陆的社会总是趋于保守,这种说法是不正确的。在任何时候,在任何大陆上都有富于创新精神的社会,也有保守的社会。此外,在同一个地区内,对新事物的接受能力迟早会产生波动。

On reflection, these conclusions are precisely what one would expect if a society's innovativeness is determined by many independent factors. Without a detailed knowledge of all of those factors, innovativeness becomes unpredictable. Hence social scientists continue to debate the specific reasons why receptivity changed in Islam, China, and Europe, and why the Chimbus, Ibos, and Navajo were more receptive to new technology than were their neighbors. To the student of broad historical patterns, though, it makes no difference what the specific reasons were in each of those cases. The myriad factors affecting innovativeness make the historian's task paradoxically easier, by converting societal variation in innovativeness into essentially a random variable. That means that, over a large enough area (such as a whole continent) at any particular time, some proportion of societies is likely to be innovative.

细想起来,如果一个社会的创新精神决定于许多独立的因素,那么这些结论就完全是人们可能期望的结论。如果对所有这些因素没有详尽的了解,创新精神就成了不可预测的东西。因此,一些社会科学家在继续争论:为什么在伊斯兰世界、中国和欧洲对新事物的接受能力会发生变化?为什么钦布人、伊博人和纳瓦霍人比他们的邻居更容易接受新事物?这些情况的具体原因是什么?然而,对研究广泛的历史模式的人来说,这些情况的具体原因是什么,这并不重要。影响创新精神的各种各样的因素,反而使历史学家的任务变得更加容易起来,他只要把社会之间在创新精神方面的差异转换为基本上一种随机变量就行了。这就是说,在任何特定时间里的一个相当大的区域内(如整个大陆),总会有一定数量的社会可能是富于创新精神的。

WHERE DO INNOVATIONS actually come from? For all societies except the few past ones that were completely isolated, much or most new technology is not invented locally but is instead borrowed from other societies. The relative importance of local invention and of borrowing depends mainly on two factors: the ease of invention of the particular technology, and the proximity of the particular society to other societies.

创新实际上来自何方?除了过去的几个完全与世隔绝的社会外,对所有社会来说,许多或大多数技术都不是当地发明的,而是从其他社会借来的。当地发明与借用技术的相对重要性,主要决定于两个因素:发明某个技术的容易程度以及某个社会与其他社会的接近程度。

Some inventions arose straightforwardly from a handling of natural raw materials. Such inventions developed on many independent occasions in world history, at different places and times. One example, which we have already considered at length, is plant domestication, with at least nine independent origins. Another is pottery, which may have arisen from observations of the behavior of clay, a very widespread natural material, when dried or heated. Pottery appeared in Japan around 14,000 years ago, in the Fertile Crescent and China by around 10,000 years ago, and in Amazonia, Africa's Sahel zone, the U.S. Southeast, and Mexico thereafter.

有些发明是通过处理天然原料而直接产生的。这些发明在世界史上的不同地点和时间曾有过多次独立的发展。有一个例子我们已经仔细考虑过了,这就是至少在9个地方独立进行的对植物的驯化。另一个例子是陶器。陶器的产生可能来自对黏土这种十分普遍的天然材料在晒干或受热时的变化所作的观察。陶器在大约14000年前出现于日本,不迟于大约1万年前出现于新月沃地和中国,以后又出现于亚马孙河地区、非洲的萨赫勒地带、美国东南部和墨西哥。

An example of a much more difficult invention is writing, which does not suggest itself by observation of any natural material. As we saw in Chapter 12, it had only a few independent origins, and the alphabet arose apparently only once in world history. Other difficult inventions include the water wheel, rotary quern, tooth gearing, magnetic compass, windmill, and camera obscura, all of which were invented only once or twice in the Old World and never in the New World.

一个困难得多的发明的例子是文字。文字的发明不是通过对任何天然材料的观察。我们在第十二章看到,文字只有几次是独立发明出来的,而字母在世界史上显然只产生过一次。其他一些困难的发明包括水轮、转磨、齿轮装置、磁罗盘、风车和照相机暗箱,所有这些在旧大陆只发明过一次或两次,而在新大陆则从未发明过。

Such complex inventions were usually acquired by borrowing, because they spread more rapidly than they could be independently invented locally. A clear example is the wheel, which is first attested around 3400 B.C. near the Black Sea, and then turns up within the next few centuries over much of Europe and Asia. All those early Old World wheels are of a peculiar design: a solid wooden circle constructed of three planks fastened together, rather than a rim with spokes. In contrast, the sole wheels of Native American societies (depicted on Mexican ceramic vessels) consisted of a single piece, suggesting a second independent invention of the wheel—as one would expect from other evidence for the isolation of New World from Old World civilizations.

这些复杂的发明通常是靠借用而得到的,因为它们的传播速度要比在当地独立发明的速度快。一个明显的例子是轮子。得到证明的最早的轮子于公元前3400年左右出现在黑海附近,接着在几个世纪内又在欧洲和亚洲的许多地区出现。所有这些旧大陆的早期轮子都有一种独特的设计:一个由3块厚木板拼成的实心圆盘,而不是一个带有辐条的轮圈。相比之下,印第安社会的唯一的一种轮子(画在墨西哥的陶器上)则是用一块木板做成的,由此可见,这是轮子的第二个独立的发明——就像人们从新大陆与旧大陆文明相隔绝的其他证据可以预料到的那样。

No one thinks that that same peculiar Old World wheel design appeared repeatedly by chance at many separate sites of the Old World within a few centuries of each other, after 7 million years of wheelless human history. Instead, the utility of the wheel surely caused it to diffuse rapidly east and west over the Old World from its sole site of invention. Other examples of complex technologies that diffused east and west in the ancient Old World, from a single West Asian source, include door locks, pulleys, rotary querns, windmills—and the alphabet. A New World example of technological diffusion is metallurgy, which spread from the Andes via Panama to Mesoamerica.

没有人认为,人类史在经过了没有轮子的700万年之后,不意在旧大陆的许多独立地点,于相隔不到几百年的时间内,竟多次出现了旧大陆的那种独特设计的轮子。实际上,想必是这种轮子的功用使它在旧大陆从唯一的发明地由东向西迅速传播。旧大陆在古代还有其他一些复杂的技术从一个西亚发源地由东向西传播的例子,其中包括门锁、滑轮、转磨、风车,还有字母。新大陆的技术传播的例子是冶金术,它是从安第斯山脉地区经巴拿马传到中美洲的。

When a widely useful invention does crop up in one society, it then tends to spread in either of two ways. One way is that other societies see or learn of the invention, are receptive to it, and adopt it. The second is that societies lacking the invention find themselves at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the inventing society, and they become overwhelmed and replaced if the disadvantage is sufficiently great. A simple example is the spread of muskets among New Zealand's Maori tribes. One tribe, the Ngapuhi, adopted muskets from European traders around 1818. Over the course of the next 15 years, New Zealand was convulsed by the so-called Musket Wars, as musketless tribes either acquired muskets or were subjugated by tribes already armed with them. The outcome was that musket technology had spread throughout the whole of New Zealand by 1833: all surviving Maori tribes now had muskets.

一个用途广泛的发明在一个社会出现后,接着它便往往以两种方式向外传播。一种方式是:其他社会看到或听说了这个发明,觉得可以接受,于是便采用了。另一种方式是:没有这种发明的社会发现与拥有这种发明的社会相比自己处于劣势,如果这种劣势大到一定程度,它们就会被征服并被取而代之。一个简单的例子是火枪在新西兰毛利人部落之间的传播。其中有一个叫恩加普希的部落于1818年左右从欧洲商人那里得到了火枪。在其后的15年中,新西兰被所谓的火枪战争搞得天翻地覆,没有火枪的部落要么也去弄到火枪,要么被已经用火枪武装起来的部落所征服。结果,到1833年火枪技术传遍了整个新西兰:所有幸存的毛利人部落这时都已有了火枪。

When societies do adopt a new technology from the society that invented it, the diffusion may occur in many different contexts. They include peaceful trade (as in the spread of transistors from the United States to Japan in 1954), espionage (the smuggling of silkworms from Southeast Asia to the Mideast in A.D. 552), emigration (the spread of French glass and clothing manufacturing techniques over Europe by the 200,000 Huguenots expelled from France in 1685), and war. A crucial case of the last was the transfer of Chinese papermaking techniques to Islam, made possible when an Arab army defeated a Chinese army at the battle of Talas River in Central Asia in A.D. 751, found some papermakers among the prisoners of war, and brought them to Samarkand to set up paper manufacture.

如果一些社会从发明某项新技术的社会采用了这项技术,这时技术传播的情况可能各不相同,其中包括和平贸易(如1954年晶体管从美国传播到日本)、间谍活动(公元552年家蚕从东南亚偷运进中东)、移民(1685年被从法国驱逐出去的20万胡格诺派教徒[5]把法国的玻璃和服装制作技术传播到整个欧洲)和战争。最后一个至关重要的例子,是中国的造纸术传到了伊斯兰世界。其所以可能,是由于公元751年阿拉伯军队在中亚的塔拉斯河战役中打败了中国军队,在战俘中发现了一些造纸工匠,于是就把他们带到了撒马尔罕建立了造纸业。[6]

In Chapter 12 we saw that cultural diffusion can involve either detailed “blueprints” or just vague ideas stimulating a reinvention of details. While Chapter 12 illustrated those alternatives for the spread of writing, they also apply to the diffusion of technology. The preceding paragraph gave examples of blueprint copying, whereas the transfer of Chinese porcelain technology to Europe provides an instance of long-drawn-out idea diffusion. Porcelain, a fine-grained translucent pottery, was invented in China around the 7th century A.D. When it began to reach Europe by the Silk Road in the 14th century (with no information about how it was manufactured), it was much admired, and many unsuccessful attempts were made to imitate it. Not until 1707 did the German alchemist Johann B ttger, after lengthy experiments with processes and with mixing various minerals and clays together, hit upon the solution and establish the now famous Meissen porcelain works. More or less independent later experiments in France and England led to Sèvres, Wedgwood, and Spode porcelains. Thus, European potters had to reinvent Chinese manufacturing methods for themselves, but they were stimulated to do so by having models of the desired product before them.

我们在第十二章看到,文化的传播可能是通过详尽的“蓝图”,也可能是通过刺激重新发明细节的模糊思想。虽然第十二章说明的是传播文字的办法,但这些办法对传播技术也同样适用。上一段举的是蓝图复制的例子,而中国的瓷器制造技术传往欧洲则是一个长期传播的例子。瓷器是一种纹理细密的半透明陶器,于公元7世纪左右在中国发明。当瓷器于14世纪开始经丝绸之路到达欧洲时(当时还不知道它的制造方法),人们对它赞赏不已,并为仿制它进行了多次不成功的尝试。直到1707年,德国的炼金术士约翰·伯特格尔在用许多制作方法和把各种矿物同黏土混合起来进行了长期的试验之后,才偶然发现了解决办法,从而建立了如今名闻遐迩的迈森瓷器工厂。后来在法国和英格兰进行的或多或少独立的试验,产生了塞夫勒陶瓷、韦奇伍德陶器和斯波德陶器。因此,欧洲的陶瓷工匠必须为他们自己对中国的制作方法进行再创造,但他们这样做是由于在他们的面前有那些完美无瑕的产品作为榜样从而刺激了他们的创作欲望。

DEPENDING ON THEIR geographic location, societies differ in how readily they can receive technology by diffusion from other societies. The most isolated people on Earth in recent history were the Aboriginal Tasmanians, living without oceangoing watercraft on an island 100 miles from Australia, itself the most isolated continent. The Tasmanians had no contact with other societies for 10,000 years and acquired no new technology other than what they invented themselves. Australians and New Guineans, separated from the Asian mainland by the Indonesian island chain, received only a trickle of inventions from Asia. The societies most accessible to receiving inventions by diffusion were those embedded in the major continents. In these societies technology developed most rapidly, because they accumulated not only their own inventions but also those of other societies. For example, medieval Islam, centrally located in Eurasia, acquired inventions from India and China and inherited ancient Greek learning.

社会的地理位置决定了它们接受来自其他社会的技术的容易程度是不同的。近代史上地球上最孤立的族群是塔斯马尼亚岛上的土著,他们生活在一个距离澳大利亚100英里的岛上,没有任何远洋水运工具,而澳大利亚本身就是一个最孤立的大陆。在过去1万年中,塔斯马尼亚人同其他社会没有任何接触,除了他们自己的发明外,他们没有得到过任何技术。澳大利亚人和新几内亚人由于有印度尼西亚岛群把他们同亚洲大陆隔开,所以只能从亚洲得到一点零星的发明。在发明的传播中最容易接受发明的社会是大陆上的一些根基深厚的社会。在这些社会中技术发展最快,因为它们不但积累了自己的发明,而且也积累了其他社会的发明。例如,中世纪的伊斯兰社会,由于位居欧亚大陆的中央,既得到了印度和中国的发明,又承袭了希腊的学术。

The importance of diffusion, and of geographic location in making it possible, is strikingly illustrated by some otherwise incomprehensible cases of societies that abandoned powerful technologies. We tend to assume that useful technologies, once acquired, inevitably persist until superseded by better ones. In reality, technologies must be not only acquired but also maintained, and that too depends on many unpredictable factors. Any society goes through social movements or fads, in which economically useless things become valued or useful things devalued temporarily. Nowadays, when almost all societies on Earth are connected to each other, we cannot imagine a fad's going so far that an important technology would actually be discarded. A society that temporarily turned against a powerful technology would continue to see it being used by neighboring societies and would have the opportunity to reacquire it by diffusion (or would be conquered by neighbors if it failed to do so). But such fads can persist in isolated societies.

技术传播和使技术传播成为可能的地理位置,这两者的重要性得到了一些从其他方面看简直难以理解的事实的充分证明,即有些社会竟然放弃了具有巨大作用的技术。我们往往想当然地认为,有用的技术一旦获得,就必然会流传下去,直到有更好的技术来取而代之。事实上,技术不但必须获得,而且也必须予以保持,而这也取决于许多不可预测的因素。任何社会都要经历一些社会运动和社会时尚,此时一些没有经济价值的东西变得有价值起来,而一些有用的东西也变得暂时失去了价值。今天,当地球上几乎所有社会相互联系在一起的时候,我们无法想象某种时尚会发展到使人们竟然抛弃一项重要的技术。一个暂时反对一项具有巨大作用的技术的社会会继续看到它在被毗连的社会所使用,而且也会有机会在这技术传播时重新得到它(或者,如果不能做到这一点,那就会被毗连的社会所征服)。但这种时尚会在孤立的社会中历久而不衰。

A famous example involves Japan's abandonment of guns. Firearms reached Japan in A.D. 1543, when two Portuguese adventurers armed with harquebuses (primitive guns) arrived on a Chinese cargo ship. The Japanese were so impressed by the new weapon that they commenced indigenous gun production, greatly improved gun technology, and by A.D. 1600 owned more and better guns than any other country in the world.

一个著名的例子是日本放弃枪支。火器在公元1543年到达日本,当时有两个葡萄牙人携带火绳枪(原始的枪)乘坐一艘中国货船抵达。日本人对这种新式武器印象很深,于是就开始在本地制造,从而大大地改进了枪支制造技术,到公元1600年已比世界上任何其他国家拥有更多更好的枪支。

But there were also factors working against the acceptance of firearms in Japan. The country had a numerous warrior class, the samurai, for whom swords rated as class symbols and works of art (and as means for subjugating the lower classes). Japanese warfare had previously involved single combats between samurai swordsmen, who stood in the open, made ritual speeches, and then took pride in fighting gracefully. Such behavior became lethal in the presence of peasant soldiers ungracefully blasting away with guns. In addition, guns were a foreign invention and grew to be despised, as did other things foreign in Japan after 1600. The samurai-controlled government began by restricting gun production to a few cities, then introduced a requirement of a government license for producing a gun, then issued licenses only for guns produced for the government, and finally reduced government orders for guns, until Japan was almost without functional guns again.

但也有一些因素不利于日本接受火器。这个国家有一个人数众多的武士阶层,对他们来说,刀是他们这个阶层的象征,也是艺术品(同时也是征服下层阶级的工具)。日本的战争以前都是使刀的武士之间面对面的个人搏斗,他们站在空地上,说几句老一套的话,然后以能体面地进行战斗而自豪。如果碰上农民出身的士兵手持枪支乒乒乓乓乱放一气,这种行为就是白送性命。而且,枪是外国的发明,越来越受到人们的鄙视,就像1600年后其他一些事物在日本受到鄙视一样。由武士控制的政府开始只允许几个城市生产枪支,然后又规定生产枪支需要获得政府的特许,再后来把许可证只发给为政府生产的枪支,最后又减少了政府对枪支的定货,直到日本又一次几乎没有实际可用的枪支。

Contemporary European rulers also included some who despised guns and tried to restrict their availability. But such measures never got far in Europe, where any country that temporarily swore off firearms would be promptly overrun by gun-toting neighboring countries. Only because Japan was a populous, isolated island could it get away with its rejection of the powerful new military technology. Its safety in isolation came to an end in 1853, when the visit of Commodore Perry's U.S. fleet bristling with cannons convinced Japan of its need to resume gun manufacture.

在同时代的欧洲也有一些鄙视枪支并竭力限制枪支使用的统治者。但这些限制措施在欧洲并未发生多大作用,因为任何一个欧洲国家,哪怕是短暂地放弃了火器,很快就会被用枪支武装起来的邻国打垮。只是因为日本是一个人口众多的孤立的海岛,它才没有因为拒绝这种具有巨大作用的新军事技术而受到惩罚。1853年,美国海军准将佩里率领装备有许多大炮的舰队访问日本,使日本相信它有必要恢复枪支的制造,直到这时,日本因孤立而得到安全的状况才宣告结束。

That rejection and China's abandonment of oceangoing ships (as well as of mechanical clocks and water-driven spinning machines) are well-known historical instances of technological reversals in isolated or semi-isolated societies. Other such reversals occurred in prehistoric times. The extreme case is that of Aboriginal Tasmanians, who abandoned even bone tools and fishing to become the society with the simplest technology in the modern world (Chapter 15). Aboriginal Australians may have adopted and then abandoned bows and arrows. Torres Islanders abandoned canoes, while Gaua Islanders abandoned and then readopted them. Pottery was abandoned throughout Polynesia. Most Polynesians and many Melanesians abandoned the use of bows and arrows in war. Polar Eskimos lost the bow and arrow and the kayak, while Dorset Eskimos lost the bow and arrow, bow drill, and dogs.

日本拒绝枪支和中国抛弃远洋船只(以及抛弃机械钟和水力驱动纺纱机),是历史上孤立或半孤立社会技术倒退的著名例子。其他技术倒退的事情,在史前期也发生过。极端的例子是塔斯马尼亚岛的土著,他们甚至放弃了骨器和捕鱼而成为现代世界技术最简陋的社会(第十五章)。澳大利亚土著可能采用过弓箭,后来又放弃了。托里斯海峡诸岛的岛民放弃了独木舟,而加瓦岛的岛民在放弃了独木舟后又重新采用。陶器在整个波利尼西亚都被放弃了。大多数波利尼西亚人和许多美拉尼西亚[7]人在战争中放弃使用弓箭。极地爱斯基摩人失去了弓箭和单人划子,而多塞特爱斯基摩人则失去了弓箭、弓钻和狗。

These examples, at first so bizarre to us, illustrate well the roles of geography and of diffusion in the history of technology. Without diffusion, fewer technologies are acquired, and more existing technologies are lost.

这些例子我们初听起来会觉得希奇古怪,但它们却很好地证明了技术史上地理条件和技术传播的作用。如果没有技术的传播,得到的技术会更少,而丢失的现有技术会更多。

BECAUSE TECHNOLOGY BEGETS more technology, the importance of an invention's diffusion potentially exceeds the importance of the original invention. Technology's history exemplifies what is termed an autocatalytic process: that is, one that speeds up at a rate that increases with time, because the process catalyzes itself. The explosion of technology since the Industrial Revolution impresses us today, but the medieval explosion was equally impressive compared with that of the Bronze Age, which in turn dwarfed that of the Upper Paleolithic.

由于技术能产生更多的技术,一项发明的传播的重要性可能会超过原来这项发明的重要性。技术史为所谓自我催化过程提供了例证:就是说,由于这过程对自身的催化,它就以一种与时俱增的速度而加快。工业革命以来的技术爆炸给我们今天的人留下了深刻的印象,但中世纪的技术爆炸与青铜时代相比,同样会给人以深刻的印象,而青铜时代的技术发展又使旧石器时代晚期的技术发展相形见绌。

One reason why technology tends to catalyze itself is that advances depend upon previous mastery of simpler problems. For example, Stone Age farmers did not proceed directly to extracting and working iron, which requires high-temperature furnaces. Instead, iron ore metallurgy grew out of thousands of years of human experience with natural outcrops of pure metals soft enough to be hammered into shape without heat (copper and gold). It also grew out of thousands of years of development of simple furnaces to make pottery, and then to extract copper ores and work copper alloys (bronzes) that do not require as high temperatures as does iron. In both the Fertile Crescent and China, iron objects became common only after about 2,000 years of experience of bronze metallurgy. New World societies had just begun making bronze artifacts and had not yet started making iron ones at the time when the arrival of Europeans truncated the New World's independent trajectory.

技术往往会催化自身的一个原因是:技术的进步决定于在这之前对一些比较简单的问题的掌握。例如,石器时代的农民不会直接开始炼铁和对铁进行加工,因为那必须有高温的炼铁炉才行。铁矿冶金术是人类几千年经验的结晶,人类开始时只是利用天然显露的软质纯金属(铜和金),在不需加热的情况下把它们捶打成形。它也是一些简单炉窑几千年发展的结果,这些炉窑用来烧制陶器,后来又被用来提炼铜矿和熔炼铜合金(青铜),因为做这些事不需要炼铁那样的高温。在新月沃地和中国,只是在有了大约2000年的青铜冶炼的经验之后,铁器才变得普遍起来。当欧洲人的到来缩短了新大陆的独立发展轨迹时,新大陆社会刚刚开始制造青铜器,还不曾开始制造铁器。

The other main reason for autocatalysis is that new technologies and materials make it possible to generate still other new technologies by recombination. For instance, why did printing spread explosively in medieval Europe after Gutenberg printed his Bible in A.D. 1455, but not after that unknown printer printed the Phaistos disk in 1700 B.C. The explanation is partly that medieval European printers were able to combine six technological advances, most of which were unavailable to the maker of the Phaistos disk. Of those advances—in paper, movable type, metallurgy, presses, inks, and scripts—paper and the idea of movable type reached Europe from China. Gutenberg's development of typecasting from metal dies, to overcome the potentially fatal problem of nonuniform type size, depended on many metallurgical developments: steel for letter punches, brass or bronze alloys (later replaced by steel) for dies, lead for molds, and a tin-zinc-lead alloy for type. Gutenberg's press was derived from screw presses in use for making wine and olive oil, while his ink was an oil-based improvement on existing inks. The alphabetic scripts that medieval Europe inherited from three millennia of alphabet development lent themselves to printing with movable type, because only a few dozen letter forms had to be cast, as opposed to the thousands of signs required for Chinese writing.

自我催化的另一个原因是:新技术和新材料通过重新结合可以产生更新的技术。例如,为什么印刷术的迅速传播发生在公元1455年谷登堡印刷了他的《圣经》之后的中世纪欧洲,而不是发生在公元前1700年那位无名的压印工印制了菲斯托斯圆盘之后?一部分原因是中世纪欧洲的印工能够把6项新技术结合起来,而这些新技术的大部分是菲斯托斯圆盘的制作者无法得到的。在这些技术进步——纸、活字、冶金术、印刷机、油墨和文字中,纸和关于活字的思想是从中国传到欧洲的。谷登堡发明的用金属模子铸字的办法克服了字体大小不一这种致命的问题,而他的办法又决定于冶金术的许多发展成果:用以冲压字母的钢、做字模用的黄铜或青铜合金(后来用钢代替)、做铸模用的铅和做活字用的锡锌铅合金。谷登堡的印刷机来自榨酒和橄榄油的螺旋压床,而他的油墨则是在现有的墨水中加油改进而成。中世纪欧洲从3000年的字母发展中继承的字母文字适合于用活字印刷,因为只需浇铸几十个字母就行了,不像中国文字那样需用几千个语言符号。

In all six respects, the maker of the Phaistos disk had access to much less powerful technologies to combine into a printing system than did Gutenberg. The disk's writing medium was clay, which is much bulkier and heavier than paper. The metallurgical skills, inks, and presses of 1700 B.C. Crete were more primitive than those of A.D. 1455 Germany, so the disk had to be punched by hand rather than by cast movable type locked into a metal frame, inked, and pressed. The disk's script was a syllabary with more signs, of more complex form, than the Roman alphabet used by Gutenberg. As a result, the Phaistos disk's printing technology was much clumsier, and offered fewer advantages over writing by hand, than Gutenberg's printing press. In addition to all those technological drawbacks, the Phaistos disk was printed at a time when knowledge of writing was confined to a few palace or temple scribes. Hence there was little demand for the disk maker's beautiful product, and little incentive to invest in making the dozens of hand punches required. In contrast, the potential mass market for printing in medieval Europe induced numerous investors to lend money to Gutenberg.

在所有这6个方面,若要把具有巨大作用的技术结合成一个印刷系统,菲斯托斯圆盘制作者能够得到的机会要比谷登堡少得多。这个圆盘的书写材料是黏土,其体积和重量都比纸大得多。公元前1700年的克里特岛在冶金技术、油墨和印刷机方面比公元1455年的德国都要原始,因此菲斯托斯圆盘必须用手来压印,而不是用装在金属框子里的浇铸活字加上油墨来印刷。圆盘上的文字是一种音节文字,比谷登堡使用的罗马字母符号更多,结构也更复杂。结果,菲斯托斯圆盘的压印技术比谷登堡的印刷机笨拙得多,比手写也好不了多少。除了所有这些技术上的缺点外,在印制菲斯托斯圆盘的那个时候,掌握书写知识的只有少数几个宫廷和寺庙抄写员。因此,对圆盘制作者的精美产品几乎没有什么需求,对投资制作所需要的几十个手压印模也几乎没有什么吸引力。相比之下,中世纪欧洲潜在的印刷品畅销市场则诱使许多投资者把钱借给谷登堡。

HUMAN TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPED from the first stone tools, in use by two and a half million years ago, to the 1996 laser printer that replaced my already outdated 1992 laser printer and that was used to print this book's manuscript. The rate of development was undetectably slow at the beginning, when hundreds of thousands of years passed with no discernible change in our stone tools and with no surviving evidence for artifacts made of other materials. Today, technology advances so rapidly that it is reported in the daily newspaper.

人类技术的发展是从不迟于250万年前使用的最早石器到1996年的激光印刷机,这种印刷机取代了我的业已过时的1992年的激光印刷机,并被用来印刷本书的手搞。开始时发展的速度慢得觉察不出来,几十万年过去了,我们的石器看不出有任何变化,用其他材料制造的物品也没有留下任何证据。今天,技术的发展非常迅速,报纸上天天都有报道。

In this long history of accelerating development, one can single out two especially significant jumps. The first, occurring between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, probably was made possible by genetic changes in our bodies: namely, by evolution of the modern anatomy permitting modern speech or modern brain function, or both. That jump led to bone tools, single-purpose stone tools, and compound tools. The second jump resulted from our adoption of a sedentary lifestyle, which happened at different times in different parts of the world, as early as 13,000 years ago in some areas and not even today in others. For the most part, that adoption was linked to our adoption of food production, which required us to remain close to our crops, orchards, and stored food surpluses.

在这漫长的加速发展的历史中,我们可以挑出两次意义特别重大的飞跃。第一次飞跃发生在10万年到5万年前,其所以能够发生,大概是由于我们身体的遗传变化,即人体的现代解剖学进化使现代语言或现代大脑功能或两者成为可能。这次飞跃产生了骨器、专用石器和复合工具。第二次飞跃来自我们选定的定居生活方式,这种生活方式在世界的不同地区发生的时间不同,在有些地区早在13000年前就发生了,在另一些地区即使在今天也还没有发生。就大多数情况而言,选定定居的生活方式是同我们采纳粮食生产联系在一起的,因为粮食生产要求我们留在我们的作物、果园和剩余粮食储备的近旁。

Sedentary living was decisive for the history of technology, because it enabled people to accumulate nonportable possessions. Nomadic hunter-gatherers are limited to technology that can be carried. If you move often and lack vehicles or draft animals, you confine your possessions to babies, weapons, and a bare minimum of other absolute necessities small enough to carry. You can't be burdened with pottery and printing presses as you shift camp. That practical difficulty probably explains the tantalizingly early appearance of some technologies, followed by a long delay in their further development. For example, the earliest attested precursors of ceramics are fired clay figurines made in the area of modern Czechoslovakia 27,000 years ago, long before the oldest known fired clay vessels (from Japan 14,000 years ago). The same area of Czechoslovakia at the same time has yielded the earliest evidence for weaving, otherwise not attested until the oldest known basket appears around 13,000 years ago and the oldest known woven cloth around 9,000 years ago. Despite these very early first steps, neither pottery nor weaving took off until people became sedentary and thereby escaped the problem of transporting pots and looms.

定居生活对技术史具有决定性的意义,因为这种生活使人们能够积累不便携带的财产。四处流浪的狩猎采集族群只能拥有可以携带的技术。如果你经常迁移而且又没有车辆或役畜,那么你的财产就只能是小孩、武器和最低限度的其他一些便于携带的小件必需品。你在变换营地时不能有陶器和印刷机之类的累赘。这种实际困难或许可以说明何以有些技术出现得逗人地早,接着停了很长时间才有了进一步的发展。例如,得到证明的最早的陶瓷艺术品是27000年前在现代捷克斯洛伐克地区用黏土烧制的人像,在时间上大大早于已知最早的用黏土烧制的容器(在14000年前的日本发现)。捷克斯洛伐克的同一地区在同一时间还出现了关于编织的迹象,但直到大约13000年前才出现了已知最早的篮子和大约9000年前出现了已知最早的布,这时最早编织的出现才得到了证明。尽管在很早的时候人们就已迈出了这几步,但在人们定居下来从而免去携带坛坛罐罐和织机的麻烦之前,无论是制陶还是编织都不会产生。

Besides permitting sedentary living and hence the accumulation of possessions, food production was decisive in the history of technology for another reason. It became possible, for the first time in human evolution, to develop economically specialized societies consisting of non-food-producing specialists fed by food-producing peasants. But we already saw, in Part 2 of this book, that food production arose at different times in different continents. In addition, as we've seen in this chapter, local technology depends, for both its origin and its maintenance, not only on local invention but also on the diffusion of technology from elsewhere. That consideration tended to cause technology to develop most rapidly on continents with few geographic and ecological barriers to diffusion, either within that continent or on other continents. Finally, each society on a continent represents one more opportunity to invent and adopt a technology, because societies vary greatly in their innovativeness for many separate reasons. Hence, all other things being equal, technology develops fastest in large productive regions with large human populations, many potential inventors, and many competing societies.

粮食生产使定居生活因而也使财产积累成为可能。不仅如此,由于另一个原因,粮食生产还在技术史上起了决定性的作用。它在人类进化中第一次使发展经济专业化社会成为可能,这种社会是由从事粮食生产的农民养活的不从事粮食生产的专门人员组成的。但我们在本书的第二部分中已经看到,粮食生产在不同的时间出现在不同的大陆。另外,我们在本章中也已看到,本地技术的发生和保持,不但要依靠本地的发明,而且也要依靠来自其他地方的技术传播。这个因素往往使技术在没有可能影响其传播的地理和生态障碍的大陆上发展得最快,而这种传播可能发生在这个大陆的内部,也可能发生在其他大陆。最后,一个大陆上的每一个社会都体现了发展技术和采用技术的进一步机会,因为各个社会在创新精神方面由于许多不同的原因而存在着巨大的差异。因此,在所有其他条件相同的情况下,技术发展最快的是那些人口众多、有许多潜在的发明家和许多互相竞争的社会的广大而富有成果的地区。

Let us now summarize how variations in these three factors—time of onset of food production, barriers to diffusion, and human population size—led straightforwardly to the observed intercontinental differences in the development of technology. Eurasia (effectively including North Africa) is the world's largest landmass, encompassing the largest number of competing societies. It was also the landmass with the two centers where food production began the earliest: the Fertile Crescent and China. Its east-west major axis permitted many inventions adopted in one part of Eurasia to spread relatively rapidly to societies at similar latitudes and climates elsewhere in Eurasia. Its breadth along its minor axis (north-south) contrasts with the Americas' narrowness at the Isthmus of Panama. It lacks the severe ecological barriers transecting the major axes of the Americas and Africa. Thus, geographic and ecological barriers to diffusion of technology were less severe in Eurasia than in other continents. Thanks to all these factors, Eurasia was the continent on which technology started its post-Pleistocene acceleration earliest and resulted in the greatest local accumulation of technologies.

现在,让我们来总结一下,粮食生产开始的时间、技术传播的障碍和人口的多寡这3大因素的变化,是怎样直接导致我们所看到的各大陆之间在技术发展方面的差异的。欧亚大陆(实际上也包括北非在内)是世界上最大的陆块,包含有数量最多的互相竞争的社会。它也是拥有粮食生产开始最早的两个中心的陆块,这两个中心就是新月沃地和中国。它的东西向的主轴线,使欧亚大陆一个地区采用的许多发明较快地传播到欧亚大陆具有相同纬度和气候的其他地区的社会。它的沿次轴线(南北轴线)的宽度,同美洲巴拿马地峡的狭窄形成了对照。它没有把美洲和非洲的主轴线切断的那种严重的生态障碍。因此,对技术传播的地理和生态障碍,在欧亚大陆没有在其他大陆那样严重。由于所有这些因素,后更新世技术的加速发展,在欧亚大陆开始得最早,从而导致了本地最大的技术积累。

North and South America are conventionally regarded as separate continents, but they have been connected for several million years, pose similar historical problems, and may be considered together for comparison with Eurasia. The Americas form the world's second-largest landmass, significantly smaller than Eurasia. However, they are fragmented by geography and by ecology: the Isthmus of Panama, only 40 miles wide, virtually transects the Americas geographically, as do the isthmus's Darien rain forests and the northern Mexican desert ecologically. The latter desert separated advanced human societies of Mesoamerica from those of North America, while the isthmus separated advanced societies of Mesoamerica from those of the Andes and Amazonia. In addition, the main axis of the Americas is north-south, forcing most diffusion to go against a gradient of latitude (and climate) rather than to operate within the same latitude. For example, wheels were invented in Mesoamerica, and llamas were domesticated in the central Andes by 3000 B.C., but 5,000 years later the Americas' sole beast of burden and sole wheels had still not encountered each other, even though the distance separating Mesoamerica's Maya societies from the northern border of the Inca Empire (1,200 miles) was far less than the 6,000 miles separating wheel- and horse-sharing France and China. Those factors seem to me to account for the Americas' technological lag behind Eurasia.

北美洲和南美洲在传统上被看作是两个不同的大陆,但它们连接在一起已有几百万年之久,它们提出了同样的历史问题,因此可以把它们放在一起来考虑,以便和欧亚大陆相比较。美洲构成了世界上第二大的陆块,但比欧亚大陆小得多。不过,它们在地理和生态上却支离破碎:巴拿马地峡宽不过40英里,等于在地理上把美洲给腰斩了,就像这个地峡上的达里安雨林和墨西哥北部的沙漠在生态上所做的那样。墨西哥北部的沙漠把中美洲人类的先进社会同北美洲的社会分隔开了,而巴拿马地峡则把中美洲的先进社会同安第斯山脉地区和亚马孙河地区的社会分隔开了。此外,美洲的主轴线是南北走向,从而使大部分的技术传播不得不逆纬度(和气候)的梯度而行,而不是在同一纬度内发生。例如,轮子是在中美洲发明的,而美洲驼是不迟于公元前3000年在安第斯山脉中部驯化的,但过了5000年,美洲的这唯一的役畜和唯一的轮子仍然没有碰头,虽然中美洲马雅社会同印加帝国北部边界之间的距离(1200英里)比同样有轮子和马匹的法国同中国之间6000英里的距离要短得多。在我看来,这些因素足以说明美洲在技术上落后于欧亚大陆这个事实。

Sub-Saharan Africa is the world's third largest landmass, considerably smaller than the Americas. Throughout most of human history it was far more accessible to Eurasia than were the Americas, but the Saharan desert is still a major ecological barrier separating sub-Saharan Africa from Eurasia plus North Africa. Africa's north-south axis posed a further obstacle to the diffusion of technology, both between Eurasia and sub-Saharan Africa and within the sub-Saharan region itself. As an illustration of the latter obstacle, pottery and iron metallurgy arose in or reached sub-Saharan Africa's Sahel zone (north of the equator) at least as early as they reached western Europe. However, pottery did not reach the southern tip of Africa until around A.D. 1, and metallurgy had not yet diffused overland to the southern tip by the time that it arrived there from Europe on ships.

非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区是世界上第三大的陆块,但比美洲小得多。在人类的大部分历史中,到欧亚大陆比到美洲容易多了,但撒哈拉沙漠却仍然是一个主要的生态障碍,把非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区同欧亚大陆和北非隔开。非洲的南北轴线造成了欧亚大陆与非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南地区之间以及撒哈拉沙漠以南地区本身内部技术传播的又一障碍。作为后一障碍的例子,陶器和炼铁术出现在或到达非洲撒哈拉沙漠以南的萨赫勒地带(赤道以北),至少同它们到达西欧一样早。然而,陶器直到公元元年才到达非洲的南端,而冶金术在从欧洲由海路到达非洲南端时,还不曾由陆路传播到那里。

Finally, Australia is the smallest continent. The very low rainfall and productivity of most of Australia makes it effectively even smaller as regards its capacity to support human populations. It is also the most isolated continent. In addition, food production never arose indigenously in Australia. Those factors combined to leave Australia the sole continent still without metal artifacts in modern times.

最后,澳大利亚是最小的一个大陆。澳大利亚大部分地区雨量稀少,物产贫乏,因此,就其所能养活的人口来说,它实际上就显然甚至更小。它也是一个最孤立的大陆。加之,粮食生产也从来没有在澳大利亚本地出现过。这些因素加在一起,就使澳大利亚成为唯一的在现代仍然没有金属制品的大陆。