CHAPTER 17

第十七章

SPEEDBOAT TO POLYNESIA

驶向波利尼西亚的快艇

PACIFIC ISLAND HISTORY IS ENCAPSULATED FOR ME IN AN incident that happened when three Indonesian friends and I walked into a store in Jayapura, the capital of Indonesian New Guinea. My friends' names were Achmad, Wiwor, and Sauakari, and the store was run by a merchant named Ping Wah. Achmad, an Indonesian government officer, was acting as the boss, because he and I were organizing an ecological survey for the government and had hired Wiwor and Sauakari as local assistants. But Achmad had never before been in a New Guinea mountain forest and had no idea what supplies to buy. The results were comical.

有一次,在印度尼西亚属新几内亚的首都查亚普拉,我和3位印度尼西亚朋友走进了一家铺子,这时发生了一件事。对我说来,这件事就是太平洋岛屿历史的缩影。我这3位朋友的名字分别是阿什马德、维沃尔和索阿卡里。这家铺子是一个名叫平瓦的商人开的。阿什马德是印度尼西亚政府官员,担任我们的头儿,因为他和我正在为政府组织一次生态调查,我们雇用了维沃尔和索阿卡里做本地的助手。但阿什马德从来没有到过新几内亚的山区森林,根本不知道该采办什么东西。这结果令人发笑。

At the moment that my friends entered the store, Ping Wah was reading a Chinese newspaper. When he saw Wiwor and Sauakari, he kept reading it but then shoved it out of sight under the counter as soon as he noticed Achmad. Achmad picked up an ax head, causing Wiwor and Sauakari to laugh, because he was holding it upside down. Wiwor and Sauakari showed him how to hold it correctly and to test it. Achmad and Sauakari then looked at Wiwor's bare feet, with toes splayed wide from a lifetime of not wearing shoes. Sauakari picked out the widest available shoes and held them against Wiwor's feet, but the shoes were still too narrow, sending Achmad and Sauakari and Ping Wah into peals of laughter. Achmad picked up a plastic comb with which to comb out his straight, coarse black hair. Glancing at Wiwor's tough, tightly coiled hair, he handed the comb to Wiwor. It immediately stuck in Wiwor's hair, then broke as soon as Wiwor pulled on the comb. Everyone laughed, including Wiwor. Wiwor responded by reminding Achmad that he should buy lots of rice, because there would be no food to buy in New Guinea mountain villages except sweet potatoes, which would upset Achmad's stomach—more hilarity.

在我的朋友们走进这家铺子的时候,平瓦正在读一份中文报纸。当他看见维沃尔和索阿卡里时,他继续读他的报纸,但他一看到阿什马德,就飞快地把报纸塞到柜台下面。阿什马德拿起了一把斧头,惹得维沃尔和索阿卡里笑了起来,因为他把斧头拿倒了。维沃尔和索阿卡里教给他怎样正确地握住斧柄砍东西。这时,阿什马德和索阿卡里注意到维沃尔的光脚丫子,因为他一辈子没有穿过鞋,所以脚趾头都向外张开。索阿卡里挑了一双最大的鞋往维沃尔的脚上套,但这双鞋仍然太小,这引得阿什马德、索阿卡里和平瓦笑声不断。阿什马德挑了一把塑料梳子来梳理他那又粗又黑的直发。他看了一眼维沃尔的浓密的鬈发,把梳子递给维沃尔。梳子立刻在头发里卡住,维沃尔一使劲,梳子就立即折断了。大家都笑了,维沃尔自己也笑了。接着维沃尔提醒阿什马德要买许多大米,因为在新几内亚的山村里除了甘薯买不到其他食物,而吃甘薯会使阿什马德的胃受不了——大家又笑了。

Despite all the laughter, I could sense the underlying tensions. Achmad was Javan, Ping Wah Chinese, Wiwor a New Guinea highlander, and Sauakari a New Guinea lowlander from the north coast. Javans dominate the Indonesian government, which annexed western New Guinea in the 1960s and used bombs and machine guns to crush New Guinean opposition. Achmad later decided to stay in town and to let me do the forest survey alone with Wiwor and Sauakari. He explained his decision to me by pointing to his straight, coarse hair, so unlike that of New Guineans, and saying that New Guineans would kill anyone with hair like his if they found him far from army backup.

笑归笑,我还是觉察到了潜在的紧张。阿什马德是爪哇人,平瓦是中国人,维沃尔是新几内亚高原人,而索阿卡里是新几内亚北部沿海低地人。爪哇人在印度尼西亚政府中大权独揽,而印度尼西亚政府于20世纪60年代并吞了新几内亚西部,并用炸弹和机关枪粉碎了新几内亚人的反抗。阿什马德后来决定留在城里,让我独自带着维沃尔和索阿卡里去做森林调查工作。他向我解释了他的决定,他指着他那和新几内亚人完全不同的粗直头发说,新几内亚人会杀死任何一个长着他这样头发的人,如果他们发现他远离军队的支持的话。

Ping Wah had put away his newspaper because importation of Chinese writing is nominally illegal in Indonesian New Guinea. In much of Indonesia the merchants are Chinese immigrants. Latent mutual fear between the economically dominant Chinese and politically dominant Javans erupted in 1966 in a bloody revolution, when Javans slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Chinese. As New Guineans, Wiwor and Sauakari shared most New Guineans' resentment of Javan dictatorship, but they also scorned each other's groups. Highlanders dismiss lowlanders as effete sago eaters, while lowlanders dismiss highlanders as primitive big-heads, referring both to their massive coiled hair and to their reputation for arrogance. Within a few days of my setting up an isolated forest camp with Wiwor and Sauakari, they came close to fighting each other with axes.

平瓦已经收起了他的报纸,因为输入中国印刷品在印度尼西亚属新几内亚在名义上是非法的。在印度尼西亚的很大一部分地区,商人都是中国移民。在经济上占支配地位的华人与政治上占支配地位的爪哇人之间潜伏着的相互恐惧在1966年爆发为一场流血的革命,当时爪哇人屠杀了成千上万的华人。维沃尔和索阿卡里是新几内亚人,他们也抱有大多数新几内亚人对爪哇人独裁统治所抱有的愤恨,但他们又互相瞧不起对方的群体。高原居民认为低地居民是光吃西谷椰子的无能之辈而不屑一顾,而低地居民也不把高原居民放在眼里,说他们是未开化的大头鬼,这是指他们那一头浓密的鬈发,也是指他们那出名的傲慢态度。我与维沃尔和索阿卡里建立了一个孤零零的森林营地还没有几天,他们差点儿用斧头干起架来。

Tensions among the groups that Achmad, Wiwor, Sauakari, and Ping Wah represent dominate the politics of Indonesia, the world's fourth-most-populous nation. These modern tensions have roots going back thousands of years. When we think of major overseas population movements, we tend to focus on those since Columbus's discovery of the Americas, and on the resulting replacements of non-Europeans by Europeans within historic times. But there were also big overseas movements long before Columbus, and prehistoric replacements of non-European peoples by other non-European peoples. Wiwor, Achmad, and Sauakari represent three prehistorical waves of people that moved overseas from the Asian mainland into the Pacific. Wiwor's highlanders are probably descended from an early wave that had colonized New Guinea from Asia by 40,000 years ago. Achmad's ancestors arrived in Java ultimately from the South China coast, around 4,000 years ago, completing the replacement there of people related to Wiwor's ancestors. Sauakari's ancestors reached New Guinea around 3,600 years ago, as part of that same wave from the South China coast, while Ping Wah's ancestors still occupy China.

阿什马德、维沃尔、索阿卡里和平瓦所代表的这些群体之间的紧张状况,主宰了印度尼西亚这个世界上第四位人口最多的国家的政治。现代的这种紧张状况的根源可以追溯到几千年前。我们在考虑海外重大的人口流动时,往往着重考虑哥伦布发现美洲以来的那些人口流动,以及由此而产生的在各个历史时期内欧洲人更替非欧洲人的情况。但在哥伦布之前很久也存在大规模的海外人口流动,而在史前期也已有了非欧洲人被其他非欧洲人所更替的现象。维沃尔、阿什马德和索阿卡里代表了史前时代从亚洲大陆进入太平洋的3次海外移民浪潮。维沃尔的高原地区居民可能是不迟于4万年前开拓新几内亚的大批早期亚洲移民的后代。阿什马德的祖先在大约4万年前最后从华南沿海到达,完成了对那里的与维沃尔的祖先有亲缘关系的人们的更替。索阿卡里的祖先大约在36000年前到达新几内亚,他们是来自华南沿海的同一批移民浪潮的一部分,而平瓦的祖先则仍然占据着中国。

The population movement that brought Achmad's and Sauakari's ancestors to Java and New Guinea, respectively, termed the Austronesian expansion, was among the biggest population movements of the last 6,000 years. One prong of it became the Polynesians, who populated the most remote islands of the Pacific and were the greatest seafarers among Neolithic peoples. Austronesian languages are spoken today as native languages over more than half of the globe's span, from Madagascar to Easter Island. In this book on human population movements since the end of the Ice Ages, the Austronesian expansion occupies a central place, as one of the most important phenomena to be explained. Why did Austronesian people, stemming ultimately from mainland China, colonize Java and the rest of Indonesia and replace the original inhabitants there, instead of Indonesians colonizing China and replacing the Chinese? Having occupied all of Indonesia, why were the Austronesians then unable to occupy more than a narrow coastal strip of the New Guinea lowlands, and why were they completely unable to displace Wiwor's people from the New Guinea highlands? How did the descendants of Chinese emigrants become transformed into Polynesians?

把阿什马德和索阿卡里的祖先分别带到爪哇和新几内亚的人口流动,被称为南岛人的扩张,这是过去6000年中发生的几次规模最大的人口流动之一。其中的一支成为波利尼西亚人,他们住在太平洋中最偏远的岛上,是新石器时代各族群中最伟大的航海者。南岛人今天所说的语言是分布最广的一种语言,从马达加斯加到复活节岛,覆盖了大半个地球。在本书中,关于自冰期结束以来的人口流动问题,南岛人的扩张占有中心的地位,因为这是需要予以解释的最重要的现象之一。为什么是最后来自大陆中国的南岛人在爪哇和印度尼西亚的其余地方殖民并更替了那里原来的居民,而不是印度尼西亚人在中国殖民并更替了中国人?南岛人在占据了整个印度尼西亚之后,为什么不能再占据新几内亚低地那一块沿海的狭长地带,为什么完全不能把维沃尔的族群从新几内亚高原地区赶走?中国移民的后代又是怎样变成波利尼西亚人的?

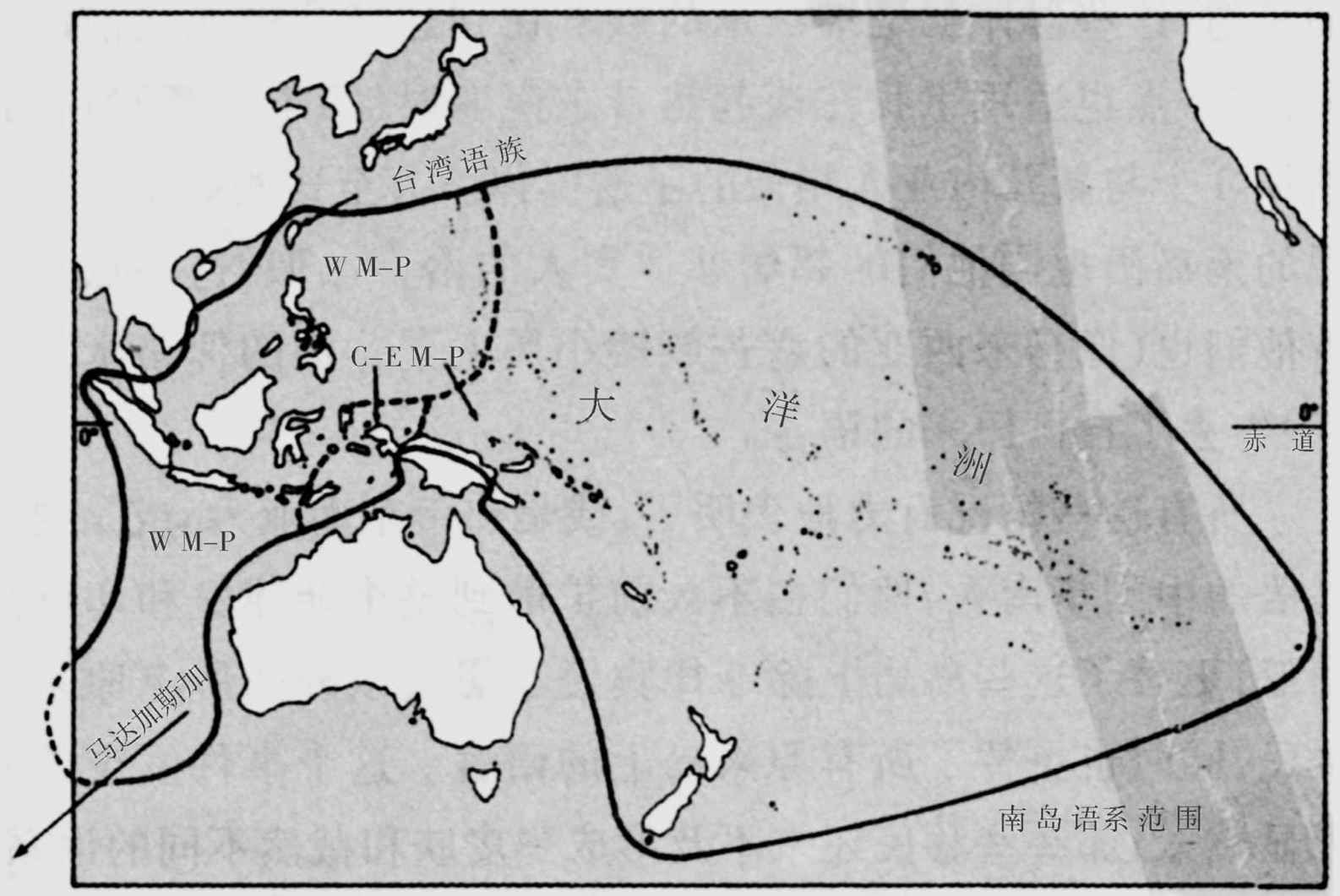

TODAY, THE POPULATION of Java, most other Indonesian islands (except the easternmost ones), and the Philippines is rather homogeneous. In appearance and genes those islands' inhabitants are similar to South Chinese, and even more similar to tropical Southeast Asians, especially those of the Malay Peninsula. Their languages are equally homogeneous: while 374 languages are spoken in the Philippines and western and central Indonesia, all of them are closely related and fall within the same sub-subfamily (Western Malayo-Polynesian) of the Austronesian language family. Austronesian languages reached the Asian mainland on the Malay Peninsula and in small pockets in Vietnam and Cambodia, near the westernmost Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo, but they occur nowhere else on the mainland (Figure 17.1). Some Austronesian words borrowed into English include “taboo” and “tattoo” (from a Polynesian language), “boondocks” (from the Tagalog language of the Philippines), and “amok,” “batik,” and “orangutan” (from Malay).

今天的爪哇岛、大部分其他印度尼西亚岛屿(最东端的一些岛屿除外)以及菲律宾群岛上的居民是颇为相似的。在外貌和遗传上,这些岛上的居民与华南的中国人相似,甚至与热带东南亚人更加相似,尤其与马来半岛的居民相似。他们的语言也同样相似:虽然在菲律宾群岛和印度尼西亚的西部及中部地区有374种语言,但它们全都有很近的亲缘关系,都属于南岛语系的同一个语支(西马来-波利尼西亚语支)。南岛语到达亚洲大陆的马来半岛、越南和柬埔寨的一些小块地区、印度尼西亚最西端的岛屿苏门答腊和婆罗洲附近,但在大陆的其他地方就再也没有这些语言了(图17.1)。南岛语中的一些词被借入英语,其中包括“taboo”(禁忌)和“tattoo”(文身)(来自波利尼西亚语)、“boondocks”(荒野)(来自菲律宾的他加禄语)、“amok”(杀人狂)、“batik”(蜡防印花法[1])和“orangutan”(猩猩)(来自马来语)。

That genetic and linguistic uniformity of Indonesia and the Philippines is initially as surprising as is the predominant linguistic uniformity of China. The famous Java Homo erectus fossils prove that humans have occupied at least western Indonesia for a million years. That should have given ample time for humans to evolve genetic and linguistic diversity and tropical adaptations, such as dark skins like those of many other tropical peoples—but instead Indonesians and Filipinos have light skins.

印度尼西亚和菲律宾在遗传和语言上的一致起初令人惊讶,就像中国在语言上的普遍一致令人惊讶一样。著名的爪哇人化石证明,人类至少在印度尼西亚西部居住了100万年之久。这应该使人类有充裕的时间逐步形成遗传和语言方面的差异和对热带的适应性变化,如像其他许多热带居民的那种黑皮肤——但印度尼西亚人和菲律宾人却肤色较浅。

Distribution of Austronesian languages

南岛语系诸语言分布图

Figure 17. 1. The Austronesian language family consists of four subfamilies, three of them confined to Taiwan and one (Malayo-Polynesian) widespread. The latter subfamily in turn consists of two sub-subfamilies, Western Malayo-Polynesian (= WM-P) and Central-Eastern Malayo- Polynesian (= C-EM-P). The latter sub-subfamily in turn consists of four sub-sub-subfamilies, the very widespread Oceanic one to the east and three others to the west in a much smaller area comprising Halmahera, nearby islands of eastern Indonesia, and the west end of New Guinea.

图17.1 南岛语系包括4个语族,其中3个都在台湾,另一个(马来-波利尼西亚语族)分布甚广。这后一个语族又包括两个语支——西马来-波利尼西亚语(=WM-P)和中-东马来-波利尼西亚语(=C-EM-P)。这后一个语支又包括4个亚语支,其中分布很广的大洋洲亚语支在东,另外3个在西,其分布地区小得多,包括哈尔马赫拉岛、印度尼西亚东部附近岛屿和新几内亚西端。

It is also surprising that Indonesians and Filipinos are so similar to tropical Southeast Asians and South Chinese in other physical features besides light skins and in their genes. A glance at a map makes it obvious that Indonesia offered the only possible route by which humans could have reached New Guinea and Australia 40,000 years ago, so one might naively have expected modern Indonesians to be like modern New Guineans and Australians. In reality, there are only a few New Guinean-like populations in the Philippine / western Indonesia area, notably the Negritos living in mountainous areas of the Philippines. As is also true of the three New Guinean-like relict populations that I mentioned in speaking of tropical Southeast Asia (Chapter 16), the Philippine Negritos could be relicts of populations ancestral to Wiwor's people before they reached New Guinea. Even those Negritos speak Austronesian languages similar to those of their Filipino neighbors, implying that they too (like Malaysia's Semang Negritos and Africa's Pygmies) have lost their original language.

同样令人惊讶的是,除了肤色较浅这一点外,在其他体貌特征和遗传方面,印度尼西亚人和菲律宾人同热带东南亚人和中国华南人非常相似。只要看一看地图就可清楚地知道,印度尼西亚提供了人类在4万年前到达新几内亚和澳大利亚的唯一可能的路线,因此人们可能天真地以为,现代的印度尼西亚人理应像现代的新几内亚人和澳大利亚人。事实上,在菲律宾/印度尼西亚西部地区,只有几个像新几内亚人的人群,特别是生活在菲律宾山区的矮小黑人。菲律宾的这些矮小黑人可能是一些群体的孑遗,这些群体就是维沃尔的族群在到达新几内亚之前的祖先,这一点也适用于我在谈起热带东南亚时(第十六章)所提到的那3个与新几内亚人相似的孑遗群体。甚至这些矮小黑人所说的南岛语也同他们的邻居菲律宾人的语言相似,这一点意味着他们也(像马来西亚的塞芒族矮小黑人和非洲的俾格米人一样)失去了自己原来的语言。

All these facts suggest strongly that either tropical Southeast Asians or South Chinese speaking Austronesian languages recently spread through the Philippines and Indonesia, replacing all the former inhabitants of those islands except the Philippine Negritos, and replacing all the original island languages. That event evidently took place too recently for the colonists to evolve dark skins, distinct language families, or genetic distinctiveness or diversity. Their languages are of course much more numerous than the eight dominant Chinese languages of mainland China, but are no more diverse. The proliferation of many similar languages in the Philippines and Indonesia merely reflects the fact that the islands never underwent a political and cultural unification, as did China.

所有这些情况有力地表明了,或是热带东南亚人,或是说南岛语的中国华南人,他们在不久前扩散到整个菲律宾和印度尼西亚,更替了这些岛屿上除菲律宾矮小黑人以外的所有原来的居民,同时也更替了所有原来岛上的语言。这个事件发生的时间显然太近,那些移民还来不及形成黑皮肤和截然不同的语系,也来不及形成遗传特征或遗传差异。他们的语言当然比大陆中国的8大语言多得多,但不再迥然不同。许多相似的语言在菲律宾和印度尼西亚增生,只是反映了这些岛屿从未像中国那样经历过政治和文化的统一。

Details of language distributions provide valuable clues to the route of this hypothesized Austronesian expansion. The whole Austronesian language family consists of 959 languages, divided among four subfamilies. But one of those subfamilies, termed Malayo-Polynesian, comprises 945 of those 959 languages and covers almost the entire geographic range of the Austronesian family. Before the recent overseas expansion of Europeans speaking Indo-European languages, Austronesian was the most widespread language family in the world. That suggests that the Malayo-Polynesian subfamily differentiated recently out of the Austronesian family and spread far from the Austronesian homeland, giving rise to many local languages, all of which are still closely related because there has been too little time to develop large linguistic differences. For the location of that Austronesian homeland, we should therefore look not to MalayoPolynesian but to the other three Austronesian subfamilies, which differ considerably more from each other and from Malayo-Polynesian than the sub-subfamilies of Malayo-Polynesian differ among each other.

语言分布的详细情况为这种假设的南岛人扩张的路线提供了有价值的线索。整个南岛语系包括959种语言,分为4个语族。但其中一个被称为马来-波利尼西亚语的语族包括了这959种语言中的945种,几乎覆盖了南岛语系整个地理分布范围。在说印欧语的欧洲人最近的海外扩张之前,南岛语是世界上分布最广的语系。这表明,马来-波利尼西亚语族最近从南岛语系分化出来,从南岛语的故乡向远方传播,从而产生了许多地方性语言,但仍然都是近亲语言,因为时间太短,还不能形成巨大的语言差异。至于南岛语的故乡究竟在何处,我们不应因此就把目光投向马来-波利尼西亚语族,而应投向南岛语系的另外3个语族,它们彼此之间的差异以及与马来-波利尼西亚语族的差异,要大大多于马来-波利尼西亚语族的各个语支之间的差异。

It turns out that those three other subfamilies have coincident distributions, all of them tiny compared with the distribution of Malayo-Polynesian. They are confined to aborigines of the island of Taiwan, lying only 90 miles from the South China mainland. Taiwan's aborigines had the island largely to themselves until mainland Chinese began settling in large numbers within the last thousand years. Still more mainlanders arrived after 1945, especially after the Chinese Communists defeated the Chinese Nationalists in 1949, so that aborigines now constitute only 2 percent of Taiwan's population. The concentration of three out of the four Austronesian subfamilies on Taiwan suggests that, within the present Austronesian realm, Taiwan is the homeland where Austronesian languages have been spoken for the most millennia and have consequently had the longest time in which to diverge. All other Austronesian languages, from those on Madagascar to those on Easter Island, would then stem from a population expansion out of Taiwan.

原来,这另外3个语族都有重叠分布,与马来-波利尼西亚语族的分布相比,它们的分布范围全都很小。只有距华南大陆90英里的台湾岛的土著在使用这些语言[2]。台湾的土著占据了该岛的大部分地区,直到最近的几千年中大陆中国人才开始在岛上大批定居。1945年后,尤其是1949年中国共产党打败了中国国民党后,又有一批大陆人来到台湾,所以台湾土著现在只占台湾人口的2%。南岛语系的4个语族中有3个集中在台湾,这表明台湾就是今天各地南岛语的故乡,在过去几千年的大部分时间里,这些语言一直在台湾使用,因此有最长的时间来产生分化。这样看来,从马达加斯加到复活节岛,所有其他南岛语可能都起源于台湾向外的人口扩张。

WE CAN NOW turn to archaeological evidence. While the debris of ancient village sites does not include fossilized words along with bones and pottery, it does reveal movements of people and cultural artifacts that could be associated with languages. Like the rest of the world, most of the present Austronesian realm—Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and many Pacific islands—was originally occupied by hunter-gatherers lacking pottery, polished stone tools, domestic animals, and crops. (The sole exceptions to this generalization are the remote islands of Madagascar, eastern Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia, which were never reached by hunter-gatherers and remained empty of humans until the Austronesian expansion.) The first archaeological signs of something different within the Austronesian realm come from—Taiwan. Beginning around the fourth millennium B.C., polished stone tools and a distinctive decorated pottery style (so-called Ta-p'en-k'eng pottery) derived from earlier South China mainland pottery appeared on Taiwan and on the opposite coast of the South China mainland. Remains of rice and millet at later Taiwanese sites provide evidence of agriculture.

现在,我们可以转到考古证据方面来。虽然古代村落的遗址中没有随骨头和陶器一起出土的语言化石,但仍然显示了可以与语言联系起来的人的活动和文化产品。同世界上的其余地区一样,今天南岛语分布范围内的大部分地区——台湾、菲律宾、印度尼西亚和许多太平洋岛屿——原来都为狩猎采集族群所占据,他们没有陶器,没有打磨的石器,没有家畜,也没有作物。(这一推断的唯一例外是马达加斯加、美拉尼西亚东部、波利尼西亚和密克罗尼西亚这些偏远的岛屿,因为狩猎采集族群从来没有到达过这些地方,在南岛人扩张前一直是人迹不至。)在南岛语分布范围内,考古中发现最早的不同文化迹象的地方是——台湾。从公元前第四个一千年左右开始的打磨石器和源于华南大陆更早陶器的有图案装饰的不同陶器风格(所谓大坌坑陶器),在台湾和对面的华南大陆沿海地区出现。后来在台湾的一些遗址中出土的水稻和粟的残迹提供了关于农业的证据。

Ta-p'en-k'eng sites of Taiwan and the South China coast are full of fish bones and mollusk shells, as well as of stone net sinkers and adzes suitable for hollowing out a wooden canoe. Evidently, those first Neolithic occupants of Taiwan had watercraft adequate for deep-sea fishing and for regular sea traffic across Taiwan Strait, separating that island from the China coast. Thus, Taiwan Strait may have served as the training ground where mainland Chinese developed the open-water maritime skills that would permit them to expand over the Pacific.

台湾大坌坑遗址和华南沿海,不但有大量的石头网坠和适于刳木为舟的扁斧,而且也有大量的鱼骨和软体动物的壳。显然,台湾的这些新石器时代的最早居民已有了水运工具,足以胜任深海捕鱼,并可从事经常性的海上交通,渡过该岛与大陆之间的台湾海峡。因此,台湾海峡可能被用作航海训练场,大陆中国人在这里培养他们的航海技术,以便他们能够在太平洋上进行扩张。

One specific type of artifact linking Taiwan's Ta-p'en-k'eng culture to later Pacific island cultures is a bark beater, a stone implement used for pounding the fibrous bark of certain tree species into rope, nets, and clothing. Once Pacific peoples spread beyond the range of wool-yielding domestic animals and fiber plant crops and hence of woven clothing, they became dependent on pounded bark “cloth” for their clothing. Inhabitants of Rennell Island, a traditional Polynesian island that did not become Westernized until the 1930s, told me that Westernization yielded the wonderful side benefit that the island became quiet. No more sounds of bark beaters everywhere, pounding out bark cloth from dawn until after dusk every day!

一种把台湾大坌坑文化同后来的太平洋岛屿文化联系起来的特殊的人工制品是树皮舂捣器,这是一种石制工具,用来舂捣某些树的含纤维的树皮,以便制作绳索、鱼网和衣服。太平洋民族一旦到了没有产毛的家畜、没有纤维作物因而也就没有织造成的布的地方,他们穿衣就得依靠舂捣出来的树皮“布”了。伦纳尔岛是波利尼西亚的一个传统岛屿,直到20世纪30年代才开始西方化。这个岛上的居民对我说,西方化产生了一个附带的好处,就是岛上变得安静了。不再到处都是树皮舂捣器的声音了,不再每天从天亮一直舂捣到黄昏后了!

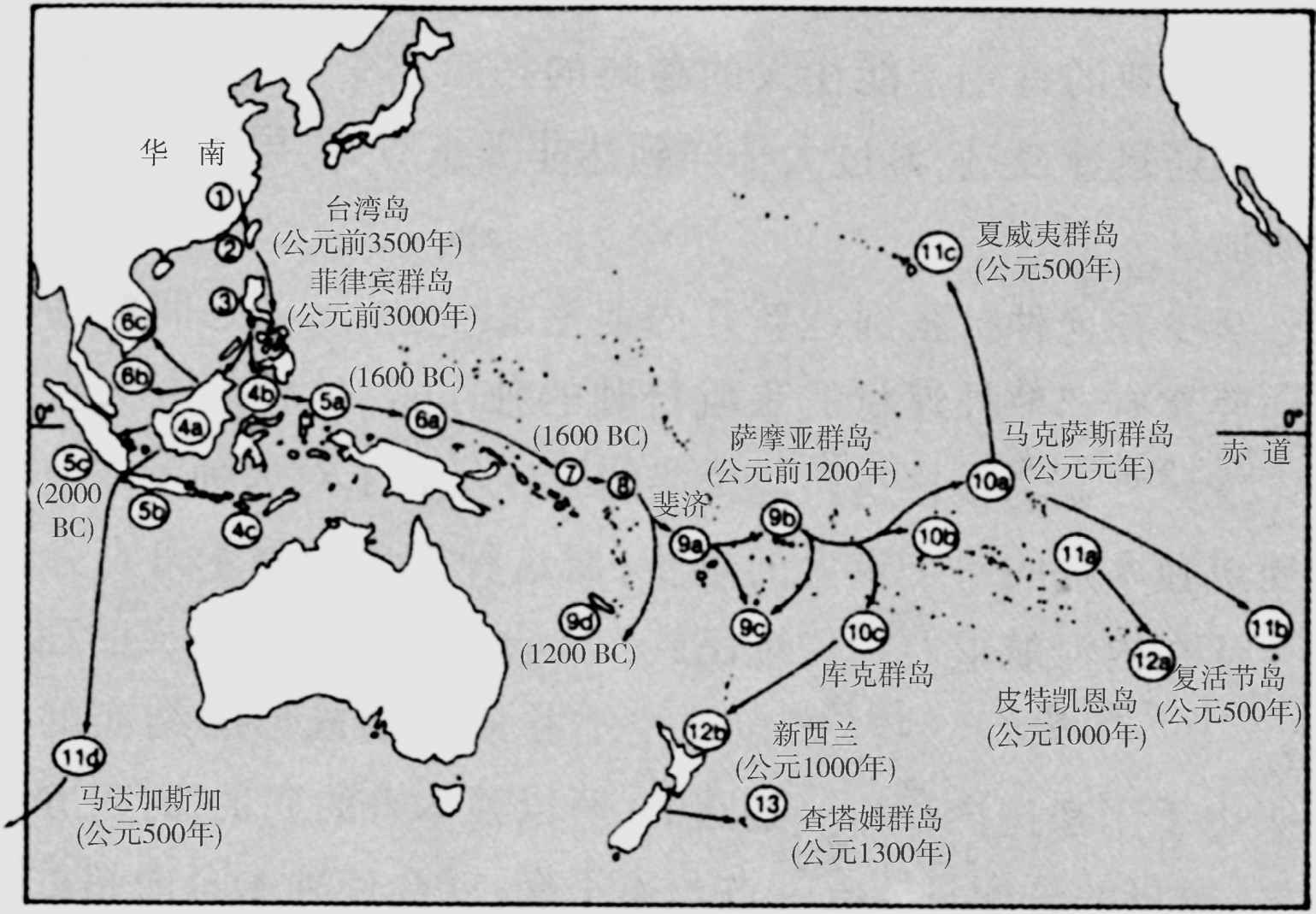

Within a millennium or so after the Ta-p'en-k'eng culture reached Taiwan, archaeological evidence shows that cultures obviously derived from it spread farther and farther from Taiwan to fill up the modern Austronesian realm (Figure 17.2). The evidence includes ground stone tools, pottery, bones of domestic pigs, and crop remains. For example, the decorated Ta-p'en-k'eng pottery on Taiwan gave way to undecorated plain or red pottery, which has also been found at sites in the Philippines and on the Indonesian islands of Celebes and Timor. This cultural “package” of pottery, stone tools, and domesticates appeared around 3000 B.C. in the Philippines, around 2500 B.C. on the Indonesian islands of Celebes and North Borneo and Timor, around 2000 B.C. on Java and Sumatra, and around 1600 B.C. in the New Guinea region. There, as we shall see, the expansion assumed a speedboat pace, as bearers of the cultural package raced eastward into the previously uninhabited Pacific Ocean beyond the Solomon Archipelago. The last phases of the expansion, during the millennium after A.D. 1, resulted in the colonization of every Polynesian and Micronesian island capable of supporting humans. Astonishingly, it also swept westward across the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa, resulting in the colonization of the island of Madagascar.

有考古证据表明,在大坌坑文化到达台湾后的1千年左右时间里,明显源自该文化的一些文化从台湾向外传播得越来越远,最后占据了现代南岛语的整个分布范围(图17.2)。这方面的证据包括磨制的石器、陶器、家猪的骨骼和作物的残迹。例如,台湾岛上有花纹的大坌坑陶器为没有花纹的素陶或红陶所代替,这种陶器在菲律宾和印度尼西亚的西里伯斯岛及帝汶岛上的一些遗址也有发现。这种包括陶器、石器和驯化动植物的“整体”文化在公元前3000年左右出现在菲律宾,在公元前2500年左右出现在印度尼西亚的西里伯斯岛、北婆罗洲和帝汶岛,在公元前2000年左右出现在爪哇和苏门答腊,在公元前1600年左右出现在新几内亚地区。我们将要看到,在那些地方的扩张呈现出快艇般的速度,人们携带着整个文化向东全速前进,进入了所罗门群岛以东过去没有人迹的太平洋岛屿。这一扩张的最后阶段发生在公元元年后的一千年中,导致了对波利尼西亚和密克罗尼西亚的每一个能住人的岛屿的拓殖。令人惊讶的是,这种扩张还迅速西进,渡过太平洋到达非洲东海岸,导致了对马达加斯加岛的拓殖。

Figure 17.2. The paths of the Austronesian expansion, with approximate dates when each region was reached.

图17.2 南岛人扩张路线及到达每一地区的大致年代。

| 2 | Taiwan Island(around 3500 B. C.) | 台湾岛(公元前3500年) |

| 4a | Borneo | 婆罗洲 |

| 4b | Celebes | 斯里伯斯岛 |

| 4c | Timor(around 2500 B. C.) | 帝汶岛(公元前2500年左右) |

| 5a | Halmahera(around 1600 B. C.) | 哈尔马赫拉岛(公元前1600年左右) |

| 5b | Java | 爪哇岛 |

| 5c | Sumatra(around 2000 B. C.) | 苏门答腊(公元前2000年左右) |

| 6a | Bismarck Archipelago(around 1600 B. C.) | 俾斯麦群岛(公元前1600年左右) |

| 6b | Malay Peninsula | 马来半岛 |

| 6c | Vietnam(around 1000 B. C.) | 越南(公元前1000年左右) |

| 7 | Solomon Archipelago(around 1600 B. C.) | 所罗门群岛(公元前1600年左右) |

| 8 | Santa Cruz | 圣克鲁斯群岛 |

| 9a | Fiji | 斐济 |

| 9c | Tonga | 汤加 |

| 9d | New Caledonia(around 1200 B. C.) | 新喀里多尼亚(公元前1200年左右) |

| lOb | Society Islands | 社会群岛 |

| lOc | Cook Islands | 库克群岛 |

| 11a | Tuamotu Archipelago(around A. D. 1) | 土阿莫土群岛(公元元年左右) |

| 11d | Madagascar | 马达加斯加(公元500年) |

| 13 | Chatham Islands | 查塔姆群岛(公元1300年) |

At least until the expansion reached coastal New Guinea, travel between islands was probably by double-outrigger sailing canoes, which are still widespread throughout Indonesia today. That boat design represented a major advance over the simple dugout canoes prevalent among traditional peoples living on inland waterways throughout the world. A dugout canoe is just what its name implies: a solid tree trunk “dug out” (that is, hollowed out), and its ends shaped, by an adze. Since the canoe is as round-bottomed as the trunk from which it was carved, the least imbalance in weight distribution tips the canoe toward the overweighted side. Whenever I've been paddled in dugouts up New Guinea rivers by New Guineans, I have spent much of the trip in terror: it seemed that every slight movement of mine risked capsizing the canoe and spilling out me and my binoculars to commune with crocodiles. New Guineans manage to look secure while paddling dugouts on calm lakes and rivers, but not even New Guineans can use a dugout in seas with modest waves. Hence some stabilizing device must have been essential not only for the Austronesian expansion through Indonesia but even for the initial colonization of Taiwan.

至少在这种扩张到达新几内亚沿海之前,各岛之间的往来可能要靠有双舷外浮材的张帆行驶的独木舟,这种船今天在整个印度尼西亚仍很普遍。这种船的设计代表了对那种刳木而成的简单独木舟的一个重大的进步,而这种简单的独木舟在全世界生活在内河航道上的传统民族中十分流行。刳木而成的独木舟,顾名思义,就是一段用扁斧挖空并使两端成形的结实的树干。由于用来掏挖的树干是圆的,所以独木舟的底部也是圆的,这样,重量的分配只要有一点点不平衡,就会使独木舟向超重的一边倾翻。每当我乘坐独木舟由新几内亚人划着沿着新几内亚的河流逆流而上时,一路上大部分时间里我都是提心吊胆,好像我只要稍微动一动,独木舟就会倾覆,把我和我的双筒望远镜翻落水中去与鳄鱼为伍。在风平浪静的江河湖泊里划独木舟,新几内亚人能够做到行所无事,但如果是在海上,即使风浪不太大,就连新几内亚人也不会去驾驶独木舟。因此,设计出某种稳定装置不但对南岛人在整个印度尼西亚进行扩张至关重要,而且甚至对台湾的最早开拓也是必不可少的。

The solution was to lash two smaller logs (“outriggers”) parallel to the hull and several feet from it, one on each side, connected to the hull by poles lashed perpendicular to the hull and outriggers. Whenever the hull starts to tip toward one side, the buoyancy of the outrigger on that side prevents the outrigger from being pushed under the water and hence makes it virtually impossible to capsize the vessel. The invention of the double-outrigger sailing canoe may have been the technological breakthrough that triggered the Austronesian expansion from the Chinese mainland.

解决办法是把两根较小的圆木(“浮材”)绑在船舷外侧,一边一根,距离船体几英尺远,用垂直地缚在船体和浮材上的支杆来连接。每当船体开始向一边倾侧时,那一边浮材的浮力使浮材不会被推入水下,因而实际上不可能使船倾覆。这种双舷外浮材张帆行驶独木舟的发明可能是促使南岛人从中国大陆向外扩张的技术突破。

TWO STRIKING COINCIDENCES between archaeological and linguistic evidence support the inference that the people bringing a Neolithic culture to Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia thousands of years ago spoke Austronesian languages and were ancestral to the Austronesian speakers still inhabiting those islands today. First, both types of evidence point unequivocally to the colonization of Taiwan as the first stage of the expansion from the South China coast, and to the colonization of the Philippines and Indonesia from Taiwan as the next stage. If the expansion had proceeded from tropical Southeast Asia's Malay Peninsula to the nearest Indonesian island of Sumatra, then to other Indonesian islands, and finally to the Philippines and Taiwan, we would find the deepest divisions (reflecting the greatest time depth) of the Austronesian language family among the modern languages of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra, and the languages of Taiwan and the Philippines would have differentiated only recently within a single subfamily. Instead, the deepest divisions are in Taiwan, and the languages of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra fall together in the same sub-sub-subfamily: a recent branch of the Western Malayo-Polynesian sub-subfamily, which is in turn a fairly recent branch of the Malayo-Polynesian subfamily. Those details of linguistic relationships agree perfectly with the archaeological evidence that the colonization of the Malay Peninsula was recent, and followed rather than preceded the colonization of Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

考古学证据和语言学证据之间两个引人注目的一致证实了这样的推断:几千年前把一种新石器文化带到台湾、菲律宾和印度尼西亚的民族说的是南岛语,并且是今天仍然居住在这些岛屿上的说南岛语的人的祖先。首先,这两种证据清楚地表明了向台湾的移民是从华南沿海向外扩张的第一阶段,而从台湾向菲律宾和印度尼西亚的移民则是这种扩张的第二阶段。如果这种扩张从热带东南亚的马来半岛开始,先到距离最近的印度尼西亚岛屿苏门答腊,然后到达印度尼西亚的其他岛屿,最后到达菲律宾和台湾,那么我们就会发现马来半岛和苏门答腊的现代语言中南岛语系的最深刻的变化(反映了最大的时间纵深),而台湾和菲律宾的语言可能只是在最近才在一个语族内发生分化。相反,最深刻的变化却发生在台湾,而马来半岛和苏门答腊的语言全都属于同一个亚语支:西马来-波利尼西亚语支最近出现的一个分支,而西马来-波利尼西亚语支又是波利尼西亚语族相当晚近出现的一个分支。语言关系的这些细节与考古证据完全一致,因为考古证据表明,向马来半岛移民是最近的事,它发生在向台湾、菲律宾和印度尼西亚移民之后,而不是发生在这之前。

The other coincidence between archaeological and linguistic evidence concerns the cultural baggage that ancient Austronesians used. Archaeology provides us with direct evidence of culture in the form of pottery, pig and fish bones, and so on. One might initially wonder how a linguist, studying only modern languages whose unwritten ancestral forms remain unknown, could ever figure out whether Austronesians living on Taiwan 6,000 years ago had pigs. The solution is to reconstruct the vocabularies of vanished ancient languages (so-called protolanguages) by comparing vocabularies of modern languages derived from them.

考古学证据与语言学证据之间的另一个一致之处,是古代南岛人所使用的整个文化内容。考古学为我们提供了以陶器、猪骨和鱼骨等为形式的直接文化证据。人们开始时可能会感到奇怪,一个只研究现代语言(这些语言的没有文字的祖代形式仍然无人知晓)的语言学家怎么会断定6000年前生活在台湾的人是否已经养猪。办法是比较来源于已经消失的古代语言(所谓原始母语)的现代语言词汇来重构古代语言的词汇。

For instance, the words meaning “sheep” in many languages of the Indo-European language family, distributed from Ireland to India, are quite similar: “avis,” “avis,” “ovis,” “oveja,” “ovtsa,” “owis,” and “oi” in Lithuanian, Sanskrit, Latin, Spanish, Russian, Greek, and Irish, respectively. (The English “sheep” is obviously from a different root, but English retains the original root in the word “ewe.”) Comparison of the sound shifts that the various modern Indo-European languages have undergone during their histories suggests that the original form was “owis” in the ancestral Indo-European language spoken around 6,000 years ago. That unwritten ancestral language is termed Proto-Indo-European.

例如,分布地区从爱尔兰到印度的印欧语系的许多语言中,意思为“羊”的词都十分相似:在立陶宛语、梵语、拉丁语、西班牙语、俄语、希腊语和爱尔兰语中分别为“avis”、“avis”、“ovis”、“oveja”、“ovtsa”、“owis”和“oi”。(英语的“sheep”显然来源不同,但英语在“ewe”〔母羊〕这个词中仍保留了原来的词根。)对各种现代印欧语在历史过程中经历的语言演变所进行的比较表明,在大约6000年前的祖代印欧语中,这个词的原来形式是“owis”。这种没有文字的祖代语言称之为原始印欧语。

Evidently, Proto-Indo-Europeans 6,000 years ago had sheep, in agreement with archaeological evidence. Nearly 2,000 other words of their vocabulary can similarly be reconstructed, including words for “goat,” “horse,” “wheel,” “brother,” and “eye.” But no Proto-Indo-European word can be reconstructed for “gun,” which uses different roots in different modern Indo-European languages: “gun” in English, “fusil” in French, “ruzhyo” in Russian, and so on. That shouldn't surprise us: people 6,000 years ago couldn't possibly have had a word for guns, which were invented only within the past 1,000 years. Since there was thus no inherited shared root meaning “gun,” each Indo-European language had to invent or borrow its own word when guns were finally invented.

显然,6000年前的原始印欧人已经饲养羊,这是与考古证据一致的。他们的词汇中另外有将近2000个词同样可以予以重构,其中包括表示“山羊”、“马”、“轮子”、“兄弟”和“眼睛”这些词。但表示“gun”(枪炮)的词却无法从任何原始印欧语的词重构出来,这个词在不同的现代印欧语中用的是不同的词根:在英语中是“gun”,在法语中是“fusil”,在俄语中是“ruzhyo”,(Ружьё)等等。这一点不应使我们感到惊奇:6000年前的人不可能有表示枪炮的词,因为枪炮只是过去1000年内发明出来的武器。由于没有继承下来的表示“枪炮”这个意思的共同词根,所以在枪炮最后发明出来时,每一种印欧语都得创造出自己的词来或者从别处借用。

Proceeding in the same way, we can compare modern Taiwanese, Philippine, Indonesian, and Polynesian languages to reconstruct a Proto-Austronesian language spoken in the distant past. To no one's surprise, that reconstructed Proto-Austronesian language had words with meanings such as “two,” “bird,” “ear,” and “head louse”: of course, Proto-Austronesians could count to 2, knew of birds, and had ears and lice. More interestingly, the reconstructed language had words for “pig,” “dog,” and “rice,” which must therefore have been part of Proto-Austronesian culture. The reconstructed language is full of words indicating a maritime economy, such as “outrigger canoe,” “sail,” “giant clam,” “octopus,” “fish trap,” and “sea turtle.” This linguistic evidence regarding the culture of Proto-Austronesians, wherever and whenever they lived, agrees well with the archaeological evidence regarding the pottery-making, sea-oriented, food-producing people living on Taiwan around 6,000 years ago.

我们可以用同样的办法,把现代的台湾语、菲律宾语、印度尼西亚语和波利尼西亚语加以比较,从而重构出在远古所使用的一种原始南岛语来。谁也不会感到惊奇的是,这种重构出来的原始南岛语有这样一些意思的词如“二”、“鸟”、“耳朵”和“头虱”;当然,原始的南岛人能够数到2,知道鸟,有耳朵和虱子。更有意思的是,这种重构出来的语言中有表示“猪”、“狗”和“米”这些意思的词,因此这些东西想必是原始南岛文化的一部分。这种重构出来的语言中有大量表示海洋经济的词,如“带舷外浮材的独木舟”、“帆”、“大蛤”、“章鱼”、“渔栅”和“海龟”。不管原始的南岛人生活在什么地方和什么时候,关于他们的文化的语言学证据与关于大约6000年前生活在台湾的能够制陶、面向海洋、从事粮食生产的民族的考古学证据非常吻合。

The same procedure can be applied to reconstruct Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, the ancestral language spoken by Austronesians after emigrating from Taiwan. Proto-Malayo-Polynesian contains words for many tropical crops like taro, breadfruit, bananas, yams, and coconuts, for which no word can be reconstructed in Proto-Austronesian. Thus, the linguistic evidence suggests that many tropical crops were added to the Austronesian repertoire after the emigration from Taiwan. This conclusion agrees with archaeological evidence: as colonizing farmers spread southward from Taiwan (lying about 23 degrees north of the equator) toward the equatorial tropics, they came to depend increasingly on tropical root and tree crops, which they proceeded to carry with them out into the tropical Pacific.

同样的方法也可用来重构原始的马来-波利尼西亚语,这是南岛人从台湾向外移民后所使用的祖代语言。原始的马来-波利尼西亚语中有一些用来表示热带作物的词,如芋艿、面包果、香蕉、薯蓣和椰子,在原始的南岛语中,无法重构出任何表示这些作物的词。因此,这个语言学上的证据表明,南岛语中许多热带作物的名字是在南岛人从台湾向外移民后才有的。这个结论是与考古学上的证据相一致的:随着农民移民从台湾(位于赤道以北23度附近)南下,向赤道热带地区扩散,他们开始越来越依赖热带的根用作物和树生作物,接着他们又把这些作物带进了热带太平洋地区。

How could those Austronesian-speaking farmers from South China via Taiwan replace the original hunter-gatherer population of the Philippines and western Indonesia so completely that little genetic and no linguistic evidence of that original population survived? The reasons resemble the reasons why Europeans replaced or exterminated Native Australians within the last two centuries, and why South Chinese replaced the original tropical Southeast Asians earlier: the farmers' much denser populations, superior tools and weapons, more developed watercraft and maritime skills, and epidemic diseases to which the farmers but not the hunter-gatherers had some resistance. On the Asian mainland Austronesian-speaking farmers were able similarly to replace some of the former hunter-gatherers of the Malay Peninsula, because Austronesians colonized the peninsula from the south and east (from the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo) around the same time that Austroasiatic-speaking farmers were colonizing the peninsula from the north (from Thailand). Other Austronesians managed to establish themselves in parts of southern Vietnam and Cambodia to become the ancestors of the modern Chamic minority of those countries.

那些从华南经由台湾南下的说南岛语的农民怎么会这样全面地更替了菲律宾和印度尼西亚西部的狩猎采集人口,以致那原有的人口很少留下什么遗传学的证据和根本没有留下任何语言学的证据?其原因与欧洲在过去不到两个世纪的时间内更替或消灭澳大利亚土著的原因相同,也与华南人在这以前更替了热带东南亚人的原因相同:即农民的稠密得多的人口、优良的工具和武器、更发达的水运工具和航海技术以及只有农民而不是狩猎采集族群才对之有某种抵抗力的流行疾病。在亚洲大陆,说南岛语的农民同样能够更替马来半岛上以前的狩猎采集族群,因为他们从南面和东面(从印度尼西亚的岛屿苏门答腊和婆罗洲)向该半岛移民,与说南亚语的农民从北面(从泰国)向该半岛移民差不多同时。其他一些说南岛语的人终于在越南南部和柬埔寨的一些地方立定了脚根,成为这两个国家中说占语的现代少数民族的祖先。

However, Austronesian farmers could spread no farther into the Southeast Asian mainland, because Austroasiatic and Tai-Kadai farmers had already replaced the former hunter-gatherers there, and because Austronesian farmers had no advantage over Austroasiatic and Tai-Kadai farmers. Although we infer that Austronesian speakers originated from coastal South China, Austronesian languages today are not spoken anywhere in mainland China, possibly because they were among the hundreds of former Chinese languages eliminated by the southward expansion of Sino-Tibetan speakers. But the language families closest to Austronesian are thought to be Tai-Kadai, Austroasiatic, and Miao-Yao. Thus, while Austronesian languages in China may not have survived the onslaught of Chinese dynasties, some of their sister and cousin languages did.

然而,说南岛语的农民未能再向前进入东南亚大陆,因为说南亚语和加岱语的农民已经更替了那里原有的狩猎采集族群,同时也因为说南岛语的农民并不拥有对说南亚语和傣-加岱语的农民的任何优势。虽然根据我们的推断,说南岛语的人来自华南沿海地区,但在今天的大陆中国已没有人说南岛语了,这可能是因为它们在说汉藏语的人向南扩张时同其他几百种原有的中国语言一起被消灭了。但与南岛语最接近的语族据认为是傣-加岱语、南亚语和苗瑶语。因此,虽然中国的南岛语可能没有逃过被中国王朝攻击的命运,但它们的一些亲属语言却逃过了。

WE HAVE NOW followed the initial stages of the Austronesian expansion for 2,500 miles from the South China coast, through Taiwan and the Philippines, to western and central Indonesia. In the course of that expansion, Austronesians came to occupy all habitable areas of those islands, from the seacoast to the interior, and from the lowlands to the mountains. By 1500 B.C. their familiar archaeological hallmarks, including pig bones and plain red-slipped pottery, show that they had reached the eastern Indonesian island of Halmahera, less than 200 miles from the western end of the big mountainous island of New Guinea. Did they proceed to overrun that island, just as they had already overrun the big mountainous islands of Celebes, Borneo, Java, and Sumatra?

至此,我们已经跟随说南岛语的人走过了他们初期阶段的扩张路线,从华南沿海经过台湾和菲律宾到达印度尼西亚的西部和中部,行程2500英里。在这扩张过程中,这些说南岛语的人从海岸到内陆,从低地到山区,逐步占据了这些岛上所有适于居住的地区。他们的为人所熟知的不迟于公元前1500年的考古标志——包括猪骨和素面红纹陶器——表明,他们已经到达了印度尼西亚东部的哈尔马赫拉岛,距离新几内亚这个多山的大岛的东端不到200英里。他们是否像已经占领斯里伯斯、婆罗洲、爪哇和苏门答腊这些多山的大岛那样,去着手占领新几内亚呢?

They did not, as a glance at the faces of most modern New Guineans makes obvious, and as detailed studies of New Guinean genes confirm. My friend Wiwor and all other New Guinea highlanders differ obviously from Indonesians, Filipinos, and South Chinese in their dark skins, tightly coiled hair, and face shapes. Most lowlanders from New Guinea's interior and south coast resemble the highlanders except that they tend to be taller. Geneticists have failed to find characteristic Austronesian gene markers in blood samples from New Guinea highlanders.

他们没有那样做,看一看大多数现代新几内亚人的脸就会清楚地知道,对新几内亚人的遗传所进行的详细研究也证实了这一点。我的朋友维沃尔和其他所有新几内亚高原人的黑皮肤、浓密的鬈发和脸型,与印度尼西亚人、菲律宾人和华南人是明显不同的。新几内亚内陆和南部沿海的低地人与高原人相似,只是身材一般较高。遗传学家没有能从新几内亚高原人的血样中发现南岛人特有的遗传标志。

But peoples of New Guinea's north and east coasts, and of the Bismarck and Solomon Archipelagoes north and east of New Guinea, present a more complex picture. In appearance, they are variably intermediate between highlanders like Wiwor and Indonesians like Achmad, though on the average considerably closer to Wiwor. For instance, my friend Sauakari from the north coast has wavy hair intermediate between Achmad's straight hair and Wiwor's coiled hair, and skin somewhat paler than Wiwor's, though considerably darker than Achmad's. Genetically, the Bismarck and Solomon islanders and north coastal New Guineans are about 15 percent Austronesian and 85 percent like New Guinea highlanders. Hence Austronesians evidently reached the New Guinea region but failed completely to penetrate the island's interior and were genetically diluted by New Guinea's previous residents on the north coast and islands.

但对新几内亚北部和东部沿海民族和新几内亚北面和东面的俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛的民族来说,情况就比较复杂。从外表来看,他们或多或少地介于像维沃尔这样的高原人和像阿什马德这样的印度尼西亚人之间,不过一般都大大接近维沃尔。例如,我的朋友索阿卡里来自北部沿海地区,他的波浪形头发介于阿什马德的直发和维沃尔的鬈发之间,他的肤色比维沃尔的肤色多少要浅一些,却又比阿什马德的肤色深得多。从遗传来看,俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛上的居民有大约15%的说南岛语族群的成分,而85%像新几内亚高原地区的人。因此,南岛人显然到过新几内亚地区,但未能完全深入该岛腹地,所以在遗传上被新几内亚北部海岸和岛屿上的原先居民所削弱了。

Modern languages tell essentially the same story but add detail. In Chapter 15 I explained that most New Guinea languages, termed Papuan languages, are unrelated to any language families elsewhere in the world. Without exception, every language spoken in the New Guinea mountains, the whole of southwestern and south-central lowland New Guinea, including the coast, and the interior of northern New Guinea is a Papuan language. But Austronesian languages are spoken in a narrow strip immediately on the north and southeast coasts. Most languages of the Bismarck and Solomon islands are Austronesian: Papuan languages are spoken only in isolated pockets on a few islands.

现代语言基本上说的是同一个故事,不过更详细罢了。我在第十五章说过,大多数新几内亚语言叫做巴布亚诸语言,它们同世界上其他地方的任何语系都没有亲缘关系。在新几内亚山区、新几内亚西南部和中南部整个低地地区(包括新几内亚海岸地区和北部内陆地区)所说的每一种语言,毫无例外都是某一种巴布亚语。但某些南岛语言只在北部和东南部附近的一片狭长地带使用。俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛上的大多数语言是南岛语言,某些巴布亚语言只在几个岛上的一些小块孤立地区使用。

Austronesian languages spoken in the Bismarcks and Solomons and north coastal New Guinea are related, as a separate sub-sub-subfamily termed Oceanic, to the sub-sub-subfamily of languages spoken on Halmahera and the west end of New Guinea. That linguistic relationship confirms, as one would expect from a map, that Austronesian speakers of the New Guinea region arrived by way of Halmahera. Details of Austronesian and Papuan languages and their distributions in North New Guinea testify to long contact between the Austronesian invaders and the Papuan-speaking residents. Both the Austronesian and the Papuan languages of the region show massive influences of each other's vocabularies and grammars, making it difficult to decide whether certain languages are basically Austronesian languages influenced by Papuan ones or the reverse. As one travels from village to village along the north coast or its fringing islands, one passes from a village with an Austronesian language to a village with a Papuan language and then to another Austronesian-speaking village, without any genetic discontinuity at the linguistic boundaries.

在俾斯麦群岛、所罗门群岛和新几内亚北部沿海所使用的南岛语言是一个叫做大洋洲语言的亚语支,它们同哈尔马赫拉岛和新几内亚西端所使用的语言的亚语支有着亲缘关系。人们在看地图时可能会想到,这种语言学上的关系证实了新几内亚地区说南岛语的人是取道哈尔马赫拉岛到达新几内亚的。南岛语和巴布亚语的一些细节和它们在新几内亚北部的分布情况表明,说南岛语的入侵者与说巴布亚语的本地居民有过长期的交往。这个地区的南岛语和巴布亚语显示了对彼此的词汇和语法的巨大影响,使人难以确定某些语言基本上是受到巴布亚语言影响的南岛语还是受到南岛语言影响的巴布亚语言。如果你在新几内亚北部沿海或海岸外的岛屿上旅行,走过了一个又一个村子,你会发现一个村子讲的是南岛语,下一个村子讲的是巴布亚语,再下一个村子讲的又是南岛语,但在语言分界线上却没有发生任何遗传中断。

All this suggests that descendants of Austronesian invaders and of original New Guineans have been trading, intermarrying, and acquiring each other's genes and languages for several thousand years on the North New Guinea coast and its islands. That long contact transferred Austronesian languages more effectively than Austronesian genes, with the result that most Bismarck and Solomon islanders now speak Austronesian languages, even though their appearance and most of their genes are still Papuan. But neither the genes nor the languages of the Austronesians penetrated New Guinea's interior. The outcome of their invasion of New Guinea was thus very different from the outcome of their invasion of Borneo, Celebes, and other big Indonesian islands, where their steamroller eliminated almost all traces of the previous inhabitants' genes and languages. To understand what happened in New Guinea, let us now turn to the evidence from archaeology.

所有这一切表明,说南岛语的入侵者的后代和原来新几内亚人的后代,几千年来一直在新几内亚北部沿海地区及其岛屿上进行贸易、通婚并获得了彼此的基因与语言。这种长期的接触对转移南岛语言效果较大,而对转移南岛人的基因则效果较小,其结果是俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛的岛民现在说的是南岛语,而他们的外貌和大多数基因却仍然是巴布亚人的。但南岛人的基因和语言都没有能深入新几内亚的腹地。这样,他们入侵新几内亚的结果就和他们入侵婆罗洲、西里伯斯和其他印度尼西亚大岛的结果大不相同,因为他们在印度尼西亚的这些岛屿以不可阻挡之势把原先居民的基因和语言消灭殆尽。为了弄清楚在新几内亚发生的事情,让我们现在转到考古证据上来。

AROUND 1600 B.C., almost simultaneously with their appearance on Halmahera, the familiar archaeological hallmarks of the Austronesian expansion—pigs, chickens, dogs, red-slipped pottery, and adzes of ground stone and of giant clamshells—appear in the New Guinea region. But two features distinguish the Austronesians' arrival there from their earlier arrival in the Philippines and Indonesia.

公元前1600年左右,人们所熟知的南岛人扩张的考古标志——猪、鸡、狗、红纹陶、打磨石扁斧和大蛤壳——在哈尔马赫拉岛出现,几乎与此同时,这些东西也在新几内亚地区出现了。但南岛人到达新几内亚与他们在这之前到达菲律宾和印度尼西亚有两个不同的特点。

The first feature consists of pottery designs, which are aesthetic features of no economic significance but which do let archaeologists immediately recognize an early Austronesian site. Whereas most early Austronesian pottery in the Philippines and Indonesia was undecorated, pottery in the New Guinea region was finely decorated with geometric designs arranged in horizontal bands. In other respects the pottery preserved the red slip and the vessel forms characteristic of earlier Austronesian pottery in Indonesia. Evidently, Austronesian settlers in the New Guinea region got the idea of “tattooing” their pots, perhaps inspired by geometric designs that they had already been using on their bark cloth and body tattoos. This style is termed Lapita pottery, after an archaeological site named Lapita, where it was described.

第一个特点是陶器的纹饰。陶器的纹饰具有审美特点而不具有任何经济意义,但却使考古学家立即认出某个早期的南岛人遗址。虽然菲律宾和印度尼西亚的南岛人的大多数早期陶器都没有纹饰,但新几内亚地区的陶器却有着水平带状几何图形的精美纹饰。在其他方面,这种陶器还保留了印度尼西亚的南岛人的早期陶器所特有的红色泥釉和器皿形制。显然,新几内亚地区南岛人移民想到了给他们的壶罐“文身”,这也许是受到他们已经用在树皮布和文身花纹上的几何图案的启发。这个风格的陶器叫做拉皮塔陶器,这是以它的绘制之处名叫拉皮塔的考古遗址命名的。

The much more significant distinguishing feature of early Austronesian sites in the New Guinea region is their distribution. In contrast to those in the Philippines and Indonesia, where even the earliest known Austronesian sites are on big islands like Luzon and Borneo and Celebes, sites with Lapita pottery in the New Guinea region are virtually confined to small islets fringing remote larger islands. To date, Lapita pottery has been found at only one site (Aitape) on the north coast of New Guinea itself, and at a couple of sites in the Solomons. Most Lapita sites of the New Guinea region are in the Bismarcks, on islets off the coast of the larger Bismarck islands, occasionally on the coasts of the larger islands themselves. Since (as we shall see) the makers of Lapita pottery were capable of sailing thousands of miles, their failure to transfer their villages a few miles to the large Bismarck islands, or a few dozen miles to New Guinea, was certainly not due to inability to get there.

新几内亚地区南岛人早期遗址的重要得多的与众不同的特点是它们的分布。在菲律宾和印度尼西亚,甚至已知最早的南岛人遗址都是在一些大岛上,如吕宋、婆罗洲和西里伯斯,但新几内亚地区的拉皮塔陶器遗址则不同,它们几乎都是在偏远大岛周边的一些小岛上。迄今为止,发现拉皮塔陶器的只有新几内亚北部海岸上的一处遗址(艾泰普)和所罗门群岛上的两三处遗址。新几内亚地区发现拉皮塔陶器的大多数遗址是在俾斯麦群岛,在俾斯麦群岛中较大岛屿海岸外的小岛上,偶尔也在这些较大岛屿本身的海岸上。既然(我们将要看到)这些制作拉皮塔陶器的人能够航行几千英里之遥,但他们却未能把他们的村庄搬到几英里外的俾斯麦群岛中的大岛上去,也未能搬到几十英里外的新几内亚去,这肯定不是由于他们没有能力到达那里。

The basis of Lapita subsistence can be reconstructed from the garbage excavated by archaeologists at Lapita sites. Lapita people depended heavily on seafood, including fish, porpoises, sea turtles, sharks, and shellfish. They had pigs, chickens, and dogs and ate the nuts of many trees (including coconuts). While they probably also ate the usual Austronesian root crops, such as taro and yams, evidence of those crops is hard to obtain, because hard nut shells are much more likely than soft roots to persist for thousands of years in garbage heaps.

拉皮塔人赖以生存的基础可以根据考古学家们在拉皮塔遗址出土的那些垃圾重构出来。拉皮塔人生活的主要依靠是海产,其中包括鱼、海豚、海龟、鲨鱼和有壳水生动物。他们饲养猪、鸡和狗,吃许多树上的坚果(包括椰子)。虽然他们可能也吃南岛人常吃的根用作物如芋艿和薯蓣,但很难找到关于这些作物的证据,因为坚硬的坚果壳在垃圾堆里保存几千年的可能性要比软柔的根茎大得多。

Naturally, it is impossible to prove directly that the people who made Lapita pots spoke an Austronesian language. However, two facts make this inference virtually certain. First, except for the decorations on the pots, the pots themselves and their associated cultural paraphernalia are similar to the cultural remains found at Indonesian and Philippine sites ancestral to modern Austronesian-speaking societies. Second, Lapita pottery also appears on remote Pacific islands with no previous human inhabitants, with no evidence of a major second wave of settlement subsequent to that bringing Lapita pots, and where the modern inhabitants speak an Austronesian language (more of this below). Hence Lapita pottery may be safely assumed to mark Austronesians' arrival in the New Guinea region.

当然,要想直接证明制造拉皮塔陶器的人说的是某种南岛语,这是不可能的。然而,有两个事实使得这一推断几乎确定无疑。首先,除了这些陶器上的纹饰外,这些陶器本身以及与其相联系的文化器材,同印度尼西亚和菲律宾现代的说南岛语社会的古代遗址中发现的文化遗存有类似之处。其次,拉皮塔陶器还出现在以前人迹不到的遥远的太平洋岛屿上,但没有任何证据表明,在那次带来拉皮塔陶器的移民浪潮后接着又出现过第二次重大的移民浪潮,而这些岛上的现代居民说的又是一种南岛语言(详见下文)。因此,可以有把握地假定,拉皮塔陶器是南岛人到达新几内亚的标志。

What were those Austronesian pot makers doing on islets adjacent to bigger islands? They were probably living in the same way as modern pot makers lived until recently on islets in the New Guinea region. In 1972 I visited such a village on Malai Islet, in the Siassi island group, off the medium-sized island of Umboi, off the larger Bismarck island of New Britain. When I stepped ashore on Malai in search of birds, knowing nothing about the people there, I was astonished by the sight that greeted me. Instead of the usual small village of low huts, surrounded by large gardens sufficient to feed the village, and with a few canoes drawn up on the beach, most of the area of Malai was occupied by two-story wooden houses side by side, leaving no ground available for gardens—the New Guinea equivalent of downtown Manhattan. On the beach were rows of big canoes. It turned out that Malai islanders, besides being fishermen, were also specialized potters, carvers, and traders, who lived by making beautifully decorated pots and wooden bowls, transporting them in their canoes to larger islands and exchanging their wares for pigs, dogs, vegetables, and other necessities. Even the timber for Malai canoes was obtained by trade from villagers on nearby Umboi Island, since Malai does not have trees big enough to be fashioned into canoes.

那些说南岛语的制造陶器的人在大岛附近的小岛上干些什么呢?他们可能和直到最近还生活在新几内亚地区的一些小岛上的制陶人过着同样的生活。1972年,我访问了锡亚西岛群中的马莱岛上的一个这样的村庄。锡亚西岛群在中等大小的翁博伊岛的外面,而翁博伊岛又在新不列颠群岛中较大的俾斯麦岛的外面。当我在马莱岛上岸找鸟时,我对那里的人一无所知,所以我看到的情景使我大吃一惊。在这类地方人们通常看到的是有低矮简陋的小屋的村庄,四周围着足以供应全村的园圃,沙滩上系着几条独木舟。但马莱岛的情况却不是这样,那里的大部分地区都建有一排排木屋,没有留下任何可以用作园圃的隙地——简直就是新几内亚版的曼哈顿闹市区。沙滩上有成排的大独木舟。原来马莱岛的居民除了会捕鱼外,还是专业的陶工、雕刻工和商人。他们的生计靠制造精美的有纹饰的陶器和木碗,用独木舟把它们运往一些大的岛屿,用他们的物品换来猪、狗、蔬菜和其他生活必需品。甚至马莱岛的居民用来造独木舟的木材也是从附近的翁博伊岛上的村民那里交换来的,因为马莱岛没有可以用来做成独木舟的大树。

In the days before European shipping, trade between islands in the New Guinea region was monopolized by such specialized groups of canoe-building potters, skilled in sailing without navigational instruments, and living on offshore islets or occasionally in mainland coastal villages. By the time I reached Malai in 1972, those indigenous trade networks had collapsed or contracted, partly because of competition from European motor vessels and aluminum pots, partly because the Australian colonial government forbade long-distance canoe voyaging after some accidents in which traders were drowned. I would guess that the Lapita potters were the inter-island traders of the New Guinea region in the centuries after 1600 B.C.

在欧洲航运业出现以前的日子里,新几内亚各岛屿之间的贸易是由这些制造独木舟的陶工集团垄断的,他们没有航海仪器但却精于航行,他们生活在近海的小岛上,有时也生活在大陆沿海的村庄里。到1972年我到达马莱岛的时候,当地的这些贸易网或者已经瓦解,或者已经萎缩,这一部分是由于欧洲内燃机船和铝制壶罐的竞争,一部分是由于澳大利亚殖民政府在几次淹死商人的事故后禁止独木舟长途航行。我可以推测,在公元前1600年后的许多世纪中,拉皮塔的陶工就是新几内亚地区进行岛际贸易的商人。

The spread of Austronesian languages to the north coast of New Guinea itself, and over even the largest Bismarck and Solomon islands, must have occurred mostly after Lapita times, since Lapita sites themselves were concentrated on Bismarck islets. Not until around A.D. I did pottery derived from the Lapita style appear on the south side of New Guinea's southeast peninsula. When Europeans began exploring New Guinea in the late 19th century, all the remainder of New Guinea's south coast still supported populations only of Papuan-language speakers, even though Austronesian-speaking populations were established not only on the southeastern peninsula but also on the Aru and Kei Islands (lying 70–80 miles off western New Guinea's south coast). Austronesians thus had thousands of years in which to colonize New Guinea's interior and its southern coast from nearby bases, but they never did so. Even their colonization of North New Guinea's coastal fringe was more linguistic than genetic: all northern coastal peoples remained predominantly New Guineans in their genes. At most, some of them merely adopted Austronesian languages, possibly in order to communicate with the long-distance traders who linked societies.

南岛语向新几内亚北部海岸传播,甚至在最大的俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛上传播,必定多半是在拉皮塔时代以后发生的,因为拉皮塔遗址本身就是集中在俾斯麦群岛中的一些小岛上的。直到公元元年左右,具有拉皮塔风格的陶器才出现在新几内亚东南半岛的南侧。当欧洲人在19世纪晚些时候开始对新几内亚进行实地考察时,新几内亚南部沿海的所有其余地区仍然只生活着说巴布亚语的人,虽然说南岛语的人不但在东南部的半岛而且也在阿鲁岛和凯岛(距新几内亚南海岸西部70—80英里处)立定了脚根。因此,说南岛语的人可以有几千年的时间从附近的基地向新几内亚内陆和南部海岸地区移民,但他们没有这样做。甚至他们对新几内亚北部海岸边缘地区的移民,与其说是遗传上的,不如说是语言上的;所有北部海岸地区的人从遗传来看绝大多数仍然是新几内亚人。他们中的一些人最多只是采用了南岛语言,而这可能是为了与那些实现社会与社会沟通的长途贩运的商人进行交际的目的。

THUS, THE OUTCOME of the Austronesian expansion in the New Guinea region was opposite to that in Indonesia and the Philippines. In the latter region the indigenous population disappeared—presumably driven off, killed, infected, or assimilated by the invaders. In the former region the indigenous population mostly kept the invaders out. The invaders (the Austronesians) were the same in both cases, and the indigenous populations may also have been genetically similar to each other, if the original Indonesian population supplanted by Austronesians really was related to New Guineans, as I suggested earlier. Why the opposite outcomes?

因此,南岛人在新几内亚地区扩张的结果与在印度尼西亚和菲律宾扩张的结果全然不同。在印度尼西亚和菲律宾,当地的人口消失了——大概是被这些入侵者赶走、杀死、用传染病害死或甚至同化了。而在新几内亚,当地的人口多半把这些入侵者挡在外面。在这两种情况下,入侵者(南岛人)都是一样的,而当地的居民从遗传来看也可能彼此相似,如果就像我前面提到的那样,被南岛人所取代的原有的印度尼西亚居民与新几内亚人真的有亲戚关系的话。那么,为什么还会有这种全然不同的结果呢?

The answer becomes obvious when one considers the differing cultural circumstances of Indonesia's and New Guinea's indigenous populations. Before Austronesians arrived, most of Indonesia was thinly occupied by hunter-gatherers lacking even polished stone tools. In contrast, food production had already been established for thousands of years in the New Guinea highlands, and probably in the New Guinea lowlands and in the Bismarcks and Solomons as well. The New Guinea highlands supported some of the densest populations of Stone Age people anywhere in the modern world.

如果考虑一下印度尼西亚和新几内亚本地人的不同的文化环境,答案就变得显而易见了。在南岛人到来之前,印度尼西亚的大部分地区只有稀少的甚至连打磨石器都没有的狩猎采集族群。相比之下,在新几内亚高原地区,可能还有新几内亚低地地区以及俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛,粮食生产的确立已有几千年之久。新几内亚高原地区养活了在现代世界上任何地方都算得上最稠密的石器时代的人口。

Austronesians enjoyed few advantages in competing with those established New Guinean populations. Some of the crops on which Austronesians subsisted, such as taro, yams, and bananas, had probably already been independently domesticated in New Guinea before Austronesians arrived. The New Guineans readily integrated Austronesian chickens, dogs, and especially pigs into their food-producing economies. New Guineans already had polished stone tools. They were at least as resistant to tropical diseases as were Austronesians, because they carried the same five types of genetic protections against malaria as did Austronesians, and some or all of those genes evolved independently in New Guinea. New Guineans were already accomplished seafarers, although not as accomplished as the makers of Lapita pottery. Tens of thousands of years before the arrival of Austronesians, New Guineans had colonized the Bismarck and Solomon Archipelagoes, and a trade in obsidian (a volcanic stone suitable for making sharp tools) was thriving in the Bismarcks at least 18,000 years before the Austronesians arrived. New Guineans even seem to have expanded recently westward against the Austronesian tide, into eastern Indonesia, where languages spoken on the islands of North Halmahera and of Timor are typical Papuan languages related to some languages of western New Guinea.

南岛人在与那些已经扎下根来的新几内亚人的竞争中几乎没有任何优势。南岛人赖以生存的一些作物,如芋艿、薯蓣和香蕉,可能是在南岛人到来之前就已在新几内亚独立驯化出来了。新几内亚人很快就把南岛人的鸡、狗、尤其是猪吸收进他们的粮食生产经济中来。新几内亚人已经有了打磨的石器。他们对一些热带疾病的抵抗力至少不比南岛人差,因为他们同南岛人一样,也有同样的5种预防疟疾的基因,而这些基因有些或全部都是在新几内亚独立演化出来的。新几内亚人早已是熟练的航海者,虽然就造诣来说还赶不上制造拉皮塔陶器。在南岛人到来之前的几万年中,新几内亚人便已向俾斯麦群岛和所罗门群岛移民,而至少在南岛人到来之前的1800年中,黑曜石(一种适于制作锋锐工具的火山石)贸易便已兴旺发达起来。新几内亚人甚至好像在不久前逆南岛人的移民浪潮而向西扩张,进入印度尼西亚东部,那里的哈尔马赫拉岛北部和帝汶岛上所说的语言是典型的巴布亚语,与新几内亚西部的某些语言有着亲属关系。

In short, the variable outcomes of the Austronesian expansion strikingly illustrate the role of food production in human population movements. Austronesian food-producers migrated into two regions (New Guinea and Indonesia) occupied by resident peoples who were probably related to each other. The residents of Indonesia were still hunter-gatherers, while the residents of New Guinea were already food producers and had developed many of the concomitants of food production (dense populations, disease resistance, more advanced technology, and so on). As a result, while the Austronesian expansion swept away the original Indonesians, it failed to make much headway in the New Guinea region, just as it also failed to make headway against Austroasiatic and Tai-Kadai food producers in tropical Southeast Asia.

总之,南岛人扩张的不同结果引人注目地证明了粮食生产在人口流动中的作用。说南岛语的粮食生产者迁入了两个由可能有亲属关系的原住民占有的地区(新几内亚和印度尼西亚)。印度尼西亚的居民仍然是狩猎采集族群,而新几内亚的居民早已是粮食生产者,并发展出粮食生产的许多伴随物(稠密的人口、对疾病的抵抗力、更先进的技术,等等)。结果,虽然南岛人的扩张消灭了原先的印度尼西亚人,但在新几内亚地区却未能取得多大进展,就像它在热带东南亚与说南亚语和傣-加岱语的粮食生产者的对垒中也未能取得进展一样。

We have now traced the Austronesian expansion through Indonesia and up to the shores of New Guinea and tropical Southeast Asia. In Chapter 19 we shall trace it across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar, while in Chapter 15 we saw that ecological difficulties kept Austronesians from establishing themselves in northern and western Australia. The expansion's remaining thrust began when the Lapita potters sailed far eastward into the Pacific beyond the Solomons, into an island realm that no other humans had reached previously. Around 1200 B.C. Lapita potsherds, the familiar triumvirate of pigs and chickens and dogs, and the usual other archaeological hallmarks of Austronesians appeared on the Pacific archipelagoes of Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga, over a thousand miles east of the Solomons. Early in the Christian era, most of those same hallmarks (with the notable exception of pottery) appeared on the islands of eastern Polynesia, including the Societies and Marquesas. Further long overwater canoe voyages brought settlers north to Hawaii, east to Pitcairn and Easter Islands, and southwest to New Zealand. The native inhabitants of most of those islands today are the Polynesians, who thus are the direct descendants of the Lapita potters. They speak Austronesian languages closely related to those of the New Guinea region, and their main crops are the Austronesian package that included taro, yams, bananas, coconuts, and breadfruit.

至此,我们已经考查了南岛人通过印度尼西亚直到新几内亚海岸和热带东南亚的扩张。在第十九章我们还将考查一下他们渡过印度洋向马达加斯加扩张的情形,而在第十五章我们已经看到不利的生态环境使南岛人未能在澳大利亚的北部和西部扎下根来。这种扩张重振余势之日,就是拉皮塔陶工扬帆远航之时:他们进入了所罗门群岛以东的太平洋海域,来到了一个以前没有人到过的岛屿世界。公元前1200年左右的拉皮塔陶器碎片、人们熟知的三位一体的猪鸡狗,以及其他一些常见的关于南岛人的考古标志,出现在所罗门群岛以东一千多英里处的斐济、萨摩亚和汤加这些太平洋群岛上。基督纪元的早期,大多数这样的考古标志(引人注目的例外是陶器)出现在波利尼西亚群岛东部的那些岛屿上,包括社会群岛和马克萨斯群岛。更远的独木舟长途水上航行把一些移民往北带到了夏威夷,往东带到了皮特凯恩岛和复活节岛,往西南带到了新西兰。今天在这些岛屿中,大部分岛屿上的土著都是波利尼西亚人,他们因而都是拉皮塔陶工的直系后裔。他们说的南岛语和新几内亚地区的语言有着近亲关系,他们的主要作物是南岛人的全套作物,包括芋艿、薯蓣、香蕉、椰子和面包果。

With the occupation of the Chatham Islands off New Zealand around A.D. 1400, barely a century before European “explorers” entered the Pacific, the task of exploring the Pacific was finally completed by Asians. Their tradition of exploration, lasting tens of thousands of years, had begun when Wiwor's ancestors spread through Indonesia to New Guinea and Australia. It ended only when it had run out of targets and almost every habitable Pacific island had been occupied.

公元1400年左右,也就是在欧洲“探险者”进入太平洋之前仅仅一个世纪,亚洲人占领了新几内亚海岸外的查特姆群岛,从而最后完成了对太平洋的探险任务。他们的持续了几万年之久的探险传统,是在维沃尔的祖先通过印度尼西亚向新几内亚和澳大利亚扩张的时候开始的,而只是在目标已尽、几乎每一座适于住人的太平洋岛屿都已被占领的时候,它才宣告结束。

TO ANYONE INTERESTED in world history, human societies of East Asia and the Pacific are instructive, because they provide so many examples of how environment molds history. Depending on their geographic homeland, East Asian and Pacific peoples differed in their access to domesticable wild plant and animal species and in their connectedness to other peoples. Again and again, people with access to the prerequisites for food production, and with a location favoring diffusion of technology from elsewhere, replaced peoples lacking these advantages. Again and again, when a single wave of colonists spread out over diverse environments, their descendants developed in separate ways, depending on those environmental differences.

对于任何一个对世界史感兴趣的人来说,东亚和太平洋人类社会是颇有教益的,因为它们提供了如此众多的关于环境塑造历史的例子。东亚和太平洋族群凭借他们地理上的家园,无论在利用可驯化的动植物方面,或是在与其他族群的联系方面,都显得与众不同。一次又一次地,是具有发展粮食生产的先决条件并处在有利于传播来自别处的技术的地理位置上的族群,取代了缺乏这些优势的族群。一次又一次地,当一次移民浪潮在不同的环境中展开时,环境的不同决定了移民们的后代以各自的不同方式发展。

For instance, we have seen that South Chinese developed indigenous food production and technology, received writing and still more technology and political structures from North China, and went on to colonize tropical Southeast Asia and Taiwan, largely replacing the former inhabitants of those areas. Within Southeast Asia, among the descendants or relatives of those food-producing South Chinese colonists, the Yumbri in the mountain rain forests of northeastern Thailand and Laos reverted to living as hunter-gatherers, while the Yumbri's close relatives the Vietnamese (speaking a language in the same sub-subfamily of Austroasiatic as the Yumbri language) remained food producers in the rich Red Delta and established a vast metal-based empire. Similarly, among Austronesian emigrant farmers from Taiwan and Indonesia, the Punan in the rain forests of Borneo were forced to turn back to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, while their relatives living on Java's rich volcanic soils remained food producers, founded a kingdom under the influence of India, adopted writing, and built the great Buddhist monument at Borobudur. The Austronesians who went on to colonize Polynesia became isolated from East Asian metallurgy and writing and hence remained without writing or metal. As we saw in Chapter 2, though, Polynesian political and social organization and economies underwent great diversification in different environments. Within a millennium, East Polynesian colonists had reverted to hunting-gathering on the Chathams while building a protostate with intensive food production on Hawaii.

例如,我们已经看到,中国的华南人发展了本地的粮食生产和技术,接受了华北的文字、更多的技术和政治组织,又进而向热带东南亚和台湾移民,大规模地取代了这些地区的原有居民。在东南亚,在那些从事粮食生产的华南移民的后代或亲戚中,在泰国东北部和老挝山区雨林中的永布里人重新回到狩猎采集生活,而永布里人的近亲越南人(所说的语言和永布里语言同属南亚语的一个语支)始终是肥沃的红河三角洲的粮食生产者,并建立了一个广大的以金属为基础的帝国。同样,在说南岛语的来自台湾和印度尼西亚的农民移民中,婆罗洲雨林中的普南人被迫回到了狩猎采集的生活方式,而他们的生活在肥沃的爪哇火山土上的亲戚们仍然是粮食生产者,在印度的影响下建立了一个王国,采用文字,并在婆罗浮屠建有巨大的佛教纪念性建筑物。这些进而向波利尼西亚移民的南岛人同东亚的冶金术和文字隔绝了,因此始终没有文字,也没有金属。然而,我们在第二章里看到,波利尼西亚的政治和社会组织以及经济结构在不同的环境中经历了巨大的分化。在一千年内,波利尼西亚东部的移民在查特姆群岛回复到狩猎采集生活,而在夏威夷则建立了一个从事集约型粮食生产的原始国家。

When Europeans at last arrived, their technological and other advantages enabled them to establish temporary colonial domination over most of tropical Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands. However, indigenous germs and food producers prevented Europeans from settling most of this region in significant numbers. Within this area, only New Zealand, New Caledonia, and Hawaii—the largest and most remote islands, lying farthest from the equator and hence in the most nearly temperate (Europelike) climates—now support large European populations. Thus, unlike Australia and the Americas, East Asia and most Pacific islands remain occupied by East Asian and Pacific peoples.

当欧洲人终于来到时,他们的技术优势和其他优势使他们能够对热带东南亚的大部分地区和各个太平洋岛屿建立短暂的殖民统治。然而,当地的病菌和粮食生产者妨碍了欧洲人大批地在这个地区的大多数地方定居。在这一地区内,只有新西兰、新喀里多尼亚和夏威夷——这几个面积最大、距离赤道最远、最偏僻的、因而处于几乎最温和的(像欧洲一样的)气候之中的岛屿——现在生活着大量的欧洲人。因此,与澳大利亚和美洲不同,东亚和大多数太平洋岛屿仍然为东亚民族和太平洋民族所占有。

注释:

1. 蜡防印花法:一种起源于爪哇的在棉布上印花的方法。——译者

2. 按:台湾高山族语言属南岛语系。——译者