46

Women became even more important to Mao after one of them discovered the secret bugging devices. It happened not long after Chinese New Year, in February 1961, when we were en route to Guangzhou on Mao's special train.

Wang Dongxing seemed to know from the beginning that the trip would bring trouble. More women than usual were accompanying Mao. “When you put two women together, they are noisier than a gong,” Wang said to me just after we had set out.

In addition to the female train attendants, the young confidential clerk who was so open about her liaison with Mao was there, and so was the woman with whom Mao had quarreled because she wanted to get married. I was startled to see a teacher I knew well there, too, and even more shocked to learn of her longtime liaison with Mao. The kind and honest young teacher had met Mao at one of his dances, and the two had struck up a relationship then. She had never been further from Beijing than the Fragrant Hills, and Mao had invited her along to show her the world.

The wife of a high-ranking military official, a dark-skinned, depressed-looking woman of about forty, was also there. She was said to have known Mao in Yanan. He had sent her off to the Soviet Union when their romance faltered and later arranged for her to marry the military official. Jiang Qing had long known about the romance and vengefully wanted the woman's husband demoted. But the man was a close associate of Peng Dehuai's, and so long as Peng remained minister of defense, the military official was protected. But when Peng was purged in 1959, that protection was gone, and Jiang Qing had begun pressuring Lin Biao to take action against the official. The wife, obviously anxious and unhappy, had come to persuade Mao to intercede on her husband's behalf.

Mao called her into his compartment several times while we were traveling, and on the first night after our arrival in Hangzhou I could not help but notice that she spent several hours there. Just after she left his room, though, she disappeared. One of the other women became worried and asked me to help find her. The woman was not found until early the next morning. She and Mao had quarreled, and she had spent the night huddled on a rock by the lake, crying. Mao sent her back to Beijing that day.

After a few days in Hangzhou, we headed west by train toward Wuhan, stopping briefly so Mao could meet with Zhang Pinghua, Hunan's first party secretary.

The meeting took place on the train, and Mao was late.

He was lingering in his compartment with the female teacher while Zhang and his deputy, Wang Yanchun, waited in the adjacent reception car. Wang was so rooted in his peasant ways that he squatted rather than sit on the sofa. When Mao finally emerged, I joined the teacher and several of his other female companions for a stroll outside the train. Liu, the young technician responsible for secretly recording Mao's conversations, joined us in our meanderings.

“I heard you talking today,” the young technician suddenly said to the teacher, interrupting our idle chatter.

“What do you mean you heard me talking?” she responded. “Talking about what?”

“When the Chairman was getting ready to meet Zhang Pinghua. You told him to hurry up and put on his clothes.”

The young woman blanched. “What else did you hear?” she asked quietly.

“I heard everything,” Liu answered, teasing.

The woman was stunned. She turned and bolted for the train as the rest of us followed quickly behind. The other women were also distressed. If Liu had heard one conversation with Mao, surely he had heard others as well.

Mao's meetings were concluding as we returned to the train, and the teacher went immediately to his compartment, demanding to speak with him. She reported the entire conversation with Liu.

Mao was livid. He had never suspected the bugging. The revelation came as a shock. He called Wang Dongxing into his compartment, where the two stayed behind closed doors in intense conversation for an hour. Wang, so recently returned from exile, claimed not to know about the bugging devices, either. When he emerged from the meeting, he ordered the train to proceed immediately, at top speed, to Wuhan.

As the train sped north, Wang called the technician Liu and confidential secretary Luo to meet with him, informing them that the Chairman wanted to know who had ordered the bugging. Wang claimed that since this was the first trip he had taken with the Chairman since his return, he simply took all the staff members who ordinarily accompanied the Chairman, including the recording technician. Wang began interrogating the young men and told Liu that Mao had ordered his arrest.

But Wang did not arrest the technician. “You have no place to run,” he told him. But he demanded to know who had ordered the bugging.

Confidential secretary Luo pleaded ignorance. He said the bugging had started when Ye Zilong was in charge. Ye was the man to consult. But Ye was away doing labor reform.

Liu also claimed not to know. He was just doing his job, he said, acting under orders from “the leadership.”

“And did the leadership order you to record the Chairman's private conversations, too?” Wang Dongxing demanded, glaring at the young technician. “Don't you have anything better to do? Why were you looking for trouble? Why didn't you tell Chairman you wanted to record his talks? You recorded all sorts of things you never should have. What am I supposed to tell Chairman?”

Liu was speechless.

By the time our train reached Wuhan and we had settled into the Plum Garden guesthouse, it was four o'clock in the morning. Wang Dongxing and Liu roused a local electrician and went immediately to remove all the bugging equipment from the train. I went to bed.

When I woke that afternoon, the bugging equipment—recording machines and tapes, speakers and wires—had been put on display in the conference room, and the staff was gathered around examining the paraphernalia. The Plum Garden guesthouse had also been bugged, and that equipment was on display, too. Mao ordered photographs taken as evidence, with Wang Dongxing, Kang Yimin, Luo, and Liu standing behind the table.

Kang Yimin, the deputy director of the Office of Confidential Secretaries who had worked just under Ye Zilong, had come from the General Office in Zhongnanhai to discuss the matter with Wang Dongxing. Kang was a simple, honest, but uneducated man, and he and Wang quickly came to blows. Kang knew that the real decision to record the Chairman's conversations had come from higher up than Ye Zilong. Bugging the Chairman was far too serious a matter to be decided by Ye. Why they—or I—ever thought it could be gotten away with, I will never understand.

Confronted with Mao's discovery and not wanting to bring unknown higher levels into the dispute, Kang wanted Wang Dongxing to find some convincing way to explain the whole thing away. But Wang was determined to find out where the order had originated. Mao wanted an investigation, and Wang Dongxing was determined to conduct it.

In the end, though, the two men compromised. Wang Dongxing agreed to tell Mao that the bugging had been ordered to provide material for a party history.

Mao was infuriated. “So they're already compiling a black report against me, like Khrushchev?” he bellowed. A “party history” based on bugging his private conversations could only be used against him, and nothing bothered him more than the possibility of the type of attack Khrushchev had launched against Stalin. The attack against Stalin had also been full of damaging personal detail, and Mao did not want the details of his own personal life recorded on tape.

But it was not these revelations he most feared. His private life was an open secret among the party elite. His greatest fear was the potential threat to his power. Mao's frequent travel to other parts of China, where he met alone with local leaders, was part of his political strategy, a tactic designed to leap over the cumbersome bureaucratic machinery of the party and state and to maintain direct contact with local-level leaders. He did not want the central authority to know what he said to the provincial and local-level leaders. His role as the source of all policy would be diminished were representatives to carry his words back to Beijing, where central leaders could devise policy based on his conversations outside the capital. Mao wanted the central authorities to be more directly dependent on and loyal to him. If they knew what he said when traveling, they could pay lip service to their loyalty without having to be dependent. That was what he was trying to avoid.

He ordered Wang Dongxing to burn the tapes immediately. “Don't leave a single one,” he commanded. “I don't want them providing material for any black report.” Faced with Mao's fury, Liu confessed that other places, including the Wangzhuang guesthouse in Hangzhou that we had just left, were also bugged. Mao ordered Wang to dispatch a team to remove that equipment and destroy those tapes, too.

Several people lost their jobs as a result of the incident. Ye Zilong's lieutenant Kang Yimin and Mao's confidential secretary Luo were both fired. Kang went to work in the People's Bank. Luo was transferred to the Second Ministry of Machine Building and was replaced by Xu Yefu, the confidential secretary who had earlier lost his job when he talked openly about Li Yinqiao's accusation that Jiang Qing was running away to Hangzhou to avoid being criticized. Liu, the witless technician whose teasing of Mao's girlfriend had precipitated the discovery, was sent to Shaanxi for labor reform.

Mao never believed that the underlings who lost their jobs in 1961 were the real culprits. “They don't understand what this is all about,” he said. “They don't know anything.”

Mao, like Kang Yimin, believed that the orders to listen in on his conversations could have come only from leaders at the highest level. The Ministry of Public Security would have to be involved, too. Mao was convinced that they had been spying on him as part of a plot. His growing belief that there was a conspiracy against him within the highest ranks of the party dates from here. The differences between Mao and the other party leaders were still hidden, but the rift that would explode with the Cultural Revolution was quietly widening. Mao was biding his time.

Mao was unnerved by the bugging incident. Ordinarily suspicious, he had still never imagined that secret recording devices had been picking up his every word, that tapes of his conversations were being sent back to the central secretariat in Beijing. Nearly as shocking to Mao was the behavior of his personal staff. He assumed that his inner circle, in whom he had placed his trust, who had served him most loyally and longest, had been part of the plot. He knew we were aware that his conversations were being recorded and sent to the central secretariat. But we had kept it a secret. Mao became more wary of his staff following this episode. His faith in our loyalty began to decline. He came to trust women far more than men, dismissing his male attendants and surrounding himself with women. His young women came to serve as his personal attendants and trusted confidantes.

Mao's increasing wariness of me dates to this episode, too. When he asked, “Any news?” as he did every time we met, he wanted me to tell him everything I knew. Failure to disclose everything could be taken as evidence of a plot. His suspiciousness began to take deeper hold, and Mao never fully trusted me again.

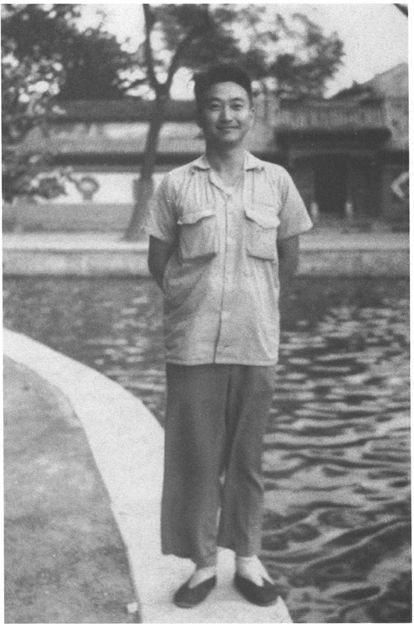

Summer of 1954, in Zhongnanhai. Dr. Li Zhisui standing outside Mao Zedong's walled compound, in a photograph taken by Wang Dongxing. ↓

Summer of 1956. Dr. Li swimming in the Yangtze River, near Wuhan. (Mao Zedong is ahead of Dr. Li, out of the picture.) ↓

November 1957, at the Kremlin, Moscow. Mao Zedong taking leave of Nikita Khrushchev, Anastas Mikoyan, and Nikolai Bulganin. From left to right: Dr. Li, Mao, and bodyguard Li Yinqiao. ↓

November 1957, at the Kremlin, Moscow. From the left: the second person is head nurse Wu Xujun, the fourth is Mao Zedong, the fifth is Yan Mingfu (Russian interpreter), and the seventh is Dr. Li. ↓

Early summer 1961, at Wangzhuang guesthouse, Hangzhou, after Mao Zedong met with a foreign guest. In front, from the left: Mao, Wang Dongxing, and Dr. Li. Behind Mao is Zhejiang security chief Wang Fang. ↓

Summer of 1961, at Lushan. From left to right in the second row, starting with the second person: Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong, unidentified, Dr. Li, and Wang Dongxing. Seventh and eighth in the third row are political secretary Lin Ke and security officer Shen Tong. The others are nurses, bodyguards, and local chiefs of security. ↓

Summer of 1961. Dr. Li, photographed by Jiang Qing. ↓

Summer of 1961, at the new Lushan guesthouse, where Mao Zedong encountered his third wife, He Zizhen. From left to right: provincial security officer Lu, Wang Dongxing, confidential secretary Xu Yefu, confidential clerk Li Yuanhui, Dr. Li, head nurse Wu Xujun, Mao Zedong, nurse Zhou, and two bodyguards. ↓

December 26, 1964, Mao Zedong's seventy-first birthday. In front of Room 118, in the Great Hall of the People, from left to right: bodyguard Xiao Zhang, security guard Wang Yuqing, Central Garrison Corps commander Zhang Yaoci, Mao, head nurse Wu Xujun, Dr. Li, political secretary Lin Ke, and bodyguard Zhou Fuming. ↓

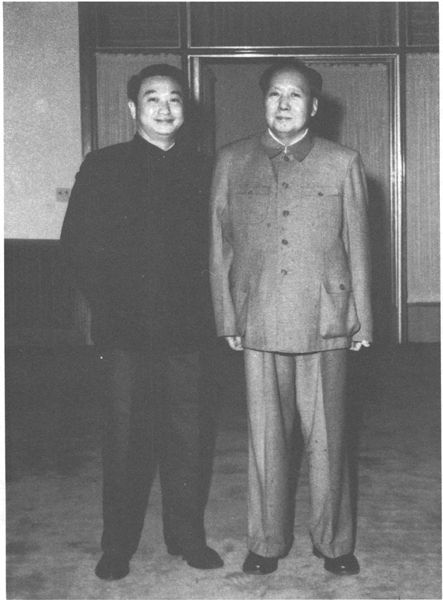

December 26, 1963, Mao Zedong's seventieth birthday. Dr. Li and Mao pose in front of Room 118, in the Great Hall of the People. ↓

Jinggangshan, May 1965. Dr. Li, Mao Zedong, and head nurse Wu Xujun in front of the guesthouse. ↓

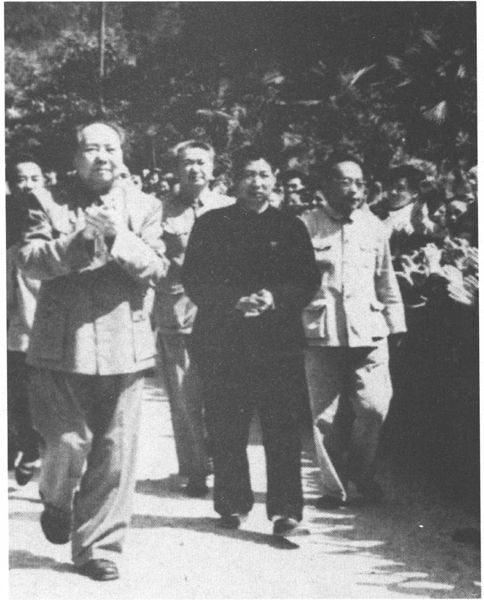

Mao Zedong being greeted by local people, Jinggangshan, May 1965. To Mao's left are Dr. Li and the local governor. ↓

Meiyuan (Plum Garden) guesthouse, Wuhan, July 3, 1966. Dr. Li and Mao Zedong, shortly before Dr. Li's return to Beijing to investigate the Cultural Revolution. ↓

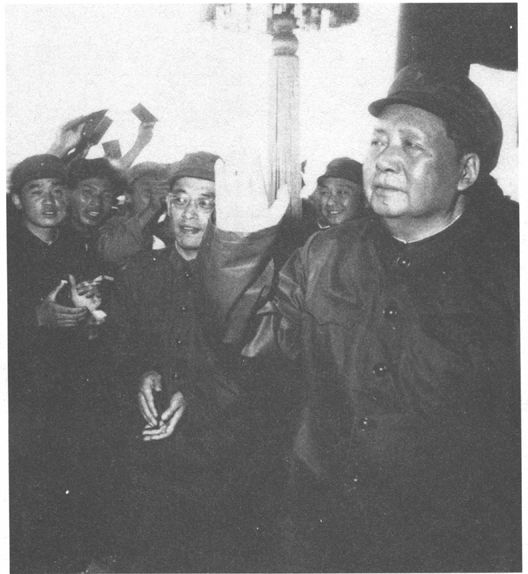

Atop Tiananmen, August 1966. Mao Zedong greets the Red Guards. Dr. Li is just behind Mao. ↓

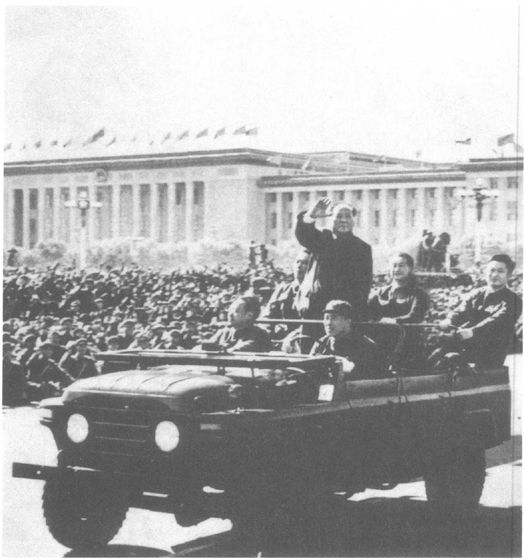

November 1966. Mao Zedong reviews the Red Guards from an open jeep. In the front seat: Wang Dongxing and driver. In the backseat: minister of public security Xie Fuzhi, Mao, Dr. Li, and bodyguard Zhou Fuming. ↓

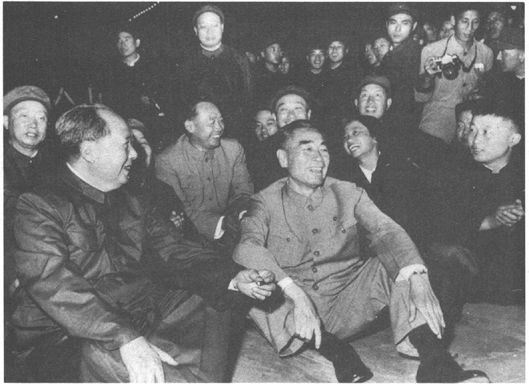

Tiananmen Square, October 1, 1966, on the seventeenth anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic. Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai left the balcony atop Tiananmen to join the Red Guards in the square. In front, Mao and Zhou. In the second row, Wang Dongxing is the third person from the left, Dr. Li is just behind Zhou, and head nurse Wu Xujun is beside Dr. Li. Standing directly behind Wang Dongxing are bodyguard Sun Yong and Central Garrison Corps commander Zhang Yaoci. The others are guards. ↓

December 26, 1967, Mao Zedong's seventy-fourth birthday. Mao poses with members of the First Company of the Central Garrison Corps near the indoor swimming pool. Wang Dongxing is to the left of Mao, Dr. Li is to the right, head nurse Wu Xujun stands in front of Dr. Li, and Central Garrison Corps commander Zhang Yaoci is at the extreme right. ↓

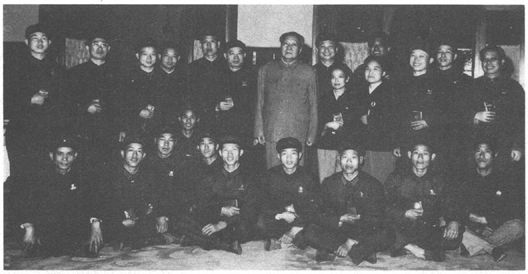

Fall of 1969, in front of Mao Zedong's special train, at Tianjin. Clerk Sun Yulan (with glasses) and nurse Ma (with pigtail) are in the middle of the front row. Second row, from right to left: Dr. Li, Central Garrison Corps commander Zhang Yaoci, head nurse Wu Xujun, and Wang Dongxing. Mao is eighth from the left. The others are attendants, nurses, chefs, and secretaries. ↓

Early 1972, Chinese Spring Festival, at the duty room of the indoor swimming pool. From left to right: Dr. Hu Xudong, Central Garrison Corps commander Zhang Yaoci, Premier Zhou Enlai, Dr. Li, and Dr. Wu Jie. ↓

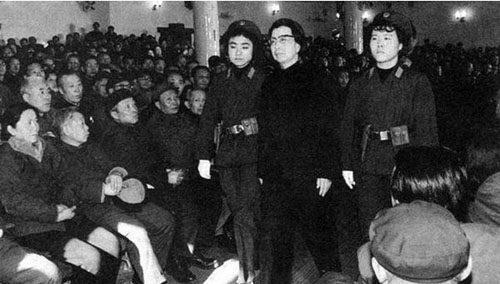

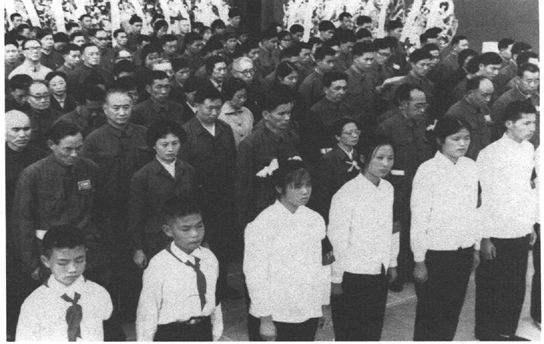

September 1976, during the ceremony commemorating Mao's death. Dr. Li is the second person from the left in the third row. The others are doctors, nurses, and security officers. ↓

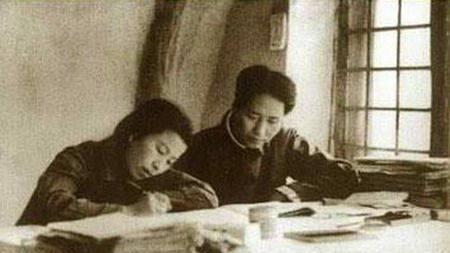

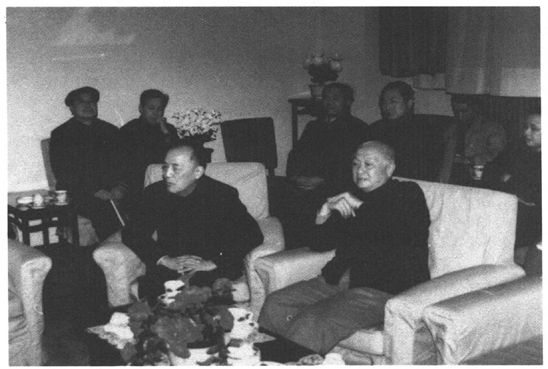

December 26, 1977, at a workshop concerning the preservation of Mao Zedong's remains. Dr. Li is seated in the foreground, on the right. Beside him is Huang Shuze. ↓

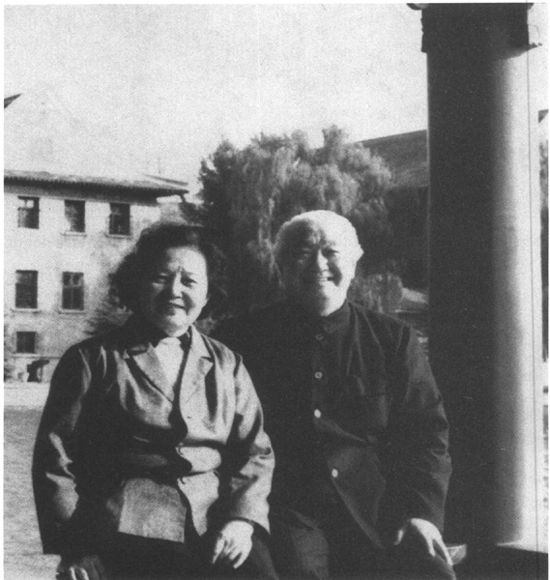

Early summer 1984, at the South Lake dock in Zhongnanhai. Dr. Li and his wife, Lillian. Dr. Li's apartment was on the third floor of the building, overlooking the lake. ↓